BM422 - Block B (cell death mechanisms)

1/86

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

87 Terms

what are the two mechanisms of cell death?

apoptosis (controlled cell death)

---

necrosis (uncontrolled cell death)

are necrosis and apoptosis independent or co-dependent?

they are completely independent/separate BUT can be observed simultaneously

what is the purpose of apoptosis?

targets cells that are no longer required or that are damaged/infected

---

protective response

---

regularly occurring

with regards to apoptosis, what is the main differentiating factor from necrosis?

there is no injury to surrounding healthy tissue

---

(apoptotic debris is consumed by macrophages)

why/when does apoptosis occur?

in response to...

---

DNA damage

---

cellular stress

---

infection

---

developmental signals (during embryogenesis)

---

external signals (i.e., from immune cells (reduced expression/absence of MHC I))

what does apoptosis involve?

the cell will shrink, condensing the nucleus

>>>

the nucleus will then fragment

>>>

the cell then breaks apart into apoptotic bodies (i.e., small membrane-bound vesicles containing parts of the cell's contents)

---

apoptotic bodies are identified for rapid phagocytosis via exposure of PS and other "eat me" signals

how is apoptosis able to avoid damaging neighbouring cells?

formation of apoptotic bodies as opposed to just leakage of cell contents

what are some examples of apoptosis-associated receptors and ligands?

TNFR1 (on immune cell) and TNFalpha (on apoptotic cell)

---

Fas (CD95/APO-1) (on immune cell) and FasL (CD95L/APO-1L) (on apoptotic cell)

what is necrosis?

premature death of a cell or group of cells

what causes necrosis?

external factors (e.g., infection or trauma)

in summary, how does necrosis differ from apoptosis?

it is not regulated in the same way

---

uncontrolled release of cellular products >>> collateral damage to adjacent cells/widespread tissue damage

---

debris created is not recognised by immune cells >>> damage to adjacent cells

what is required for necrosis that is not required for apoptosis? (hint: external perspective)

medical intervention (it cannot naturally stop)

what are the five outcomes of cellular injury from least consequential to most consequential?

1. reversible injury (restoring cell function)

---

irreversible:

---

2. morphological changes

3. light microscopic changes

4. ultrastructural changes

5. cell death

what three methods can be used to visualise morphological consequences of cellular injury?

naked eye/cross examination

---

light microscopy

---

electron microscopy

with reference to injury, how do apoptosis and necrosis differ?

apoptosis is not necessarily associated with injury

---

necrosis is associated with progressive/irreversible injury

in summary, what is apoptosis?

cellular fragmentation with formation of apoptotic bodies >>> phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and fragments

in summary, what is necrosis?

breakdown of plasma membrane, organelles, and nucleus >>> leakage of contents

in terms of nuclear morphology, what are the three possible outcomes of necrosis? (i.e., hints that necrosis will occur/is occurring) (progressive stages of nuclear dissolution)

pyknosis (shrinkage/condensation)

---

karyorrhexis (fragmentation)

---

karyolysis (fading/dissolving)

what is pyknosis?

first stage of nuclear dissolution: nuclear shrinkage where DNA condenses into basophilic mass

what is karyorrhexis?

second stage of nuclear dissolution: nuclear fragmentation as a result of pyknotic nuclei membrane rupture

what is karyolysis?

third stage of nuclear dissolution: nuclear fading as a result of chromatin dissolution due to action of DNA/RNAases

what are the ultimate outcomes of karyolysis, karyorrhexis, and pyknosis?

anuclear necrotic cells

is nuclear dissolution always a progressive process? (do all three phases occur)

not always - usually nuclear morphology does progress through each stage but they do not all need to occur for necrosis

in terms of cytoplasmic morphology, what indicates the onset of necrosis?

it would appear a darker shade of pink (=eosinophilic) as the ribosomes dissolve

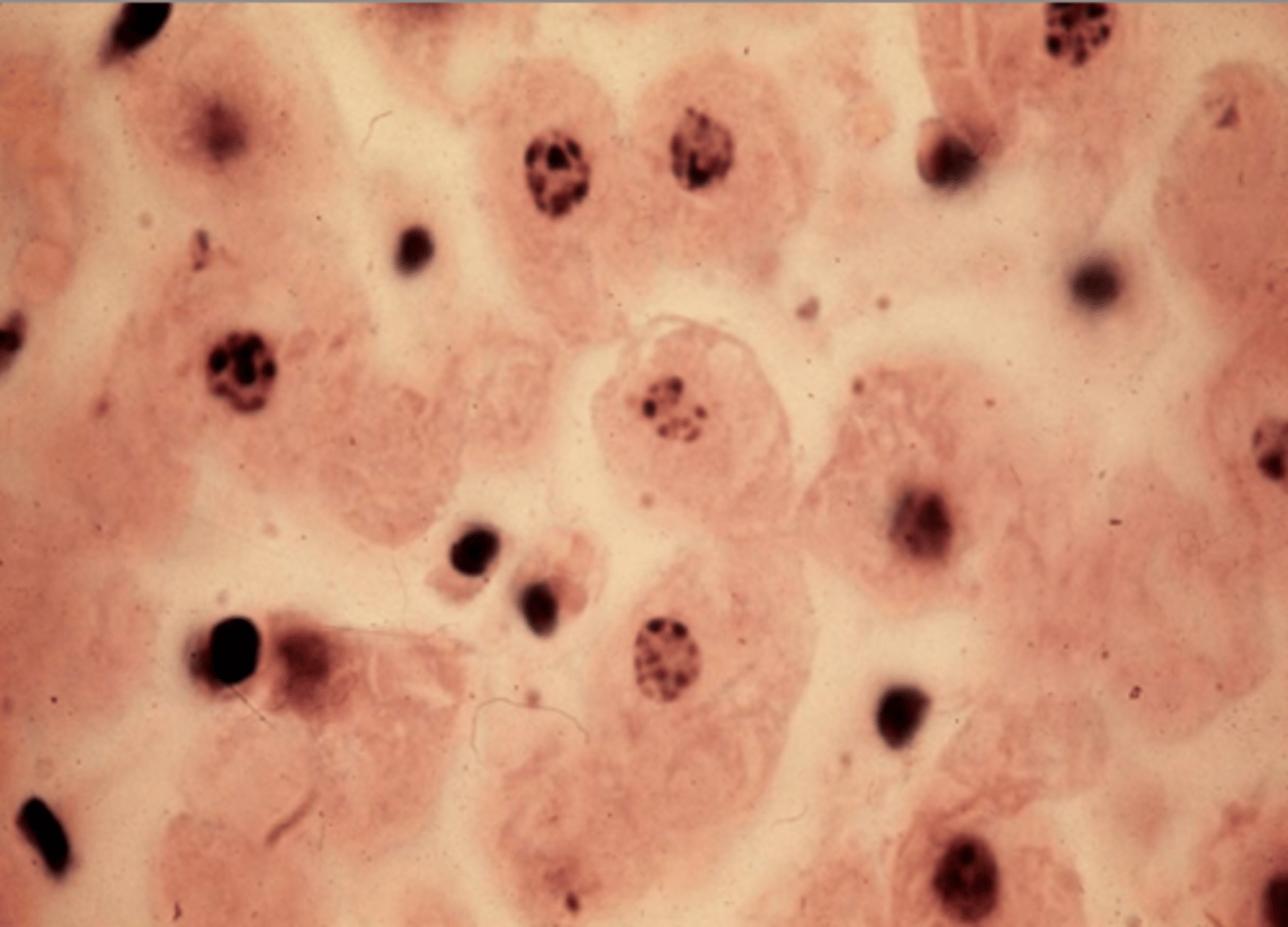

[visual] morphological indications of necrosis

-

what is the manifestation (appearance) of necrosis dependent on?

the type of tissue that the cell belongs to (e.g., heart, brain, etc.)

---

the type of injury that occurs

what are the 5 manifestations of necrosis?

1. coagulative

2. liquefactive

3. caseous

4. gangrenous

5. fat necrosis

in what type of tissue does coagulative necrosis occur? what type of injury is primarily associated with coagulative necrosis?

in firm tissues (primarily heart, kidney, spleen)

---

usually due to ischemia/infarction (=death due to ischemia)

what microscopic observations would be apparent in coagulative necrosis?

basic outline of dead cells would be preserved

---

dead tissue would retain its firm texture (denaturation of structural proteins >>> they coagulate/solidify (like how an egg would cook))

what is a myocardial infarction?

blockage in coronary artery (thrombosis) and/or loss of blood supply (oxygen) to heart muscle >>> myocardial infarction (heart attack)

what are the clinical manifestations of myocardial infarction?

severe chest pain and nausea (and more...)

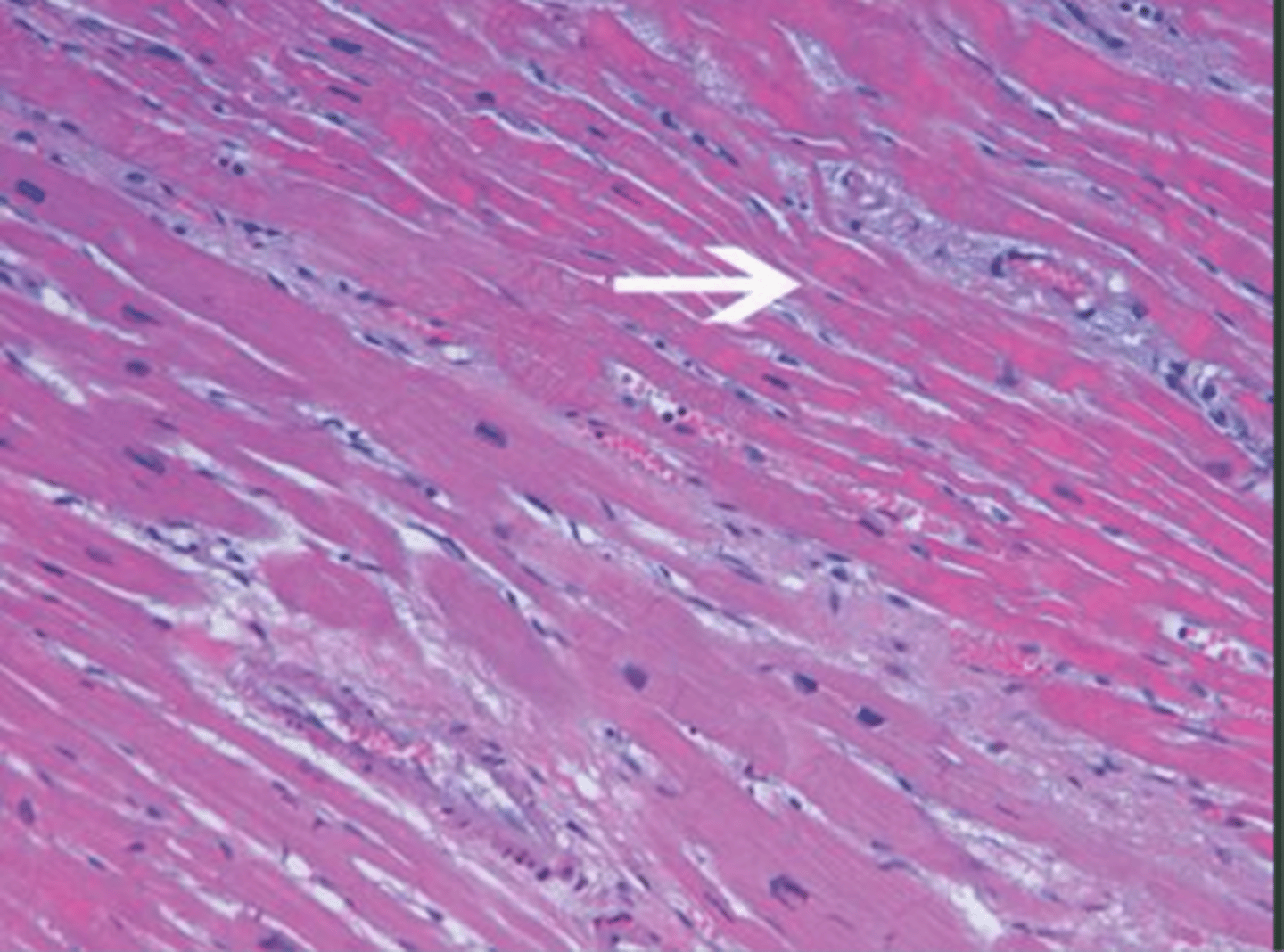

what microscopic comparisons can be made between a normal myocardium, early myocardial infarction (ischemia/inflammation), and later stage myocardial infarction (coagulative necrosis/inflammation)? (long answer)

normal:

- uniform, striated muscle fibres

- centrally located nuclei

- very few inflammatory cells (purple dots)

- eosinophilic cytoplasm

- neat arrangement

---

inflammation:

- muscle fibres beginning to lose structure

- numerous inflammatory cells (purple dots)

- some loss of nuclei or hypereosinophilia (hallmarks of necrosis)

---

coagulative necrosis:

- muscle fibres still have overall architecture

- numerous inflammatory cells (slightly less than "inflammation" + more localised)

- nuclear dissolution (either complete loss or karyolysis)

- hypereosinophilia

- less distinct striations

what are the key differences between the difference tissue stages of a myocardial infarction/coagulative necrosis?

ischemic coagulative necrosis >>> strongly eosinophilic and anuclear myocardial fibres

---

widespread leukocyte invasion = early phase

more localised leukocyte invasion = later phase

---

would still see myocardial fibre architecture but slightly deviated from normal tissue (some gaps)

[visual] myocardial coagulative necrosis

-

what macroscopic observations would be made in the instance of myocardial infarction (coagulative necrosis)?

depends on how long the patient survives post-infarction

---

normal appearance initially

---

then swollen and reddish (leukocyte infiltration)

---

then swollen and pale (coagulative necrosis)

---

then firm and white (fibrosis/scar tissue)

how can macroscopic observation aid in the determination of when an infarction has occurred? (i.e., recent onset vs. historic onset/past event)

recent = swollen and red (since there is leukocyte infiltration/inflammation)

historic/past = white (since fibrosis has occurred/scar tissue formed)

looking at a heart, you see areas that are white, areas that are yellow, and areas that are red; what is each a result of?

yellow = myocardial steatosis (fat deposition) due to ischemia or altered metabolism

white = scar tissue from previous necrotic event (e.g., myocardial infarction)

red = leukocyte infiltration/inflammation; likely result of recent myocardial infarction (i.e., pre-necrotic)

in terms of coagulative necrosis, what are the two ultimate outcomes of a myocardial infarction?

1. healing

necrotic tissue is replaced by scar tissue (fibrosis) (indicates past MI)

would appear white macroscopically

---

2. extensive necrosis

ischemia was severe/prolonged, delaying the healing of necrotic tissue (indicates recent or more severe MI)

would appear black macroscopically

why does extensive necrosis following myocardial infarction appear as black tissue macroscopically?

haemolysis products (e.g., haemosiderin) with black pigment + dead cell debris

what further complications can arise as a result of coagulative necrosis? (answer in context of heart)

rupture of necrotic tissue

---

occurs because the necrotis tissue is soft

in the context of MI/coagulative necrosis; what is the location, effect, and consequence of a free wall rupture?

myocardium

---

blood pools into pericardial sac

---

cardiac tamponade (=pressure on heart from too much blood/fluid in pericardial sac)

in the context of MI/coagulative necrosis; what is the location, effect, and consequence of a septal rupture?

full thickness tear of septum (i.e., endocardium and myocardium)

---

left to right shunt (i.e., blood flows from left side of heart to right side of heart instead of to the body)

---

acute heart failure

in the context of MI/coagulative necrosis; what is the location, effect, and consequence of a papillary muscle rupture?

papillary muscle (ventricular valves)

---

valve regurgitation (i.e., valves do not function properly and allow backflow of blood)

---

acute heart failure

when would coagulative necrosis occur in the lung?

in ischemia (e.g., pulmonary thromboembolism) ALTHOUGH liquefactive/caseous necrosis is more common

what onset/symptoms are associated with pulmonary thromboembolisms?

sudden onset

---

breathlessness (since cannot oxygenate blood efficiently but body trying to compensate)

---

can be fatal

in terms of severity, why and how does necrosis differ between the heart and lung? (with particular focus on coagulative necrosis)

longs have a dual blood supply so total ischaemia is less common (hence less severe consequence)

summarise the key aspects of coagulative necrosis?

occurs in firm tissue (primarily heart, kidney, spleen) (also in lung even though it is soft tissue)

---

characteristic nuclear dissolution (pyknosis > karyorrhexis > karyolysis) and eosinophilia

---

associated with ischemia/infarction

---

most common in MI

---

red = very recent (inflammation/leukocyte invasion)

white = historic (scar tissue)

black = severe necrosis not yet healed

yellow = not necrosis but steatosis (also related to ischemia)

---

necrotic tissue can rupture leading to further complications (e.g., cardiac tamponade or acute failure)

what is liquefactive necrosis?

necrosis that results in the tissue becoming very soft/liquified (broken down into a liquid)

---

results in dead tissue being "replaced" by fluid filled cyst

---

(i.e., tissue undergoes liquefactive necrosis >>> becomes liquid or semi-liquid >>> solid cells dissapear (they are now fluids) which creates a crater that said fluid will fill)

what tissue type/injury is associated with liquefactive necrosis?

tissues with a lot of fluid (primarily the brain (fairly unique to brain)) (can also be the lung)

---

can be result of ischemic injury or infection (leading to anoxia/hypoxia) (as with all types of necrosis)

in the context of liquefactive necrosis, how does a cyst differ from an abscess?

cyst = does not tend to contain pus/is result of ischemic injury

abscess = contains pus/is result of infection

why is brain liquefactive necrosis so serious?

the brain has almost no capacity to repair

---

any damage will be lifelong

how does coagulative necrosis and liquefactive necrosis differ? (main point)

coagulative = maintains some tissue structure

liquefactive = results in structure being broken down by enzymes, creating gaps

what is gangrenous necrosis?

a further complication of necrosis that occurs when the necrotic tissue becomes invaded by organisms that further breakdown the tissue

---

applies to almost all external necrosis (i.e., on skin, etc.) since it is especially prone to infection

why is gangrenous necrotic tissue often green or black?

haemoglobin is often broken down (releasing pigments)

---

formation of iron sulfide products (e.g., ferrous sulfide/FeS) = black/dark green colour

---

the haemoglobin produces iron and the infectious agent (if clostridium) will produce hydrogen sulfide (H2S) >>> FeS +H2 (gas) (===gas gangrene)

when/where is gangrenous necrosis common?

in an ischemic bowel

---

in a strangulated hernia (i.e., hernia with compromised blood flow)

---

in the toes of a diabetic

why are toes a common site of gangrenous necrosis in a diabetic?

toes are the most distal part of the body (i.e., the farthest from central circulation)

---

they have the smallest vessels (i.e., are easily blocked)

what are the three different forms of gangrene? (for each: associated with? onset? pain? gas? site?)

gas

= associated with clostridium infection

= very rapid onset

= severe pain

= gas present

= common in muscles

---

wet

= associated with infection (e.g., streptococcus pyogenes)

= rapid onset

= severe pain at first but numbs later

= rarely gas present

= common in bowel and diabetic foot

---

dry

= associated with severe ischemia and NO INFECTION

= slow onset

= often painless (due to nerve death)

= no gas present

= common in toes/fingers

---

dry = always occurs externally on body (must have air exposure)

describe briefly how an ischemic bowel may result in gangrenous necrosis?

bowel is naturally full of bacteria

>>>

ischemia

>>>

necrosis occurs

>>>

bacteria released (hence may contribute to further tissue breakdown (=gangrenous necrosis))

---

likely wet gangrene

describe briefly how a strangulated hernia may result in gangrenous necrosis?

ischemia

>>>

necrosis occurs

>>>

secondary infection by bacteria (usually from our microbiome/gut)

>>>

wet gangrene

describe briefly how a diabetic's toes may become gangrenous?

high blood glucose can damage small vessels overtime and so slight damage to extremities are difficult to recover from

---

slight damage

>>>

tissue becomes necrotic

>>>

secondary infection occurs (since necrotic tissue is ideal breeding site)

>>>

can be wet/dry/gas gangrene - depends on infection status/type

what is gas gangrene?

a lethal infection of soft tissue by clostridium species (especially C. perfringens)

what are the key differentiating factors between dry gangrene and coagulative necrosis? (2)

dry = needs ischemia and air exposure + happens externally

coagulative = needs ischemia only + happens internally

what is caseous necrosis?

a combination of coagulative and liquefactive necrosis that results in a cheesy appearance of dead tissue

---

most commonly caused by tuberculosis (also seen in fungal infection)

in a clinical setting, how could necrosis be identified? (combination of 3 things)

often can consider signs/symptoms with imaging to determine if necrosis (general) has occurred/is occurring

---

can use radiological scanning to visualise potential necroses (necrotic tissue often appears differently in scans )

---

biopsy required to confirm type of necrosis

how would coagulative necrosis appear in a radiological scan?

(CT) low-density areas (darker compared to surrounding tissue)

---

(MRI) hypointense areas (darker) with preserved outline

how would liquefactive necrosis appear in a radiological scan?

(CT) fluid-filled or cystic areas with well defined margins (relatively dark)

---

(MRI) hyperintense areas (brighter)

how would gangrenous necrosis appear in a radiological scan?

easiest to establish gas of the three

---

(CT) gas bubbles

---

(X-ray) can see gas in tissue

how would caseous necrosis appear in a radiological scan?

(CT) low-density areas surrounded by denser granulomatous tissue (darker and darkerer)

---

(X-ray) possibly can see granulomas or cavities (if in lung) (lung is most common site)

how would fat necrosis appear in a radiological scan?

would see areas with dense fat (darker areas)

how would caseous necrosis be identified clinically?

radiological scan would pick up a mass in the lung

---

biopsy may be required to determine/confirm necrosis

why does caseous necrosis result in a "cheese-like" substance? (what is it/why does it happen) (compare to coagulative and liquefactive)

substance = clumped cell debris that creates a soft granular mass

---

coagulative = cell membranes/skeletons remain largely intact (no significant lipid release) - tissue stays firm

---

caseous = cell membranes completely break down >>> release of lipids, proteins, and other cell material >>> soft/cheesy/crumbly texture

---

doesn't become liquidified like in liquefactive because enzymes that would do this are not as active in this region of the body (the immune response differs depending on area of body)

how does caseous necrosis histologically manifest?

as granulomas (kind of looks like a well defined oval/circle with a paler rim) (pale rim = leukocytes fighting inflammation)

aside from manifestation as granulomas, what other microscopic identification exists for caseous necrosis?

large/multinucleated cells + staining for tuberculosis identification

what stain would be used to identify tuberculosis in suspected infection? (aiding caseous necrosis identification)

Ziehl-Neelson (acid fast stain) (mycobacterium are acid fast since lots of mycolic acid in wall (relatively unique feature))

what is fat necrosis?

not technically a specific/unique form of necrosis

---

descriptive term used when there is necrosis in adipose tissue (i.e., fat destruction)

---

can be coagulative (firm tissue/lung), caseous (lung/lymphatic), or liquefactive (brain/lung) (location-dependent)

why is fat necrosis a clinically important diagnosis? (use pancreas/breast as examples)

it is often an early indicator of a more serious underlying condition

---

can help diagnose/confirm pancreatitis (degree of fat necrosis can aid determination of severity)

---

can occur in breast tissue and be mistaken for cancer in imaging - identification of fat necrosis here helps avoid unecessary treatments/procedures

what would lead to pancreas-associated fat necrosis?

chronic alcohol consumption

>>>

pancreatic inflammation/damage (=acute pancreatitis)

>>>

release of prematurely-activated pancreatic enzymes (i.e., should normally only become active once they reach the intestine) to surrounding adipose tissue

>>>

uneccessary digestion of adipose tissue (necrosis initiation)

how would fat necrosis appear histologically?

normal fatty tissue = lots of gaps/white space (=fat)

---

necrotic fat tissue = still has gaps/white space, but less neat distribution + more cells present (inflammatory cell invasion)

in summary, what happens following necrosis? (3 main)

1. dead cells/debris eventually removed by phagocytes

---

2. inflammatory response (inflammatory cell infiltration with organisation and repair)

---

3. sometimes dead tissue remains leading to dystrophic calcification

what is dystrophic calcification?

deposition of calcium salts in damaged or necrotic tissues, occurring despite normal calcium and phosphorus levels in the blood

---

necrotic tissue composed of cellular content (normally intracellular)

>>>

cellular content provides ideal environment for deposition of calcium ions (primarily combination of phospholipids + calcium ions > calcium phosphate = deposition form)

in summary, what cell size is associated with apoptosis and necrosis?

apoptosis = reduced (shrinkage)

---

necrosis = enlarged (swelling)

in summary, what nuclear morphology is associated with apoptosis and necrosis?

apoptosis = fragmentation into nucleosome-size fragments (~apoptotic bodies)

---

necrosis = pyknosis > karyorrhexis > karyolysis

in summary, what membrane status is associated with apoptosis and necrosis?

apoptosis = intact but with altered structure (particularly for lipids)

---

necrosis = disrupted (differs with each type)

in summary, what cellular content fate is associated with apoptosis and necrosis?

apoptosis = intact/released in apoptotic bodies

---

necrosis = enzymatic digestion; may leak out of cell

in summary, what association exists between apoptosis/necrosis and adjacent inflammation?

apoptosis = no association

---

necrosis = frequent damage to adjacent tissue/cells

in summary, what association exists between apoptosis/necrosis and physiological or pathological status?

apoptosis = often physiologic (may be pathologic after some forms of cell injury (e.g., DNA damage))

---

necrosis = invariably pathologic (usually a culmination of irreversible cell injury)

what difference exists between necrotic and normal tissue in the context of sampling/preparation by a BMS?

necrotic tissue is associated with technical challenges