THAD FINAL IMAGes

1/57

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

58 Terms

A !Kung Camp The Primitive Hut, 1755

From Marc-Antoine Laugier’s Essai sur l’architecture

The !Kung hut represents indigenous architectural practices rooted in harmony with the natural environment. Conversely, The Primitive Hut symbolizes a Eurocentric view that perpetuates a false dichotomy between reason and the natural world. This comparison challenges conventional notions of progress and modernity.

Ochre found in Blombos Cave

The advanced understanding and utilization of resources in indigenous communities reveal a sophisticated grasp of mobility, geology, technique, and geography, challenging the primitive stereotype perpetrated by Europeans. Moreover, the view of technique as an extension of the body emphasizes the overlap of nature, body, and mind, offering a holistic perspective on resource utilization that transcends the notion of natural resources as mere tools to be exploited.

The Himba women in Nambia in southwest Africa still grind ochre by hand

Ochre, used in rituals to regulate hunting practices and enhance visibility to ancestors, is a symbol of connection to tradition and ancestral knowledge; this also underscores the role of women in preserving cultural practices. Furthermore, the use of ochre reflects a conservationist ideology, illustrating how indigenous communities integrate environmental sustainability into their rituals and everyday life.

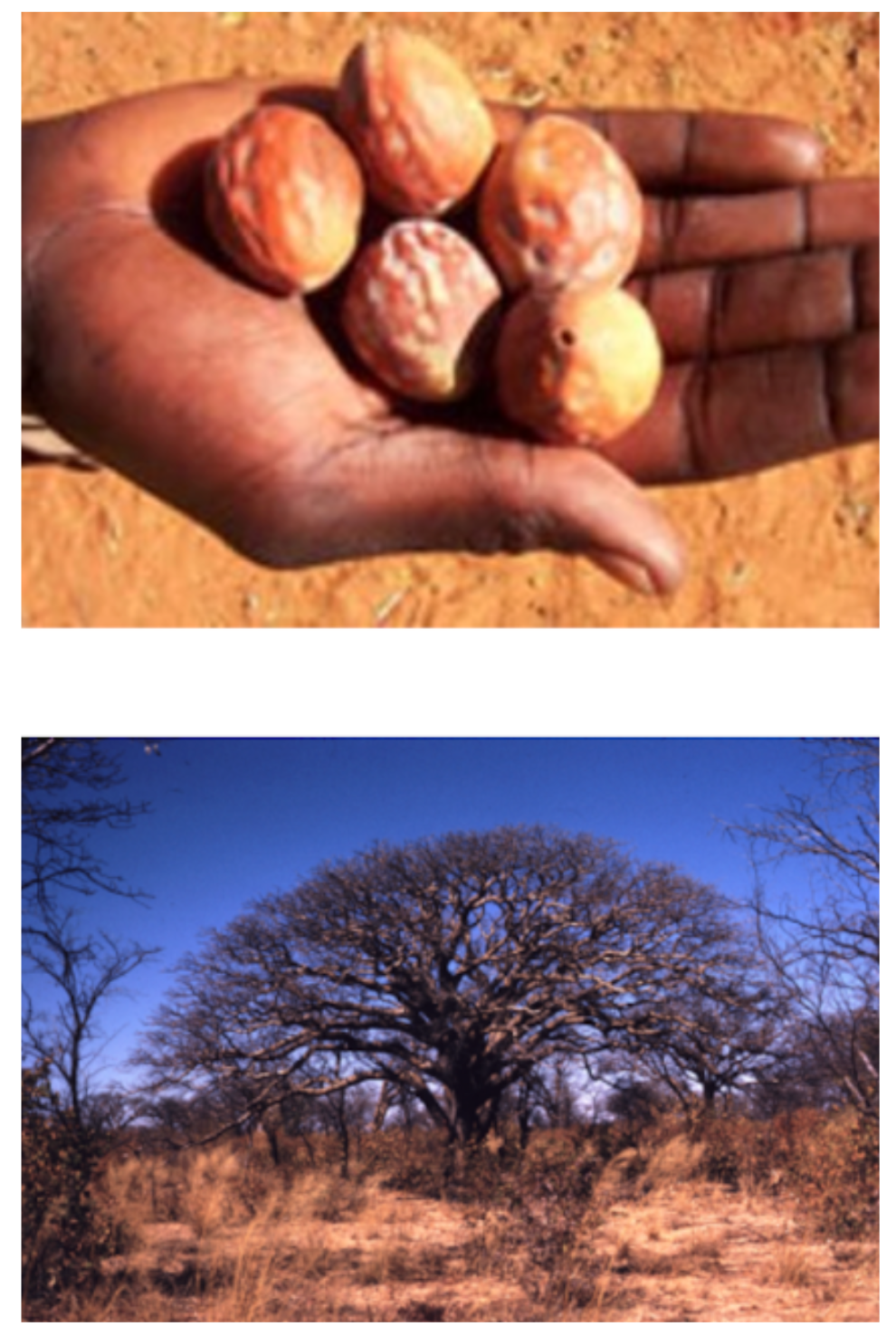

Mile long Mongongo groves (dark lines) in Botswana growing on the sandy soil of ancient dunes

The groves symbolize a communal and equitable system of resource allocation, where trees are distributed between tribes along lines instead of sections. Unlike the European emphasis on individualist land ownership, this reflects a deliberate effort to prevent hierarchy and promote equality among community members. Additionally, the cross-pollination of the trees underscores the interconnectedness and interdependence of nature and people.

!Kung Botswana

approach to architecture and resource management within indigenous communities. It challenges the stereotype of indigenous architecture as primitive or stuck in the past by showcasing the sophisticated systems and knowledge embedded within their practices. The involvement of women in controlling these systems highlights the importance of gender dynamics and communal decision-making processes in indigenous societies. Illustrates how indigenous architecture acknowledges the sacredness of nature, rejecting the notion of nature as a passive resource to be exploited.

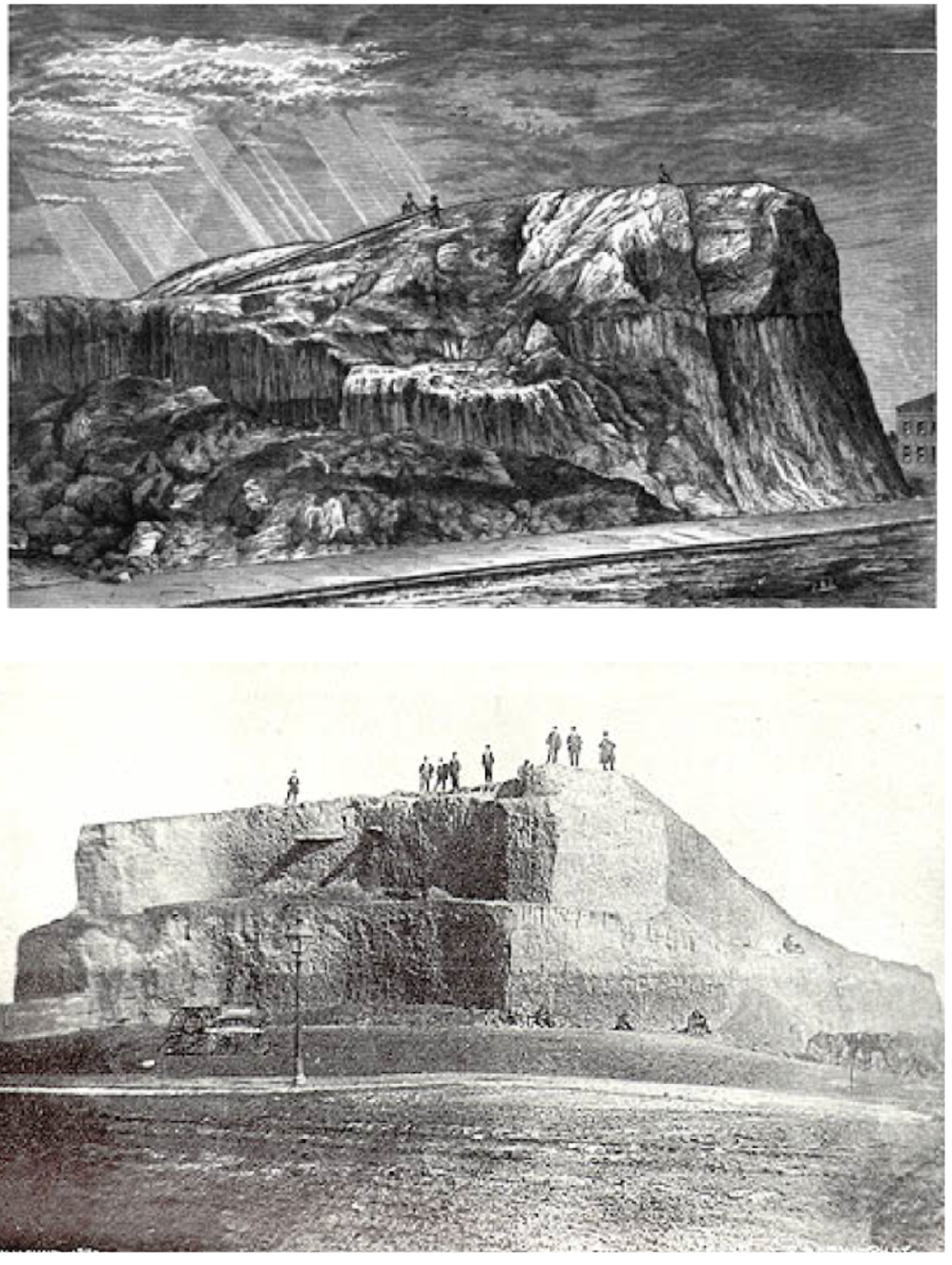

Poverty Point 1800 BC Louisiana

The site's layout features mounds that align with different solar and seasonal points, reflecting a deep understanding of astronomy and a connection to the natural world. Constructed using different colored pieces of land sourced from various locations underscores the collaborative effort and extensive network of indigenous communities involved in its creation.

Big Mound of St. Louis, destroyed Spring 1869 so that Native Americans would not use it as a sacred site, From Switzler’s Illustrated History of Missouri (1541 - 1877)

Serves as a poignant symbol of the violent erasure of indigenous sacred sites and cultural practices by colonial powers. This monumental mound, one of the largest ritualistic sites, embodied a collective sense of identity and connection to the past and the universe. Its destruction following the Louisiana Purchase reflects a disturbing history of cultural obliteration and colonial violence, highlighting the need to acknowledge and preserve indigenous heritage rather than perpetuate acts of othering and destruction.

Spider Grandmother 200 BC - 500 CE, Hopewell

Symbolizes the profound interconnectedness between indigenous cultures, their mythology, and the landscape. This monumental structure, representing the mythical figure of Grandmother Spider, served as a cultural landscape embodying continuity between the land, the underworld, water, and the sky. Its construction reflected a deep cosmological understanding, with different sides aligning with cosmological movements throughout the year. However, the sacredness of such sites has been eroded over time by modern developments like housing developments and golf courses, highlighting the loss of connection to nature and the spiritual heritage of indigenous peoples.

Bedroom for Lina Loos, Adolf Loos, 1903

a manifestation of gendered architectural discourse. Loos's design reflects the popular belief in the dichotomy between form and matter. The white walls in the bedroom are meant to symbolize control over sensuality, portraying sensuality as a subordinate element to the dominant form. This notion of controlled form as a means to exclude and oppress the feminine underscores the gender biases prevalent in architectural practice and discourse.

Josephine Baker House Project

Holds significance as a manifestation of gendered and racialized architectural discourse. Loos's design for the famous black dancer and actress Josephine Baker reflects the exoticization and sexualization of Baker as an African figure by the media. The house project emphasizes sensuality, portraying Baker as the uncontrolled sensual matter, while Loos's design attempts to control and showcase her feminine sensuality through architectural elements. This example highlights how architecture can perpetuate gender and racial stereotypes, reinforcing power dynamics and inequalities in the built environment.

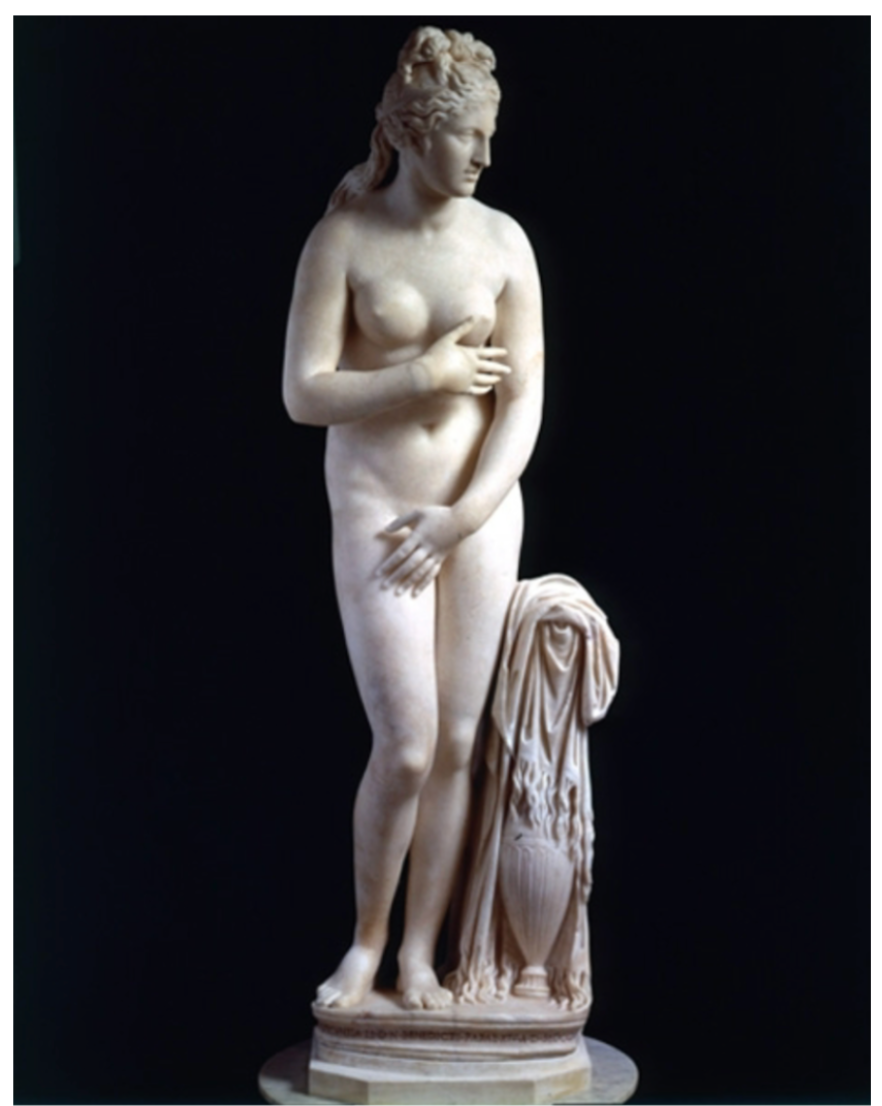

Capitoline Venus 200 CE & Riace “Warrior A”450 BC

The comparison of the Capitoline Venus and Riace "Warrior A" statues underscores how classical sculptures reinforce gendered norms and perceptions of sensuality, depicting masculinity as controlled and femininity as uncontrolled. Riace "Warrior A" portrays an idealized masculine form, characterized by controlled body hair and his confident manner, delineating separation from sensual matter. In contrast, the Capitoline Venus embodies uncontrolled sensuality, as indicated by the folds of her cloth (representing her genitals) and her apparent shame.

Villa Savoye, Le Corbusier, 1928-1929

The building, hailed as a "machine to live in," embodies principles of rationality and functionality, aiming to transform the way inhabitants live. However, Le Corbusier's focus on the aesthetic presentation of the building as a "machine" highlights a disconnect from the human hands and labor that bring it into existence, suggesting a prioritization of form over matter. This analysis underscores broader themes of control, representation, and exclusion within architectural discourse, particularly concerning gendered and racialized perspectives on design and construction.

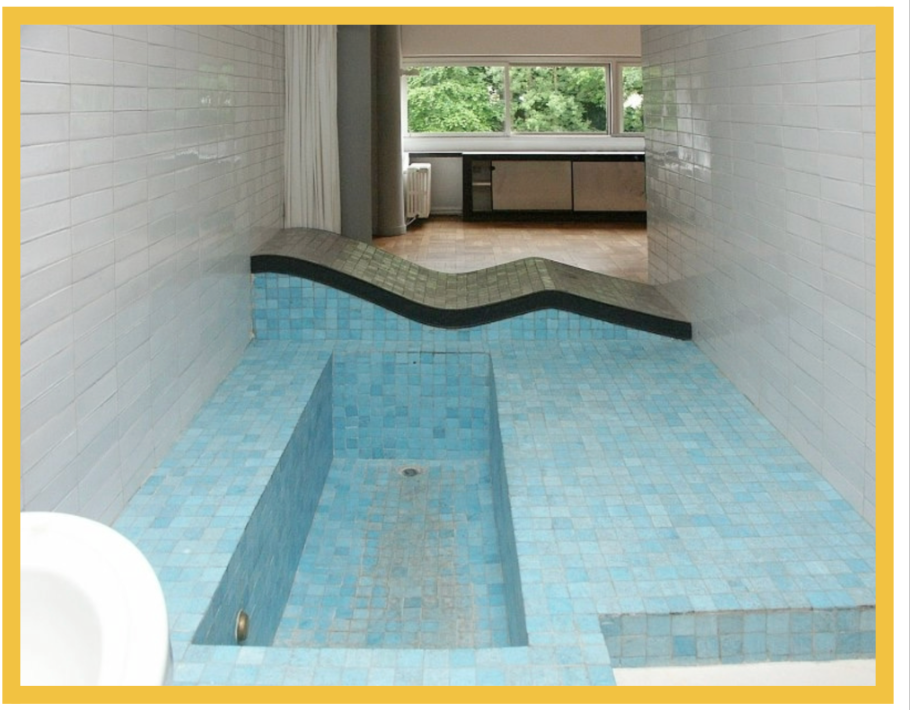

Bathroom in Villa Savoye, Le Corbusier, 1928-1929

The design of the bathroom, with its distinct lines separating the bath area from the rest of the room, symbolizes a threshold that delineates between sensuality and reason, masculine and feminine realms. This spatial configuration reflects the architect's desire to impose order and control, framing the transition between matter and form in a way that reinforces traditional gender norms. Le Corbusier's statement on decoration as suited to "simple races, peasants, and savages" further underscores the hierarchical and exclusionary attitudes prevalent in modernist architecture.

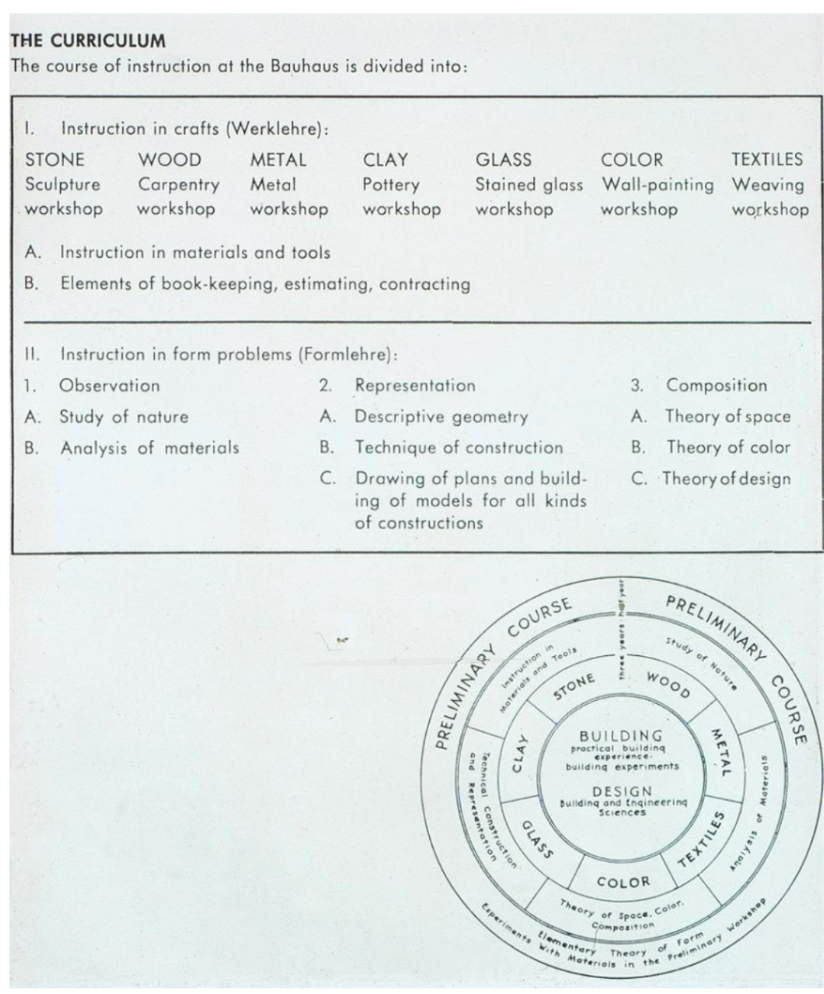

Bauhaus School Course Curriculum 1919-1933

importance in understanding the pedagogical approach of the Bauhaus movement. It emphasizes the foundation course's focus on universal design principles, abstraction, and modernism. However, the lecture also highlights the gendered and hierarchical nature of the curriculum, where material-based majors are associated with femininity and placed at the bottom of the hierarchy, while architecture and design, considered masculine, are reserved for advanced students, predominantly white men. This illustrates the complexities of neutrality and power dynamics within the Bauhaus pedagogical framework, which continues to shape contemporary design thinking and practice.

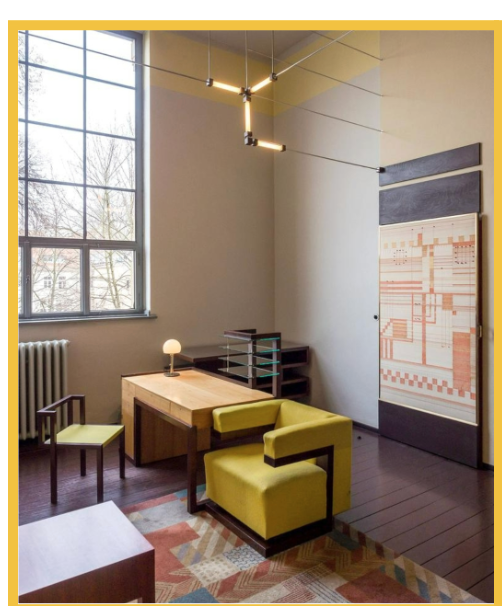

Director’s Office, Walter Gropius 1923-24

Holds significance as a quintessential example of Bauhaus-era modern design principles. It epitomizes the pursuit of purity, simplicity, and form through geometric abstractions and primary shapes, aimed at activating the space around it. The office's layout and isometric view symbolize the ideal of neutral, objective space, reflecting the Bauhaus's emphasis on organization and proper placement, while also highlighting the inherent tension between the aspiration for neutrality and the power dynamics embedded within the design.

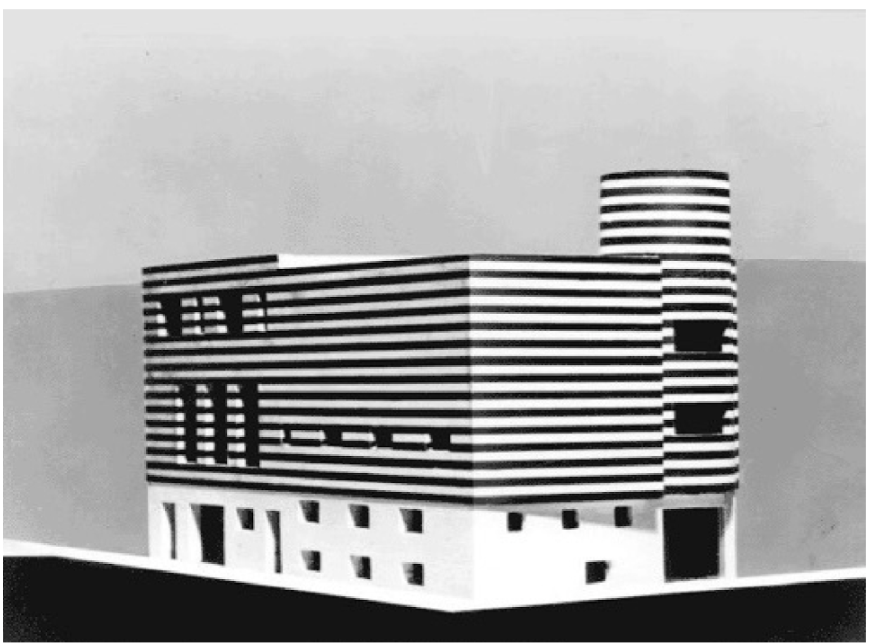

Bauhaus Building, Dessau, 1925-1932, (built 1925)

The building’s emphasis on geometric abstractions and primary shapes reflects the movement's pursuit of purity, simplicity, and form, aiming to activate the space around it. Through its innovative use of glass-enclosed studios and movable windows, the building creates a dialogue between positive and negative space, evoking a sense of transparency and openness while serving as a stage for architectural experimentation and expression.

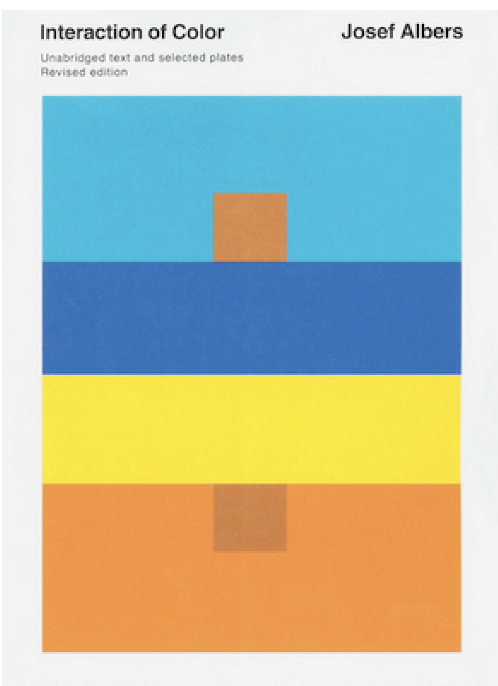

Interaction of Color Josef Albers, 1963

Holds significance as a seminal work challenging perceptions of color and visual experience. Albers aims to push viewers to see beyond the impurities of the world and into a realm of purity through exercises that reveal the subjective nature of color perception. By highlighting the discrepancy between objective reality and subjective interpretation, Albers prompts a deeper understanding of the human visual system and the complexities of perception.

Hardware Jewelry, Anni Albers and Alex Reedc. 1940-46

Holds significance as an exploration of the blurring boundaries between textile, weaving, and industrial design. By incorporating found objects and embracing the lack of purity in materials, Albers challenges notions of fixed cultural identities and hierarchies. The piece prompts reflection on the interconnectedness of cultures and the need to recognize movement and overlap within ourselves and others, fostering a deeper understanding of diversity and complexity.

Bretton Woods Monetary Conference July 1-22, 1944

Marked a pivotal moment in global economic history, where Western countries, including the UK, attempted to establish new economic regulations for world trade. However, it reflects the legacy of colonial exploitation, as Western nations sought to address the economic fallout from centuries of extraction of wealth from countries like India, totaling over $45 trillion. Despite the establishment of institutions like the World Bank, IMF, and GATT, the conference underscores the unresolved issue of unpaid debt owed to formerly colonized nations, highlighting the ongoing impact of colonialism on global economic systems.

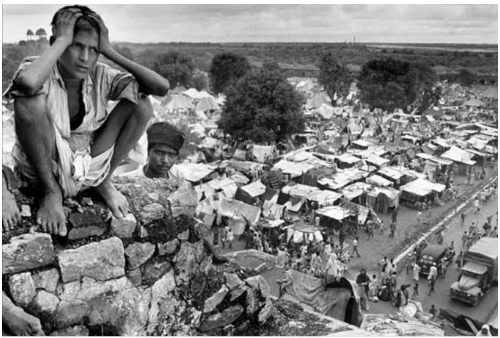

Partition of India and Pakistan, Margaret Bourke-White 1947

Serves as a stark reminder of the human cost of colonialism and the legacy of unpaid labor. It symbolizes the creation of the concept of "third world" countries by Western powers, highlighting the unrepresented faces of those who endured exploitation and hardship. Underscores the harsh conditions faced by individuals affected by colonial policies, raising questions about the unresolved issues of economic inequality and the lasting impact of colonial exploitation on global economic systems.

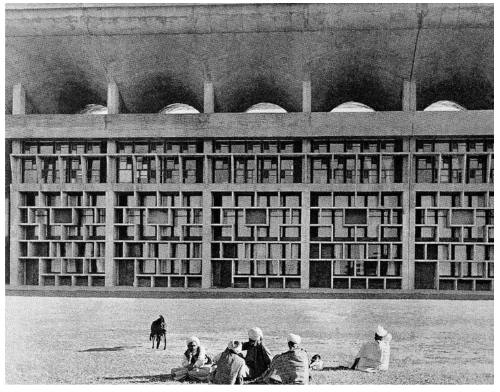

“The High Court” from Oeuvre Complete, Le Corbusier

Represents the architectural embodiment of modernism and its integration with nature, echoing the silhouette of the Himalayas. However, it also evokes criticism for its perceived ugliness and the disconnect between the architectural vision and the lived experiences of the people it serves. The building's brutalist design reflects a desire to start anew, yet overlooks the unresolved issues of unpaid debt and the lasting effects of colonialism on the nation-state of India.

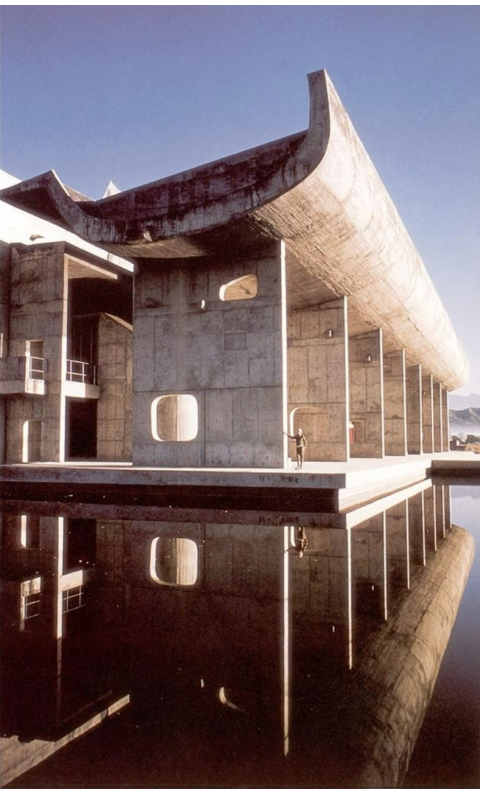

Assembly Building, Chandigarh, India, Le Corbusier, 1955

Reflects the influence of modernism and the desire to make a bold impression on the global stage. Despite the presence of qualified local Indian architects, the decision to commission Le Corbusier underscores the prioritization of a modern aesthetic over indigenous talent. This building served as a major milestone in Le Corbusier's career, propelling him to fame, yet it also raises questions about the true beneficiaries of such grand architectural endeavors and their alignment with global capitalist interests.

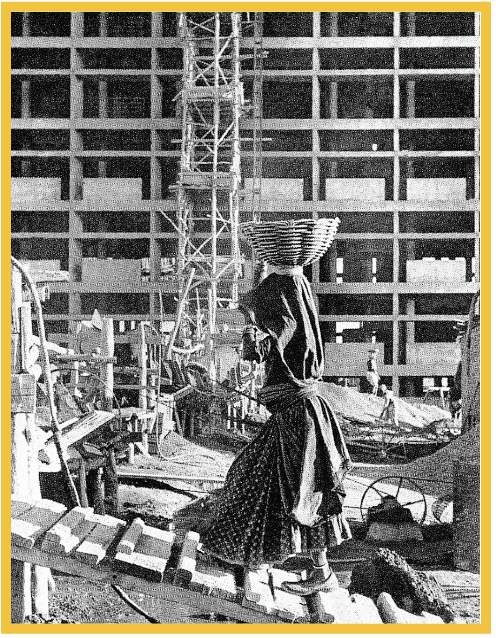

“Chandigarh, Capital Complex, construction photograph” from Oeuvre Complete, Le Corbusier

Symbolizes India's ascent towards progress, juxtaposed with the obscured faces of the exploited laborers who contributed to its construction. It highlights the political dimensions of architecture, prompting reflection on the lives of those whose labor remains invisible behind monumental structures and emphasizing the pervasive influence of capitalism, colonialism, and slavery in shaping built environments.

METI “Hand-made” School, Rudrapur, Bangladesh, Anna Heringer, Architect, From MoMA exhibition catalog, Small Change Big Change, 2011

Exemplifies an approach to architecture focused on community involvement and utilization of local materials. However, it also highlights the complexities of social interventions in design, as seen through the unintended consequences of the architect's lack of understanding of the area's history, including displacement issues caused by colonial laws and bamboo shortages. Prompts critical examination of the balance between problem-solving in design and the need to recognize and address historical complexity and social inequalities.

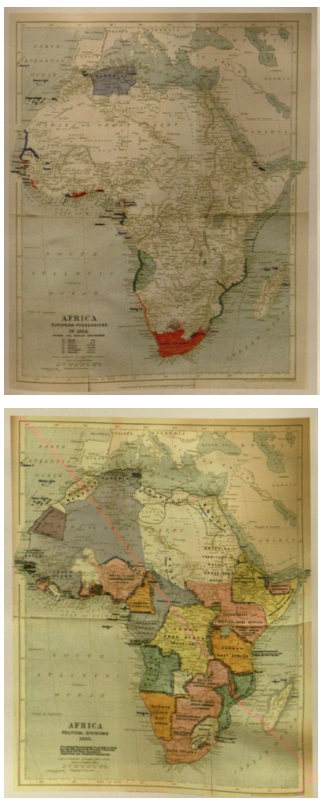

Map of the Scramble for Africa (depicts Africa before the Berlin Conference and after)

Exemplifies how colonial powers imposed their control over African territories without regard for existing social structures or indigenous autonomy. This historical event not only divided communities and disrupted traditional ways of life but also laid the foundation for enduring social, economic, and political challenges across the continent. This underscores the importance of acknowledging historical injustices and considering indigenous perspectives when addressing societal problems through design.

“Lagos” in Mutations, Rem Koolhaas, 2000

Koolhaas's approach, which focuses on studying megacities like Lagos, reflects a critique of capitalism's influence on architecture and emphasizes the need for adaptation to global transformations. However, the lecture suggests a criticism of Koolhaas's approach, as it may overlook the nuanced spatial dynamics and historical complexities of subaltern communities. While Koolhaas advocates for creativity and flexibility in architectural solutions, the lecturer challenges the notion of universal creativity, arguing that it is a privilege not accessible to all, particularly those oppressed by colonialism and poverty. Thus, "Lagos" in Mutations exemplifies the tension between problem-solving in design and the need to recognize and address historical, social, and economic complexities in architectural interventions.

LifeStraw: Personal filter as a “solution” to “Third World Development”

Serves as an example of well-intentioned yet flawed solutions imposed on African communities. Originally developed for Western markets, its adaptation for African use highlights the disconnect between the perceived needs of these communities and the practical realities they face. The struggles encountered, such as the device's physical requirements, underscore the complexity of addressing systemic issues through simplistic solutions. Ultimately, LifeStraw symbolizes the pitfalls of imposing solutions without a deep understanding of the social, cultural, and environmental contexts in which they are implemented.

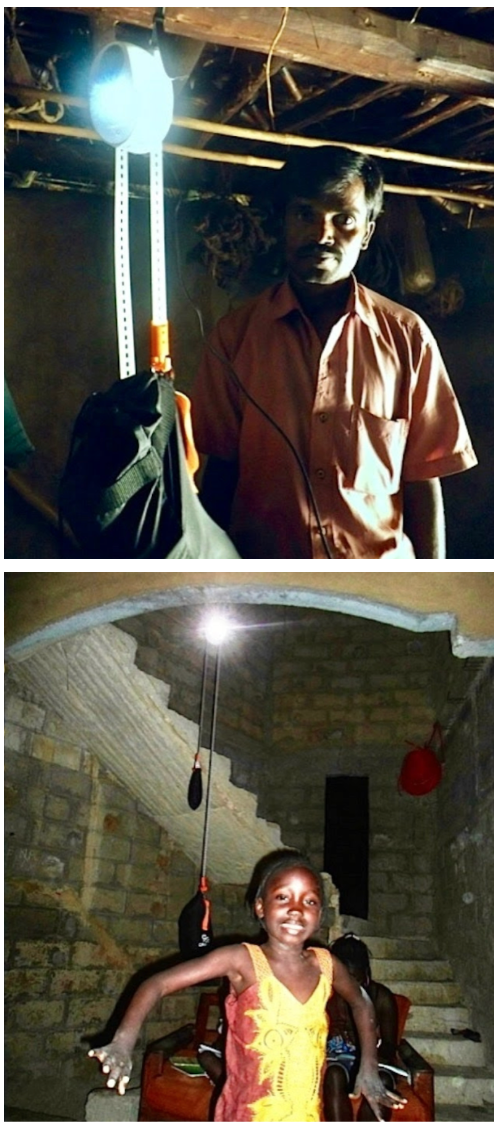

GravityLight

In the lecture's discourse on problem-solving in design, the GravityLight emerges as another example of a well-intentioned yet misguided solution imposed on communities in need. Marketed as an alternative to kerosene or candle lighting, it overlooks the nuanced preferences and desires of the users, such as a human desire for ambient lighting. This parallels the critique of LifeStraw, highlighting the tendency to provide simplistic solutions that appease donors' consciences while neglecting to address the underlying complexities of systemic issues.

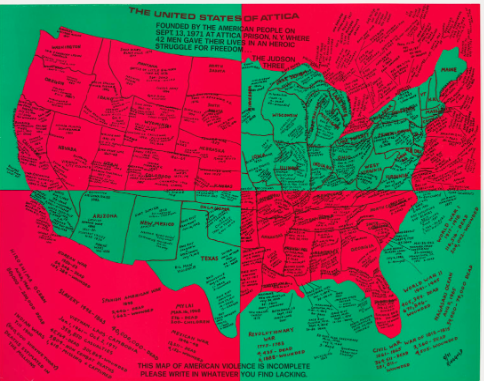

United States of Attica, Faith Ringgold, 1971

serves as a powerful visual representation of systemic violence and oppression in the United States. By inviting viewers to add to the map, Ringgold prompts critical reflection on the ongoing nature of U.S. brutality and encourages engagement with archives of racist, imperialist, and police violence, highlighting whose histories are prioritized and preserved within archival contexts.

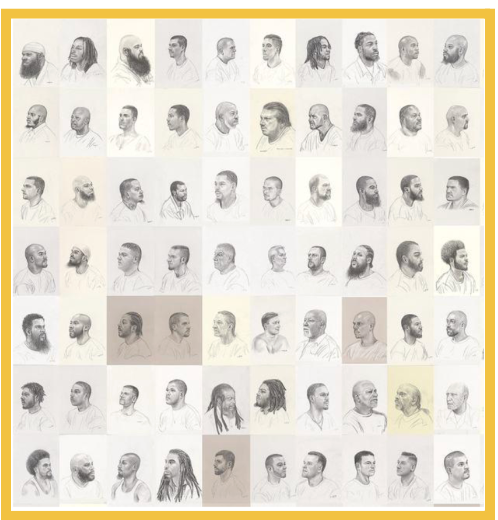

Pyrrhic Defeat: A Visual Study of Mass Incarceration, Mark Lo, 2014-Present

Loughney's ongoing project, consisting of graphite drawings of individuals who were incarcerated alongside him, serves as a unique form of archive. By creating this visual study in collaboration with those who shared his condition, Loughney challenges conventional archival practices and offers a deeply personal perspective on mass incarceration, highlighting the importance of lived experiences within the archival context.

System for a Stain, Candice Lin, 2016

Lin's piece visualizes the historical connections between commercial trade, violence, and imperialism, particularly through the stain on the floor symbolizing bloodshed and exploitation. By reexamining colonial objects like cochineal and incorporating archival research into her work, Lin prompts viewers to reconsider their relationships with objects and confront the legacies of slavery and colonialism embedded within them.

Keep for Old Memiors,Betye Saar, 1976

Saar's piece, part of a series of assemblages honoring her great-aunt Hattie Parson Keys, reflects a sentimental journey into the past through fragments such as letters, fabric scraps, and gloves. Through collage and repurposing of ancestral artifacts, Saar engages in a dialogue between archive and African American artistic practice, inviting viewers to contemplate the significance of memory, preservation, and ancestral history.

An Archive of Our Own Akea Brionne 2019

Brionne's work serves as both a critique and exploration of the photographic medium, using the historic tintype process to highlight the medium's limitations in capturing darker skin tones. Through this exploration, Brionne frames the relationships between black mothers and daughters, inviting viewers to consider the complexities of black maternal relationships within the context of historical representation and archival practices.

Independence Hall, Philadelphia, A UNESCO World Heritage Site , A US National Park site (since 1956)

Angkor Wat, Cambodia A UNESCO World Heritage Site

Angkor Wat similarly exemplifies the intersection of preservation, tourism, and cultural heritage. The sophisticated campaigns to secure its UNESCO status underscore preservation's role in economic development through increased tourism revenue. However, these efforts also highlight the need to balance economic interests with the preservation of cultural heritage and community involvement. Both sites serve as poignant examples of the complex dynamics surrounding preservation efforts worldwide, where considerations of power, privilege, economic interests, and cultural heritage intersect.

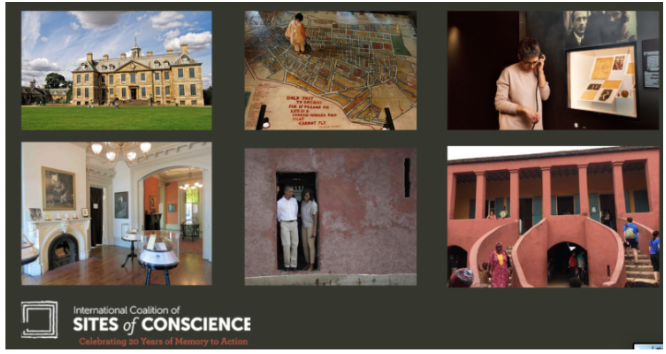

International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, Founded 1999

“Celebrating 30 Years of Memory to Action”

Marks a significant development in the preservation field by providing a global network dedicated to promoting and protecting human rights through historic sites, museums, and memorials. By focusing on sites of difficult histories and facilitating tough conversations about the present, the coalition challenges traditional preservation approaches that may overlook or silence marginalized narratives. Its emphasis on confronting themes such as immigration, genocide, and slavery underscores the importance of acknowledging and reckoning with the past to create more inclusive and equitable preservation practices.

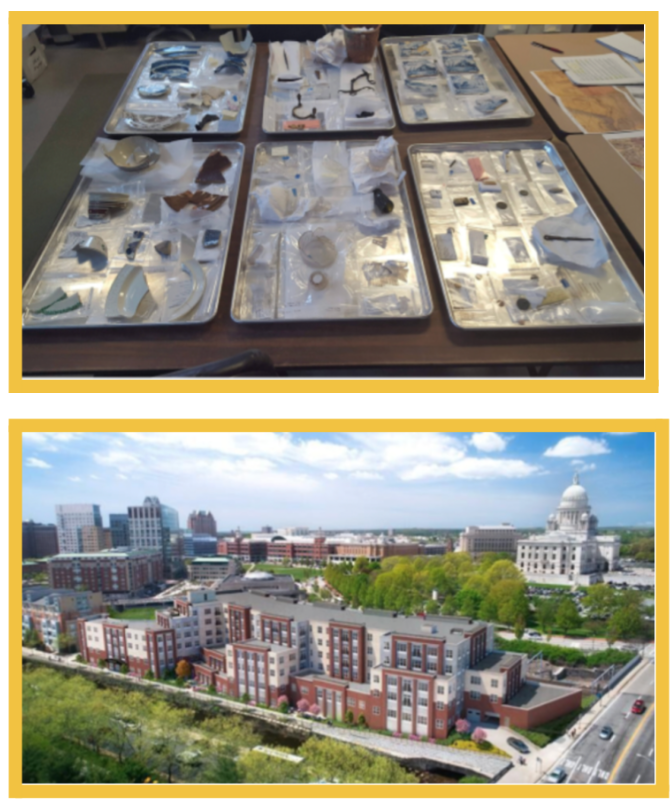

A Selection of Artifacts from Snowtown

aiming to expand public understanding of the complex history of Snowtown, a racially and ethnically diverse working-class neighborhood that stood for almost a century. The Snowtown Project seeks to challenge perceptions of Snowtown as merely a slum by uncovering stories of courage, creativity, and resilience among its inhabitants. As the neighborhood no longer exists due to demolition for railroad tracks, preservation efforts have shifted towards creatively using artifacts to reimagine and preserve the rich history of Snowtown, emphasizing the importance of considering and preserving the stories of places that were not traditionally recognized in preservation efforts.

Critical Race Design Studies

Design Justice Sasha Costanza-Chock

Critical Race Design Studies and Design Justice are both significant concepts in the context of the lecture's exploration of how preservation and design intersect with issues of race and social justice. Critical Race Design Studies offers an interdisciplinary approach to analyzing and critiquing the systemic mediations of racial identity within visual communication and graphic objects, echoing the lecture's examination of how preservation practices may perpetuate racial biases. Meanwhile, Design Justice emphasizes community-led practices in design to address systemic inequalities and create more inclusive environments, echoing the lecture's call for preservation to be more open to conversations about race and class and to consider the voices and needs of marginalized communities in the preservation process.

“Creamware” Dinner Plate, 1770s, Wedgwood, England

As a knockoff of porcelain, creamware symbolizes the integration of labor-saving techniques and division of labor, enabling rapid production of intricate patterns. This shift underscores the commodification of craftsmanship and the devaluation of labor, as workers were reduced to mere components in the manufacturing process. Additionally, the collaboration with artists like John Flaxman, as seen in other Wedgwood creamware marked a pivotal moment in design history, where design became separated from craftsmanship, laying the groundwork for modern design practices.

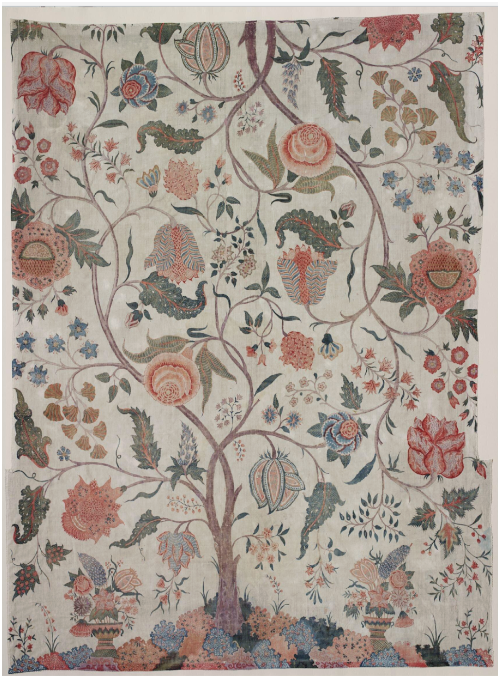

Chintz bed hanging

ca. 1725

Made in India for British export

Illustrates the impact of colonialism and industrialization on India's traditional craft practices. Made in India for British export, it showcases the intricate artistry of painted and dyed cotton textiles using mineral salts and wax-resist techniques. Its popularity among British consumers fueled demand for Indian textiles, yet the subsequent industrialization led to the decline of traditional craftsmanship in favor of cheaper, mass-produced alternatives, symbolized by the roller-printed furnishing fabric. This shift reflects the commodification and exploitation of India's artisanal heritage during the colonial period.

Morris and Co. Pine cabinet

1861

Phillip Webb and William Morris

Represents a cornerstone of the Arts and Crafts Movement, advocating for a return to pre-industrial forms of manufacturing and craftsmanship. Designed by William Morris and Phillip Webb, it embodies the movement's ethos of rejecting industrialization's impact on art and society. Crafted with deliberate irregularity and roughness, the cabinet evokes a sense of handmade authenticity and a longing for the artisanal traditions of the Middle Ages, contrasting sharply with the mechanized precision of mass production during the Industrial Revolution.

Poster for the Haripura Congress

1937

Nandalal Bose

Holds significance in promoting the re-establishment of a craft-based economy for India's independence during the Haripura Conference. Through handmade tempera paint on paper stretched on strawboard, Bose depicts craft as a physical process intertwined with the body and tools, emphasizing its role as an antithesis to industrialization. This poster underscores the historical and political origins of craft, advocating for its revival as a means to foster future creativity and independence.

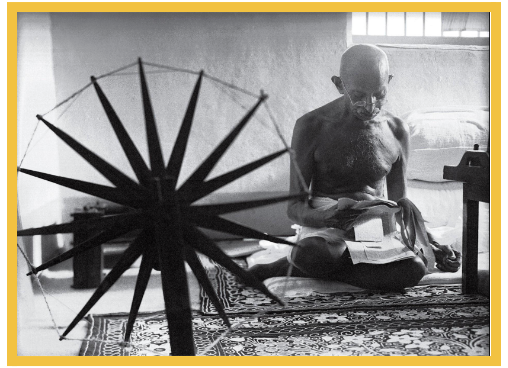

“Gandhi and the Spinning Wheel”

1946

Margaret Bourke-White

Significant in portraying Mahatma Gandhi's advocacy for Indian craft and economic independence during the independence movement. Gandhi is depicted surrounded by craft, wearing hand-woven cotton cloth, and seated near a Charkha spinning wheel, emblematic symbols of self-reliance and resistance to British colonialism. This image captures Gandhi's commitment to revitalizing indigenous craft industries as a means to achieve economic autonomy and national liberation.

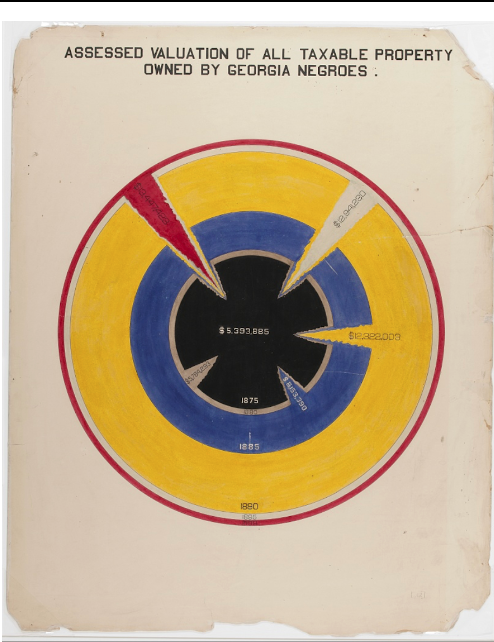

Poster from The American Negro Exhibit

W.E.B. Du Bois

1900

Holds historical and cultural importance as an early example of data visualization. It was designed with geometric precision to convey information about black property ownership, challenging prevailing narratives of racial hierarchy. As a writer and activist for African American rights, Du Bois used this graphic to present a more accurate portrayal of black life in America at the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle, aligning with his advocacy for social justice and equality.

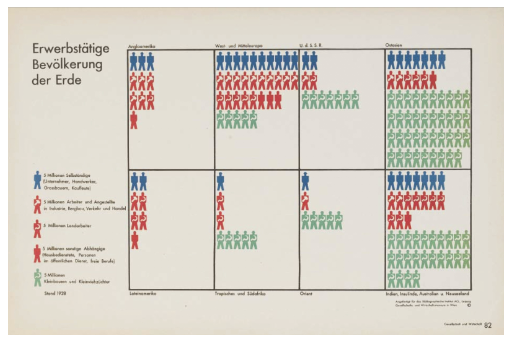

Information graphic (“Working Population of the World”)

Gerd Arntz

1930

an example of the Isotype system, which aimed to communicate complex information across boundaries of race, class, and time. Using pictorial symbols and primary colors, Arntz conveys statistics of laborers from different parts of the world, demonstrating a level of legibility and universality in his work. This visual language was developed during a period of optimism and progressivism, reflecting efforts to create an international language amidst geopolitical challenges.

The “White Room”

Eliot Noyes and Associates

1964

reflects IBM's transition into incorporating design principles into their computer systems in the 1960s. Noyes' emphasis on modern design, with neat and tidy aesthetics, primary colors, and controlled space, aimed to make computers more approachable and less intimidating during a period of societal anxieties surrounding new technologies. This design strategy helped shift perceptions of computers from complex and unwieldy machines to sleek and user-friendly tools.

“Think” film

Ray and Charles Eames

1964

was significant for its innovative approach to representing computer operations. Through multi-screen projections of dynamic images, lights, and colors, the film aimed to immerse viewers in the experience of being inside a computer, portraying computers not just as objects but as entities with a sense of magic and mystique. This approach differed from the controlled and orderly design of computer systems by Noyes, offering a more whimsical and engaging perspective to make computers more appealing to the public.

Cybersyn Opsroom

State Technology Institute and Gui Bonsiepe

1971-73

represents a socialist approach to design aimed at facilitating social welfare programs during a tumultuous period in Chile's history. The opulent interior design, featuring lush chairs and a space-age aesthetic, combined with abstract, modernist data displays on screens, reflects an effort to utilize design to create a cooperative management style and open up data processing systems that transcend class boundaries, emphasizing the integration of design and ideology in societal development.

Model T

Ford Motor Co.

1908-1927

llustrating the evolution of automobile design and production, representing the transition from custom-built luxury goods to mass-produced vehicles. Its utilitarian design and efficient construction techniques democratized car ownership, shaping access to mobility and reflecting broader cultural shifts in transportation. This transformation prompts reflection on who has access to cars and who doesn't, raising questions about class, race, and mobility in society.

KdF Wagen (“Strength Through Joy Car”)

Germany

1938

Symbolizes the intersection of design, propaganda, and nationalism during the Nazi regime. Through strategic design choices such as streamlined modernist aesthetics and imagery evoking speed and progress, the brochure was meticulously crafted to promote patriotism and consumerism among the German populace. By employing visual elements that glorified German engineering prowess and emphasized themes of national unity and strength, it exemplifies the manipulation of design aesthetics to convey ideological messages of German superiority and societal cohesion under the Nazi regime.

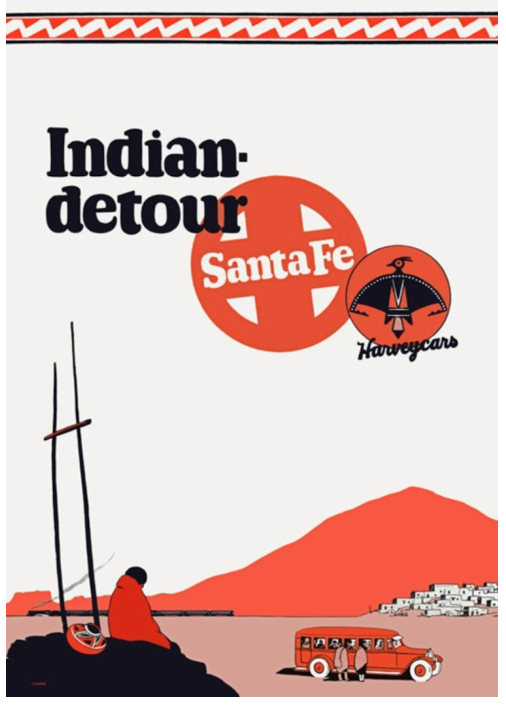

“Indian Detour”

Fred Harvey Co.

1920s

Highlights the role of automobile tourism in shaping cultural perceptions and reinforcing racial hierarchies. By offering controlled encounters with Native individuals within a commodified setting, it underscores how car travel facilitated the exoticization and exploitation of indigenous cultures while reinforcing colonial power dynamics

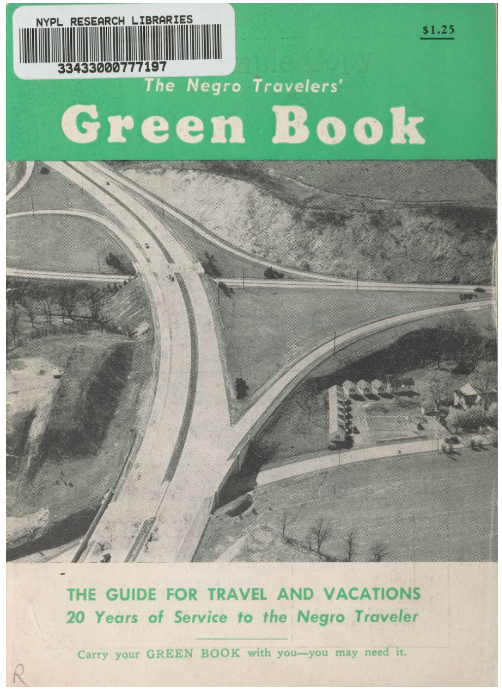

The Green Book

Victor H. Green

1936-1967

Served as a crucial tool for Black automobile tourists navigating the segregated landscape of pre-Civil Rights America. As a travel guidebook listing safe accommodations and resources, it represents a form of resistance to racial discrimination and a testament to the importance of design in facilitating access and safety for marginalized communities.

Maria

Rose B. Simpson (Santa Clara Pueblo)

2014

Chevrolet El Camino with custom bodywork to resemble Pueblo blackware, embodies the fusion of indigenous cultural identity with contemporary automotive design. Simpson's car art challenges conventional notions of car aesthetics and ownership, reclaiming automotive spaces as sites of cultural expression and empowerment for indigenous and gender-queer communities. The fusion of Spanish and indigenous culture =within the artwork reflects the complex relationship between colonial history and contemporary identity.

Nightingale-Brown House (1792), College Hill, now part of Brown University

Preserved beautifully, costs millions of dollars National landmark status (only one of a few in the country) This is a typical example of what we think about when we think about preservation

General Archive of the Indies, Seville, Spain, 1784/1785

Led to documentaries of America’s past being institutionally differentiated from documentaries of Europe’s past (separating them). The wood and layouts in the archives – built on the back of slave labor. The person creating the design is complicit with the history. The function of the detail of design is a function to ensure the archive’s validity and authority within the arrangement of archives, we can gleam what they find important

No Records Reggie Black, Yinka Shonibare

Examples of creative preservation efforts that help us to change how we see these histories and stories

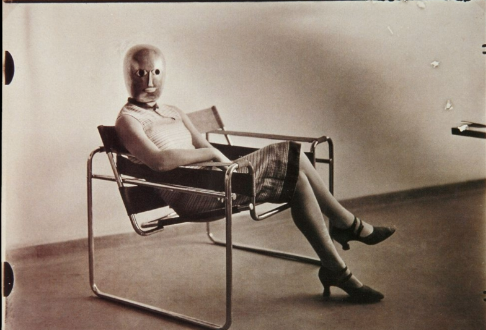

Photograph of Liz Beyer or Ise Gropis at the Bauhaus

(chair by Marcel Breuer)

Erich Consemüller

1926

Lis Beyer's confident posture within the chair symbolizes the integration of human presence into the purifying space of modernist design, blurring the boundaries between body and object. The image prompts reflection on the relationship between gender, identity, and designed environments, highlighting themes of control, efficiency, and the erasure of individual identity within the utopian ideals of modernist aesthetics.

ILZRO House (Diana Harrison in the Kitchen)

Marc Harrison

1972

Showcases a modernist approach to residential design with a strong emphasis on accessibility and functionality for individuals with physical impairments. Through features like countertops with adjustable heights, multiple sinks, and specialized storage drawers, the house demonstrates a commitment to creating inclusive and barrier-free environments. It exemplifies the integration of design and social advocacy by prioritizing usability and adaptability for those with mobility challenges.

Rebirth Garments and Radical Visibility Zine

Sky Cubacub

2014-

A manifestation of radical visibility and social advocacy within the realm of fashion. This clothing line specializes in gender non-conforming wearables and adaptive fashion for people with disabilities, while the accompanying zine features stories, artwork, and manifestos that celebrate disability pride and challenge societal norms of beauty and identity. Together, they foster a sense of community and empowerment through fashion activism, aligning with the broader movement towards disability justice and intersectional activism.