chem 107 4/3/25 7.4

1/22

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

23 Terms

Fats Are Solids; Oils are Liquids

Fats, including steak, lard and butter are derived from

animals.

• Oils, like those from corn, soybeans, and peanuts are

derived from plants.

• Both fats and oils belong to a class of hydrolyzable lipids

called triglyercerides.

• Determining a fat versus an oil is as simple as examining

the physical state of the triglycerides at room

temperature – oils are liquids and fats are solids

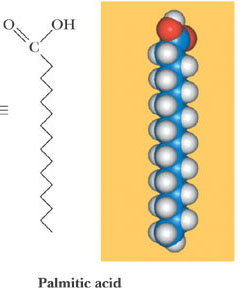

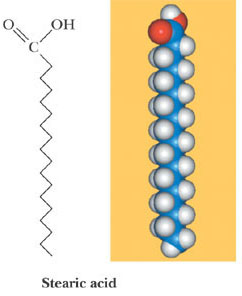

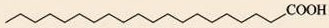

Fatty Acids

A carboxylic acid with a very long hydrocarbon chain!

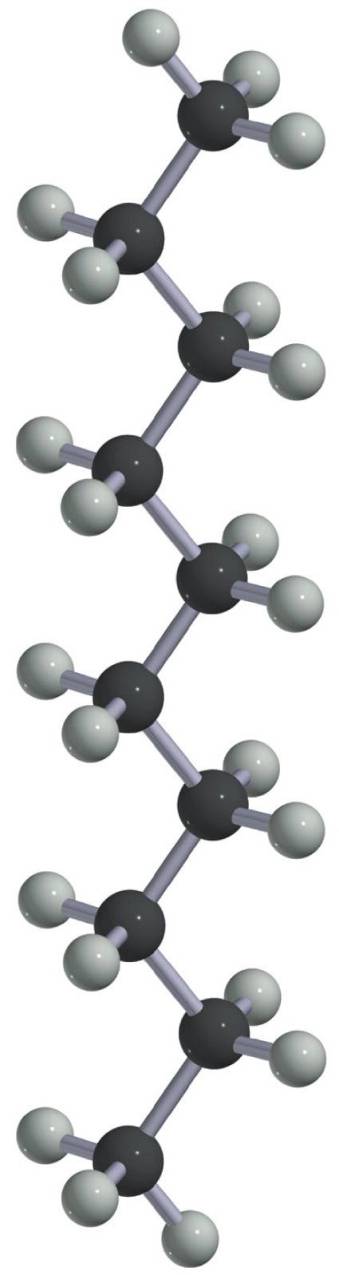

1. Saturated fatty acids1. Saturated fatty acids

– long van der Waal zippers!!

Conformational Isomers

Fatty Acids

Naturally occurring fatty acids

• Usually have an even number of carbon atoms

• Usually are unbranched

Fatty Acids

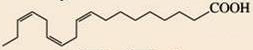

A carboxylic acid with a very long hydrocarbon chain!

1. Saturated fatty acids1. Saturated fatty acids

– long van der Waal zippers!!long van der Waal zippers!!

2. Unsaturated fatty acids2. Unsaturated fatty acids

Unsaturated Acids

Unsaturated Hydrocarbons

Intermolecular interaction = van der Waal forces

Unsaturated Hydrocarbons

Unsaturated Hydrocarbons

Fatty Acids

. Naturally occurring fatty acids

• Usually have an even number of carbon atoms

• Usually are unbranched

• Unsaturation isomers are cis C=C

Dietary Lipids

The oil has many unsaturated cis carbon-carbon double

bonds in the hydrocarbon tail.

Dietary Lipids

In the ball-and-stick model of the fat, notice that the tails

are physically close to each other.

• This proximity creates disturbances in the electron

distribution around each of the tails as they interact with

each other.

• These disturbances result in London forces – the tails of

the fat are attracted to each other.

• These mostly straight-chain tails allow for many surface

contacts, which increases the attractions between the tails

and restricts the molecular motion, allowing the molecules

to form a solid or a semisolid.

Dietary Lipids

Look at the ball-and-stick model of the oil molecule.

• It has many unsaturated cis carbon-carbon double bonds in the hydrocarbon

tails, making it polyunsaturated.

• Notice how the cis double bonds in the tails of the oil creates kinks in the

otherwise straight hydrocarbon chain.

• The kinked tails interact less with each other through London forces because

the tails of the unsaturated oil cannot stack together as closely as those in the

fat can.

• Less London force attractions means that the hydrocarbon chains in the oil

move more freely.

• The greater molecular motion among the hydrocarbon tails in an oil does not

allow enough stacking of the tails for a solid to form at room temperature.

Attractive Forces and the Cell

Attractive Forces and the Cell Membrane

A Look at Phospholipids

• The main structural components of cell membranes are called

phospholipids.

• Phospholipids have a glycerol backbone with fatty acids linked

to it through an ester bond.

• Phospholipids have only two fatty acids on their glycerol

backbone. The third OH group of the glycerol is bonded to a

phosphate-containing group.

• The phosphate-containing group is ionic (polar).

• The fatty-acid tails are nonpolar.

Attractive Forces and the Cell

Membrane (2 of 9)

A Look at Phospholipids

There are many different phospholipids, but they all share

this similar structure: a glycerol backbone with two nonpolar

fatty acid tails and a polar phosphate-containing head.

• The two tails of the phospholipid affect the overall shape of

the molecule.

• Phospholipids have a cylindrical shape with a much

larger head group, which hinders their ability to form

micelles.

The Cell Membrane Is a Bilayer

A cell membrane composed of phospholipids cannot exist as

a single layer.

• The phospholipid bilayer is the structural foundation for a

cell’s membrane.

• Instead, the phospholipids form a double layer called a

bilayer.

• The polar heads are directed out into the surrounding aqueous

environment and into the aqueous interior of the cell.

• This arrangement leaves the hydrophobic tails of both layers

directed toward each other, creating a nonpolar interior region.

Attractive Forces and the Cell

Attractive Forces and the cell Membrane (5 of 9)

Attractive Forces and the Cell Membrane (6 of 9)

Protein molecules can span the bilayer (integral membrane

proteins) or associate with one hydrophilic surface of the bilayer

(peripheral membrane proteins).

• Proteins are the membrane’s functional components, allowing

selected molecules to move into and out of the cell.

• The exterior surface of the cell membrane also contains

carbohydrates that act as cell signals.

• The fluid mosaic model creates “icebergs” of protein floating in

a “sea” of lipids.

• The membrane is fluidlike: The phospholipids move freely within

their bilayer.

7.5 Attractive Forces and the Cell Membrane (7 of 9)

Attractive Forces and the Cell Membrane

(8 of 9)

Steroids in Membranes: Cholesterol

Cholesterol is a steroid.

• Steroids are lipids with a structure that

contains a four-membered fused ring called

a steroid nucleus.

• Even though the steroid structure differs

greatly from the structures of fatty acids

and triglycerides, steroids are classified

as lipids based on their nonpolar

nature.

• These molecules have a variety of

functions in the body, including regulating

sexual development (testosterone and

estrogens) and emulsifying dietary fats

(bile acids).

7.5 Attractive Forces and the Cell

Membrane (9 of 9)

Steroids in Membranes: Cholesterol

• Cholesterol contains the steroid nucleus with a polar end.

• Cholesterol situates itself in the phospholipid bilayer so that the -OH

group protrudes out into the aqueous

environment, while the rest of the

molecule nestles in the nonpolar

interior of the membrane.

• Cholesterol can slip in between the

saturated hydrocarbon tails of

phospholipids, increasing fluidity.

• Cholesterol can also interact with

unsaturated tails, increasing the

rigidity of the membrane.