Art History I Exam Other Artists

1/25

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

26 Terms

Etruscan artists excelled in the art of modeling and firing large-scale clay sculptures, partly because of the lack of stone suitable for sculp- ture in Etruria. In addition to decorative antefixes and revetments, life-sized akroteria sculptures identified as gods, goddesses, and heroes were located on the roof of the Temple of Mnerva at Veii, along the ridge. These dynamic figures were made of terra-cotta and brightly painted. Perhaps the best-known surviving example is a statue of Apulu (Greek Apollo), which formed part of a group acting out a scene from Greek mythology, the third labor of Herakles.

Its strategic position on important trade routes made it a crossroads of cultures from early times. It is therefore not surprising that its art and architecture effectively blend diverse styles to create a distinctively Roman aesthetic.

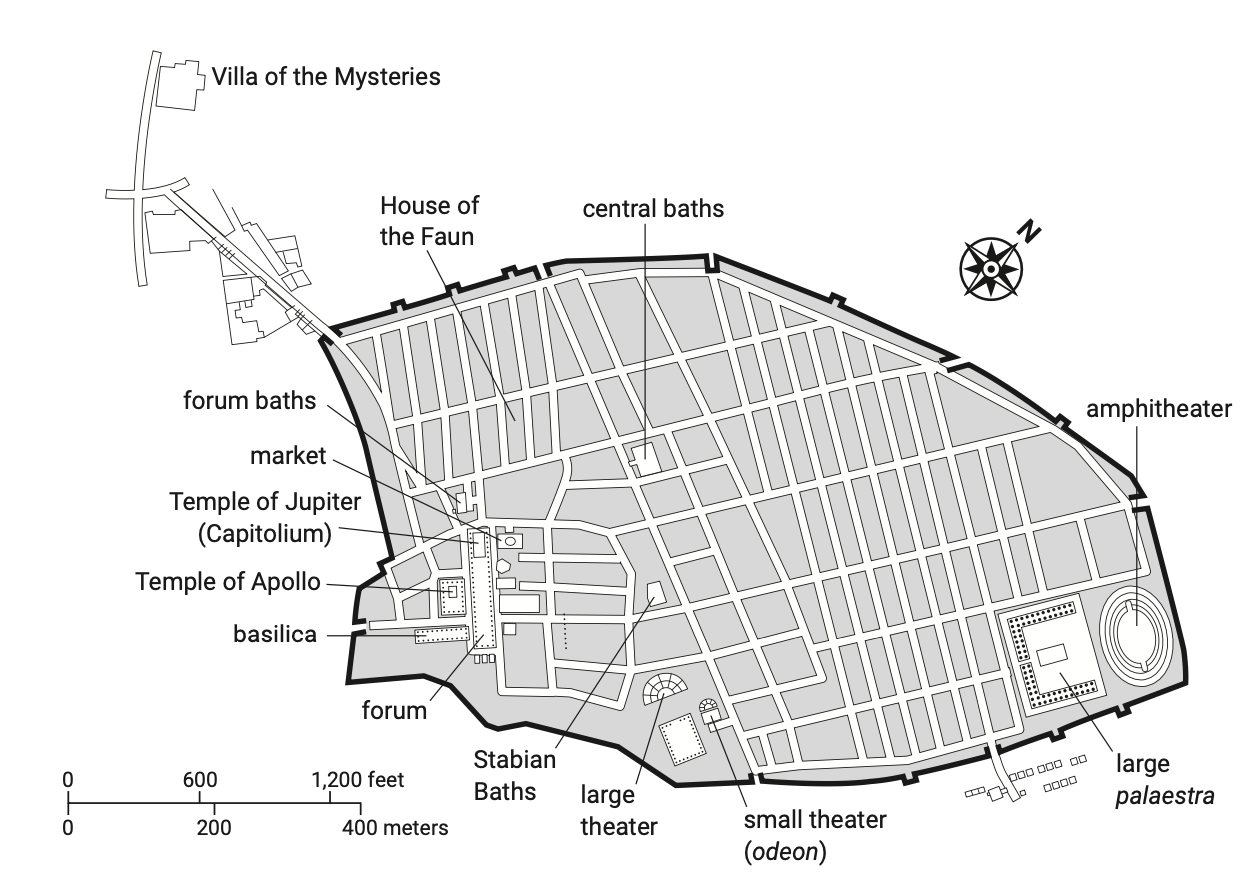

In 79 ce, a volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius buried Pompeii, preserving streets, businesses, houses, and public buildings. (The city was rediscovered and exca- vations commenced in the mid-eighteenth century.)

an open air, polychrome, marble altar that is oriented to the cardinal points .The senate commis- sioned this public monument in 13 bce to commemorate Augustus’s return to Rome after military campaigns in Hispania and Gallia (present-day Spain and France). It was dedicated on Livia’s birthday in 9 bce in the Campus Martius (Field of Mars, the god of war) on the route by which Augustus would have entered Rome on his triumphant return.

built to commemorate his victorious Dacian campaigns, is an example of the narrative art that Trajan used for propaganda purposes. Located just beyond the Basilica Ulpia, it also served to indicate the height of the hill that Trajan removed in order to build the forum, a feat he considered impressive enough to document in the inscription on the column’s base. The column is made of hollow marble drums placed on top of one another. The square base below the column, which became a mausoleum for Trajan and his wife Plotina after their ashes were placed there, was covered with sculptures of Dacian arms and armor. The very top of the column held a bronze statue of Trajan, though a later statue of St. Peter (1588) now occupies that position.

Following the empire’s division into parts, the tetrarchs worked diligently to convey a message of unity and joint power, focusing on the office rather than the individuals holding the posi- tions. Earlier portraits of Roman rulers emphasized their individual features and sometimes even their person- alities. In the Portraits of the Tetrarchs (Fig. 22.8)—two sculptures put together, each depicting an Augustus and a Caesar in a tight embrace— generality and abstraction replace individuality and naturalism. The sculptures were carved in porphyry, a hard, purple stone from Egypt reserved for sculptures of the imperial family and the gods. There are no distinctions between the rulers in terms of facial features, stature, dress, and gesture, with the exception of the beards worn by the Augusti to demon- strate their more advanced age (the bearded Augusti are on the left of each pair; see also p. 364). Their bodies are squat, and there is no interest in revealing the structure of the body underneath the military dress, which is carved in schematic patterns. Wearing the cuirass and cloak of the military general, each figure grasps the hilt of a jew- el-inlaid, eagle-headed sword. The emphasis here is the concordia, or harmony, of the tetrarchs at the expense of their individuality. The chaos of the previous period of the soldier emperors had made it clear to the four co-rulers that the impression of unity was essential; much was at stake, including their lives.

Early Christian imagery was uncommon in sculpture before the Edict of Milan. Nonetheless, a few rare, portable marble carvings, com- missioned by wealthy patrons, survive and reveal the persistence of Classicism. Chief among them is a cache from Phrygia in central Anatolia (present-day Turkey) that contained this third-century ce marble sculpture of the Good Shepherd (Fig. 23.7). Early Christians incorporated stylistic motifs from ancient sources, simultaneously developing new imagery and iconography to depict their religious narratives and convey their teachings. With a facial type popular in early Christian representations, this young, handsome, and beardless Christ resembles the Greek god Apollo rather than the later convention of a more mature Jesus with a beard. As in the painting in the Dura-Europos baptistery (see Fig 23.5), the shepherd carries the sheep across his shoulders.

In the Catacomb of Saints Peter and Marcellinus outside of Rome, named after two third-century ce martyr-saints, the vault of a cubiculum was covered with frescoes (Fig. 23.8, p. 384). The composition’s layout and the simplified, sketch-like style of the imagery are not unique to Christianity. In fact, they are similar to art found in catacombs of other groups, suggesting that artist workshops did not serve the needs of only one religion. At the center of the painted ceiling, a medal- lion represents Christ as the Good Shepherd. He stands with one knee slightly bent, surrounded by sheep that might represent the Christian flock. The circular space outlined in red is surrounded by four lunettes depicting the Old Testament story of Jonah. On the viewer’s right, Jonah, having spent three days in the belly of a whale, is an exultant living figure cast out of the sea-creature’s mouth. Jonah’s prefiguration of Christ’s death and resur- rection is a fitting design for the catacombs, as it depicts how the dead, like Jonah and Christ, will be reborn in heaven. In response to his release, Jonah extends his arms. This prayerful gesture or orant is repeated by four figures placed between the outlined lunettes.

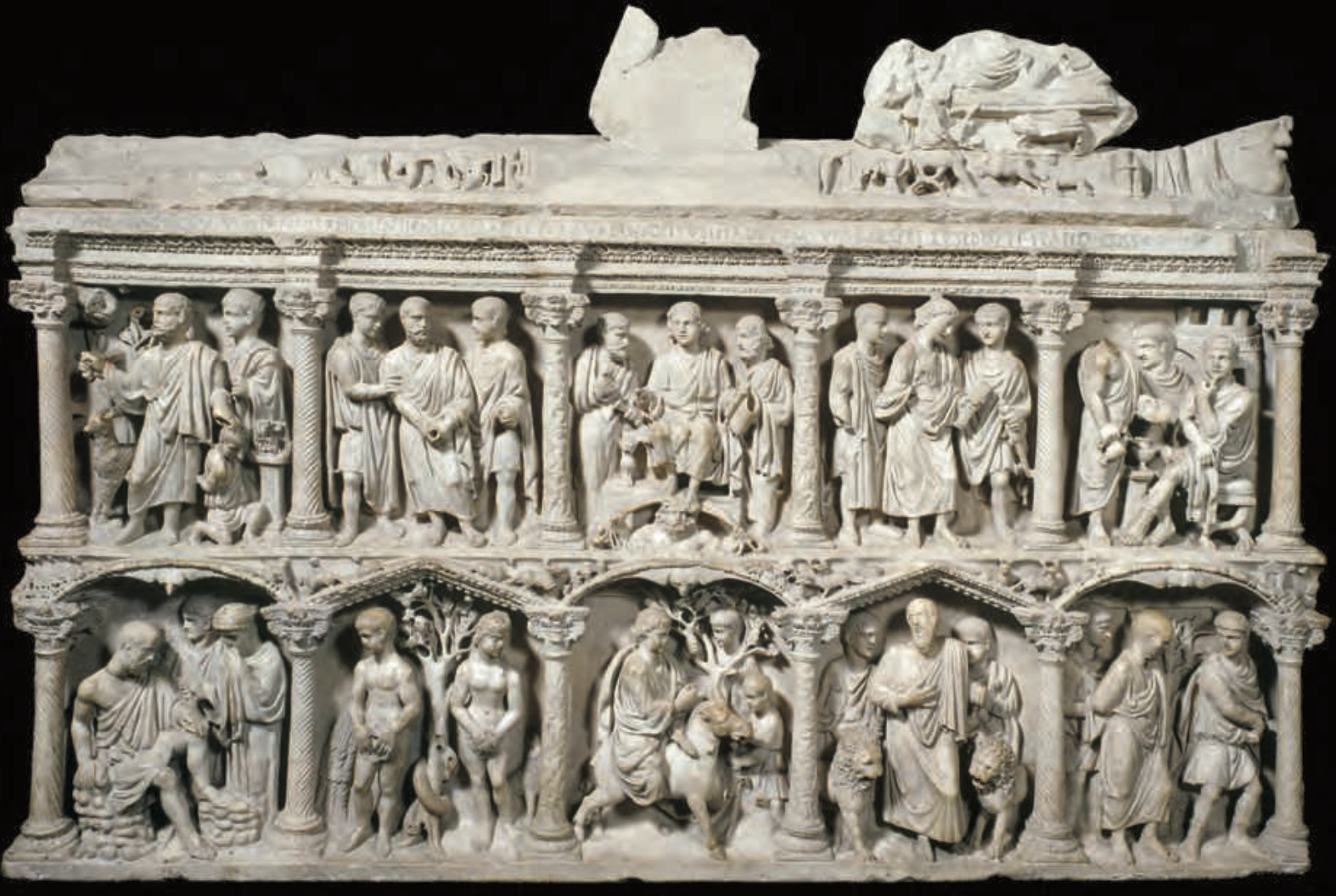

The closest sculptural analogy to the huge frescoes and mosaic cycles in public church interiors comes from Roman carved sarcophagi, newly adapted to Christianity after Constantine and Licinius declared Christianity legal. The relief carvings on the sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, a Roman prefect (magistrate), begin to present a specifically Christian art, even though the overall visual appearance of this sarcophagus from St. Peter’s Basilica remains explicitly Classical (Fig. 23.10).

The use of a marble coffin for an elite burial, and the carving in high relief, are both quite conventional. The carved reliefs present a variety of narratives in two horizontal registers. This surface uses spiraled columns and niche spaces to frame and isolate scenes, which are filled with carefully carved, well-proportioned figures. What makes the Bassus sarcophagus different from Classical examples is its subject matter, not its style. In the upper central panel, enthroned and frontal, a youth- ful and beardless Christ sits dispensing law like a Roman emperor. He is seated higher than the flanking figures of Peter and Paul.

including vine scrolls and putti, derive from the bacchanals of other religions and are similar to those used in secular spaces. The trampling of grapes, readily associated with

the Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, also has conno- tations of the Eucharist, a Christian sacrament. In the center of this mosaic segment (Fig. 23.19), the vines coil around in a circle, creating a framing device for a portrait bust of a woman. She is believed to be Costanza herself, portrayed in a manner similar to the goddess Juno or a Roman matron. Originally the central space contained mosaics with scenes of the Elysian Fields, the ancient Greek paradise. As befits the Christian doctrine of resur- rection, both the ornate setting and the mosaic subjects suggest joyous celebration.

Like Constantina’s mausoleum, martyria are typically central-plan designs. Sacred relics are often located in the middle of the floor plan, giving viewers the oppor- tunity to circumnavigate the presence of the sacred as they remember a specific holy person. For later Christian buildings, the spiritual rebirth conveyed by baptism dic- tated similar round structures, especially when these baptisteries were built adjacent to basilica churches. The similarity between baptisteries and martyria makes sense; both types of buildings mark the death of the old self and celebrate life anew.

The minbar, the oldest in existence, is made of teakwood, which comes from the island of Java in Southeast Asia (Fig. 24.17a, p. 410). It uses a frame construction into which smaller rec- tangular panels are set. Those panels, which probably were carved in Iraq and assembled on site, feature the same abstract, plant-inspired, geometric patterning as Samarra’s stuccowork. The concave portion of the mihrab contains rectangular marble panels that probably were carved locally, as they alternate between Samarra Style designs and Roman-inspired seashell motifs. The top of the mihrab and the wall behind it are decorated with lusterware tiles, which must have been expensive and thus were spread out in a pattern for maximum effect. Written sources suggest the tiles were sent, along with a master craftsman, by the central government in Baghdad. These newly developed luster tiles would have sparkled in the light of the candelabras and drawn worshipers’ attention to the qibla wall, expressing the power of God and the power of the caliphate simultaneously.

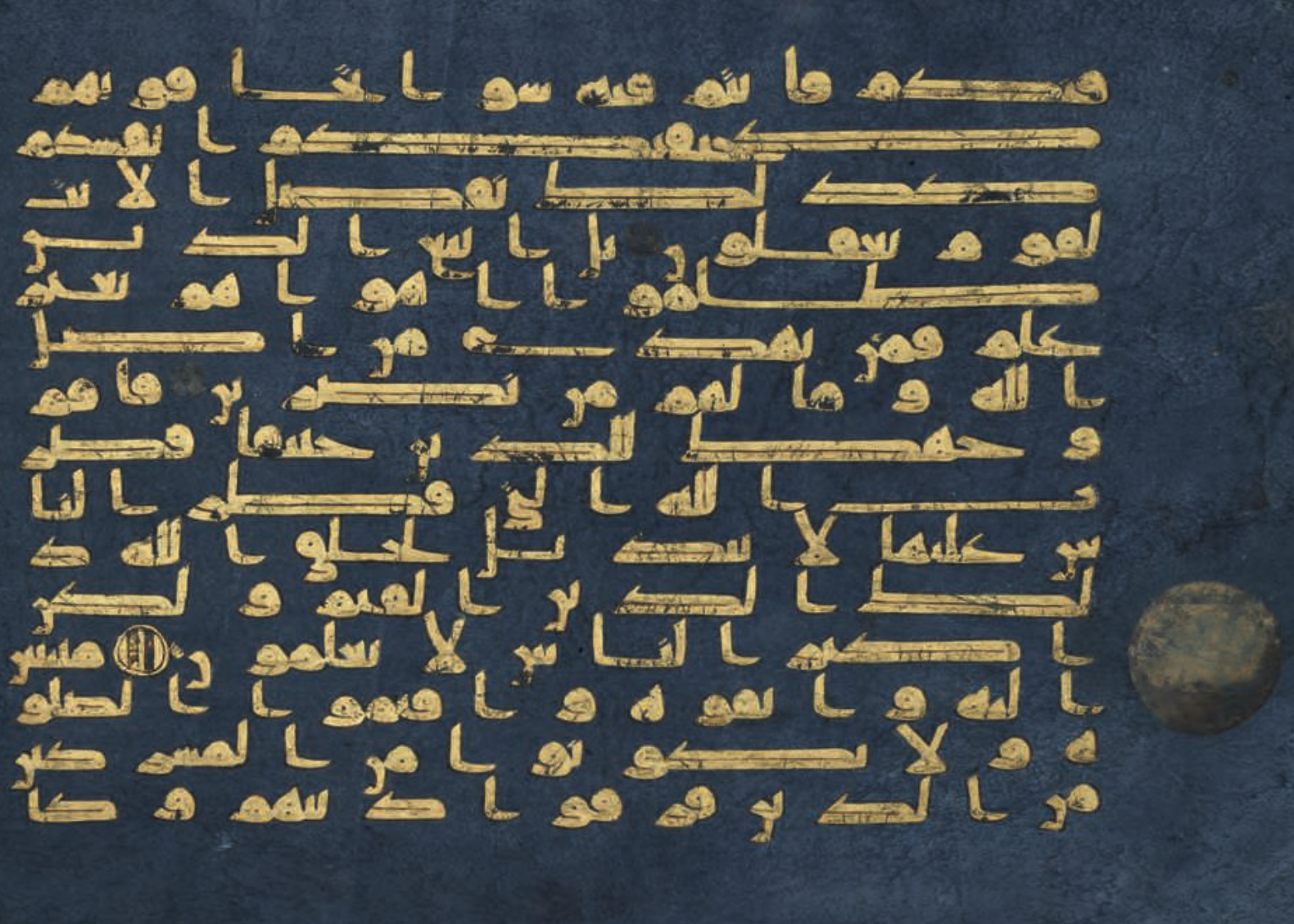

The Blue Qur’an takes its name from the brilliant blue of its indigo-dyed parchment pages. Notably, rather than reserving gold solely for chapter headings or other special features, as earlier luxury Umayyad Qur’ans did, here the entire text is written in the precious metal. The lines have been copied so that each one is exactly the same width on the page, adding to the graphic impact of the gold against blue. (For more on the artistic potential of the Arabic script, see: Seeing Connections: The Art of Writing, p. 560.) The only ornamentation, apart from the rich coloring, is the occasional silver circle (now faded and tarnished) in the margins, each indicating a new chapter. Notice the complete lack of diacritical marks.parchment a writing surface prepared from the skin of certain animals that has been treated, stretched, and polished.

Great Zimbabwe enclosure, On the shelf-like platform, archaeologists found miniature stone dishes and small statues, similar to the sculpture in mud and wood that was displayed in the twentieth century to girls in southern Africa when they were being prepared for adulthood. (In Venda communities, for example, older women manipulated such figures like puppets, acting out stories and morality plays to teach the girls about social relationships and sexual behavior.)

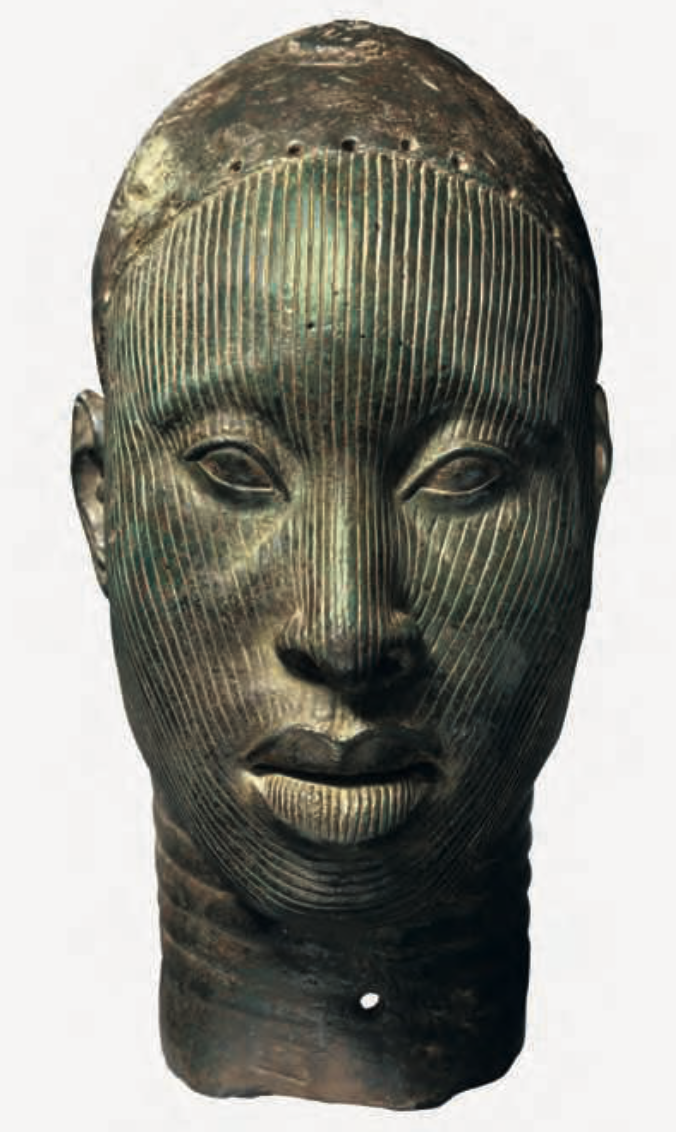

A group of over a dozen of the life- like heads of Ile-Ife were unearthed in the household of the Wunmonije family, near the palace of the Oni. Shown as neither very young nor very old, all of the heads in this group appear serene, and are life-sized. Early Yoruba met- alsmiths sculpted the heads in brass or in other copper alloys using a technique known as lost-wax casting (see box: Making It Real: Lost-Wax Casting Techniques for Copper Alloys, p. 62). At least four centuries earlier, the same technique had been employed to cast bronze regalia for a leader of the Igbo people at the site of Igbo-Ukwu, about 250 miles to the southeast (Figs. 2.16 and 2.17).

Analyses of fragments of the clay core left within one of these copper heads (Fig. 25.16) broadly date it as made between 1215 and 1575, but some scholars argue that all of the heads were made around 1300.

Perforations around the hairline have retained strands of thread that might have tied a beaded crown onto the head. Some art historians believe that these sculptures protected and displayed the crowns of the Oni and his ancestors, possibly during coronation rituals in Ile-Ife. As Yoruba crowns and other beaded items of regalia are seen as highly sacred today, they would have needed to be kept safe in the past as well, especially in times of transition.

Modern Yoruba rulers own beaded, often conical crowns with strings of beads that veil their faces, and some observers have interpreted the fine lines covering the face of this portrait (and the faces of some of the other heads in terra-cotta and copper alloy) as a type of veil. Others interpret the lines as scarification similar to the ichi marks of status worn by the Igbo, as seen in very early sculptures (see Fig. 2.19). In the case of Ile-Ife, these parallel lines might have shown that leaders belonged to specific lineages or dynasties, or they may simply be an aesthetic device used to reflect the light in a subtle, unusual way.

The resulting vast open space was the largest vaulted structure in the world before the con‐ struction of the new St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome in the sixteenth century (see Fig. 45.12).

In contrast to the ancient Roman Pantheon (see Fig. 20.13), built of concrete and faced with marble bricks, the Hagia Sophia was built with masonry construction. In addition, the Byzantine church’s magnificent central dome, more than 100 feet (30 m) in diameter, does not rest atop cylinder walls. Rather, it is carried on four enormous arches that rest upon corner piers on a square ground plan.

This icon of the Virgin and Child (Fig. 28.12), made for St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai in Egypt (c. 700), is a rare survivor of later iconoclasm. The monastery’s remote location allowed the icon to escape destruction at the hands of Byzantine image‐breakers. In this work, the seated Virgin Theotokos (meaning “Bearer of God”) and her son are shown frontally, positioned in hierarchy. They are flanked by two warrior‐saints, Theodore and George, who gaze intensely at viewers. Behind them, two angels strain their necks, directing onlookers’ vision to the heavens, as a centrally placed hand of God offers a blessing. The icon is quite crowded, discouraging devotees’ eyes from wandering and encour‐ aging the faithful to discover the means of their salvation.

Another Middle Byzantine cross‐in‐square structure is the monastic Church of the Dormition (the “falling asleep” or death of Mary), which may have been commissioned by the emperor Basil II (ruled 976–1025). It is located in Daphni, site of an ancient laurel grove near Athens. Unfortunately, the building was sacked by Frankish crusaders in 1205, and it has been severely damaged by earthquakes. Nonetheless, a dramatic mosaic of the Pantocrator survives in its cupola (Fig. 28.19). Unlike the Apollonian image of a beardless, youthful Christ found at San Vitale (see Fig. 28.7), the Daphni Pantocrator looks quite stern, readily to admonish beholders. This Christ has a cruciform (cross‐shaped) halo and grips sacred scriptures in his left hand. The deep shadows around his eyes and the heavy linearity of the image seem to confront beholders, demanding to know whether they are contrite and properly prepared to enter heaven.

Insular art often brought together different artistic traditions – Celtic, Germanic, and Roman. Like many other Insular manuscripts, the Lindisfarne Gospels include carpet pages filled entirely with ornamentation. These pages were not merely abstract decorations separating texts: making and viewing these vibrant designs served as aids to religious meditation, fostering greater participation in the myster- ies of the faith. An active perusal of the dynamic imagery was believed to animate the soul of both the artisan and the beholder. On this page, a large cross symbol extends across the entire energetic pattern of looping, intertwined spirals formed of elongated bird-like creatures rendered in four colors (Fig. 29.4). This page combines Germanic use of animal ornament with the ribbon interlace rooted in Roman culture. Within this, the cross appears to be static, unmoved by the effects of time. In contrast to the rhythmic interplay of twists and turns, the stationary cross relates to the Christian belief that Christ is eterna

The most dazzling of the Insular man- uscripts, the Book of Kells (c. 800 ce) incorporates its interlaced intricacies into the opening initials of the Gospel of Matthew (Fig. 29.5). Using X-P-I (Chi-Rho-Iota), the first three letters of the word Christ in Greek, and then continuing in the lower-right corner with the Latin (Roman) word generatio, this lettering begins the text that specifies the genealogy of Jesus. Amid its whirling triskeles and loops, the fine network of lines includes subtle imagery of animals: a mouse, cats, moths, and an otter catching a fish. The head of a human appears at the end of the Rho, and angels are visible along the length of the Chi. Like the Book of Durrow, the Book of Kells was protected in a metal container and treated as a holy item. In the Annals of Ulster, recorded in 1007, it is called “the most precious object of the western world.” It was probably produced in the scriptorium (room used for writing) of the monastery on the Scottish island of Iona, and it may have been brought to the monastery of Kells in Ireland after a series of Scandinavian attacks. From the late eighth century, the British Isles were beset by Scandinavian invasions along their eastern coasts and riverways, including attacks on Lindisfarne in 793.

Bishop Bernward’s other Hildesheim masterwork is a giant pair of bronze doors, probably originally placed on the church’s south- western side (Fig. 29.20). The doors feature figures in high relief gesturing dramatically against flat grounds with outlined details of their setting. The bishop’s commission may have been inspired by his visit to Rome, where he would have encountered decorated wooden doors at churches such as Santa Sabina (see Fig. 23.17). Casting bronze works of such grandeur, including the lion’s head handles, was an extraordinary technical achievement.

Bernward probably played a significant advisory role in determining the complex iconographical program of the doors (Fig. 29.19), which pair scenes from the biblical Book of Genesis with their gospel counterparts.

Painted by the otherwise unknown court artist Zhang Zeduan, Peace Reigns along the River begins with rural scenes in the early morning. The painting is designed to be viewed by a single person or a small group seated at a table. At their own pace and with their own hands, viewers unroll the handscroll from right to left. They see a river appear and carve a path toward increasingly populated areas. Taking advantage of the sequential viewing process, Zhang structures his composition as a journey along the river. The anticipation of seeing what is concealed in the scroll reaches a climax in the scene of the rainbow bridge reproduced here (Fig. 31.5). Gathering on the bridge, which is already crowded with vendors, spectators watch a frantic crew trying to lower the mast and safely guide their boat beneath the bridge. Someone has thrown a coiled rope to the sailors; onlook- ers gawk at the unfolding drama. On the other side of the bridge, the prow of another boat emerges, foreshad- owing a safe outcome. Following the river to the left, viewers eventually encounter a road leading to a city gate and the scroll’s conclusion within the bustling city (not pictured here).

The fan-painting format (see Fig. 31.2d) also makes a useful object during the warm, humid summers of Lin’an.

Li’s painting is a tour de force. On the tree, just above and to the right of where the bamboo stalk meets it, Li has written in minute characters, “three hundred items.” Enticed by the peddler’s racks, which are crowded with tools, medicines, edibles, and toys, one child clambers onto the base the better to extend his reach. His pals are close behind, and even the suck- ling baby dangles a hand toward the tower of delights. The peddler wears a necklace featuring three round disks decorated with human eyes. This type of necklace was worn by eye doctors, but in this picture, it signals one of the painting’s themes, vision. For the children, vision leads to material desire; seeing boisterous poten- tial customers, the peddler must take action. For the viewer, the sheer abundance of objects in so small a painting becomes an amusing challenge to the limits of vision. At the far right, one stealthy child has eluded the peddler’s sight and may sneak away with a modest treasure in hand.

There is a standard iconography that allows viewers to identify forms of the Buddha and bodhisattvas (see Chapter 16). All bodhisattvas wear jewelry, but the tiny Amitabha Buddha figure in the crown identifies this figure specifically as Guanyin. Formed of multi- ple pieces of willow wood, the figure of Guanyin assumes a relaxed posture of royal ease, seated with its right arm resting on a raised knee. This pose further indicates a particular manifestation, the Water-Moon Guanyin, who presides over an island Pure Land, Mount Potalaka. (compare to Amitabha Buddha who presides over the Western Pure Land, see Figs. 27.12 and 27.17). Naturalism in the representation of Guanyin’s face, body, and drapery continues the direction of Tang International Style

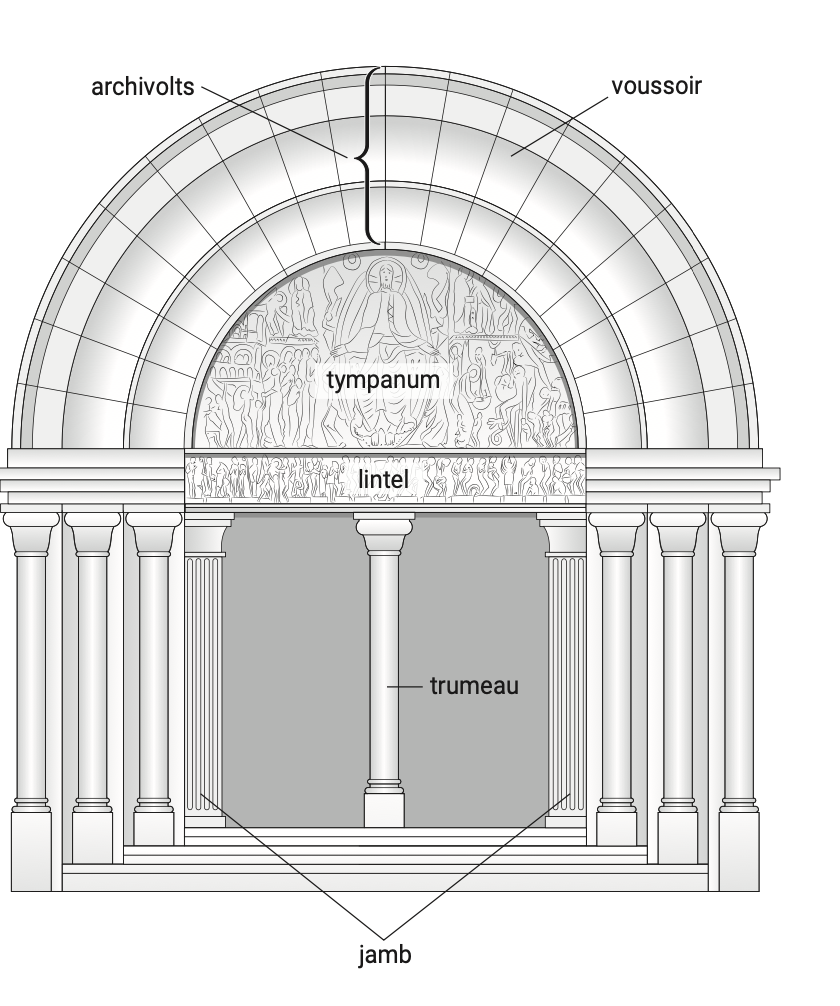

A Romanesque church portal typically consists of a rounded arch that rests above a set of supporting columns, called jambs, which were sometimes adorned with column figures and related sculptures (Fig. 35.6). The arch itself is composed of molded archivolts, and like arches, they have wedge-shaped segments called voussoirs. In some Romanesque churches, the archivolts were adorned with designs, including figurative or deco- rative motifs, to fill out or complement the major scene of the tympanum—an architectural feature popularized in the Romanesque era—which is the sizable semicircular surface between the arch and the lintel of the doorway. The high, central placement of the tympanum makes it a favored space for reliefs, particularly groupings of many figures, such as the Last Judgment, in which, according to Christian belief, the dead are either admitted to heaven or condemned to hell. Beneath the lintel, separating the doorway openings, is a central stone pier, called the trumeau, often adorned with a major sculpted figure such as Christ or the Virgin and Child.

live in preparation for death. The trumeau is decorated with images of the church’s patron saint, Lazarus, who is said to have died and been brought back to life by Jesus. Lazarus is flanked by his sisters, Martha and Mary Magdalene.

Above the door, the tympanum depicting the Last Judgment greets approaching worshipers. The haloed Christ appears in the middle with his palms open, indi- cating the gift of salvation. The Good Shepherd of early Christian depictions of Jesus (see Chapter 23) is replaced by a king in majesty on the throne of heaven. He is placed within a mandorla surrounded by trumpeting angels, who proclaim his triumphal return and summon the recently awakened dead to be judged. The outer edges of the almond-shaped cloud bear a Latin inscription, “I alone dispose of all things and crown the just; those who follow crime I judge and punish.” On the lintel below the tympanum, the dead rise from their graves, waiting to hear their eternal fate. Directly below Christ’s feet, a Latin inscription reads, “Gislebertus made this.” This inscription may indicate the artist in charge of a work- shop, or it may refer to a donor responsible for bringing the sacred relics of Lazarus to Autun.

this sculpture originally served as a liturgical object, placed on a church altar in Auvergne, France (Fig. 35.12). In addition, it was likely carried in religious processions. The Virgin Mary and Christ child are shown enthroned in rigid frontality, affirming their regal status. The freestanding wooden sculpture is poly- chrome; the use of naturalistic color is still apparent on the figures’ faces, and traces of red and blue paint can be seen on the Madonna’s robe. The folds of her garment are regular in their repeated arcs, creating a rhythmic pattern. The sculpture has been damaged over time, and Christ’s hands and arms are now missing. He probably held the Gospel in his left hand and made a gesture of blessing with his right.