Craft Guild Presentation

1/21

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

22 Terms

Hello, everyone! Thank you for being here today.

My name is Mandy Bass.

Today, I want to share not only the stories behind my artwork but also the creative process that brings these pieces to life.

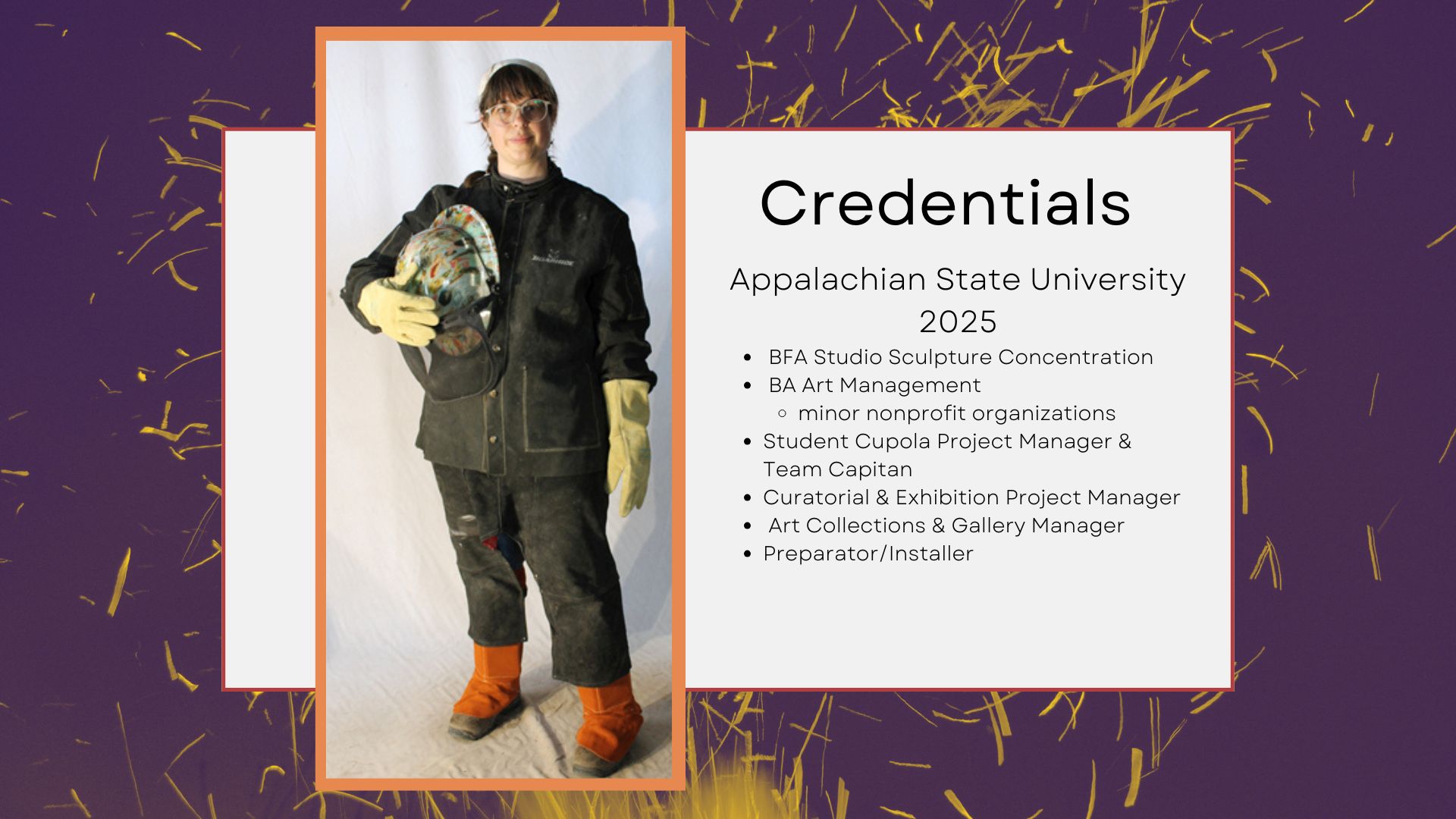

I’m a recent grad from Appalachian State University, where I developed a studio practice focused on sculpture, concentrating on foundry and casting.

During my time at App State, I built an iron furnace a project that gained me recognition from the National Confernce on Centamory Cast Iron Art & Practices, curated exhibitions, and managed the Student Union’s art collections and gallery. Now I currently work as a contract Preparator, installing artwork for various exhibitions.

Just a content warning: The following slides contain images of deceased birds. Please feel free to step out of the room as you see fit.

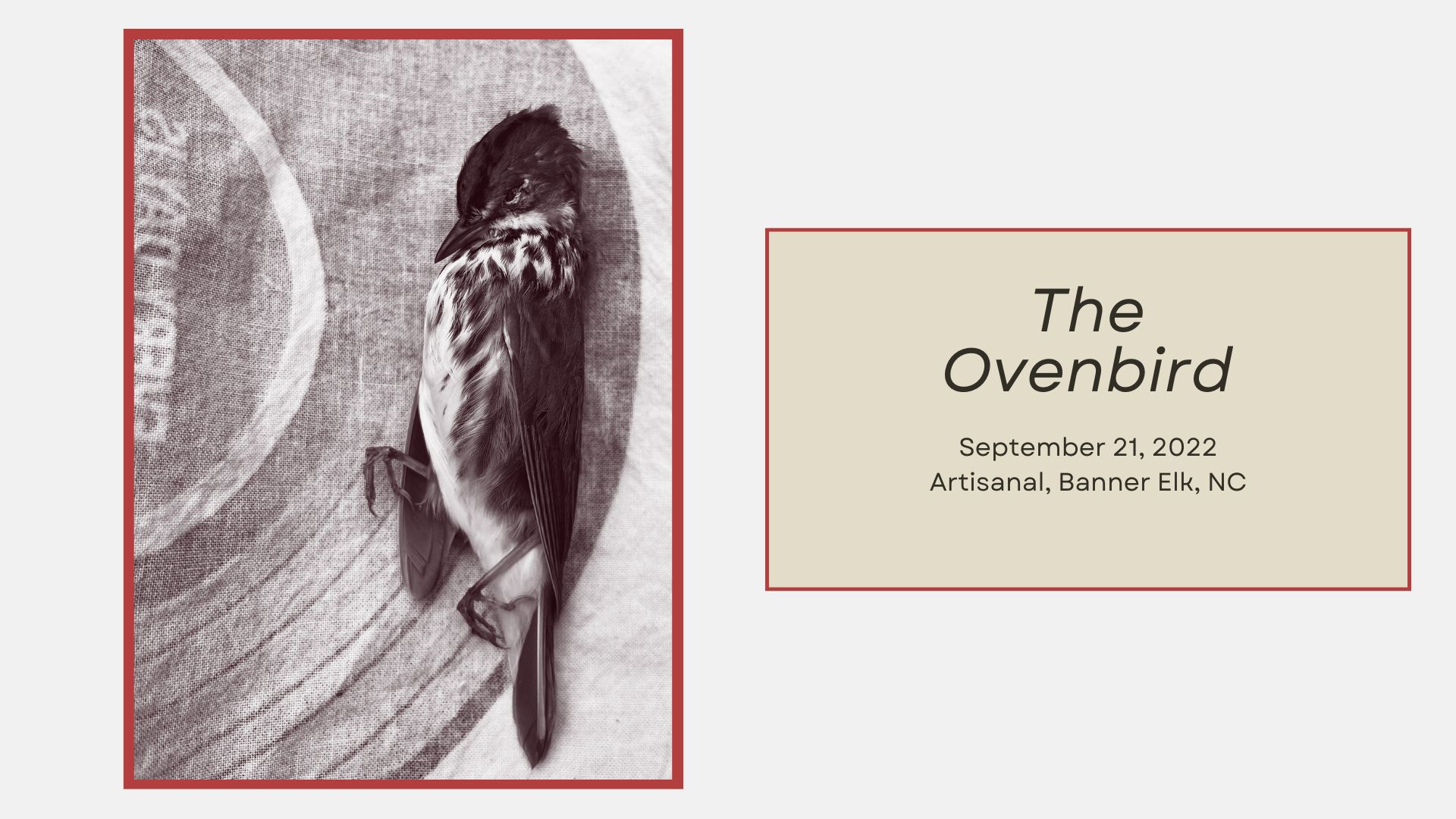

A defining moment in my practice was witnessing an ovenbird collide with a window—an experience that made me acutely aware of the vulnerability of these creatures within built environments.

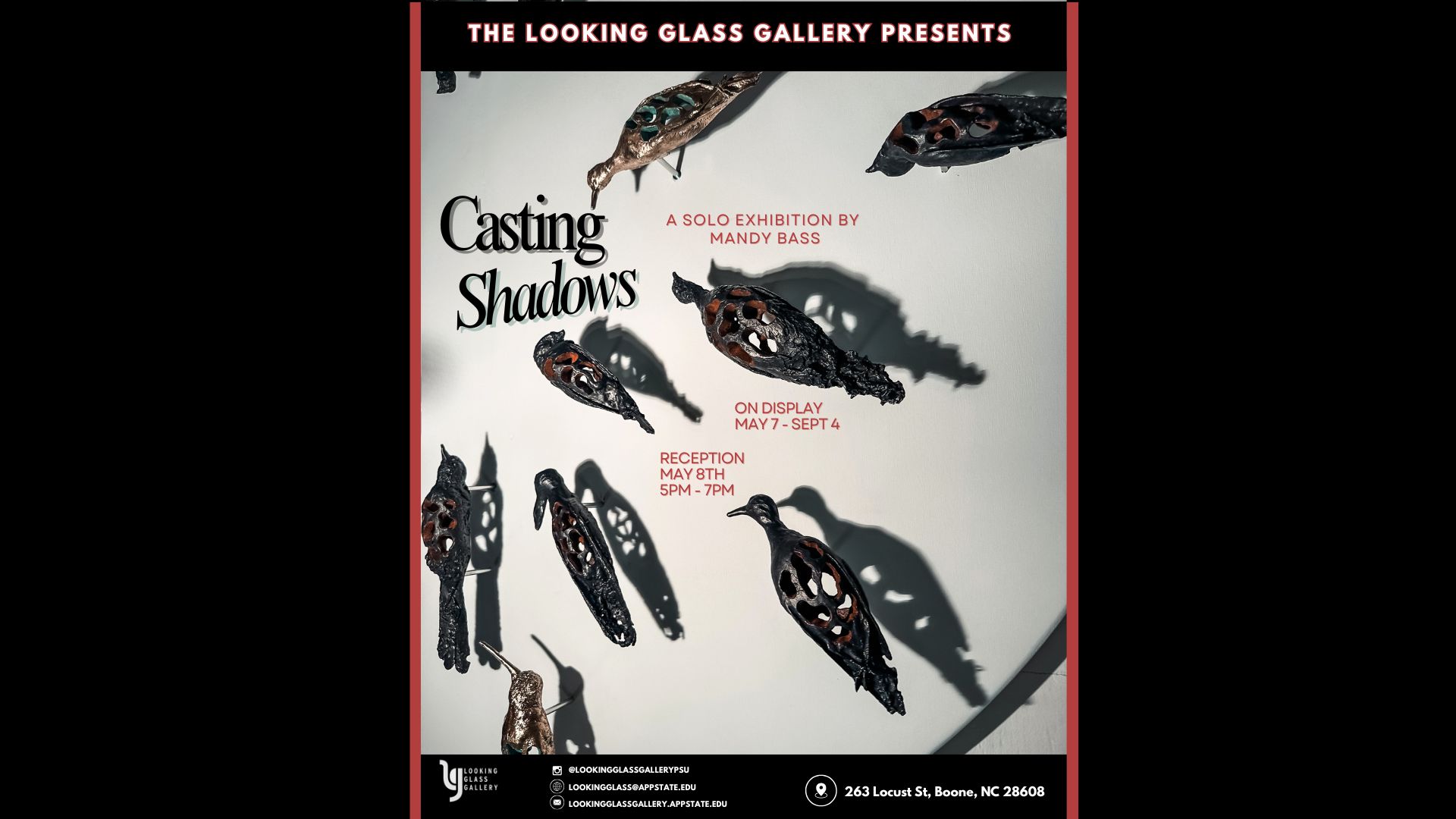

My most recent body of work, Casting Shadows, now on view at the Looking Glass Gallery in Boone, NC, explores the complex relationship progress and ecological loss, focusing on the impact of human activity on vulnerable species and their habitats.

Combining traditional casting techniques with modern 3D scanning, the works in this exhibition are crafted from glass, metal, and cement. These materials reference the dangers posed by manmade structures to wildlife, emphasizing the fragility of species and the spaces they navigate. Found plastics are integrated into the sculptures as a reflection of both my own consumption habits and the persistent human presence in natural environments

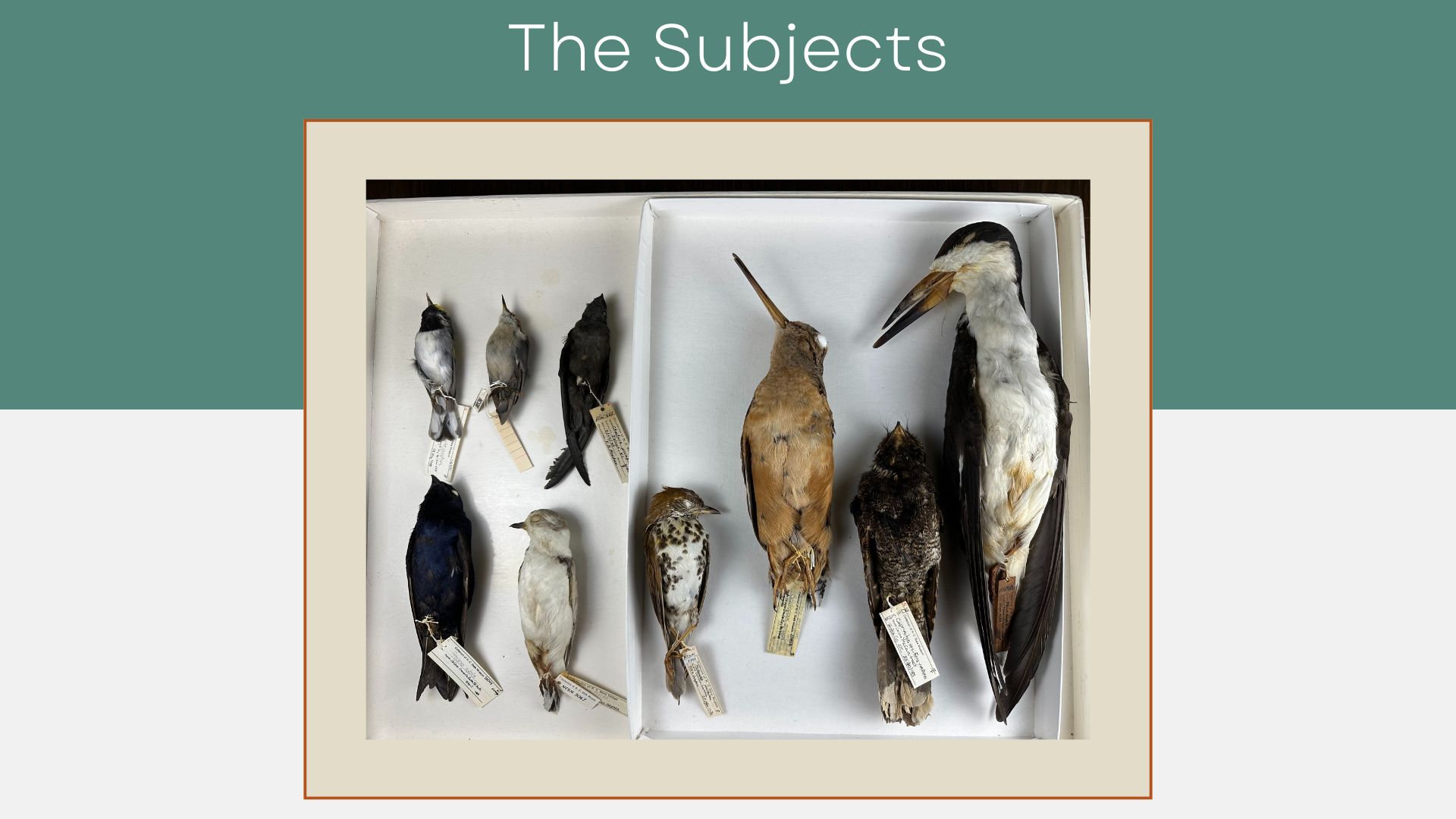

For this project, I collaborated with the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh, NC. The provided me access their bird collections, including specimens of endangered and extinct species.

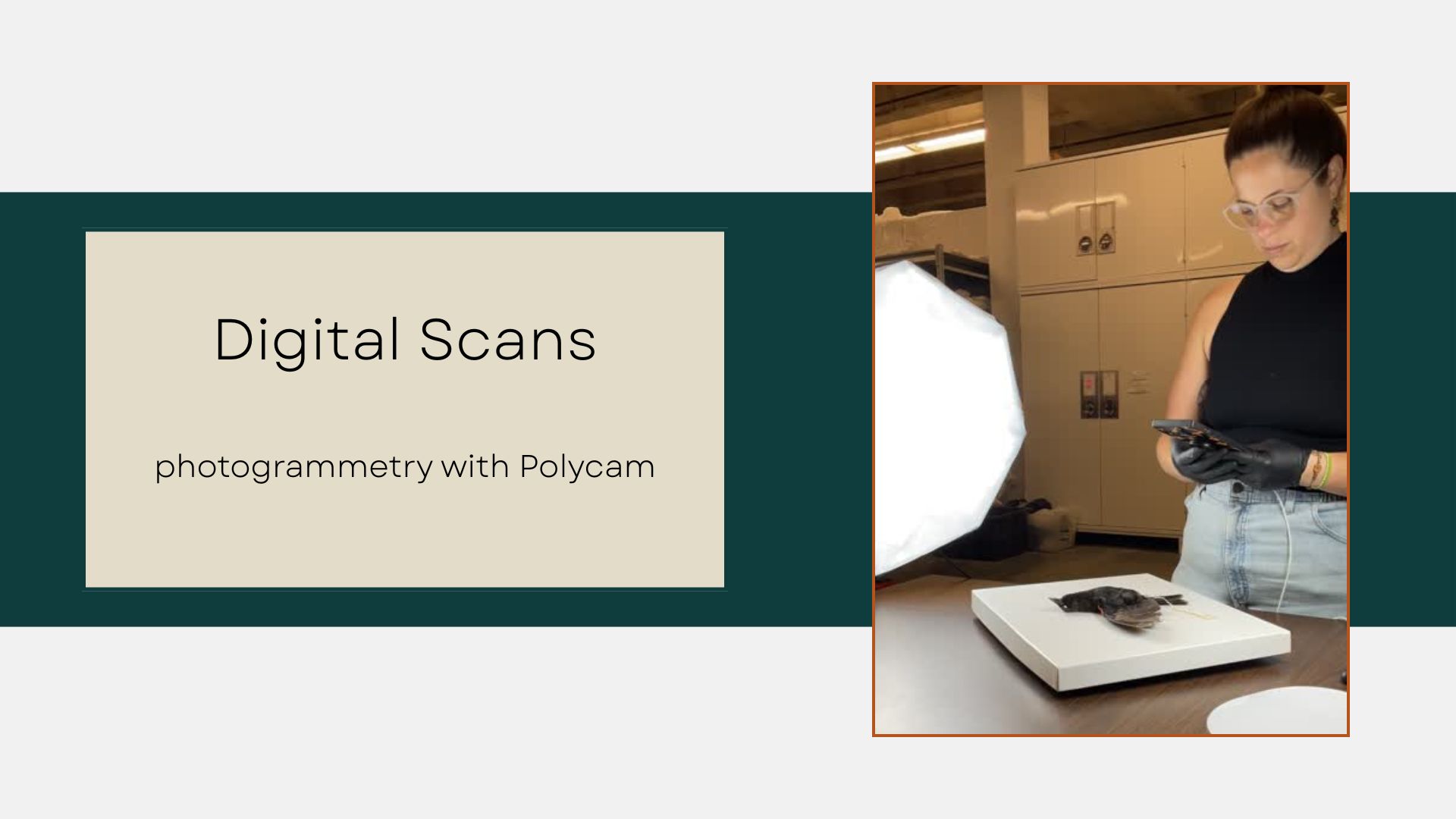

The project begins by 3D scanning bird specimens using photogrammetry. Right now I use my phone with an app called Polycam. It works well but I hope to transition to more advanced technologies of 3 D scanners to get even more detailed images.

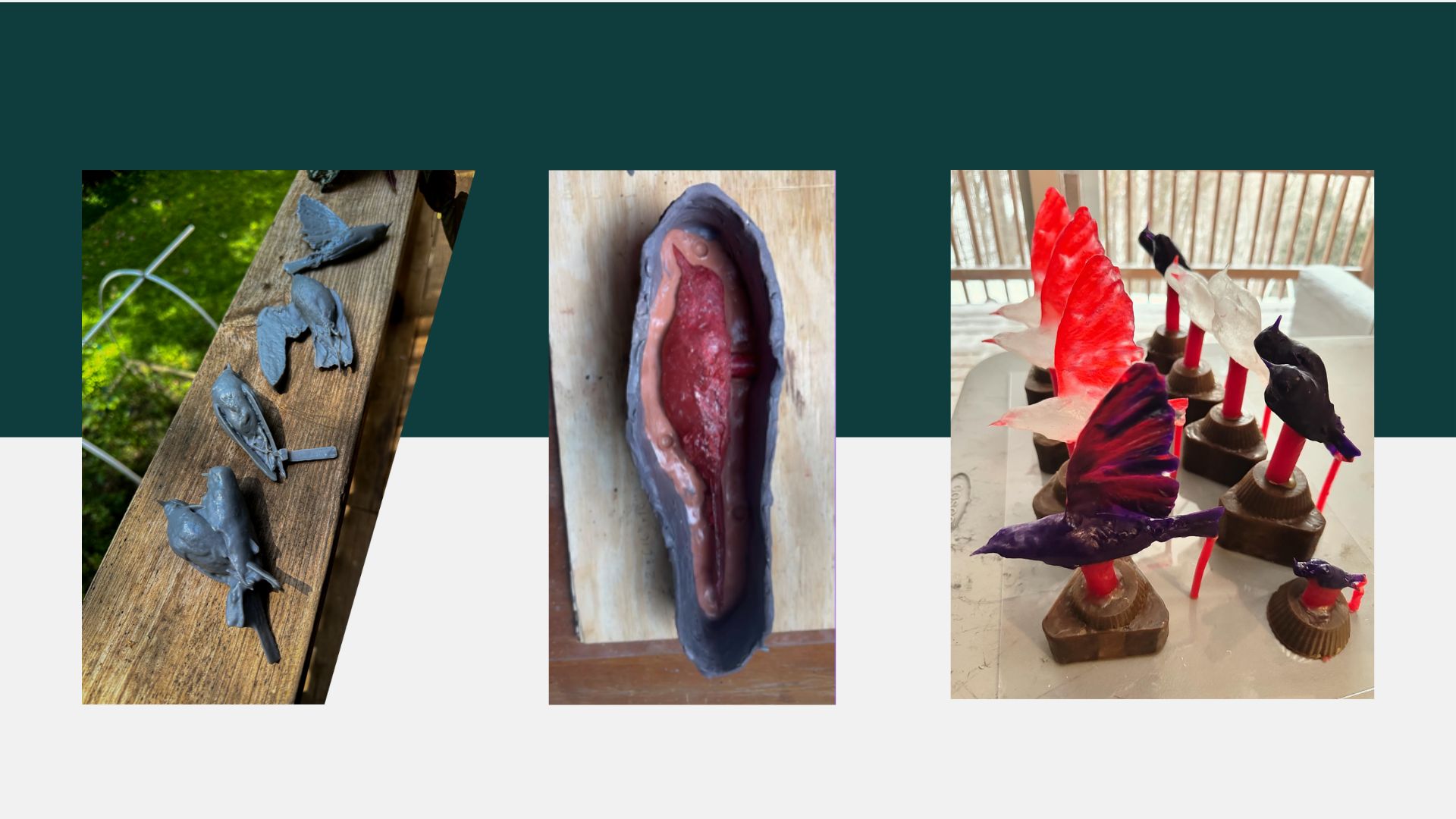

After scanning the specimens, the resulting detailed 3D images are refined using modeling software to prepare each bird for 3D printing.

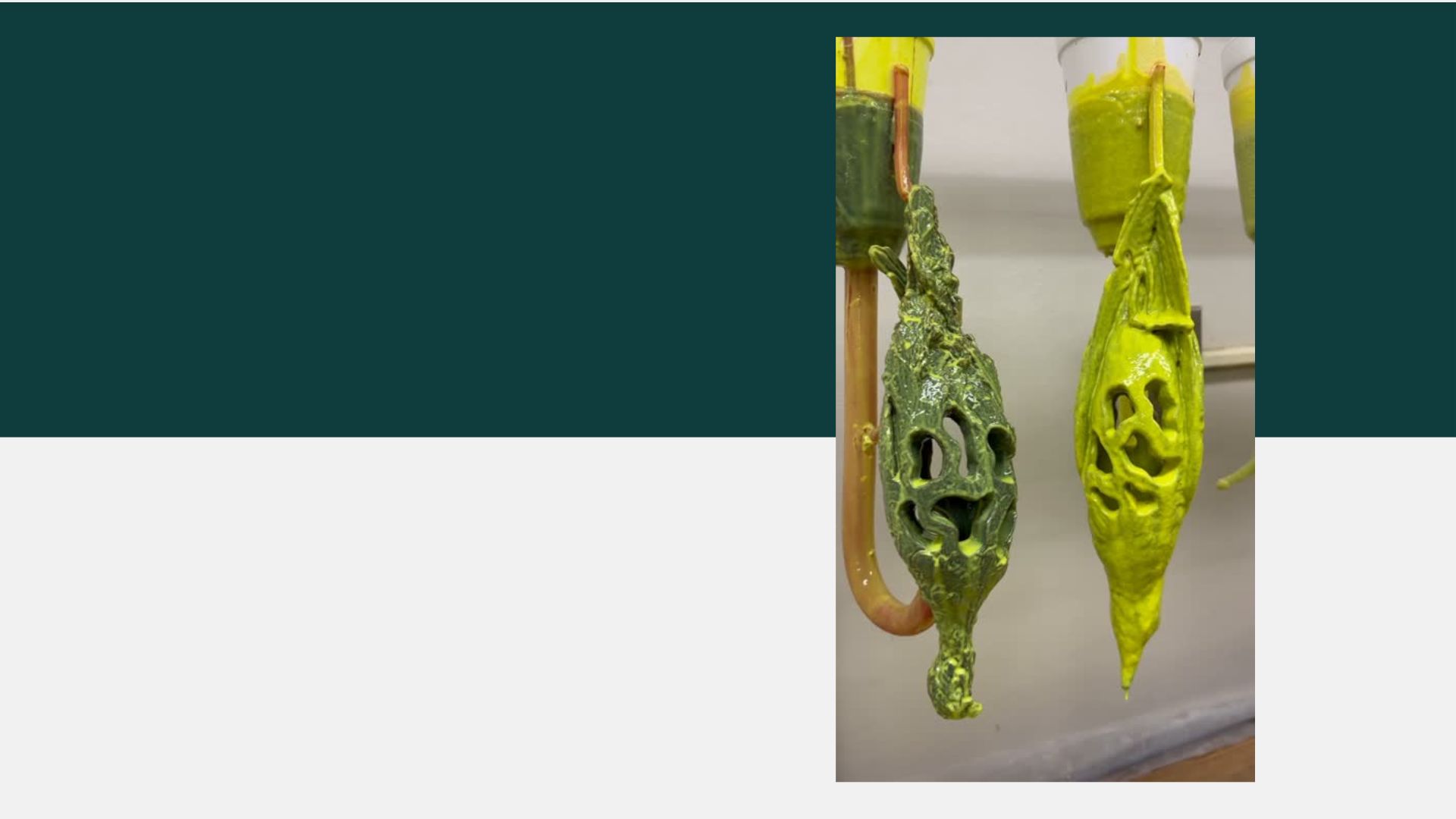

These printed forms either printing in resin or PLA , are then used to create molds for for lost wax or as direct burnouts

For some of the sculptures in my exhibition I used the Kiln cast glass technique where glass is melted in a kiln for extended periods of time. My firing schedule is about 5 days.

Using this process the printed resin form were burned out leaving empty cavity for molten glass to flow into and fill

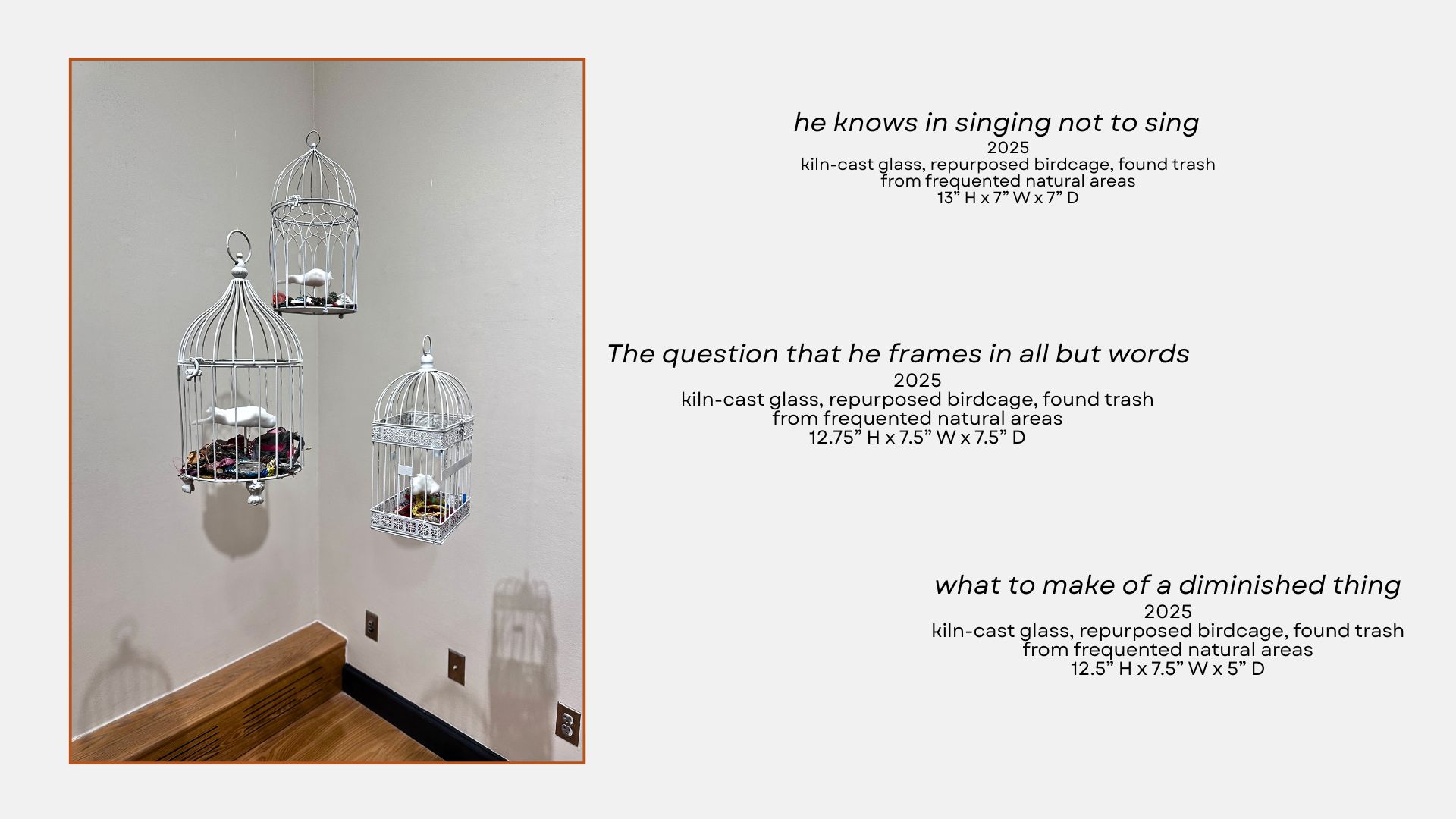

These pieces’ each named after a line from the Rober Frost poem, The Oben bird’ symbolize nature’s fragile purity alongside humanity’s irreversible impact.

Inspired by the Ovenbird, the double-headed forms—created by imperfections in the 3D scanning process—reflect the unintended consequences of human encroachment.

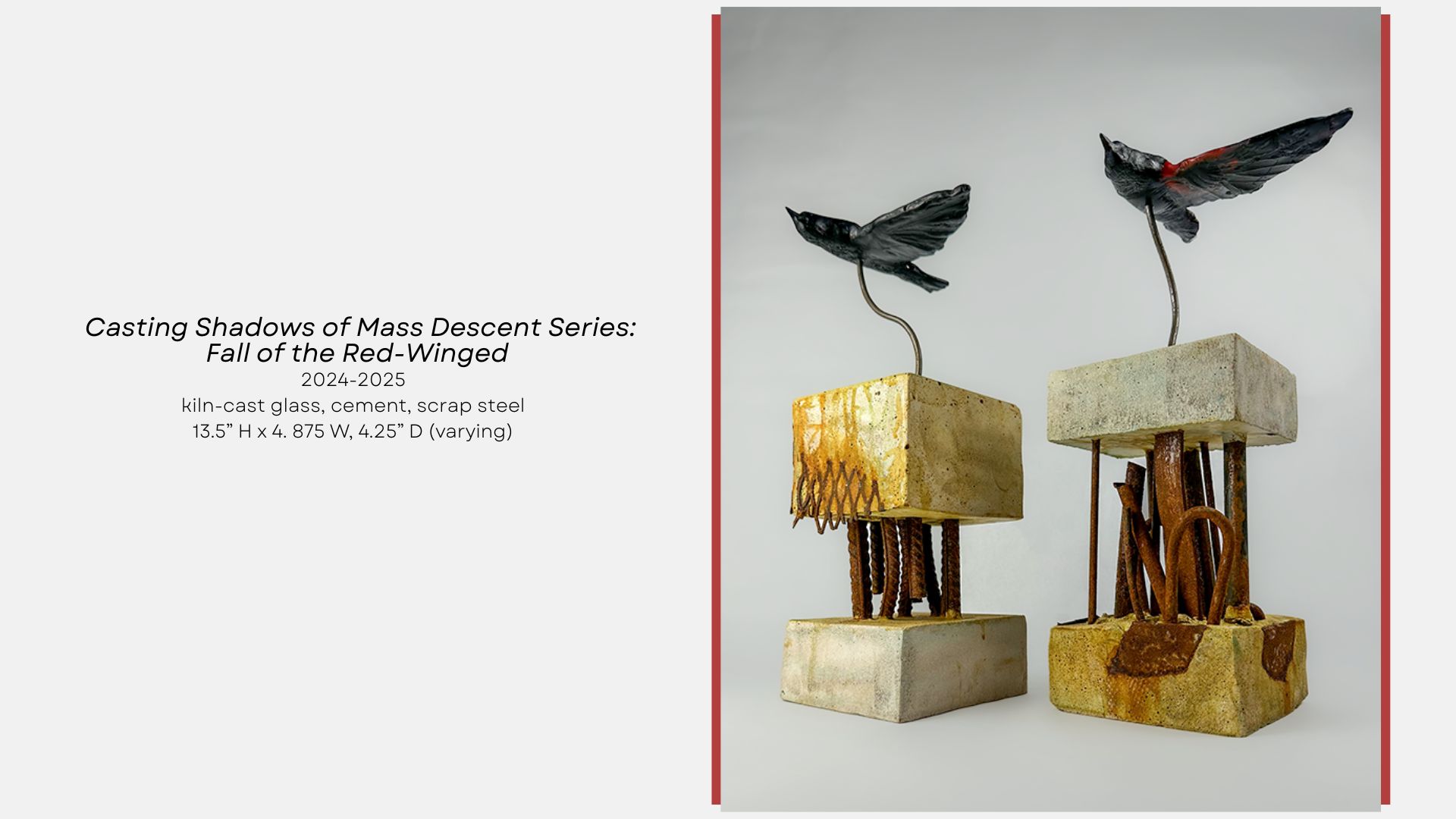

Casting Shadows of Mass Descent reflects on a real event in which thousands of Red-winged Blackbirds fell from the sky—an unsettling incident that underscores the fragility of life and the often-overlooked consequences of human activity

The other method I used was lost wax, used for my iron and bronze pieces. Multiple hollow wax forms were created using silicone molds made from the 3D prints, and then I carved negative spaces into each of the birds. These shapes remind me of organic forms found in nature.

Once carved, I used the ceramic shell mold-making process for these intricate forms due to their complexity. For forms of this size, it’s best to apply approximately eight layers, building up to about ¼ inch of material.

The main challenge with this was that the small negative spaces in the forms tended to close up before I could apply enough layers. Investment could be a good alternative for these forms, but the ceramic shell process is necessary for pouring iron because investment alone cannot withstand the high temperatures.

My solution was to use half the usual number of ceramic shell layers, which also helped conserve the limited material available.

To restore the stability typically provided by the full amount of layers, I invested the shelled pieces. After melting out the wax and heating to a high enough temperature to vitrify the shell without over heating the investment, a fine line, I was ready for the iron pour.

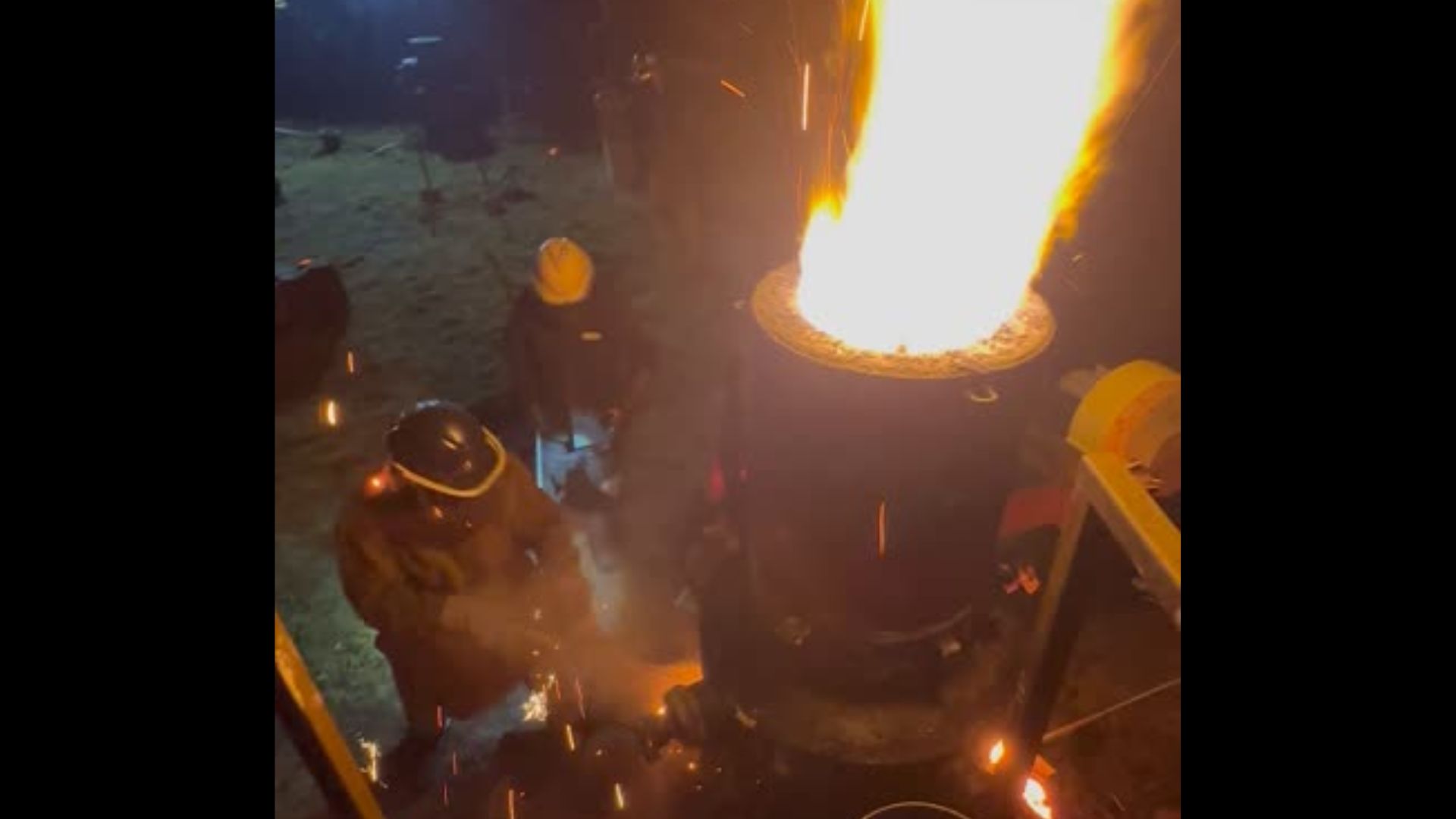

Now this is my favorite part.

How many of you have ever been to an iron pour?

For those who haven’t experienced one, I highly recommend it.

This is the view from a charging platform. Pouring iron is one of the most exciting processes I can imagine, and its collaborative nature fosters an incredibly strong and supportive community.

But before filing the molds with molten iron, I constructed a kiln capable of sustaining elevated temperatures to keep the molds hot enough for optimal metal flow and detail retention. The investment material acted as an insulating barrier, slowing the cooling rate and reducing thermal shock, which led to more consistent results and improved surface detail in the final castings.

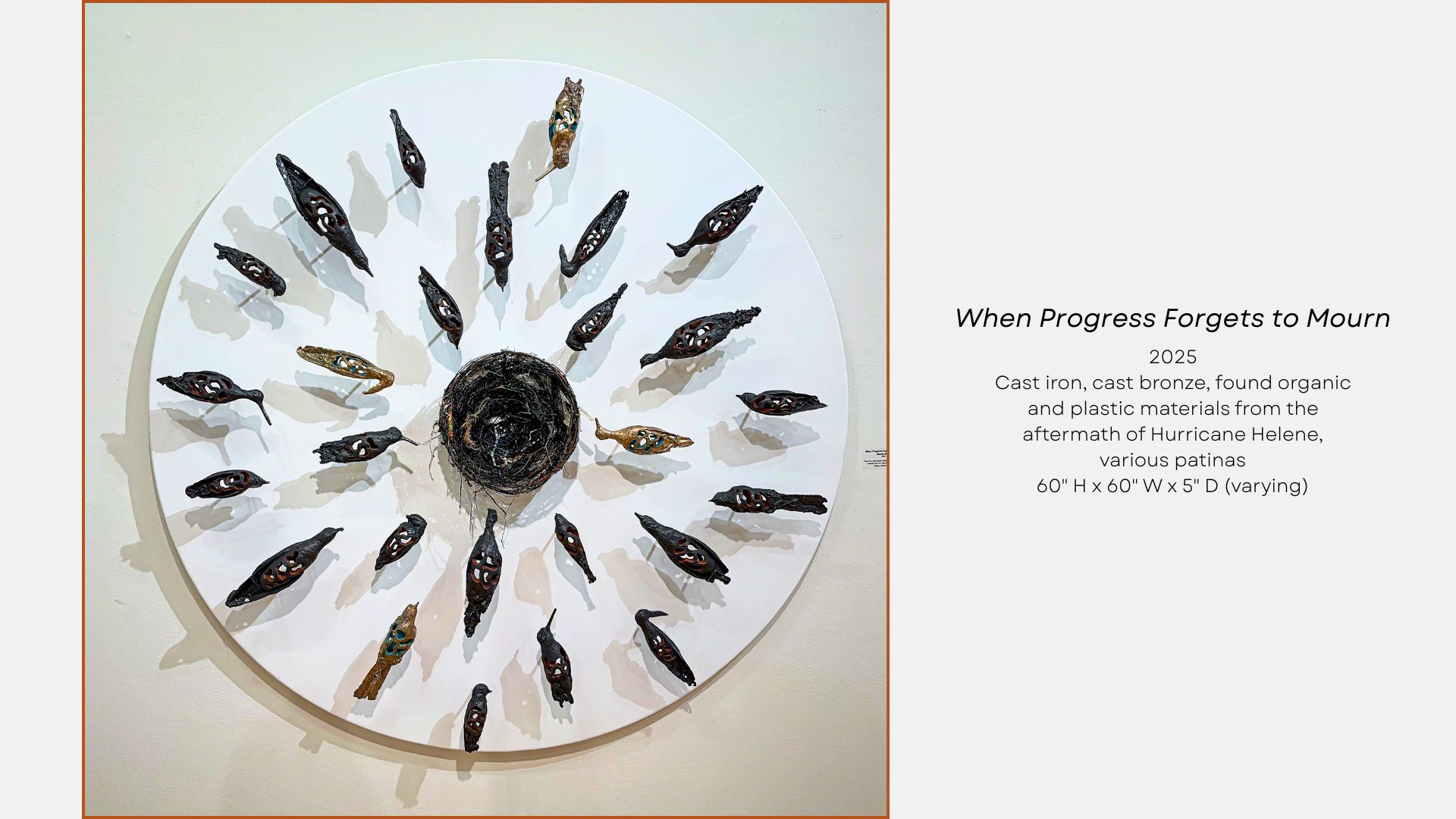

The centerpiece of my exhibition, When Progress Forgets to Mourn, confronts the loss left in the wake of human progress. It addresses species decline, climate change, and the enduring traces of human presence over time.

This work holds space for the species lost, the damage unseen, and the natural histories erased by human progress, inviting viewers to pause within that unresolved tension. Mourning here becomes an essential act of care—a necessary step toward moving forward with intention.

Casting Shadows blends art and scientific research to deepen the narrative around environmental issues. Rather than offering solutions, the exhibition stands as a record of loss, disruption, and the uneasy intersections between human expansion and ecological loss.

If you’d like to learn more about the project, please scan the QR code. It will take you to a website featuring profiles for each bird in the exhibition, along with an expanded discussion of the concepts based on my research.

Thank you again for your time and attention. I’m happy to answer any questions you may have.