Pediatric Genitourinary/Gastrointestinal Disorders

1/33

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

34 Terms

Pediatric Kidneys

Kidneys are large and not well-protected from trauma.

Shorter urethra in girls increases the risk of infection.

Slower glomerular filtration rate → kidneys are less efficient at regulating fluid, electrolyte, and acid/base balance.

Smaller bladder capacity:

Infants: 20 cc to 50 cc

Adults: 700 cc

Urine Output:

Infants: 2 mL/kg/hr

Older Children: 0.5 to 1 mL/kg/hr

The renal system reaches maturity at 2 years of age.

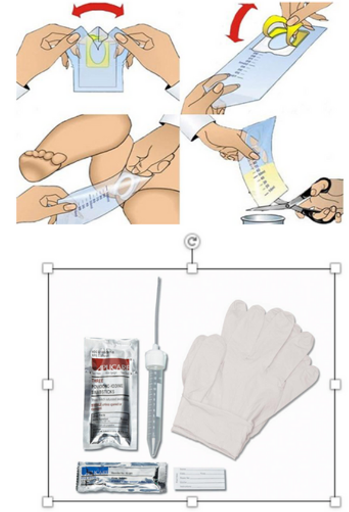

Urine Collection in Pediatric Patients

Always discuss and obtain permission for the procedure with a caregiver before catheterization.

Involve Child Life Services (CLS) for older children before invasive urine collection techniques.

Urine Bag:

Appropriate for infants and toddlers.

May be sterile or clear for urinalysis (UA).

Straight Catheterization:

Used for urinalysis (UA).

In most cases of retention or obstruction, this technique is the same as in adult patients but may be difficult due to smaller anatomy and patient cooperation.

Urinary Tract Infection (UTI)

An infection of the urinary tract, most commonly the bladder, caused by bacterial transmission via the urethra.

Females are at an increased risk due to their shorter urethra length and the proximity of the urethra to the vagina and anus.

Infant Symptoms:

Irritability

Fever

Poor feeding

Vomiting

Jaundice

Children Symptoms:

Fever

Vomiting

Dysuria

Incontinence

Urinary hesitancy and urgency

Hematuria

Abdominal pain

Flank pain

Foul-smelling urine

If left untreated → pyelonephritis, urosepsis, renal scarring, and hydronephrosis.

Diagnostic Tests: Urinalysis (UA) with reflux to culture.

UA: Positive for blood, nitrates, leukocyte esterase, white blood cells, or bacteria.

Culture: Will reveal the infecting organism.

UTI: Nursing Care

Most patients will manage this at home; care surrounds education for prevention and treatment:

Ensure adequate hydration.

Avoid:

Urinary retention

Frequent bathroom breaks (*note for school-aged child).

Females:

No bubble baths or soap application to the vulva.

Wipe front to back.

Cotton underwear.

Change pads/tampons frequently during menstruation.

Void after intercourse.

Complete full course of antibiotics and return to PCP for re-check.

Pain Management:

Acetaminophen.

Ibuprofen.

Small children may void in a warm bath or with a heating pad.

Hospital Admission Criteria & Care:

Criteria: Infant <2 months—s/sx: urosepsis, immunocompromised patient, inability to tolerate oral medications.

Care: Administer antibiotic therapy, hydrate via oral or IV fluids, pain management, and antipyretic PRN.

What are Some Structural Urinary Disorders?

Hypospadias/Epispadias

Vesicoureteral Reflux

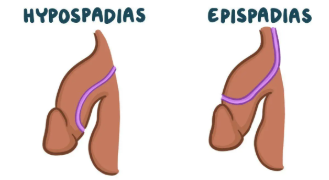

Hypospadias/Epispadias

Hypospadias:

A congenital anomaly of the male urethra, foreskin, and penis leading to the abnormal ventral placement of the urethral opening.

Epispadias:

A defect in which the urethral opening is on the dorsal surface of the penis.

Abnormal displacement has the potential to cause developmental or functional issues:

Deflection of the urinary stream.

Inability to urinate standing.

Erectile dysfunction causing intercourse difficulties.

Problems with fertility due to improper deposition of sperm.

Circumcision is contraindicated before surgical repair.

Hypospadias/Epispadias: Nursing Care

Surgical repair occurs 6 to 12 months of age and is usually outpatient.

Post-Operative Care—Caregiver Support and Education Surrounding:

Pain Medication Administration:

Analgesics (acetaminophen, ibuprofen)

Antispasmodics (oxybutynin).

Antibiotics are given post-op to prevent infection while the catheter is in place.

Surgical site care: Dressing stays in place for 3 days; soak it off; may apply Vaseline to outer diapers once the dressing comes off.

Double-diapering and catheter care.

When to call the provider or go to the ED: Fever, excessive bleeding, inconsolable pain, change in urine output.

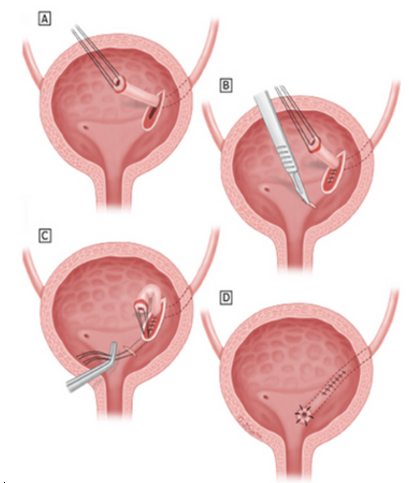

Vesicoureteral Reflux (VUR)

Retrograde passage of urine from the bladder into the upper urinary tract → renal scarring.

Potential for renal insufficiency or failure later in life.

Primary:

Congenital abnormality → Inadequate closure of the uretrovesical junction → Failure of the anti-reflux mechanism.

Secondary:

Result of high pressure in the bladder → failure of the uretrovesical junction to close.

May be caused by neurogenic bladder, obstruction, or dysfunction of the bladder.

Diagnostic Test:

Voiding Cystourethrogram (VCUG).

Grading:

Severity is graded on a I to V scale.

Grades III to V are associated with recurrent UTIs, hydronephrosis, and renal injury.

Vesicoureteral Reflux (VUR): Nursing Care

Daily administration of prophylactic antibiotics until VUR is resolved, either spontaneously or surgically.

Educate the child and caregiver about:

Proper toileting

Perineal hygiene

The need for regular urine testing and Voiding Cystourethrogram (VCUGs).

Post-Operative Care:

IVFs—1.5 maintenance rate to promote urinary output.

Strict I & Os.

Foley and stents may be in place—urine will be bloody for 2 to 3 days post-op.

Administer analgesics and antispasmodics.

Ambulate and advance diet as tolerated.

What are Some Acquired Urinary Disorders?

Nephrotic Syndrome

Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis

Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS)

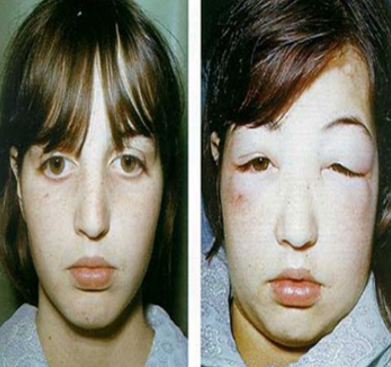

Nephrotic Syndrome

Increased permeability across the glomerular filtration barrier → plasma protein through the basement membrane → loss of protein in the urine and decreased protein and albumin in the serum.

Hypoalbuminemia → a change in osmotic pressure → fluid shifts into interstitial tissue → shift in volume prompts kidneys to conserve water and sodium → edema.

Primary:

This syndrome occurs in the absence of disease.

It includes idiopathic nephrotic syndrome, which is the most common form (90% of patients).

Secondary:

This syndrome is associated with disease or is secondary to another process that causes glomerular injury (e.g., SLE, Henoch-Schonlein Purpura, Sickle Cell Disease, Infective Endocarditis).

Signs & Symptoms:

Nephrotic-range proteinuria—urinary protein excretion greater than 50 mg/kg per day.

Hypoalbuminemia—serum albumin concentration less than 3 g/dL (30 g/L).

Edema (generalized—anasarca).

Hyperlipidemia.

Nephrotic Syndrome: Nursing Care

Promote Diuresis:

Administer corticosteroids (prednisone) and diuretics (furosemide) as ordered.

Daily weights.

Monitor urine output and proteinuria.

Regular assessment of vital signs and edema.

Administer albumin as ordered for severe hypoalbuminemia.

Prevent Infection:

Give prophylactic antibiotics as ordered.

Vaccine administration—pneumococcal and varicella.

Avoid live vaccines during steroid treatment.

Nutrition:

May require fluid and salt restriction.

Encourage foods high in protein and potassium (if low from diuretics).

Child & Caregiver Support and Education:

Surrounding the course of treatment and preventing relapse by adhering to the treatment plan.

Teach how to check for proteinuria via urine dipstick.

Offer supportive resources to children distressed with appearance.

Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis

An immune complex disease that occurs after an infection.

Infection → immunologic response → glomerular inflammation and injury → can lead to uremia and renal failure.

Signs & Symptoms:

Recent infection (viral URI, strep)

Fatigue

Proteinuria

Hematuria

Decreased glomerular filtration rate

Retention of sodium and water → edema & hypertension

Nursing Care:

Antibiotic therapy if strep infection is present.

Monitor and manage hypertension with antihypertensives (e.g., labetalol) and diuretics.

Sodium and water restriction.

Strict I & Os.

Cluster care to allow for rest.

May require dialysis for life-threatening fluid overload refractory to treatment, uremia, elevated K+ resistant to treatment.

Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS)

Three defining features of HUS:

Hemolytic Anemia

Thrombocytopenia

Acute Renal Failure

Acquired HUS:

Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC): 90% of pediatric cases of HUS.

Ex: Undercooked beef, feces, certain animals, unpasteurized dairy.

Signs & Symptoms: Begins 5 to 10 days after diarrhea onset.

Abdominal pain

Vomiting

Diarrhea (bloody)

Hematuria

Streptococcus pneumoniae: 5% to 15% of pediatric cases of HUS.

Develops following a pneumococcal infection; the pneumococcal vaccine is protective against many strains.

Initial disease in patients is more severe (higher mortality rate) than in patients with STEC.Signs & Symptoms:

Pneumonia

Usually with empyema (collection of pus outside the lungs) or effusion

Dyspnea

Respiratory distress

Fever

Cough

Patients may progress to severe AKI or renal failure; 50% of patients will need dialysis.

Neurologic Signs & Symptoms (can be seen in about 20% of patients):

Altered mental status

Seizures

Coma

Stroke

HUS: Nursing Care

Care is Supportive:

Anemia:

Slow infusion of PRBCs (for Hgb <6) over 3 to 4 hours to prevent fluid overload.

Thrombocytopenia:

PLT transfusion if significant bleeding is present.

Maintain Appropriate Fluid Balance:

This is tricky as patients with HUS may have increased (oliguria or anuria) or decreased (vomiting, diarrhea) intravascular volume.

If decreased intravascular volume—administer fluids to restore euvolemic state.

If increased intravascular volume—administer diuretics and antihypertensives as ordered.

Monitor Kidney Function, Prevent Further Injury:

Labs—CBC, CRT, BUN, electrolytes

Avoid administration of nephrotoxic medications.

Manage HTN:

Restore euvolemia, administer diuretics or antihypertensives as ordered.

Patient May Require:

Education should be given surrounding the risk of transmission (STEC is shed for 7 days; longer in younger patients for 3 weeks).

Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children

Upper GI Tract:

The lower esophageal sphincter is fully developed at 1 month of age.

Stomach capacity is 200 mL, with gastric emptying faster than in adults.

Adults: 2,000 mL to 3,000 mL capacity.

Lower GI Tract:

The small intestine is 250 cm vs 600 cm in adults.

Healthy infants have a faster intestinal transit time than adults.

The liver is ½ the size of the abdominal cavity, and the edge may be palpable on examination 2 cm to 4 cm below the right costal margin.

Immature neuromuscular function often causes stooling after eating as a result of gastrocolic reflux.

By 2 years of age, voluntary control of bowel movements occurs.

Meconium is the first stool and appears black in color, sticky.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Gastroesophageal Reflux:

Passage of gastric contents into the esophagus (regurgitation or ‘spitting up’).

Frequent in infants <12 months (30x/day).

Physiologic in all ages until it causes symptoms of esophageal injury or complications → referred to as GERD.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD):

Signs & Symptoms:

May be vague and include—poor weight gain (FTT—failure to thrive), feeding refusal, irritability, respiratory symptoms (cough, wheezing), neck or back arching, heme + stools.

Underlying causes must be ruled out before diagnosis (e.g., food allergies, malrotation, neurologic impairment).

Conditions Associated with GERD:

Obesity

Cystic Fibrosis (CF)

Neurologic Impairment

Prematurity

Hiatal hernia

Achalasia

GERD: Nursing Care

Administering Feedings:

Elevate the head or the head of the bed.

Keep the infant upright for at least 30 minutes after feedings.

Offer smaller, more frequent feedings; avoid overfeeding.

Thicken feeds (e.g., oat cereal).

Other Modalities:

GERD should resolve spontaneously as the infant grows.

However, with moderate to severe cases, the infant may require medication.

PPI: Omeprazole

H2 Receptor Antagonist: Famotidine

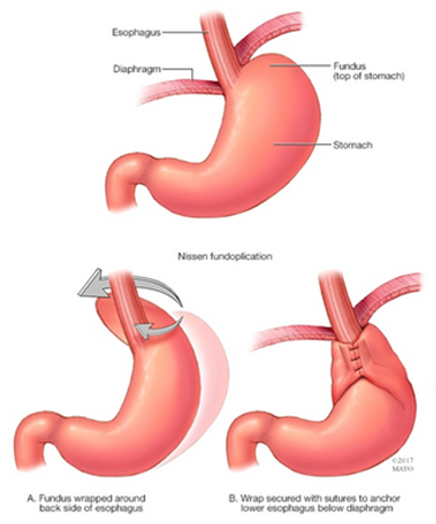

Nissen fundoplication is reserved for infants with severe GERD, refractory to the treatment above.

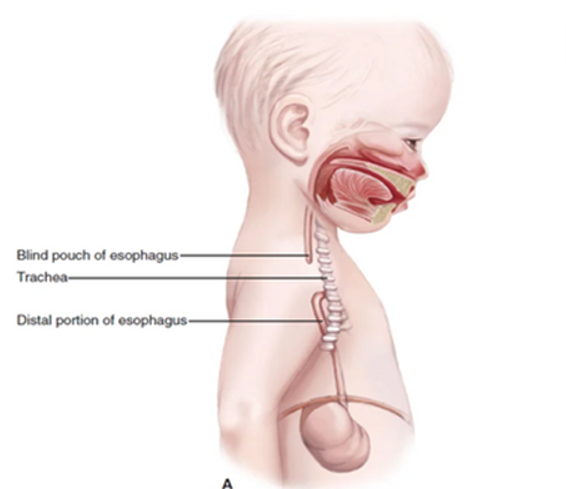

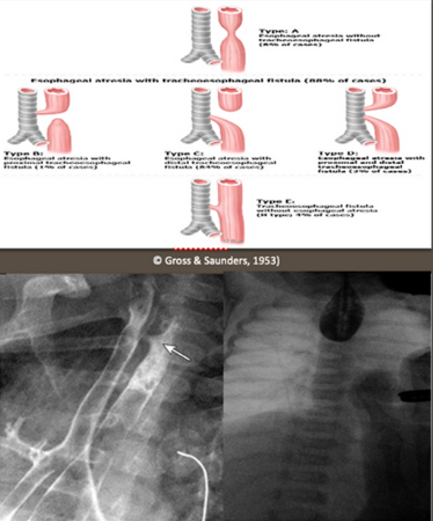

Esophageal Atresia & Tracheoesophageal Fistula (EA/TEF)

Congenital anomaly caused by a defect in the lateral section of the foregut into the esophagus and trachea (the trachea and esophagus do not separate normally during development).

Clinical presentation of TEF depends on the presence of EA.

EA: Proximal and distal ends of the esophagus do not communicate (blind pouch).

Signs & Symptoms (present after birth):

Drooling

Choking

Coughing

Cyanosis

Respiratory distress

Inability to feed (aspiration)

NGT coiled in the esophagus (cannot pass)

Abdominal distension

50% of cases have associated anomalies (VACTERAL association or CHARGE syndrome).

Diagnostic Tests:

Chest X-ray

UGI series

EA/TEF: Nursing Care

EA Post-Operative Care:

Routine post-op care

Administer parenteral nutrition, IV antibiotics

Administer PO feeds when ordered

Caregiver support and education:

Signs and symptoms to watch for and when to call the provider

PPI administration

Possibility of need for future esophageal dilations

TEF Post-Operative Care:

NPO, NGT/OGT to low continuous suction

Administration of parenteral nutrition, IVFs

PRN suction and oxygen

Comfort measures

Caregiver education

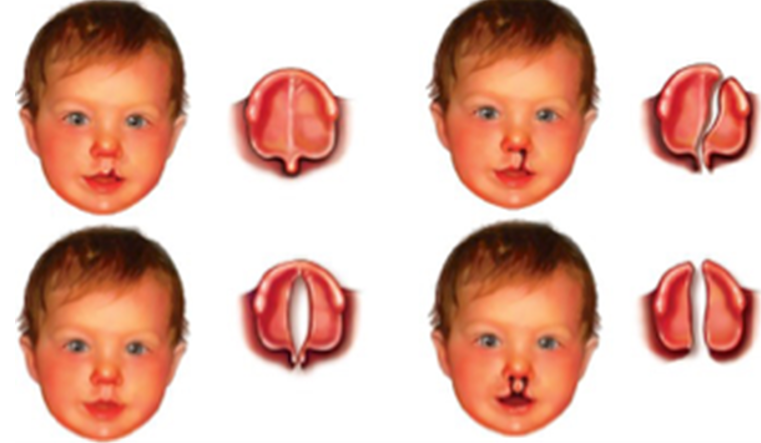

Cleft Lip & Palate

The most common congenital craniofacial abnormality (30% associated with genetic syndromes).

Infants are at higher risk of developing this if the mother:

Smokes

Takes certain medications

Is considered advanced in age

Presentation:

Many infants present with both cleft lip and palate (50%).

May present with cleft lip alone or cleft palate alone.

May be left-sided, right-sided, or bilateral.

Examination:

Cleft lip: visualized on examination.

Cleft palate: visualized on examination and palpated with a gloved finger.

Repair Time:

Cleft lip: 3 months.

Cleft palate: 6 months.

Cleft Lip & Palate: Nursing Care

Promote Nutrition:

If cleft palate is present, the infant may not be able to generate enough pressure to suck milk from the bottle or breast.

Adaptive equipment may be used to assist in feedings (squeezable bottle or modified nipple).

If cleft lip (alone) is present, the infant can feed from the bottle or breast.

Increased risk for aspiration with a cleft palate, so prevent this by covering the palate with a prosthodontic device.

Encourage Infant-Parent Bonding:

Parents may experience distress surrounding the infant's appearance and hospitalization.

Support parents in providing feedings and other care to the infant.

Provide education for anticipated surgeries.

Post-Operative Care:

Pain management with medication and comfort measures (holding, rocking, singing) — anticipate their needs.

Prevent damage to the suture line of the lip and/or palate.

The infant should lie supine, and may require a mitten or welcome-sleeve restraints.

Do not allow the infant to suck on pacifiers, plastic syringes, or straws in older children undergoing repair.

No oral suctioning (or keep it to a minimum).

Acute Viral Gastroenteritis

Intestinal Infection:

Destruction of enterocytes → shift of fluid into intestinal lumen → loss of fluid and salt in stool (diarrhea).

Intestinal injury decreases digestion and absorption.

Occurs in infants and children year-round.

Transmitted most often by the fecal-oral route by symptomatic and asymptomatic carriers.

Examples of infectious pathogens: rotavirus, norovirus, and enteric adenovirus.

Symptomatic onset depends on the virus (incubation period differs).

Primary Signs & Symptoms:

Diarrhea

Vomiting

Other Signs & Symptoms:

Fever

Abdominal pain

Myalgia

Anorexia

Patients with moderate to severe cases of this disease may experience:

Weight loss

Electrolyte imbalance

Tachycardia

Hypotension

Sunken fontanelle

Dry mucous membranes

Reduced skin turgor

Low urine output

Listlessness

Lethargy

Acute Viral Gastroenteritis: Nursing Care

Treatment is Supportive:

Fluid repletion and replacement of ongoing fluid losses.

Mild to moderate: Oral Rehydration Therapy (ORT).

Moderate to severe: IV hydration.

Antiemetic medications (Zofran).

Diet:

Complex carbs are preferred.

Avoid fatty or sugary foods (BRAT diet not necessary).

Monitoring:

Daily weights.

Electrolytes.

PO intake (strict I & Os).

Caregiver Education:

Diarrhea may last several days after discharge home.

Handwashing.

Signs and symptoms of when to call the provider or return to the ED.

Rotavirus Vaccine.

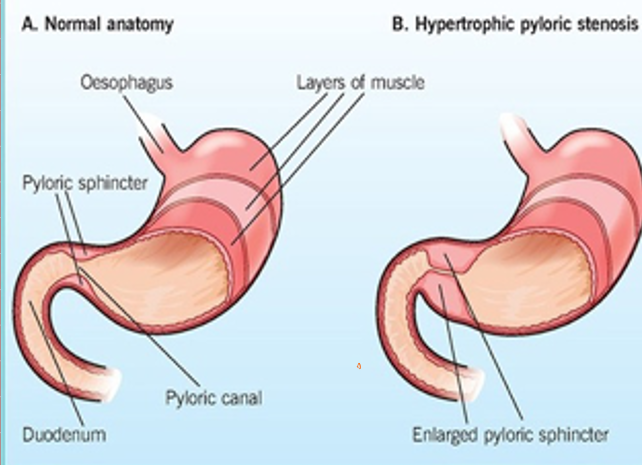

Infantile Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis

Hypertrophy of the pylorus → obstruction of gastric outlet → forceful, often projectile vomiting.

Occurs in early infancy between 3 to 6 weeks.

Vomiting occurs immediately following feeding.

Infants are irritable and hungry, wanting to be fed again soon after emesis.

Signs & Symptoms:

Failure to gain weight or weight loss

Dehydration (dry mucous membranes, no tears)

Hyperchloremic metabolic alkalosis

Palpation of ‘olive-sized’ mass in RUQ.

Diagnostic Tests:

Abdominal ultrasound will demonstrate hypertrophied pylorus.

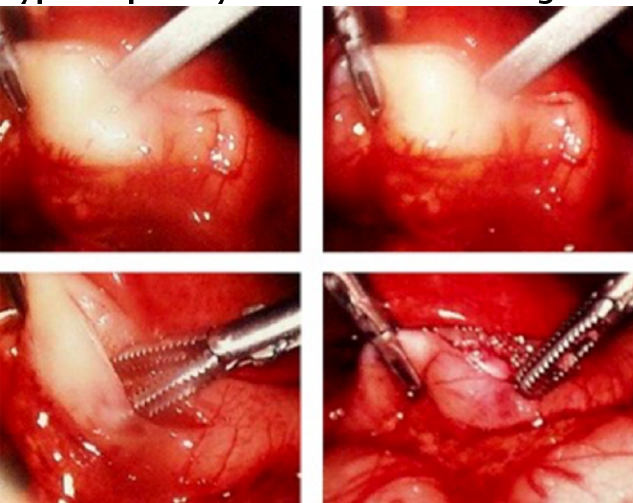

Infantile Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis: Nursing Care

Treatment is surgical: Laparoscopic Pyloromyotomy

Pre-Operative Care:

Administer IVFs to correct dehydration and electrolyte disturbances.

Bolus of NS (x1 or x2, depending on the degree of dehydration and hypochloremia).

MIVFs at 1.5 to 2x maintenance rate.

NPO before surgery.

Provide education and support to caregivers regarding surgery.

Post-Operative Care:

Resume oral feeds and continue IVFs until tolerating PO.

Strict I & Os.

Monitor surgical site.

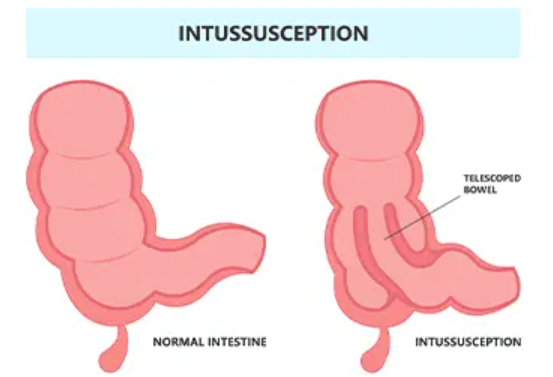

Intussusception

The most common cause of intestinal obstruction in children 6 months to 3 years of age.

Bowel telescopes into a distal portion of itself. If left untreated → edema, vascular compromise, and bowel obstruction.

Classified by location:

Ileocolic (90%)

Ileo-ileal

Jejuno-ileal

Colo-colic

May be preceded by a viral illness (URI, AOM).

Most cases are idiopathic (75%), while some may have a lead point (25%).

Signs & Symptoms:

Sudden, crampy, intermittent abdominal pain

Severe abdominal pain

Child may draw knees to chest

Vomiting

Diarrhea

Lethargy

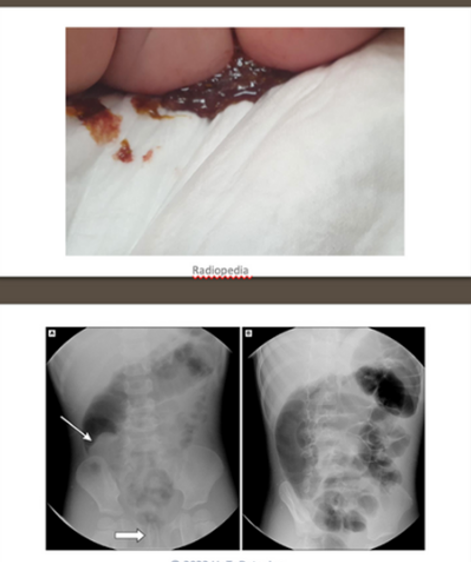

Currant-jelly stools** (mucus + blood)

Sausage-shaped mass on abdominal palpation (RUQ)

Intussusception: Nursing Care

Stable Child Without Signs & Symptoms of Perforation:

Administer IVFs.

Transport to radiology for air (pneumatic) or contrast (hydrostatic) enema.

Educate caregivers about the procedure and the likelihood of recurrence (50% recur within the first 72 hours following nonoperative reduction).

Ill-Appearing Child, Signs & Symptoms of Bowel Perforation, or Unsuccessful Nonoperative Intervention:

Emergent surgical intervention (diagnostic laparoscopy and/or exploratory laparotomy).

Administer IVFs and antibiotics.

NGT decompression.

Post-Operative Care:

Important to assess for signs and symptoms of recurrence (occurs in up to 20% of patients).

Caregiver support and education (high likelihood of recurrence).

Hirschsprung Disease

Neural crest fails to migrate completely during intestinal development → aganglionic segment of the colon → lack of propulsion of intestinal contents (functional obstruction).

The aganglionic segment may be short (rectosigmoid), long (extends proximal to the sigmoid colon), or total colonic aganglionosis.

Outcomes are worse with long-segment disease.

Associated with chromosomal anomalies (e.g., Trisomy 21).

Hallmark sign = delay or failure to pass meconium within the first 48 hours of life.

Signs & Symptoms:

Abdominal distension

Poor feeding

Constipation

Bilious emesis

"Squirt" or "blast" sign (explosive stool after rectal exam)

Hirschsprung-Associated Enterocolitis (HAEC):

Bacterial overgrowth in the bowel due to stool stasis, leading to bacterial translocation through the mucosa.

Can occur pre- or post-operatively (most common post-op complication).

May lead to intestinal perforation, peritonitis, septic shock, and death.

Signs & Symptoms of HAEC:

Fever

Vomiting

Lethargy

Explosive and foul-smelling diarrhea

Hirschsprung Disease: Nursing Care

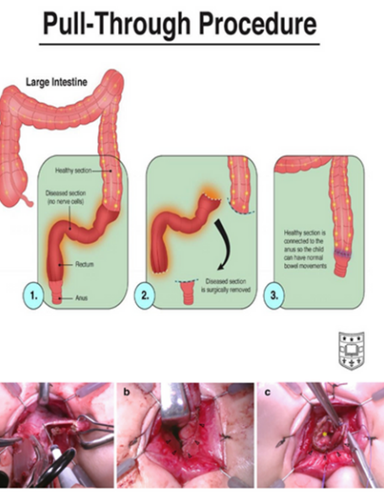

Surgical correction requires resection of the affected segment of the rectum and colon, bringing the normal ganglionic bowel down to an anastomosis with the distal rectum, close to the anus.

It may be a laparoscopic pull-through or an open (laparotomy) pull-through; multiple surgeries may be required.

Pre-Operative Care:

NPO and gastric decompression with NGT

IVFs and IV antibiotics

Rectal irrigations

Monitor for signs and symptoms of HAEC

Caregiver support and education

Post-Operative Care:

Pain management

NGT decompression until the return of bowel function (ROBF)

Monitor for signs and symptoms of HAEC (notify provider, IV antibiotics, and irrigation will need to be started)

Surgical site care and ostomy assessment/site care if present

Caregiver support and education

Anorectal Malformation (Imperforate Anus)

Anal tract fails to develop:

A normal opening is absent → the colon empties into the perineum or towards the vagina (female patients) or into the urinary system (male patients).

Atresia may be present: the rectum is a blind ending with no connection or external opening.

50% to 60% of patients have an associated anomaly (VACTERL), so all newborns with this malformation need a complete VACTERL workup:

Vertebral—tethered cord, scoliosis, myelomeningocele

Anal—atresia

Cardiac—ASD, PDA, tetralogy of Fallot

GI—tracheoesophageal fistula

Renal anomalies—vesicoureteral reflux

Limb—abnormalities

Anorectal Malformation (Imperforate Anus): Nursing Care

If a fistula is present:

Prepare and transport for diagnostic tests (ECG, chest X-ray, renal ultrasound, etc.).

Perform rectal dilation as ordered.

Provide caregiver support and education.

The infant will need eventual surgical repair (at 3 months), instructions on performing dilations at home, and knowledge of the signs and symptoms of inadequate dilation.

Provide typical newborn care.

Infants without a fistula require surgery following birth (also those with a urinary fistula or cloaca):

First surgery—colostomy to divert stool and gas.

Second surgery—posterior sagittal anorectoplasty.

Final surgery—colostomy reversal.

Pre-Op:

Administer antibiotics.

Maintain a limited clear or breastmilk diet 24 hours before surgery.

Continue dilations.

Post-Op:

Routine post-op care (pain management, advance diet as tolerated, monitor surgical site).

Ostomy care (for the first and second surgeries).

Apply bacitracin to the surgical site.

Nothing per rectum (for the final surgery).

Gastroschisis & Omphalocele

Gastroschisis:

Herniation of the abdominal wall contents through a ventral abdominal wall defect, to the right of the umbilicus, with umbilical cord insertion to the left of the defect.

Not enclosed within a sac → exposure to amniotic fluid → thickening of herniated organs, and peel may be present.

Increased risk in infants of young mothers (<20) and maternal obesity.

Omphalocele:

Full-thickness, midline abdominal wall defect that allows evisceration of the abdominal contents into an external peritoneal sac.

The umbilical cord inserts into the omphalocele membrane, not the abdominal wall.

Pulmonary hypoplasia may be present.

Associated with advanced maternal age and infants with chromosomal anomalies (trisomy 13, 18, and 21; Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome).

Defects are usually larger than gastroschisis.

Gastroschisis & Omphalocele: Nursing Care

Gastroschisis:

Cover the exposed viscera with a bowel bag to maintain temperature and prevent fluid losses.

Observe the bowel for decreased perfusion (dusky, cool appearance).

Position to the left if there is concern for vascular compromise.

Insert an OGT and place it to suction.

Position the infant on the right side to reduce tension on the mesentery.

Resuscitate with IVF bolus, then administer MIVFs at a regular rate.

Administer antibiotics and maintain strict I&Os.

Prepare for silo replacement (staged closure) or operative intervention (primary repair).

Post-Operative Care:

Pain management.

OGT until return of bowel function (ROBF).

Advance feedings once bowel function returns.

Strict I&Os.

Monitor for signs and symptoms of abdominal compartment syndrome.

Omphalocele:

Cover the sac with sterile gauze or a bowel bag up to the infant’s chest.

Observe the bowel for decreased perfusion (dusky, cool appearance).

High risk for intestinal atresia.

Insert an OGT and place it to suction.

Administer IVFs and antibiotics; maintain strict I&Os.

‘Paint and wait’ technique is used if the defect is too large for a primary repair or if the infant is too unstable for surgery.

Application of bacitracin ointment to the sac allows eschar formation, then epithelialization over time → eventual ventral hernia that can be repaired later in life.

Prepare for silo placement (staged closure) or operative intervention (primary repair).

Post-Operative Care:

Pain management.

OGT suction until ROBF.

Advance feedings once bowel function returns.

Strict I&Os.

Monitor for signs and symptoms of abdominal compartment syndrome.