24-25. retroviridae I & II

1/34

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

35 Terms

where did human immunodeficiency viruses come from?

zoonosis → multiple simian immunodeficiency viruses that jumped into human hosts

what type of genome do retroviruses have?

RNA

are retroviruses naked or enveloped?

enveloped

envelope proteins often heavily glycosylated → masking from antibodies

what types of cells do retroviruses frequently target?

lymphocytes and/or macrophages → systemic spread, proliferation of infected cells

unique/notable properties of retroviruses

reverse transcriptase: RNA → DNA

error-prone → high mutation rate; rapid evolution

diploid particles (2 RNA copies) → facilitates within-host recombination

integration of DNA provirus into host cell’s genome

enables long-lived, persistent, latent infections

cancer: insertional mutagenesis; disruption of normal gene expression

how can oncogenic retroviruses cause cancer?

through recombination, retroviruses can acquire cellular oncogenes → these mutate through viral passage, becoming viral oncogenes (v-onc)

viral oncogene-encoding viruses transduce the oncogene, rapidly causing cancer

require “helper viruses”; no longer able to recompilation on their own

viruses can insert next to a cellular oncogene and upregulate its expression, causing cancer more slowly

(complex retroviruses may have other oncogenic mechanisms)

feline lymphoma & FeLV infection

lymphoma usually manifests as multicentric or thymic T cell tumors, frequently in cats < 3 y/o

multicentric, mediastinal: associated with FeLV; decreasing incidence

GI lymphomas: B cell tumors; more common currently; generally in older cats

tumors develop slowly after FeLV infection → upregulation of cellular oncogene c-myc

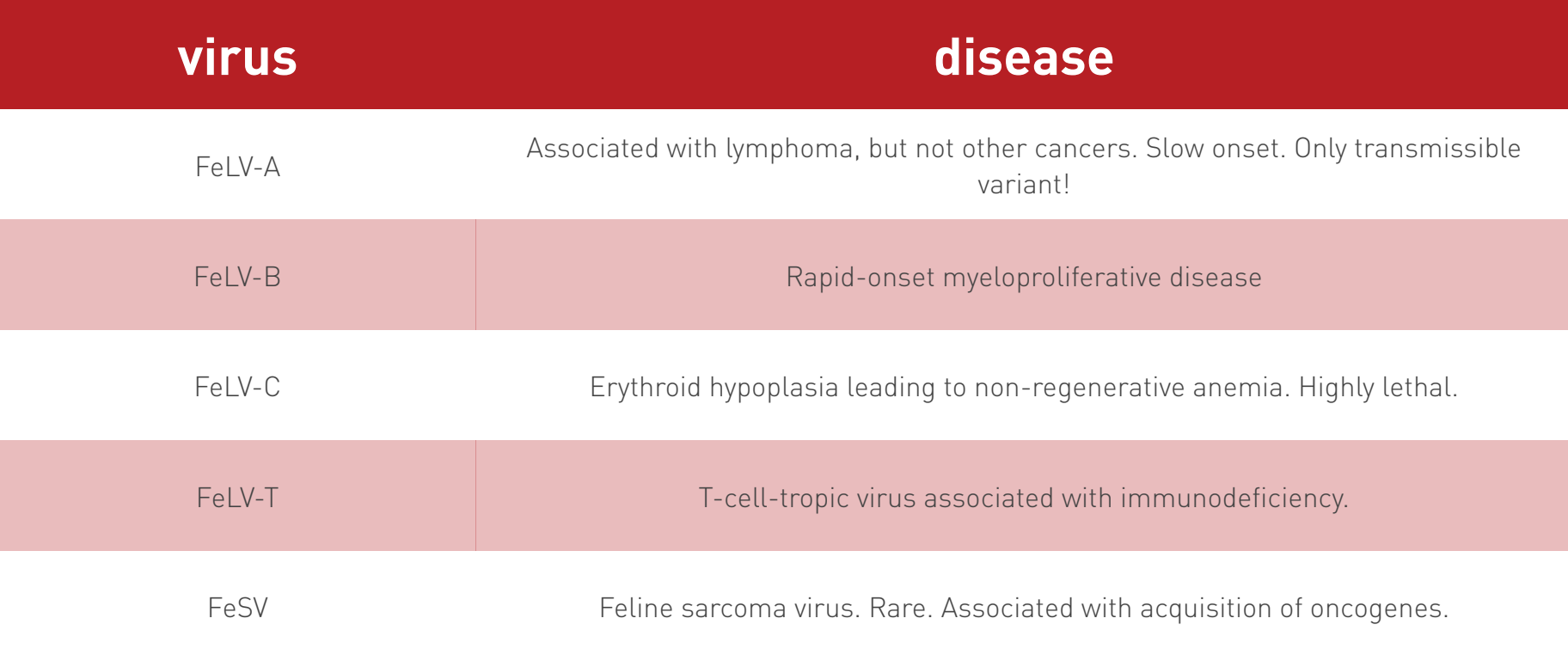

FeLV variants

only FeLV-A is replication-competent and transmissible among animals

other forms arise in infected cats through mutation — recombination between FeLV & endogenous retroviruses or cellular proto-oncogenes

non-A viruses occur only as co-infections, with FeLV-A as their helper virus

these variants are not replication-competent

multiple variants have been described in association with specific disease complexes

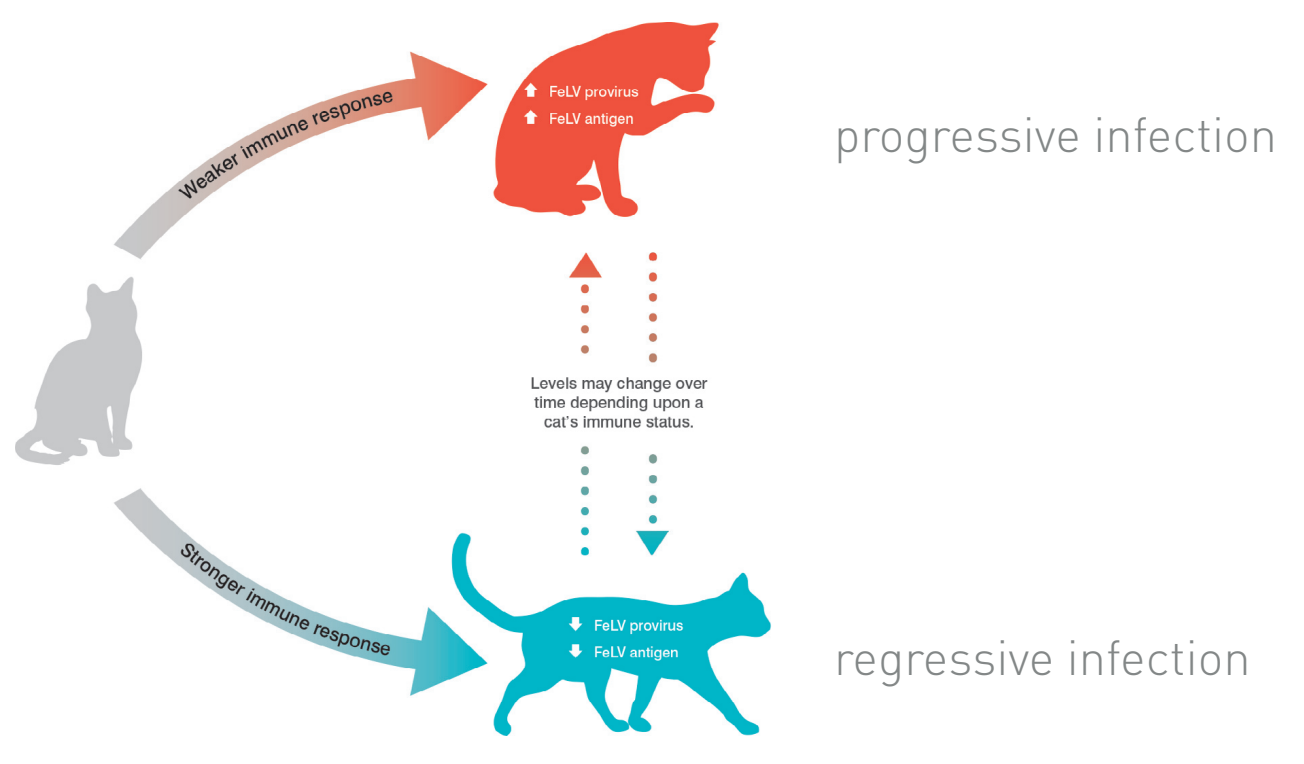

FeLV progressive vs. regressive infection

progressive infection (high-positive)

weaker immune response → higher levels of FeLV provirus & antigen

persistent high viremia & eventual disease

regressive infection (low-positive)

stronger immune response → lower levels of FeLV provirus & antigen

(apparent) clearance of antigenemia; potential for longer survival

primary & secondary FeLV infection

primary: initial infection; characterized by infection of lymphoid tissue

secondary: infection of bone marrow sets up persistent viremia and progressive infection

abortive FeLV infection

no viral antigen or DNA detected, but antibodies present

FeLV clinical signs

nonspecific symptoms

fever of unknown origin

lymphadenopathy

immunosuppression

wasting

abortion

anemia

cattery history

FeLV diagnosis

serology most common → ELISA and IFA tests for FeLV antigen

level 1: ELISA tests detect cell-free virus

screening test; serum

level 2: PCR for proviral DNA and RT-PCR for genomic RNA; or IFA (hardy test) to detect cell-associated virus

used to confirm positive ELISA

PCR commercially available

whole blood may be best sample type

FeLV transmission

secreted in saliva, blood, urine, feces

primarily horizontal transmission → prolonged friendly contact

dose required for oronasal transmission is likely high

can also occur in utero or perinatally

FeLV control

test and remove; isolate infected animals

test prior to vaccination, breeding, or co-housing; test all sick cats

do not decide to euthanize on the basis of (+) ELISA alone

vaccinate

may prevent clinical disease but not infection

highly recommended for all kittens

2 dose initial series, followed by booster and assessment for exposure risk

what neoplasm is associated with bovine leukosis virus? what organs does it typically affect?

lymphosarcomas

organs affected:

heart (right atrium)

uterus

nodules in central and peripheral lymph nodes

abomasum

other sites, causing additional tissue-specific signs

BLV & persistent lymphocytosis

PL develops after a latent period lasting from months to several years

detectable in blood samples, but otherwise not clinically apparent

distinct from leukemia → normal lymphocytes; could become leukemia

increases animal’s risk of developing leukemia by 2x

BLV diagnosis

routinely diagnosed by presence of antiviral antibody (after 6 months of age)

PCR tests for provirus also available

BLV pathogenesis

mechanism not completely defined, but involves viral Tax protein, a transcriptional transactivator

implicated in oncogenesis

inhibition of apoptosis?

may promote viral “sneakiness” by downregulating viral gene expression

BLV clinical signs

tumors typically take several years to develop

once animals develop symptomatic disease, frequently suffer weight loss and milk production is greatly reduced

lymphosarcoma is rapidly progressive → wasting, death within 4 months of diagnosis

BLV transmission

iatrogenic transmission most common (exposure to infected cells)

BLV is strongly cell-associated, so not easily transmitted among animals

vertical transmission ineffecient

horizontal transmission among adult cattle

calves can become infected after birth (exposure to exudate & placenta from cows; calving instruments)

biting insects? evidence inconclusive

proviral load is associated with transmission risk

BLV control

no vaccine available in US

test and slaughter, or test and segregate

PCR tests make it possible to identify and remove “super-shedders”

avoid procedures that can transmit infected lymphocytes (ex. do not reuse equipment; clean and disinfect between animals)

manage biting insects

FIV serotypes

at least 5 (A-E)

A & B predominate in US

animals can be superinfected with multiple subtypes

FIV transmission

primarily secreted in saliva

horizontal transmission → fighting and biting

prevalence higher among (intact) males than females

can also be transmitted in utero or through milk, particularly by acutely infected queens

(grooming, sexual contact NOT thought to be major modes of transmission)

FIV pathogenesis

replication kinetics similar to HIV/SIV → high acute viremia followed by long asymptomatic stage

decline in CD4+ T cells eventually leads to immunodeficiency

tempo & severity of disease may be dependent on age of animal and route of infection

FIV clinical signs

acute infection

nonspecific, “flu-like symptoms”: fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy

transient; not always apparent

may have long latent stage

chronic gingivitis, stomatitis

chronic upper respiratory disease, enteritis

opportunistic infections, including FeLV

FIV diagnosis

tumors are a common reason for FIV-infected cats to be brought in

presenting signs may also be similar to FeLV

IFA or ELISA → test for antibody against FIV

kittens may test false + for first ~12 wks due to maternal Ab

generally recommended to wait (or retest) at least 6 months after birth

FIV control

best control is prevention → avoid contact with free-roaming cats

vaccine no longer used in US

vaccinated animals seroconvert, confounding diagnostic tests

FIV strain variability is a major obstacle to effective vaccine development

equine infectious anemia virus (swamp fever) transmission

largely mechanical transmission by blood-sucking insects (tabanid & stable flies)

other modes, including iatrogenic possible

EIAV pathology

causes lifelong, persistent infection

acute infection may be clinically inapparent, though some animals have rapidly progressive disease

disease characterized by multiple interchanging syndromes; recurrent bouts of fever and illness

death occurs after many years of progressive, debilitating illness

EIAV clinical signs

7-21d incubation

acute onset of fever, mucosal hemorrhage, hemolytic anemia, fatigue, weakness, jaundice

high case fatality when acute signs apparent (up to 80%, particularly in foals?)

subacute: recurrent fever, anemia

recovered: no clinical signs, suitable for work

chronic: failure to thrive, fatigue, cachexia

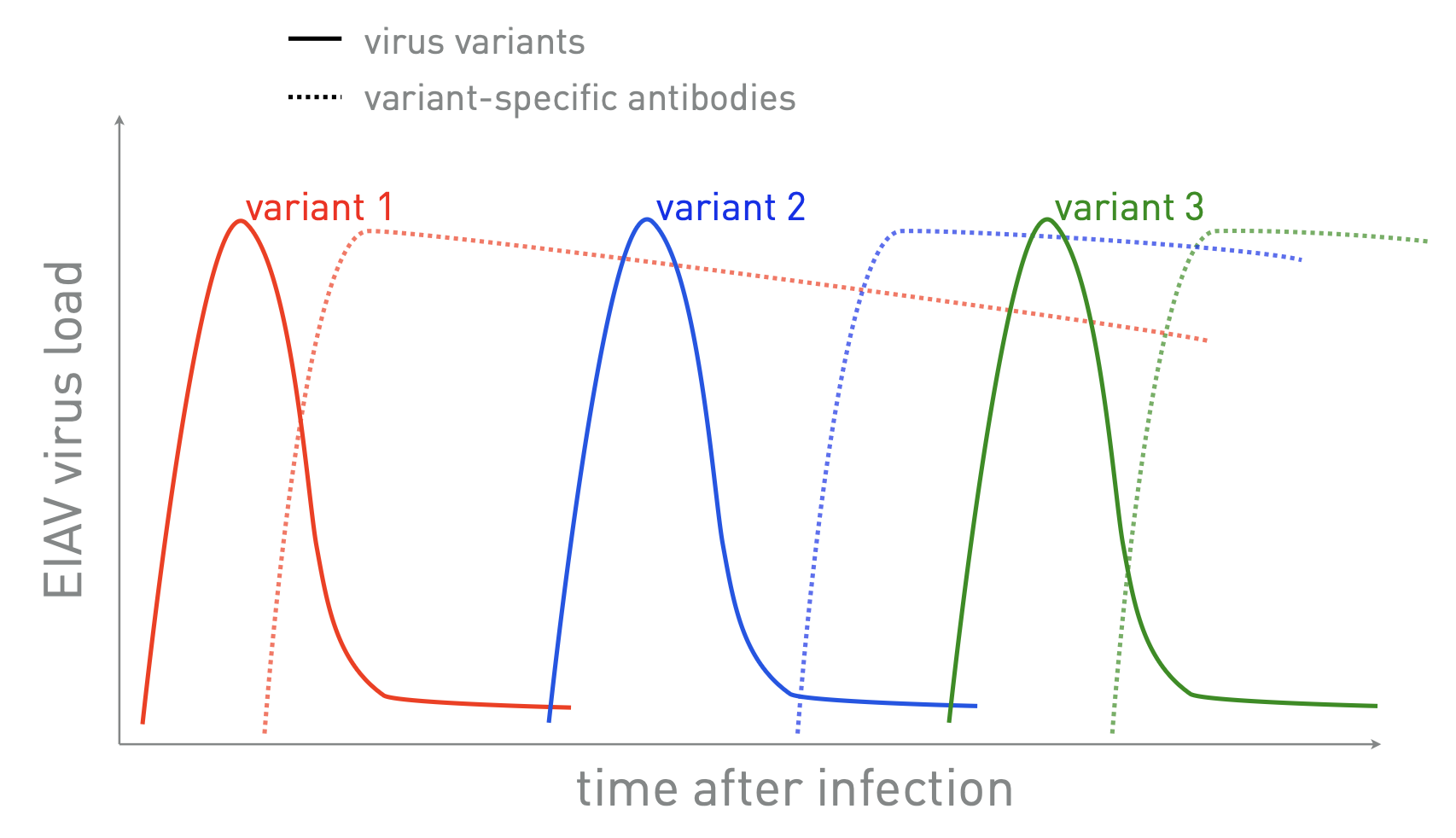

why does EIAV cause recurring bouts of illness?

within-host evolution → continually spawns novel antigenic variants that “escape” immune response

EIAV diagnosis

Coggins test: agar gel immunodiffusion (AGID) detects anti-EIAV antibody

being replaced with ELISA tests: faster, can perform in field

Western blot (confirmatory)

PCR

** negative Coggins or ELISA required to transport animals across state lines

in what region(s) of the US is EIAV prevalent?

southeastern US, texas, (and mississippi valley?)

EIAV control

spread controlled by euthanasia/isolation of infected animals & insect control

due to antigenic diversity, vaccines are not effective