Study Guide 4

1/64

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

65 Terms

Scene size-up

the steps taken when approaching the scene of an emergency call: checking scene safety, taking standard precautions, noting the mechanism of injury or nature of the patient’s illness, determining the number of patients, and deciding what, if any, additional resources to call for.

SAMPLE - Patient History

Signs & Symptoms

Allergies

Medications

Pertinent Past Medical History (past/present)

Last Oral Intake (including meds)

Events Leading Up to the Present Illness

OPQRST - Pain Assessment

Onset - When did the pain start? Did it begin suddenly or gradually? Was the patient at rest or active?

Provocation / Palliation - What makes the pain better or worse? Does any position or movement affect it?

Quality - How does the pain feel? Is it sharp, dull, throbbing, etc?

Region / Radiating - Where is the pain located? Does it spread?

Severity - How severe is the pain on a scale from 0 to 10, with 10 being the worst pain imaginable?

Time - When did the pain start, and how has it changed over time?

ENAMES - Scene Survey / Scene Size-up

Environment

Number of Patients

Additional Resources Needed

Mechanism of Injury (or nature of illness)

Evacuation / Extrication

Spinal Precautions Indicated?

Signs & Symptoms

Identify the main issue the patient is experiencing. This helps in understanding the current illness or injury.

Allergies

Note any allergies, especially if they relate to medications or food, as these can impact treatment options.

Medications

Record all medications the patient is taking, including prescription, over-the-counter, and supplements. This can provide insights into existing medical conditions.

Pertinent Past Medical History

Gather information on any past medical issues that might relate to the current condition. This includes previous surgeries or chronic conditions.

Last oral intake

Determine when and what the patient last ate or drink, as this can affect symptoms and treatment, especially if surgery is needed.

Events Leading to the Present Emergency

Understanding the sequence of events that led to the current situation, which can help in diagnosing and treating the patient.

PASTE - shortness of breath

Progression - Questions about when the symptoms started and if they've gotten worse. “When did the pain start? Did it begin suddenly or gradually?”

Associated Chest Pain - Is there any chest pain accompanying the breathing difficulty?

Sputum Production - Is there any sputum (coughed-up material)? If so, what color and amount?

Talking tiredness - How easily can the patient speak? Are they able to complete full sentences?

Exercerise Tolerance - How does physical activity affect their symptoms?

JVD - Jugular Vein Distension

Bulging of the neck veins; may indicate heart failure or other obstructive conditions within the chest.

Causes: tension pneumothorax, cardiac tamponade

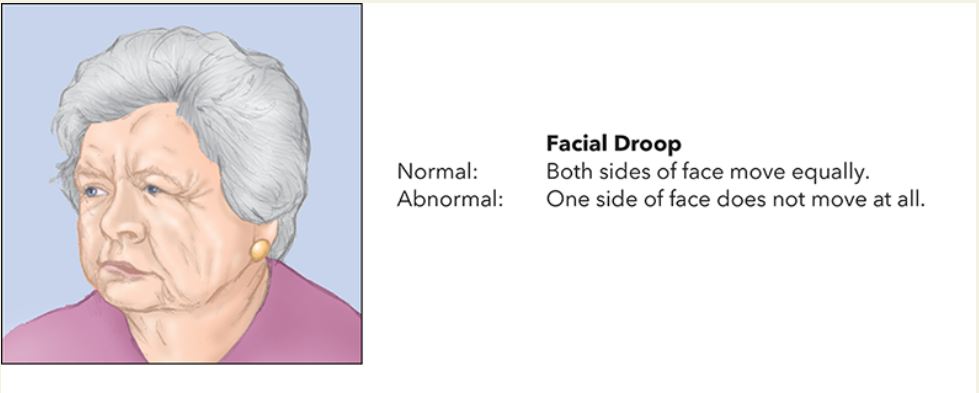

Cincinnati Stroke Test (FAST)

A quick and effective method to assess potential stroke symptoms in conscious patients.

Facial Droop

Ask the patient to grimace or smile. (Demonstrate what you want the patient to do, making sure that you show your teeth. This allows you to test the control of the facial muscles.)

A normal response is for the patients to move both sides of their face equally and to show you their teeth.

An abnormal response is unequal movement or no movement at all.

Dyspnea

Shortness of breath; labored or difficult breathing.

Work of Breathing

Refers to the effort required to inhale and exhale.

Nasal Flaring:

The nostrils widen with each breath, a sign that the person is trying to take in more air.

Chest Retractions:

The skin on the chest pulls inward between the ribs, above the breastbone, or below the ribcage as the person inhales.

Body Positioning:

Leaning forward or using accessory muscles to breathe can help the individual take deeper breaths.

Sacral Edema

Refers to the swelling that occurs in the sacral area, particularly in bedridden patients. This condition is often associated with heart failure, where fluid accumulates due to the heart’s inability to pump blood effectively.

Typically a result of right-sided heart failure.

Differential Diagnosis

A systematic method used by healthcare professionals to identify a disease or condition in a patient. It involves creating a list of possible conditions that could cause the patient’s symptoms and then narrowing down the list through further evaluation and testing.

Orthopnea

a condition characterized by difficulty breathing when lying down, which improves when sitting or standing upright.

It is a common symptom of underlying heart or lung conditions, such as heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which cause fluid to build up in the lungs when in a supine position.

Head-On Collisions

Up-and-Over Pattern:

Patient follows a pathway up and over the steering wheel, commonly striking the head on the windshield (especially when not wearing a seat belt), causing head and neck injuries.

In addition, the patient may strike the chest and abdomen on the steering wheel, causing chest injuries or breathing problems and internal organ injuries

Down-and-Under Pattern:

The patient’s body follows a pathway down and under the steering wheel, typically striking the knees on the dash, causing knee, leg, and hip injuries.

Rear-End Collisions

Typically cause whiplash, with the head jerking backward and forward, leading to neck, head, and chest injuries.

Side-Impact Collisions (T-bone)

The body is pushed laterally, causing injuries to the neck; head, chest, abdomen, pelvis, and thighs may be struck directly (causing skeletal and internal injuries.)

Rollover Collisions

Most serious, because of the potential for multiple impacts; frequently cause ejection of anyone who is not wearing a seat belt. Expect any type of serious injury pattern.

Rotational Impact Collisions

Involve spinning after an initial impact, causing multiple injury patterns.

Motorcycle and ATV Accidents

These vehicles offer little protection, leading to severe injuries, especially if the rider is ejected.

Vital Signs

Pulse, respiration, blood pressure, and skin color; pupils and pulse oximeter are not apart of vital signs.

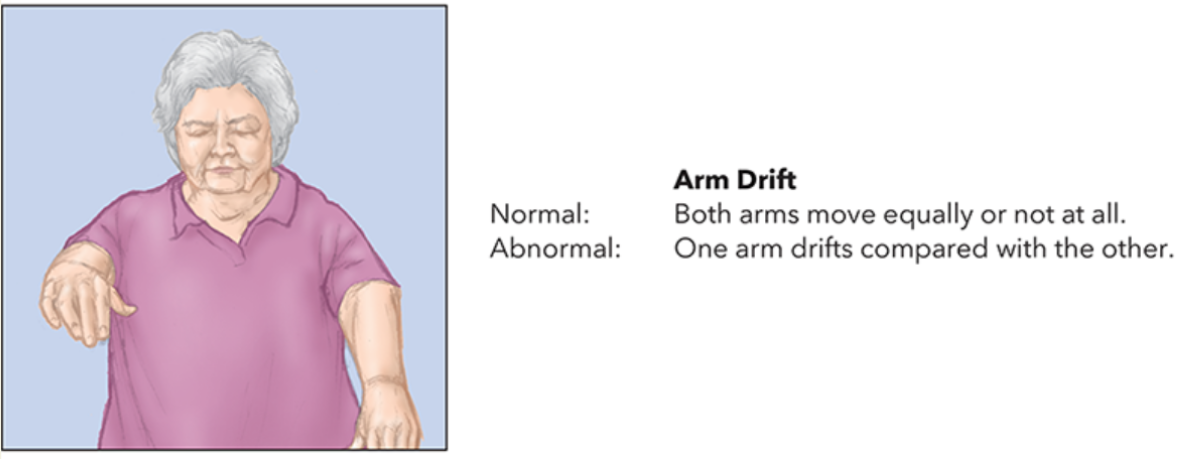

Arm Drift

Ask the patient to close their eyes and extend their arms straight forward with the palms facing upward. Have this patient hold this position for 10 seconds.

A normal response is for the patient to move both arms at the same time.

An abnormal response is for one arm to drift down or not move at all, or for the arms to turn downward so that the palms face the opposite direction.

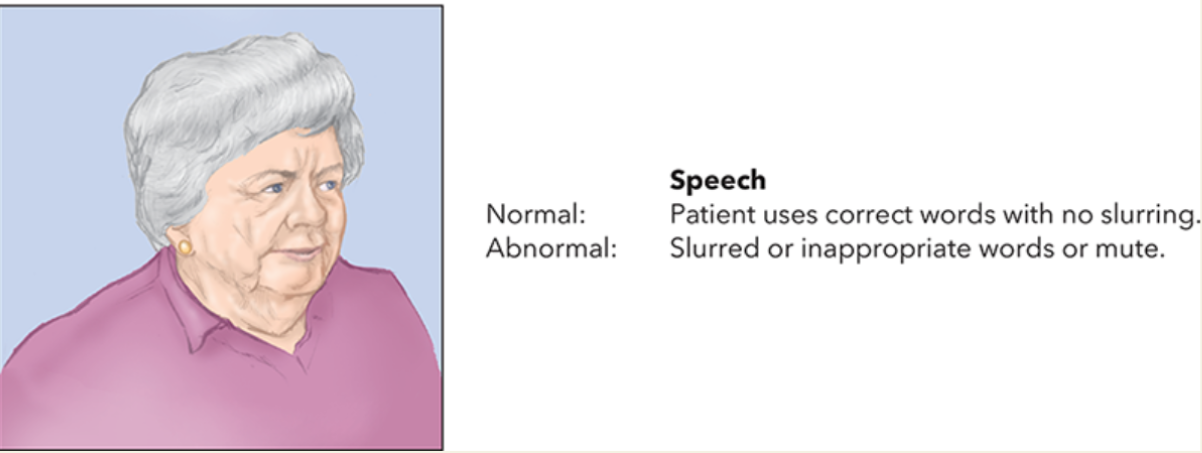

Speech

Ask the patient to say, “You can’t teach an old dog new tricks.” An uninjured person’s speech is usually clear.

A stroke patient is more likely to show an abnormal response to the test, such as slurred speech, the wrong words, or no speech at all.

Normal Ranges and Shock Presentation For Adults

Normal Ranges:

Pulse: Adults typically have a pulse rate of 60-100 beats per minute.

Respirations: Normal respiratory rate for adults is 12-20 breaths per minute.

Blood Pressure: A normal blood pressure is reading around 120/80 mmHg.

Patient Presentation in Shock:

Altered Mental Status: Anxiety, restlessness, or combativeness due to low oxygen to the brain.

Skin: Pale, cool, and clammy as blood is diverted to vital organs.

Nausea and Vomiting: Blood is shunted away from the digestive system.

Vital Signs Changes: Increased pulse and respiration rates; weak, thready pulse; potential drop in blood pressure as a late sign.

Late Signs: Cyanosis around lips and nail beds.

How to check blood pressure using the auscultation method?

Position the cuff

Warp the cuff around the upper arm, about 1 inch above the elbow crease

Ensure the center of the bladder is over the brachial artery

Locate the brachial artery: use palpation to find it before placing the stethoscope

Inflate the cuff: close the bulb valve and inflate until the pulse sound disappears, then go 30 mmHg higher

Systolic pressure: slowly release air and note when you first hear tapping sounds

Diastolic pressure: continue deflating until the sounds fade to dull thuds

How to check blood pressure using the palpation method?

Position the cuff: apply the cuff as described for auscultation

Find the radial pulse: inflate the cuff until the pulse disappears, then go 30 mmHg higher

Obtain and record the systolic pressure: slowly deflate the cuff, noting the readings at which the radial pulse returns (you cannot determine a diastolic reading by palpation)

How to measure respiration rate?

Observe the Patient: Start immediately after you determined the pulse rate; look for rise and fall of the chest to count breaths.

Count Breaths: Count the number of breaths for 30 seconds and multiply by 2 to get the rate per minute.

Access Quality: Note if the breathing is normal, rapid, or slow. Normal rates for adults are 12-20 breaths per minute.

How to measure pulse?

Locate the Pulse Site: Use your first three fingers to find the radial pulse on the thumb side of the patient’s wrist, just above the wrist crease. Avoid using your thumb, as it has its own pulse.

Apply Pressure: Apply moderate pressure to feel the pulse beats. If the pulse is weak, you may need to apply more pressure, but be careful not to press down too hard, as this can close the artery.

Count the Beats: Count the pulsations for 30 seconds and multiply by 2 to determine the beats per minute. If the pulse rate, rhythm, or force is abnormal, continue counting for a full 60 seconds.

Record Observations: Note the pulse rate, rhythm, and force, “Pulse 72, regular and full” along with time of determination.

How to assess skin signs?

Color: Observe the skin color. Normal skin color should be pink. Abnormal colors include pale (indicating poor blood flow), cyanotic (bluish, indicating lack of oxygen), flushed (red, indicating fever or infection), and jaundiced (yellow, indicating liver issues).

Temperature: Feel the skin to determine if it is warm, cool, or cold. Warm skin is generally normal, while cool or cold skin can indicate shock or hypothermia.

Condition: Check if the skin is dry, moist, or clammy. Moist or clammy skin can be a sign of shock or anxiety.

Primary Assessment/Survey

The first element in a patient assessment; steps taken for the purpose of discovering and dealing with any life-threatening problems.

What are the six parts of primary assessment?

Forming a General Impression: Quickly assess the patient’s condition based on their environment, appearance, and chief complaint.

Assessing Mental Status: Use the AVPU scale (Alert, Verbal response, Painful response, Unresponsive) to determine the patient’s level of responsiveness.

Assessing Airway (A): Ensure the airway is clear. If there are obstructions, take immediate actions to clear them.

Assessing Breathing (B): Check if the patient is breathing adequately. Provide support if necessary.

Assessing Circulation (C): Evaluate the patient’s circulation, looking for signs of shock or severe bleeding.

Determining Priority: Decide if the patient needs immediate transport to a hospital or if further assessment can be done on-site.

ABC

Airway

Breathing

Circulation

Used for most patients; signs of life.

CAB

Circulation

Airway

Breathing

Used for patients who are unresponsive or not breathing, prioritizing chest compressions; no signs of life.

Chief Complaint

The statement (usually in the patient’s own words) that describes the symptoms or concern associated with the primary problem the patient is having; in emergency medicine, it is the reason the patient calls EMS.

Nature of Illness

What is medically wrong with the patient.

General Impression

Impression of the patient’s condition that is formed on first approaching the patient, based on the patient’s environment, chief complaint, and appearance.

What is the purpose of a primary survey?

To quickly identify and address any life-threatening issues, ensuring the patient’s stability before further assessment or transport.

Stable Patients

Characteristics: Vital signs are within normal ranges or slightly abnormal due to non-threatening factors (e.g., sweating on a hot day).

Care Approach: Slower pace with a more detailed secondary examination. Reassessment every 15 minutes.

Potentially Unstable Patients

Characteristics: No immediate life threats, but the condition may deteriorate.

Care Approach: Expedite transport with fewer assessments on scene. Reassessment every 5 minutes.

Unstable Patients

Characteristics: Immediate threats to airway, breathing, circulation.

Care Approach: Rapid transport with only lifesaving assessments and interventions on scene. Constant reassessment.

Three Collisions in a Crash

First collision: The vehicle hits an object, like a tree or another car. This is the initial impact.

Second Collision: The occupants inside the vehicle are thrown forward, hitting the interior, such as the steering wheel or dashboard.

Third Collision: While airbags can prevent severe injuries, they can also cause minor injuries upon impact.

Injury Mechanisms

Up-and-Over Pathway: The body moves forward and upward, risking head, neck, and chest injuries.

Down-and-Under Pathway: The body slides forward and downward, leading to potential injuries to the lower body.

Airbag Deployment: While airbags can prevent severe injuries, they can also cause minor injuries upon impact.

Law of inertia

That a body in motion will remain in motion unless acted upon by an outside force (e.g., being stopped by striking something).

Exsanguinating

Severe blood loss

Why should you avoid tunnel vision?

Someone may have shortness of breath but could be stabbed in the back

What must we always do?

Keep ourselves safe; our safety comes first before accessing our patients airway.

When assessing children, what do you do?

You start from the feet to the head; you want them to understand so use simple language and get on their level.

DCAPBLSTIC

Deformities

Contusions

Abrasions

Punctures

Burns

Lacerations

Swelling

Tenderness

Instability

Crepitus

FRANK

Bright Red

Respiratory Assessment—Physical Examination

Mental status

Level of respiratory distress

Chest wall motion

Auscultate lung sounds

Use pulse oximetry

Observe edema

Fever

Cardiovascular System—Physical Examination

Look for signs conditions may be severe.

Obtain pulse.

Obtain blood pressure.

Note pulse pressure.

Look for jugular vein distention (JVD)

Palpate the chest.

Observe posture and breathing.

Neurologic Assessment—Physical Examination

Perform a stroke scale. FAST

Check peripheral sensation and movement.

Gently palpate the spine.

Check extremity strength.

Check patient’s pupils for equality and reactivity.

Examine the patient’s gait.

Endocrine Assessment—Physical Examination

Evaluate patient’s mental status.

Observe the patient’s skin.

Obtain a blood glucose level.

Look for an insulin pump.

Look for medical jewelry.

Gastrointestinal Assessment—Physical Examination

Observe patient’s position.

Assess the abdomen.

Inspect other parts of the gastrointestinal system.

Inspect vomitus or feces if available.

Immune System—Physical Examination

Inspect point of contact with allergen.

Inspect patient’s skin for rash or hives.

Inspect the face, lips, and mouth for swelling.

Listen to the patient speak.

Listen to lungs to ensure adequate breathing.

Musculoskeletal Assessment—Physical Examination

Inspect for signs of injury, such as deformity

Palpate areas with suspected injury.

Compare sides for symmetry.

Be alert for crepitation.

Assess patient head-to-toe if there are multiple injuries or if the patient is unresponsive.

Signs of Shock in Children

Heart rate: Children rely more on heart rate to compensate for shock. A fast heart rate is a key indicator.

Blood Pressure: Children can maintain normal blood pressure even with significant blood loss due to effective vasoconstriction.

Recognition: Shock is harder to detect in children as they compensate well until they suddenly decompensate.

Key Considerations:

Capillary Refill: More reliable in children than adults.

Vital Signs Trends: Monitoring trends over time is crucial for all age groups to identify shock.

Stable Patients

For stable patients, EMTs can take a slower pace, allowing for a more detailed secondary examination on the scene. This involves thorough assessments and interventions to ensure comprehensive care.

Potentially Unstable Patients

These patients require expedited transport with fewer assessments and interventions on the scene. The focus is on quickly determining the patient’s condition and preparing for transport to a medical facility.