Human Rights & Wrongs

1/79

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

80 Terms

Assertive exercise (Donnelly)

Right is claimed, often when it is threatened or denied (e.g., “I have a right to an attorney”)

Active respect

Duty-bearer respects the right without it being claimed (e.g., “You have a right to remain silent”)

Objective enjoyment

Right is enjoyed without either side consciously thinking about it (e.g., “A person goes about daily life, not being arbitrarily arrested or detained”)

What is the source of human rights according to Donnelly?

Inherent dignity:

Donnelly's view is that human rights are grounded in the unique and inherent dignity of each person.

Universal and inalienable:

This dignity is a universal feature of humanity, meaning the rights it confers are also universal and cannot be forfeited.

Transcends cultural differences:

The universality of human rights means they are not a Western construct and transcend cultural, political, or social boundaries. He argues against cultural relativism as a justification for human rights abuses.

Possession Paradox

having a right is most valuable precisely when you don’t have it.

Sikkink’s position

human rights are historically contingent, diverse, and politically constructed.

Donnelly’s position

human rights are rooted in moral nature and universality.

Sikkink tries to debunk:

The story that Sikkink tries to debunk is this:

• Human rights stem from human dignity—a notion rooted in

natural law (later infused with Christian theology).

• There are universal moral principles inherent in human nature, and we

can discover them through reason.

• With the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, a shift away from the concept of

natural law occurred. Man-made law (positive law) and sovereignty

became dominant.

• This dominance dissipated for a short while after World War II, when

human rights were prescribed against the evils of manmade law (i.e., Nazi

law). Positive law resurfaced again.

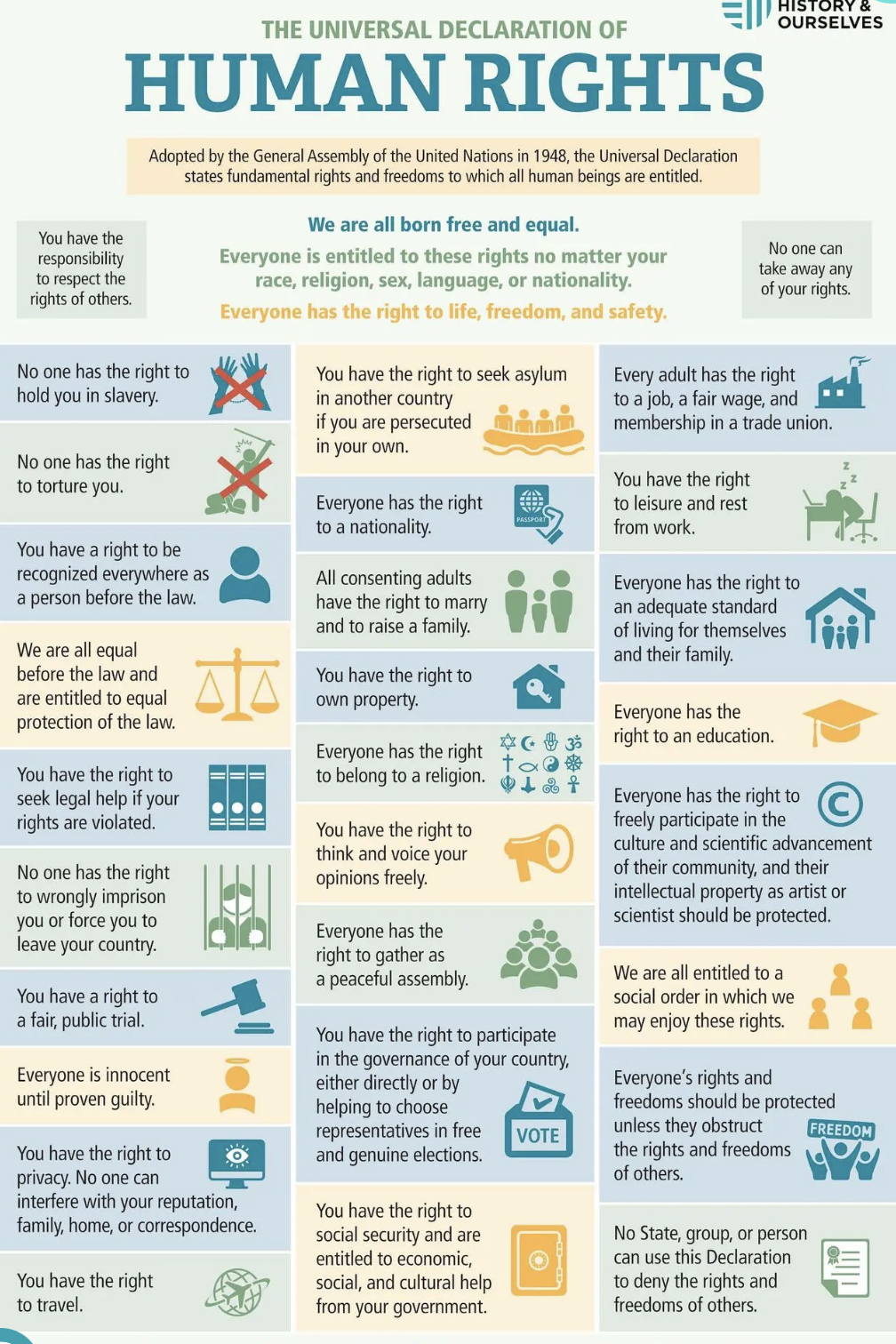

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

adopted in 1948, that declares the universal human rights and fundamental freedoms to which every individual is entitled, regardless of background. Outlining 30 articles on rights like freedom from torture and the right to education, it was created post-WWII to prevent future atrocities and serves as a global standard and inspiration for human rights treaties, laws, and systems worldwide.

Guarantees fundamental rights such as the right to life, liberty, and security, freedom from slavery and torture, freedom of expression and religion, the right to education, and economic, social, and cultural rights.

Borgwardt (2005)

explaining the US’s involvement in the creation

of post-WWII order

Van Boven (2016)

explaining the Cold War tensions and

expansion of rights and human rights treaties

Key debates of 1950s—1960s:

• Universalism vs (cultural) relativism

• Civil/political rights vs economic/social rights

• Individual rights v. group rights

• Outcome = fragmentation

Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907

initiated by Czar Nicolas II of Russia and involved European and non-European

states:

• A series of agreement to establish rules and regulations to conduct warfare, protect civilians and combatants during conflict

• Creation of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (1899) – still exists

What happened after WWI?

League of Nations

• Permanent Court of International Justice

• Mandates system (manage colonialism)

Failed attempts to prohibit war

• League of Nations (ineffective) sanctions

• League of Nations’ inability to protect minorities and refugees

League of Nations

The League of Nations established in 1920 as centerpiece of President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points (1918) → vision of a

new international order.

• Core ideas: collective security, self determination, open diplomacy, disarmament, international cooperation.

• Main principles: territorial integrity, independence of sovereign states, and alternative dispute resolutions.

• Failed to act decisively against the Italian and Japanese aggression in the 1930s and couldn’t protect minorities, especially European Jews.

League of Nation’s failure (Bogwardt)

One of the main reasons is the US was not on board, and the institution had weak enforcement power.

• Despite Wilson’s role, the US never joined:

• Senate rejected the initiative due to concerns over losing sovereignty,

entanglement in foreign wars.

• The League seemed too much like an external restraint on US autonomy.

• Domestic politics mattered: partisan opposition to Wilson killed the

membership bid.

• Result: US absence weakened the League’s credibility and effectiveness.

Kellogg-Briand Pact (1928)

French- and US-led initiative outlawing war as a tool of national policy.

• Symbol of American legalist–moralist diplomacy.

• Laid groundwork for “crime of aggression” later at Nuremberg

The Atlantic Charter (1941)

Joint declaration by FDR and Churchill.

• Principles: self-determination, free trade, social security, peace.

• Framed as a New Deal for the world —linking US domestic reform ideals

to international order.

After WW II

United Nations

• International Court of Justice

• Trusteeship system (decolonization)

• Emphasis on “universal” values

• Universal Declaration of Human Rights with diverse origins (see Sikkink’s chapter)

• Genocide Convention of 1948

Why the US eventually joined the United Nations?

FDR’s vision: rooted in a New Deal idiom — pragmatic, institution-

building, tying global order to welfare and security.Framed UN not as a supranational body but as a cooperative

framework that preserved US leadership.WWII experience changed US attitudes: Pearl Harbor shattered

isolationism, showing global interdependence.US elites had learned from Wilson’s failure: broad public outreach,

bipartisan support, and framing UN as tool for US national interest.The UN structure (Security Council, veto power) reassured the US that

it would retain decisive control.

How did US domestic politics (isolationism, racism, New Deal reforms) shape its international vision?

US domestic politics, including isolationism, racism, and the New Deal reforms, profoundly shaped its international vision by creating internal contradictions that simultaneously drew the nation toward and repelled it from global leadership

This dynamic, particularly in the interwar years and following World War II, meant that the US often promoted democracy abroad while failing to address injustice at home.

Where do you see continuity with Wilsonian principles?

The United Nations: The creation of the United Nations after World War II is the most prominent example of continuity with Wilsonian ideals. It addressed the flaws of Wilson's original League of Nations by establishing a more robust system for collective security, dispute resolution, and international law.

International institutions: The post-World War II global order, built around institutions like the World Trade Organization and the International Court of Justice, formalized Wilson's vision of a rules-based order for international relations.

Collective security: The principle that an attack on one member of an alliance is an attack on all—a foundation of NATO—echoes Wilson's idea that nations should act collectively to enforce peace.

Open Diplomacy & Democratic enlargement

Where do you see rupture in Wilsonian Principles?

"America First" policies: The election of Donald Trump in 2016 marked a significant rupture with Wilsonianism. His "America First" doctrine, which prioritized national interests over international cooperation, challenged the multilateral foundations that Wilson helped to establish.

Withdrawal from international agreements: Trump's withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement and the Iran nuclear deal, along with his criticism of NATO and the WTO, represented a direct retreat from global leadership and international institutions.

Erosion of the global middle class: The decline of the middle class in many parts of the world, particularly in the West, threatens the appeal of liberal globalization and the Wilsonian idea of a global, interconnected economy.

Nationalism, redrawing borders caused ethnic conflict

Can we consider the US in the 1940s a “reluctant hegemon” or an “architect of order”?

US role in the 1940s is best described as both a reluctant hegemon and a deliberate architect of order.

"reluctant hegemon" characterization applies to the US's posture at the start of the decade, reflecting a deep-seated tradition of isolationism that existed before World War II.

After becoming fully engaged in the war, the US consciously pivoted toward establishing and enforcing a new international order. The devastating experience of two world wars demonstrated that American security and economic interests were inseparable from global stability.

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

Legally binding treaty. It covers many of the rights under the UDHR.

Civil and political rights

Right to life: Everyone has the right to life, liberty, and security of person.

Freedom from discrimination: Everyone is entitled to the rights in the covenant without distinction of any kind, such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.

Equality: Men and women have equal rights to enjoy all civil and political rights.

Freedom of movement: Every individual has the right to liberty of movement and freedom to choose their residence within their territory.

Freedom of thought, conscience, and religion: Individuals have the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion.

Freedom of expression: Everyone has the right to freedom of expression.

Right to a fair trial and due process: The covenant includes provisions for the right to a fair trial, freedom from torture, and protection against arbitrary arrest or detention.

Right to liberty and security: Individuals have the right to liberty and security of person.

ICCPR Limitations

Two main limitations:

Public emergencies, “which threatens the life of the nation and the existence of which is officially proclaimed,”(Article 4) permits derogation.

Limitation clauses: allowing some restrictions that are ”necessary in a democratic society” for the purpose of public order or morals.

ICCPR Origins

Liberal theories of freedom: Rooted in Enlightenment philosophy (Locke, Montesquieu, Rousseau).

• Emphasis on individual liberty, limits on state power, rule of law, and representative institutions.

• Rights framed as negative freedoms — protection from interference (e.g., freedom of speech, religion, assembly).

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)

Covers economic, social, and cultural rights.

Purpose: To promote and protect economic, social, and cultural

rights; complements the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

• State obligations: States must take steps, to the maximum of

their available resources, to progressively achieve full realization

of rights.

Self-determination: Guarantees the right of all peoples to freely pursue their political, economic, social, and cultural development.

Right to work: Includes the right to work, fair and safe working conditions, equal pay for equal work, and the right to form trade unions.

Right to an adequate standard of living: Covers the right to sufficient food, clothing, and housing.

Right to health: Guarantees the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.

Right to education: Includes the right to education at all levels and the promotion of free and compulsory primary education.

Right to social security: Commits states to providing social security.

Equality: Ensures the equal right of men and women to enjoy all the rights in the covenant without discrimination.

ICESCR Origins

• Religious teachings about protecting the poor and the vulnerable.

• Political theories, especially socialist theories.

• These rights were divisive during the Cold War, and social and economic rights were promoted by the Second World (the

Socialist bloc).

• The US signed but has not ratified the ICESCR

Can civil and political rights be fully realized without economic, social, and, cultural rights?

No, civil and political rights cannot be fully realized without economic, social, and cultural rights because all human rights are interdependent and indivisible. For example, the ability to participate in politics is hindered by a lack of education, and freedom of expression is limited when basic needs like food and shelter are not met.

US Opposition to ICESCR

US has been visibly opposing economic, social, and cultural rights

• Truman Administration was supportive and until Carter Administration they there mostly agnostic.

• Carter Administration signed it and wanted to ratify it; but this was reversed by Reagan and Bush Administrations.

• Clinton Administration signaled that they would work towards its ratification, but did not do so.

• Obama administration announced a policy shift in 2011.

EX: Did not agree with Right to water

“United States is not a party to the ICESCR, and the rights contained therein are not justiciable in U.S. courts. We disagree with any assertion that the right to safe drinking water and sanitation is inextricably related to or otherwise essential to enjoyment of

other human rights, such as the right to life [under the ICCPR]. To the extent that

access to safe drinking water and sanitation is derived from the right to an adequate standard of living, it is addressed under the ICESCR, which imposes a different standard of implementation than that contained in the ICCPR”

Indivisibility after the Cold War

The bridge between the ICCPR and the ICESCR

• The 1993 Vienna World Conference on Human Rights famously concluded that: ”All human rights are universal, indivisible and

interdependent and interrelated. The international community must treat human rights globally in a fair and equal manner, on the same footing, and with the same emphasis.

Nuremberg Trials (1946)

Nuremberg was a Military Tribunal to judge military and political leaders who had committed war crimes during WWII.

• On November 20 1945, 21 defendants appeared in court.

• Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler, and Joseph Goebbels could not be tried because they committed suicide at the end of the war or

soon afterwards. Hermann Göring was the highest-ranking Nazi official among the defendants.

• On October 1, 1946, the Tribunal convicted 19 of the defendants and acquitted three. Of those convicted, 12 were sentenced to

death.

Subject of international law: States

There wasn’t a tradition of establishing individual criminal responsibility until Nuremberg decision for relations among nations; only states are liable.

Sovereign immunity

Before Nuremberg Heads of states would be immune from international criminal prosecutions

• Applying individual criminal responsibility to the head of states and high-ranking officials was not something done before.

The problem of retroactivity

nullum crimen sine lege (No crime

without law) and nulla poena sine lege (No punishment without law)

Voluntarist (positivist) international law

laws are created and accepted

by states.

Natural law

laws exist outside of states – some wrongs are wrong even though they might not be covered by laws at the time

Middle-ground

The Nuremberg Tribunal argued it was not creating new law but rather articulating and enforcing principles already implicit in international agreements, state practice, and conscience of humanity.

Tokyo Trials

a series of international military tribunals held from 1946 to 1948 to prosecute leaders of the Japanese Empire for war crimes committed during World War II. They charged 28 high-ranking Japanese officials with crimes against peace, conventional war crimes, and crimes against humanity, resulting in the conviction and sentencing of most defendants, including seven death sentences for crimes against peace and humanity. These trials established a precedent for international criminal law, though they have also faced criticism, including for excluding Emperor Hirohito and being perceived by some as a "victor's justice"

Weiss et al. 2020 - Human rights and adjacent

fields

• Since 1945, states have used their constitutive powers to create institutions that would restrict their own sovereignty.

• Human rights: codified entitlements (civil, political, social, economic)

• International humanitarian law: protections during armed conflict (e.g., Geneva Conventions)

• Humanitarian action: relief regardless of rights language (e.g.,natural disasters, refugee aid)

• In practice, often overlapping

Why states follow human rights sometimes/not?

According to Weiss, domestic institutions and politics significantly influence a state's compliance with human rights treaties

The United States provides a concrete example, with its federal system, lack of a national human rights institution, and separation of powers creating barriers to fully implementing the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, leading to repeated non-compliance findings by the UN Human Rights Committee on issues like the criminal justice system and voter suppression.

Strategic calculation

Domestic politics

Reputational costs

International humanitarian law (IHL)

Sometimes called the laws of war or humanitarian law

• Regulates the conduct of armed conflict and protects those not

participating in hostilities as well as those who do not participate

(e.g., civilians, humanitarian workers, healthcare professionals)

• Goal: limit suffering in war

• Universal Ratification: Geneva Conventions signed by all states

• International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC): guardian of IHL

– created by Swiss businessman Henry Dunant

1864 Geneva Convention (early IHL work)

protection for wounded soldiers

Hague Conventions (1899, 1907)

rules on warfare conduct

1949 Geneva Conventions

cornerstone of modern IHL

Protection of wounded/sick (land & sea)

Prisoners of war (POWs)

1977 Protocols I & II

• Expanded protection for civilians, children, and women

• Recognition of wars of national liberation as international conflicts

• Rules for non-international armed conflicts, outlining protections

such as humane treatment for detainees and prohibitions against

terrorism, murder, and pillage

Core norms in the UN era

UN Charter (1945): vague but foundational references to rights

(Articles 1, 55, 56)

• Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948): 30 rights, 3

“generations”

1.Civil & political (negative rights)

2.Economic, social, cultural (positive rights)

3.Collective/solidarity (self-determination, development, environment)

Hierarchy of Norms

Some view that there is hierarchy with jus cogens at the top

Fundamental norms of international law that cannot be

suspended or displaced (no derogation is allowed).

• International Law Commission (ILC) definition: “[Jus cogens

norms] reflect and protect fundamental values of the international

community, are hierarchically superior to other rules of

international law and are universally applicable.”

ILC list of peremptory norms

• The prohibition of aggression

• The prohibition of genocide

• The prohibition of crimes against humanity

• The basic rules of international humanitarian law

• The prohibition of racial discrimination and apartheid

• The prohibition of slavery

• The prohibition of torture

• The right of self-determination

Habré Timeline

1982: Hissène Habré becomes leader of

Chad. Widespread atrocities.1990: Habré deposed (with a coup) by

Idriss Dèby and receives asylum in

SenegalHabré victims seek justice in Chad,

Senegal, Belgium, ...2016: Habré found guilty of crimes in a

special international tribunal

(Extraordinary African Chambers)

How did U.S. & France act towards Habré

Both states helped Habré gain power and survive in office

Complicity not a general mode of responsibility under IL

Prosecute or extradite

Concerns violation of a jus cogens norm: prohibition of torture

protected under the UN Convention Against Torture (CAT).

According to CAT: either prosecute the perpetrator or extradite him (aut

dedere aut judicare).

Belgium attempted to extradite Habré, whereas the African Union

insisted Senegal should try Habré on behalf of Africa

But the crimes concerned did not take place in Belgium and did

not involve Belgian nations.

Belgium’s Position

Claim: Belgium has no jurisdiction.

• Belgium claimed to have “legal interest” in this case since it is a

violation of jus cogens norm and it generates erga omnes partes

obligations (common interest for justice).

• Belgium: invoked universal jurisdiction

• Most straightforward source of jurisdiction is territory (acts that are

committed within borders of a state) or active personality (acts that are

committed by a national but outside of that state’s territory.

• Universal jurisdiction: Use of a state’s domestic law and institutions to

regulate behavior that occurs outside of its domestic territory, does not

involve its nationals.

Senegal’s position

• Claim: Senegal has treaty obligations under Convention Against Torture because Habré was on its territory.

• What is Senegal’s argument?

• It took the necessary steps:

• Tried to try him at home and initiated constitutional and legislative

reforms in 2007.

• But Senegalese courts refused to try him claiming they lacked

jurisdiction.

• ECOWAS court said Senegal cannot retroactively apply universal jurisdiction before 2007 and recommended the creation of an ad hoc international proceeding.

• The African Union said Senegal should try Habré on behalf of Africa.

Senegal breached its obligations and did not do everything within its powers to try Habré.

• Habré was eventually prosecuted by the Extraordinary African Chambers – a special tribunal created by the African Union.

Makau Mutua,“Savages, Victims, and Saviors” (2001)

Argument: Human rights narrative rests on a damning metaphor Savages Victims and Saviors (SVS)

• Savages → violators of human rights (often states, cultures, practices coded as “non-Western”).

• Victims → helpless, powerless individuals stripped of dignity.

• Saviors → Western states, INGOs, UN, international law.

Whats Mutua’s critique of human rights project?

• Human rights = Eurocentric project tied to colonial history.

• Replicates binaries: civilized/barbaric, modern/traditional,West/non-West.

• Creates a hierarchy: saviours (white, Western) vs. victims/savages (non-Western, racialized).

Problems with SVS narrative

• Universality undermined → ignores the marginalized communities’ anti-slavery or anti-colonial struggles, and non-Western traditions of rights in general.

• Othering: non-Western cultures forced to mimic Western prototypes.

• Racial undertones: savages/victims = non-white; saviours = white.

Path forward from SVS?

• Need for a multicultural, inclusive, deeply political human rights discourse.

• Must reject the SVS metaphor and Eurocentrism.

• Start from moral equivalency of all cultures.

What do we do when addressing practices like female genital

mutilation?

Recognized internationally as a violation of human rights but practiced in

various cultural contexts, often justified through tradition, purity, or social

acceptance.

Engage influential community members/education: Work with religious leaders, elders, and respected women to challenge and shift the social norms that sustain FGM. Involving these leaders helps build trust and acceptance for new ideas.

Facilitate open discussion: Create safe spaces for community dialogues and education to raise awareness about the risks of FGM. The UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme works to shift social norms by fostering these community-led conversations.

Use culturally sensitive methods: Programs can use traditional and community-accepted forms of communication, such as theater, songs, and games, to educate families on the harms of FGM.

Advance girls' education: Research shows that girls with higher levels of education are significantly more likely to oppose FGM. Education provides girls with new perspectives and the confidence to challenge harmful traditions.

Strengthen economic independence: Offer programs that reduce a family's reliance on FGM as a prerequisite for marriage and financial security. Cash transfers, for example, have been successful in addressing the poverty that can drive families toward such practices.

Offer comprehensive medical care: Train healthcare providers to address FGM-related complications with competence and empathy. This includes managing immediate risks like bleeding and infection, as well as long-term issues like chronic pain, infertility, and complications during childbirth.

Ratna Kapur, “Liberal Freedom in a Fishbowl”

• Central metaphor: the fishbowl → how liberal freedom, at the core of human rights, is framed, regulated, and limited.

• “Fishbowl” = bounded, confined vision of freedom.

What’s Kapur’s argument?

• Key concern: “freedom” under liberalism often produces unfreedom.

• Assumption: more rights → more freedom.

• BUT: this is not the case for many marginalized people.

• Human rights discourse produces hierarchies of subjects → who counts, who doesn’t.

Concept of Freedom & unfreedom

• Liberal freedom tied to histories of colonialism, racial supremacy, gender hierarchies.

• Human rights = not neutral → It functions as a regulatory apparatus tied to markets, colonial inheritances, and exclusions.

How so?

• Solution: freedom in unliberal (not illiberal) spaces

• Non-western, religious, unsecular spaces

Teacher Headscarf (Germany, 2003)

• Muslim woman denied teaching job for refusing to remove headscarf

• Government: headscarf = cultural/political symbol, not compatible with state neutrality

• Court: blanket ban violates religious freedom & equal access to public office

• Outcome: Restrictions need clear legal basis & justification

Şahin v. Turkey (ECtHR, 2005)

• Following a government decree, Istanbul University banned students from wearing headscarves/beards

• Applicant suspended, had to leave studies

• Court: secularism is a legitimate aim under Article 9 ECHR (Freedom of thought, belief and religion)

• Outcome: No violation: states have a margin of appreciation in regulating religion in education

• Margin of appreciation: leeway that states enjoy when it comes to implementing human rights protections

• Headscarf ban reversed in 2013

Muslim headscarf case background

• International law protects both:

• Freedom of religion and belief

• Freedom to manifest religion (worship, observance, practice,

teaching)

• BUT: manifestation can be limited for public safety, order, health,

morals, or rights of others

• Key tension: religious freedom vs. secularism, equality, and

neutrality

Margin of appreciation

leeway that states enjoy when it comes to implementing human rights protections

John T. Baker (1965), Human Rights in South Africa

• Written during apartheid’s height; author treats apartheid as a violation of international law.

• Frames South Africa’s racial regime as an affront to the “community of nations.”

• Notice not civilized nations

• Argues that international intervention, through the UN or collective action, is necessary to prevent escalation into race war.

Apartheid Historical background

From European settlement (1652) to 20th-century segregation, racial domination was systemic.

• Apartheid system began in 1948

• 1960 population: 3 million Whites vs 13 million non-Whites.

South Africa imposed apartheid categories

• White: People of European descent (mainly Afrikaner and English).

• Enjoyed full political rights, land ownership, and economic privileges.

• Bantu / African: Indigenous peoples of South Africa.

• Subjected to pass laws, denied voting rights, and forcibly relocated to Bantustans.

• Coloured: People of mixed racial ancestry (European, African, Malay, or others).

• Occupied an intermediate social position; they had some urban privileges, but denied political rights.

• Asian / Indian: Descendants of indentured laborers and traders from India.

• Faced residential and occupational segregation; excluded from “white”

institutions.

Apartheid legislation and international norms

• Contrasts apartheid laws with the Universal Declaration of Human

Rights (1948).

Highlights discriminatory acts:

• The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act (1949) and the Immorality Amendment Act (1950) – no marriages or sexual relationships between black and white populations.

• Population Registration Act (1950) – rigid racial classification.

• Reservation of Separate Amenities Act (1953) – legalized “separate, not necessarily equal.”

• Suppression of Communism Act (1950) – used to silence dissent.

• Pass Laws – restricted Black mobility and employment.

Resistances to Apartheid

• 1950 – mass civil disobedience campaigns.

• A Coalition of anti-apartheid groups: African National Congress (ANC) South African Indian Congress (SAIC) and South African Communist Party (SACP) issued the Freedom Charter (1955) – a visionary call for “A non-racial, democratic South Africa”.

• 1960 - the Sharpeville Massacre - peaceful anti-pass protest in Sharpeville met with lethal force and 72 people died.

• 1970s – the Black Consciousness Movement and Soweto Uprising

• 1980s – mass mobilization and international pressure.

• 1990-1994 – Apartheid finally ends.

What rights were people deprived of under apartheid?

• Civil and political: denial of franchise, segregation, arbitrary detention.

• Economic and social: restrictions on land, education, housing, labor.

• Everyday humiliation: separate entrances, benches, schools, even court witness boxes.

Baker’s legal reasoning

• Apartheid violates:

• Universal Declaration (Articles 1–11, 13, 23)

• UN Charter (Preamble, Article 55)

• Argues that systematic racial discrimination removes the issue from “domestic jurisdiction.”

• Calls for UN-led collective action to uphold human rights and a global action

Audrey R. Chapman (2007), Truth Commissions and Intergroup Forgiveness

• Asks - Can truth commissions foster intergroup forgiveness and reconciliation in post-conflict societies?

• Case: South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC),

established 1995.

• Six-year empirical project. Sources: 1,819 TRC victim-hearing

transcripts + focus-group interviews.

Chapman’s findings?

Forgiveness rare: only 14 % of deponents mentioned it; fewer

than 2 % offered unconditional forgiveness.

• Conditional forgiveness: most required truth, apology,

compensation, or meeting the perpetrator.

• Reconciliation seldom invoked: 11 % referenced it, often when

prompted.

• Perpetrator side: little acknowledgment, remorse, or restitution.

TRC Interpretation

• TRC equated reconciliation with interpersonal forgiveness,

neglecting intergroup or structural dimensions.

• Dominant Christian moral framing (Archbishop Tutu) shaped

expectations.

• Victims prioritized truth and justice over forgiveness.

• Education and religious discourse slightly correlated with

willingness to discuss forgiveness.

TRC Critiques

• TRC’s mandate: “promote national unity and reconciliation.”

• Forgiveness cannot substitute for structural transformation or social justice.

• Risk: symbolic “rituals” of forgiveness overshadow material reparations.

• Is forgiveness necessary for reconciliation? Can there be forgiveness without justice?

• Forgiveness often refers to personal or interpersonal healing (a moral or emotional act by victims).

• Reconciliation is social and political (rebuilding relationships, institutions, and trust within a divided society).

Desmond Tutu, Foreword to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report (1998)

• Context: Post-apartheid South Africa, after Nelson Mandela’s inauguration

• Purpose: To reflect on South Africa’s moral, political, and emotional transition

• Core themes: truth, forgiveness, justice, reconciliation

• Aim: national healing through truth-telling rather than vengeance.

• The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) chaired by Archbishop Desmond Tutu

Desmond Tutu’s Transitional Options

• Option 1: Prosecutions (Nuremberg model) → Impossible in context.

• Option 2: Forget the past (“let bygones be bygones”) → Re-traumatizes victims.

• Option 3: Truth and reconciliation → Grounded in Ubuntu: our shared humanity; a need for understanding but not for vengeance.

→ Truth-telling as justice and healing.

→ The right to truth – individuals and public in general has a right to know the

truth about the circumstances surrounding large scale violent acts

Why not Nuremberg instead of TRC?

• No victor’s justice: apartheid ended in negotiated settlement, not military defeat.

• Trials would risk civil war and exhaust judicial resources.

• Instead: amnesty for truth —“Freedom was granted in exchange for truth.”

• Tutu’s appeal: white South Africans should confess and ask forgiveness “without qualification.”

• Magnanimity of victims as a moral example.

• Healing requires mutual recognition of suffering.