Booklet 11 - Fiscal Policy

1/43

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

44 Terms

What do you Discuss when Asked About - The Concept of Fiscal Policy

Define Fiscal Policy

Define Budget Revenue Receipts

Define Budget Expenses (Outlays)

Define Fiscal Policy

A macroeconomic or aggregate demand management strategy involving government’s estimates of the expected value of its receipts and the expected values of its outlays usually based on a one-year period

Define Budget Revenue Receipts

The government's projected income from its core, recurring activities that do not create a future obligation or reduce assets

Define Budget Expenses (Outlays)

The money a person or organization spends on goods and services

The Macroeconomic Policy Objectives of the Australia Government

Price Stability

Indicator - Inflation

Target - 2-3%

Current Level - 3.2% (September Quarter)

Full Employment

Indicator - Unemployment Rate

Target - 4-4.5%

Current Level - 4.2% (June 2025)

Sustainable Economic Growth

Indicator - GDP Growth Rate (Annual)

Target - 3-3.5%

Current Level - 1.3% (March qtr 2025)

Equitable Distribution of Income

Indicator - Gini Coefficient (0=More Equitable, 1=Less Equitable)

Target - Decreasing/Low

Current Level - Decreasing

Efficient Allocation of Resources

Indicator - Labour Productivity (LP) or Multifactor Productivity (MFP)

Target - Increasing

Current Level - Increasing

Discuss Price Stability as a Macroeconomic Objective of the Australian Government

Price stability is a key macroeconomic objective of the Australian Government, aiming to maintain a sustained and moderate increase in the general price level, with the inflation target set at 2–3%. Complete elimination of inflation is neither feasible nor desirable, and moderate inflation helps avoid deflation while minimising distortions in the economy. Controlling inflation is crucial because high inflation erodes the purchasing power of households and firms, reduces international competitiveness, and alters income distribution. For example, inflation peaked at 7.8% in December 2022, reflecting recent cost pressures. The costs of high inflation include increased living costs and reduced household real incomes, higher interest rates through contractionary monetary policy which dampens consumption and investment, and reduced confidence in money as a store of value, leading households to invest in appreciating assets instead of productive investment. Additionally, high inflation makes business planning difficult, decreases export competitiveness, exacerbates income inequality (particularly affecting households on fixed incomes like JobSeeker), and leads to bracket creep, where higher marginal tax rates reduce disposable income. Overall, maintaining price stability protects living standards, encourages productive investment, and supports sustainable economic growth.

Discuss Full Employment as a Macroeconomic Objective of the Australian Government

Full employment is a key macroeconomic objective of the Australian Government, defined as a situation where all willing workers can find jobs and the economy operates at full capacity, with cyclical unemployment at 0% while only structural and frictional unemployment remain. Achieving 0% unemployment is impossible due to the ongoing presence of frictional and structural unemployment, which have long-term benefits: structural unemployment allows workers to retrain or upskill and shift to more efficient sectors, increasing overall productivity, while frictional unemployment occurs naturally as workers transition between jobs, often improving work conditions and efficiency. Full employment ensures the efficient use of labour resources, reduces government expenditure on transfer payments, and increases tax revenue, supporting economic growth at or near its optimum level. Conversely, unemployment lowers household living standards, reduces consumption spending and business confidence, decreases investment, increases government transfer payments, and reduces income tax revenue, highlighting the importance of maintaining a strong labour market.

Discuss Sustainable Economic Growth as a Macroeconomic Objective of the Australian Government

Sustainable economic growth is a key macroeconomic objective of the Australian Government, defined as the increasing capacity of the economy to satisfy the wants of its members, measured by the rate of change in real GDP, with the desirable target range being 3–3.5% per year. Sustainable growth balances economic expansion with social and environmental considerations, such as healthcare, education, and social equity, ensuring that improvements in current living standards do not compromise the wellbeing of future generations. Achieving sustainable economic growth raises national income and average living standards, increases employment and reduces cyclical unemployment, improves the quality of goods and services produced, and boosts government revenue through higher taxation while reducing the need for transfer payments. However, unsustainable growth can create risks, including inflation beyond the target range, environmental degradation, increased income inequality, and rapid structural changes in the economy, highlighting the need for a measured and balanced approach to economic expansion.

Discuss Equitable Distribution of Income as a Macroeconomic Objective of the Australian Government

Equitable distribution of income is a key macroeconomic objective of the Australian Government, aimed at creating a fairer allocation of wealth and opportunities within the economy. The government uses progressive taxation to levy higher tax rates on high-income earners while providing social security payments to lower-income households, reducing income inequality and shifting the Lorenz curve closer to the line of equality, thereby lowering the Gini coefficient. Additionally, the government redistributes income through indirect measures such as public services, including healthcare and education, ensuring that all Australians have access to essential services regardless of income. These policies aim to correct market inequities and promote social welfare while supporting overall economic stability.

Discuss Efficient Allocation of Resources as a Macroeconomic Objective of the Australian Government

Efficient allocation of resources is a macroeconomic objective of the Australian Government aimed at maximising the satisfaction of consumers’ wants and needs. This involves achieving technical efficiency, where goods and services are produced at the lowest possible cost; allocative efficiency, where resources are employed to minimise opportunity costs; and dynamic efficiency, which ensures the economy can adapt over time to changing conditions. By promoting efficiency, the government supports higher productivity, better use of scarce resources, and sustainable economic growth, ultimately improving living standards and overall economic welfare.

What do you Discuss when Asked About - The Different Budget Outcomes i.e., Balanced, Surplus, & Deficit Budgets

Balanced Budget - Revenue = Expenditure

Budget Deficit - Revenue < Expenditure

Budget Surplus - Revenue > Expenditure

Discuss a Balanced Budget Outcome

Most governments tried to run balanced budgets. This is when the expected revenues and expenditures are nearly equal. This also a neutral stance of fiscal policy. Meaning this stance will have a neutral effect on the level of economic activity as the budget balance is zero.

This is used by government to set a neutral stance

For example the 2002-03 budget

Discuss a Budget Deficit Outcome

In this case, the anticipated expenditure/outlay is greater than the expected receipts/revenue. Once again, in a very traditional sense, the government would run a deficit (or expansionary stance) budget when it was felt that the economy needed extra support to smooth out economic fluctuations and to achieve its economic objectives. By spending more than they collect, the government is injecting extra funds into the economy, which can then be used to create jobs or distributed as transfer payments

This is used by government to set an expansionary stance

For example the 2025-26 budget

Discuss a Budget Surplus Outcome

This is when the anticipated revenues/receipts exceed the expected expenditure/outlays. In other words, the government will have some money left over at the end of the year. In a traditional Keynesian approach, the government would run a surplus (or contractionary stance) budget when the economy was strong, and it was felt that no extra stimulus was necessary.

This is used by government to set a contractionary stance

For example the 2023-24 budget

Reasons for Differences between Planned & Actual Budget Outcomes

Differences between planned and actual budget outcomes arise primarily due to changes in economic conditions and unforeseen external events. Governments base their budgets on forecasts of economic indicators such as unemployment, inflation, real GDP, and aggregate expenditure. However, shifts in these factors can alter revenue and expenditure levels. For instance, during economic downturns, consumption and investment fall, reducing taxation revenue while increasing government spending on support measures, as seen during the 2020 COVID-19 lockdowns with JobKeeper and JobSeeker payments. External events, such as natural disasters or commodity price fluctuations, can also affect outcomes; for example, the Queensland floods of 2021–22 required additional spending, while higher commodity prices in 2022–23 increased revenue through GST collections. Such variations can substantially alter budget results, illustrated by the 2019–20 budget, which shifted from a planned $7.1 billion surplus to an actual $85.3 billion deficit due to the pandemic and global economic events.

What do you Discuss when Asked About - Distinction Between Automatic Fiscal Stabilisers and Discretionary Fiscal Policy

Describe Discretionary Stabilisers (Structural)

Describe Automatic Stabilisers (Cyclical)

Describe the Two Main Automatic Stabilisers

Progressive Taxation System

Unemployment Benefits (Transfer Payments)

Describe Discretionary Stabilisers (Structural)

Discretionary stabilisers, or discretionary fiscal policy, are deliberate changes by the government to spending or taxation aimed at influencing economic activity. These include decisions such as increasing spending on infrastructure, defence, or public projects, as well as altering tax rates like marginal personal income tax or excise duties. For example, the Federal Government contributed $1.7 billion to WA’s Metronet infrastructure project, and in July 2019 implemented large cuts to marginal personal income tax rates. Discretionary measures are often used when automatic stabilisers are insufficient to manage severe recessions or economic booms. The structural balance, which reflects the difference between government structural spending (e.g., providing public goods) and the tax revenue raised, incorporates these discretionary changes. Such measures directly impact the budget outcome; for instance, tax cuts or increased spending can reduce a budget surplus or increase a deficit.

Describe Automatic Stabilisers (Cyclical)

Automatic stabilisers (also called built-in or cyclical stabilisers) are components of the budget (tax receipts and welfare payments) that automatically change due to changes in the business cycle.

They are called automatic stabilisers because they operate in a countercyclical way without the Treasurer deliberately changing their level or announcing new policies.

Describe the Two Main Automatic Stabilisers

Progressive Taxation System

The progressive tax system is an automatic stabiliser that adjusts tax revenue in response to changes in household incomes, helping to smooth fluctuations in aggregate demand. In a boom, as incomes rise, taxpayers move into higher tax brackets and pay a larger proportion of their income in tax, which reduces disposable income and slows the growth of aggregate demand, moderating the boom. Conversely, during a recession, incomes fall and individuals pay a lower proportion of their income in tax, leaving households with relatively more disposable income to sustain consumption and support aggregate demand. This counter-cyclical effect helps stabilise the economy without the need for deliberate government intervention.

Unemployment Benefits (Transfer Payments)

Unemployment benefits, also known as transfer payments, are an automatic stabiliser that helps moderate fluctuations in the economy by adjusting government spending in response to changes in unemployment. When economic activity falls and the economy enters a recession, unemployment rises, leading to higher government expenditure on unemployment benefits. This increase in spending supports household incomes, sustaining consumption and aggregate demand. Conversely, when the economy is growing and unemployment decreases, spending on benefits falls, helping to contain aggregate demand and reduce inflationary pressures. These payments operate automatically, cushioning the economy without requiring new government decisions.

What do you Discuss when Asked About - Methods of Financing a Budget Deficit

Borrowing Domestically by Issuing Bonds to the Private Sector

Advantages of Borrowing from the Private Sector

Disadvantages of Borrowing from the Private Sector

Borrowing from the Overseas Sector by Issuing Government Bonds

Advantages of Borrowing from the Overseas Sector

Disadvantages of Borrowing from the Overseas Sector

Discuss Borrowing Domestically by Issuing Bonds to the Private Sector as a Method of Financing a Budget Deficit

Borrowing from the private sector through the issuance of Commonwealth Government Securities (CGS), or government bonds, is a key method for financing a budget deficit. The government sells bonds to raise funds, committing to repay the principal with interest at a set future date. During a recession, this allows the government to stimulate economic activity by injecting funds into the economy for expenditure programs. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Federal Government used bond issuance to finance deficit spending. Commercial banks, such as CommBank, NAB, Westpac, and ANZ, assist in selling these securities, depositing the proceeds into the government’s account. This method is effective as funds withdrawn from the private sector are reintroduced into the economy through government spending

Advantages:

No Change in the Money Supply: It does not change the money supply, so it is non-inflationary. Funds withdrawn by households and firms to purchase bonds are returned to the banking system when the government spends on projects, such as infrastructure, maintaining overall liquidity.

Does not Increase Foreign Debt: It does not increase foreign debt, as the borrowing occurs domestically. The government does not owe money to overseas residents, avoiding a direct impact on the current account balance.

Disadvantages:

Crowding Out: It can cause crowding out, where government borrowing increases competition for funds, driving up interest rates. Higher rates make it more expensive for businesses to borrow, reducing private investment, while also potentially appreciating the AUD, which decreases export competitiveness and increases imports, widening the current account deficit.

Increase in Public Debt: It increases public debt, creating future obligations for the government to repay both principal and interest, which can strain future budgets and limit fiscal flexibility.

Discuss Borrowing from the Overseas Sector by Issuing Government Bonds as a Method of Financing a Budget Deficit

The government can also borrow from its overseas financial markets by getting the RBA to sell new CGS to overseas investors. The RBA credits the government’s account with the size of the deficit.

Advantages:

The main advantage is that there is no increase in domestic interest rates, hence no domestic inflationary pressures

Disadvantages:

As the Government borrows from overseas, it increases the level of foreign debt for the country. When the RBA sells its bonds at high interest rates to attract foreign investors to fund their expenditure, the government is also obliged to return the debt with interest payments. This debt interest payment will flow out of the country from the Income category of the Current Account and this leads to an increase in CAD.

Discuss Borrowing from the RBA as a Method of Financing a Budget Deficit

The government can borrow from the RBA by requesting the RBA to print money to cover the shortfall in budget revenue. This involves the government selling new CGS or bonds to the RBA, which it is obliged to buy. The RBA credits the government’s account with the money. This is known as monetary financing or “printing money”.

Advantages:

There is no change in interest rates

There is no public debt. (i.e the Government does not owe the private sector any money

Disadvantages:

This increases the money supply (more currency circulating) and could lead to inflation if the economy was operating at full employment.

If done too frequently, it causes a loss of confidence in the government’s economic management. The Australian government no longer uses monetary financing.

Discuss Selling Government Assets as a Method of Financing a Budget Deficit

The government can sell public assets and property as a way to raise revenue to fund there government debt. This can include privatising certain government businesses enterprises such as when the Australian government privatised the Commonwealth Bank and Qantas or selling public land and/or buildings.

Advantages:

There is no debt obligation as the government is not borrowing money, meaning there are no long term repayments.

It can improve the productivity/efficiency of the industry as private firms are incentivised through the profit motive.

Provides the government with future revenue through company tax revenue

Disadvantages:

It is limited to what the government owns and cannot be sold a second time.

Low-income earners who relied on subsidised government services are impacted as they may be priced out of the market

What do you Discuss when Asked Abou the Impact of Government Debt

Describe the Overview

Impacts:

Future Tax Burden

Ongoing Interest Payments

Lack of Spending Restraint

Crowding Out of Private Investment

Economic Drag from High Debt Levels

Overview of the Impacts of Government Debt

Government debt has significant economic implications. Since 2008, Australia experienced consecutive budget deficits, causing Commonwealth Government debt to rise from $369 billion in 2015 to $904 billion in 2024, equivalent to 34% of GDP. Debt is projected to reach 35.5% of GDP by 2025-26, with interest repayments increasing from $26.3 billion to $36.6 billion by 2028-29. High debt levels create opportunity costs, as funds spent on interest could otherwise be invested in infrastructure, healthcare, or education. Debt also increases fiscal vulnerability during economic shocks. While current debt levels are the highest since the 1950s, they remain below post-World War II peaks and lower than many other developed nations, indicating manageable relative risk.

Discuss the Future Tax Burden as an Impact of Government Debt

Government debt must be repaid by future taxpayers, potentially requiring higher taxes or lower government spending in the future limiting the government’s ability to act on unexpected exogenous events. A significant portion of Australian government bonds is owned by non-residents, meaning future wealth is transferred abroad

Discuss the Ongoing Interest Payments as an Impact of Government Debt

Interest payments on debt are a continuous cost for taxpayers. These payments represent an opportunity cost, limiting spending or tax reduction options. Rising interest rates will increase these costs over time. This will impact future economic growth prospects.

Discuss the Lack of Spending Restraint as an Impact of Government Debt

Deficit spending removes political restraints on government expenditure, leading to potentially wasteful spending. Government spending reallocates resources from the private sector to less efficient public sector uses

Discuss the Crowding Out of Private Investment as an Impact of Government Debt

Issuing government debt by selling bonds can increase interest rates, reducing private investment and economic growth. This contributes towards the crowding out effect as it discourages private investment. The Reserve Bank of Australia's policies currently mitigate this effect, but inflation risks may force higher interest rates in the future

Discuss the Economic Drag from High Debt Levels as an Impact of Government Debt

High levels of debt can slow economic growth, leading to higher unemployment and lower wages. While Australia's debt is lower than some countries, its steady increase is concerning for long-term economic health

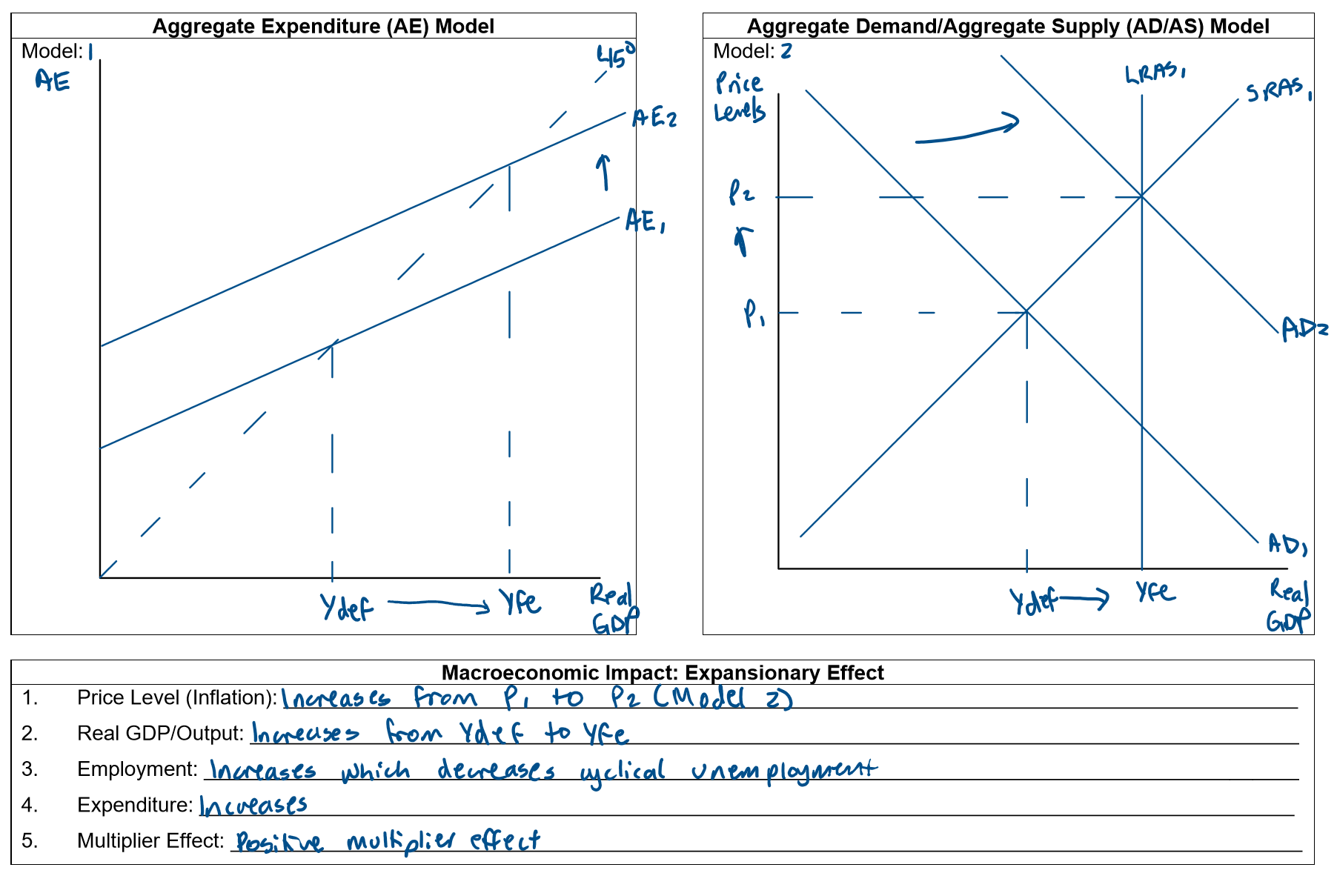

The Impact of Expansionary Fiscal Policy Stances on the Level of Economic Activity Using the AE and the AD/AS Model

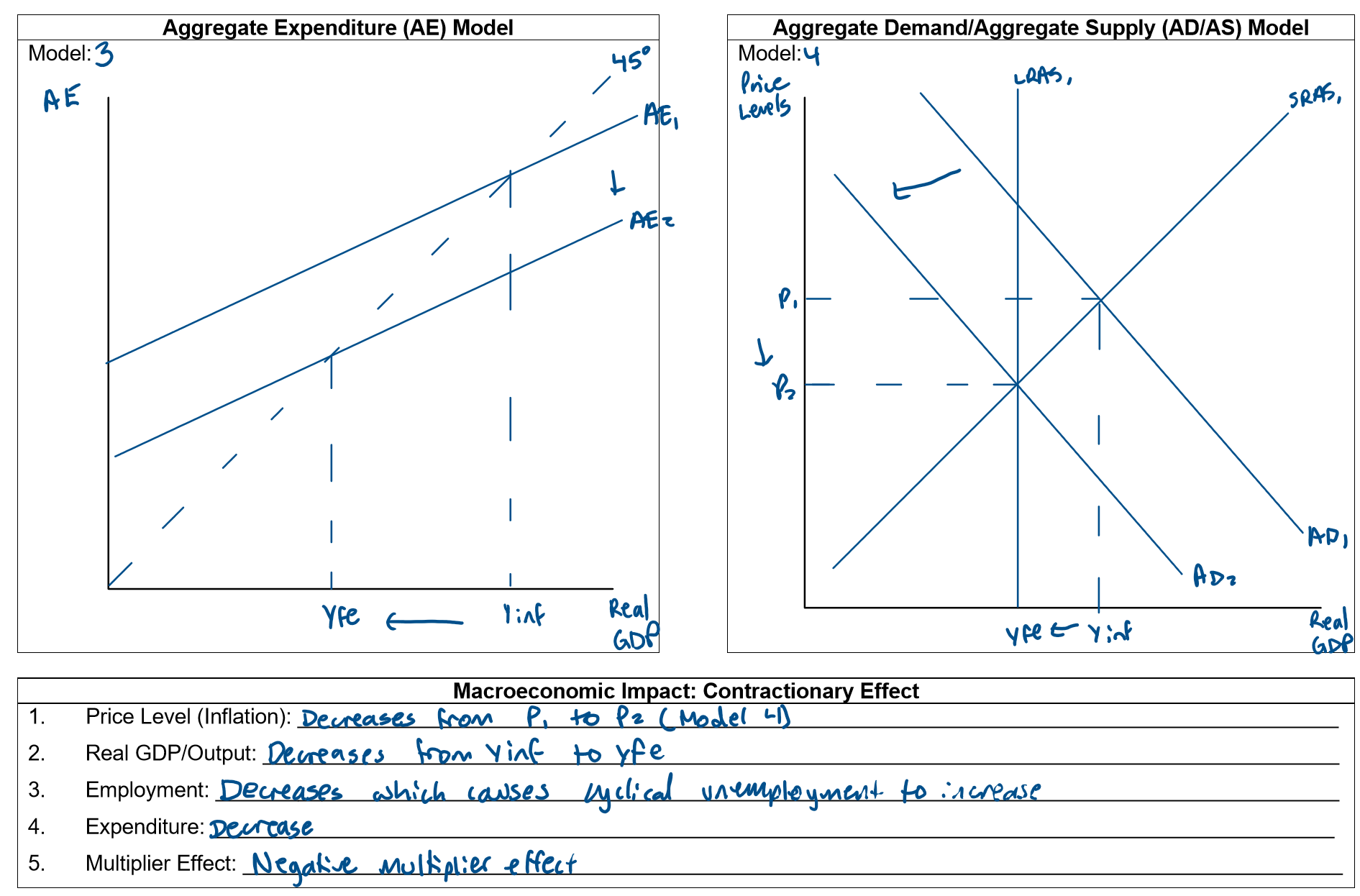

The Impact of Contractionary Fiscal Policy Stances on the Level of Economic Activity Using the AE and the AD/AS Model

What do you Discuss when Asked About - The Strengths of Fiscal Policy

Selective

Short Outside Time Lag

Effective in a Recession

Stabilising Effect

Discuss ‘Selective’ as a Strength of Fiscal Policy

A key strength of fiscal policy is its selectivity, as the government can direct spending and taxation to specific sectors of the economy to achieve desired outcomes. This allows resources to be allocated where the multiplier effect is highest, stimulating economic activity efficiently. For example, in the 2008–2009 Budget following the Global Financial Crisis, the Australian Government increased funding for school construction, directly targeting the construction industry to boost employment and economic growth.

Discuss ‘Short Outside Time Lag’ as a Strength of Fiscal Policy

A strength of fiscal policy is its short outside time lag, as changes in government spending or taxation can take effect almost immediately. For example, the excise fuel tax moratorium in the 2022–23 Budget was enacted within days, quickly increasing household disposable income and influencing consumption and savings patterns.

Discuss ‘Effective in a Recession’ as a Strength of Fiscal Policy

Fiscal policy is effective in a recession because the government can inject funds to boost aggregate demand, stimulating the multiplier effect, which increases consumption, employment, and income. For example, during the 2020 recession, the government expanded transfer payments to households (JobSeeker) and subsidies to businesses (JobKeeper) to support economic activity during the pandemic.

Discuss ‘Stabilising Effect’ as a Strength of Fiscal Policy

Fiscal policy has a stabilising effect because automatic and discretionary stabilisers work together to moderate fluctuations in economic activity. In booms, they dampen spending and curb inflation, while in downturns, they stimulate spending and support aggregate demand. For example, during the mining boom (2003–2013), bracket creep pushed households into higher tax brackets, increasing tax payments and slowing the growth of AD, which helped stabilise the economy and contain inflation.

What do you Discuss when Asked About - Weaknesses of Fiscal Policy

Inside Time Lag

Relatively Inflexible

Crowding Out

Political Constraints

Discuss ‘Inside Time Lag’ as a Weakness of Fiscal Policy

A key weakness of fiscal policy is its long inside time lag, which is the delay between recognising an economic problem and implementing a budget response. Since the federal budget is typically handed down once per year, this can slow the policy’s responsiveness. For example, although the government reacted quickly to COVID-19 in the 2020–21 budget, such timely intervention is not always possible, meaning fiscal policy may sometimes fail to address economic issues promptly.

Discuss ‘Relatively Inflexible’ as a Weakness of Fiscal Policy

A key weakness of fiscal policy is that it is relatively inflexible due to social and political constraints. For instance, during the Mining Boom, reducing spending on popular areas like defence or health to cool the economy would have been economically effective but politically and socially unacceptable. Similarly, increasing welfare spending during a recession may reduce work incentives, limiting the policy’s effectiveness.

Discuss ‘Crowding Out’ as a Weakness of Fiscal Policy

Crowding out is a weakness of fiscal policy that occurs when increased government spending reduces private sector activity. For example, during a recession, an expansionary budget funded by selling Commonwealth Government Securities (bonds) can push up interest rates, making private borrowing more expensive. This can dampen private investment, producing a contractionary effect that opposes the intended stimulus of the budget.

Discuss ‘Political Constraints’ as a Weakness of Fiscal Policy

Political constraints are a weakness of fiscal policy because governments may avoid necessary but unpopular measures, such as raising taxes, due to electoral considerations. For example, the tax cuts implemented in the 2024‑25 budget may have been politically motivated ahead of the 2025 election, rather than based on the optimal economic need, limiting the effectiveness of fiscal policy.

Fiscal Policy Stances in Australia over the Last 3 Years

Over the last three years, Australia’s fiscal policy has shifted in response to evolving economic conditions. In the 2023‑24 Budget, the government adopted a contractionary stance with a planned and actual budget surplus, marking the first surplus since 2007. This reflected the economy’s recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and strong commodity prices, allowing the Albanese Government to focus on responsible spending. Key measures included continued infrastructure investment to boost economic growth and create jobs, targeted support for sectors still affected by COVID‑19 such as tourism and education, and programs aimed at job creation and skills training.

In contrast, the 2024‑25 Budget took an expansionary stance with a planned and actual deficit, driven by Stage Three tax cuts effective from 1 July 2024, reducing marginal tax rates and eliminating one tax bracket. Additional measures included electricity subsidies for households and small businesses to address the cost of living crisis, $6.2 billion invested to deliver 40,000 social and affordable homes, and extensions of the $20,000 instant asset write-off for small businesses along with tax incentives for hydrogen and critical minerals production.

Looking ahead, the 2025‑26 Budget continues an expansionary stance, with a forecasted deficit of $42.1 billion, reflecting structural reforms to the NDIS and aged care and reduced interest costs. The budget extends cost-of-living relief through new personal income tax cuts, energy bill subsidies, investment in 1.2 million new homes, increased childcare subsidies, reduced compulsory HEC repayments, and 10,000 free TAFE places. Productivity-enhancing measures include investment in green metals and manufacturing, competition reforms, and extending Medicare via expanded bulk-billing eligibility and hospital and urgent care investments.

Overall, fiscal policy over the last three years has been flexible, alternating between contractionary and expansionary stances to balance economic recovery, cost-of-living pressures, and long-term structural reforms.