CYC W2 - SLIDE SHOW - HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES AND REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

1/30

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

31 Terms

beginnings of professionalized caregiving

evvovled in western socicietes

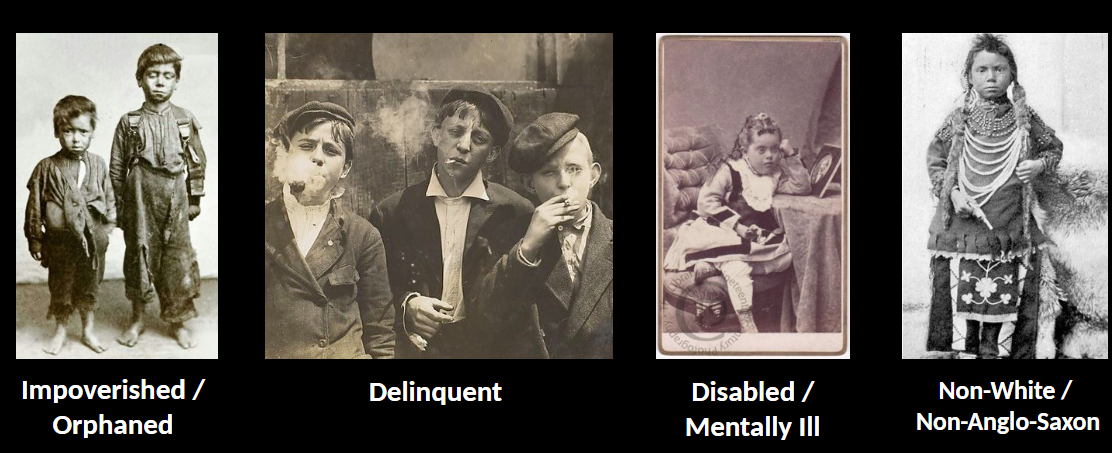

institutional response to marginalized children

aim

socialization, assimilation, rehabilitation

evolution of CYC profession

infleunced by:

industrialization, capitalism, classism, and colonialism, white supremacy

christianity and the church

individualism

equality and democracy

rational and scientific though

colonialism

system that occupires and usurps labor/land/resources from one group of people for the benefit of another

3 PARTS TO COLONIALISM

Canada is still a settler colonial state, the system continues to shape modern institutions, benefit settlers and oppress indigenous peoples

SETTLE COLONIALISM

settler colonialism - acquisition of land through the replacement of indigneous people by settler

Manuel’s 3 pts of colonialism

dispossession

lands are stolen from indigenous people

doctrine of discovery used to assert authority over non christian lands

DEPENDENCE

strip ability of indigneous peoples to care for themselves

cut off access to land

promote welfare/tutelage policies

oppression

unjust or cruel exercise of power or authority

Racism + systemic

racism

ideas or practices that establish, maintain, or perpetuate racial superiority or dominance of one group over another

systemic (institutional) racism

patterns of behaviour , policies, or practice that are part of the structures of an organization, and which create or perpetuate disadvantage for racialized persons

in contrast to interpersonal/individuals and internalized racism

racism - anit indigenous and antiblack

anti-black

prejudice, attitudes, beleiefs, stereotyping and discrimination that is discreted at people of african descent

rooted in unique hisory and expereince of enslavement and its elgacy

antiblack racis entrenched in canadian institutions, policies, practices to the extent that anti-black racism is either functionally normalized or rendered invisible to larger white society

anti indigneous racism

ongoing race-based discrimination, negative stereotyping and injustice expereinced by indigneous peoples withing canada

includes ideas and practices that establish, maintain and perpetuate pwoer imbalances, systemic barriers, inequitable outcomes that stem from the elgacy of colonial policies and practices in canada

professionalzied caregiving - industrial societies

early modern period - 15-17 century- impoverished and orphaned ueropean children - street invovled or sold as apprentices, servants, farmer, labourers,or business helpers

orphanages, run by churches, main social support for orphaned or impoverished children

young educated through apprenticeships

upper class children were privileged bby multigenerational wealth and access to formal education

working class families saw education as means of upward mobility

professionalzied caregivers in western industrial societies

18th century

expansion of colonialism, industrialization, urbanization created new social chalennges, growing cities

marginalized children - adult responsibilities at younger ages

british law- children considered adults at age 7

impoverished euro children laboured in harsh factory, farms, furtrade, domestic services

high 5 children = orphaned, neglected, abused, at risk for delinquency

youth with various challenges - housed together in or orphanges, jails, little attention to their unique needs

emergence of european reformers challenged views dominant views of children, arguing that children are basically good, against, physicla punishment, education

professionalized caregiving - modern western society

19th century

expanded european settlement included large numbers of children who arrived on their own or sent by agencies or criminal court

18th centruy reformers inspired changes in public attitudes toward children (physical punishment less toelrated), leading to child savers, educational reform, fresh air movements, advocated for development of child serving laws and institutions

establishment of YMCA, YWCA and boys and girls clubs - impoverished immigants

first juvenile justice facility in canda

industrial schools - serve neglected and problem children

laws restricitng child labour in ontario

laws for compulsory schooling and public education in ontario, chapioned by egerton ryerson

establishment of first childrens society through leadership JJ kelso- journalist and advocate for children, 1wt superintended of eglected and dependent

professionalzied caregiving POST WW2 ERA(1940-1960

modern professionalzied cyc emerged in residential institutions

large correctional institutions developed to housejuvenile deliquents , large hospitals for children with special needs

des\institionaization movement led to large orphanges were replaced by expansaion of smaller, specialized treatment programs in communities (foster care, group homes, treatment centres, staffed by professionals

shift from religious leadership to public, rural to urban

early writings about milieu therapy

dr alberte trieschamn, dr fritz redl, dr bruno, bettleheim

professionalized caregiving - specialzied intervention era (1960-1970)

New developments in CYC

professionalization in North

America, including Ontario:

– Ontario Association of Child and

Youth Councilors established in

1969

– Formal post-secondary education

program started in 1969

normalization and professionalization era - 1970s - 1990s

Normalization and mainstreaming

philosophies promoted the inclusion

of people with disabilities into

“regular” classrooms

• Post-secondary education became

‘criteria’ for being in the profession

• Educational programs attempt to

define CYC competencies and curricula

quality of care and service era - 1990s to present

Greater emphasis on community engagement,

partnerships, and quality of care in children’s

services

• Continuing advancements in professionalization

– Development of education & training programs

– Certification of practitioners

– Emphasis on evidence-based practice

intergenerational trauma

Historic and contemporary trauma that has compounded over

time and been passed from one generation to the next. The

negative effects can impact individuals, families, communities and

entire populations, resulting in a legacy of physical, psychological,

and economic disparities that persist across generations. (Ontario,

2019)

Also known as transgenerational trauma, generational trauma

(and related to concept of historical trauma)

residential schools 1876-1996

instituted as way toa dvance the colonization fo indigneous peoples through assimilation

“I want to get rid of the Indian

problem...our object is to

continue until there is not a

single Indian in Canada that

has not been absorbed into the

body politic...”

Duncan Campbell Scott

Deputy Superintendent of Department

of Indian Affairs (1913-1932)“Agriculture being the chief interest, and

probably the most suitable employment of the

civilized Indians, I think the great object of

industrial schools should be to fit the pupils for

becoming working farmers and agricultural

labourers, fortified of course by Christian

principles, feelings and habits.”

Egerton Ryerson

Superintendent of Schools for Upper Canada

residential, schools -severe trauma, abuse = intergeneration

over 150,000 children atttended

children were removed from families

faced severe physical , emotional, sexual abuse, banned form cultural practices,

estimated that 6,000-50000 children died

After WW2 state child welfare agencies began mass apprehension of indigneous children during “ Sixties scoop”

20000 indigneous children palced up for adoption and foster care with white middle class families

based on policy shift - allowed governemnts to remove aboriginal children in their “best interests”

truth an reconcilitation day

Commission launched in 2008 to

document the history and impacts of

residential schools

• Over 6,000 testimonials, plus

documentary records

• Report released in 2015 with

recommendations to address:

- Child welfare

- Health

- Education

- Justice

- Language and Culture

segregation

Racial segregation

(formal or informal

separation of people

according to race) was a

common feature in public

spaces, schools (until the

1960s in Ontario), and

orphanages

Resistance

Resistance

Many instances of African Canadian resistance

and empowering youth engagement

British-American Institute (1841-1868)

• Founded by Black Canadian Abolitionist Rev.

Josiah Henson (1789-1883)

• Established at Dawn Settlement in Dresden,

Ontario

• School included:

- Teacher training

- Student training in agriculture, blacksmithing,

trades, domestics

- Sale of goods produced by students

nova scotia homes for coloured children

Established in 1921 as an orphanage for children of

African descent in Nova Scotia, due to segregation and

pervasive racism

• Initially envisioned as industrial school to promote youth

empowerment

• Churches paid important role in sponsoring the

orphanage

• Children experienced abuse, cold, hunger, neglect,

isolation

• A restorative inquiry in 2014 led to public apology, and

acknowledged role of systemic racism in abuses

professional development and reflective practice

Professional development is a lifelong journey that requires

practitioners to actively engage in self-directed learning from

their practical experience

According to Budd (2020), professional development involves a

deepened ability to consciously use Self in relationship

Recently, CYC literature has emphasized the improvement of

praxis, through experiential learning and reflective practice

reflective practice

Reflective Practice is an aspect of Reflective practice provides the

opportunity for practitioners to think back to an experience, evaluate their

actions, contemplate why they did what they did, think about the impact on

practice, and consider how practice can be improved (Budd, 2020)

Schon (2016) proposes two types of reflective practice:

Reflection-in-action

occurs in the moment of interaction, forming mental pictures of what you are doing, identifying

options & choices while interaction is occurring

Reflection-on-action

occurs after the interaction, involves describing what happened, articulating choices, and

rationale for making those choices

reflective journals

According to Budd (2020), objectives of journals are to establish continuity

between experience, reflection, and learning

• Promote self-knowledge, critical thinking, personal growth

• Common approaches to reflective journaling include

– Describing the experience and your emotional reactions

– Describing your actions

– Evaluating the situation

– Establishing further action

Praxis

Praxis is ethical, self-aware, responsive,

accountable action that integrates

knowing, doing, and being (White,

2007)

Social justice praxis (aka politicized or

critical praxis) focuses on issues of

power, oppression, sociopolitical and

historical context of practice (Igbu &

Baccus, 2018; Saraceno, 2012; Skott-

Myhre & Skott-Mhyre, 2011)

residential video

Origins and Establishment of the System

Pre-1831: For over 200 years, religious orders ran mission schools for Indigenous children, which were the precursors to the government's residential school system [00:08].

1831: The Mohawk Institute became a boarding school, making it the first government-funded residential school in Canada [00:16].

1847: A government report recommended separating Indigenous children from their parents to assimilate them into Western culture, influencing federal laws and policies designed to strip Indigenous people of their culture and rights [00:25].

1876: The Indian Act was passed, giving the Canadian government control over Indigenous rights and culture for First Nations (excluding Métis and Inuit) [00:57].

1883: Prime Minister John A. Macdonald authorized the creation of the residential school system, designed to isolate Indigenous children from their families and cut all ties to their cultures. The number of schools quickly climbed to over 40 [01:14].

Operation, Neglect, and Resistance

1907: Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce exposed the government's neglect of Indigenous children's health, including alarmingly high death rates among residential school students [01:39].

1920: The Government of Canada made attendance at residential schools mandatory for First Nations children aged 7 to 16 [01:32].

1931: More than 80 residential institutions were in operation across Canada, the most at any one time [01:50].

Student Resistance: Dozens of fires were set by students across Canada as a form of resistance, with some students reportedly cheering as they watched the schools burn [01:59].

1955: Inuit children were officially included in the residential school system [02:08].

1960s (The "Sixties Scoop"): More than 20,000 Indigenous children were taken from their families by government social workers and placed in foster care or adoption homes, often with non-Indigenous families, leading to a loss of Indigenous language, culture, and identity [02:30].

1966: Twelve-year-old Chanie Wenjack died after escaping from the Cecilia Jeffery residential school. A subsequent investigation found that residential schools caused "tremendous emotional and psychological problems" [02:48].

Closure and Reconciliation

1969: The Canadian government took over responsibility for the remaining schools from the churches [03:04].

1986: Phil Fontaine, head of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, spoke publicly of the abuse he suffered and called for a public inquiry [03:18].

1996: Gordon's residential school was the last federally run school to close [03:33].

2007: The government provided compensation to survivors, including the Common Experience Payment, and established funds for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) [03:49].

2008: Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologized to former students, their families, and communities for Canada's role in the operation of residential schools [04:06].

2015: The TRC released a summary of its findings, including 94 Calls to Action aimed at redressing the legacy of residential schools and assisting in the process of reconciliation. The TRC characterized Canada's treatment of Indigenous people as cultural genocide [04:24].

The video concludes by stating that thousands of children died due to Canada's residential school system, and more than 80,000 survivors and their families continue to live with its legacy [04:54].

video by cbc on residential

What Was the Sixties Scoop?

Period and Scope: Between the 1960s and 1980s, tens of thousands of Indigenous children were taken from their families and placed into the child welfare system [00:04].

Origin of the Term: The term "Sixties Scoop" originated from a B.C. social worker who reportedly felt she was "literally scooping children out of their parents' arms" [00:50].

Continuation of Assimilation: This practice followed the residential school system, which also aimed to assimilate Indigenous children and "solve Canada's Indian problem" [00:21].

Decision-Making: The removals were often carried out by non-Indigenous social workers who lacked understanding of Indigenous culture, family structures, and the role of extended family in childcare [00:57]. Challenges like poverty were often used as justification for removing children [01:15].

Impact and Statistics

Staggering Increase: The number of Indigenous children in the child welfare system spiked significantly. In B.C., for example, First Nations children went from being less than 1% of all kids in foster care in the early 1950s to 34% a decade later [01:30].

Adoptions: Many children were placed for adoption through programs like Saskatchewan's "AIM" program, which advertised kids on TV, radio, and in newspapers [01:53].

Loss of Identity: Almost all adopted kids went to white families in Canada, the United States, and even as far as New Zealand [02:04].

Broken Adoptions: One study found that one-fifth of Indigenous adoptions had broken down by age 15, and half had broken down by age 17 [02:26].

Consequences and Legacy

Cultural Genocide: An influential 1985 report by a Manitoba judge stated that cultural genocide had taken place in a systematic, routine manner [02:48].

Trauma and Loss: Survivors continue to struggle with:

Abuse suffered while in care [03:00].

Loss of family and identity [03:09].

Loss of language and culture [03:12].

Struggles to find their biological families due to a lack of information about where they came from [03:17].

Current Situation: While the era of the Sixties Scoop is over, the removal of Indigenous children continues today. More than half of the kids currently in care in Canada are Indigenous [03:55].

Compensation: The government has agreed to compensate survivors, though this does not include everyone who was affected [03:48].

Charles adn GAF historicla roots article

Historical Foundations of Child and Youth Care

The roots of CYC can be traced back over 150 years along four main paths:

Orphanages (starting in the 1700s):

Initially run by religious orders, lay staff were hired by the mid-1800s as institutions grew.

Many children were not true orphans but "half orphans," placed temporarily due to parental poverty or illness.

Recreational and 'Fresh Air' Movements (mid-1800s to early 1900s):

Organizations like the YMCA, YWCA, and Boys' and Girls' Clubs were founded, in part, to serve young people from the large immigrant population facing poverty.

These community-based programs eventually included residential youth homes for "at risk" youth.

The 'Correction' Movement:

This movement established programs to "correct" perceived deficiencies in children, including the "mad, bad and sad," and those with cognitive or physical disabilities.

Programs included industrial and training schools for juvenile delinquents and institutions for the "mentally or physically deficient," often run by state or provincial governments.

Residential Schools (latter 1800s):

Established for Indigenous youth, these schools were funded by the federal government (in Canada) but run by various religious orders.

The deliberate purpose was to assimilate Aboriginal youth into mainstream society by replacing traditional Indigenous socialization processes with Eurocentric values, essentially creating "cultural orphans".

Note on Early Practice: CYC was born within these institutions and services, and its roots were highly ethnocentric, reflecting the values and beliefs of North America's Anglo-Saxon elites, often being moralistic and exclusionary.

Professionalization and Education

Beginnings of Professionalization: The field's professionalization began in the 1950s with the start of the deinstitutionalization movement. Large institutions were replaced by smaller, specialized treatment facilities, often managed by professional staff.

Recognition of a Discipline: It was within these new programs that CYC began to be recognized as a discipline with specialized skills, leading to a need for specific training and education.

Education: Formal higher educational programs (diploma level) began to blossom in the thirty years surrounding the closure of the old institutions, with the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec being leaders.

Scope: While CYC began in residential care, it has expanded significantly in the last two decades into school, hospital, juvenile justice, and, especially, community-based programming.

Current Challenges Facing the CYC Field

The field faces numerous challenges, largely revolving around recognition and resources:

Lack of Professional Identity and Recognition: CYC lacks a recognized professional identity, leading to a lack of respect from other allied professions and governments. Governments often view CYC as merely a job description.

Low Profile of Associations: Most CYC workers do not belong to a professional association, which limits their budgets and ability to effectively lobby governments for official recognition or mandatory registration.

Poor Pay and High Turnover: CYC is one of the poorest-paid "caring fields" in North America. This leads to high turnover as workers leave for other professions with higher pay and status, often using CYC as a "stepping-stone profession".

Staffing Issues: There is a lack of males in the field, making them hard to recruit and retain, particularly due to the fear of false allegations of abuse.

Financial Cutbacks: Budget cuts have led to the closure or downsizing of programs, forcing young people into services ill-equipped to meet their needs. Cuts to staffing and training budgets compound this, potentially leading to dangerous situations, such as incidents where children have died in care due to improperly trained staff using physical restraints.

Accountability Demands: Governments are increasingly demanding accountability through the development of service standards, accreditation, and outcome measures.

Lack of Common Definition: A lack of a common, clear definition for the field creates confusion with other professions and limits its ability to promote itself.

Ultimately, the core challenge facing CYC is change, particularly the ongoing debate about its professional status, though the true measure of the field lies in meeting its mandate to promote the healthy growth of children and youth.

BUDD chapter 1

This chapter defines reflective practice in the context of Child and Youth Care (CYC) and explains its importance and foundational concepts.

Definition and Rationale

Definition: Reflective practice is an approach that requires CYC practitioners to examine their thoughts and experiences by asking: "What do I know, what do I think I know, and what is there to know?".

Purpose: It is a process of learning through and from moment-to-moment experiences to continuously improve practice and align with professional standards.

Core Principle (John Dewey): "We do not learn from experience we learn from reflecting on experience".

CYC Role Shift: The CYC profession has shifted toward a holistic approach, now requiring practitioners to work not only with children and youth, but also with families and other community professionals. This complexity increases the need for reflective practice.

Key Components of Reflective Practice

Self-Awareness: Learning about self (thoughts, perspectives, values, beliefs, and assumptions) takes precedence over learning about others.

Introspection: Practitioners must develop the skill of introspection, enabling them to notice their internal reactions without letting them influence their actions with others.

Accountability: Reflective practice provides a framework for accountability by questioning one's own understanding, assumptions, and perceived knowledge.

Philosophy: It helps practitioners shift their thinking from a deficit-focused or pathologizing view ("what is wrong?") to a learning-focused view ("what is there to be learned about this other?").

"Right" Action: In complex situations, there is no single "right way" to respond, and the Code of Ethics does not determine one right method. Reflective practice addresses the ambiguous meaning of "the right thing" by requiring practitioners to consider the best interests of the child based on context and individual needs.

Benefits and Characteristics

Reflective practice enables practitioners to:

Monitor, evaluate, and rethink their approach in practice.

Be intentional in decisions and develop awareness of risks and benefits.

Achieve greater accountability in their practice.

Challenge personal and sociocultural assumptions that impact the well-being of others.

Apply learning to future practice and achieve a greater understanding of the experiences of others.

BUDD CHAPTER 11- REFLECTIVE JOURNALS

This chapter introduces the use of reflective journals as a key method for developing critical reflective practice skills in Child and Youth Care.

Rationale and Purpose of Reflective Journals

Journaling as a Tool: Reflective journals are a structured way for practitioners to write about their experiences, clarify their thinking, and focus on a particular issue.

Beyond Retelling: Journal entries go beyond simply retelling an event; they capture the reflective processes of feeling, thinking, interpreting, making sense of, knowledge, and evaluating application to practice.

Continuity: The objective is to establish continuity between experience, reflection, and learning.

Daily vs. Reflective: Daily journals focus on the details of the day. Reflective journals are structured to focus on the practitioner's experience of one particular issue.

Benefits: Reflective journals foster personal insight, reveal evidence of "Reflection in Action and Reflection on Action" models (Schön), enhance understanding of others, and require students to connect experience to theory.

Structured Journaling Guidelines

A structured template helps practitioners remain focused and concise (entries should be no longer than one page). The template generally includes five parts and requires the following steps:

Focus: Clearly and succinctly identify the issue or topic being explored (e.g., "to explore my reaction toward...", "to explore alternative actions...").

The Experience: Briefly describe what happened, who was involved, personal reactions/feelings, and interpretation (meaning) of the other's behaviors.

Your Actions: Describe what was done, the reasons for it, and connect a relevant theory to support the action.

Your Evaluation: Assess the impact of actions on the other, note what worked/didn't work, and identify what needs to be different for next time.

Establishing Further Action & Review: Determine further action required based on the evaluation. Practitioners should return to the journal later to review the entry, identify new insights, and note any emotional tone that may have influenced the initial writing.

Reflective Journals vs. Written Reports

Reflective journals are distinct from formal written reports:

Journal Focus: On you and your experience; uses "I"; includes emotional and cognitive experiences; is a personal narrative.

Report Focus: On the child, youth, or family; uses "This writer"; refrains from including personal emotional/cognitive experiences; is factual documentation based on objective observations.

WSO

The Writing Skills Initiative (WSI) was established in Fall 2008 by the Faculty of Community Services (FCS) at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU).

Program Goal: The WSI was developed to improve writing proficiency among first-year undergraduate students. It was created in response to a 2006 survey where only 69% of respondents felt the university contributed significantly to their clear and effective writing skills.

WSI Lead's Role: The WSI Lead's job is to prepare workshop materials, assess student work to enhance writing skills, provide mentorship, and serve as a liaison to other campus support resources. Their goal is to help de-mystify the university-level writing process.

WSI Lead's Non-Role: The WSI Lead is not responsible for grading essays or exams, nor are they in a position to offer suggestions about course content.

Learning Outcomes: Students are expected to understand writing as a process (including critical thinking, reading, drafting, revision, editing, and reflection), develop their own academic writing practice, adopt transferable skills like conducting literature searches, and reflect on their learning journey.

Academic Integrity

The second major section defines the ethical standards required of students and outlines what constitutes academic misconduct and its consequences.

Definition of Academic Integrity: The term "integrity" comes from the Latin word integritas, meaning wholeness or soundness. To act with academic integrity means to engage in scholarship (such as test-taking and essay writing) with wholeness and as a person adhering to ethical principles. It involves ethical and responsible decision-making.

Definition of Academic Misconduct: This is defined as any action or attempted action that may result in an unfair academic advantage for oneself or an advantage/disadvantage for any other member in the academic community.

Ways Misconduct Occurs: Misconduct can be obvious (like buying an essay online, cheating on an exam, or providing a fake doctor's note) or not-so-obvious (like not citing a source correctly, taking careless notes and forgetting the source, or collaborating on an assignment without permission). Specific examples include:

Plagiarism

Cheating

Misrepresentation of personal identity or performance

Submission of false information

Unauthorized use of intellectual property

Consequences: Consequences can range from a grade reduction/zero grade to more serious offenses like Disciplinary Withdrawal (DW) (permanent withdrawal from a program) or Disciplinary Suspension (DS) (temporary withdrawal). Ignorance of the rules is NOT an excuse.

Intrinsic Motivation/Consequences: Academic dishonesty also has intrinsic consequences, such as violating ethical principles, being unfair to fellow students, degrading the university's reputation, and cheapening the value of one's own degree.

What to Do: Students are advised to:

Become familiar with the Academic Integrity Office at TMU.

Get in the habit of talking to their professors.

Get advice from others on campus, including TAs, Librarians, and Student Learning Support.