RISD THAD H102 MIDTERM SPRING 2024

1/82

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Lectures, Readings, Key Images - Information from midterm study guide by Arlie & key image information from Koji, and a little of my notes https://docs.google.com/document/d/1vCTod3J94QQxYRnfIFjCbmEyAzGvqQnfahuUy9lcJmk/edit?usp=share_link note: did not include all information for some stuff because too long

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

83 Terms

Lecture 1 Good Design?

Lecture questions universality, focusing on historical iterations of mid-twentieth-century modernist "Good Design"

Examines exclusionary practices based on criteria like gender and race in the pursuit of universality

Lecture 2 Art History and the Islamic World

Overview of major themes in visual and architectural traditions of the Islamic world

Examination of how these themes and artworks are understood within the predominantly Euro-American discipline of Art History

Historical context provided for the singling out, categorizing, and systematic study of a diverse range of artworks

Lecture 3 Calligraphy, Geometry, Ornament

Encompasses various art forms such as embellished Qur’an folios, ceramics, metalwork, and architectural masterpieces

Examines the representation of the divine through writing and ornamentation

Explores the reflection of the divine in the geometric ornament, a long standing feature in Islamic arts

Lecture 4 Perspective and the Organization of Architectural Spaces in Persian Painting

Art production played a crucial role in international diplomacy among the gunpowder empires

Gifts like illustrated books, carpets, and ceramics were exchanged to normalize relationships and demonstrate cultural superiority

Persian painting introduced an alternative spatial imagination, diverging from the dominant European linear perspective

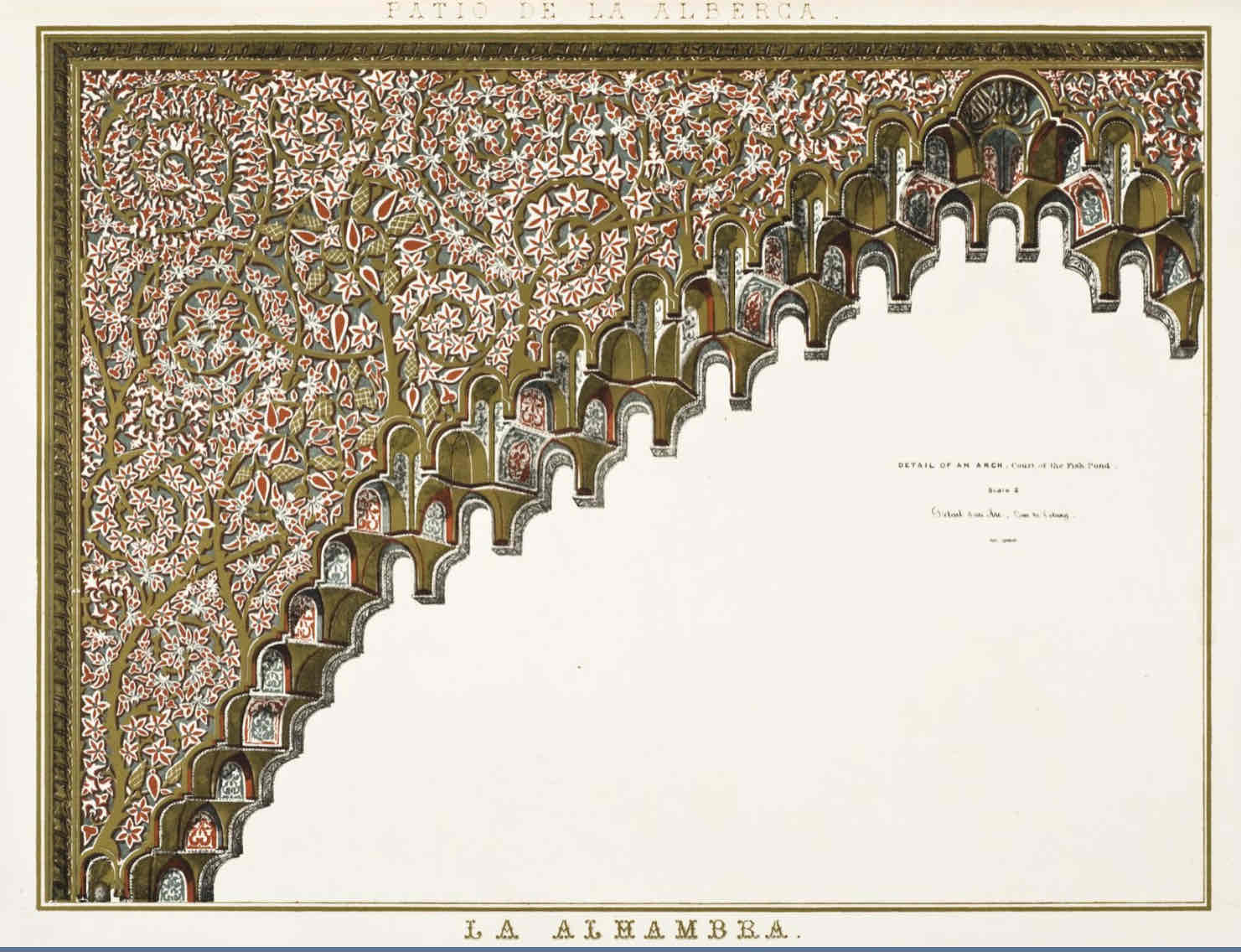

Lecture 5 Architecture in al-Andalus

Nearly 800 years of Muslim caliphate rule led to a significant artistic legacy in Islamic Spain

Examination of the Iberian Peninsula as an ideal location for cross-cultural interaction among Islamic, Jewish, and Christian traditions

Lecture 6 Orientalism and the Era of World Exhibitions

Examines the Exposition universelle de Paris in 1889 and its connection to Europe's quest for colonial dominance

Highlights the role of presenting the world as an exhibition, aligning with Orientalist logic

Lecture 7 Textiles: 40000 Years of Women’s Work

Archaeological evidence globally indicates women's involvement in fiber processing, spinning, weaving, and garment-making

The argument suggests that these activities, being close to home, allowed women to contribute to the economy while caring for children

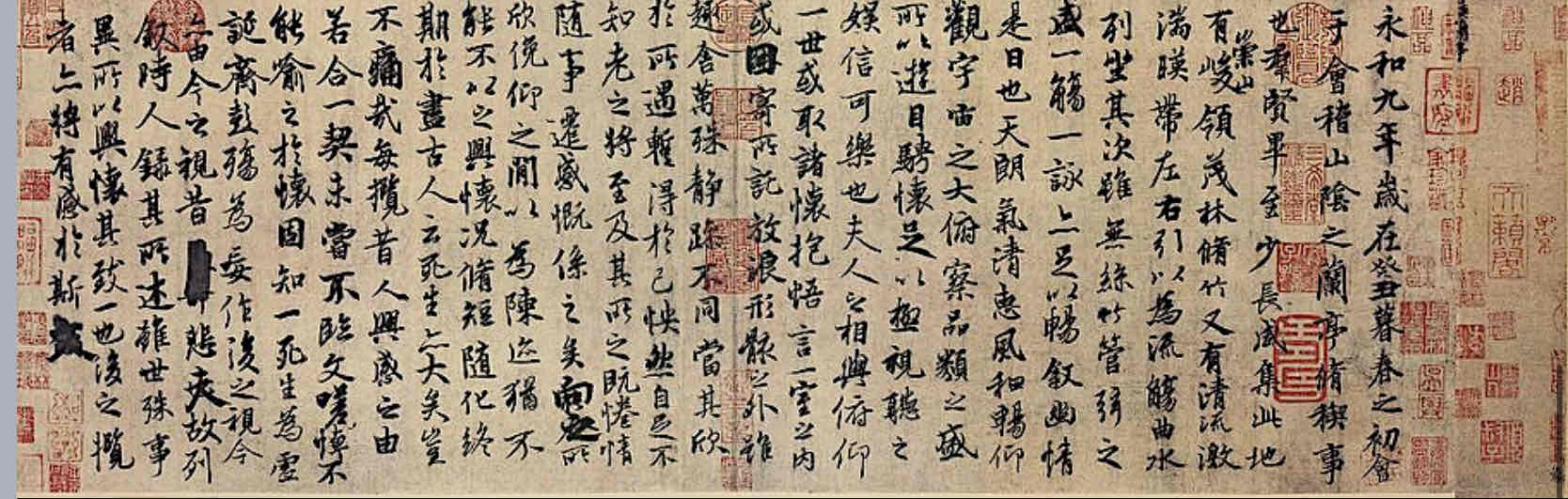

Lecture 8 Chinese Writing and Calligraphy

Challenges the notion of writing solely as a tool for recording spoken language

Highlights continuity between ancient scripts (oracle bone inscriptions), traditional ink calligraphy (shufa 書法), books, and contemporary artistic practices

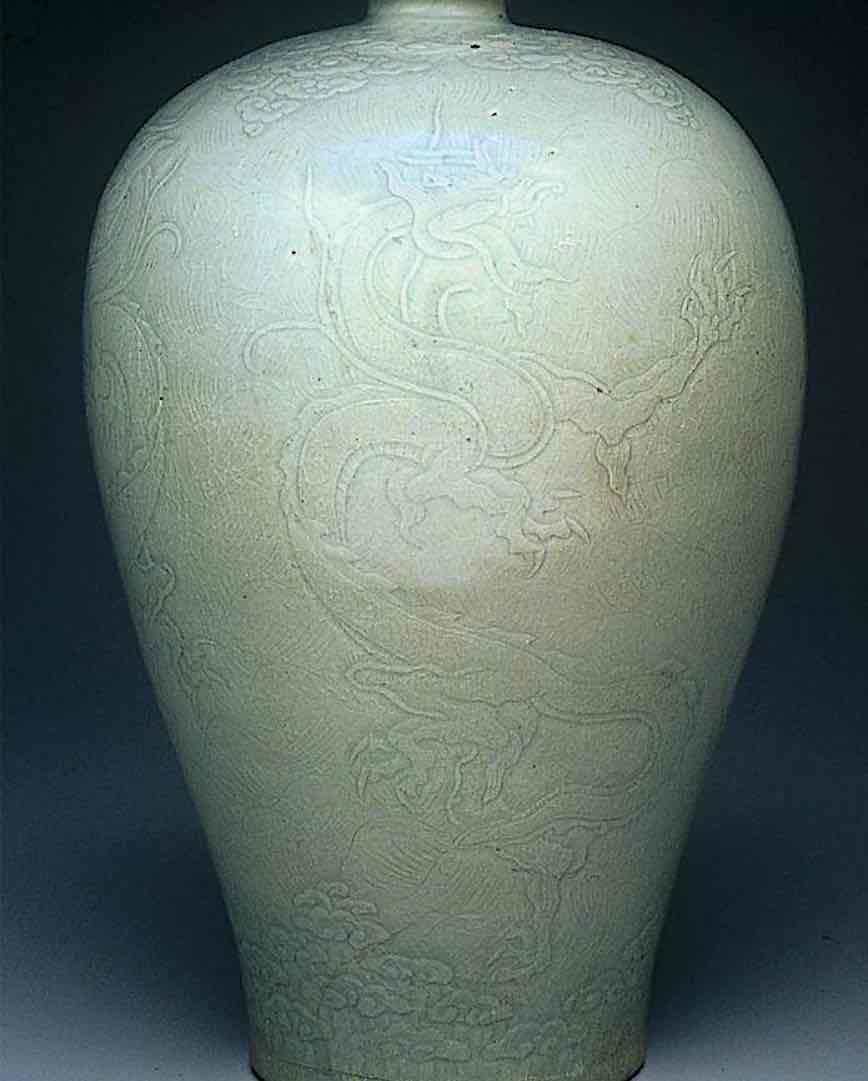

Lecture 9 Porcelain: the Worldwide Blue and White Craze

The export of porcelain, especially blue and white ware, spurred Chinese maritime exploration and power

Examines the global impact of Chinese porcelain on the arts

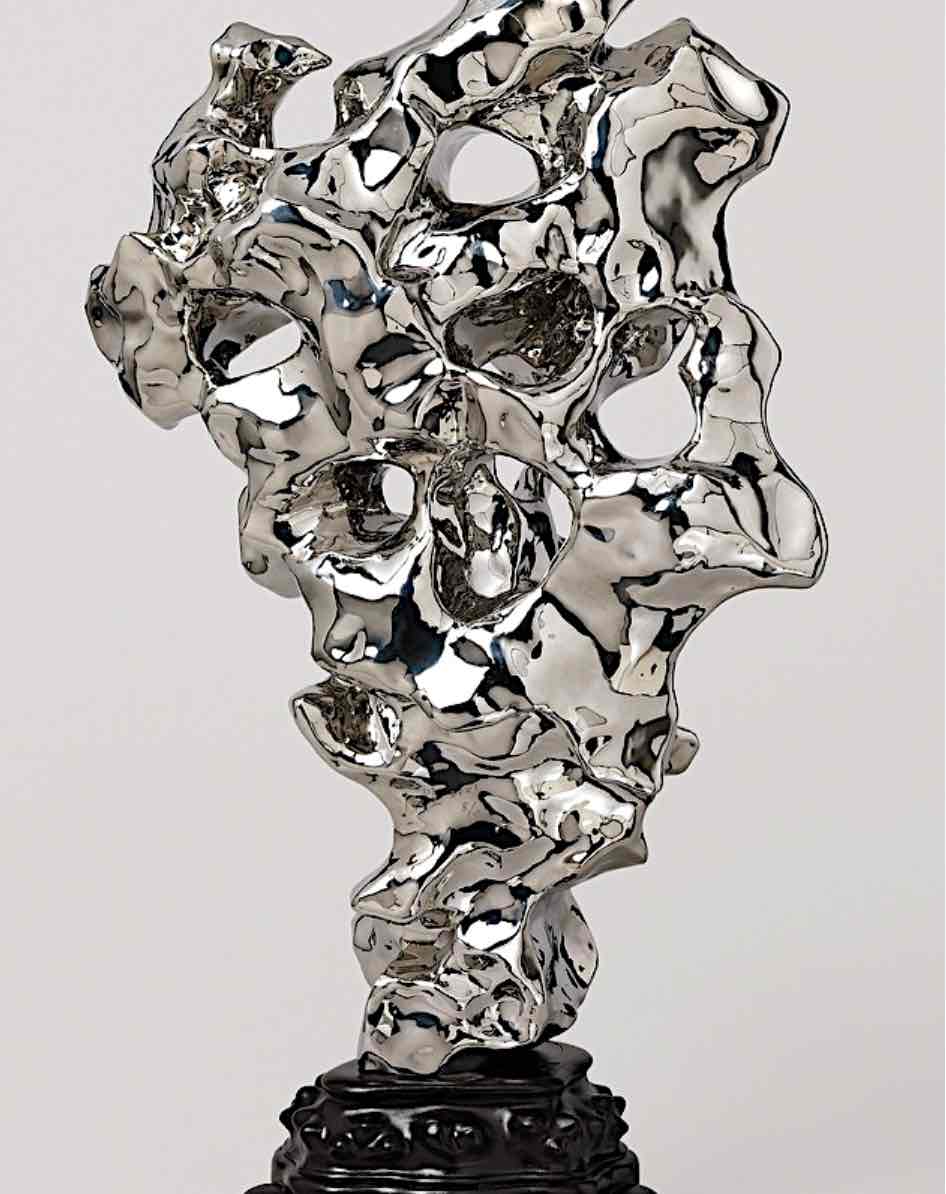

Lecture 10 Nature: from Landscape Painting to Chinese gardens

Despite mountains and rivers being considered divine residences, landscape painting's popularity grew around the 10th century, coinciding with urbanization and nature exploitation

Economic growth and increased urbanization in later centuries led to city gardens where mountains and rivers were miniaturized for urban elites' enjoyment

Lecture 11 Designing the Cosmos

Explores how translating something universal, like the position of stars, reveals cultural and design influences on perceptions of the universe

Lecture 12 Relics, Reliquaries, and Pilgrimage

The lecture focuses on reliquaries, objects designed to hold and validate relics

Examines the impact of popular pilgrimages on buildings holding relics

Considers the role of design and architecture in the long history of devotion, tourism, and celebrity

Lecture 13 The Medieval Cathedral as “Total Artwork”

Architecture is experienced not only visually but also through the entire body

The concept of a building as a "total artwork" gained popularity in design movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries

Reading “What do we mean when we say ‘Islamic art’? A plea for a critical rewriting of the history of the arts of Islam”

The texts explore the complex and contested nature of Islamic art, addressing the tension between the perceived unity and diversity within this artistic tradition. Scholars discuss the historical projection of a monolithic Islamic identity, influenced by Eurocentric perspectives. They question the validity of the term "Islamic art" and propose alternative concepts such as "the arts of the lands of Islam." The impact of Western modernism on the interpretation of Islamic art, including its classification as traditional, is examined. The texts call for a reevaluation of terminology and a more nuanced understanding of the diverse visual cultures within the Islamic world.

Reading “The Qurʾan, Calligraphy, and the Early Civilization of Islam”

The text provides an overview of the evolution of Arabic calligraphy in early Islamic civilization, spanning from the pre-Islamic era to the tenth century. They explore the emergence and transformation of Arabic script, with a focus on the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, highlighting the role of calligraphy in Qur'an recording and the establishment of a standardized visual identity. Additionally, the manuscripts commissioned by political elites and scribes demonstrate the connection between cultural, religious, and political influences. The tenth century witnessed significant changes in calligraphy styles and manuscript production, reflecting societal shifts, increased demand, and the systematization of Qur'anic sciences.

Reading Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years. Women, Cloth, and Society in Early Times

Delves into the significant role of women in early societies, particularly focusing on their involvement in textile production and other crafts. The transition from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic era marked a shift towards settled life and agriculture, leading to the development of technologies like weaving and pottery. Women played a central role in these developments, managing household tasks and crafting while men ventured outside the community for additional resources. The book explores the intricate craftsmanship of Neolithic fabrics, the communal work and entertainment among prehistoric European women, and the emergence of urban civilization in Mesopotamia. It also highlights the importance of environmental factors in shaping the development of different types of looms and textiles.

Reading “Mysterious Heavens and Chinese Classical Gardens”

Delves into the intricate world of classical Chinese garden design, drawing from the author's firsthand experience visiting gardens in Shanghai and Suzhou in 1980. It contrasts Chinese garden aesthetics with those of Japan, highlighting the evolution from private sanctuaries for masters and their families to spaces accommodating various activities reflecting human nature and self-expression. Influenced by Daoist and Confucian philosophies, these gardens embody themes of natural environments for hermits, fantasies of deities, and ethical values. Central to their design are concepts like dongtian, representing a hierarchical Daoist paradise, and fantastic rocks reflecting Daoist cosmology.

Reading "Medieval Modernism and the Origins of Gothic"

Presents a multifaceted examination of Gothic architecture, primarily through the perspectives of Trachtenberg and Fernie. Trachtenberg proposes alternative labels like "Medieval historicism" and "Medieval modernism" to categorize Gothic architecture, emphasizing its ideological underpinnings alongside its functional aspects. Fernie engages in a debate over the relevance of traditional style labels, advocating for their continued use. He explores the significance of architectural elements such as rib vaults and pointed arches in the evolution of Gothic architecture, particularly highlighting the role of structures like Saint-Denis. The text discusses the complexities of patron-architect relationships and the development of innovative structural techniques seen in buildings like Noyon and Laon cathedrals. Additionally, it considers the conceptual perspectives of historicism and modernism in Gothic architecture, acknowledging varying interpretations. Finally, the text reflects on the symbolism of architectural styles in art, illustrating how Gothic architecture came to symbolize the "new" in contrast to Romanesque structures.

Bee Wing Lace Neckpiece

Luci Jockel (JM 16)

2021

Resonates with the lecture's exploration of design as a cultural practice that extends beyond aesthetics and purpose, reflecting cultural attitudes and values (in this case, environmentalism, as well as referring to the tradition of lace making in Rhode Island).

Side chair model DCM

Ray and Charles Eames

1946

While the chair’s functionalist approach reflects a historical context of providing practical solutions for a mass audience, it’s categorization as “good design” by western designers underscores the inherent limitations and potential exclusions associated with “universal” design claims.

Ulm School of Design student furniture

Max Bill, Hans Gugelot, and Paul Hildinger

1954

Signifies the commitment to practical and universal design principles while prompting critical reflection on the limitations and inclusivity challenges associated with universality. These works encapsulate the ethos of the Ulm School while contributing to discussions on the universal nature of design.

Stool rattan and fabric cushion

Isamu Kenmochi

1963

Exemplifies the embrace of functionalist and "universal" design approaches by other cultures. Notably, it integrates the Japanese cultural tradition of rattan weaving, showcasing a fusion of functionality with distinct cultural elements during this period.

Tripé de Ferro chair

Lina Bo Bardi

1950

Similarly embraces a functionalist and "universal" design approach while integrating other cultural elements, specifically Brazilian cattle ranching. This chair exemplifies the fusion of functionality with distinctive Brazilian cultural motifs, showcasing design's capacity to incorporate local traditions within the context of “good design”.

The Great Mosque of Xi’an

Early Ming Dynasty

As an Islamic mosque in China, it illustrates the diversity and cultural exchange within the Islamic world and serves as a challenge to the restrictive classification of "Islamic Art" by Western Orientalists, which tends to narrowly focus on Arabian, Persian, and similar influences.

Earring

11th-12th century CE

The critical aspect of any object’s inclusion in the MET’s display of Islamic Art lies in the museum's intent and interpretation. If the museum consciously aims to present a more comprehensive and diverse picture of Islamic art by including objects that challenge preconceived notions, the earring becomes a tool for broadening perspectives. However, if its display reinforces stereotypical views without addressing the complexity and variety within Islamic art, it may perpetuate the issue of pigeonholing Islamic art as one type of art.

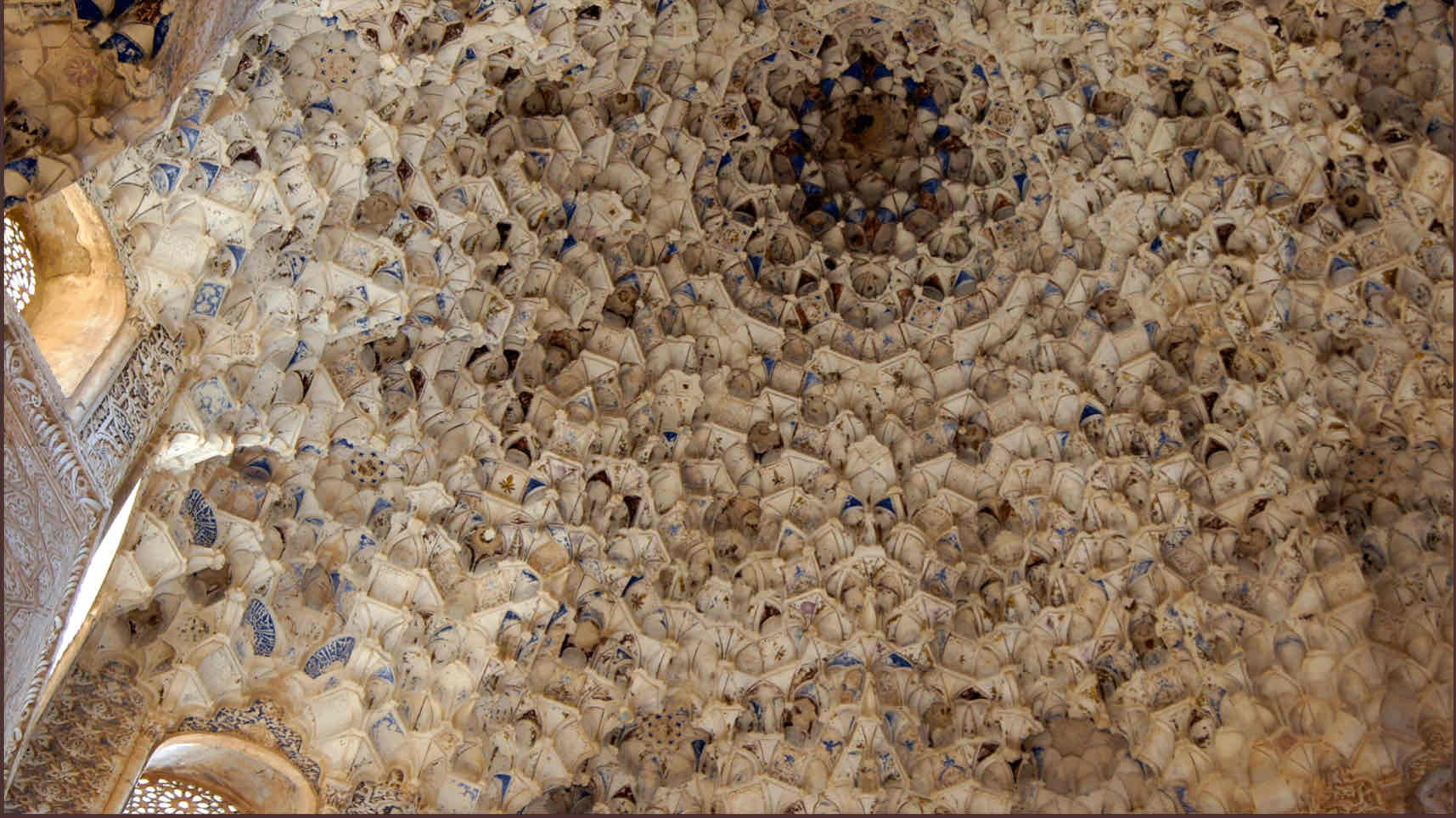

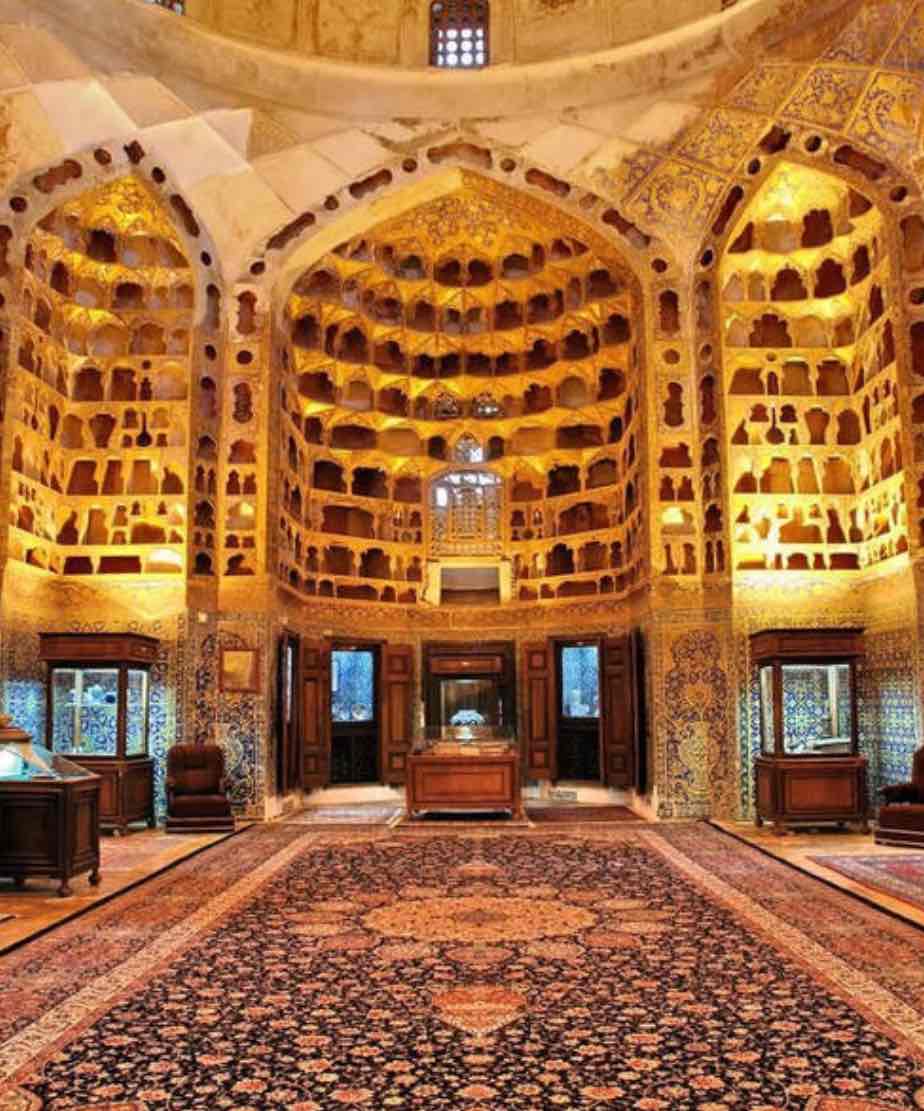

Muqarnas Dome

12th-13th century

A highly calculative mathematical piece that apprehends the divine through the artistic immersion viewers experience. Ornamental art is devalued by the west for its association to “traditional”

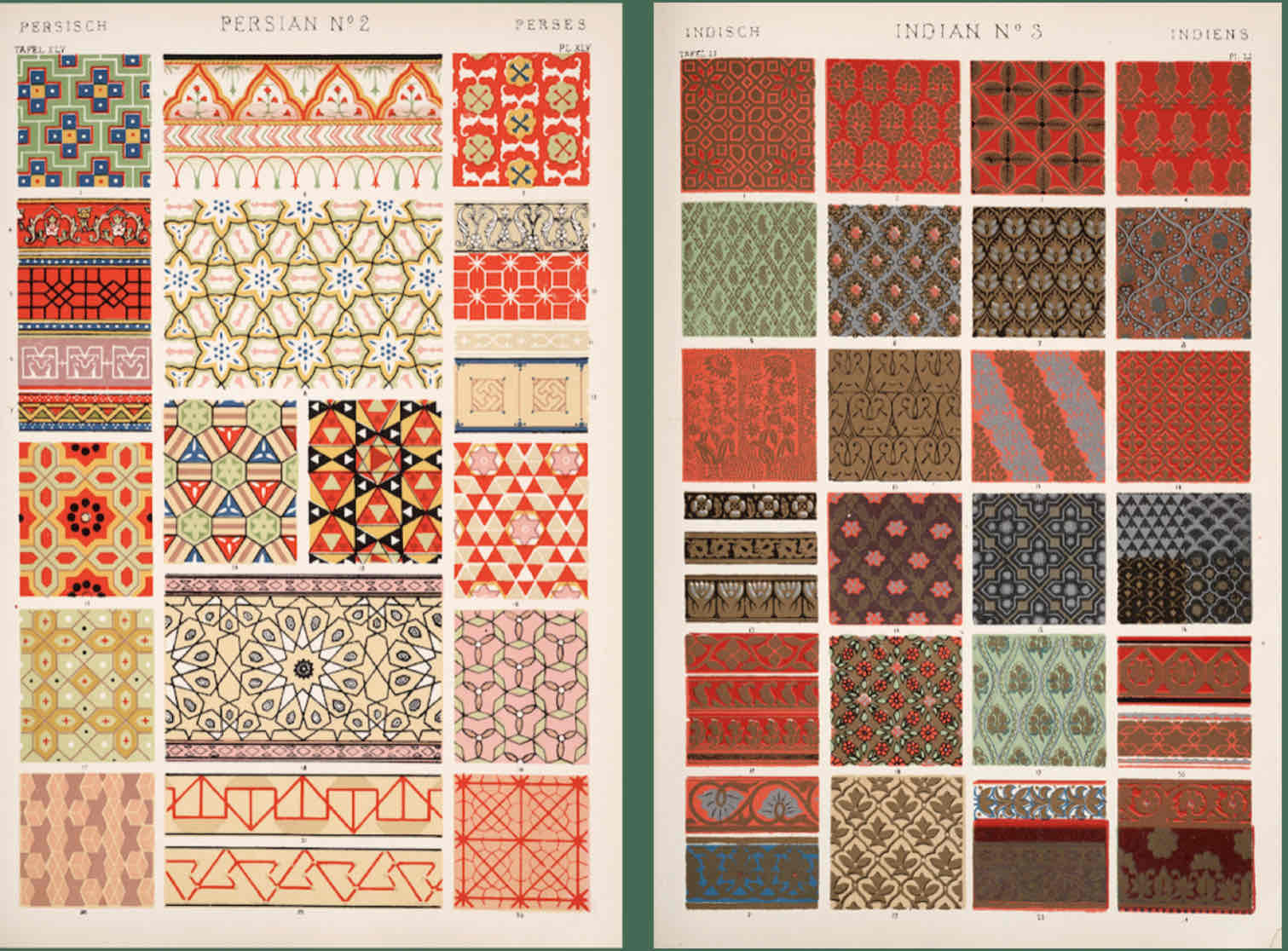

The Grammar of Ornament, Persian No.2 and Indian No.3

Owen Jones

1865

Typifies the Western tendency to compartmentalize Islamic art. Reflects hierarchical views, categorizing non-western modes of design as inferior to the western

1851 Great Exhibition temporary building

Owen Jones

1851

Symbolizes Western attitudes toward tradition and reason, reflecting a focus on monumental structures and grand exhibitions as markers of artistic achievement. This aligns with the lecture's discussion on the prioritization of elite architectural works and the shaping of Western perspectives in categorizing art

Calligraphic Roundel

Late 16th-early 17th century CE

Represents the emphasis on calligraphy, geometry, and ornamentation in various art forms within Islamic traditions. The inscription, one of the ninety-nine names of God, showcases the significance of calligraphy as "the geometry of the soul."

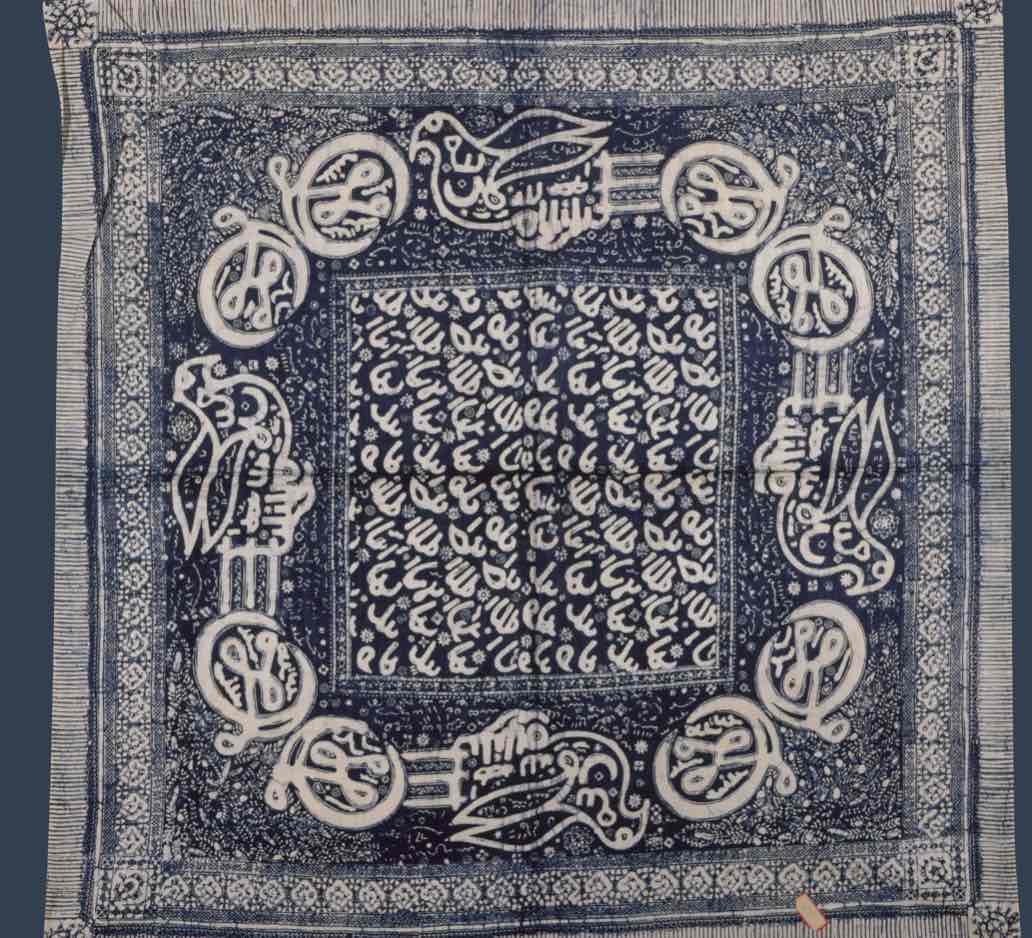

Iket Kepala (Man’s Headcloth)

ca. 1850-1900 CE

A representation of Southeast Asian culture where Islamic imagery is integrated into traditional textiles. The headcloth features pseudo-Arabic words and the name Allah (SWT), showcasing the synthesis of Islamic, Hindu, Buddhist, and animist influences.

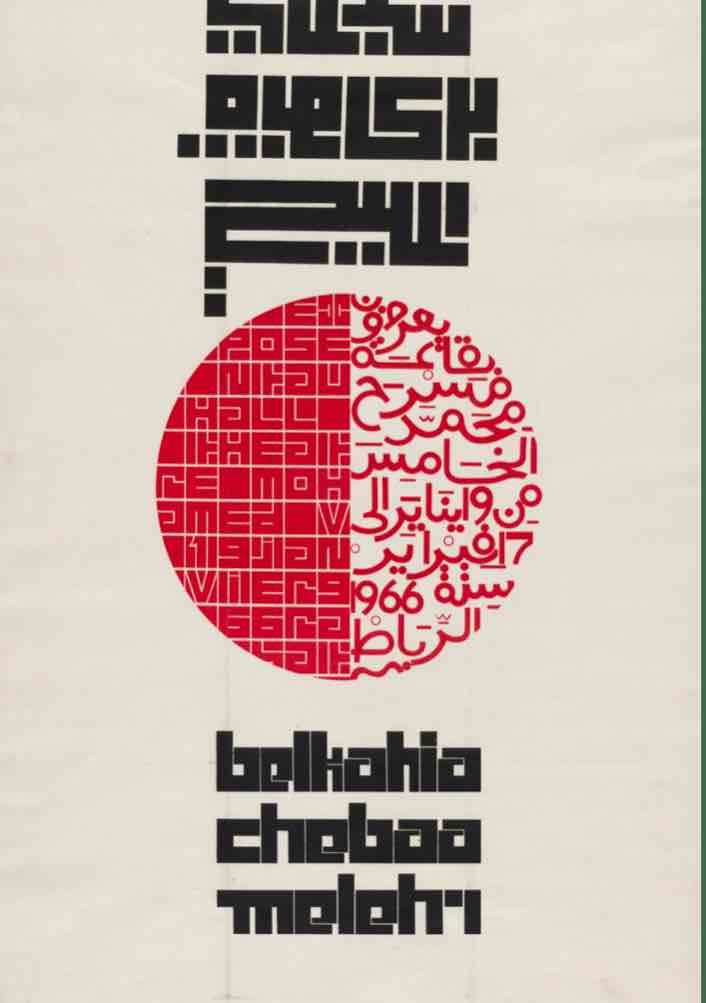

Poster exhibition of Farid Belkahia

Mohamed Melehi

1966

Offers a contemporary interpretation of script through geometric abstraction and Kufic script. Created by the Moroccan artist Mohamed Melehi, the piece reflects a freestyle approach, blending modern aesthetics with traditional elements.

Qasr Al-Mshatta façade (detail)

Umayyad period, 8th-century CE

Features 28 equal triangles, showcasing the importance of ornamentation in Islamic art as a complex relationship of forms. The detailing reflects a profound engagement with geometry and design, highlighting the lecture's point that these geometric elements don't have a finite endpoint but can infinitely evolve, in a mirror to the creation of the world.

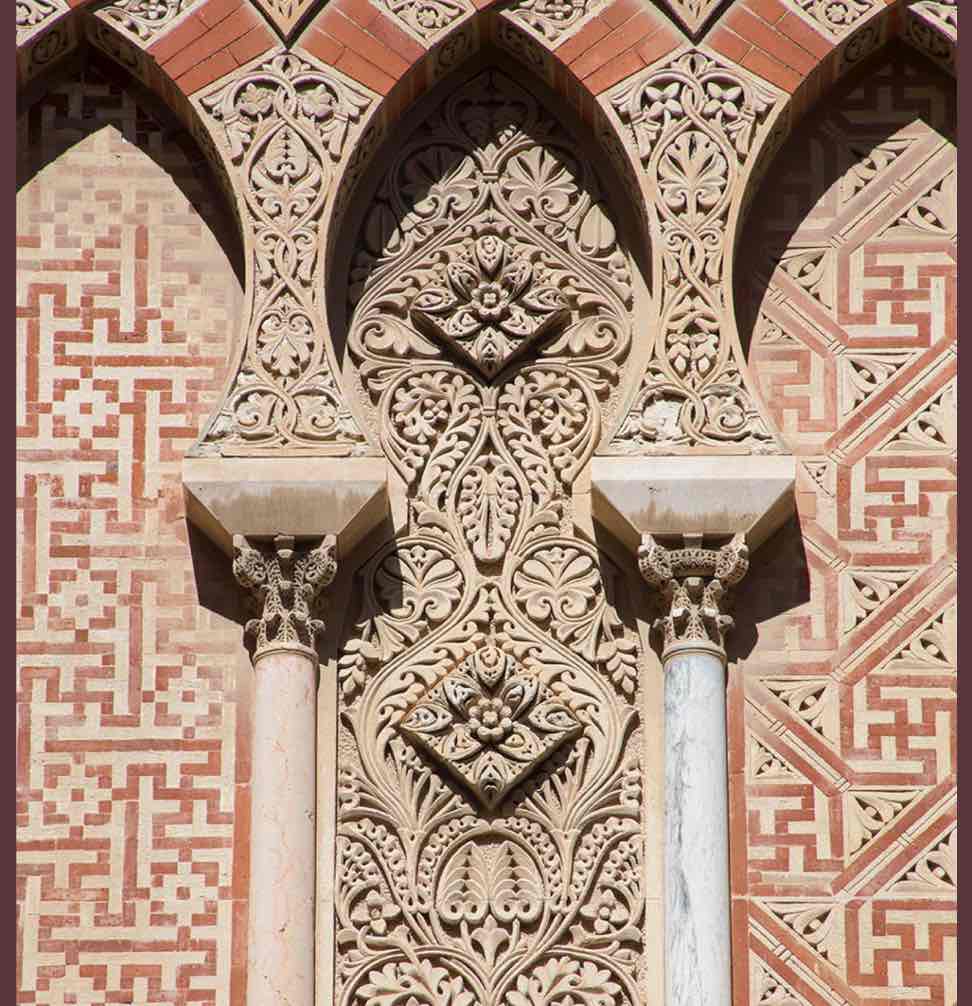

Detail from the exterior of the Great Mosque of Córdoba

Rebuilt during the Umayyad Dynasty (661-750 CE

Reflects the concept of impermanence, covering the monument with no direct connection to the interior. The relationship with nature, the abstraction of divine patterns through tessellation, and the idea of unity in ornamentation contribute to the broader theme of Islamic art as a reflection of creation and a unique perspective on the world.

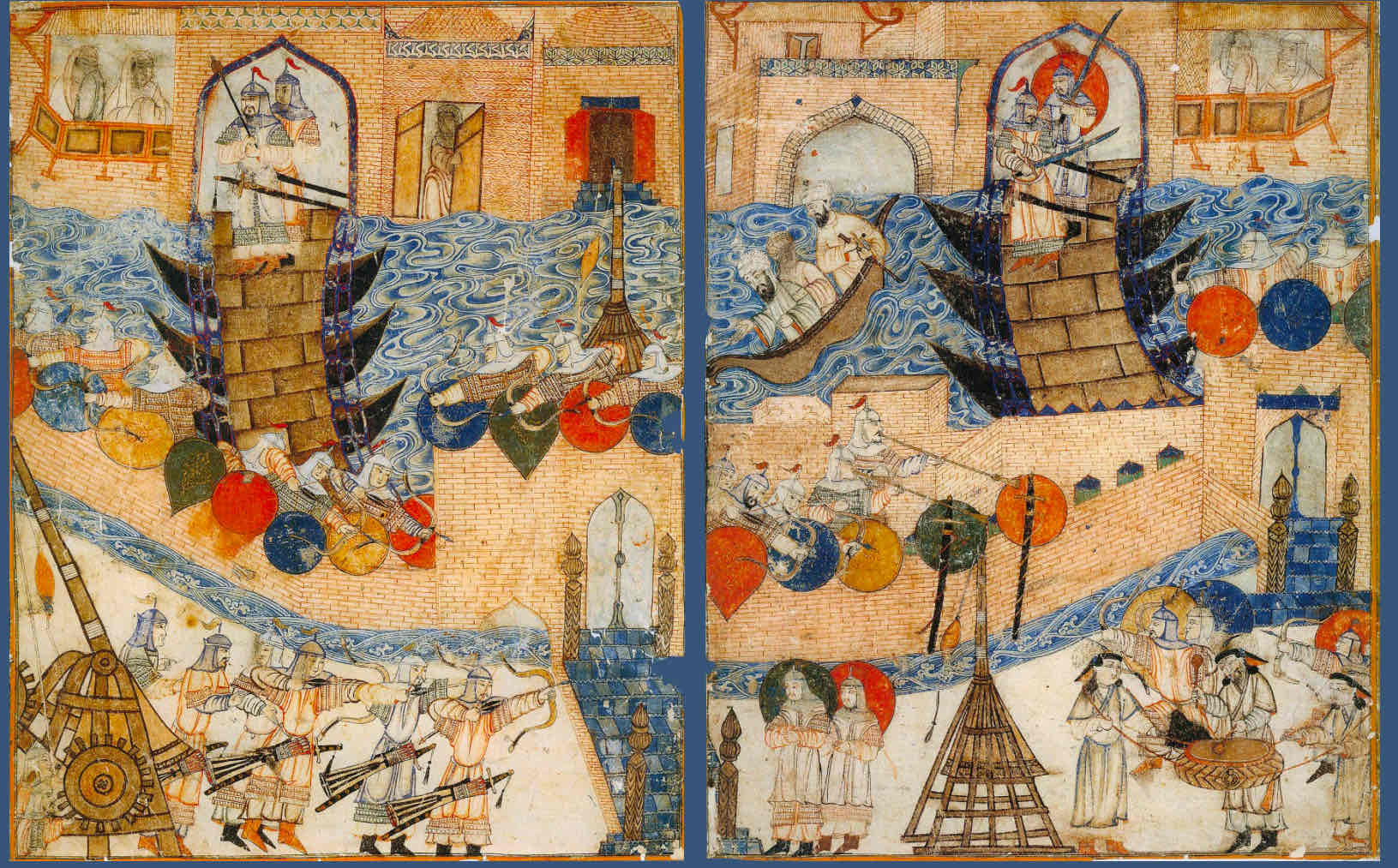

Double-page illustration of Rashid-ad-Din’s “Jāmi’ al-tawārīkh (Compendium of chronicles)”

Rashid-ad-Din

14th century CE

An example of paintings that do not follow western perspective, rather utilized a distorted sense of space to highlight multiple events in time. Viewers are free to enter and exit the piece at any point.

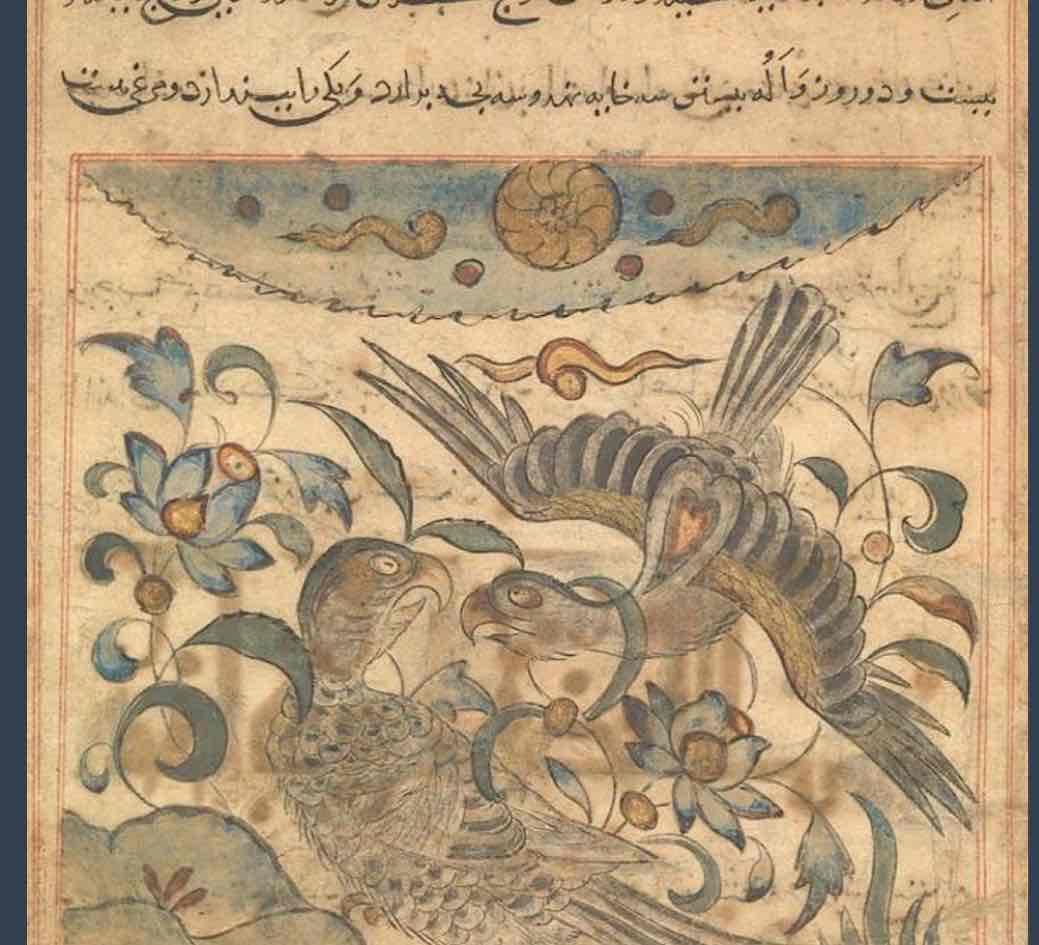

“Pair of Eagles” folio from Manafi’ al-Hayawan (On the Usefulness of Animals)

Ibn Bakhtishu

ca. 1300 CE

The folio illustrates the impact of Chinese art on the Iranian tradition, highlighting the cultural synthesis that occurred as a result of the Mongol conquest. This reflects the cross-cultural influences and exchanges during this period.

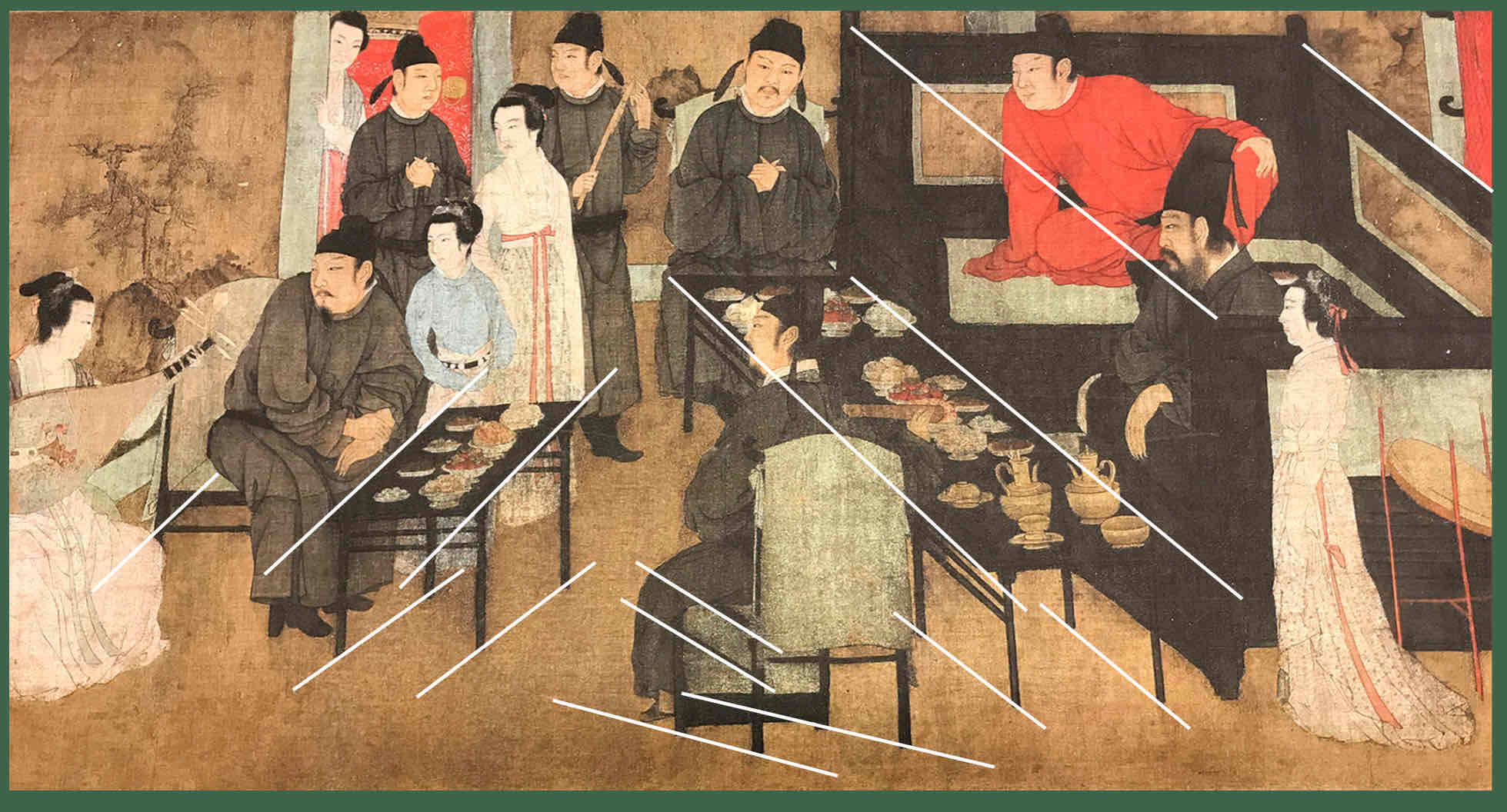

Night Revels of Han Xizai

Gu Hongzhong

937-975 CE

The emphasis on multiple vanishing points enhances the sense of interaction and movement within the painting. This aligns with the lecture's exploration of Persian painting introducing alternative spatial approaches that diverge from the linear perspective commonly found in European art.

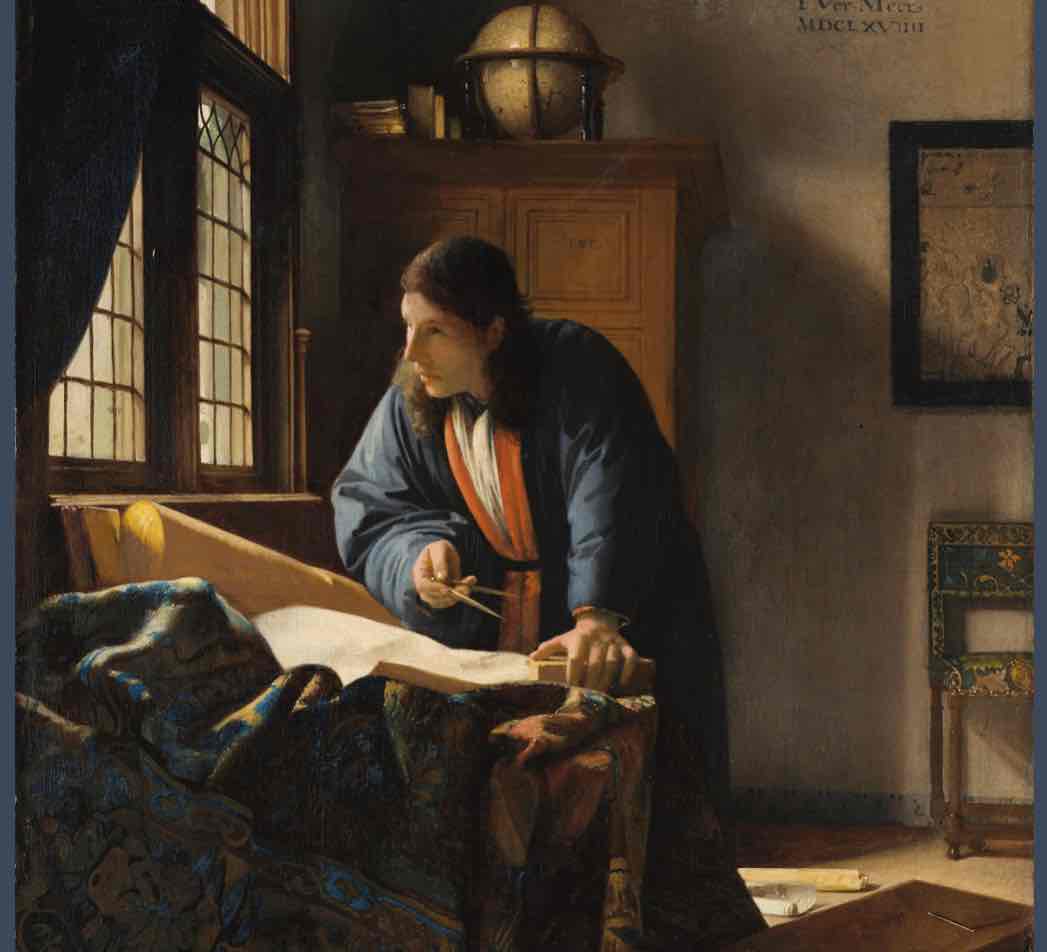

The Geographer

Johannes Vermeer

1668-69

Vermeer's composition, influenced by Renaissance perspective, is discussed in connection with Decartes' notion of a singular eye. This reflects the conflation of vision and truth in the Western tradition, reinforcing Western sentiments of superiority in comparison to “primitive” Eastern perspective

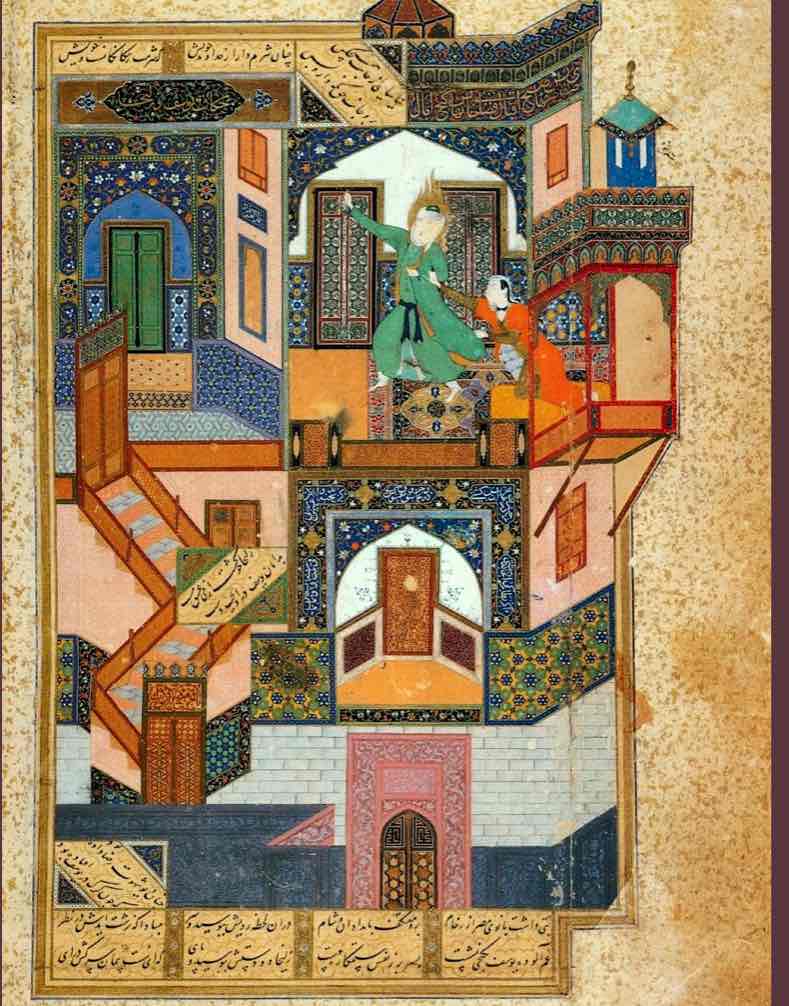

Yusuf and Zulaikha (Joseph pursued by Potiphar’s wife)

Kamal al-Din Bihzad

ca. 1488

In Islamic art, including Persian miniature painting, perspective is approached differently, often emphasizing intricate geometric designs, flattened space, and multiple viewpoints. This alternative spatial conception challenges the Eurocentric notion of perspective as the sole standard of artistic excellence, highlighting the diversity and sophistication of non-Western artistic traditions

Textile fragment with Nasrid Coat of Arms

ca. 1400

Represents the artistic legacy of the Arab Nasrid dynasty, which ruled over the Alhambra palace city in Granada, Spain during the 14th century. The intricate design and craftsmanship of the fragment, featuring the Nasrid Coat of Arms, exemplify the cross-cultural influences and the rich artistic heritage of Islamic, Jewish, and Christian traditions that flourished in the Iberian Peninsula during this period of Muslim caliphate rule.

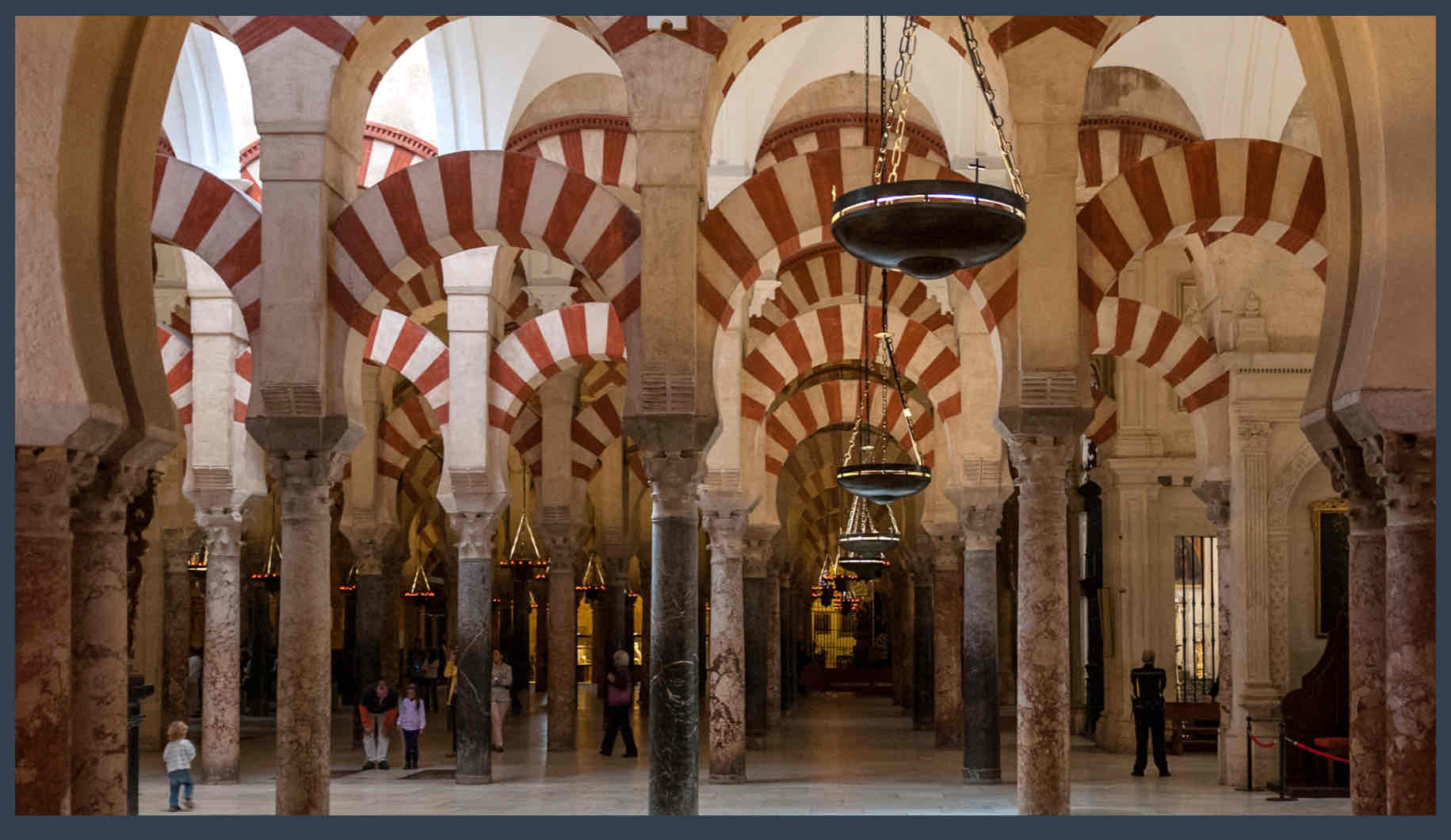

Hall of Prayer, The Great Mosque of Córdoba

784-786 CE

Reflects the deep cultural connections and cross-cultural interactions that characterized Islamic Spain during this period. Constructed by Muslims establishing a vibrant culture in Spain, the mosque exemplifies the fusion of Islamic architectural traditions with local influences, as well as serves as a communal space that holds memories and tributes to the Syrian homeland.

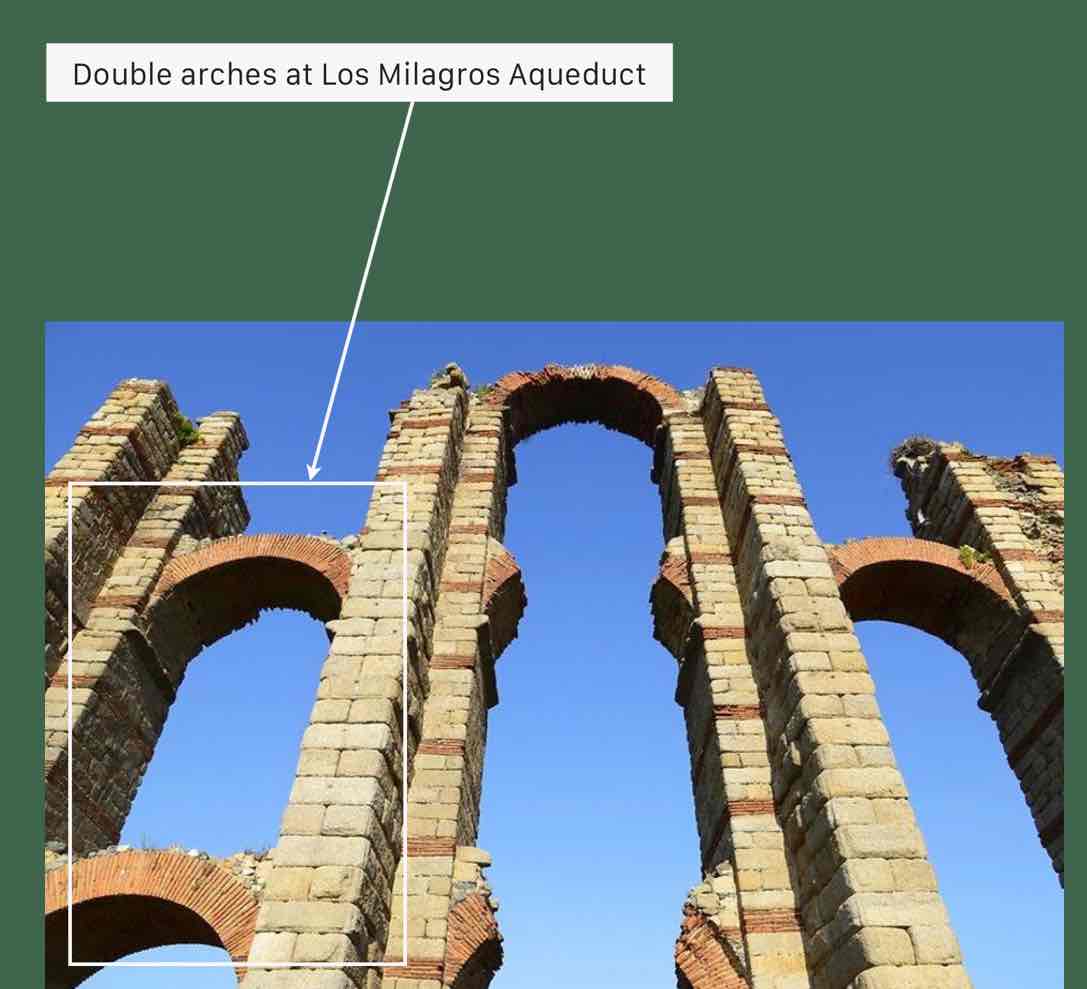

Los Milagros Aqueduct

100-300 CE

Over the centuries, this aqueduct has become not just a functional structure but also a symbol of wonder and admiration, earning the moniker “Aqueduct of the Miracles." The aqueduct's architectural complexity, characterized by its blend of orderly structure and visual chaos, reflects the dynamic interplay between tradition and innovation (such as Roman and Islamic architectual elements), embodying a dialogue between past and present civilizations.

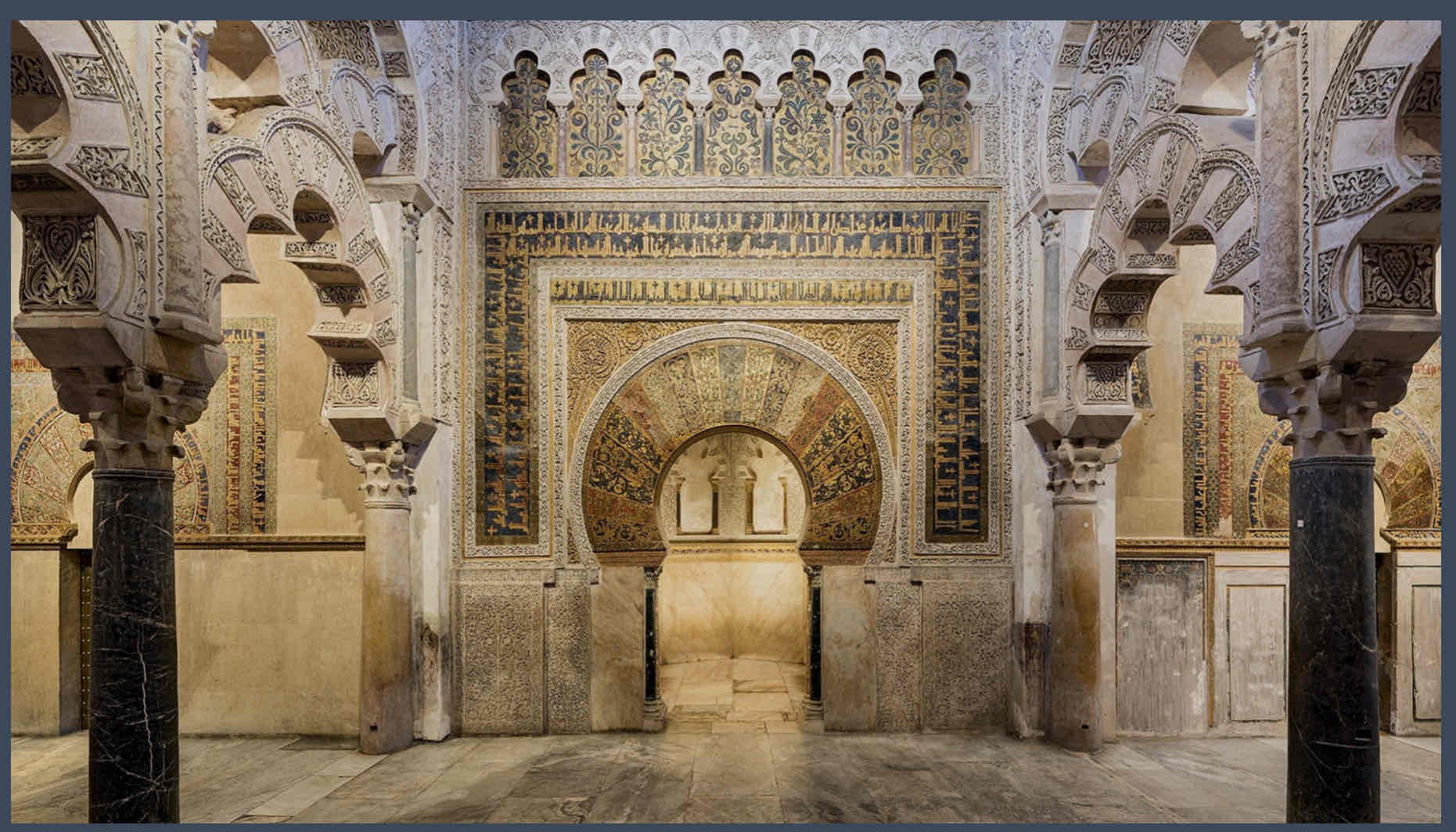

The Mihrab of the Great Mosque Córdoba

784-786 CE

Showcases the fusion of pre-existing regional traditions with innovative Islamic design elements. This architectural marvel not only facilitates the practical function of indicating the direction of Mecca for prayer but also symbolizes the Muslim world's ability to adapt and develop architectural styles based on local traditions.

Court of the Lions (Patio de los Leones)

The Alhambra Palace and Fortress

1362 CE

Emerges as a quintessential example of Islamic architecture during the Golden Age of Spain. As Muslims brought their architectural expertise and cultural influences from regions like Syria to Spain, they transformed the Mediterranean landscape, islamizing it and leaving an indelible mark on the architectural heritage of the Iberian Peninsula.

Femmes d’Alger dans leur appartement (Women of Algiers in their Apartment)

Eugène Delacroix

1834

Depicts a scene of four Algerian women in their lavishly decorated apartment, presenting them as exotic subjects for the European viewer's gaze. Delacroix's depiction of opium use and sexual connotations further underscores the Orientalist discourse that justifies colonial domination and exploitation.

Snake Charmer

Jean-Léon Gérôme

1879

Embodies the Orientalist perspective prevalent during the late 19th century, as evidenced by its portrayal of exoticism and cultural otherness. This painting aligns with themes of Orientalist logic in presenting the world as an exhibition, as depicted through the lens of European colonial dominance.

The ornamentations on the walls hint at the former glory of the East, now in a state of neglect and decay

Bonaparte Visiting the Plague Victims of Jaffa

Antoine-Jean Gros

1804

In this painting, Napoleon Bonaparte is portrayed as a divine figure, transcending the horrors of disease as he visits plague victims in Israel. Through such artistic representations, European powers perpetuated Orientalist narratives that justified their colonial dominance and portrayed the "other" as in need of their intervention and guidance.

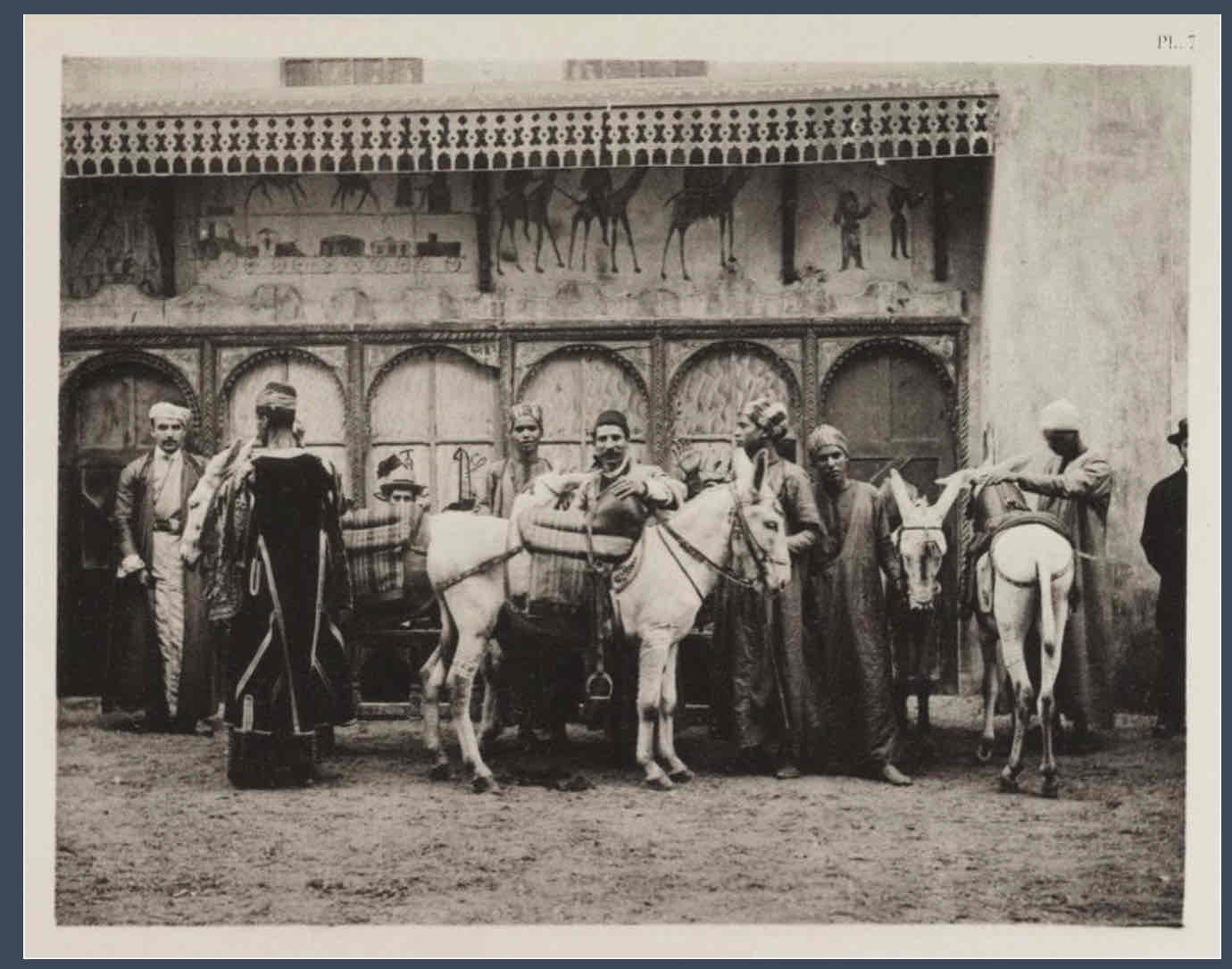

A group of Egyptians and imported donkeys from Cairo on the Rue du Caire at the Paris Exposition

1889

Reflects a romanticized view of Egyptian culture, characterized by Western fascination with the exotic and primitive. By importing donkey drivers and their animals from Cairo to Paris, Delort sought to immerse visitors in an imagined, Westernized version of Cairo, reinforcing stereotypes and perceptions of the Orient as lesser-than and otherworldly.

Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations

1851

These exhibitions aimed to showcase the cultures and achievements of various nations, but often portrayed the Middle East through staged scenes laden with Orientalist stereotypes. The Middle Eastern pavilions perpetuated Western supremacist notions, framing the region as and morally inferior to Western Christianity.

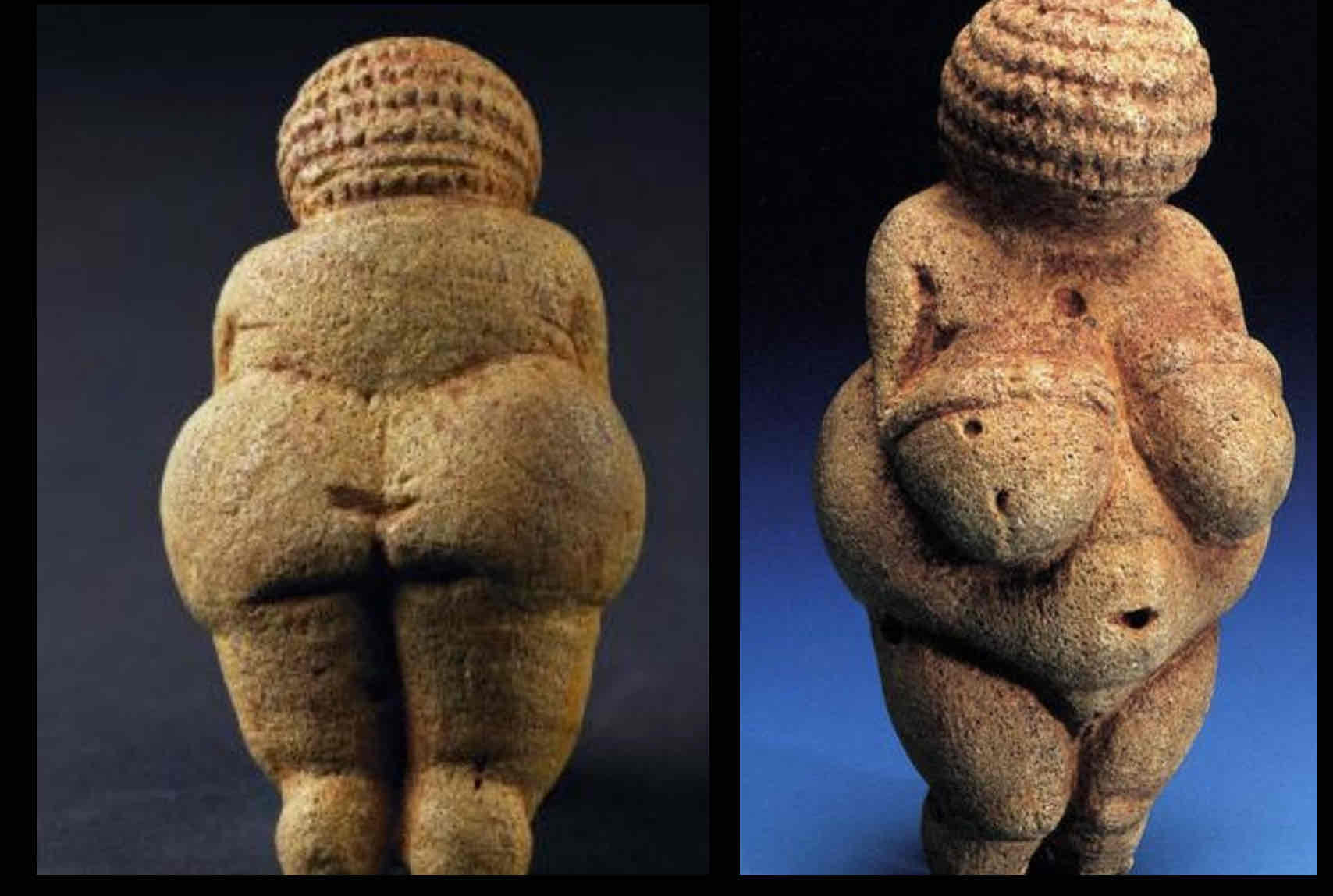

“Venus” of Willendorf

25-23.000 BP, discovered 1908

While traditionally interpreted as a fertility symbol due to its exaggerated features emphasizing aspects of fertility and maternity, such as large breasts and a rounded abdomen, recent scholarship suggests that this figurine also represents aspects of textile production. The reference to weaving techniques being used in its production indicates a connection between the Venus figurine and weaving culture among women

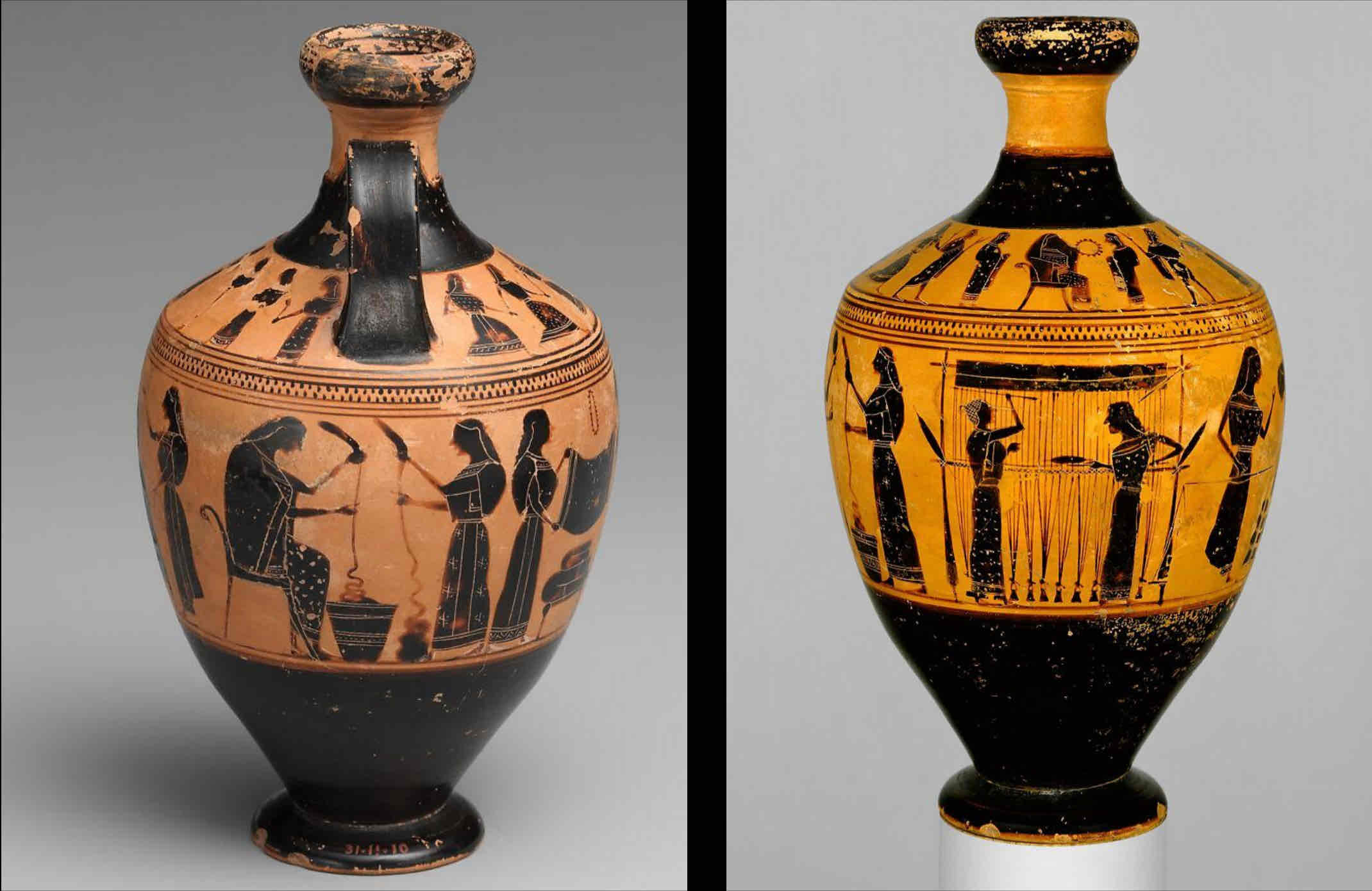

Terracotta lekythos (oil flask)

Amasis Painter, Greek

550-530 BCE

This ancient Greek artifact depicts scenes of women engaging in textile-related activities, such as preparing wool and weaving cloth. This aligns with the lecture's emphasis on the archaeological evidence globally indicating women's involvement in fiber processing, and weaving, highlighting their contributions to the economy while managing domestic responsibilities.

Women Preparing Newly Woven Silk

Song dynasty 12th century

Provides a representation of the involvement of women in textile production during ancient times. Depicting scenes of luxuriously adorned court ladies engaging in various stages of silk production, such as pounding silk, preparing thread, sewing, stretching, and ironing silk cloth, the artwork highlights the significance of women's roles in silk production rituals, known as gongcan or "palace sericulture"

Imperially Commissioned Pictures of Tilling and Weaving

Yuzhi gengzhi tu

Jiao Bingzhen

Kangxi Period, c. 17-18th century

Commissioned pictures like these played a significant role in documenting and commemorating the agricultural and weaving processes, showcasing the importance of these activities in Chinese society

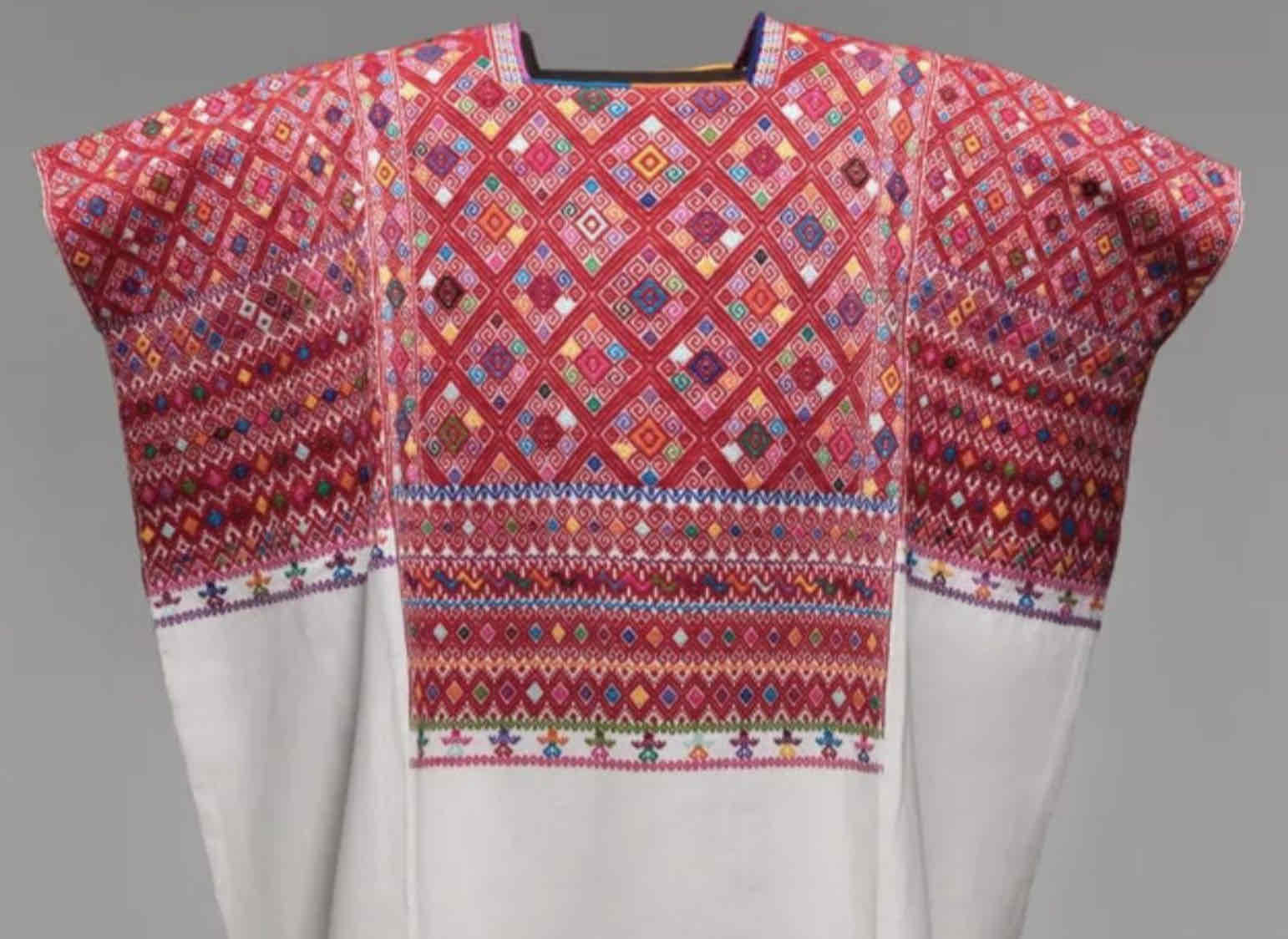

Ceremonial huipil (traditional blouse)

Maker unidentified

Symbolizes the ethnic identity of the Mayan people of Guatemala but also serves as a tribute to the vital role of women in preserving cultural heritage. Traditionally made with handwoven cloth on a backstrap loom by women, the huipil embodies centuries of skill and tradition passed down from generation to generation.

Tse’ Hone (Diné: Rock that Tells a Story aka Newspaper Rock

In the context of exploring the diverse functions of writing beyond recording spoken language, "Tse’ Hone" holds significance as a tangible example of writing serving as a medium for storytelling and cultural expression

Rock art petroglyphs / Shang bronze inscriptions

Exemplify the diverse functions of pictographic writing beyond mere recording of spoken language. These ancient forms of writing, spanning from the Shang dynasty to later periods, served as mediums for storytelling, religious rituals, and historical documentation.

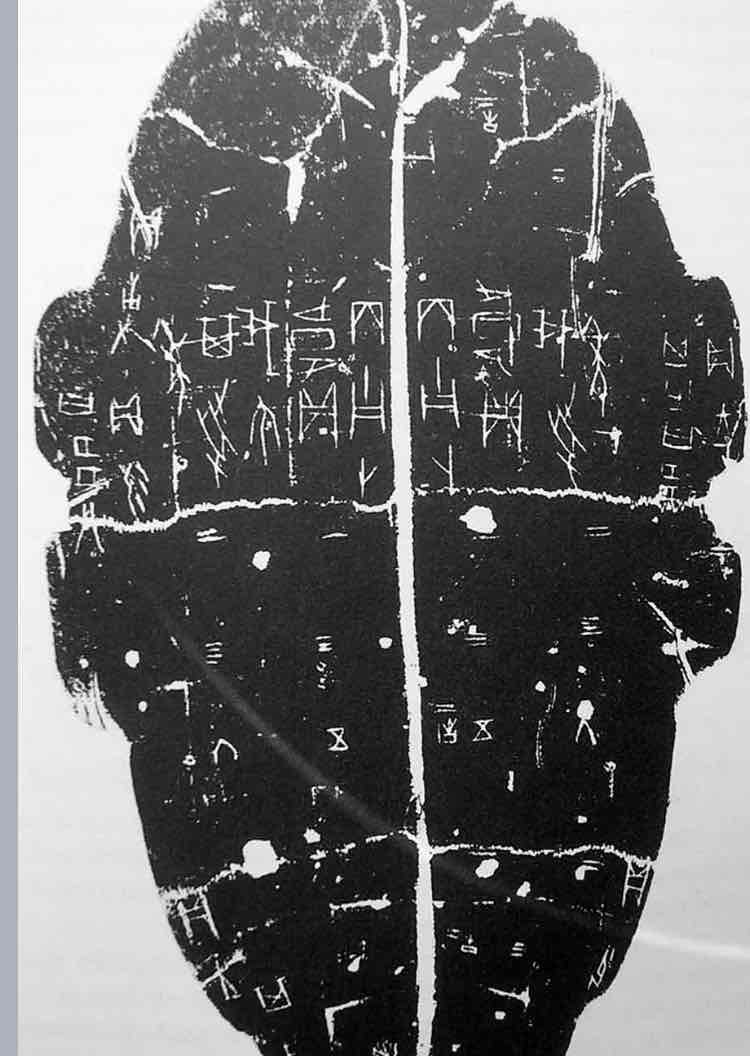

Shang oracle bone script

Dating back over 3000 years, these inscriptions served a dual purpose of divination and record-keeping for the Shang dynasty. Despite its ancient origins, oracle bone script laid the foundation for the evolution of Chinese writing systems, ultimately shaping the modern characters still in use today

Ai Weiwei “Crabs”

Both works epitomize the concept of symbolic communication through visual art. Much like "Shuang Xi," which symbolizes "double happiness" through visual imagery, "Crabs" communicates layers of meaning beyond literal script, demonstrating the diverse ways in which art serves as a medium for expression and cultural discourse.

Qiu zhijie Writing the “Orchid Pavilion Preface” One Thousand Times

Serves as an example of the intersection between calligraphy, repetition, and artistic expression. By meticulously copying Wang Xizhi's revered "Preface to the Poems composed at the Orchid Pavilion," Qiu underscores the idea that writing is not solely about conveying information but also about embodying a form of spiritual and artistic meditation.

Foiled plate with rocks, plants, and melons

Yuan dynasty (1271-1368), 14th century

Reflects the evolving aesthetics of Chinese porcelain influenced by foreign trade, particularly with Persia, during the Song dynasty. This piece showcases the integration of Islamic-inspired blue and white underglaze designs, highlighting the cultural exchange and interaction between China and Persia. It symbolizes the dynamic nature of identity and artistic expression, emphasizing the fluidity of cultural influences over time.

Koryo (Goryeo) celadon maebyong with incised dragons

c. 12th century

Celadon ceramics showcase the mastery of Korean potters who adapted and refined techniques borrowed from China. This piece underscores the cultural exchange and innovation that characterized East Asian ceramic production, highlighting Korea's significant contribution to the development of celadon ware.

Fission Time

Li Xiaofeng

2018

Encapsulates the intersection of Chinese heritage and global influences. Using porcelain from the Ming and Qing dynasties, Li reimagines the traditional qipao dress, popularized in the 1930s-40s by Western culture, to explore themes of globalization, cultural hybridity, and the circulation of materials.

Still Life with Moor and Porcelain Vessels

Jurriaen van Streek

c. 1670

Captures the allure of blue and white porcelain, a prized symbol of wealth in western culture. Through the portrayal of exotic figures alongside prized porcelain vessels, the artwork prompts viewers to contemplate themes of wealth, status, and identity intertwined with global trade and exchange during the 17th century.

Chini-khana (porcelain house)

1607-1611

Showcases the cultural significance of porcelain in Persian art and architecture. Underscores the influence of porcelain on various cultures beyond its country of origin, illustrating its widespread appeal and symbolic value across different regions.

Artificial Rock

Zhan Wang

2001

Replication of the DongTien rock forms found in Chinese Gardens as important centerpieces shaping gardens (refer to Mysterious Heavens reading). These structures were admired similarly to how calligraphy was a free-flowing art form. The sense of dynamic form, energy, and occurring rocks in various materials, including jade, glass, and ceramics, is made of steel, challenging us to redefine the parameters of tradition and the modern, contemporary world.

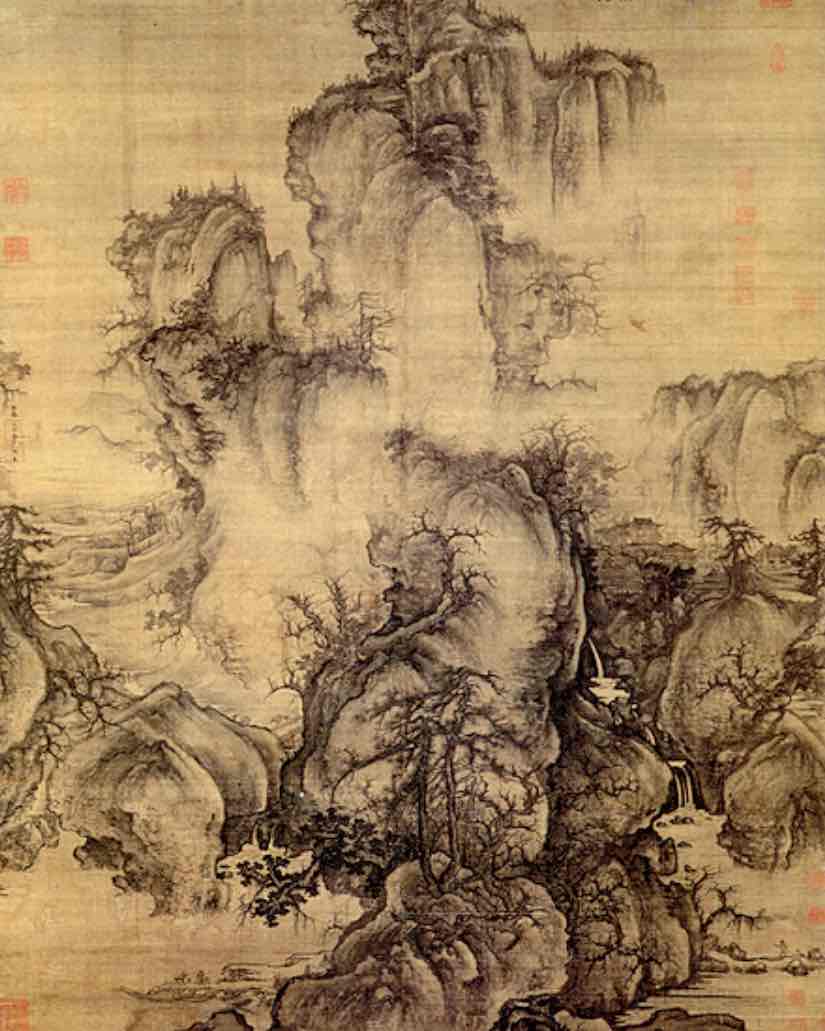

Early Spring

Guo Xi

1072

Embodies the quasi-religious reverence for nature prevalent in Chinese culture, suggesting that nature surpasses humanity in importance. Guo Xi's masterpiece invites viewers to immerse themselves in the tranquil beauty of the landscape, offering a sense of renewal and connection to the natural cycles of life amidst urbanization.

Huijing Pond

Huijing Pond in Yuyuan Garden, Shanghai, epitomizes the profound significance of Chinese garden design within the broader context of landscape aesthetics. As a central feature of the garden, Huijing Hall symbolizes joy and glory, serving as a space for contemplation and appreciation of the surrounding waterscape.

Jade stone peak Yulinglong

Serves as a captivating testament to the profound reverence for nature and harmony within Chinese garden design. Despite its considerable weight, the rock's presence epitomizes a deep bond with the earth, evoking ancient spiritual connections to natural elements and the celestial realm. Through its strategic placement and symbolic significance, the Jade Stone Peak embodies the interplay of darkness and light, yin and yang, echoing themes of balance and harmony inherent in Chinese landscape aesthetics.

Dragon Wall

Encapsulates the essence of Chinese landscape aesthetics, where nature intertwines seamlessly with cultural symbolism. As integral components of the garden's design, the Dragon Walls not only demarcate different areas but also serve as conduits for the flow of energy, imperial power, and storytelling, enriching the visitor's experience with layers of meaning drawn from both nature and mythology.

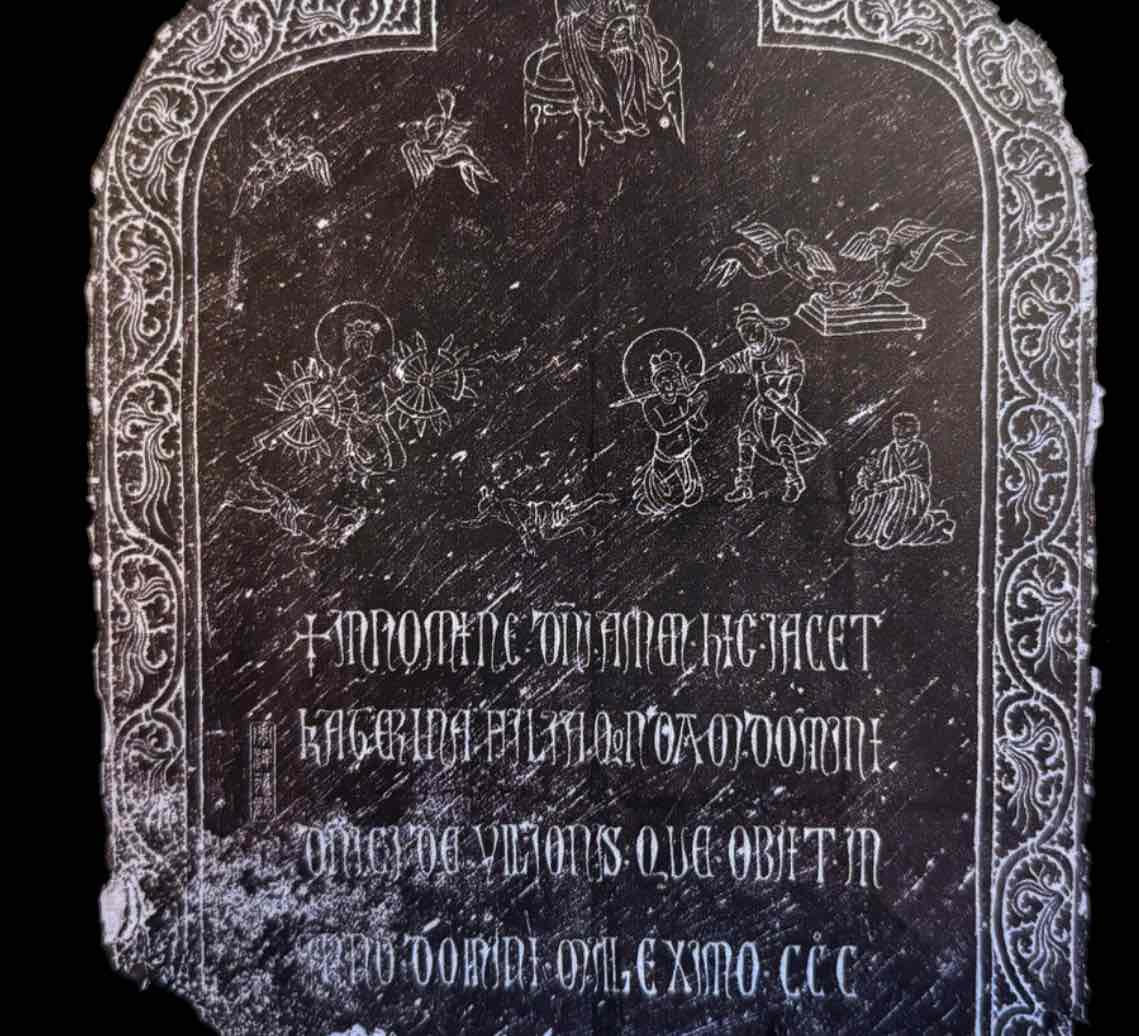

Tombstone of Katerina Vilioni

June 1342

As the gravesite of an Italian woman connected to China through the Silk Road, this tombstone's iconography is noteworthy as it blends Chinese aesthetic elements with European Christian imagery. Through the medium of the tombstone, scholars can unravel the complexities of medieval identity, challenge Eurocentric narratives of the Middle Ages, and appreciate the interconnectedness of global cultures during this era of history.

Lewis Chess Pieces

Late 12th - 13th century

Reflects the interconnectedness of medieval societies. These British chess pieces, discovered in Scotland, highlights the global reach of medieval trade and cultural exchange, as they were likely made from materials obtained through Viking encounters with Indigenous Inuit peoples, particularly from Greenland.

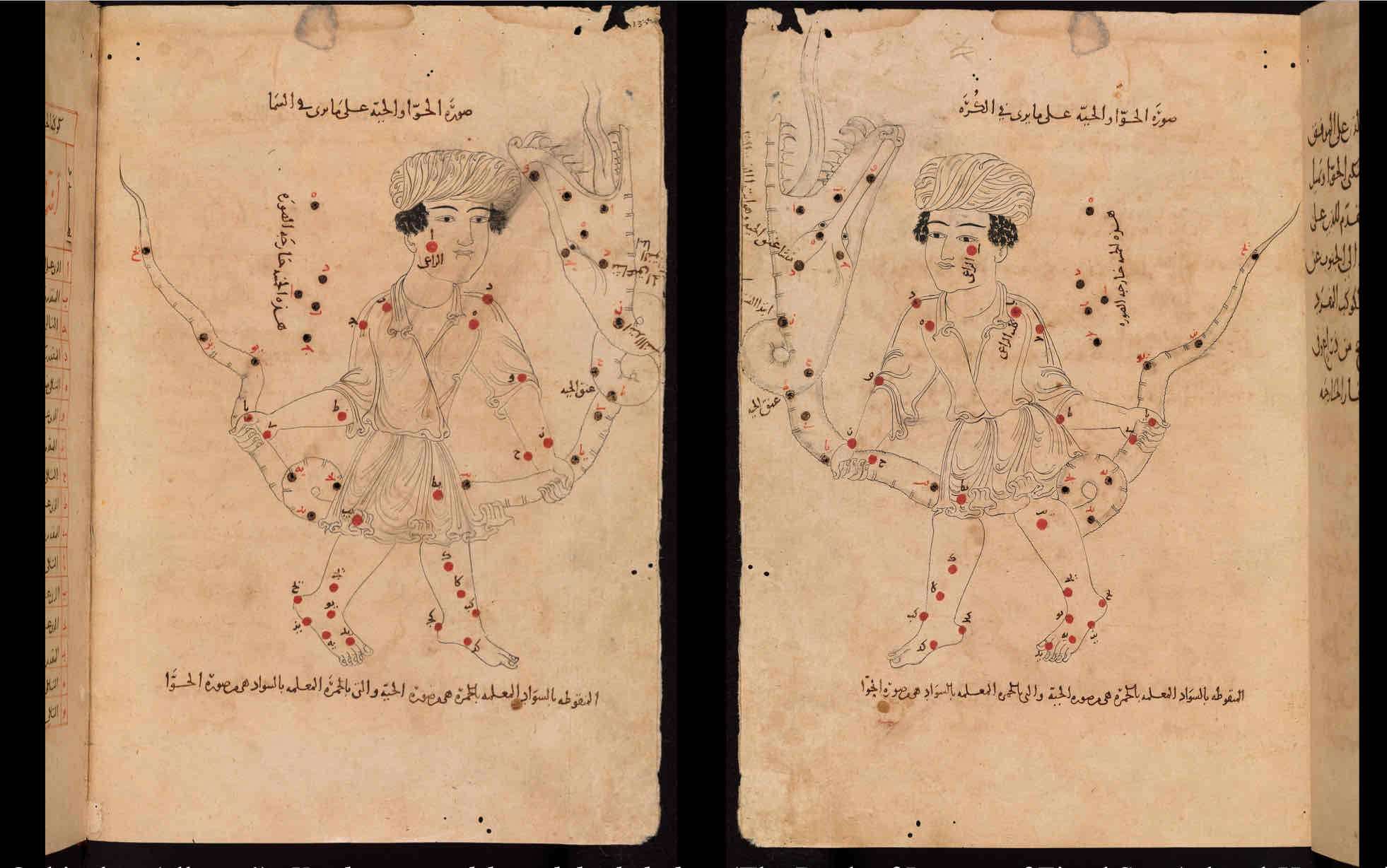

The Book of Images of Fixed Stars

al-Husayn ibn ‘Abd ar-Rahmān al-Sūfī

1009

Underscores the cultural subjectivity inherent in interpreting celestial phenomena. Through works like this, scholars can appreciate the multiplicity of perspectives and the richness of knowledge across different cultural contexts during the medieval period. The book serves as a practical tool for celestial navigation and timekeeping, reflecting the Islamic world's advanced understanding of astronomy and its integration into daily life.

The Star Mantel of Emperor Henry II

Makers once known

1018

The embroidered inscriptions reflect cultural influences from the Byzantine Empire and Ottonian manuscript illuminations, illustrating the adaptation and reinterpretation of artistic styles across regions. Through artifacts like the Star Mantel, scholars can appreciate the intricate layers of cultural exchange and the rich tapestry of medieval societies.

“The Zodiac Man”

Pol de Limbourg

1409

The figure's body is associated with different astrological signs, reflecting the belief in the interconnectedness between celestial bodies and human health. Through artworks like "The Zodiac Man," scholars can observe how cultural contexts shape the interpretation and application of astronomical knowledge, highlighting the diversity of experiences with astrology across different societies.

Reliquary Purse of Saint Stephan

Artist(s) once known

ca. 815-830 CE

Exemplifies the significance of reliquaries in transforming ordinary objects into vessels of profound meaning. Despite its subtle narrative elements, such as a discreet cross symbolizing Saint Stephen's martyrdom by stoning, its elaborate design elevates the purported relics within, granting them validation and spiritual significance.

Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, view of the nave elevation

Architects and engineers once known

1075-1122 CE

Acts as a monumental symbol of pilgrimage in Christianity, particularly to the relic of Saint James. The cathedral's role in fostering pilgrimage routes, such as the Camino de Santiago, underscores its enduring significance as a cultural and historical landmark, embodying the intersection of religious devotion, architecture, and human experience.

The reliquary of St. Foy

c. 1000 CE with later additions

The reliquary’s deliberate use of "spoila" from Roman statues, including the head, enhances St. Foy's relic's authenticity and prestige, reflecting the medieval reverence for Roman art and contributing to the relic's cultural significance.

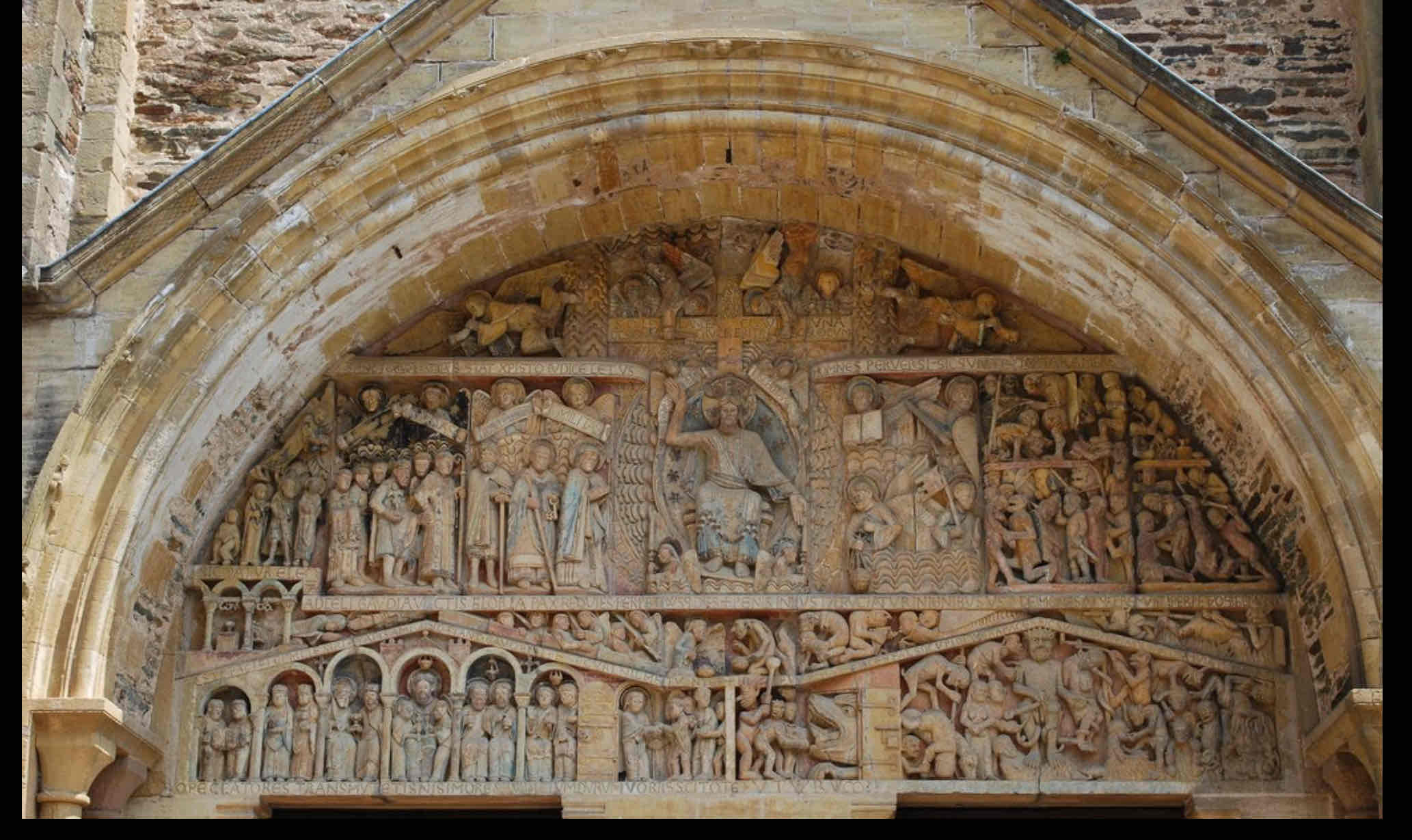

Last Judgement Tympanum

Artist(s) once known

c. 1130 CE

Adorning the entrance of the church, it serves as a powerful visual representation of the final judgment, warning pilgrims of the consequences of sin. This intricate artwork, often translated by monks to pilgrims, sets the tone for their spiritual journey and underscores the importance of redemption and piety in medieval Christian pilgrimage.

Pilgrim’s Badge for the Shrine of St. Thomas Becket

1320-1375 CE

Holds significance as a tangible symbol of pilgrimage devotion. Crafted from tin, these badges were popular souvenirs for pilgrims visiting the shrine of St. Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral. They served as personal mementos and outward signs of the pilgrims' spiritual journey, reflecting the widespread practice of pilgrimage in medieval Europe and the veneration of saintly relics.

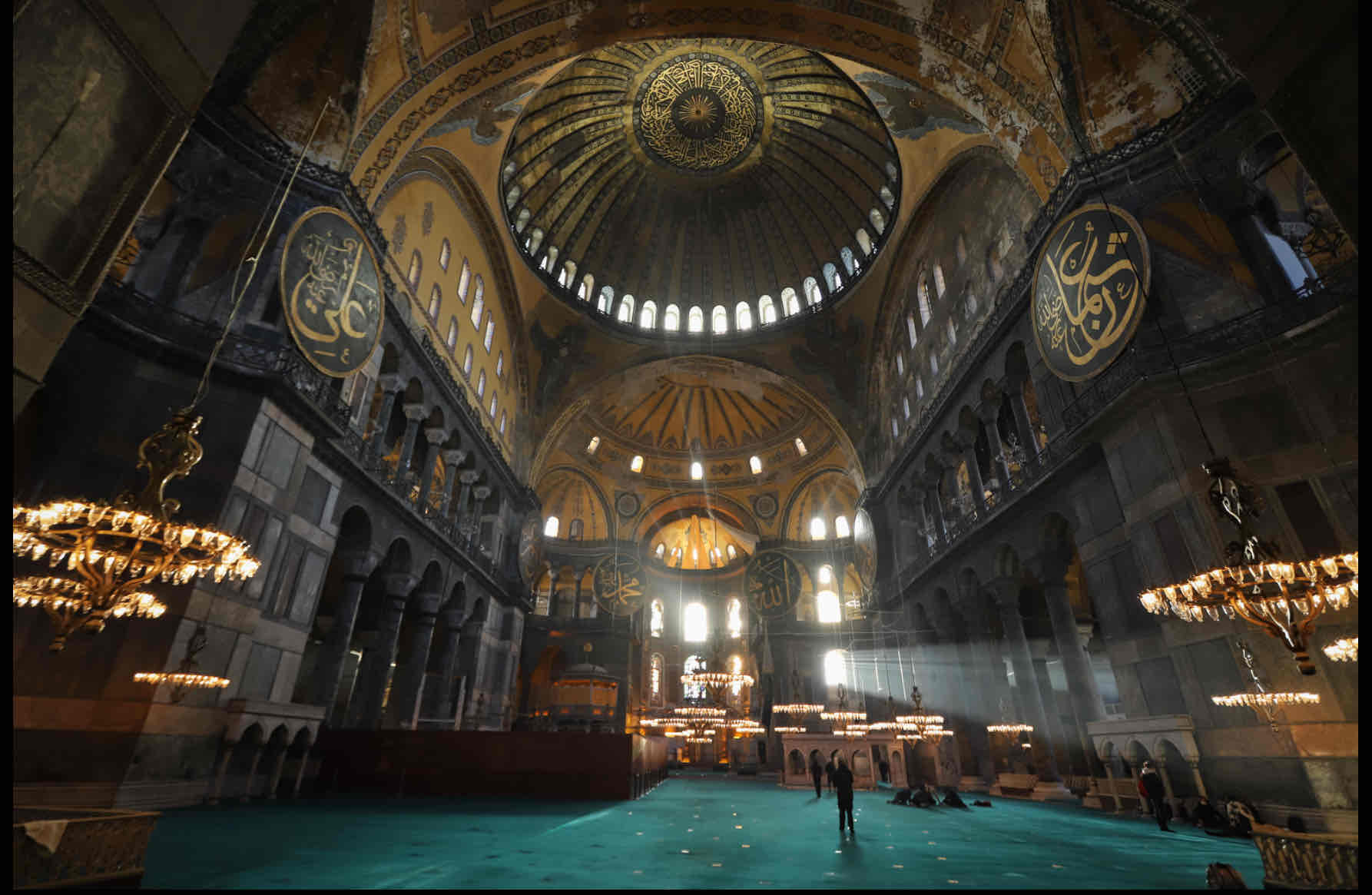

Hagia Sophia Cathedral

Anthemois of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus

532-37 CE

Its innovative features, including the massive dome supported by pendentives and a sophisticated structural support system, represent a pioneering engineering achievement. The cathedral's strategic use of light, facilitated by expansive windows and openings, creates a transcendent atmosphere, elevating the spiritual experience of visitors. As a "total work of art," every aspect of its construction contributes to its enduring significance as an architectural masterpiece in religious reverence.

East end, Basilica Cathedral of St. Denis

Architects and engineers once known

Planned with Abbot Suger

1140-44

Marks a significant development in Gothic architecture. The introduction of groin arches allowed for more open spaces and increased natural light, a departure from the Romanesque style. This reflects the lecture's exploration of how medieval cathedrals evolved to engage the senses and emotions of the beholder. Additionally, the use of groin arches, which had earlier roots in Islamic architecture, suggests cultural exchange and communication between different civilizations, echoing the lecture's theme of architectural influences transcending geographical and cultural boundaries.

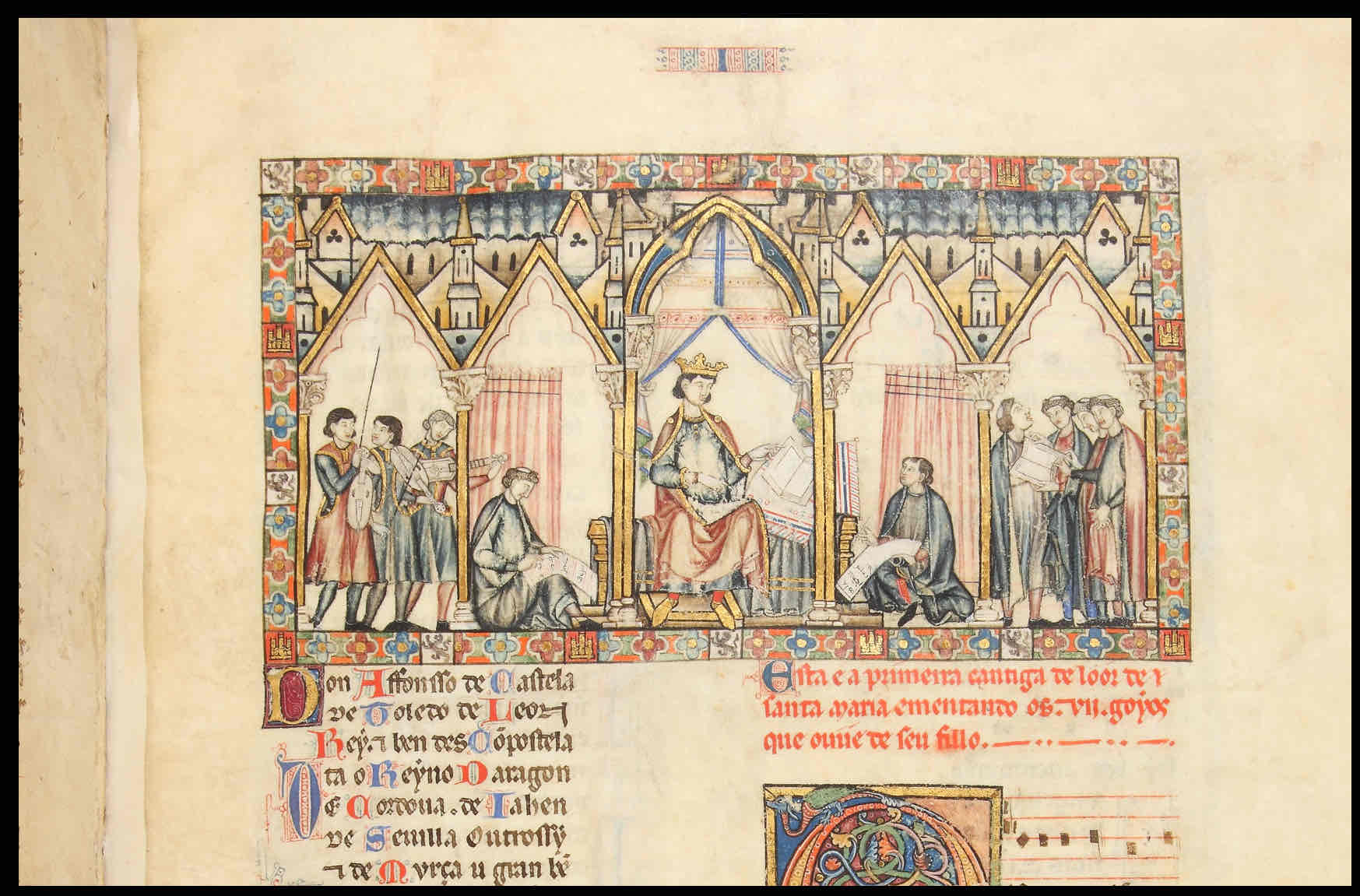

Cantigas de Santa Maria (Songs of Holy Mary)

Painter once known

Written by and for Alfonso X of Castile, Spain

1221-1224 CE

The popularity of this chant exemplifies the integration of music and spirituality in medieval cathedral culture. These songs, accompanied by vibrant illustrations, were intended for worship, meditation, and expressing devotion to the Virgin Mary. The emphasis on music in cathedrals aligns with the lecture's exploration of architecture as a multisensory experience, where sound contributes to the spiritual ambiance.

Censer

Maker once known

13th century

Incense, often used during religious ceremonies, rituals, and processions, played a significant role in enhancing the sensory atmosphere within cathedral spaces. The use of censers, like this one, highlights the integration of ritual objects into the architectural and spiritual fabric of medieval religious practice, emphasizing the holistic approach to worship and devotion.

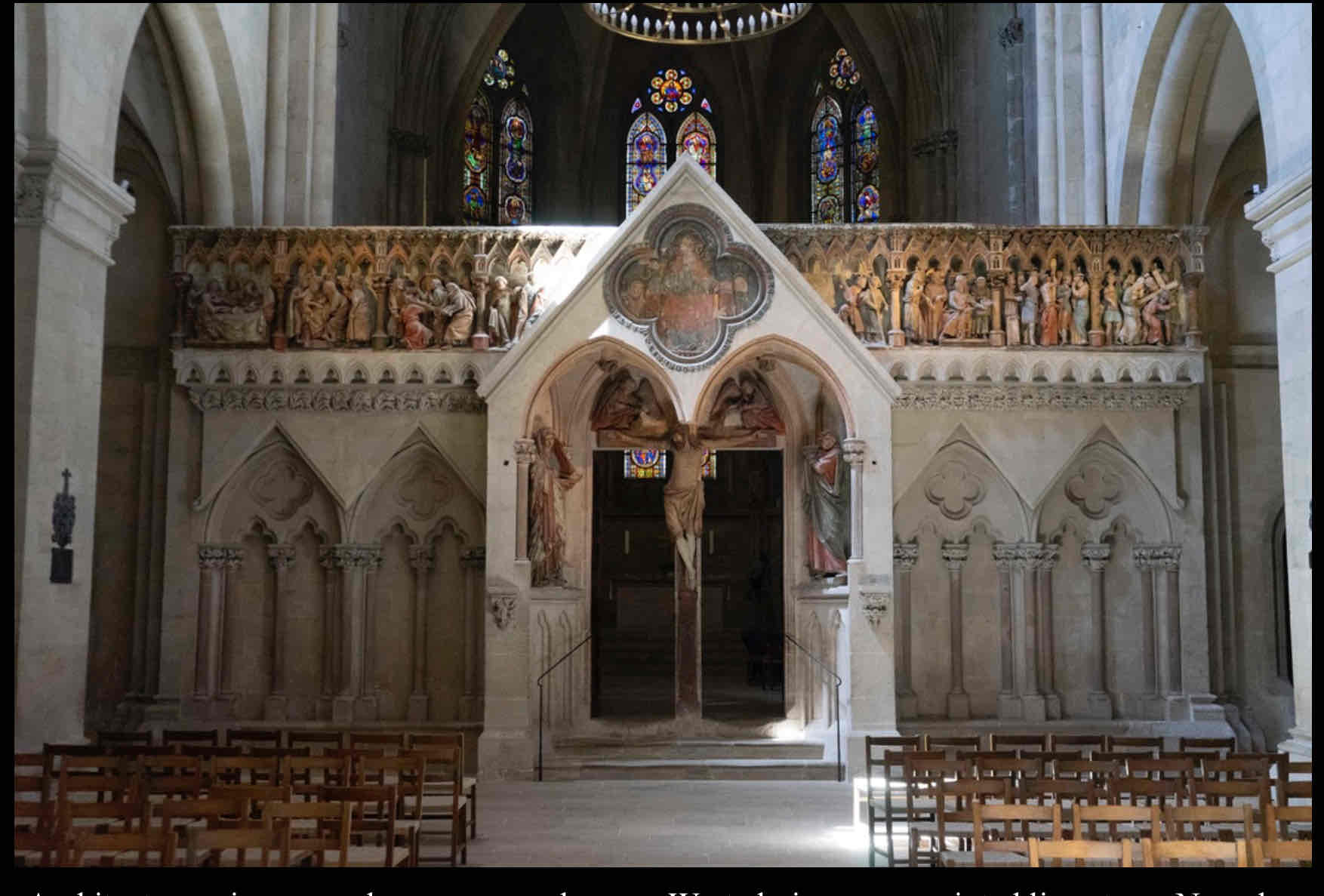

West choir screen in Naumburg Cathedral

Artists once known

1250 CE

Serves as a physical and emotional threshold within the sacred space. Adorned with expressive statues of Jesus, Mary, and John, the screen adds an aura of mystery and solemnity to the cathedral interior. As visitors approach, they are compelled to pause and contemplate their presence in relation to the divine, embodied by the statues, fostering a heightened sense of spiritual awareness and connection.