APUSH Period 6

1/205

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

206 Terms

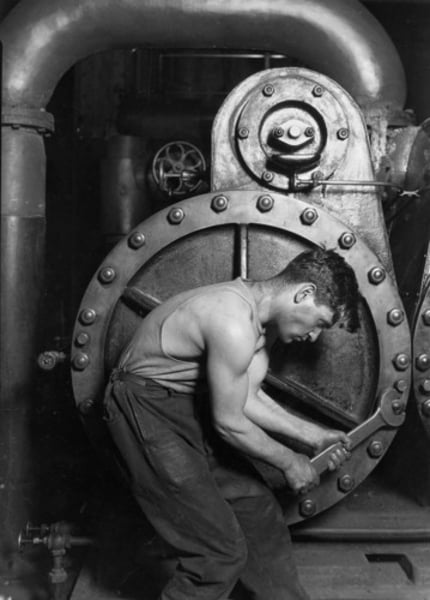

The Second Industrial Revolution

A rapid and profound economic revolution lastly roughly from the end of the Civil War into the early twentieth century. The period was characterized by industrialization, urbanization, immigration, increasing reliance on fossil fuels, and enormous economic productivity and output. It had numerous causes, including abundant natural resources, a growing supply of labor, an expanding market for manufactured goods, the availability of capital for investment, and a federal government that actively promoted economic and agricultural development ("pro-big business laissez faire").

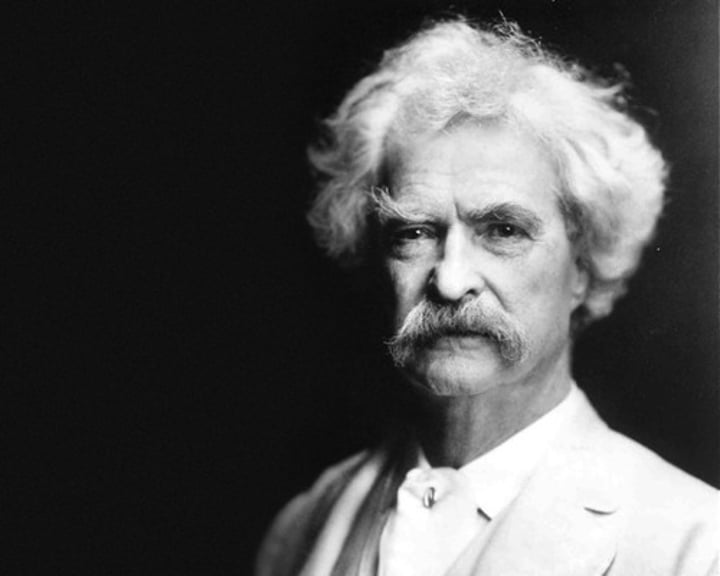

The "Gilded Age"

A title of a Mark Twain novel from the 1870s, this pejorative term has been adopted by historians as a name for the last few decades of the 19th century. As opposed to a "golden age," "gilded" means covered with a layer of gold. The name suggests that beneath the impressive economic growth and innovation of the Second Industrial Revolution, there was also corruption and oppressive treatment of those left behind in the scramble for opportunity and wealth.

Urbanization

A large shift of the American population from rural to urban areas during the Second Industrial Revolution. Between 1870 and 1920, almost 11 million Americans moved from farm to city.

The national railroad system

This transportation system made the Second Industrial Revolution possible. It was spurred by private investment and massive grants of land and money by federal, state, and local governments (and example of PBBLF), and the miles of track in the U.S. exploded between the Civil War and 1920, becoming the largest railroad system in the world at the time, opening up vast new areas for commercial farming and creating a national market for manufactured goods. This transportation system reorganized time itself; in 1883, the major companies divided the nation into four time zones still in use today.

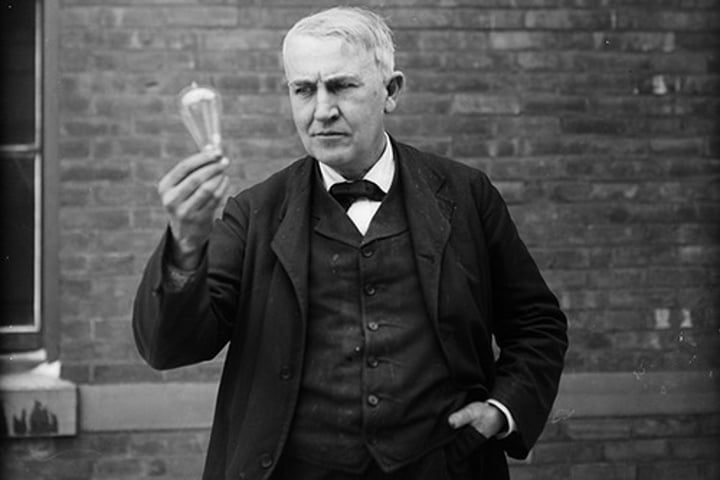

Thomas Edison, "The Wizard of Menlo Park"

Widely considered the greatest inventor of the Second Industrial Revolution, this person and his team of researchers at his laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey developed inventions that transformed private life, public entertainment, and economic activity, including the phonograph, light bulb, motion picture, and a system for generating electric power.

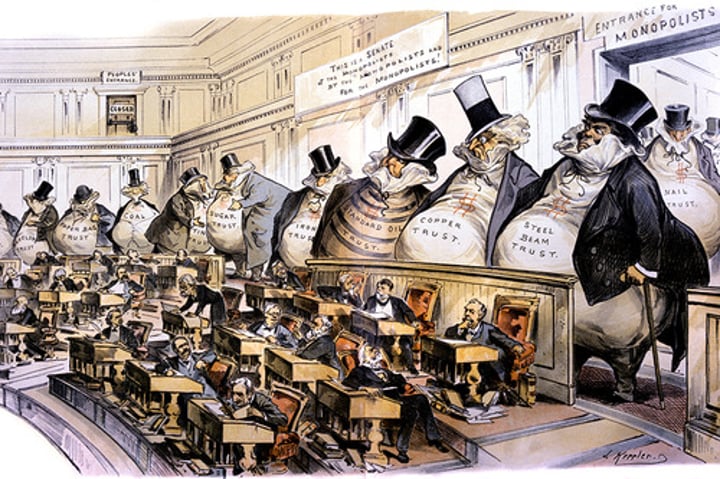

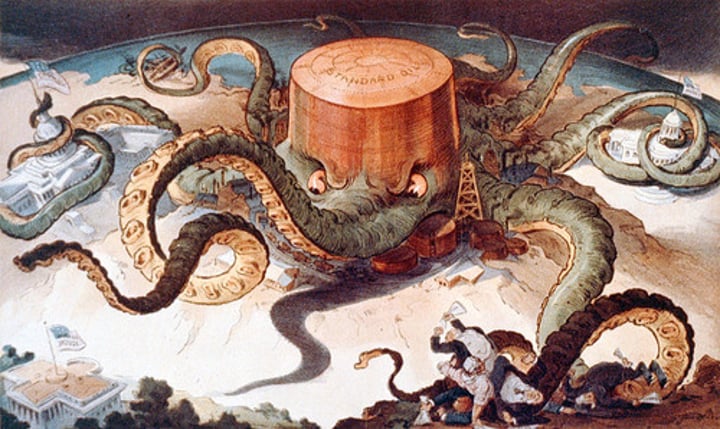

Trusts

These were legal devices whereby the affairs of several rival companies were managed by a single director in order to limit competition between them. They developed during the Second Industrial Revolution as companies tried to bring order to the chaotic marketplace. These were enabled by PBBLF and they are illegal today.

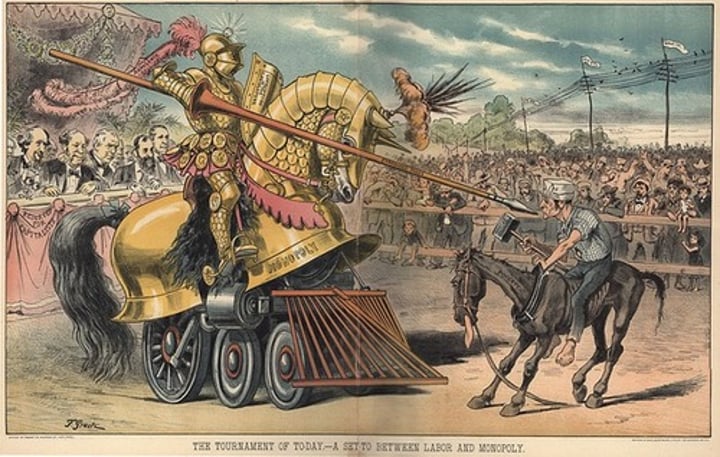

Monopolies

These often developed during the Second Industrial Revolution through cutthroat competition when one company came to dominate an entire industry, which resulted in limited competition and higher prices for consumers. These were enabled by PBBLF and they are illegal today.

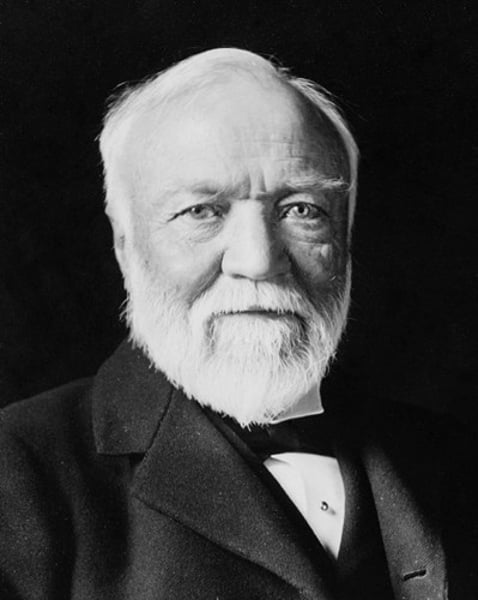

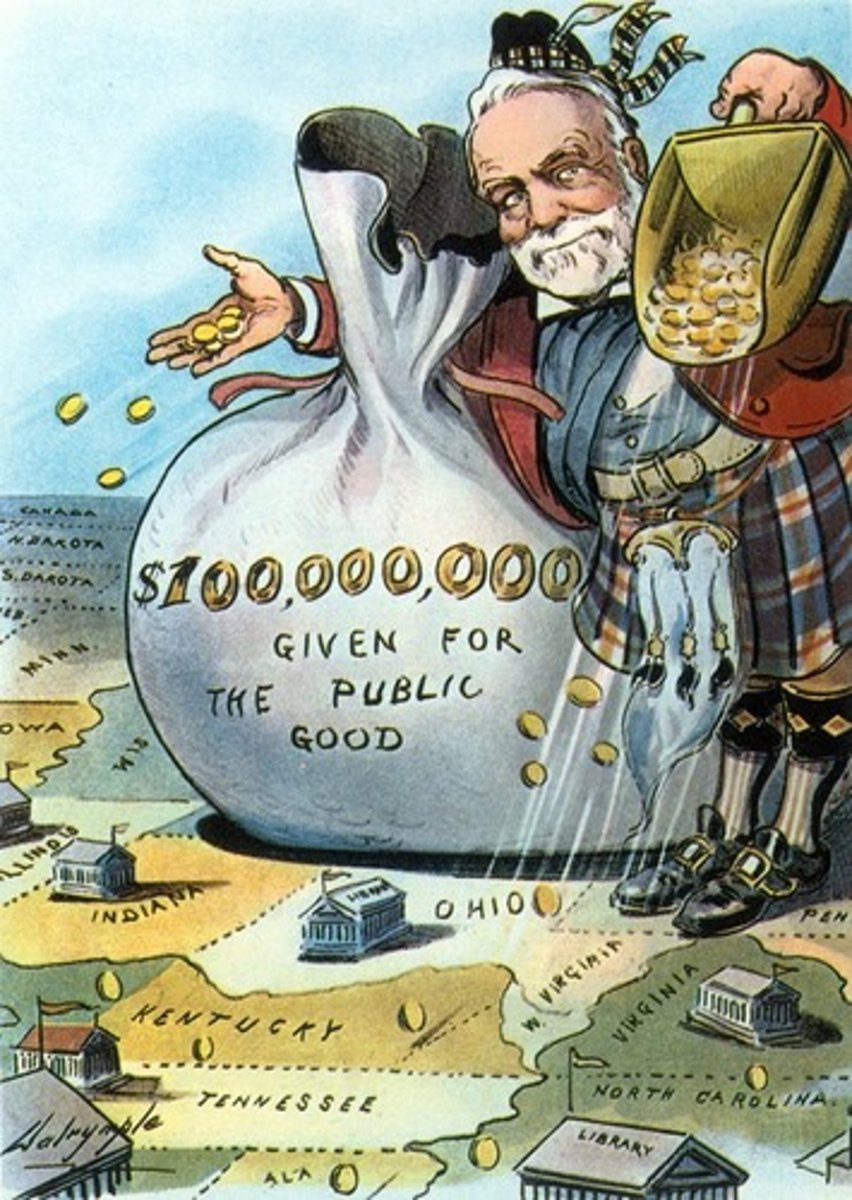

Andrew Carnegie

In the quintessential "rags to riches" story, this Scottish Immigrant came to the U.S. as a boy and worked his way up to become one of the richest men in the world. He built a Steel Company in his name through "vertical integration"--that is, controlling every phase of the business from raw materials to transportation, manufacturing, and distribution. His steel factories at Homestead (the site of a major labor battle during the Gilded Age) were the most technologically advanced in the world. He opposed unionization for his employees but promoted philanthropy with his "Gospel of Wealth."

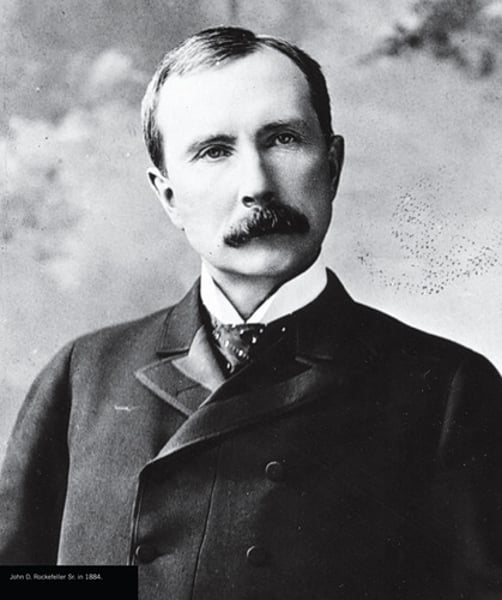

John D. Rockefeller

The leading figure in the U.S. oil industry and one of the richest people in the world, he used "horizontal integration" (buying up all his competitors) and later "vertical integration" (controlling the drilling, refining, storage, and distribution of oil) to build his company, Standard Oil, which controlled ninety percent of the nation's oil industry. Like Carnegie, he fought unionization but gave much of his fortune away, establishing foundations to promote education and medical research.

"captains of industry" or "robber barons"

Two terms that refer to the opposing viewpoints that industrial leaders were either beneficial for the economy or wielded power without any accountability in an unregulated market.

Social Darwinism

A popular Gilded Age concept that celebrated the "survival of the fittest" to justify class distinctions and to explain poverty. In their misapplication of Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection to society, proponents believed that some people were more "fit" than others, and this inequality in individual fitness explained the maldistribution in wealth in modern capitalist societies and helped to justify PBBLF policies. For government or private individuals to assist the poor would be to interfere in a natural process by which the unfit are weeded out so that society could progress.

William Graham Sumner's What Social Classes Owe Each Other, 1883

A classic book promoting the philosophy of social darwinism. According to its author, "A drunk in the gutter is exactly where he ought to be."

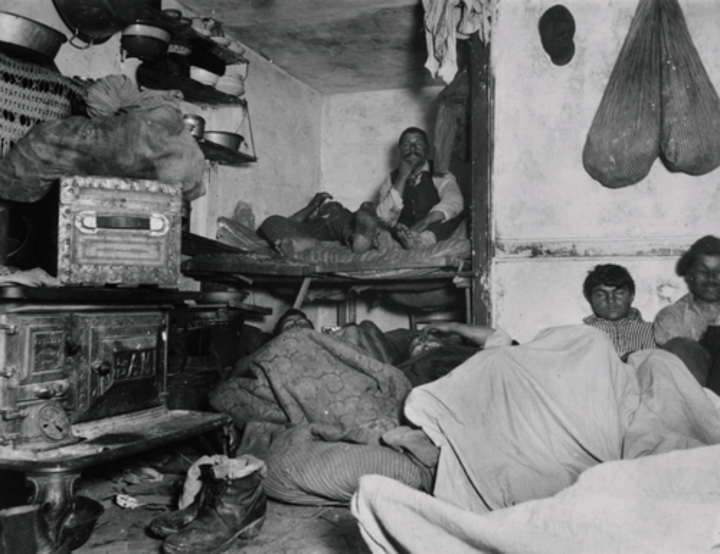

Jacob Riis' How the Other Half Lives (1890)

A book that offered a shocking account of living conditions among the urban poor, complete with photographs of apartments in dark, airless, overcrowded tenement houses. This book became a classic example of "muckraking" in the Gilded Age.

Frederick Jackson Turner's "Frontier Thesis"

This (University of Wisconsin) historian's 1893 essay argued that the western frontier process had forged the distinctive qualities of American character (individualism) and government (political democracy). He portrayed the West as an empty space ("free land") before the coming of white settlers, for this reason and others, his argument has been widely rejected by modern historians. With the "closing" of the frontier, according to the 1890 U.S. census, foreign policy planners used this essay to justify imperialism abroad because, they believe, continuous expansion was what sustained America's ruggedly individualistic and democratic institutions.

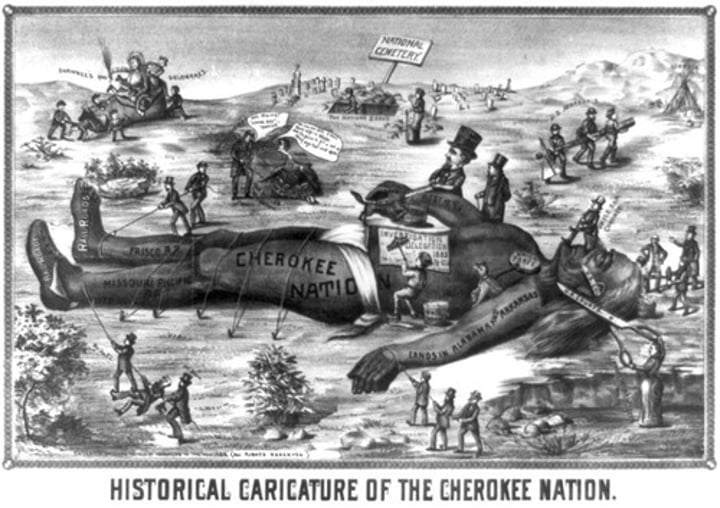

The Subjugation of the Plains Indians

As white settlers flooded onto the Great Plains in the Gilded Age, they came into conflict with the native populations. A series of dramatic battles and massacres occurred (including the Sand Creek Massacre in 1964, the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, and the Nez Perce War in 1877), often between Native peoples trying to continue their traditional ways of life and U.S. soldiers with orders to remove them onto reservation lands.

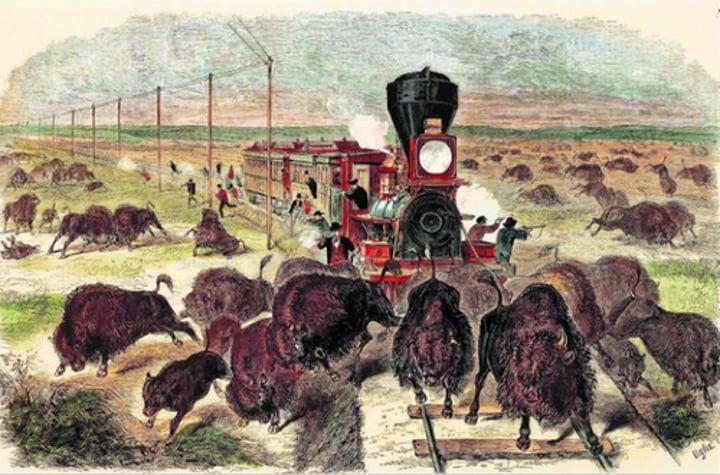

Destruction of the Buffalo

For the past several hundred years, Indians on the Great Plains had developed a whole cultural, spiritual, and economic way of life that was centered on the enormous buffalo herds that used to graze on the Great Plans. As railroad and wagon trains brought settlers onto the Plains, hunters seeking buffalo hides brought the vast herds to the brink of extinction. The wars of the late 19th century on the Great Plains were often fought by starving Indians.

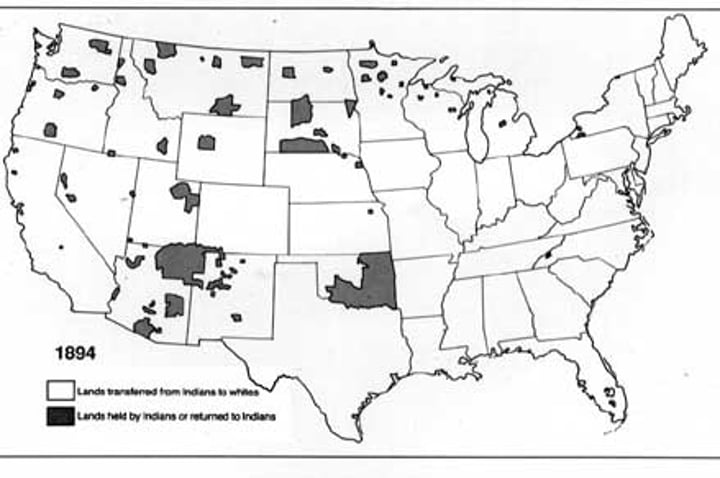

The Indian Reservation system

In the late 1800s, the federal government set aside areas of land in the West and forced Indian nations to relocate onto them or else face the U.S. military. These tended to be on lands that were the least desirable to white settlers (usually unsuitable for farming or resource extraction), and they represented only a tiny fraction of Western land that Indian nations controlled a century prior.

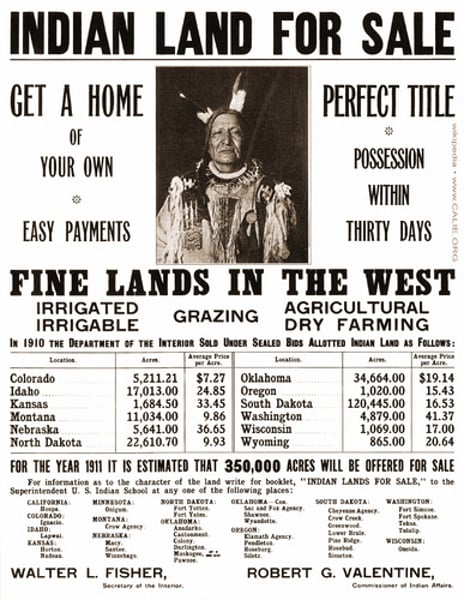

The Dawes Act, 1887

Law passed in 1887 meant to encourage adoption of white norms among Indians; it broke up tribal holdings (reservations) into small farms for Indian families, with the remainder sold to white purchasers. The policy proved to be a disaster, leading to the loss of much tribal land and the erosion of Indian cultural traditions. As cruel is this policy may seem from our perspective today, it was actually a policy favored by the progressives of the era who believed Native Americans could assimilate into life within the United States, and it was seen as a more humane alternative to the outright elimination and genocide of indigenous peoples advocated by some ethnic nationalists.

Carlisle Indian School

One of the boarding schools established by the Bureau of Indian Affairs where Indian children were taken to be stripped of the "negative" influence of their parents and tribes, dressed in non-Indian clothes, given new names, and educated in white ways (Christianity, English, and trade skills). With the motto of "Kill the Indian; Save the Man," the school forcibly assimilated Indian children to life in the U.S.. Critics today consider this an example of "cultural genocide."

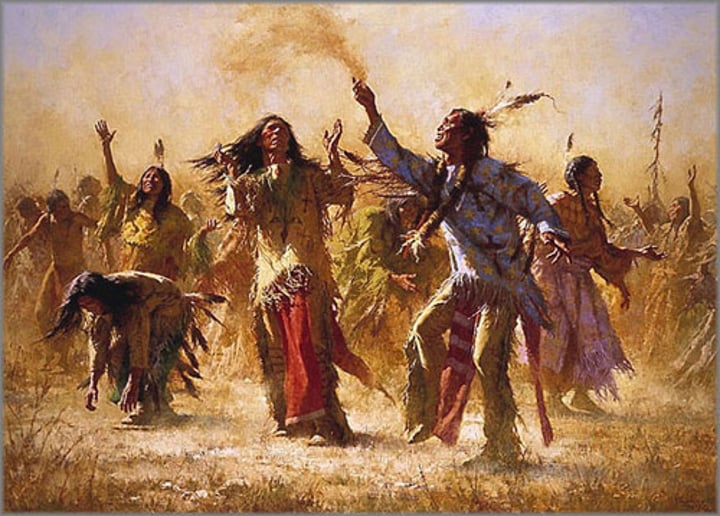

The Ghost Dance (1889-91)

A pan-Indian religious revitalization movement that sweep through Native American communities in the late 19th century, reminiscent of the pan-Indian movements lead by earlier prophets; leaders foretold a day when whites would disappear, the buffalo would return, and Indians could once again practice their ancestral customs. Seen by whites as a dangerous form of native resistance to U.S. settlement, this movement was attacked and destroyed militarily by the U.S. government.

Wounded Knee Massacre, 1890

In 1890, U.S. soldiers opened fire on Ghost Dancers at this locations in South Dakota, killing between 150 and 200 Indians, mostly women and children. This horrific event marked the end of four centuries of armed conflict between the continent's native population and European settlers and their descendants. Estimated to be well over several million on the eve of contact in 1492, the Indian population within the United States had fallen to 250,000 by the 1900 census.

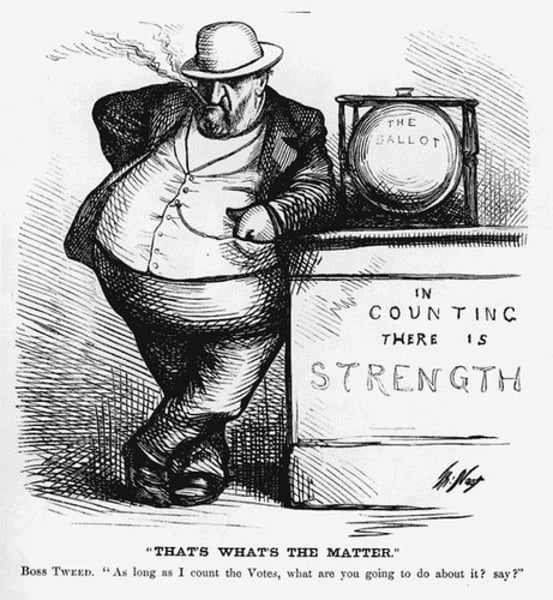

New York's "Boss" Tweed Ring

This corrupt urban political machine reached into every New York City neighborhood and won support from the city's immigrant poor by fashioning a kind of private welfare system that provided food, fuel, and jobs in hard times while also plundering the city of tens of millions of dollars. It illustrates the kind of political corruption that Progressive reformers would try to eliminate a generation later.

Crédit Mobilier Scandal, 1867

The most notorious example of corruption in federal politics during the Gilded Age in which lawmakers supported bills aiding companies in which they had invested money or from which they received stock or salaries. This scandal is named after a construction company that charged the (government-assisted) Union-Pacific Railroad exorbitant rates to build the eastern half of the first transcontinental railroad line, then they paid the lawmakers to look the other way.

Liberty of Contract

The freedom for workers to negotiate the substance of their contract with their employers. In reality, given how much more powerful large employers were than their relatively interchangeable workers, this liberty was far more advantageous to employers than to workers. Nevertheless, for several decades, the Supreme Court used this theory to reconcile freedom and authority in the workplace.

Pro-big business laissez faire (PBBLF)

This is the term historians use to describe the role of the national government in the economy during Gilded Age. The government was actively involved in the economy in ways that promoted big business (subsidizing railroads, canals, roads; putting down labor strikes, forcing Native Americans onto reservations, subsidizing mail; maintaining protective tariffs; subsidizing research and development; surveying Western lands and giving it to settlers; pursuing an imperialistic foreign policy for natural resources and markets, attracting immigrant labor, etc.). But the government was very limited, or "hands-off," in its efforts to protect the interests of workers, consumers, or the environment.

Wabash v. Illinois, 1886

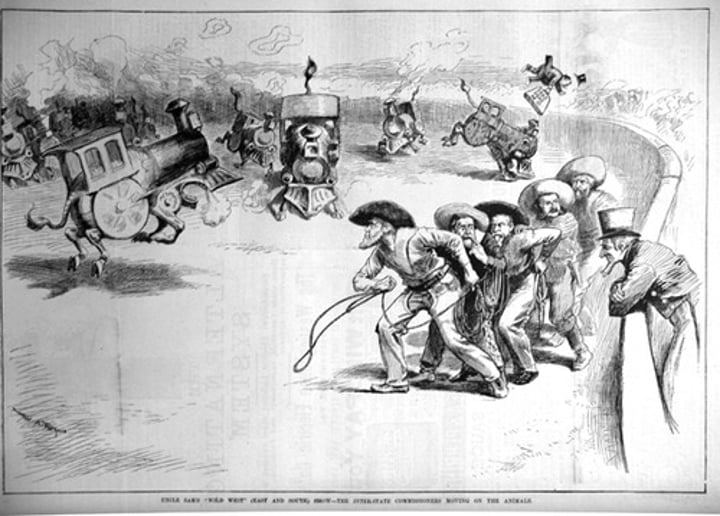

In this decision, the Supreme Court struck down an Illinois law that regulated railroads by ruling that only the federal government, not the states, could regulate railroads engaged in interstate commerce. Thus, this was a pro-big business Supreme Court ruling. This angered many people (especially western farmers) who thought that railroad rates needed to be regulated in the interest of the public good, and thus Congress responded the next year by passing the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887.

Interstate Commerce Commission, 1887

Reacting to the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Wabash Railroad v. Illinois (1886), Congress established this commission in an effort to limit the abuses in the railroad industry. However, this commission lacked the power to establish railroad rates on its own; all it could do was sue railroad companies in court, and thus its overall effect was minimal (reflecting PBBLF). Three years later, Congress followed this up with the Sherman Anti-Trush Act.

Sherman Anti-Trust Act, 1890

This was the first federal law to restrict monopolies and trusts. Unfortunately, the language was so vague that the law proved nearly impossible to enforce (thus reflecting PBBLF). Nevertheless, it established the precedent that the federal government could regulate the economy to promote the public good, and it was later strengthened during the Progressive Era by the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914

Lochner v. New York, 1905

The Supreme Court, in this case, voided a state law establishing ten hours per day, or sixty per week, as the maximum hour of work for bakers. The New York Law, wrote one justice, "interfered with the right of contract between employer and employee." This notorious ruling gave the name "Lochnerism" to the entire body of liberty of contract decisions. It reflected the PBBLF ideas of the era.

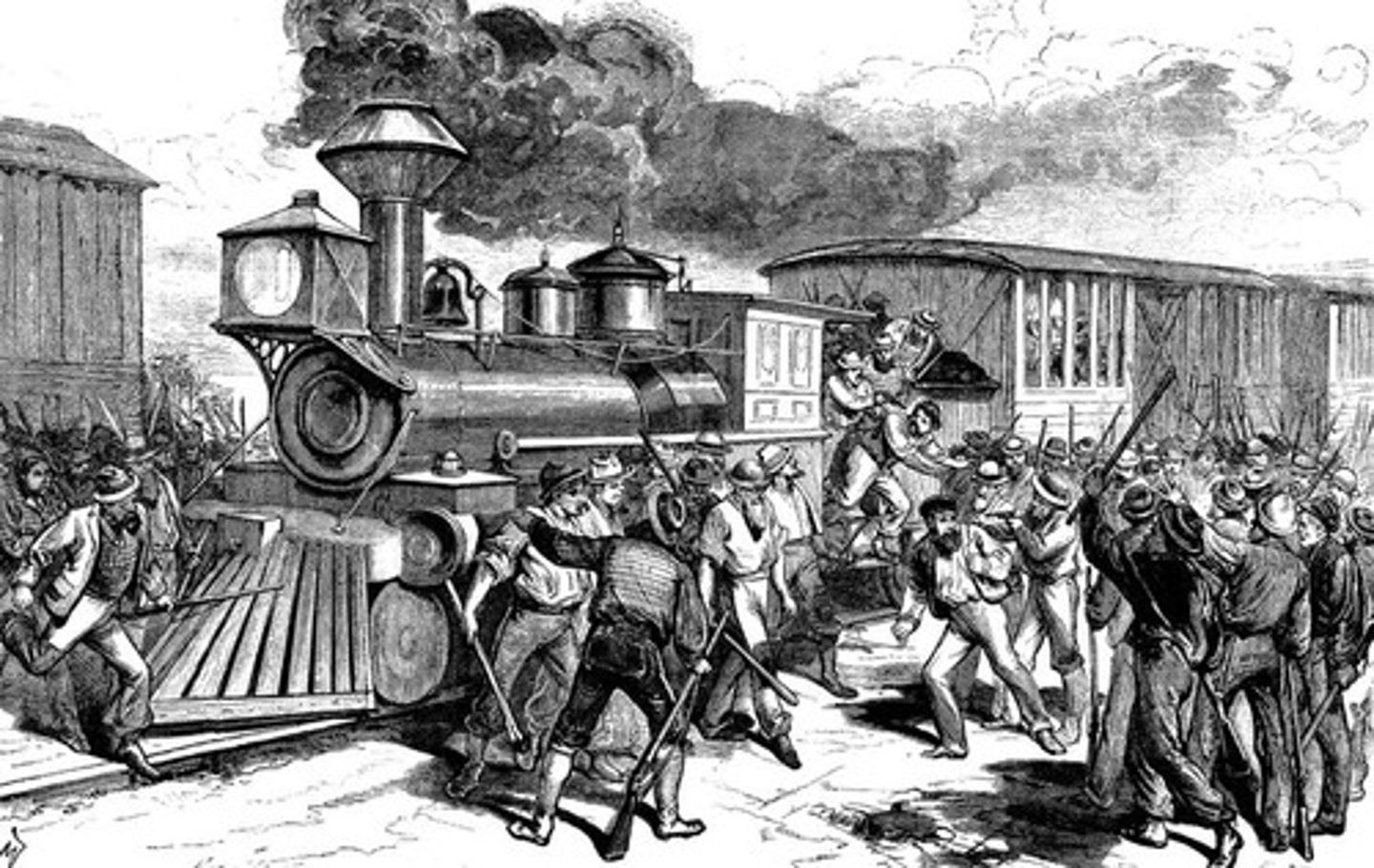

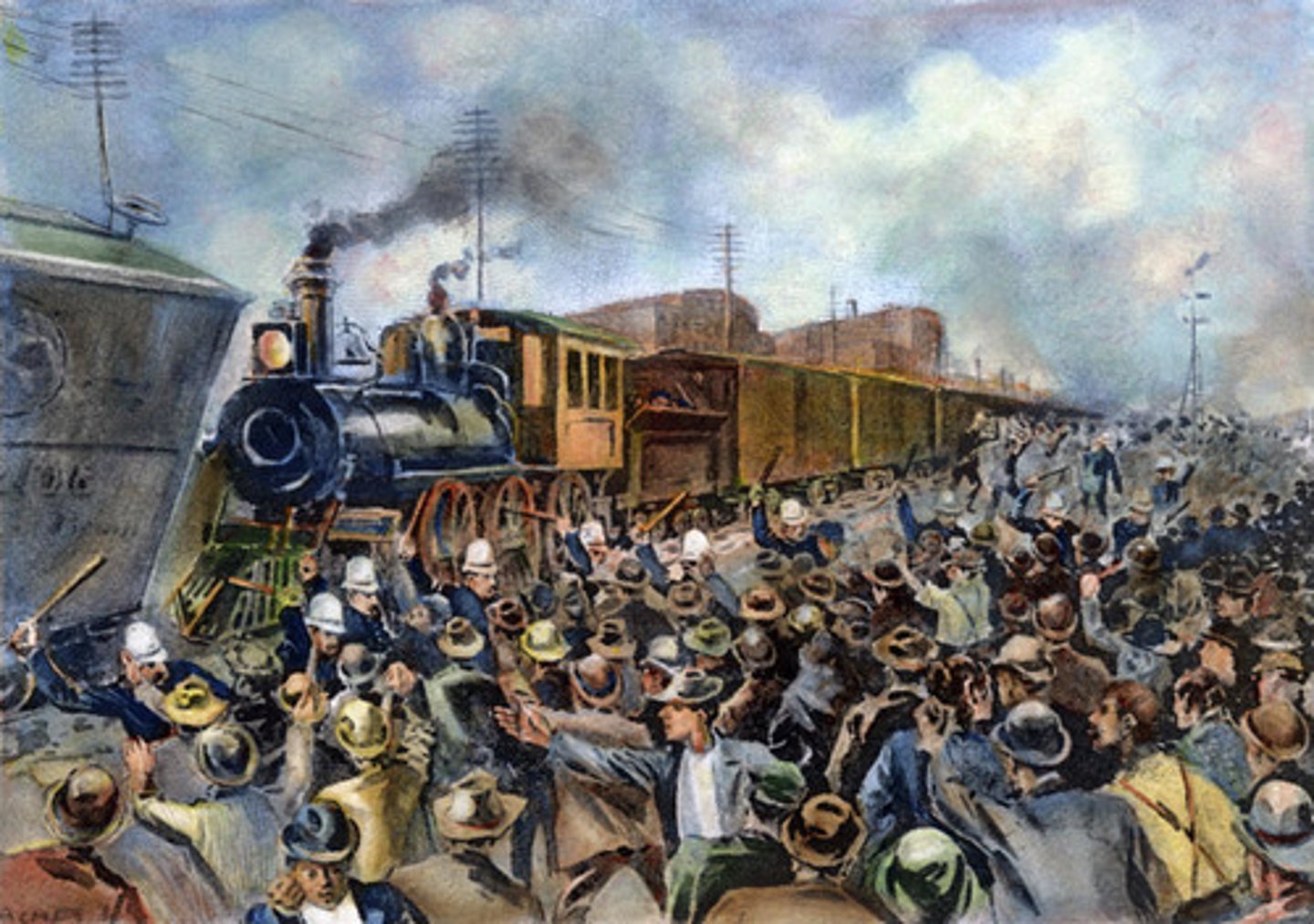

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877

In the first national labor walkout, railway workers protesting a pay cut shut down railroads in much of the country. State militia units trying to force workers back to work fired on strikers in Pittsburg, killing twenty, igniting an outbreak of violence and general strikes in several major cities. In the aftermath of the strike, the federal government constructed armories in major cities to ensure that troops would be on hand in the event of further labor difficulties. Henceforth, national power would be used to protect the rights of property against the labor movement, reflecting the PBBLF spirit of he era.

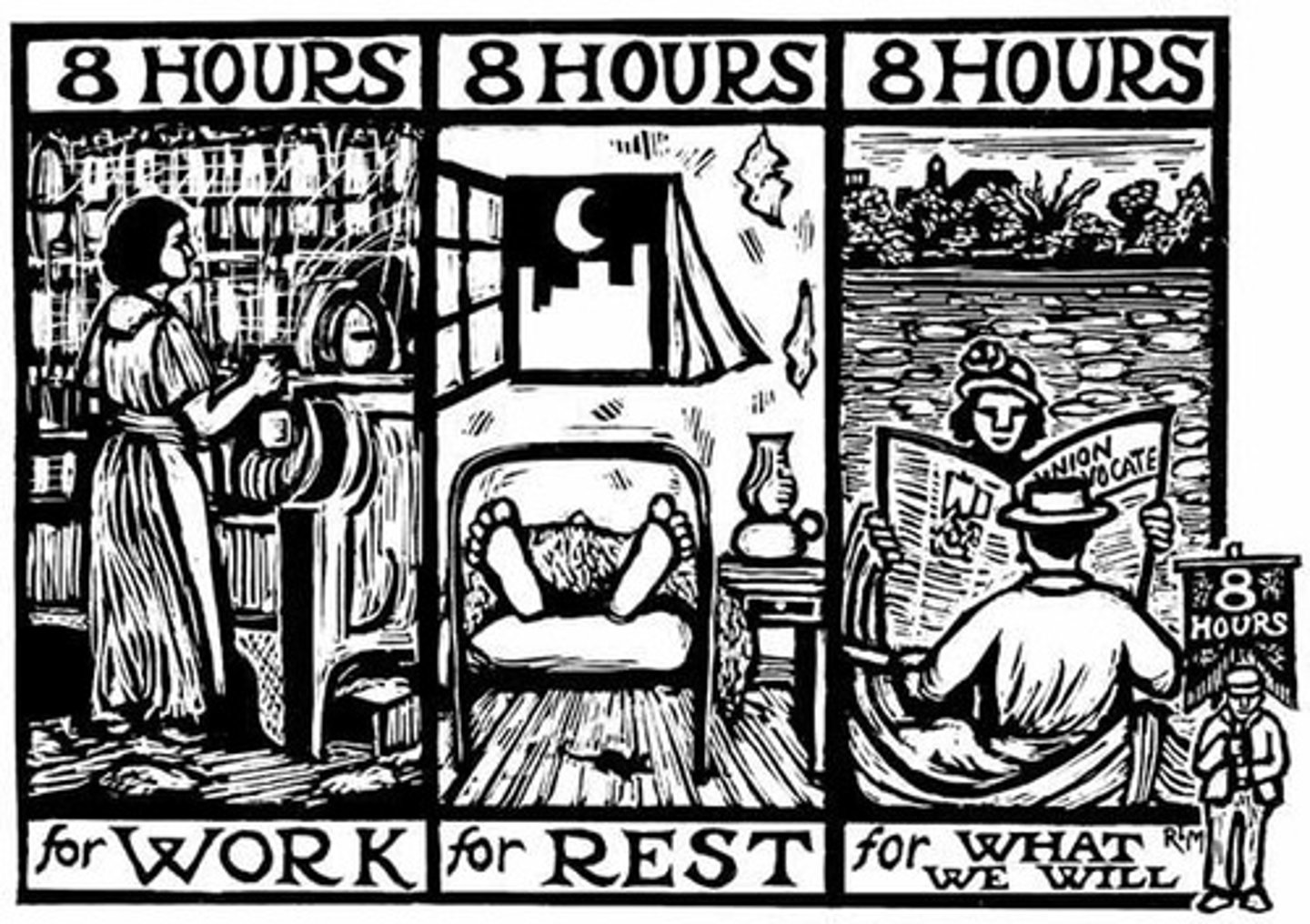

The Knights of Labor

Founded in 1869, this first national union lasted, under the leadership of Terence V. Powderly, only into the 1890s; it was later supplanted by the American Federation of Labor (AFL). But for a time, this union was the first to try to organize unskilled workers as well as skilled, women alongside of men, and blacks as well as whites, and they had ambitious and wide-ranging goals from the eight-hour day, to public employment in hard times, to socialism, to the creation of a "cooperative commonwealth." Note: workers did not have a legal right to form a union until the 1930s, so employers often fired and blacklisted members of unions.

Carnegie's "Gospel of Wealth"

Andrew Carnegie's philosophy that the wealthy had a moral obligation to promote the advancement of society by creating "ladders of opportunity" upon which the aspiring poor could climb. He denounced the "worship of money" and distributed much of his wealthy to various philanthropies, especially to the creation of public libraries.

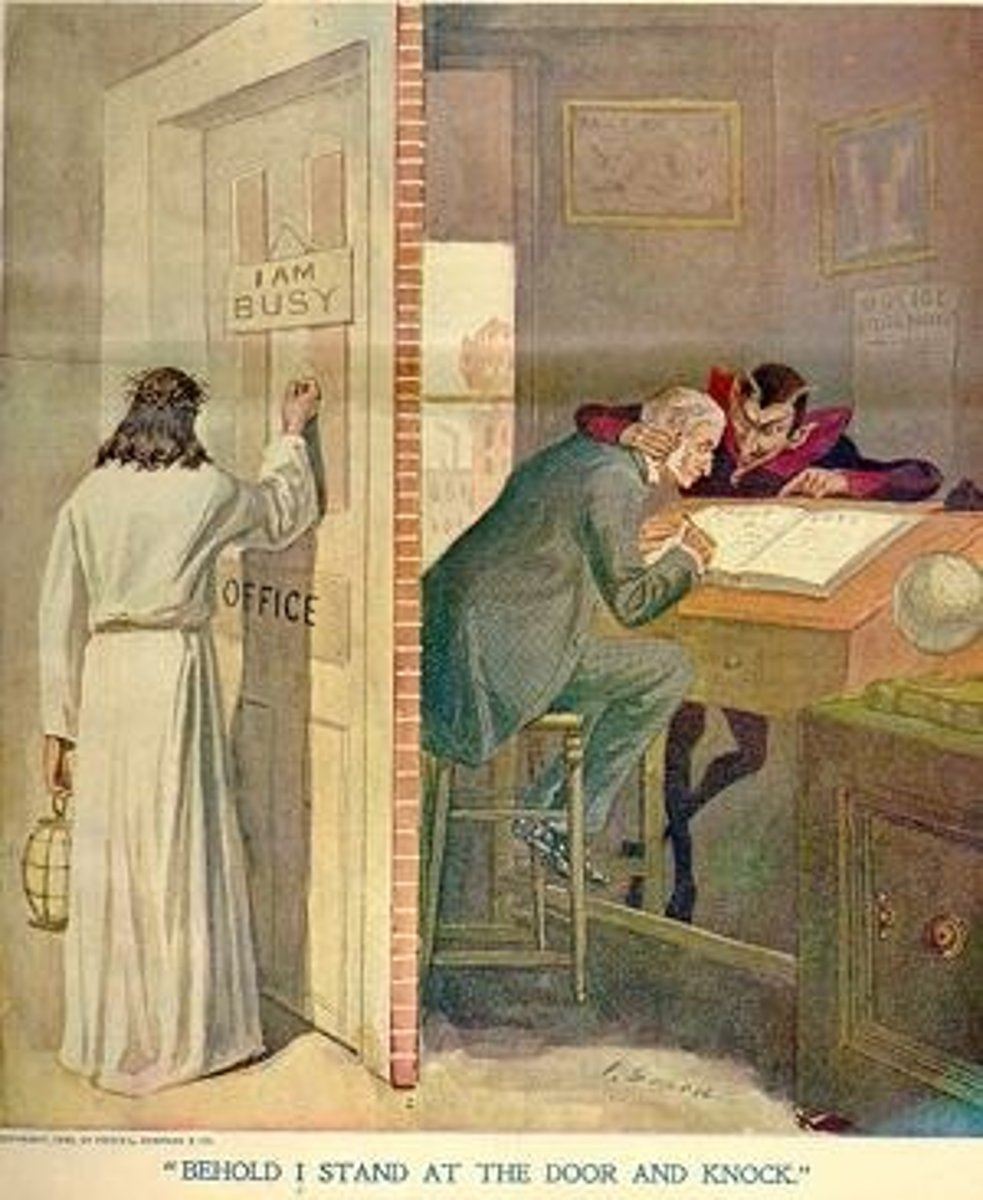

The Social Gospel Movement

A movement of liberal Protestant clergymen in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who preached and advocated for the application of Christian principles to social problems generated by industrialization.

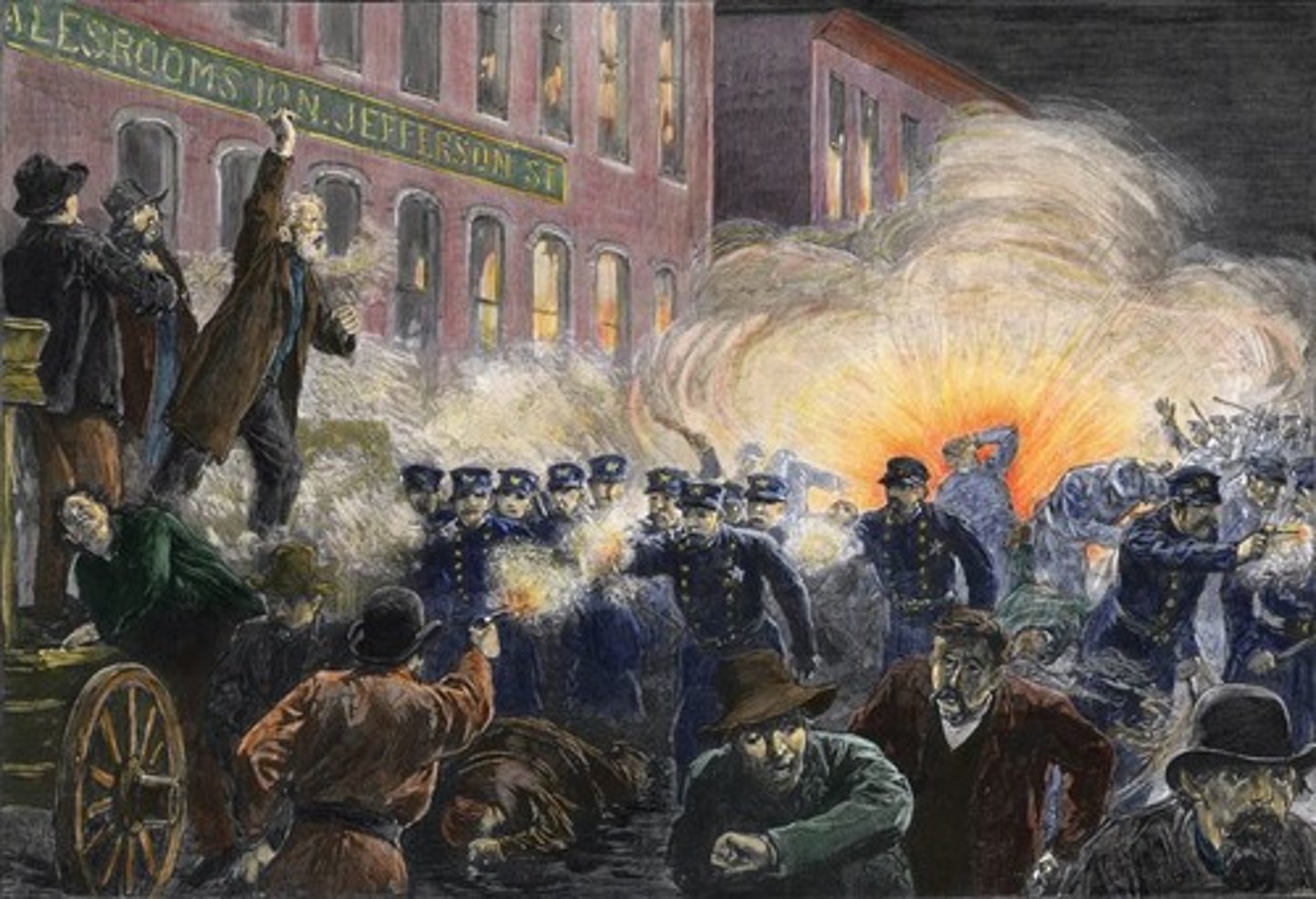

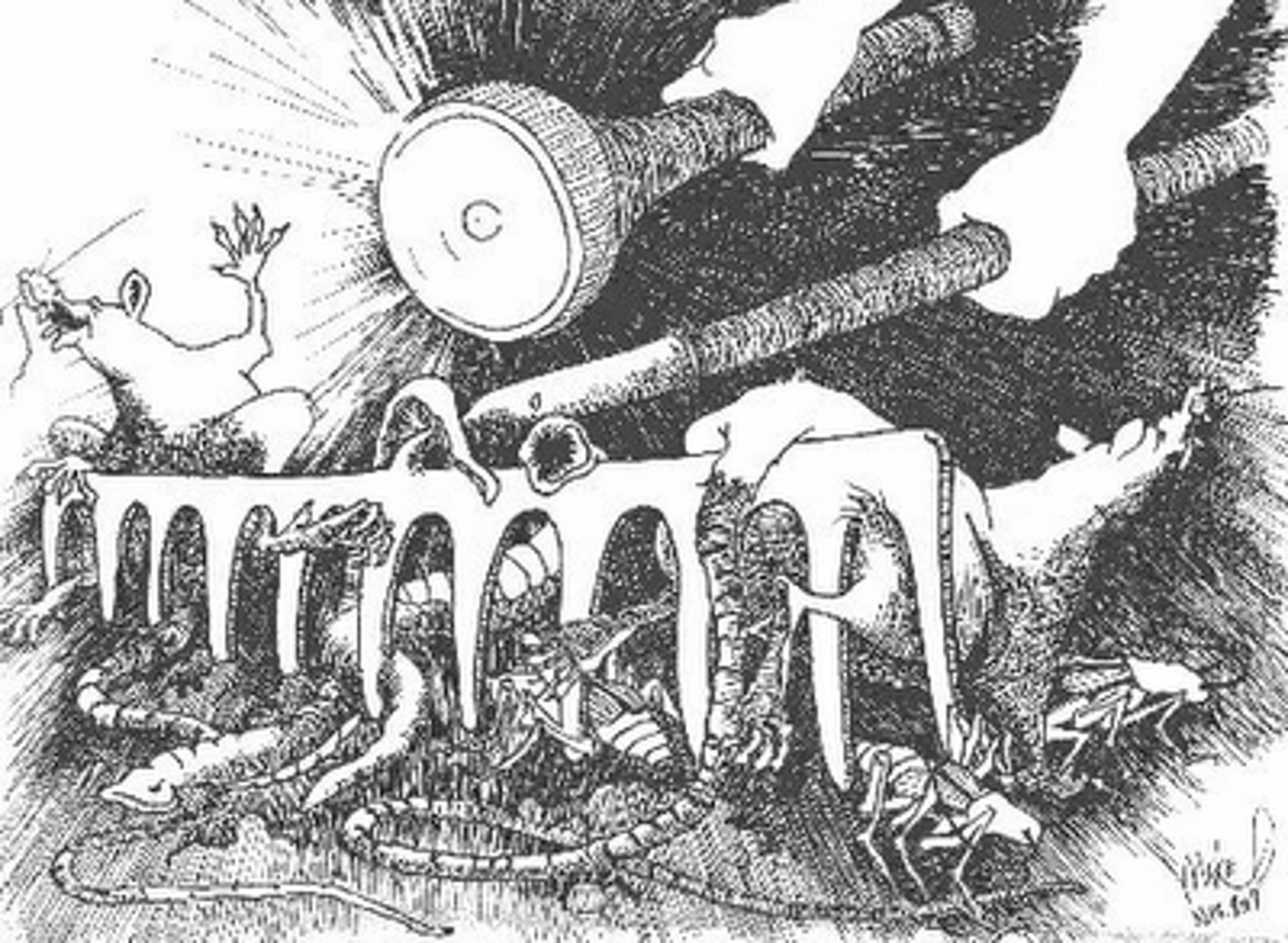

The Haymarket Square Riot, 1886

A major setback for the labor movement, workers were rallying in a public square in Chicago (this event is named after that public square) to protest the shooting and killing of three workers by police the day before who were shot while trying to prevent strikebreakers from entering the factory where they were on strike. During the rally, an unknowing person threw a bomb into a crowd killing a policeman. Interpreting the violence as an attack on the policy by the workers, panicked police opened fire, killing several, and afterwards raided offices of labor and radical groups and arrested their leaders. This event gave employers an opportunity to paint the labor movement as a dangerous and un-American force.

The Homestead Strike, 1892

The nineteenth century's most widely publicized confrontation between capital and labor. A major strike of workers started at Andrew Carnegie's Steel plant in Pennsylvania after Carnegie decided to operate the plant on a non-union basis. After the workers initially beat back hired policemen from the Pinkerton Detective Agency in a battle that left a number dead, the Pennyslvania governor sent in the national guard to reopen the plant on Carnegie's terms. The strikers nevertheless won national sympathy, but the strike was ultimately a failure for the workers, and it demonstrated the enormous power of large corporations, and the government's willingness to support corporate property against the wishes of organized labor, during the Gilded Age.

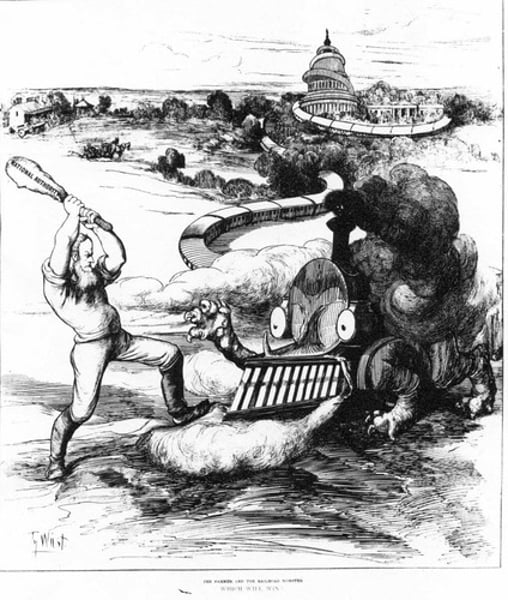

The People's Party, or Populists

This group spoke for all "producing classes" (especially Western farmers) and embarked on a remarkable effort of community organization and education. Founded in the early 1890s, and growing out of the Farmer's Alliance of the 1870s and 80s, they established over 1,000 local newspapers, promoted traveling speakers like Tom Watson and Mary Elizabeth Lease, and held great gatherings across the Western Plains.

The Populist Platform of 1892

A classic document of American reform, it spoke of a nation "brought to the verge of moral, political, and material ruin" by political corruption and economic inequality. The platform put forth a long list of proposals to restore democracy and economic opportunity, many of which would be adopted during the next half-century: the direct election of U.S. senators, government control of the currency, a graduated income tax, a system of low-cost public financing to enable farmers to market their crops, public ownership of railroads, and recognition of the right of workers to form unions.

The Pullman Strike, 1894

A strike by the American Railway Union's 150,000 members, who effectively shut down the nation's rail service when they refused to handle Pullman sleeping cars to protest the reduction of wages at the Pullman company. In response, President Cleveland obtained a federal court injunction ordering strikers back to work, and federal troops and U.S. marshals soon occupied railroad centers like Chicago and Sacramento, which ended the strike.

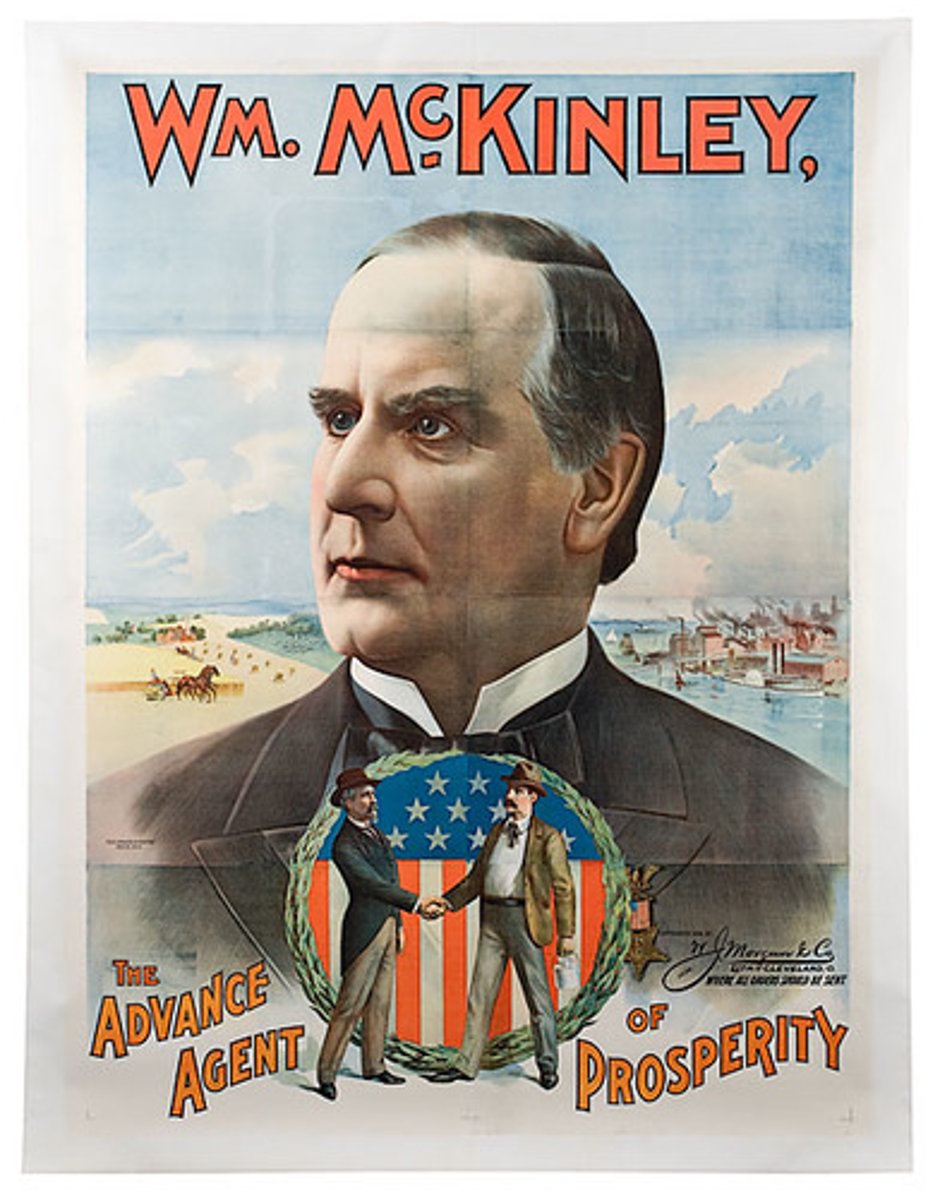

The Election of 1896

In this Presidential election, Populists joined with the Democrats to support William Jennings Bryan, who embraced the Social Gospel and called for free coinage of silver (or the unrestricted minting of silver money), which farmers believed would increase the amount of money in circulation, raise crop prices, and make it easier for farmers to pay off debts. The Republicans nominated William McKinley and defended the Gold Standard. This election is often called the "first modern political campaign" because of the huge amount of money spent by the Republicans and the efficiency of their national organization. The results revealed a nation divided on regional lines: Bryan and the Democrats carried the South and the West. McKinley and the Republicans swept the more populous industrial states of the North. Industrial America, from financiers and managers to workers, now voted Republican; McKinley's victory shattered the political stalemate that had persisted since 1876 and created one of the most enduring political majorities in American History.

Convict-lease system

A system of state laws in the South, developed under the Redeemers, that 1) allowed for the arrest of virtually anyone without employment and increased penalties for petty crimes, and 2)rented out the state's convicted criminals (most of them black) to perform involuntary labor to private businesses for the profit of the state. The convict-lease system effectively exploited the loophole in the Thirteenth Amendment and allowed a form of black slavery to continue in the South long after Reconstruction.

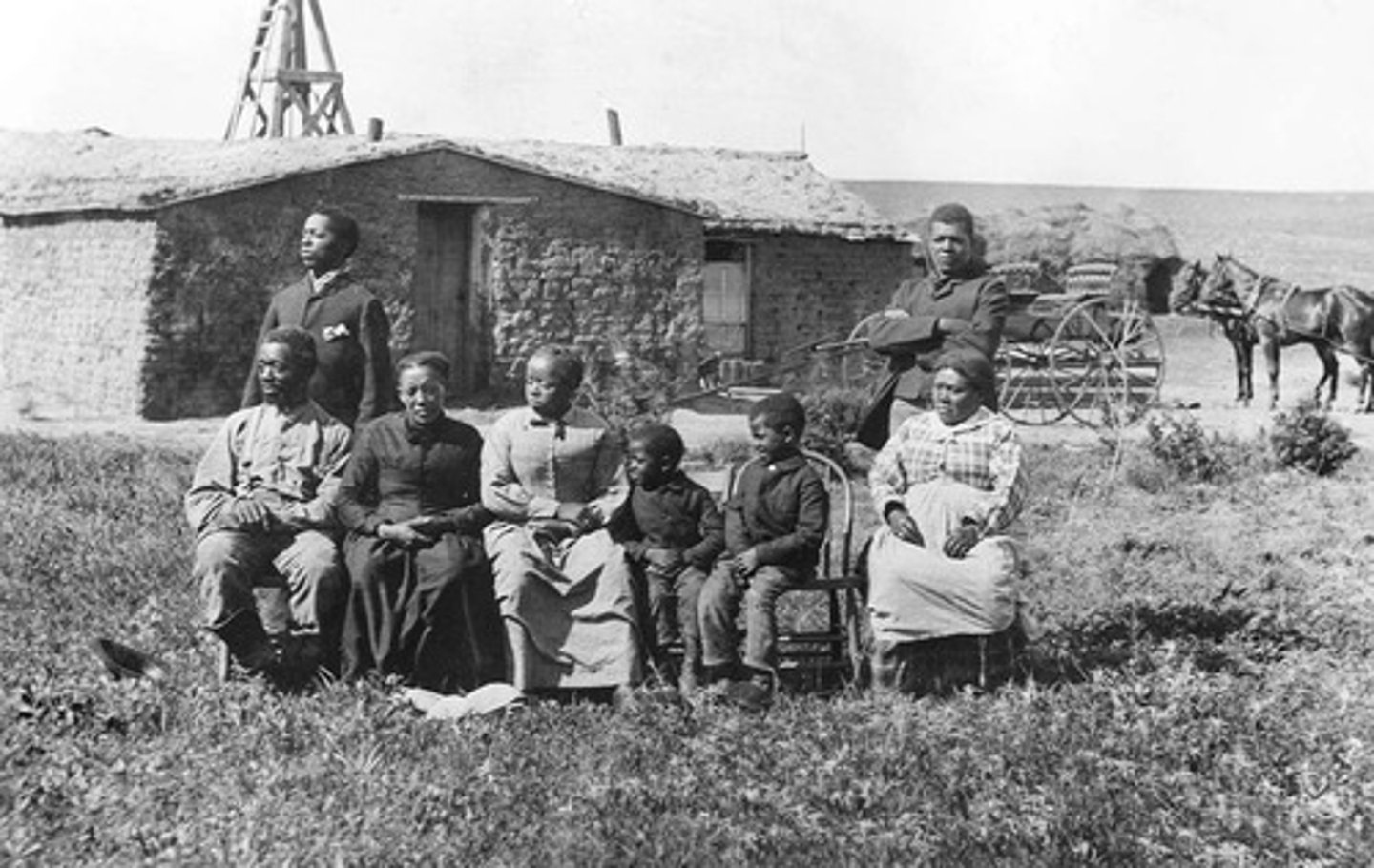

The Kansas Exodus, 1879-80

A migration by some 40,000-60,000 blacks to Kansas to escape the oppressive environment of the New South.

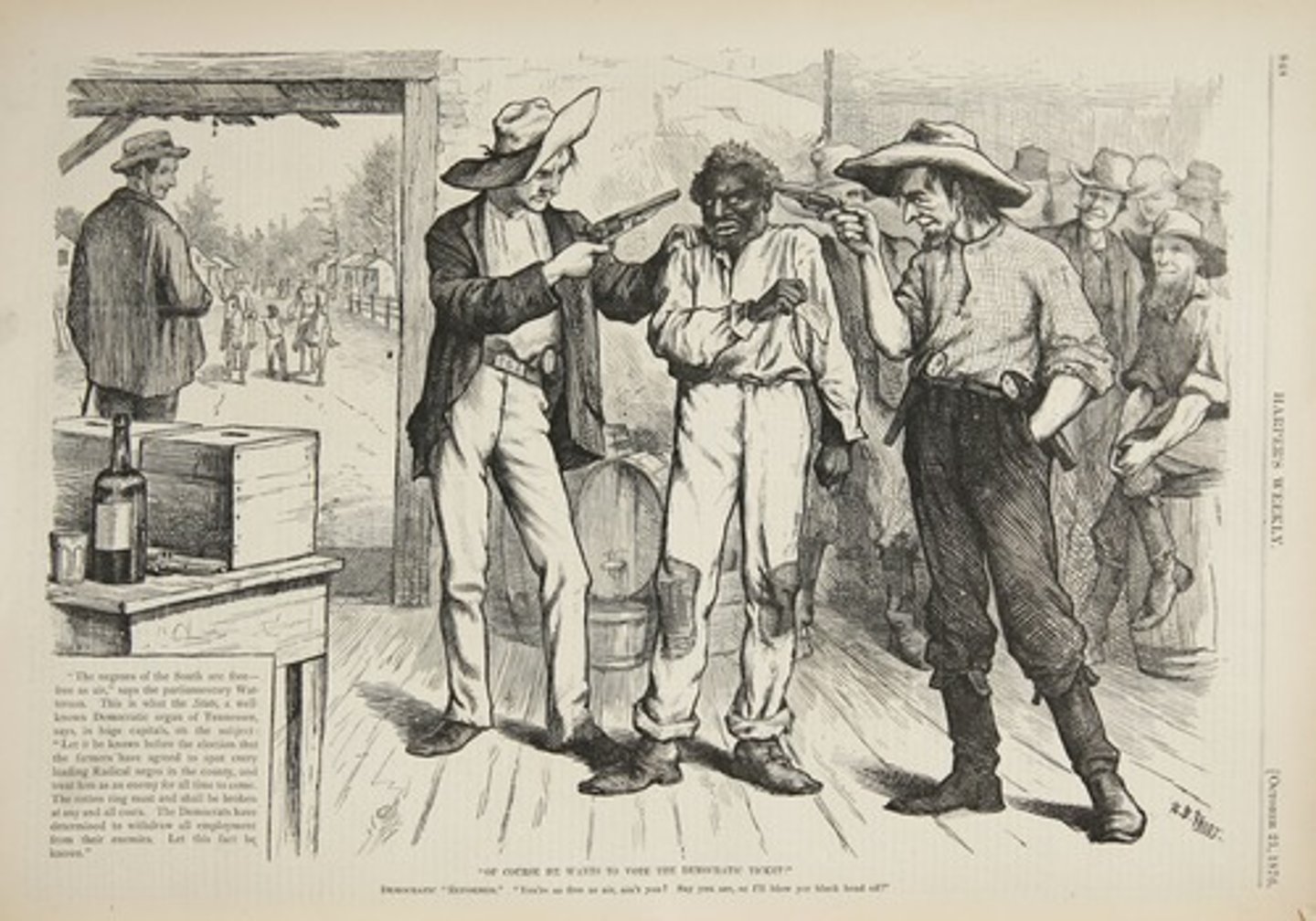

Black Disenfranchisement

Between 1890 and 1906, every southern state enacted laws that used "loopholes" in the 15th Amendment to eliminate the black vote: poll taxes, literacy tests, "understanding clauses," and "grandfather clauses." Additionally, terrorist organizations like the KKK would intimidate and threaten African Americans who attempted to vote.

Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896

In one of the most significant rulings in American history, the U.S. Supreme Court supported the legality of Jim Crow laws that permitted or required "separate but equal" facilities for blacks and whites. In reaction to this decision, states across the South passed laws mandating racial segregation in every aspect of Southern life, from schools to hospitals, waiting rooms, toilets, and cemeteries. Despite the phrase "separate but equal," facilities for blacks were either nonexistent or markedly inferior. The doctrine of "separate but equal" would not be struck down by the Supreme Court until the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954.

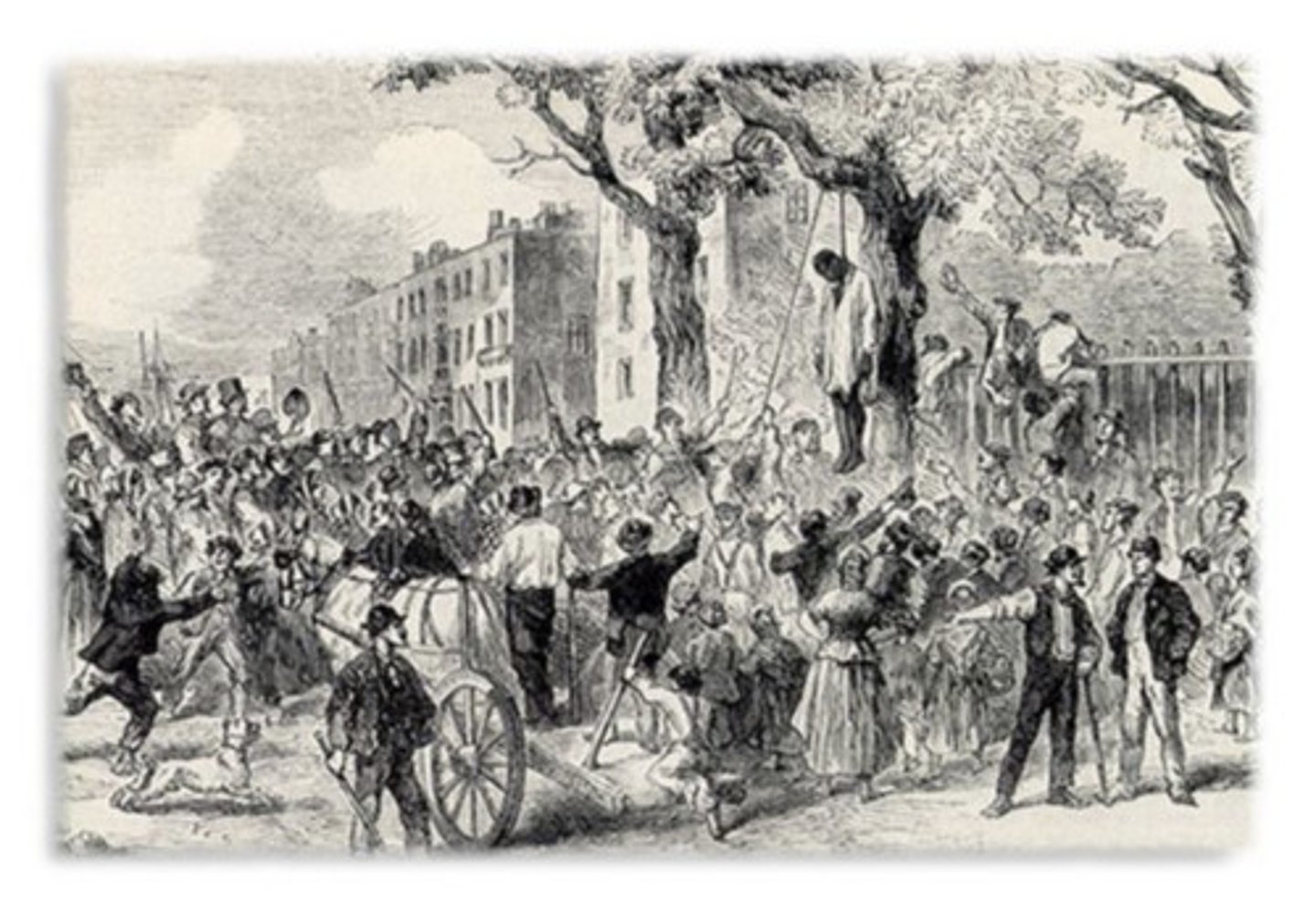

Lynching

A notorious practice, particularly widespread in the South between 1890 and 1940, in which persons (usually black) accused of a crime were murdered by mobs before standing trial. These shocking events often took place before large crowds, with law enforcement authorities not intervening.

Ida B. Wells

African American journalist and the nation's leading anti-lynching activist. She reported on lynchings and documented the fact that the charges against victims of lynching were often untrue.

"Lost Cause" ideology

An ideology that romanticized slavery, the Old South, and the Confederate Cause. It taught that the experiment with multiracial democracy during Radical Reconstruction had been a foolish mistake. During the Gilded Age and early 20th century, Southern states throughout the region built monuments honoring leaders of the Confederacy.

the "new immigrants"

During the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era, this term referred to immigrants from southern and eastern Europe who composed the largest wave of immigrants in U.S. history to that point and were described by many native-born Americans as belonging to distinct and inferior races. The first wave of voluntary immigrants to the U.S. had arrived during the Colonial Era and had come overwhelmingly from Great Britain. The second major wave arriving in the middle of the 19th century had come largely from Ireland and Germany. Now, this third major wave--20 million between 1880 and 1920--was coming increasingly from southern and eastern European nations whose populations were predominantly Catholic and Jewish.

Immigration Restriction League

Founded in 1894, this was a group that called for the reduction of immigration to the United States. They accused the "new immigrants" (largely Catholics and Jews coming from southern and eastern Europe) of undercutting wages, taking American jobs, being incapable of intelligent participation in democratic government, and spreading crime and disease, and poverty. Throughout its history, the United States has admitted more immigrants than any other nation in the world, and yet at times, nativist sentiment pops up.

Booker T. Washington's Atlanta Compromise Speech, 1895

An 1895 speech in which Booker T. Washington rejected the abolitionist tradition that stressed ceaseless agitation for full equality, and instead, he urged blacks not to try to combat segregation. He advocated industrial education and economic self-help to gain practical skills and vocational training in order to acquire some power in the economy. He said, "In all things purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress." This moderate and accommodationist approach would be challenged during the Progressive Era by more militant black leaders like W. E. B. Du Bois and Marcus Garvey.

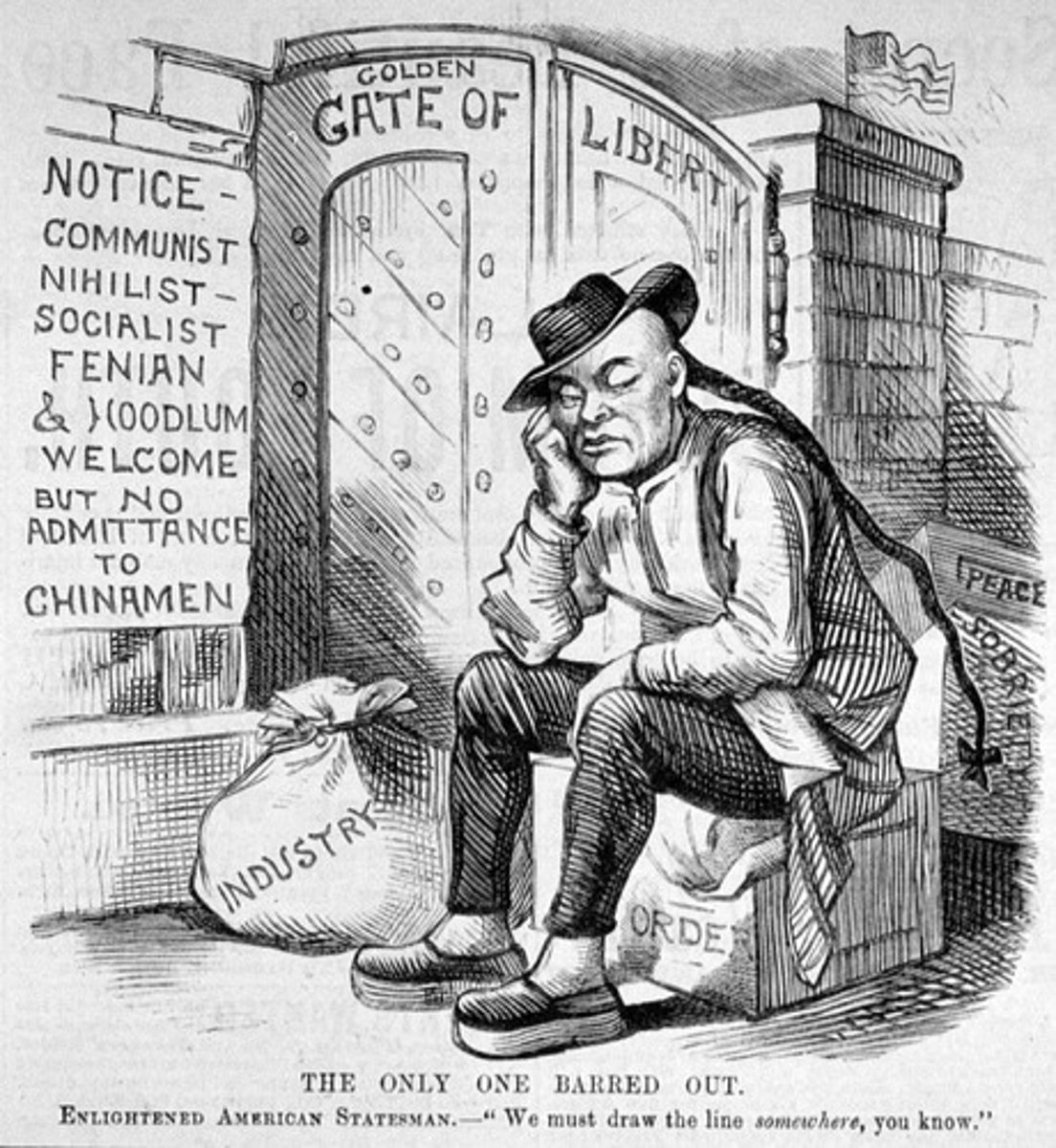

The Chinese Exclusion Act, 1882

A federal law barring immigrants from China from entering the U.S.. The law was first a temporary ban, but it was extended and made permanent in 1902. Although non-whites had long been barred from becoming naturalized U.S. citizens, this was the first time race was used to exclude an entire group of people from entering the U.S.. This law was created at a time of widespread discrimination against and violence towards Chinese Americans, particularly on the West Coast, where about 105,000 Chinese Americans lived, and it also reflected the growing nativism and slow contraction of the boundaries of nationhood occurring during the Gilded Age.

The American Federation of Labor (AFL)

Founded in 1881, this grew and became the largest national federation of labor unions between the 1890s and 1950s. Rejecting socialism, this was more conservative than the radial Knights of Labor. Its goals were more limited (focusing on securing higher wages and better working conditions) than the Knights of Labor, and it admitted mostly skilled, white, native-born workers, and was thus also less inclusive than the Knights of Labor. Samuel Gompers served as its long-term president from its founding in the Gilded Age until Gompers' death in 1924.

"The Women's Era" (1890-1920)

Three decades starting from the 1890s, during which women, although still denied the vote at the national level, enjoyed larger opportunities than in the past for economic independence (with nearly every state abolishing its coverture laws) and greater roles in public life through a network of women's clubs, temperance associations, and social reform organizations.

Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU)

The largest progressive female reform organization of the late 19th century, it expanded its platform from simply prohibiting alcoholic beverages (which they blamed for leading men to squander their wages on booze and to treat their wives abusively) to a comprehensive program of economic and political reform, including the right to vote.

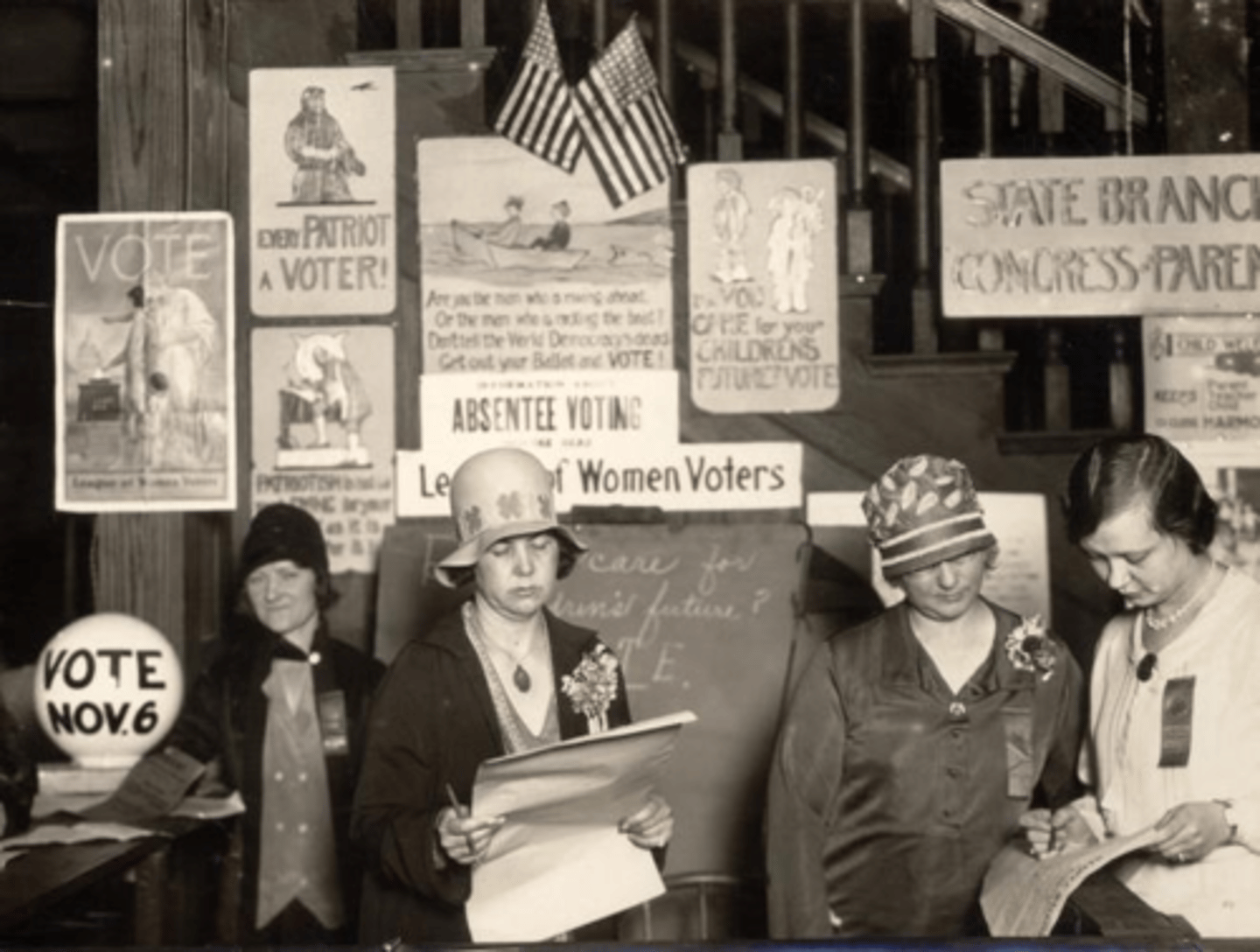

Carrie Chapman Catt and the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA)

President of the NAWSA (which had been created in 1890 to reunite the rival suffrage organizations formed after the Civil War), she reflected the era's narrowed definition of nationhood by suggesting that the native-born, middle-class women who dominated the suffrage movement deserved the vote as members of a superior race and that educational and other voting qualifications did not conflict with the movement's aims, so long as they applied equally to men and women.

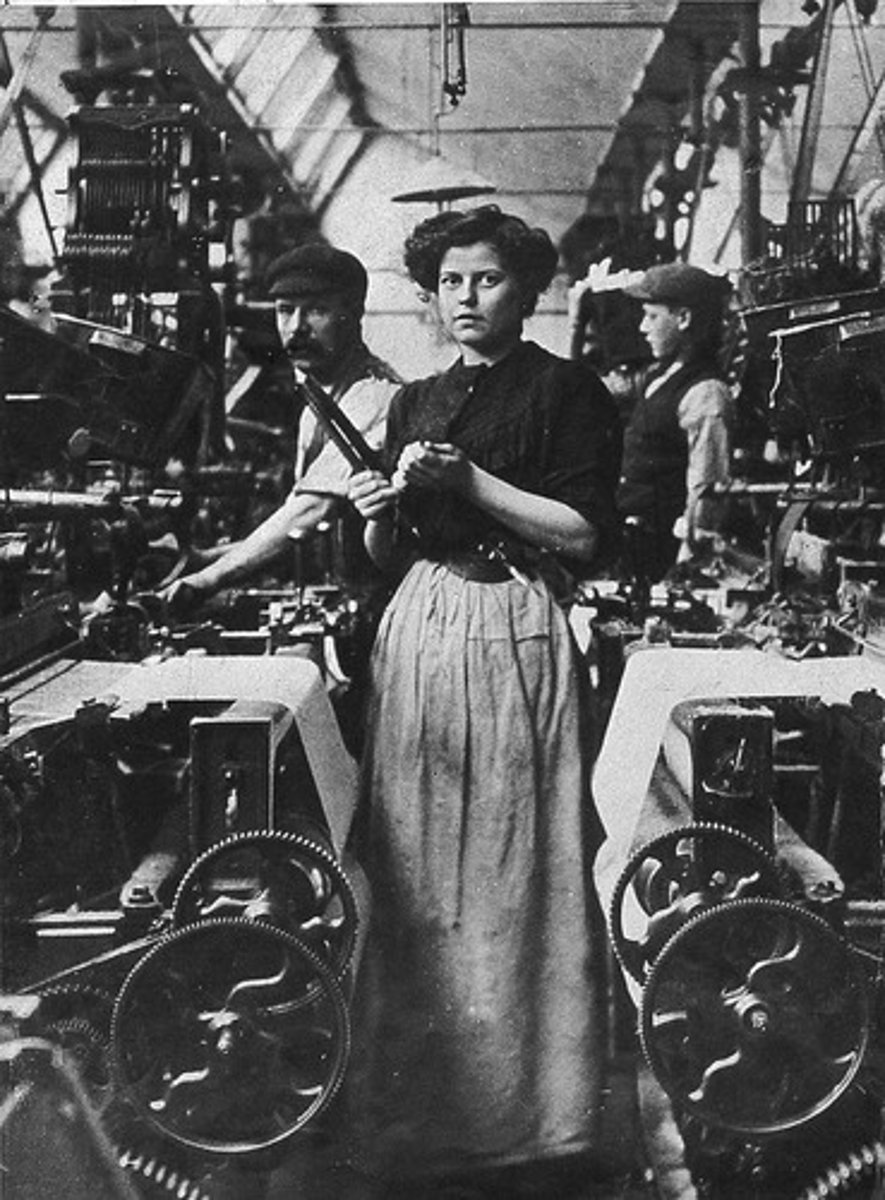

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, 1911

In 1911, a fire broke out at this company in New York City. Inside, some 500 workers, mostly young Jewish and Italian immigrant women, toiled at sewing machines, earning as little as three dollars per week. Those who tried to escape the blaze discovered that the doors to the stairwell had been locked--the owner's way of discouraging theft and unauthorized bathroom breaks. The fire department rushed to the scene with water hoses, but their ladder could only reach the sixth floor. As the fire raged, girls leapt from the upper stories. By the time the blaze was put out, 46 bodies lay on the street and 100 more were found inside the building. This event led to accelerated efforts to organize the city's workers and the passing of state legislation for new factory inspection laws and fire safety codes. It became a became a classic example of why government needed to regulate industry.

The Progressive Movement

This term came into common use around 1910 as a way of describe a broad, loosely defined political movement of individuals and groups who hoped to bring about significant change in American social and political life. This movement included forward-looking businessmen who realized that workers must be accorded a voice in economic decision making, labor activists bent on empowering industrial workers, female reform organizations who hoped to protect women and children from exploitation, social scientists who believed that academic research would help to solve social problems, and members of an anxious middle class who feared that their status was threatened by the rise of big-business.

The Progressive Era

A periodization concept used by historians to refer to the era from 1900-1914, roughly spanning the Presidential administrations of Teddy Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and William McKinley (until the outbreak of World War One), during which the Progressive Movement sought to find political solutions to many of the problems created by the Second Industrial Revolution.

Muckrakers

Originally a term of disparagement coined by Teddy Roosevelt, this term came to refer to writers who exposed corruption and abuses in politics, business, meatpacking, child labor, and more, primarily in the first decade of the twentieth century; their popular books and magazine articles spurred public interest in reform. They include the following people and books: Jacob Riis's How the Other Half Lives (1890), Lincoln Steffens' The Shame of the Cities (1904), Ida Tarbell's The History of the Standard Oil Company (1904), and Upton Sinclair's The Jungle (1906).

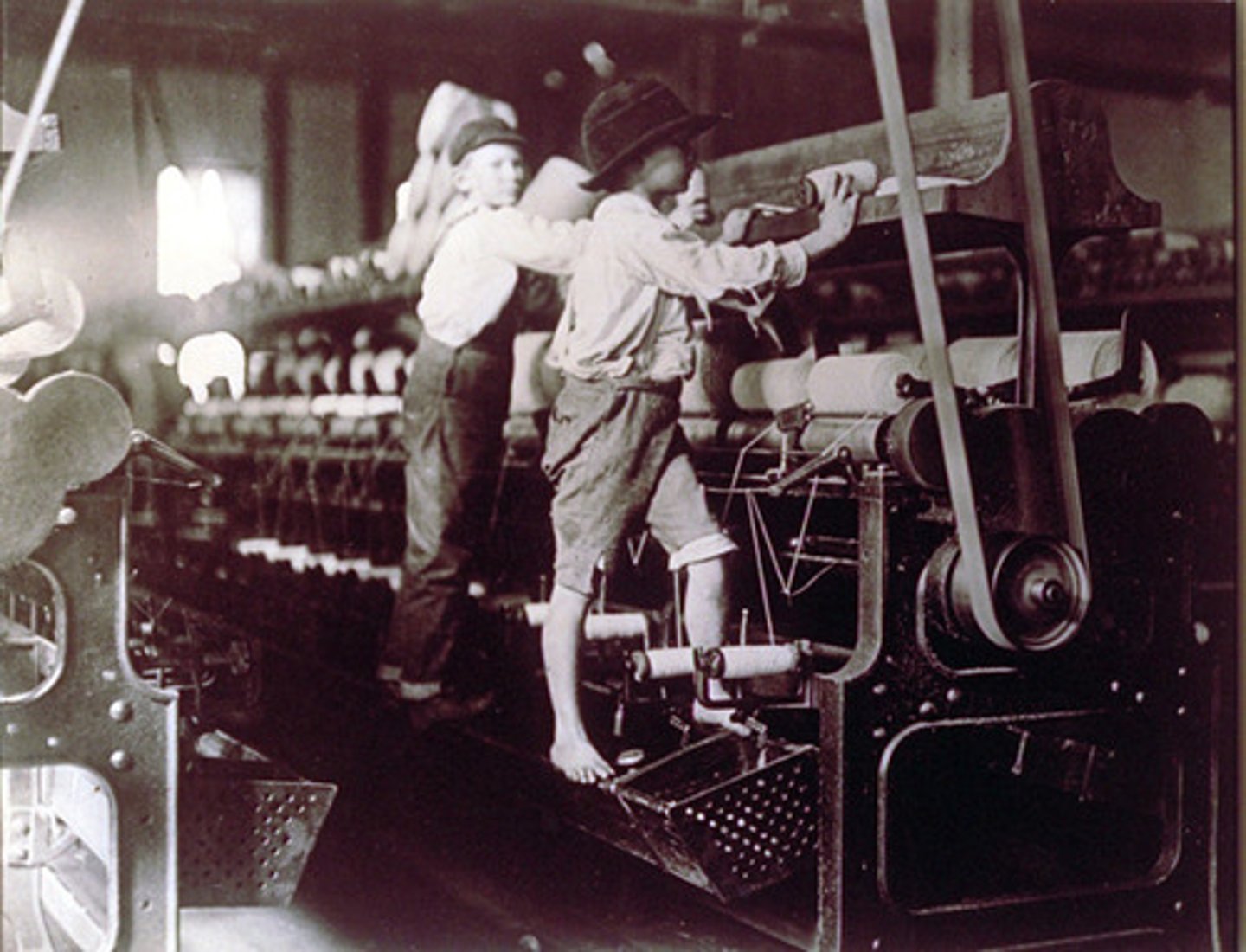

Child Labor

In the early twentieth century, more than two million children under the age of fifteen worked for wages. Many Progressives worked end this practice and achieved only mixed results.

Ellis Island and Angel Island

The first was the reception center in New York Harbor through which most European immigrants to America were processed from 1892 to 1954. The second was in San Francisco Bay and served as the main entry point for immigrants from Asia.

The "new immigration"

Between 1870 and 1920, almost 25 million immigrants arrived from overseas. Increasingly, immigrants arrived not from Ireland, England, Germany, or Scandinavia (the traditional sources of immigration), but instead from southern and eastern Europe, especially from Italy and the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires, and many were Catholic or Jewish. They were widely described by native-born Americans as members of distinct "races" whose "lower level of civilization" posed a threat to the dominance of WASPS (white, anglo-saxon, protestants) in the U.S.

Limited economic opportunity and political turmoil were often among the numerous "push factors" causing immigrants to leave their homeland, and expectations of greater economic opportunity (often jobs in new industrial factories or on farms in newly opened western lands) as well as social, cultural, and political freedoms were likewise common among the "pull factors" attracting migrants to the U.S..

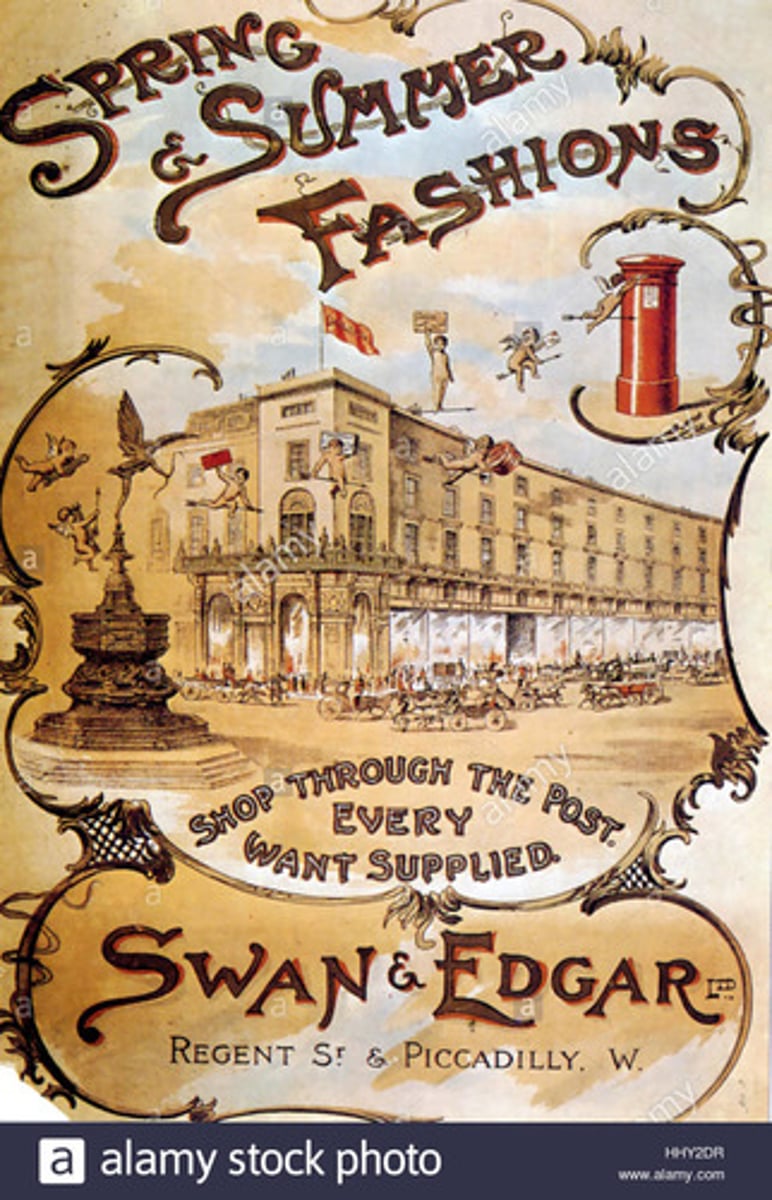

Consumer freedom and mass-consumption

A social and economic ideal that encouraged the purchase of consumer goods as a way to realize freedom. It was during the Progressive Era that the promise of mass consumption became the foundation for this new understanding of freedom as access to the cornucopia of goods made available by modern capitalism. Large, downtown department stores, chain stores in urban neighborhood, and retail mail-order houses for farmers and small-town residents made available to consumers throughout the country the vast array of goods now pouring from the nation's factories. Leisure activities too took on the the characteristics of mass consumptions: amusement parks, dance halls, and theaters attracted large crowds.

The "working woman"

During the Progressive Era, more and more women were working for wages. For native-born white women, the kinds of jobs available expanded enormously. Despite continued wage discrimination and exclusion from many jobs, the working woman--immigrant and native, working class and professional--became a symbol of female emancipation

Henry Ford and "Fordism"

The ideology of the founder of Ford Motor Company, which pioneered a business plan based on mass production and mass consumption. More specifically, Ford's system produced standardized, simple "Model T" automobiles (with nothing handmade or expensive to produce) targeted not to the elite consumer, but rather to the common man. He mass-produced them on the moving assembly line so as to greatly expand output by reducing the time it took to produce each car. He aggressively opposed unions among his employees. And yet he paid much higher wages than other employers, enabling him to attract a steady stream of skilled workers, and enabling his workers to purchase what they made.

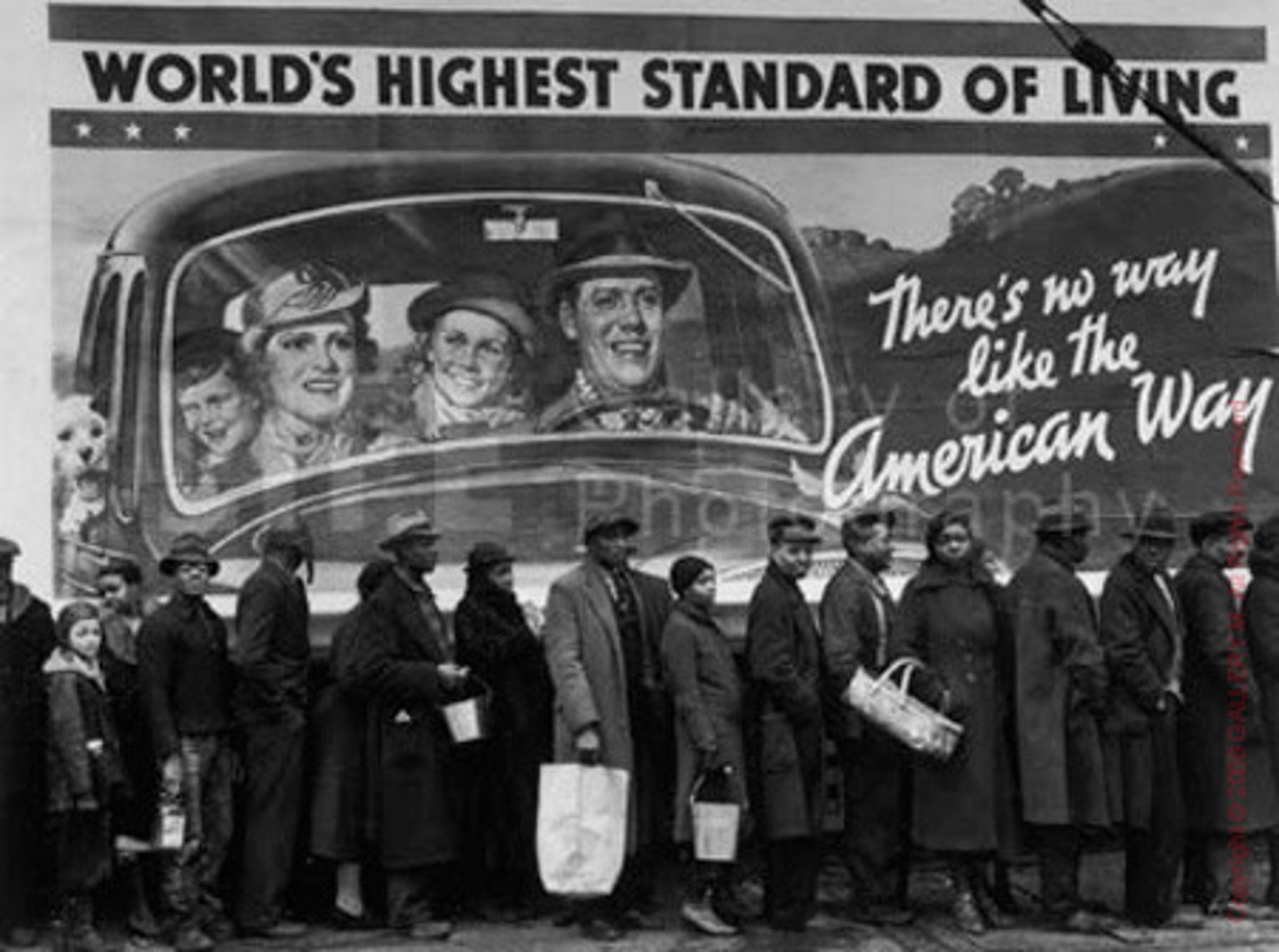

"American standard of living"

The maturation of the consumer economy gave rise to this popular, new concept that reflected, in part, the emergence of a mass-consumption society during the Progressive Era and was used to criticize the growing economic inequality in the nation.

Frederick W. Taylor's "scientific management," or "Taylorism"

A program that sought to streamline production and boost profits by systematically controlling costs and work practices. Through this process, the "one best way" of producing goods could be determined, and workers must obey these detailed instructions from supervisors. Not surprisingly, many skilled workers saw this as a loss of freedom.

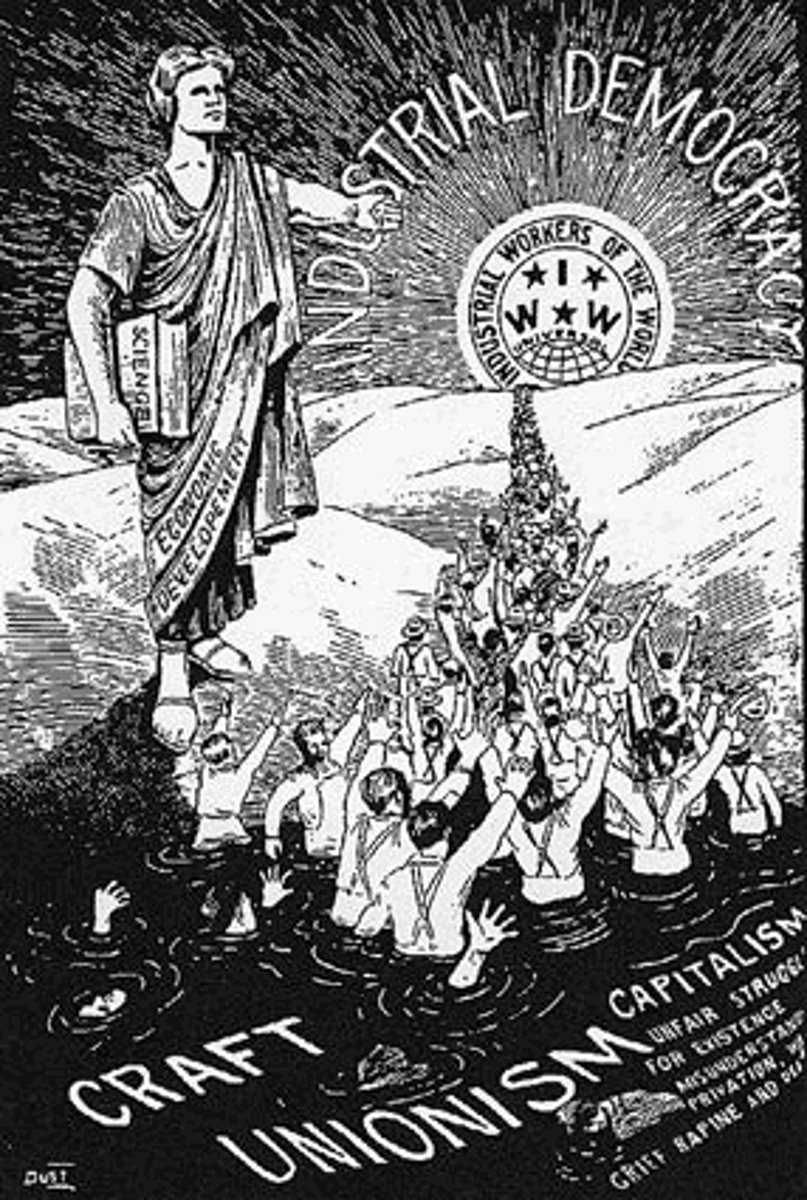

"Industrial Freedom" and "Industrial democracy"

The central demands of workers in the Progressive Era, these terms referred to empowering workers to participate in the economic decisions of their company via strong unions. They were considered to be the solution to the "labor problem" by many in the Progressive Era. Throughout the Gilded Age, workers had experienced a loss of freedom in the workplace and an undermining of their personal autonomy because of developments like Taylorism, the growth of white-collar work, and the declining odds of one day managing one's own business.

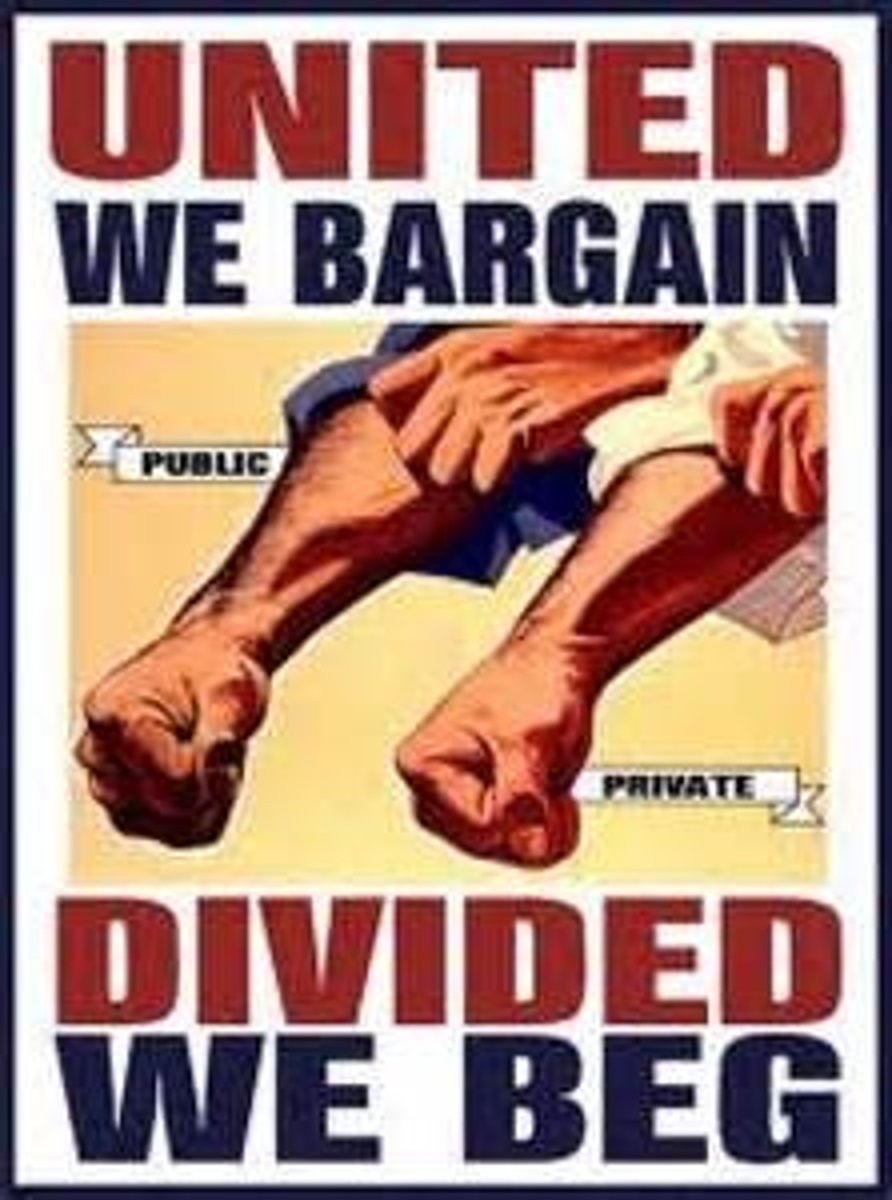

Collective bargaining

By using strength in numbers, this is the process whereby a group of employees organizes together as a union in order to negotiate with their employer. Unions generally aimed to secure higher wages, shorter hours, and better working conditions through these negotiations with their employer.

American socialism

Socialism in the U.S. reached its greatest influence during the Progressive Era. The American Socialist Party, founded in 1901, called for free college education, legislation to improve conditions of laborers, and, as an ultimate goal, democratic control over the economy through public ownership of railroads and factories.

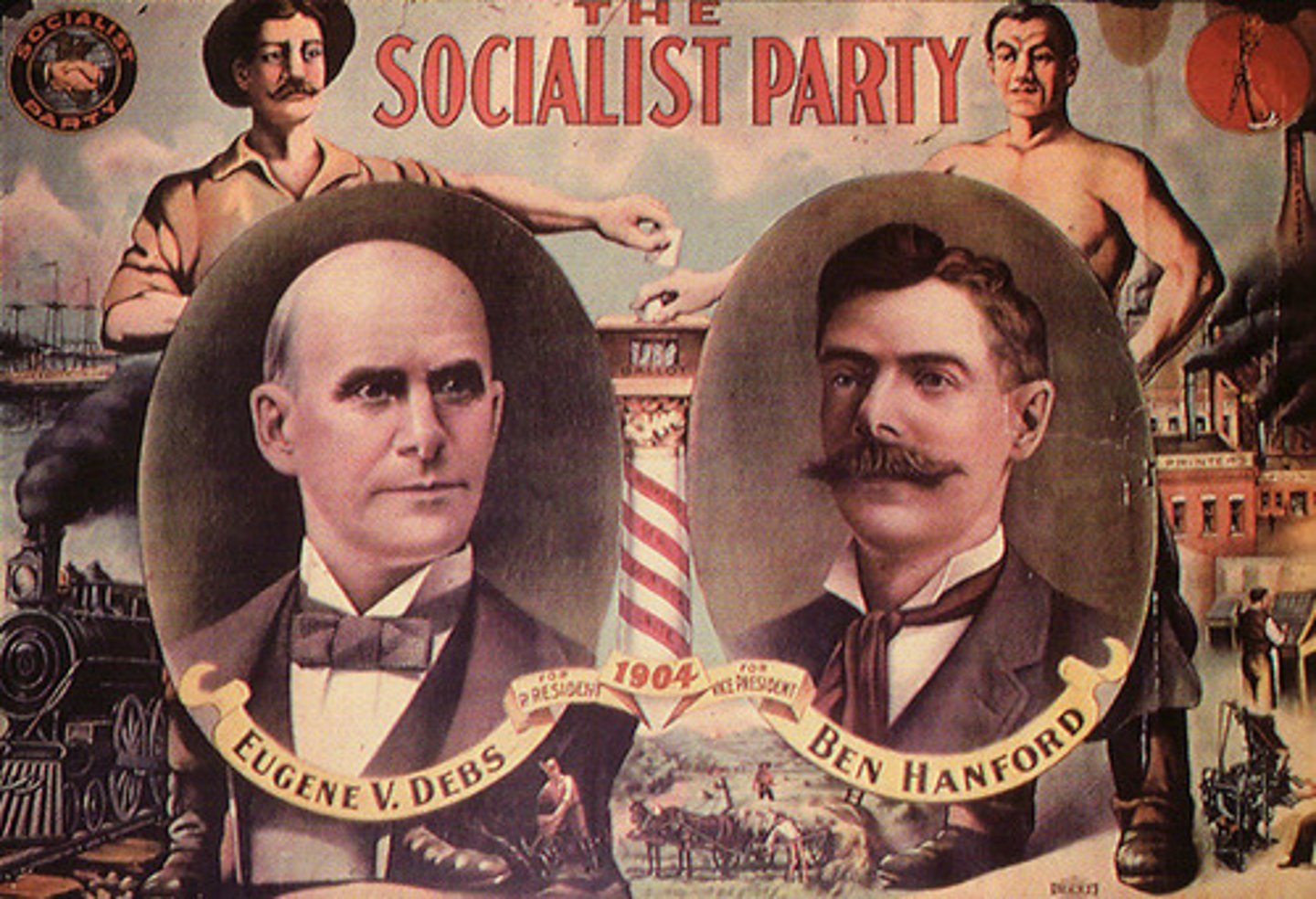

Eugene Debs

The best known socialist in the U.S., no one was more important in spreading the socialist message or linking it to ideals of equality, self-government, and freedom. A champion of the downtrodden, he was one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World, and five times the candidate of the Socialist Party of America for President of the United States; director of the Pullman strike; he was imprisoned along with his associates for ignoring a federal court injunction to stop striking.

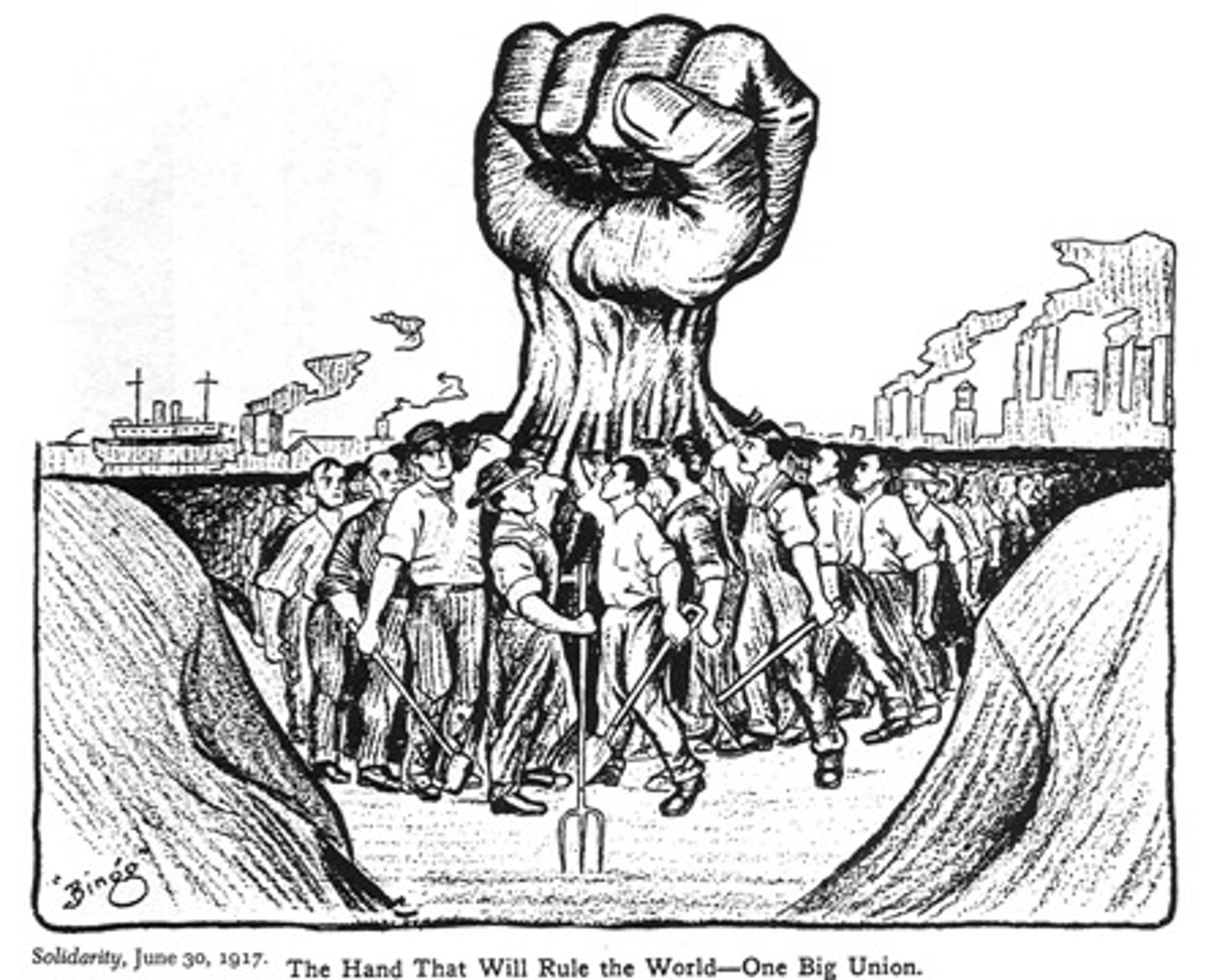

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)

This was a radical union organized in Chicago in 1905 and nicknamed "the Wobblies." Part trade union, part advocate of a workers' revolution that wanted to seize the means of production and abolish the state, the Wobblies rejected the AFL's exclusionary policies and made "solidarity" its guiding principle, extending "a fraternal hand to every wage-worker, no matter what his religion, fatherland, or trade." Its organizers also participated in many of the "free speech fights" of the era, and its opposition to World War I led to its destruction by the federal government under the Espionage Act.

"Bread and Roses"

A slogan of the labor movement that first emerged in the Lawrence, Massachusetts strike of 1912. The slogan was a metaphor declaring that workers sought not only higher wages but also the opportunity to enjoy the finer things in life.

The New Feminism

During the Progressive Era, the word "feminism" first entered the political vocabulary. It referred to Women's emancipation, or equality, in the social, economic, cultural, and sexual spheres.

Margaret Sanger and the birth control movement

A reform movement espousing the idea that the right to control of one's body included the ability to enjoy an active sexual life without necessarily bearing children. The most prominent activist associated with this movement was one of eleven children, and she challenged laws that had banned contraceptive

Information and devices by openly advertising birth control devices in her journal, The Call, and distributing them in her clinic in Brooklyn.

The Society of American Indians and Carlos Montezuma

Founded in 1911, this was a reform organization (critical of of federal indian policy) that brought together Indian intellectuals to promote discussion of the plight of Native Americans in the hope that public exposure would be the first step toward remedying injustice. Members of S.A.I came from many different Indian tribes, but because many had been been educated in government boarding schools, they were able to create one of the first pan-Indian organizations independent of white control. This prominent founder of S.A.I., established the newsletter Wassaja, which called for greater Indian self-determination and independence from the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

State level Progressives

Because of the decentralized nature of American government, state and local governments enacted most of the Progressive Era's reforms measures. In cities, Progressives worked to reform the structure of government to reduce the power of political bosses, establish public control over "natural monopolies" like gas and water works, and improve public transportation. They raised property taxes in order to spend more money on schools, parks, and other facilities. Important progressive reformers working at the state and local levels included Hazen Pingree, Samuel "Golden Rule" Jones, Hiram Johnson, and Robert LaFollette.

16th Amendment (Graduated Income Tax), 1913

This Constitutional Amendment during the Progressive Era established the federal income tax. A "graduated" tax, or a "progressive" tax, is one in which taxpayers with higher incomes are taxed at higher rates than those with lower incomes.

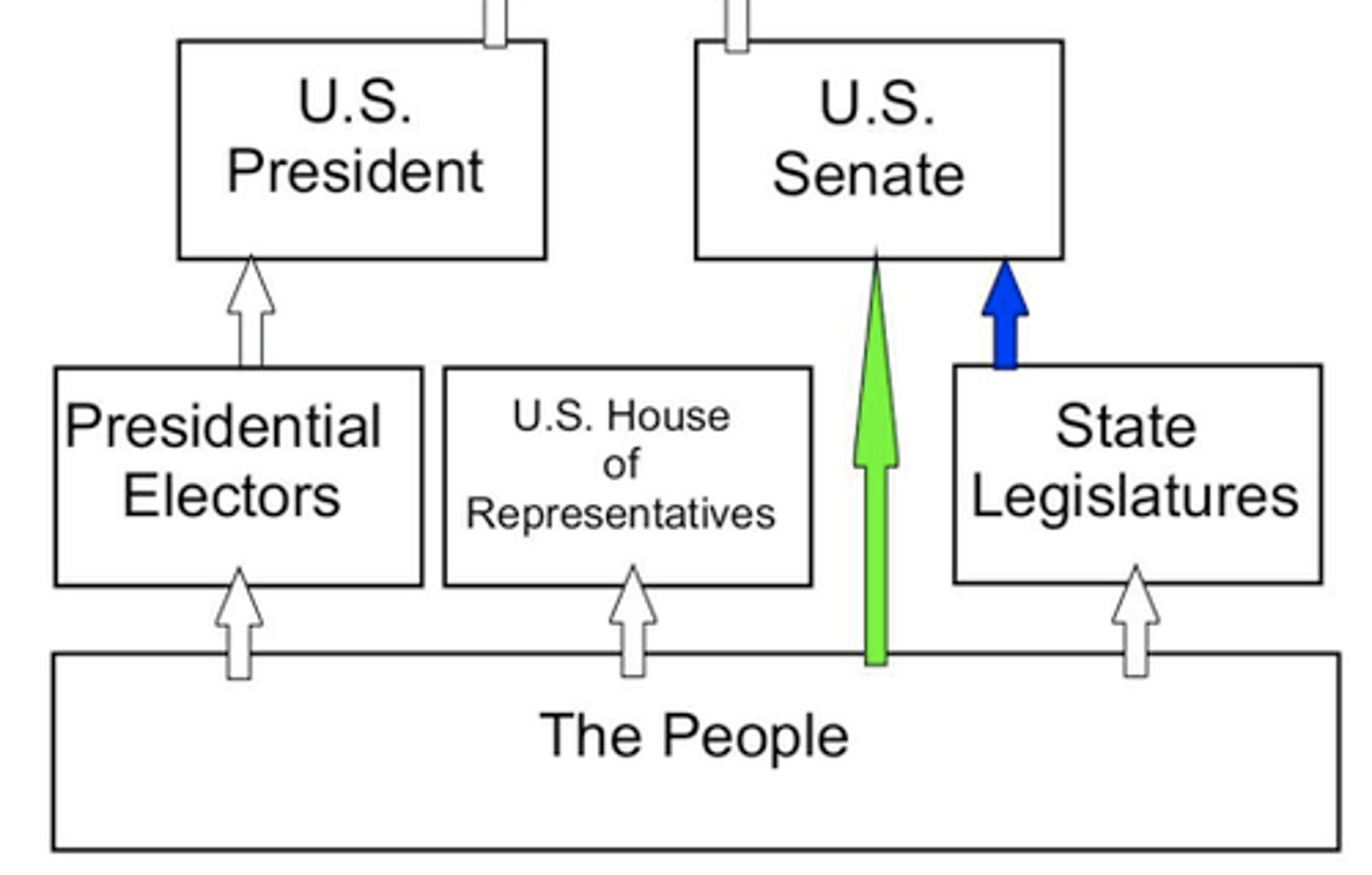

17th Amendment (Direct Election of Senators), 1913

Progressive reform that required U.S. senators to be elected directly by voters; previously, senators were chosen by state legislatures.

18th Amendment (Prohibition), 1919

Outlawed the manufacture, sale, and transportation (but not consumption) of alcoholic beverages. It became the only Amendment ever to be repealed when the 21st Amendment was ratified in 1933.

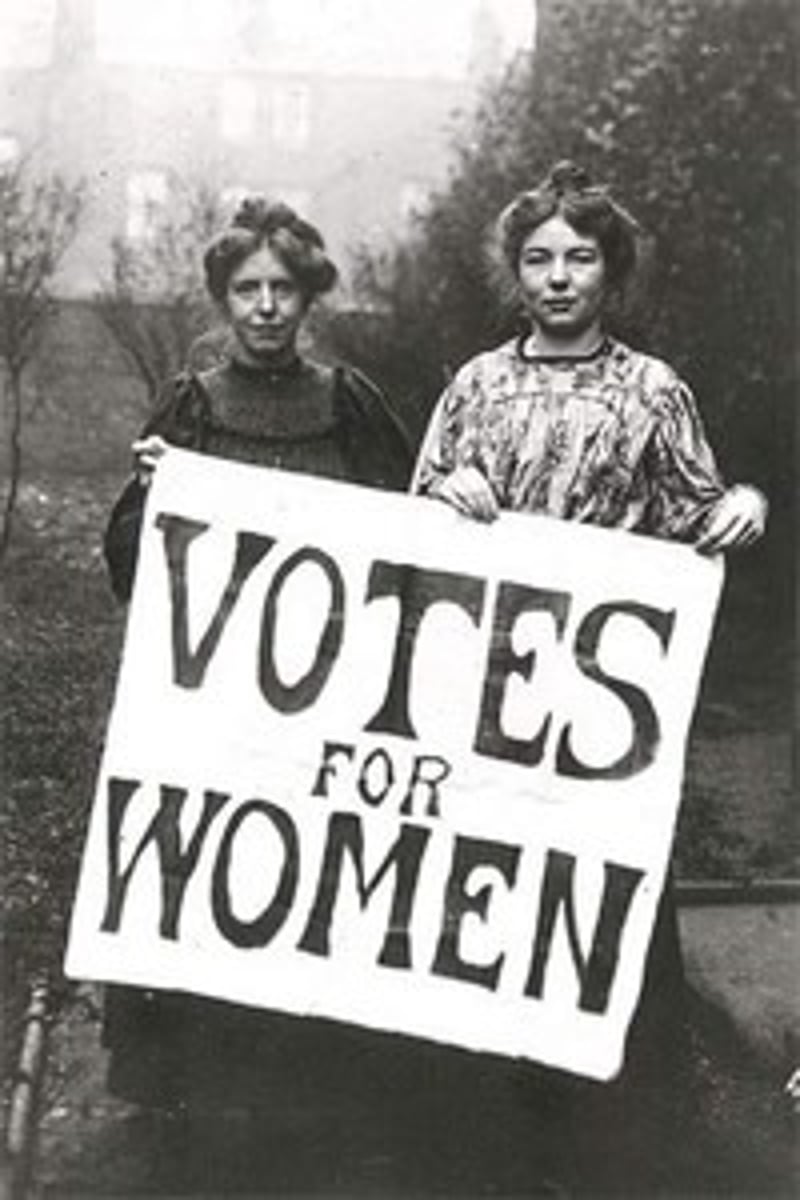

19th Amendment (woman suffrage), 1920

Extended the right to vote to women in federal or state elections.

Reforms to the democratic process: primary election, initiative, referendum, recall

During the Progressive Era, several states, including California under Hiram Johnson, adopted the initiative and referendum (the former allowed voters to propose legislation, the latter to vote directly on it) and the recall, by which officials could be removed from office by popular vote. The primary election allowed Parties to select candidates for office in a more democratic fashion.

Government by expert

In general, Progressives had faith in expertise; they believed that government could best exercise intelligent control over society through a democracy run by impartial experts who were in many respects unaccountable to the citizenry.

Jane Addams and Hull House

One of the Progressive era's most prominent female reformers, she founded this "settlement house" in Chicago in 1899, which was devoted to improving the lives of the immigrant poor. They built kindergartens and playgrounds for children, established employment bureaus and health clinics, and showed female victims of domestic abuse how to gain legal protection. By 1910, inspired by this model, more than 400 settlement houses had been established in cities throughout the country.

The Woman Suffrage Movement

Beginning in 1848, at the Seneca Falls Convention, and completing its mission in 1920 with the passage of the 19th Amendment, this movement aimed to give women the right to vote. Mostly a movement of white elites in the 1890s, after 1900 it engaged a broad coalition and became a mass movement for the first time.

Maternalist Reform

Arising from the conviction that the state had an obligation to protect women and children, female reformers during the Progressive Era called for government action to improve the living standards of poor mothers and children by enacting policies such as mothers' pensions (state aid to mothers of young children who lacked male support.) and laws limiting the hours of labor of female workers.

Muller v. Oregon, 1908

In this case, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld the constitutionality of an Oregon law that had set maximum working hours for women. Upholding this law ran counter to the Court's prevailing doctrine of liberty of contract (as expressed in Lochner v. New York, 1905) because the beneficiaries of the state regulation in this case were women. The Court's opinion solidified the view of women workers as weak, dependent, and incapable of enjoying the same economic rights as men. Afterwards, many states enacted maximum hours laws for female workers, and many women derived great benefit from these laws; however, other women saw them as an infringement on their freedom.

Workers compensation laws

Laws enacted to benefit workers, male or female, who are injured on the job. These laws reflected the concept of "economic citizenship," that government assistance derived from citizenship itself, not from some special service to the nation (as in the case of mothers) or upstanding character (which had long differentiated the "deserving" from the "undeserving" poor).

Minimum wage, maximum hours, and worker's compensation laws

Several of the main legislative goals of the labor movement during the Progressive Era. While nearly half the states enacted workers' compensation laws during the era, the dominant ideology of "liberty of contract" meant that very few state-level minimum wage and maximum hour laws were enacted, and those that were only applied to female workers (a result of the maternalist reform movement).

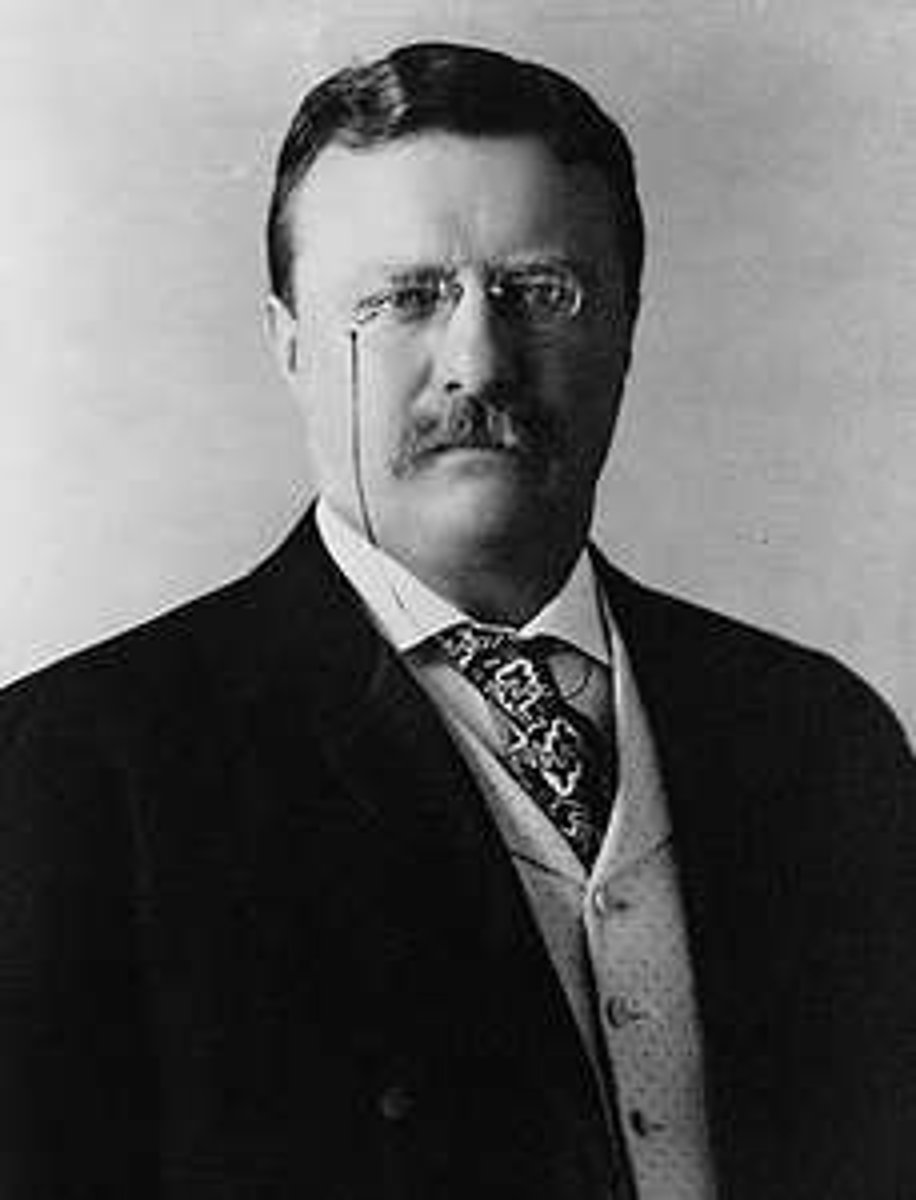

Theodore Roosevelt (TR) and the Square Deal, 1901-1909

The first of the three Progressive Era Presidents, and the term that refers to his legislative agenda while President.

The breakup of J.P. Morgan's Northern Securities, 1904

Teddy Roosevelt shocked the corporate world by announcing his intention to prosecute under the Sherman Antitrust Act the Northern Securities Company. Created by financier JP Morgan, this "holding company" owned the stock and directed the affairs of three major western railroads. It monopolized transportation between the Great Lakes and the Pacific. In 1904, the Supreme Court ordered Northern Securities dissolved, a major victory for the antitrust movement. This event symbolized the shift away from the pro-big business laissez faire policies of the Gilded Age.

TR and the 1902 Anthracite Coal Strike

This was one of the first moderate victories of the Labor Movement at the national level. Teddy Roosevelt believed that the president should be an "honest broker" in labor disputes rather than automatically siding with the employers as his predecessors had usually done under PBBLF. When a strike paralyzed the West Virginia and Pennsylvania coalfields in 1902 (which threatened a nationwide fuel shortage for stoves and fireplaces just as winter was approaching), he summoned union and management leaders to the White House. By threatening a federal takeover of the mines, he persuaded the owners to allow the dispute to be settled by a commission he himself would appoint. This did not give all workers a universal right to form unions, but TR's insistence that these employers negotiate with this union this time signaled a transition away from PBBLF and a shift towards the growing influence and power of organized labor.

Hepburn Act, 1906

Progressive Era law, signed by TR, that Imposed stricter control over railroads and expanded the powers of the Interstate Commerce Commission, including giving the ICC the power to set maximum rates, which was a significant step in the development of federal intervention in the corporate economy.

Pure Food and Drug Act, 1906

Progressive Era law, signed by TR, the first law to regulate manufacturing of food and medicines; prohibited dangerous additives and inaccurate labeling.

Meat Inspection Act, 1906

Progressive Era law, signed by TR, created largely in reaction to Upton Sinclair's The Jungle, the law set strict standards of cleanliness in the meatpacking industry.

John Muir, the Sierra Club, and Hetch Hetchy

Scottish-American preservationist (keep wilderness wild) who founded the first organization devoted to environmental preservation in 1892 to help preserve forests in their "natural" state by making them off limits to logging by timber companies. His love of nature stemmed from deep religious feelings; he believed people could experience God's presence directly through nature. A proposal to dam Hetch Hetchy Valley (a beautiful valley just north of Yosemite Valley in California) to provide water for the city of San Francisco lead to the first great environmental political battle in U.S. history between Sierra Club preservationists (opposed to building the dam) and "wise-use" conservationists resource managers who supported the dam. Muir and the Sierra Club lost the debate, and the dam was built.

The National Park Service

The United States led the entire world in environmental preservation by setting aside great areas of land for wilderness preservation, personal growth, and recreation, rather than for resource extraction or agriculture. In 1916, this service was created to manage all the National Parks. In contrast to this system, the National Forest system applies the philosophy of conservation ("wise use") by allowing regulated resource extraction from National Forests. (Chadwick's Outdoor Ed programs usually take place in National Forests or in Joshua Tree National Park)

The Conservation Movement

This movement proposes "wise use" of natural resources at a sustainable rate, and it is applied by the National Forest System. This is different from the closely related philosophy of "preservationism," which refers to keeping natural areas "wild" and entirely off limits to human development. Both these movements took off during the Presidency of Teddy Roosevelt, who created the U.S. Forests Service and ordered millions of acres of land to be set aside as wildlife preserves and encouraged Congress to create new national parks and forests. This is one of many examples of how the federal government became increasingly involved in regulating the economy during the Progressive Era.

William Howard Taft and "trust-busting"

The second Progressive Era President, he pursued antitrust policy even more aggressively than TR. He persuaded the Supreme Court in 1911 to declare John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil Company in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act and to order its breakup into separate marketing, producing, and refining companies.

The Election of 1912

The four-way contest between Taft, Roosevelt, Wilson, and Debs became a national debate on the relationship between political and economic freedom in the age of big business. Taft stressed that economic individualism could remain the foundation of the social order so long as government and private entrepreneurs cooperated in addressing social ills. Debs emphasized abolishing the capitalist system and also demanded including public ownership of the railroads and banking system, government aid to the unemployed, and laws establishing shorter working hours and a minimum wage. However, it was the battle between Wilson's New Freedom and Roosevelt's New Nationalism over the role of federal government in securing economic freedom that most galvanized public attention. In the end, Wilson was elected.

Woodrow Wilson

Third Progressive Era President of the United States; academic and progressive Democrat who was elected President of the United States in 1912 and again in 1916; his first term was concerned with domestic progressive reforms, but his second term was caught up in World War I and his efforts on behalf of the Versailles Treaty.