week 5- pancreas, lower GI inflammation & most GI pharmacokinetics

1/83

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

84 Terms

what causes mucosal inflammation?

autoimmune (eg. IBD), Infective, disuse/diversion colitis, ischemic colitis, drug-induced, luminal occlusion

colitis= inflammation of colon

what causes lumenal obstruction and what are its 2 categories?

•Lymphoid hyperplasia

•Faecolith (hard, stone-like mass of calcified fecal matter)

•Foreign body (faeces)

•Tumour

2 categories:

Chemical-induced inflammation

Bacterial-induced inflammation

describe the presentation of Lower GI inflammation

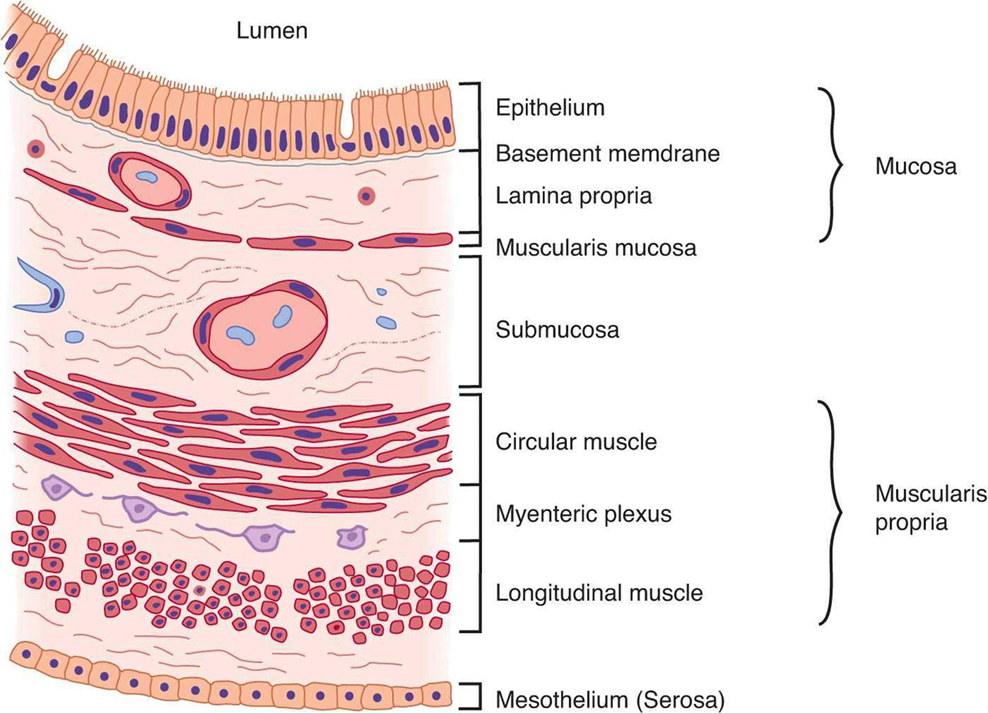

Mucosal Inflammation

•Mucosal disruption

•Bleeding

•Bacterial translocation

•Reduced mucosal function

•Secretory/ reduced absorption -> diarrhoea

•Nutritional failure

Transmural Inflammation

•Peritonitis/ perforation

•Acute obstruction

Late Presentation

•Stricture/ fibrosis

•Fistulation

•Cancer

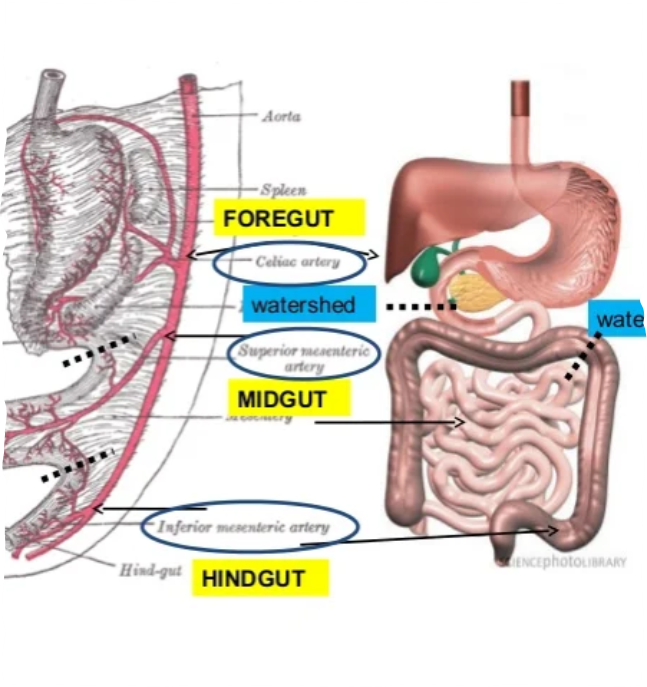

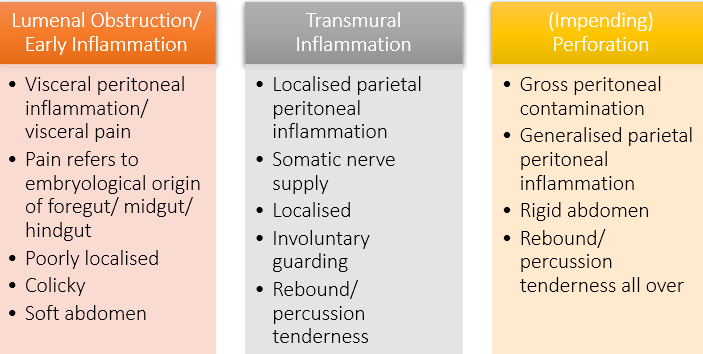

explain the evolution of abdominal findings

describe the Clinical course and histological differences between Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn's diseases and determine the role of surgery in management of IBD (UC and Crohn’s are 2 examples of IBD)

Ulcerative Colitis | Crohn's Disease | |

Site | Colon Continuous | Entire GI tract, including perianal Skip lesions |

Inflammation | Mucosal/ submucosal Involves mesentery No granulomas | Transmural Presence of granulomas |

Intent of surgery | Curative | Management of complications (strictures, fistulae, abscess) |

explain the surgical considerations in Ulcerative Colitis

•Approx. 10% of patients within 10 years will require surgery

•Surgery is curative

•Indications

Fulminant/ toxic colitis

Medical refractory

Patient preference

Complications (dysplasia, cancer...)

•Extent of surgery is dependent on presentation

Emergency/ urgent => subtotal colectomy

Elective => panproctocolectomy

•Can consider restorative procedure

(A panproctocolectomy removes the entire colon and rectum, while a total colectomy removes only the entire colon, leaving the rectum intact)

explain the surgical considerations in Crohn’s disease

Up to 75% of patients with Crohn's disease will eventually require surgery

•Not curative as may recur anywhere

•Intentions of surgery

Relieve complications

Maintain quality of life

Preserve gut length and nutritional competence

•High risk of complications, including fistulation/ intestinal failure

•Generally not feasible to perform a restorative procedure following proctocolectomy (permanent stoma)

describe the management of lower GI inflammation

•Stepwise approach – conservative > invasive

•Treat underlying pathology if possible

•Fluid resuscitation/ anticoagulation

•Antibiotics

•Immunosuppression

•Cessation of offending drug

•In event of failure, surgery not always required

•Interventional radiology

•Sometimes surgery is the answer!

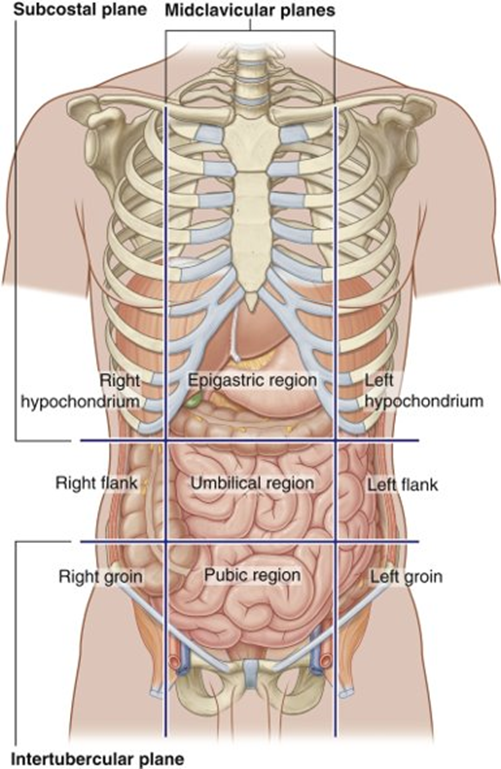

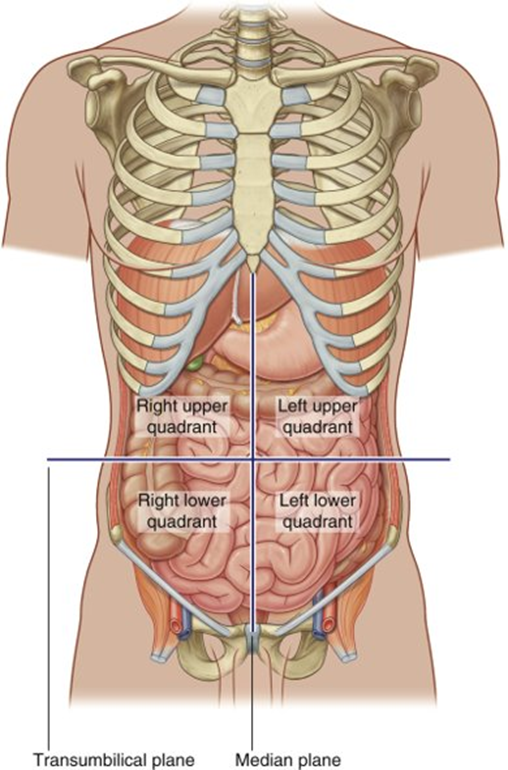

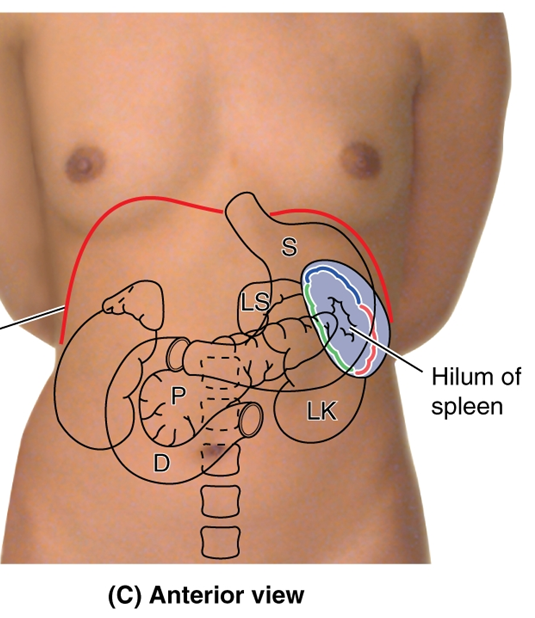

name the regions where the duodenum, pancreas and spleen are found

Duodenum

•Epigastric region, umbilical region

Pancreas

•Epigastric, left hypochondrium, umbilical region

Spleen

•Left hypochondrium

•Protected by ribs 9-11

All in the right and left upper quadrants

the duodenum and pancreas also Partly sit in the transpyloric plane

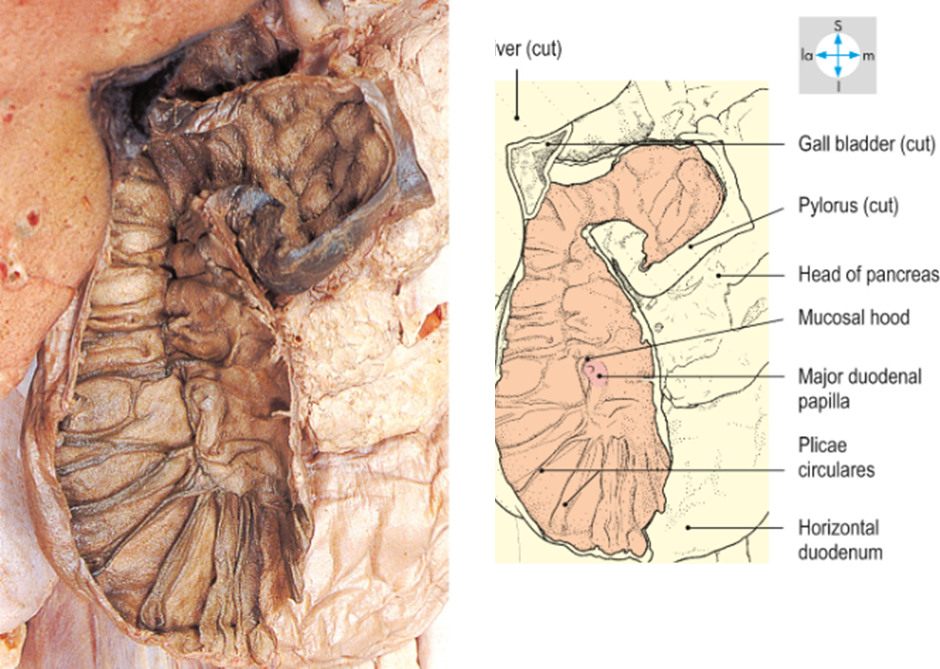

describe the gross structure of the duodenum

•From the pylorus to duodenojejunal junction.

•25cm long, C-shaped, around the pancreas, vertebral level L1-3

•Mostly retroperitoneal

4 parts: Superior, descending, inferior, ascending

1st part - superior

•5cm long

•From pylorus to superior duodenal flexure

•2.5cm intraperitoneal (duodenal cap),2.5cm retroperitoneal

2nd part – descending

•8cm long, between superior and inferior duodenal flexures

•Major (openings from the common bile duct) and minor (openings from the pancreas) papillae

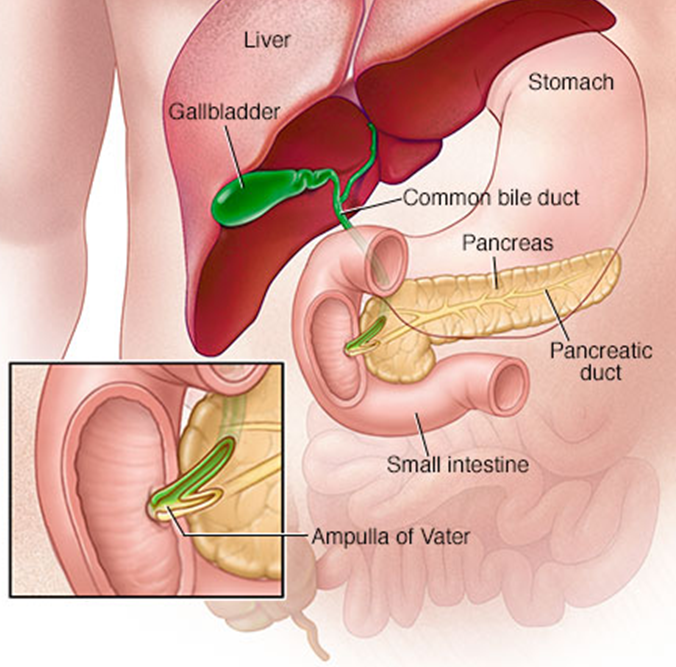

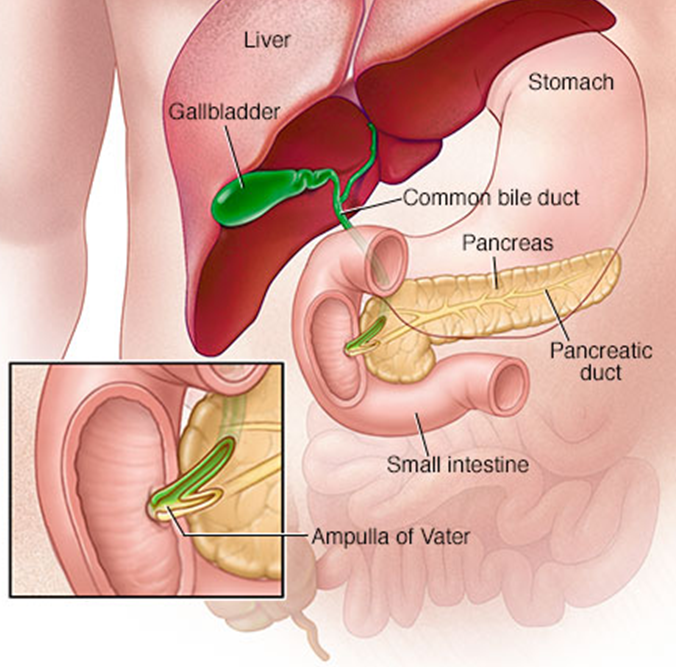

•In the major papillae the ampulla (of Vater) is found, a ductal structure that forms from the union of the common bile duct and the pancreatic duct

3rd part – inferior (horizontal)

•10cm long

•Inferior to the pancreas

•Coursing left

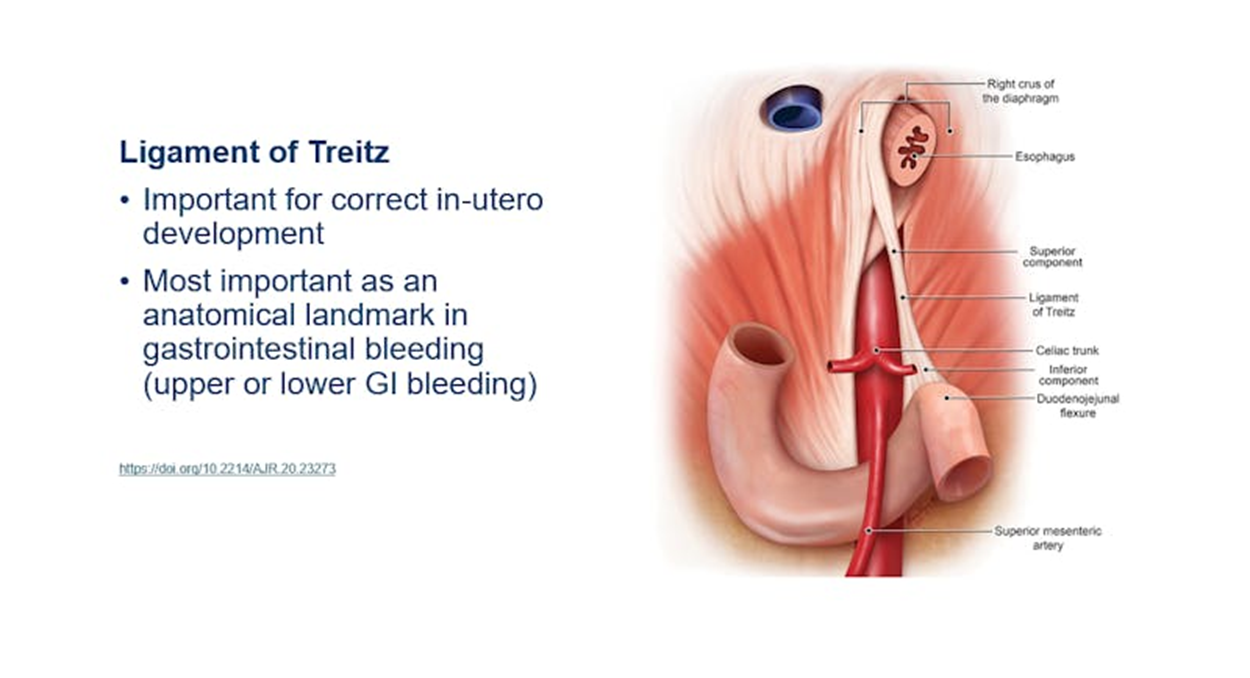

4th part – ascending

•2.5cm long

•To duodenojejunal flexure at L2

•Suspensory muscle of the duodenum attaches to the crus of the diaphragm

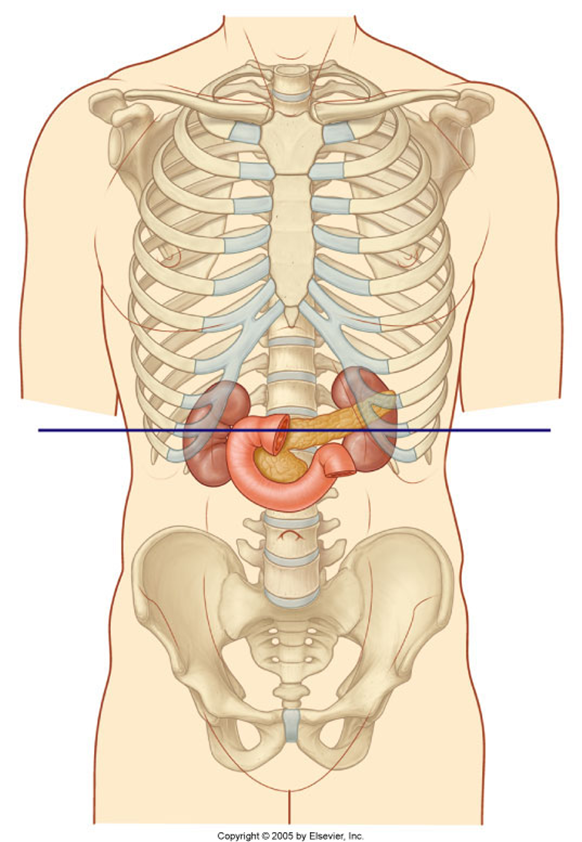

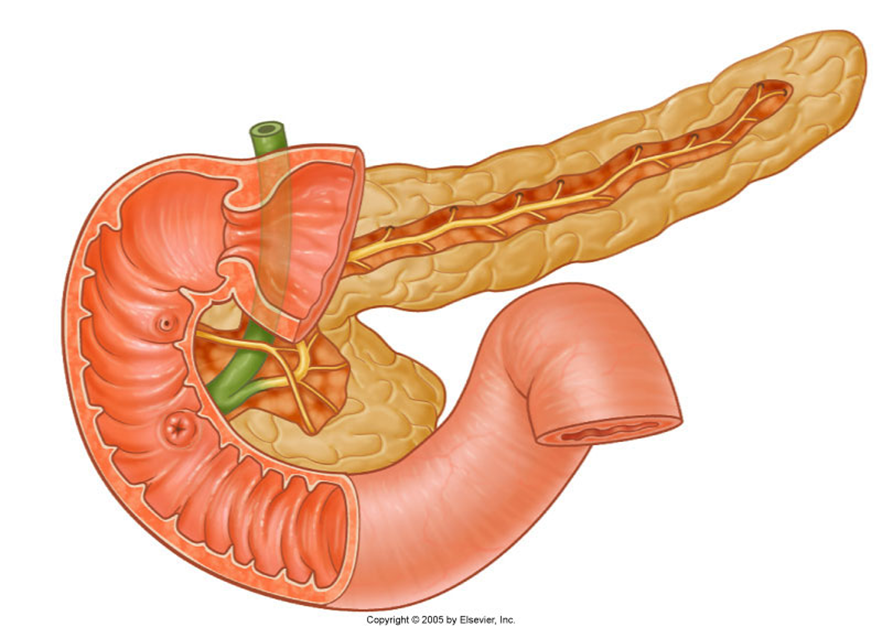

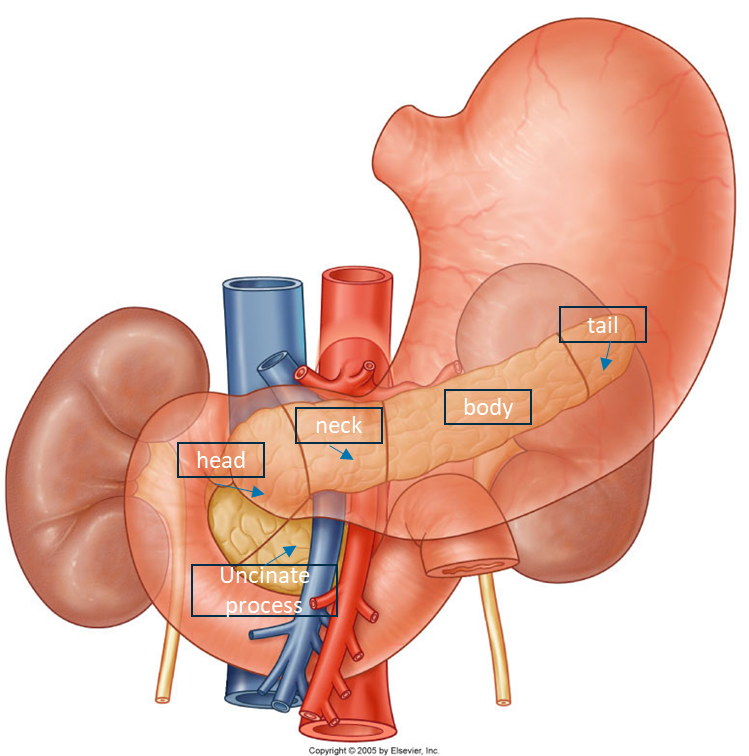

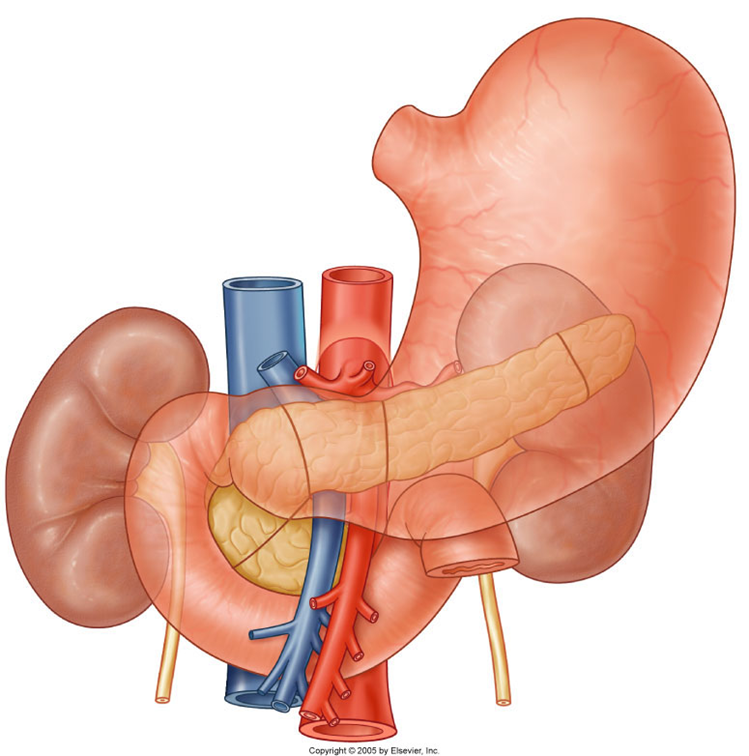

describe the gross structure of the pancreas

•Retroperitoneal organ

•15cm long, sits within C-shaped, of duodenum

•Lies obliquely at vertebral level L1-2

•5 parts: head, neck, body, tail, uncinate process

•The neck is anterior to the confluence of the superior mesenteric vein and splenic vein which come to form the hepatic portal vein

•General glandular appearance

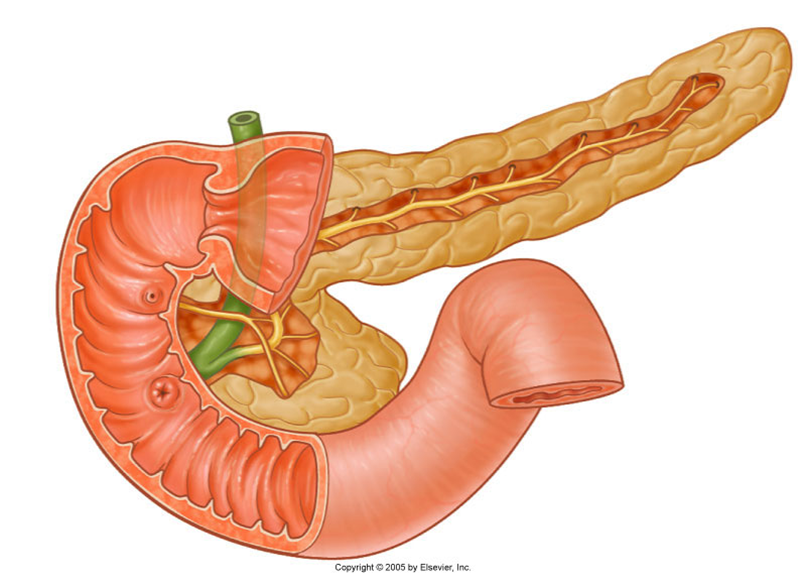

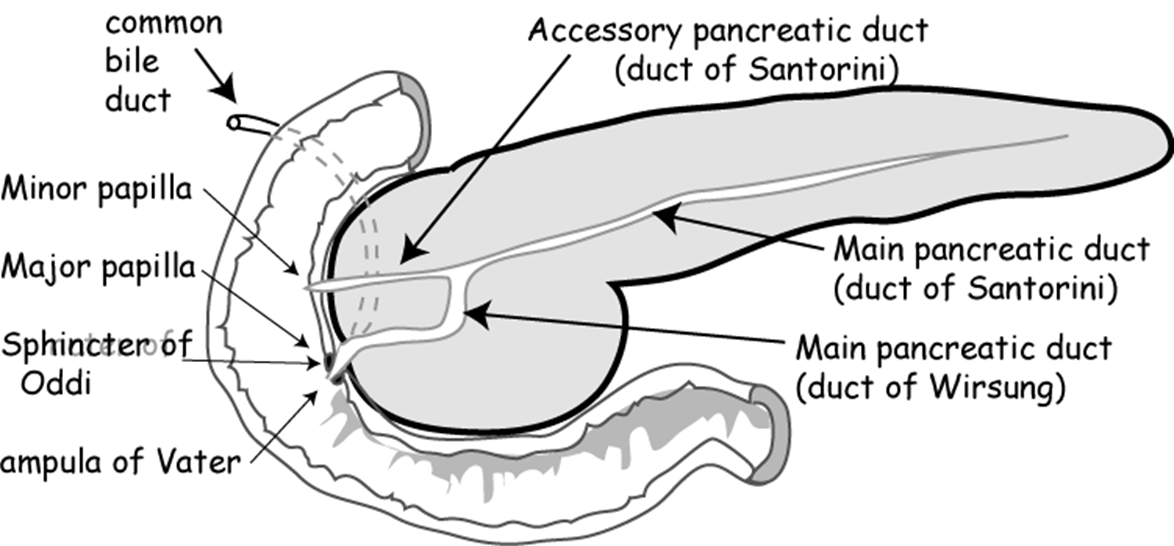

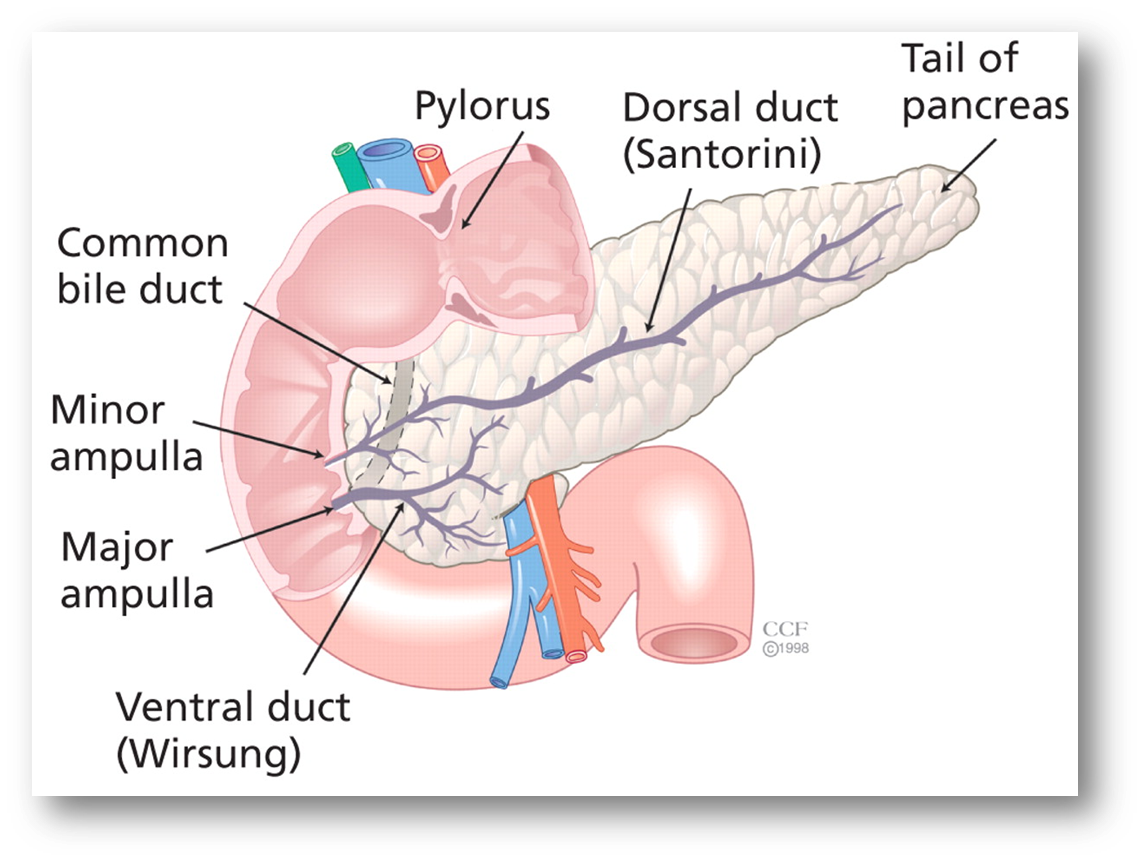

describe the Internal system of ducts

•Main pancreatic duct

(Becomes wider the closer it gets to the duodenum/terminal portion/the head)

Meets the bile duct at the hepatopancreatic ampulla

Major duodenal papilla

•Accessory pancreatic duct

Connects with main duct

Minor duodenal papilla

Sometimes not present

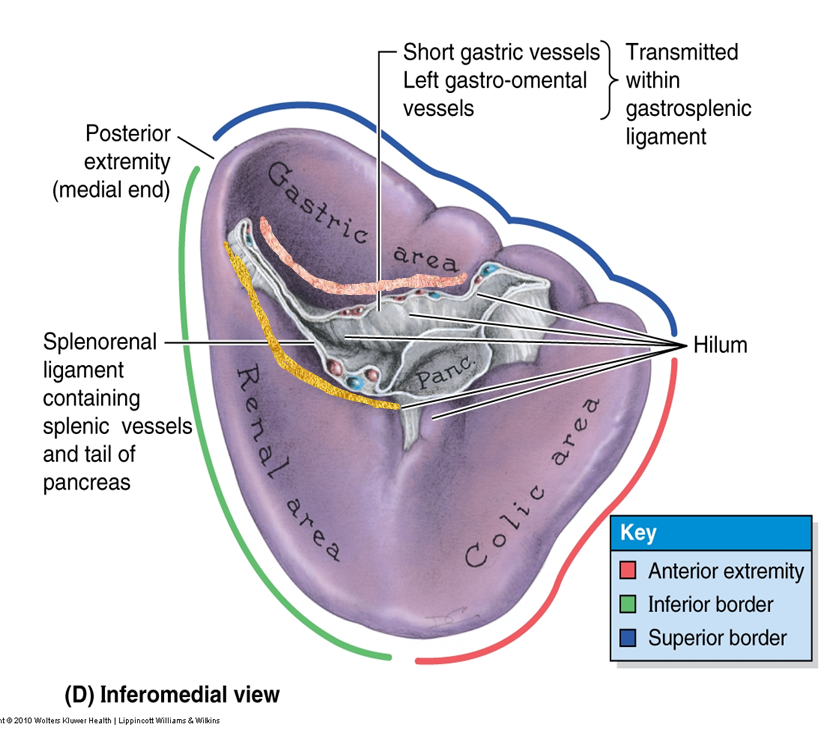

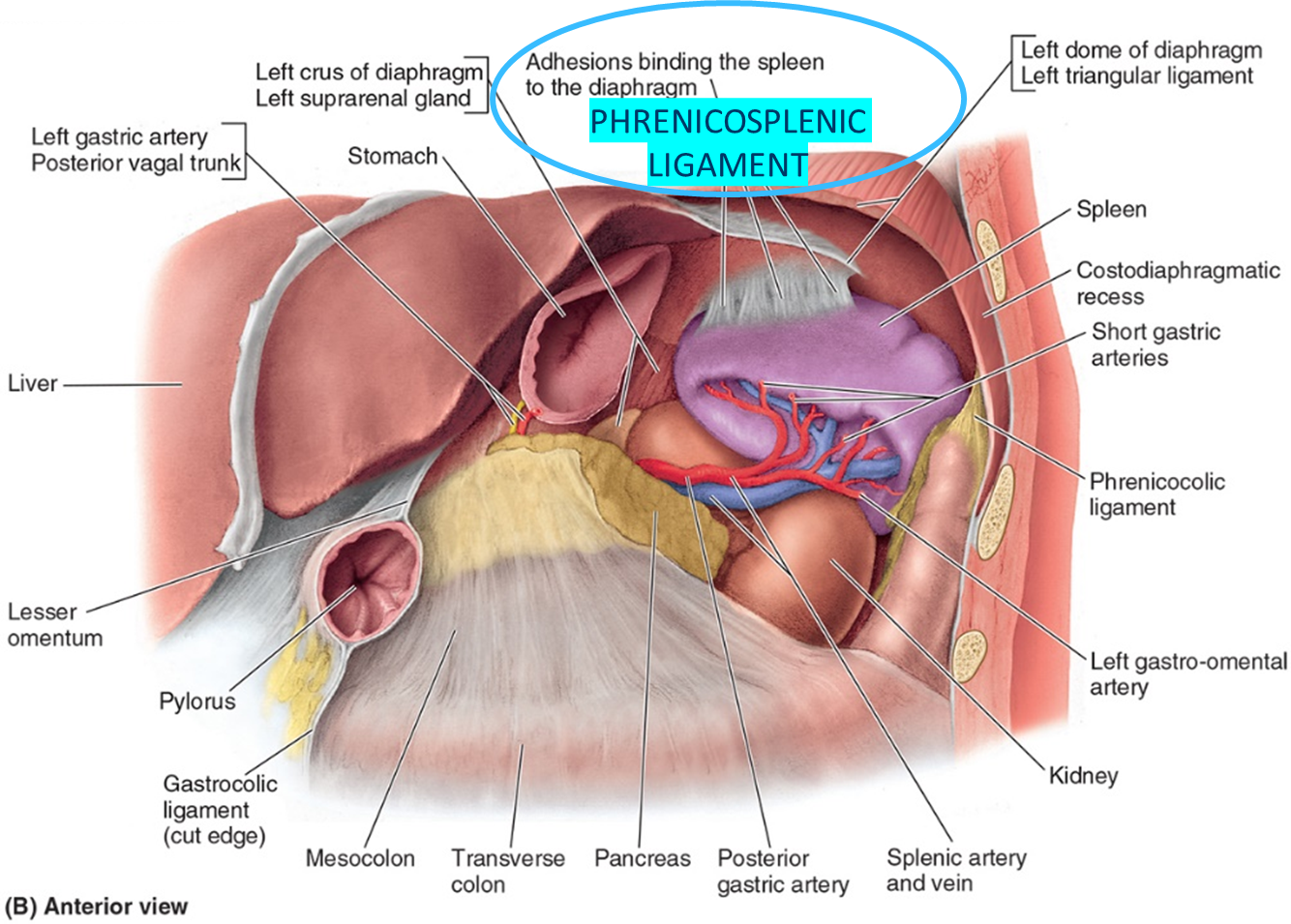

describe the gross structure of the spleen

•Largest lymphoid organ

Size varies

•Thin capsule

•Diaphragmatic and visceral surfaces

Separate ‘areas’ and surfaces

•Intraperitoneal

•Gastrosplenic ligament (thickening of the greater omentum)

•Splenorenal ligament (thickening of the greater omentum)

•Phrenicosplenic ligament

List the key anatomical structures related to the spleen.

•Stomach – anterior to the spleen

•Kidney –medial and inferior to the spleen

•Colon- at the splenic flexure, medial and anterior

•Pancreas- the tail is medial

•Diaphragm and ribs - lateral to spleen

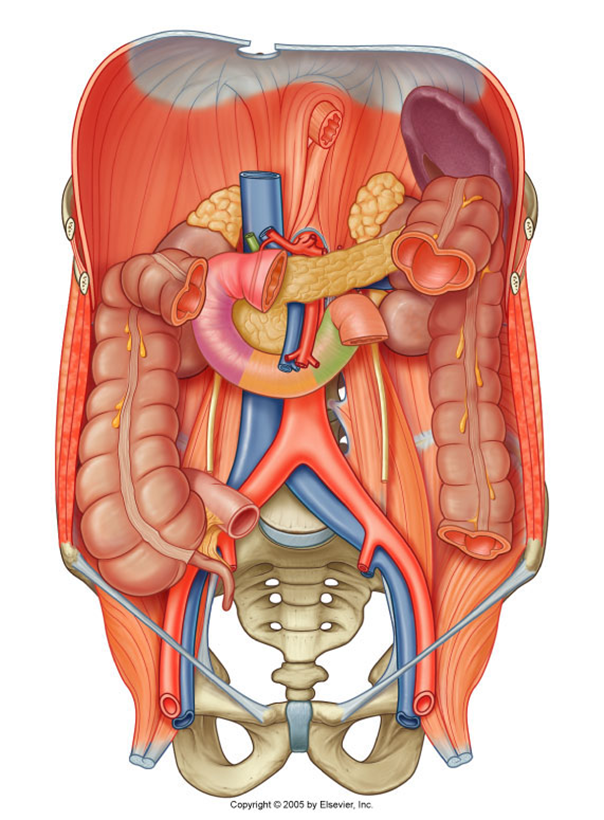

List the key anatomical structures related to the pancreas and duodenum

•Stomach- anterior to the pancreas and duodenum

•Lesser sac- anterior to the pancreas and duodenum

•Transverse colon- anterior to the pancreas and duodenum

•Aorta/IVC- posterior to the pancreas and duodenum

•Kidney/ureter- closely associated with the superior and descending parts of the duodenum, and lateral to the head of the pancreas

•Gall bladder- anterior to the first part of the duodenum

•Bile duct- duct within/posterior to pancreas, posterior to duodenum

•Superior mesenteric artery/vein- posterior to the neck and body, but become anterior to the head and uncinate process of the pancreas, anterior to the duodenum

•Celiac trunk- superior to the pancreas

•Gastroduodenal artery- posterior to the superior portion of the duodenum, superior to pancreas

•Splenic vein- posterior to the pancreas

•Hepatic portal vein - posterior to the pancreas

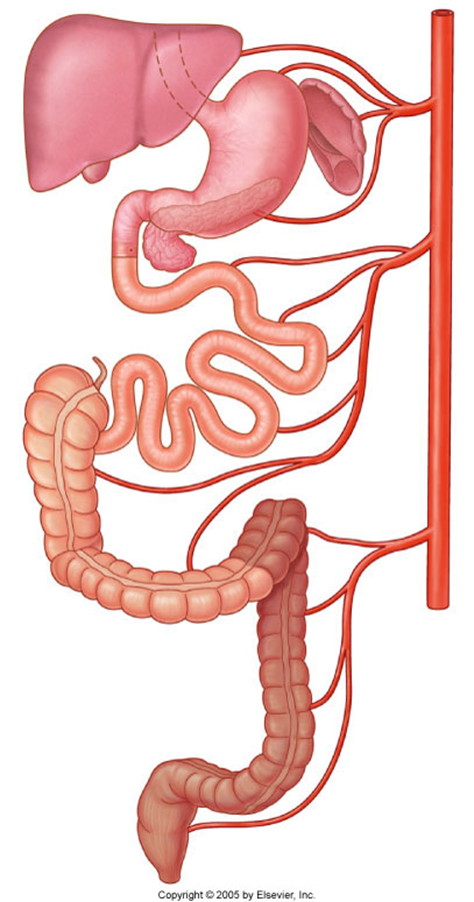

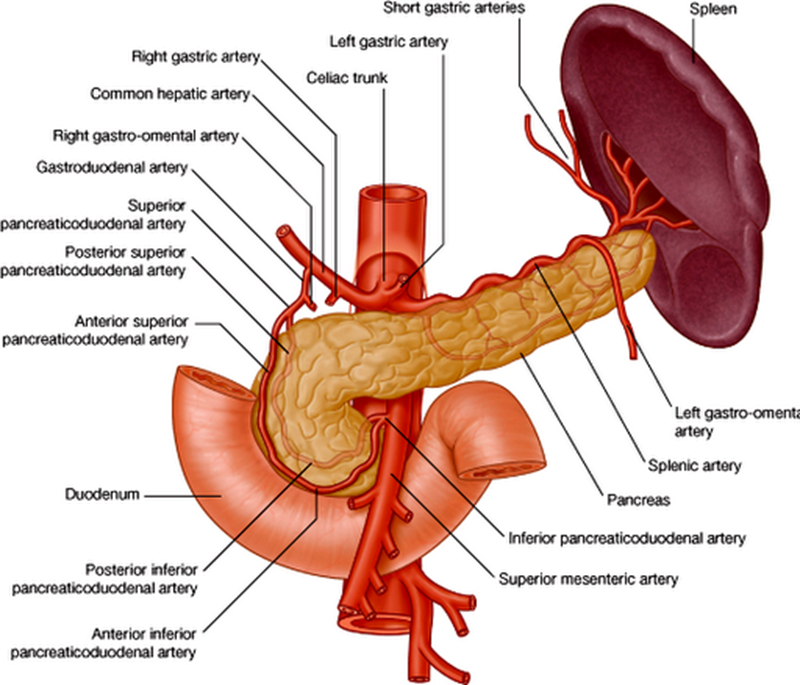

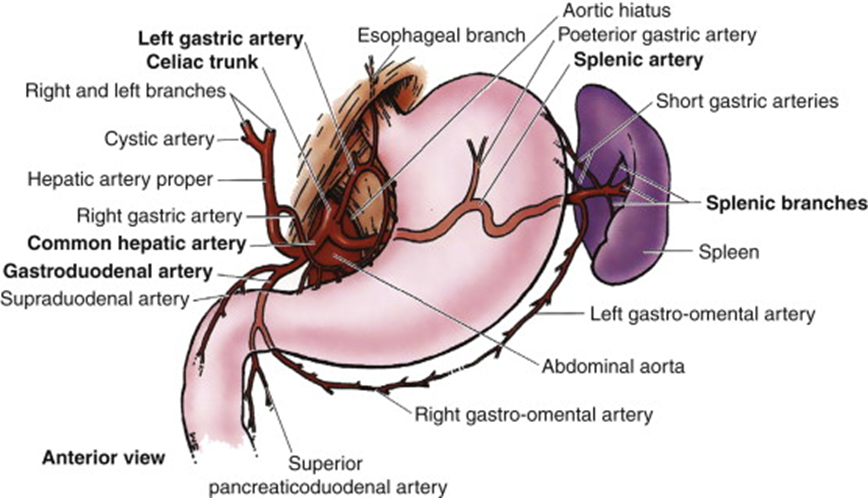

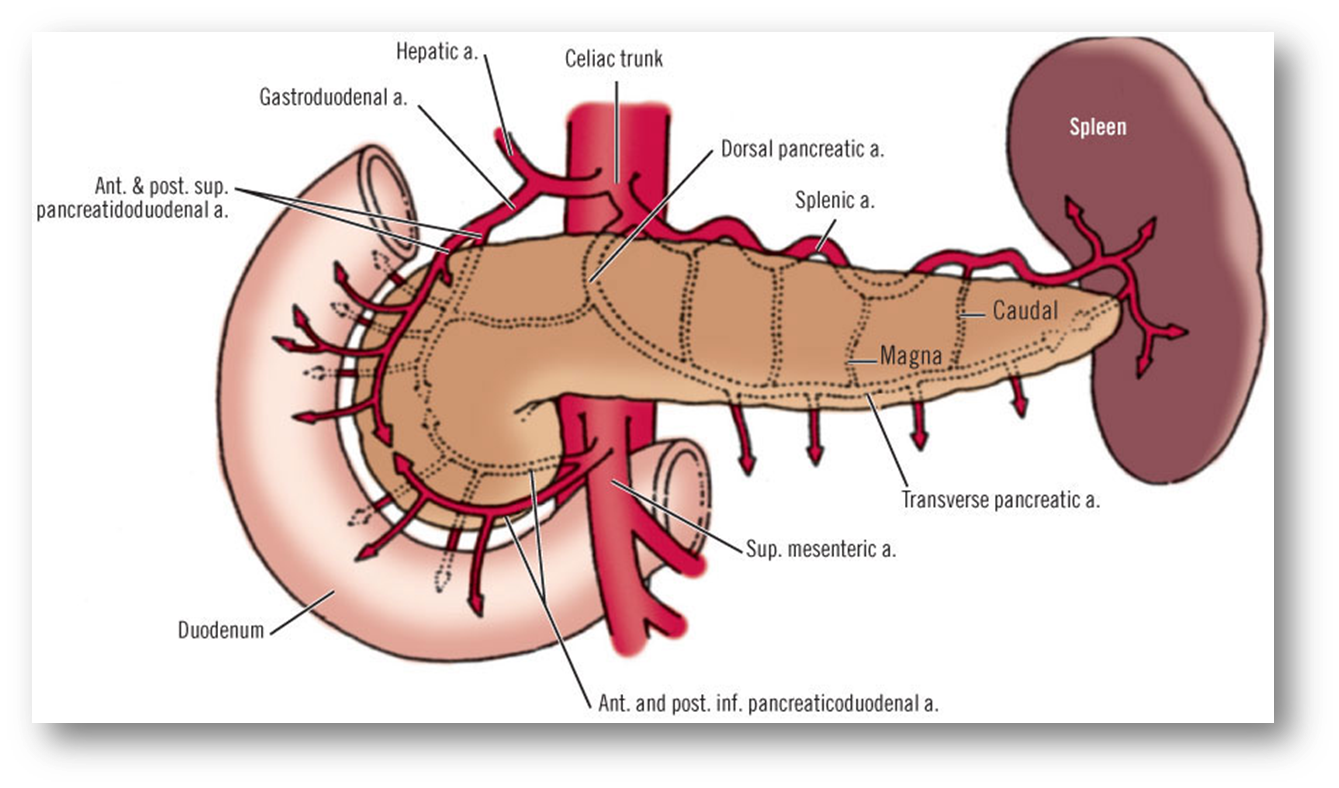

describe the blood supply of the spleen, pancreas and duodenum

Celiac Trunk

•Splenic artery – spleen

•Dorsal pancreatic artery/pancreatic branches – pancreas neck/body/tail

•Gastroduodenal artery

•Anterior/posterior superior pancreaticododenal arteries – pancreas head/uncinate process, duodenum

•Small pancreatic branches – pancreas

•Retroduodenal branches/supraduodenal artery – proximal duodenum

it only supplies the first 2 parts of the duodenum (superior and descending)

Superior mesenteric artery

•Anterior/posterior inferior pancreaticododenal arteries – pancreas head/uncinate process, duodenum

•Small pancreatic branches – pancreas

•First jejunal branch– distal duodenum

it only supplies the last 2 parts of the duodenum (inferior and ascending)

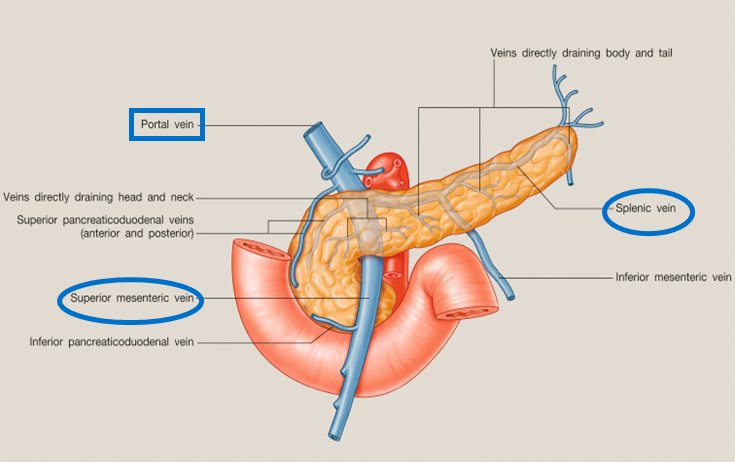

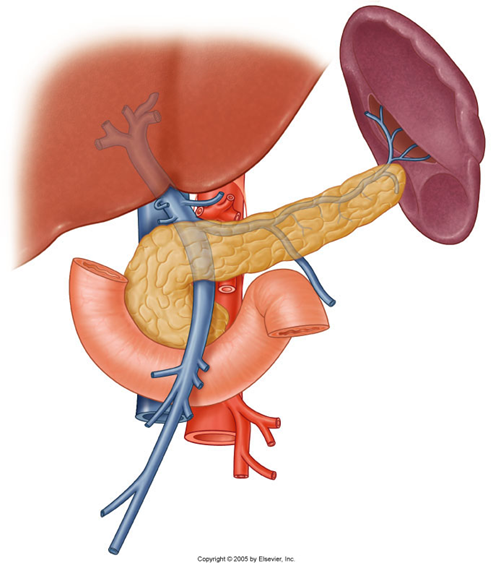

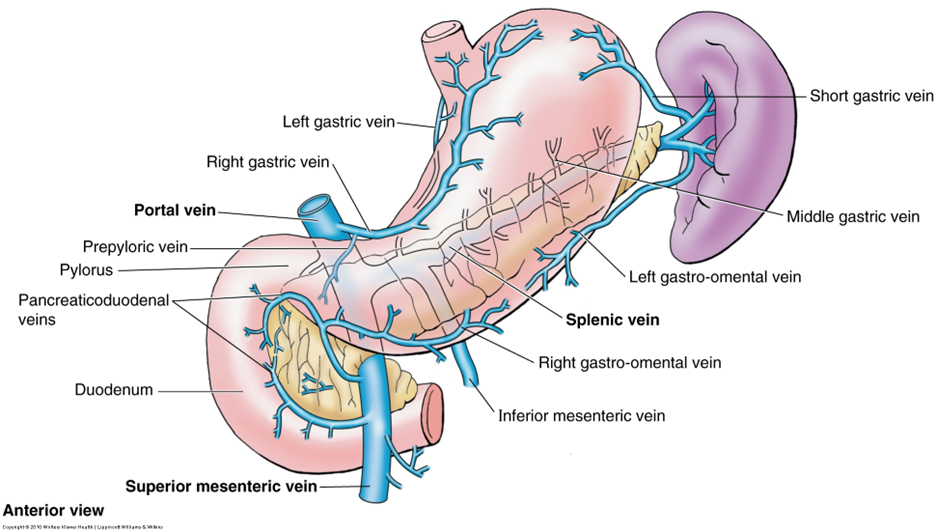

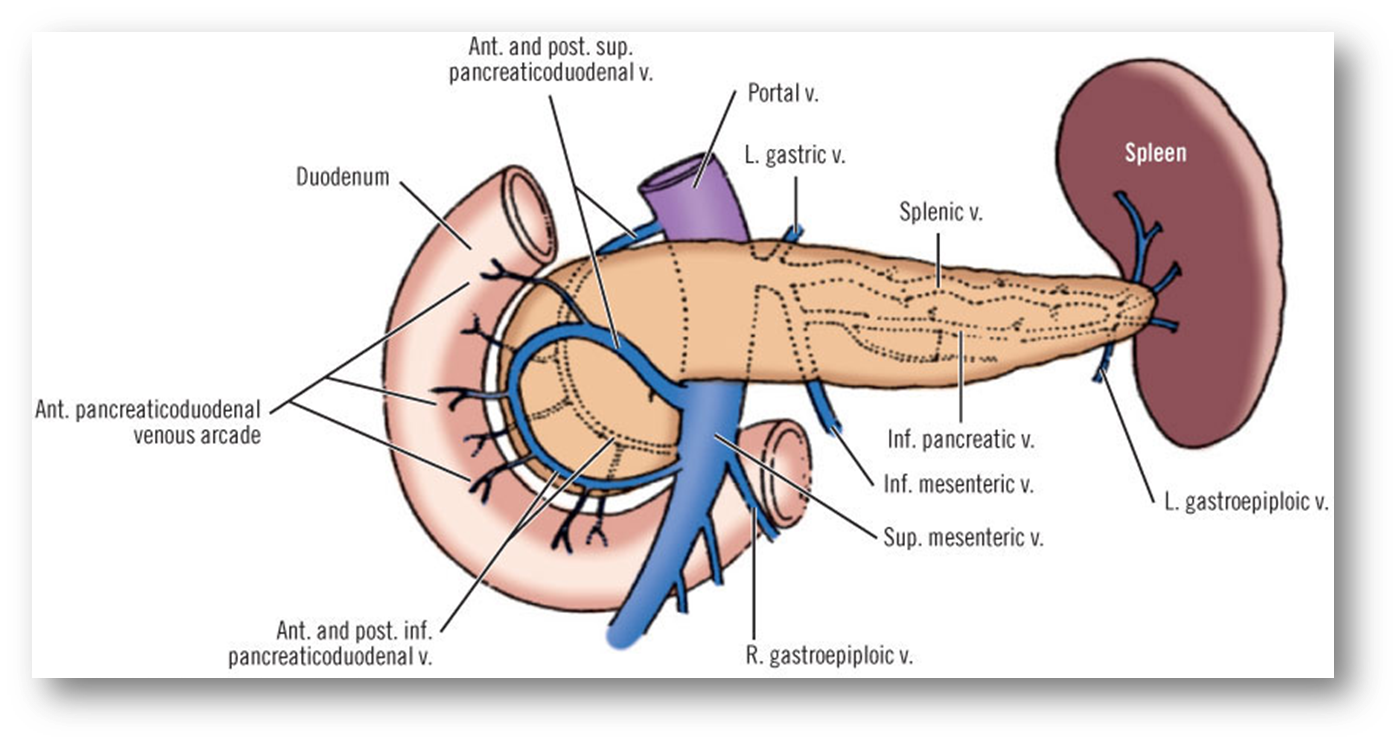

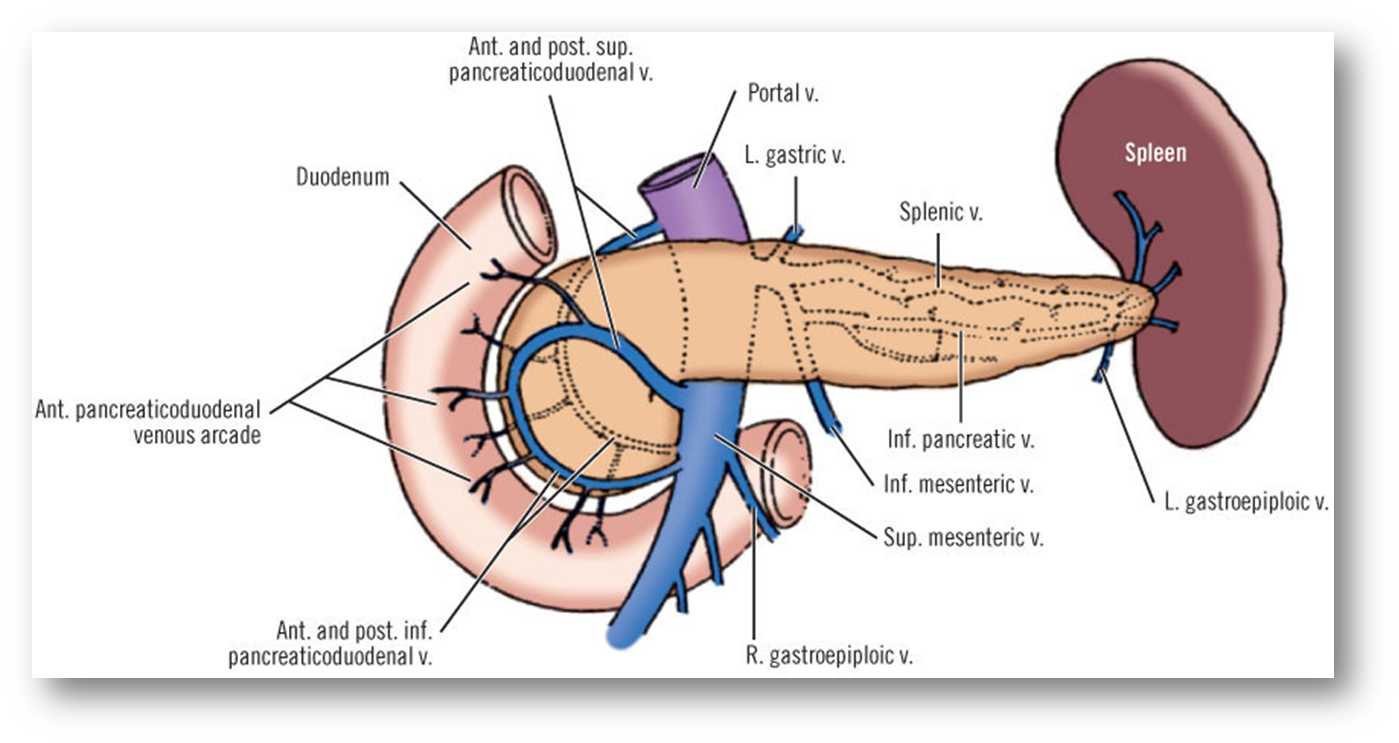

describe the venous drainage of the pancreas, spleen and duodenum

Part of the portal system (including the spleen)

Splenic vein and SMV unite posterior to pancreas neck – hepatic portal vein

Smaller branches follow pattern and names of arteries

Anterior superior PDV - SMV

Posterior superior PDV- hepatic portal vein

A/P inferior PDV – SMV

(look at picture to remember)

PDV= pancreaticoduodenal vein

SMV=superior mesenteric vein

The inferior mesenteric vein (IMV) can drain in the splenic vein (shown in the picture), or in the SMV, this is an anatomical variation

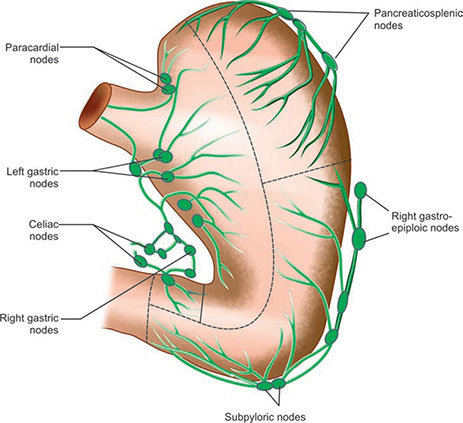

describe the lymphatic drainage of the duodenum, pancreas and spleen

Organ | Primary Nodes | Secondary Nodes | Final Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

Duodenum | Pancreaticoduodenal, mesenteric | Pyloric, superior mesenteric, celiac | Intestinal trunks → Cisterna chyli → Thoracic duct → Left venous angle |

Pancreas | Peripancreatic Ring Nodes (N1) Head: Pancreaticoduodenal Body/Tail: Pancreaticosplenic | These N1 nodes drain into the axial nodes located around the coeliac, aorta and SMA | Intestinal trunks → Cisterna chyli → Thoracic duct → Left venous angle |

Spleen | Pancreaticosplenic | Celiac | Intestinal trunks → Cisterna chyli → Thoracic duct → Left venous angle |

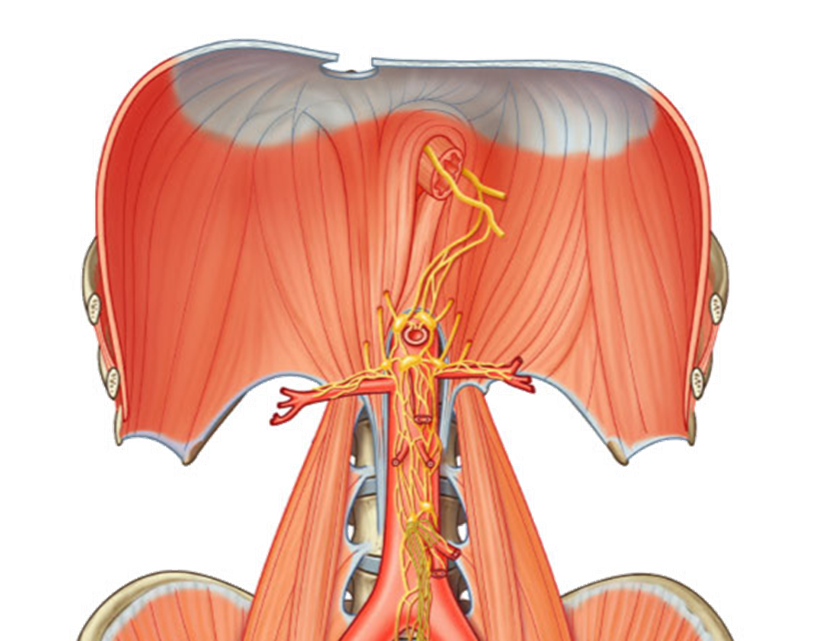

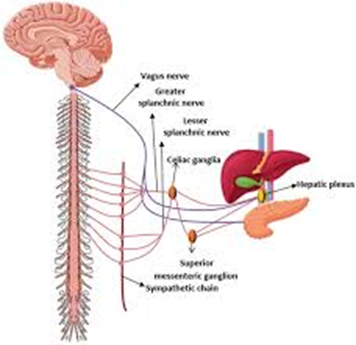

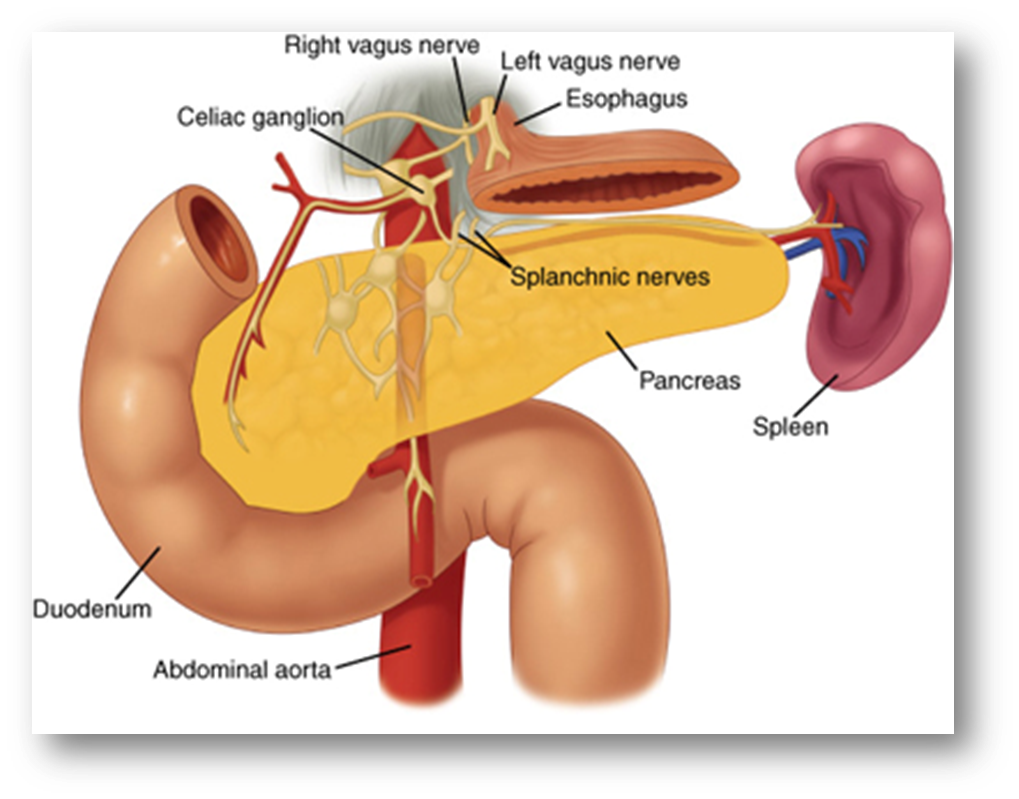

outline the nerve supply of the duodenum, pancreas and spleen

Parasympathetic

•Vagal trunks

Sympathetic

•Greater and lesser splanchnic – T5-T12

the nerves travel alongside the arteries that go to each organ. They use the same path

What is the purpose of the suspensory ligament of the duodenum?

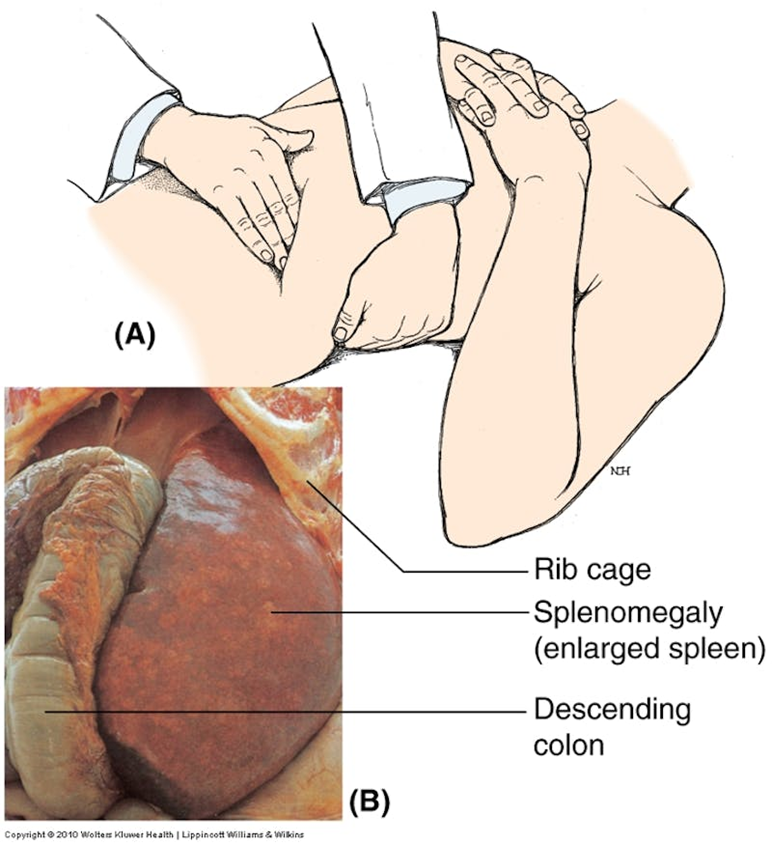

define Splenomegaly and causes

Splenomegaly - enlarged spleen

infections/ haematopoietic conditions (disorders of blood cell formation)

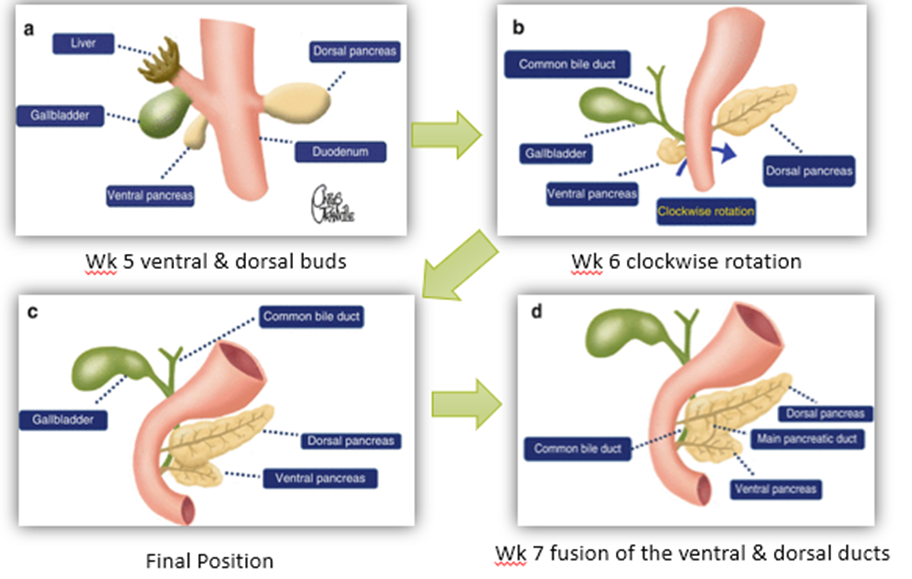

explain the embryology of the pancreas

week 5, from the ventral bud (where the gallbladder and liver also develop) & dorsal bud (comes from the foregut, MUCH larger)

overtime both buds start to mature. The dorsal pancreas grows out into the dorsal mesentery and forms the neck, body and tail of the pancreas. The tail is intraperitoneal, the rest of the pancreas is retroperitoneal.

over week 6 and 7 the ventral pancreas and the common bile duct start to rotate clockwise. The ventral and dorsal buds and ducts start to fuse.

what are the dorsal and ventral ducts of the pancreas called?

Dorsal= Duct of Santorini

Ventral= Duct of Wirsung

explain the embryological variants of the pancreas

•Pancreatic Divisum

Most common

10% of the population

Failure of fusion embryologically

Often asymptomatic

25% recurrent pancreatitis

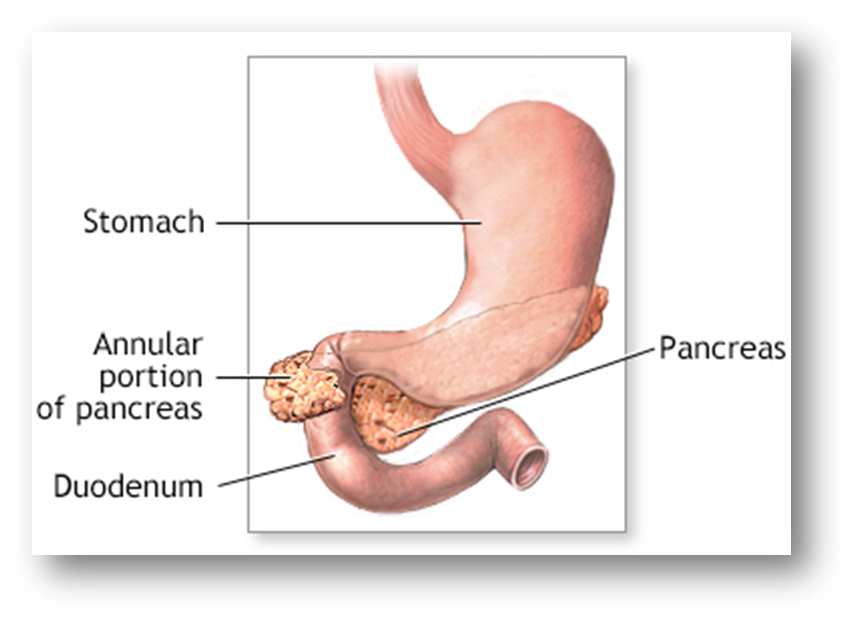

•Annular Pancreas

Rare congenital abnormality

a ring of pancreatic tissue wrapped around duodenum

Associated Down’s syndrome (1 in 4)

Often asymptomatic

Food intolerance, nausea, vomiting, chronic pain

May co-exist with trache-oesophageal fistula

•Pancreatic Rest

Ectopic pancreatic tissue

1-2% autopsy series

Histological variants – ducts, islets, blood supply

can occur throughout GI tract

predominantly gastric & proximal small intestine

Usually asymptomatic

may cause dyspepsia, pancreatitis, mimic tumours

outline the arterial blood supply of the pancreas

•Head supplied by the pancreaticoduodenal arcade arising from GDA and SMA

•Tail supplied by dorsal pancreatic artery medially , caudal and magna that arise from the splenic artery

outline the blood drainage of the pancreas

•Body and tail drains into the splenic vein

•Head and uncinate of pancreas drains into the Superior mesenteric vein and portal vein

Which targeted therapy inhibits hypoxia inducible genes?

sunitinib

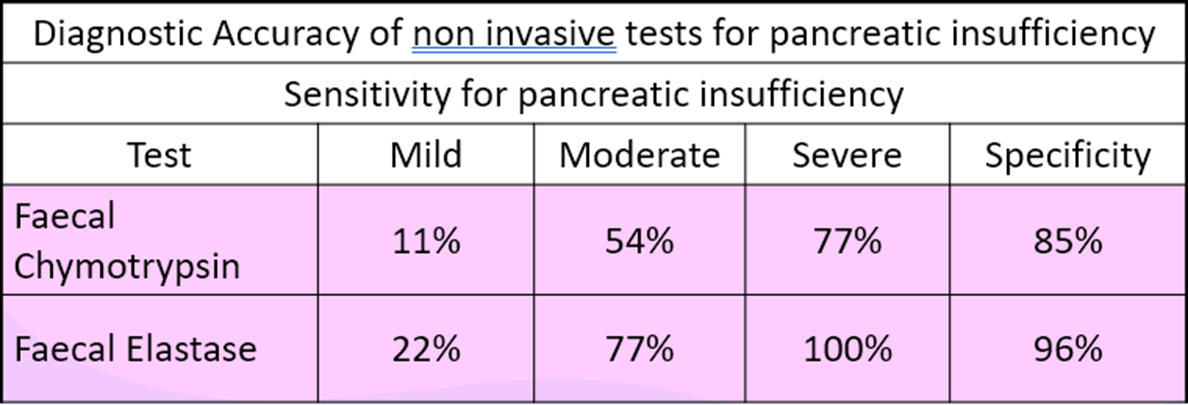

Which tests can indirectly assesses pancreatic function? what’s their diagnostic accuracy?

72 hr faecal fat excretion

Faecal Elastase/Chymotrypsin

Faecal Elastase

-Marker of choice to detect pancreatic insufficiency.

-Endopeptidase and sterol binding protein.

-It is not degraded during transit through the intestinal tract and is stable in vitro.

-< 200 μg/g of stool indicates an exocrine insufficiency.

-Good discrimination between diarrhoea of pancreatic & non-pancreatic origins

-May be useful in determining the amount of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy required in cystic fibrosis or chronic pancreatic insufficiency.

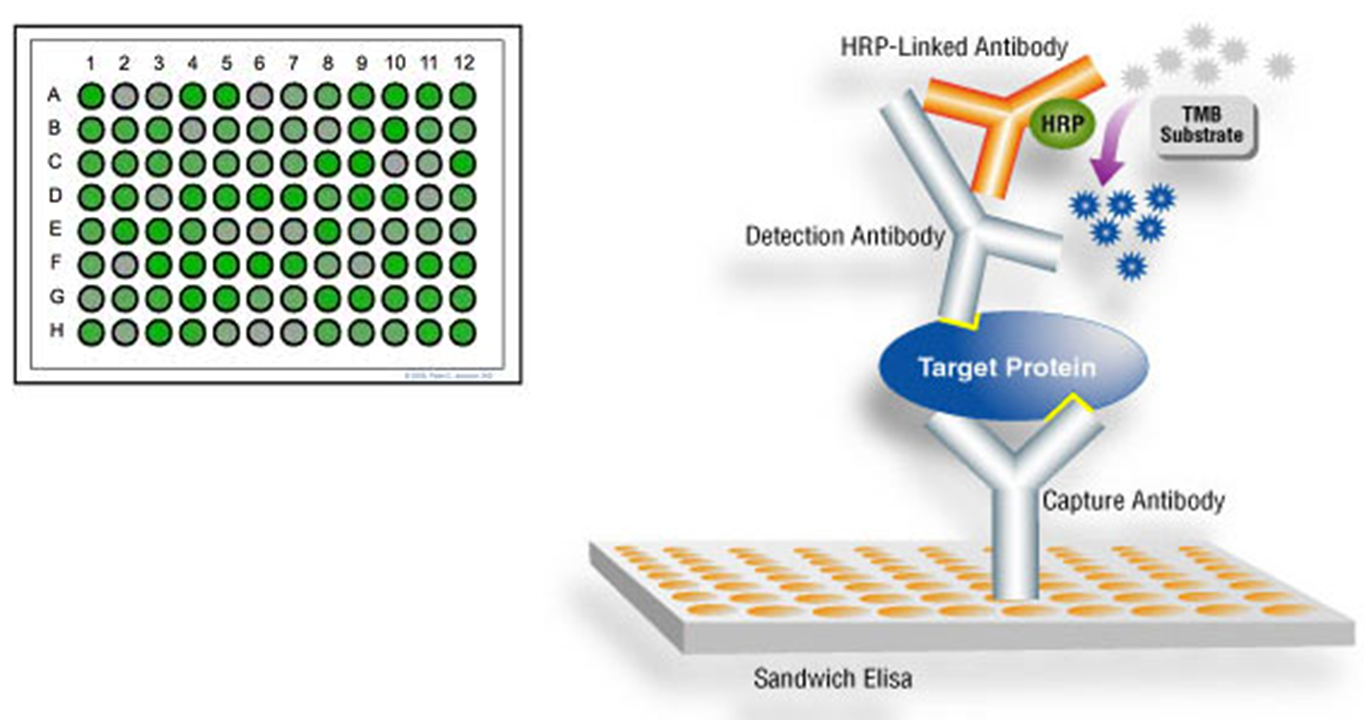

-Measured by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

•Faecal chymotrypsin

–Faecal test for proteolytic enzymes.

–Produced in an inactive form in the pancreas and then activated in the small intestine to digest food proteins.

–Low values indicate pancreatic insufficiency.

–Lack of standardisation in techniques used so difficult to compare results between labs.

Which tests can directly assesses pancreatic function?

At which point in the evolution of abdominal findings for lower GI inflammation would the patient present with involuntary guarding?

transmural inflammation

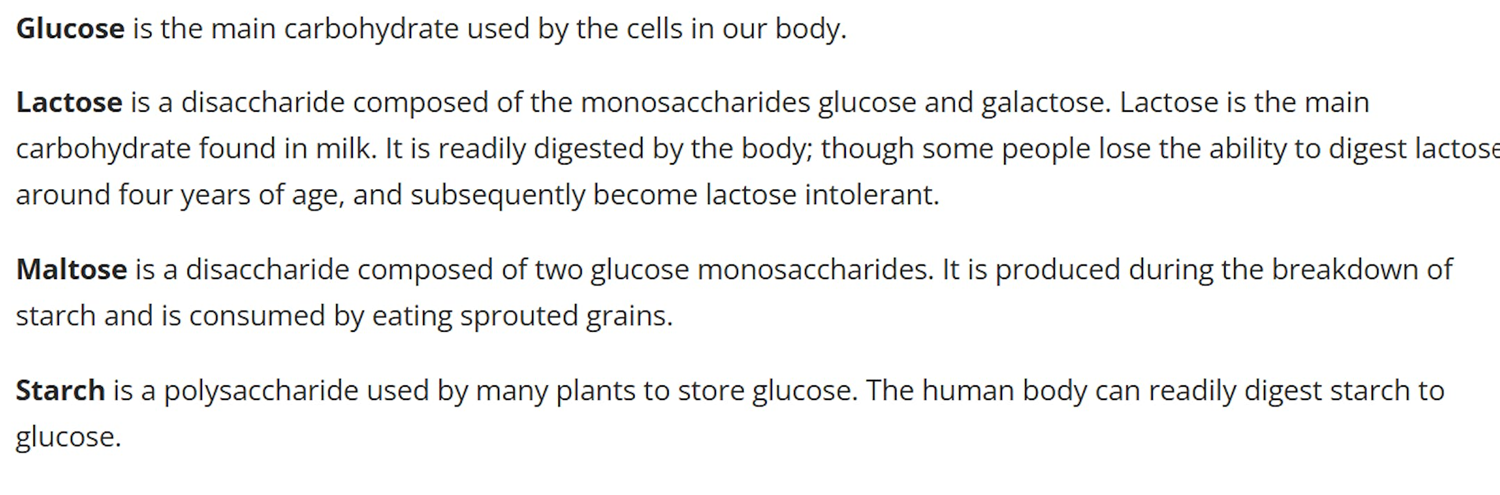

outline different types of carbohydrates

outline the Exocrine pancreatic function

•Central role in digestion & absorption of carbohydrates, fats and proteins.

•Production of bicarbonate and enzymes, including amylase, lipase, trypsin, chymotrypsin, esterases.

•Disorders associated with GI symptoms of malabsorption including diarrhoea & weight loss.

•Acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis and carcinoma of the pancreas.

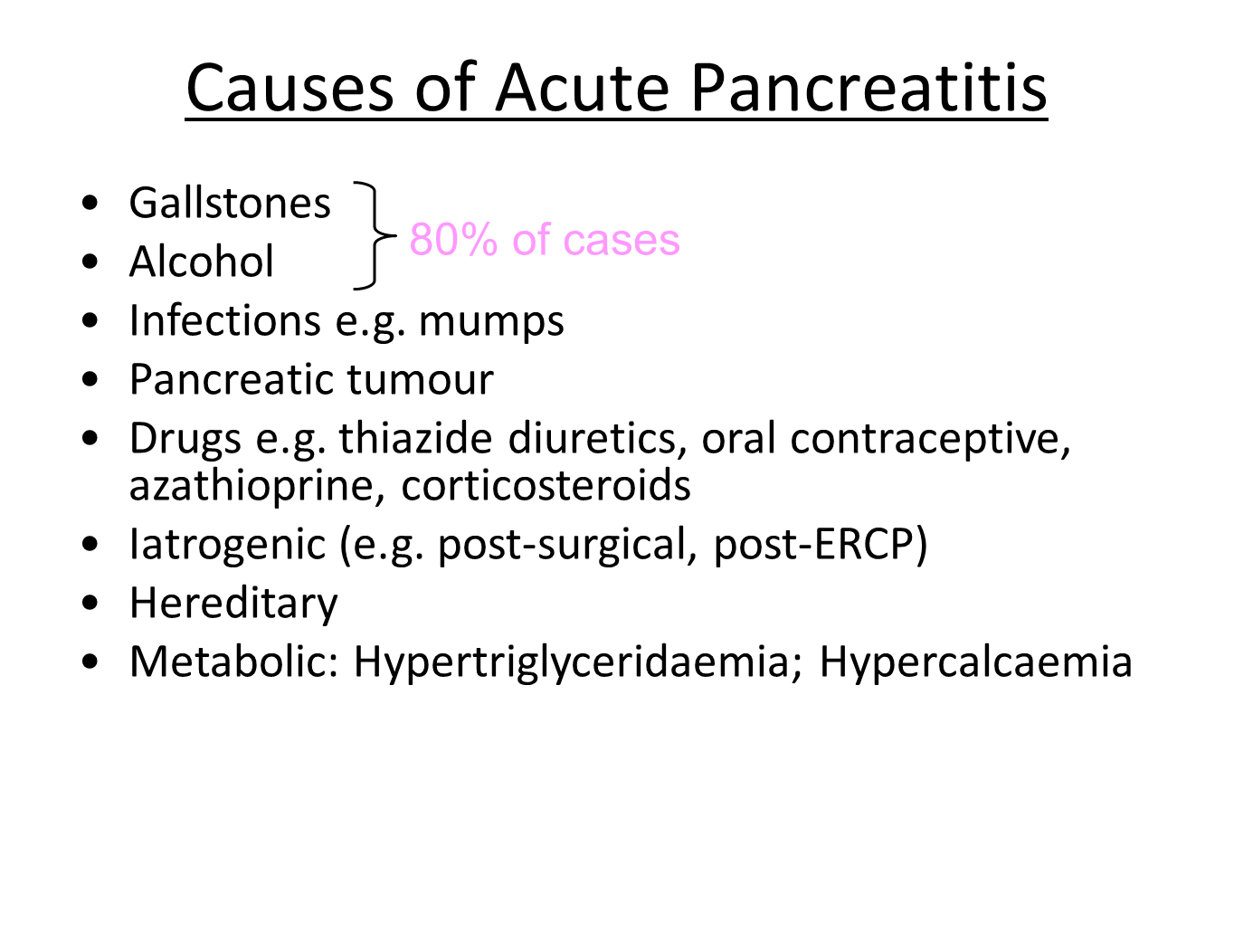

explain the causes of acute pancreatitis

•Acute inflammation of pancreas.

•Common cause of acute abdominal pain.

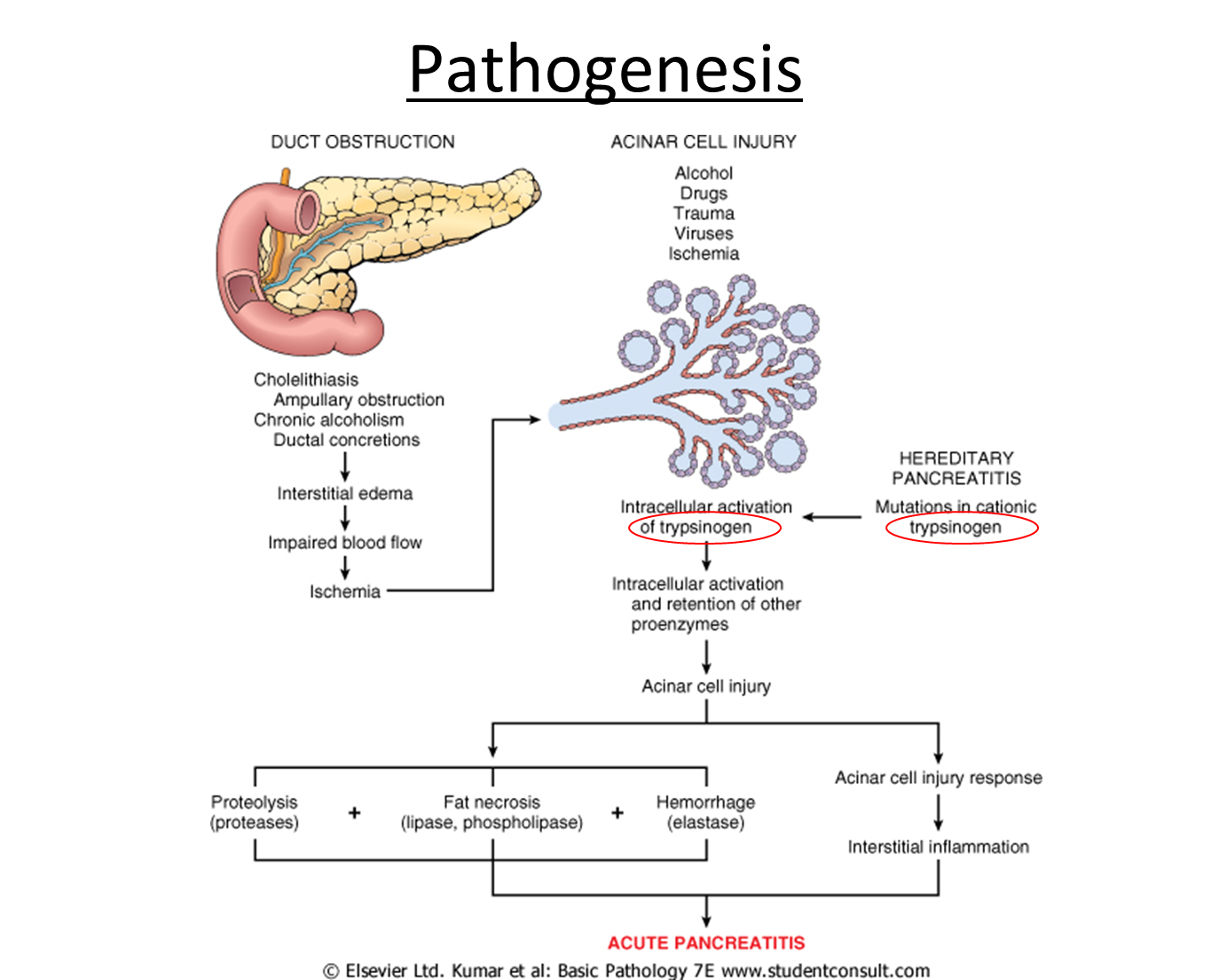

explain the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis

outline the clinical features for acute pancreatitis

•Acute upper abdominal pain, may radiate to back.

•Nausea and vomiting.

•Upper abdominal tenderness/ guarding.

•Severe cases: hypotension, shock, oliguria, & multi-organ failure.

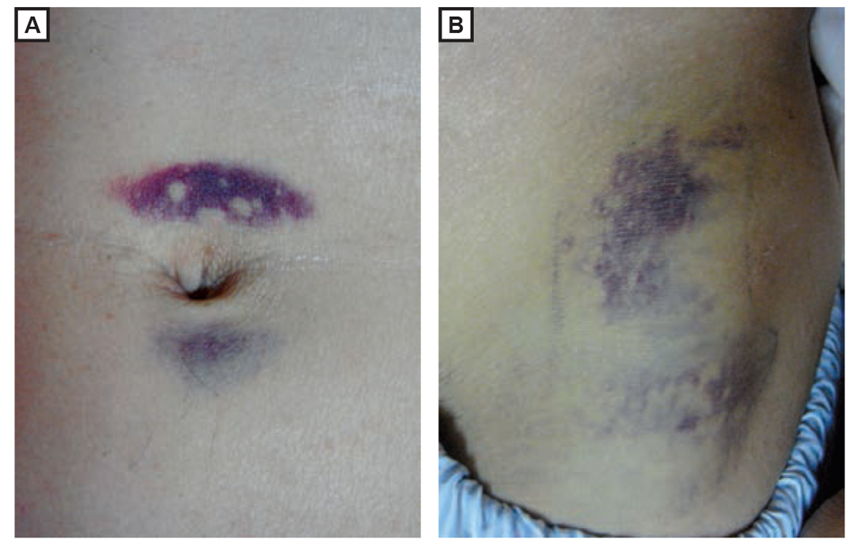

Signs suggesting severe necrotising pancreatitis:

(A) Periumbilical bruising (Cullen sign) (B) flank bruising (Grey Turner sign)

outline the investigations for acute pancreatitis

•Blood & urine tests:

•↑ serum amylase

•↑ serum lipase (less readily available)

•Urinary amylase with ↑ amylase to creatinine clearance ratio

•CRP (severity marker)

•↑urea, ↓albumin, ↓calcium, ↑glucose, ↓P02, ↑transaminases, metabolic acidosis

Imaging

•Erect Chest X-ray – to exclude intra-abdominal perforation.

•Abdominal Ultrasound – screen for gallstones, biliary dilation, detect pancreatic swelling/ necrosis.

•CT abdomen with contrast – image pancreas, look for complications e.g. necrosis, fluid collections, abscesses, pseudocysts.

•MRCP – assess pancreatic damage & look for gallstones.

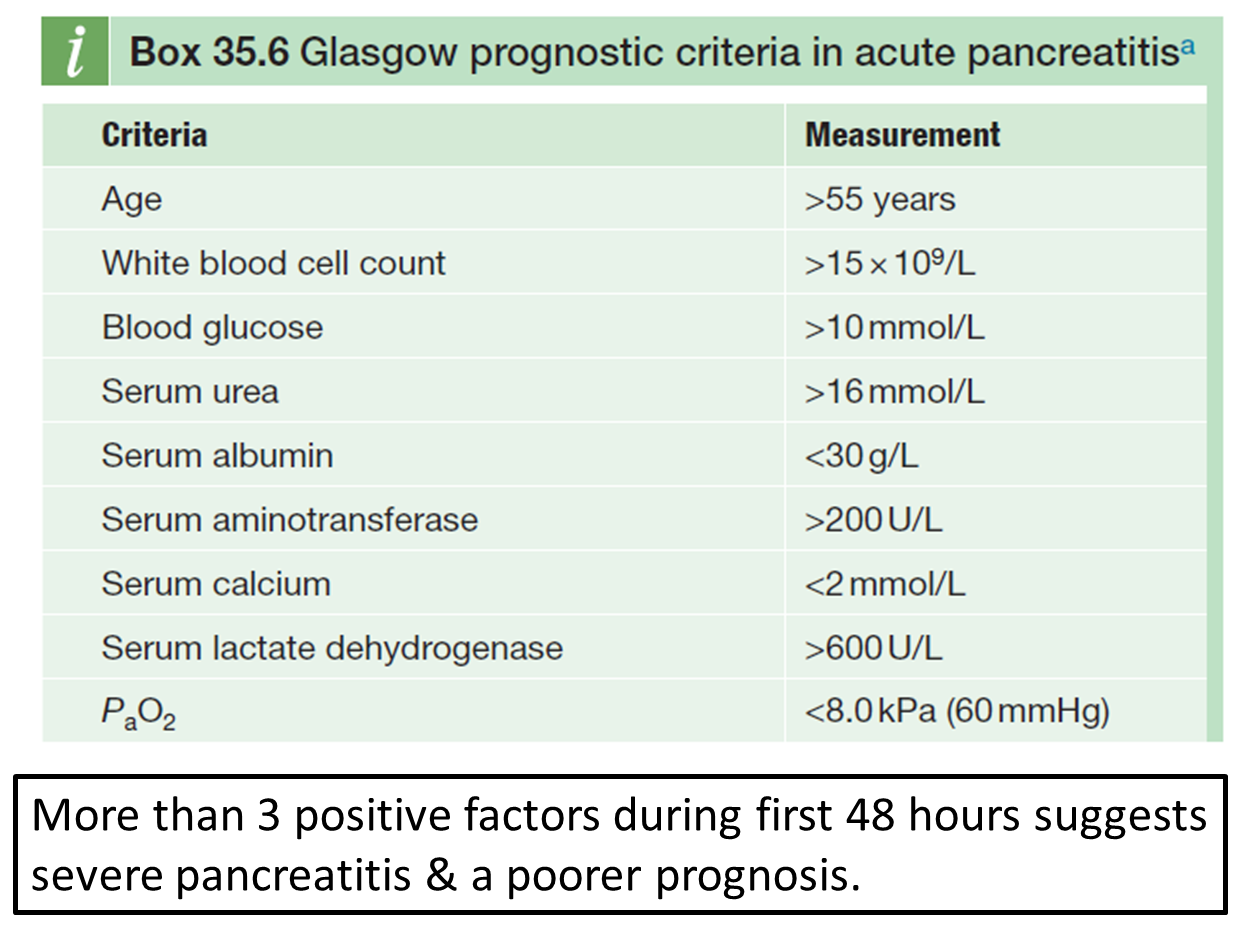

how is disease severity assessed for acute pancreatitis?

outline the management for acute pancreatitis

•Supportive

•IV fluids – can get large fluid losses

•Nasogastric (NG) suction – prevents abdominal distension & vomitus (& risk of aspiration pneumonia)

•Analgesia

•Feeding – NG or NJ (nasojejunal) tube

•Anticoagulate – DVT prophylaxis

•In severe cases, ICU support.

•ERCP – in some cases of gallstone related pancreatitis to remove bile duct stones.

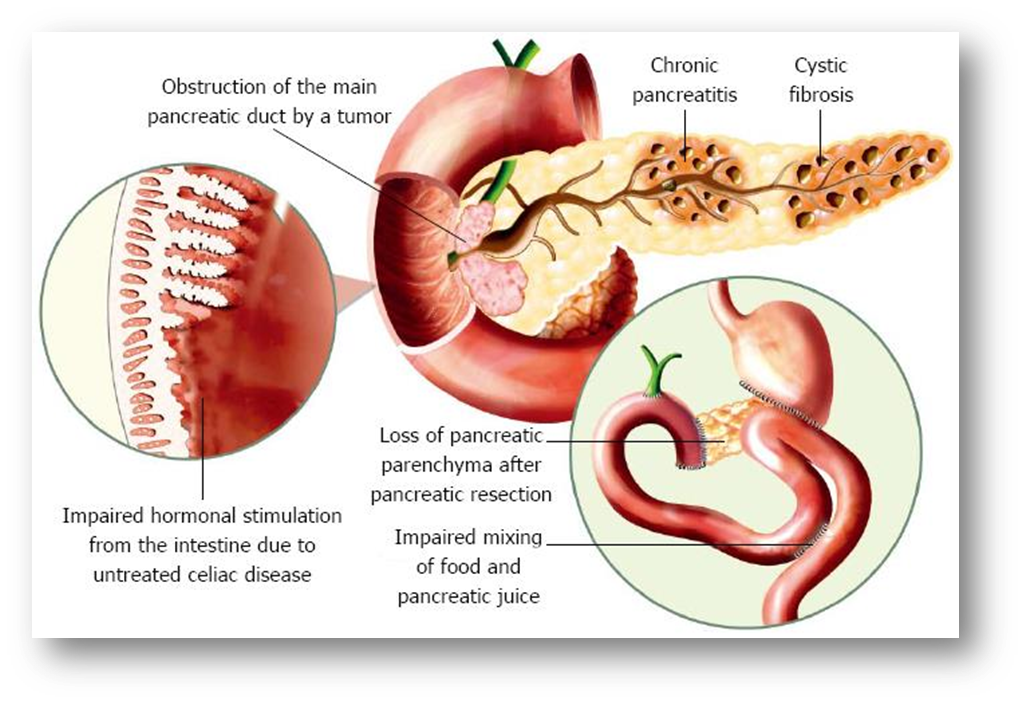

outline chronic pancreatitis and its causes

•Irreversible pancreatic damage leading to destruction of both endocrine and exocrine function.

•Alcohol accounts for 60-80% of cases in developed countries.

•May be secondary to repeated attacks of acute pancreatitis.

causes:

•Alcohol

•Recurrent acute pancreatitis

•CKD

•Hereditary – e.g. Cystic Fibrosis

•Tropical chronic pancreatitis

•Obstructive

•Trauma

•Idiopathic

•Hypercalcaemia

•Autoimmune (IgG4)

explain the pathogenesis of chronic pancreatitis

•↑activated trypsin within pancreas – common pathway to develop chronic pancreatitis.

•May be due to premature activation of trypsinogen to trypsin, or impaired inactivation/ clearance of activated enzyme from the pancreas.

•Protein plugs precipitate in duct lumen and form focus for calcification & cause ductal obstruction, ductal hypertension, & further pancreatic damage.

•Likely also genetic factors contribute (e.g. mutations in PRSS1 gene in hereditary pancreatitis)

outline the clinical features of chronic pancreatitis

•Recurrent abdominal (epigastric) pain radiating to the back.

•Exocrine insufficiency: weight loss & steatorrhoea due to malabsorption.

•Diabetes mellitus due to loss of islet cells (late event)

•Jaundice – obstruction of CBD during its course through fibrosed pancreatic head.

•Approx. 90% of acinar tissue has to be lost before symptoms of malabsorption are seen.

outline the investigations for chronic pancreatitis

•↓Faecal elastase – moderate to severe disease

•Serum amylase & lipase – may be ↑ (not always)

•Abdominal ultrasound

•CT abdomen with contrast – pancreatic calcification & dilated pancreatic duct.

•MRCP (Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography)

outline the management for chronic pancreatitis

•Long-term abstinence from alcohol

•Smoking cessation

•Analgesia – to treat abdominal pain

•Pancreatic enzyme supplements – to treat malabsorption.

•Diabetes – insulin

•Autoimmune cases – prednisolone

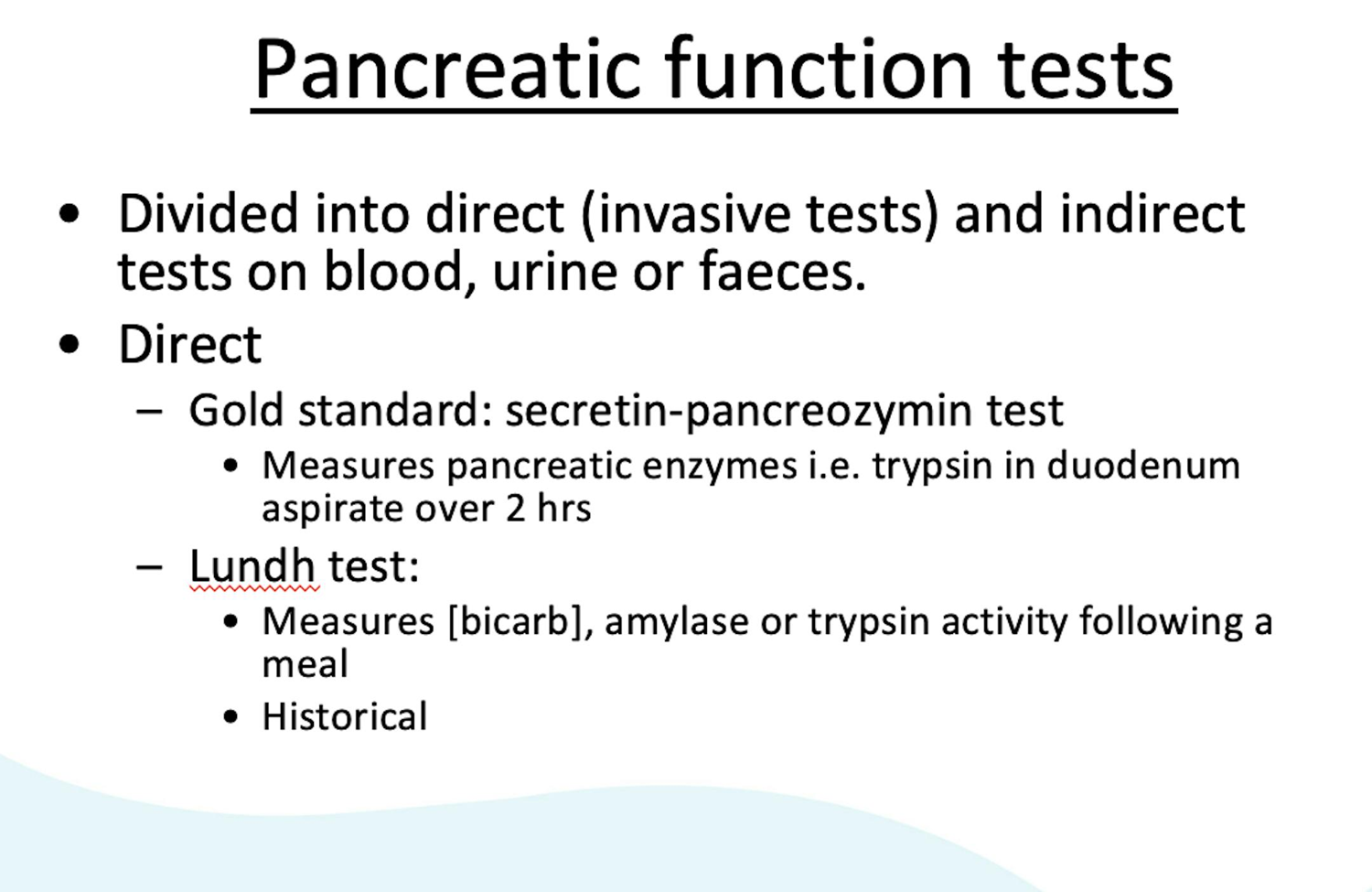

describe the pancreatic tests used

•Tests of pancreatic damage

–Serum amylase

–Urine amylase

–Serum lipase

•Tests of pancreatic function

–Direct (invasive): secretin–pancreozymin test

–Indirect: Faecal elastase

describe α-Amylase and serum amylase

α-Amylase

•Enzyme that hydrolyses alpha bonds of large, alpha-linked polysaccharides such as starch to yield maltose.

•Small enough to pass through glomerulus to urine.

•Present in a number of organs and tissues.

–Salivary glands (S-type), Pancreas (P-type), testes, fallopian tubes, lung etc.

–Different isoenzymes.

•Blood amylase is low and constant.

–Greatly increases in acute pancreatitis or salivary gland inflammation.

describe serum amylase and the causes of hyperamylasaemia (condition of high serum (blood) amylase)

Serum Amylase (blood test that measures the level of the enzyme amylase)

•Serum amylase in acute pancreatitis:

–Rises within 5-8 hrs of onset of symptoms, normalises by day 4.

–Can ↑ by 4-6 times ULN – (normal <100 U/L).

•Low specificity – several other reasons for elevated blood amylase levels (hyperamylasaemia)

CAUSES:

•Pancreatic disease

•Other intra-abdominal disease e.g. perforated peptic ulcer, small bowel obstruction/ perforation

•Ruptured ectopic pregnancy

•Salivary gland lesion e.g. calculi or mumps

•Renal insufficiency

•Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA)

•Tumours e.g. certain lung and ovarian tumours

•Drugs e.g. opiates

•Macroamylase: complex between immunoglobulin and amylase – too large to be filtered through the kidney, so impaired renal clearance, & increased blood amylase levels in absence of disease.

describe urine amylase

[Serum amylase rises quickly in acute pancreatitis, while urine amylase levels rise later and stay elevated longer, making it useful for delayed diagnosis or monitoring. Urinary amylase is also more helpful in cases with normal serum levels, such as with macroamylasemia, where it can help confirm pancreatitis]

•Urine amylase (normal 30-600 U/L)

–Improve diagnostic performance by measuring amylase and creatinine in paired serum and urine samples

•Amylase Clearance/Creatinine Clearance Ratio (ACCR)

ACCR (%) = Urine Amylase (U/L) x Serum Creatinine (µmol/L) x 100

Serum Amylase (U/L) Urine Creatinine (µmol/L)

–Normal ACCR 2-5%; 6-13% in acute pancreatitis.

–Can help exclude macroamylasaemia: ↑serum amylase, ↓urine amylase, ACCR <2%

Amylase isoenzymes: differentiate between S and P

describe serum lipase

•Main enzyme that breaks down dietary fats, triglyceride to monoglycerides and two fatty acids.

•Serum lipase in acute pancreatitis:

–Rises within 4-8 hrs of onset of symptoms, peaks at 24 hrs and normalises within 8-14 days.

–≥3 x ULN (reference range 8-78 U/L).

•Higher clinical sensitivity and specificity than amylase.

outline ELISA

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the quantitative determination of human pancreatic elastase in feces as an aid in the diagnosis of the exocrine pancreatic function.

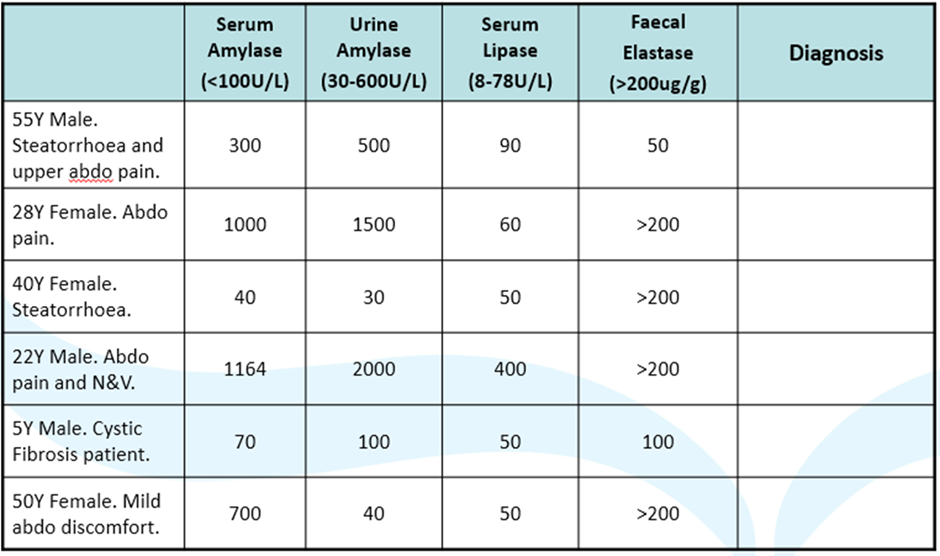

diagnose these clinical scenarios:

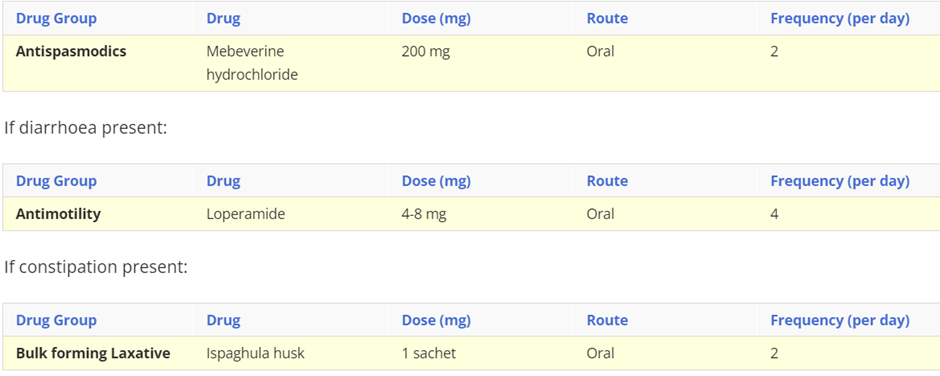

describe irritable bowel Syndrome, include symptoms, cause and treatment (drug class, drug name, route, frequency)

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common, chronic, relapsing, and often life-long condition, mainly affecting people aged between 20 and 30 years. It is more common in women.

Symptoms: Abdominal pain or discomfort, disordered defaecation (either diarrhoea, or constipation with straining, urgency, and incomplete evacuation), passage of mucus, and bloating. Symptoms are usually relieved by defaecation.

Causes: The exact cause is unknown, but has been linked to food passing through your gut too quickly or too slowly, oversensitive nerves in your gut, stress and a family history of IBS.

Treatment:

In addition to dietary and lifestyle advice, decisions about pharmacological management should be based on the nature and severity of symptoms.

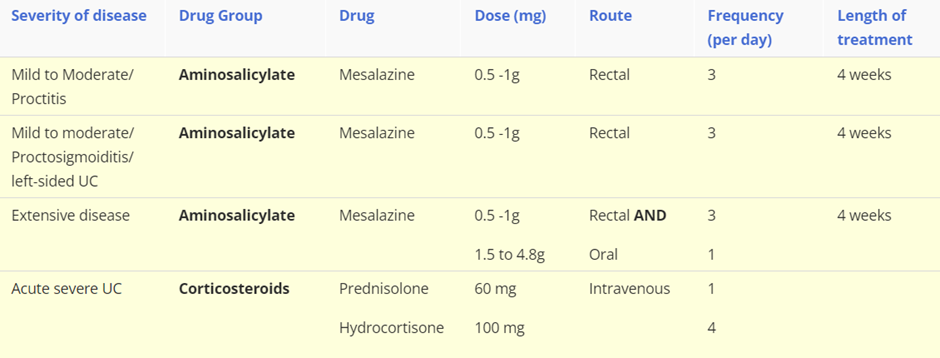

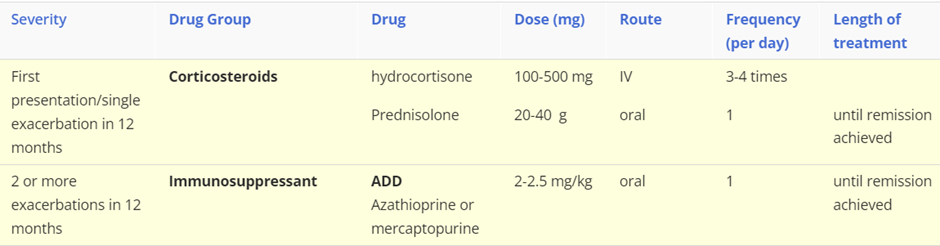

describe ulcerative colitis, include symptoms, cause and treatment (severity of disease: drug class, drug name, route, frequency)

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory condition of the colon and rectum. It characterised by diffuse mucosal inflammation, which has a relapsing-remitting pattern. It is a life-long disease that is associated with significant morbidity. It most commonly presents between the ages of 15 and 25 years, although diagnosis can be made at any age. Complications associated with ulcerative colitis include an increased risk of colorectal cancer, secondary osteoporosis, venous thromboembolism, and toxic megacolon.

Symptoms: Recurring diarrhoea, which may contain blood, mucus or pus, abdominal pain and an urgent need to defaecate.

Causes: Unknown although it’s thought to result from a problem with the immune system.

Treatment: First-line treatments

NB/ These are first line treatments and if remission is not achieved, or the patient can not tolerate/declines treatment then alternative therapies are required. For example with acute severe ulcerative colitis, which requires hospitalisation, these are the following steps in drug choice:

Step 1: Corticosteroid

Step 2: Ciclosporin

Step 3: infliximab

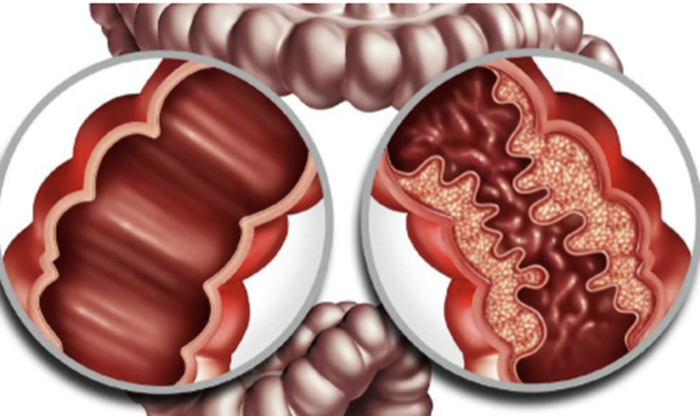

describe Crohn’s disease, include symptoms, cause and treatment (severity of disease: drug class, drug name, route, frequency)

Crohn's disease is a chronic, inflammatory bowel disease that mainly affects the gastro-intestinal tract. It is characterised by thickened areas of the gastro-intestinal wall with inflammation extending through all layers, deep ulceration and fissuring of the mucosa, and the presence of granulomas; affected areas may occur in any part of the gastro-intestinal tract, interspersed with areas of relatively normal tissue. Crohn's disease may present as recurrent attacks, with acute exacerbations combined with periods of remission or less active disease.

Gastrointestinal wall demonstrates a prominent cobblestone appearance.

Symptoms: May include abdominal pain, diarrhoea, fever, weight loss and rectal bleeding, but are dependent on the site of the disease.

Causes: Unknown however there is a genetic link so you're more likely to get it if a family member has it. It may arise from problems with the immune system leading it to attach the digestive system. Other causes include smoking, previous stomach bug and abnormal balance of gut bacteria.

Treatment:

describe the different Gastrointestinal infections, include symptoms, cause and treatment (severity of disease: drug class, drug name, route, frequency) for each

Gastrointestinal infections include:

Gastro-enteritis: transient disorder due to enteric (small intestine) infection which leads to inflammation of the GI tract. It is usually caused by viruses, however bacteria, parasites and fungi can causes gastroenteritis. Symptoms include a sudden onset of diarrhoea, with or without vomiting. Frequently self-limiting and not bacterial therefore antibiotics are not usually indicated.

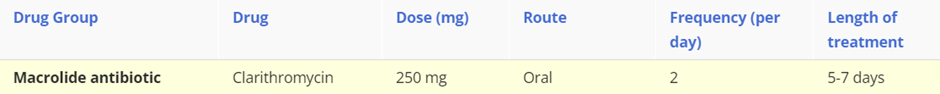

Campylobacter enteritis: Campylobacter is one of the commonest bacterial food borne infections in the UK, which is transmitted by contaminated food such as poultry, milk or water. It can lead to inflammation, ulceration and bleeding in the small and large bowel leading to bloody diarrhoea, cramping, abdominal pain & fever.

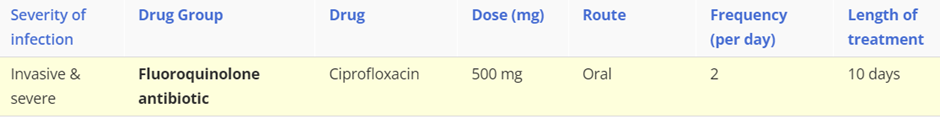

Salmonella: is an infection with Salmonella bacteria and is one of the most common causes of food poising or gastroenteritis. Salmonellae ingested in food survive passage through the gastric acid barrier and invade the mucosa of the small and large intestine and produce toxins. Invasion of epithelial cells stimulates the release of proinflammatory cytokines which induce an inflammatory reaction. The acute inflammatory response causes diarrhoea and may lead to ulceration and destruction of the mucosa. The bacteria can disseminate from the intestines to cause systemic disease. Typical symptoms include diarrhoea, stomach cramps, nausea, vomiting and fever.

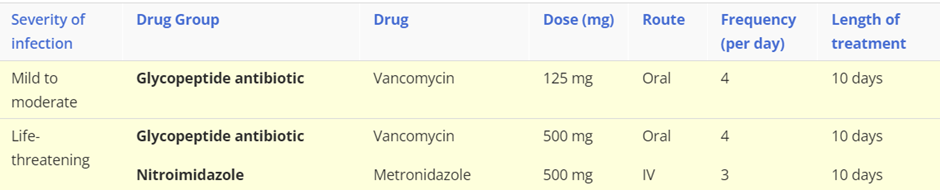

Clostridium difficile: an infection caused by the growth of the causative bacterium and release of its toxins into the gastrointestinal tract. The bacterial toxin causes inflammation of the large bowel known as pseudomembranous colitis. Symptoms include watery diarrhoea, which can be bloody, stomach cramps, nausea, fever, signs of dehydration with loss of appetite and weight.

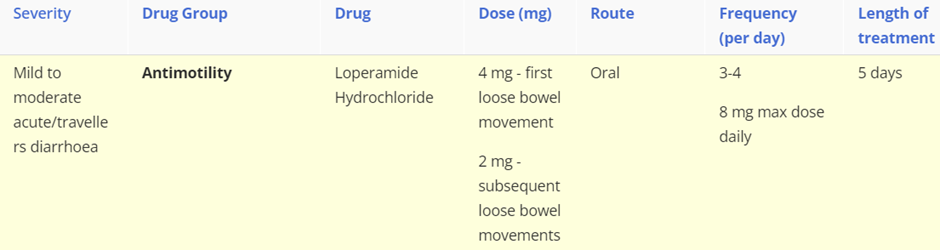

describe diarrhoea and constipation, include symptoms, types (for diarrhoea) causes and treatment (severity of disease: drug class, drug name, route, frequency)

Diarrhoea

Diarrhoea is the passage of three or more loose or liquid stools per day (or more frequently than is normal for the individual).

Acute diarrhoea is defined as lasting less than 14 days. It is usually caused by a bacterial or viral infection.

Persistent diarrhoea is defined as lasting more than 14 days.

Chronic diarrhoea is defined as lasting for more than 4 weeks. It is usually caused by IBS, diet, inflammatory bowel disease, coeliac disease and bowel cancer.

Treatment: Most episodes of acute diarrhoea will settle spontaneously without medical treatment. Oral rehydration therapy is initially used to prevent or correct dehydration diarrhoea. However, when rapid control of symptoms are required then the following can be administered.

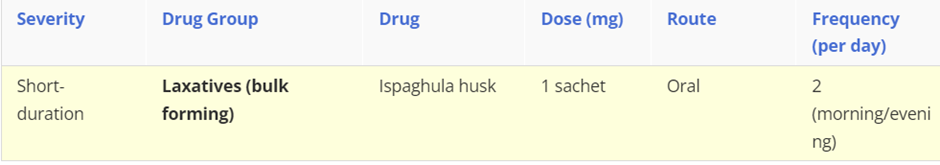

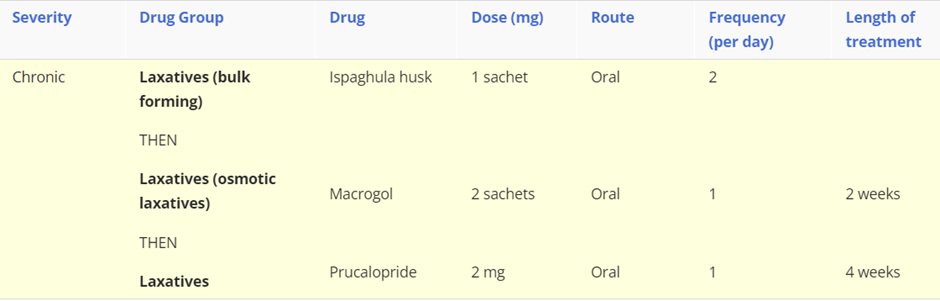

Constipation

Constipation is a heterogeneous symptom-based disorder which describes defecation that is unsatisfactory because of infrequent stools, difficulty passing stools, or the sensation of incomplete emptying. It can occur at any age but is more common in women, the elderly and during pregnancy. Social factors include low fibre diet or low calorie intake, difficult access to toilets, lack of exercise and genetic factors. Psychological causes anxiety or depression as well as eating disorders.

For chronic constipation a bulk forming laxative should be initiated, however if the patient doesn’t respond then switch to an osmotic laxative, such as Macrogol. If at least two laxatives have been tried for at least 6 months then prucalopride (in women only) can be considered.

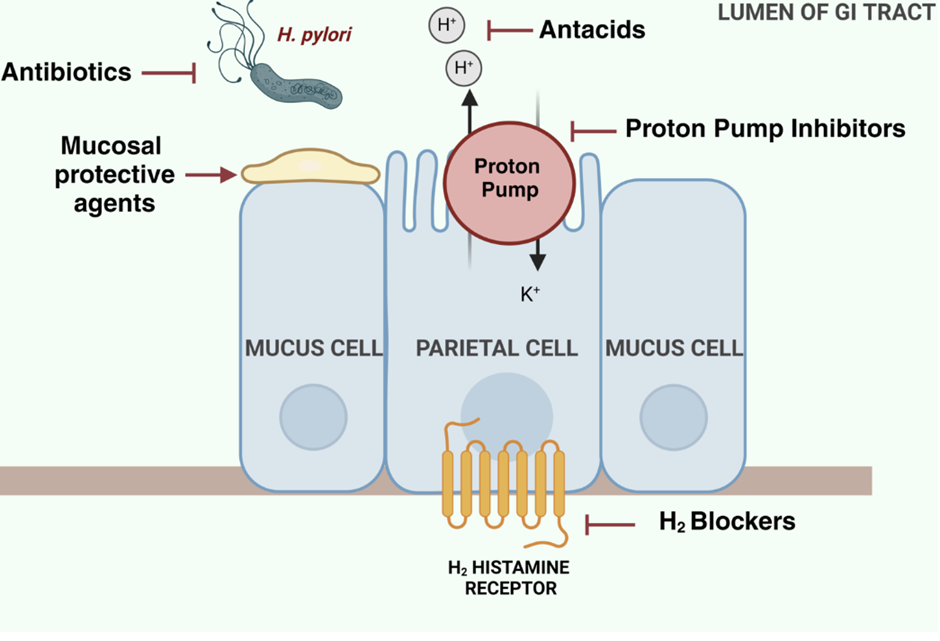

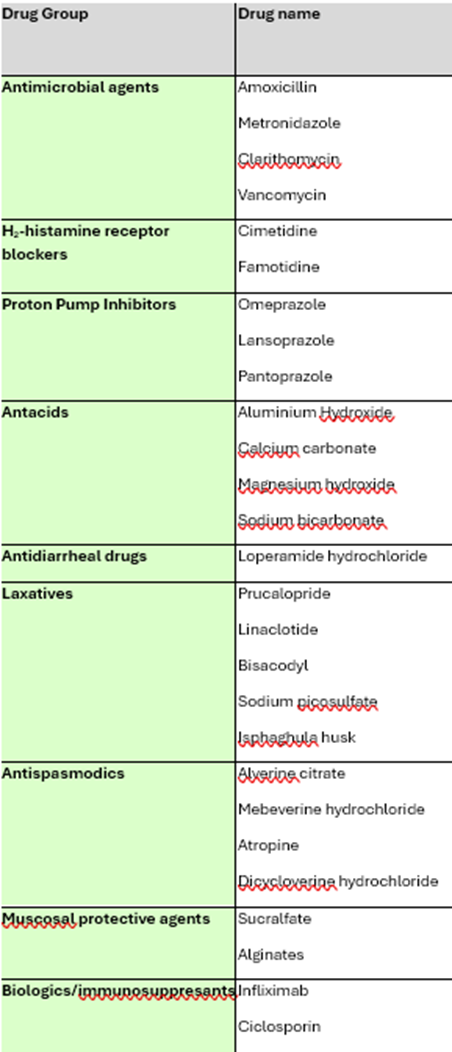

understand where GI drugs work, including Antimicrobial agents (eg. antibiotics), antacids, PPIs, mucosal protective agents, H2 blockers and give examples for each, focusing on the GI drugs.

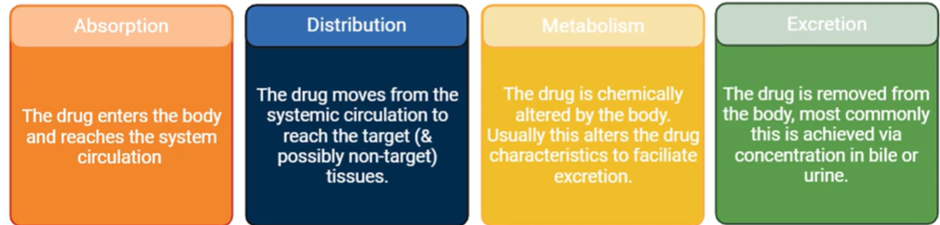

what are The four aspects of pharmacokinetics

The four aspects of pharmacokinetics are absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME)

explain the term pharmacokinetics

"What the body does to the drug" following administration, and refers to the movement of a drug into, through, and out of the body.

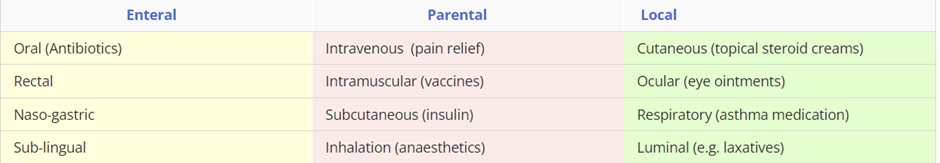

describe the different routes of drug delivery and when they are most suitable

Administration routes can be classified based on where their target of action is. These administration routes can be:

Enteral: delivery of the drug via the GI tract with a system-wide effect.

Parenteral: delivery of the drug that bypass the GI tract and have a system-wide effect.

Local: deliver drugs to specific tissues with a local effect.

There are multiple routes of drug administration, however most drugs are administered orally, because it is the simplest and most convenient route. An alternative administration route is considered when:

a drug is digested/absorbed poorly so only a small amount reaches the blood circulation

rapid onset of action is required

a drug irritates the stomach lining inducing vomiting or diarrhoea.

how is the appropriate route for drug administration chosen?

The route must provide adequate and reliable delivery of the drug.

It must be acceptable for the patient.

It should minimise adverse drug effects.

Ideally it should be self-administered, however some routes do require specialist training and equipment therefore can only be administered by a health professional.

understand the advantages and disadvantages of each route of administration

Route of administration | Advantage | Disadvantages

|

Oral | Self-administration Suitable for prolonged administration Route convenient, safe & economical | Vulnerable to first-pass metabolism/stomach enzymes/gut contents & motility Unpredictable absorption Delayed onset of action |

Intravenous | Direct access to systemic circulation Bypasses first-pass metabolism Predictable blood concentration Rapid onset of action | Vulnerable to overdose & infection/local venous thrombosis Unsuitable for prolonged administration |

Inhalation | Self-administration Suitable for prolonged administration Rapid absorption Bypasses first-pass metabolism | Apparatus required for administration Patient technique can be ineffective |

Intramuscular | Route reliable Bypasses first-pass metabolism Suitable for prolonged administration Slower onset of action (to IV) | Unpredictable/incomplete absorption Limited injection volume |

Rectal | Bypasses first-pass metabolism | Patient embarrassment Rectal inflammation with repeated doses Absorption unreliable |

Subcutaneous | Self-administration Route reliable Complete absorption Slower onset of action (to IV) | Painful, tissue damage Limited injection volume |

Topical | Self-administration Route convenient High concentration locally, avoiding systemic side effects | Absorption can occur if tissue damaged |

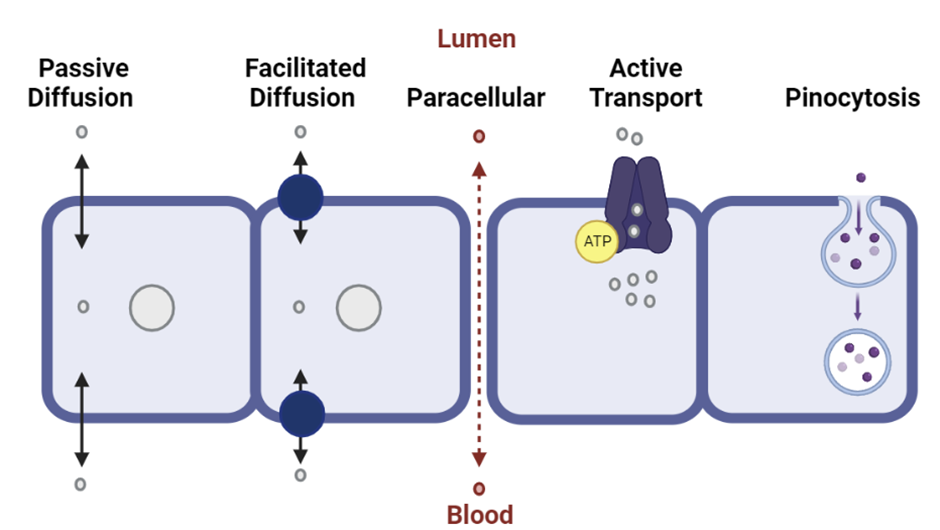

describe drug absorption

Drugs must pass from the site of administration in to the bloodstream through a process known as absorption.

With the exception of IV administration, drug molecules must cross cell membranes to enter the blood circulation. Drugs can travel between cells (paracellular) or through cells (transcellular) by penetration of the lipid cell membrane.

Membrane permeation by drugs can occur by the following routes:

what are drug absorption enhancing and reducing systems and factors?

there are specialised transport systems in the small intestine that play a crucial role in enhancing and reducing the intestinal absorption of some drugs.

Both influx and efflux transporters are located on the apical and basal membranes of the intestines.

Influx transporters: belong to the solute carrier (SLC) transporter superfamily that facilitates the absorption of the antibiotic penicillin and the antihypertensive angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. These transporters facilitate the passive movement of solutes down their electrochemical gradient.

Efflux transporters: belong to the adenosine triphosphate binding cassette (ABC) superfamily and limit the absorption of heart failure medication digoxin, and the immunosuppressant cyclosporine. These are active transporters that utilise ATP to pump drugs against their electrochemical gradient.

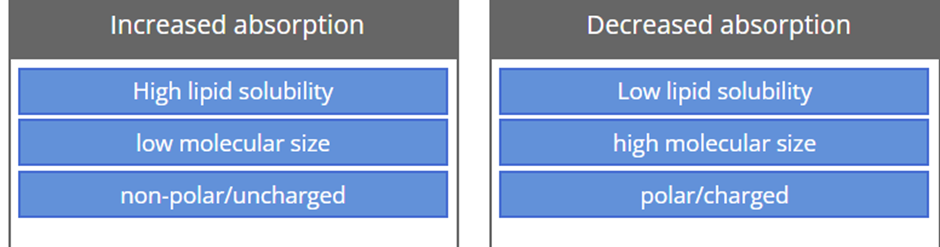

Drug factors affecting the rate & extent of drug absorption include:

Molecular size

Lipid solubility

pKa & pH

Patient factors affecting the rate & extent of drug absorption include:

Age

Disease status (eg. Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis can decrease the functional surface area of the intestines reducing drug absorption.)

Blood flow (splanchnic, increases absorption of drug, which is why some drugs benefit from being taken after a meal)

Gastric acid secretion (Reduced gastric acid secretion increases bioavailability of drugs that are usually degraded in an acid environment and decreases bioavailability of weakly acidic drugs.)

Gastric emptying (increasing the rate of gastric emptying, increases the rate of drug absorption. In contrast, reducing GI emptying slows down drug absorption)

Gastric content (fed vs fasting) (depending on drug)

define first pass metabolism

First-pass metabolism: is a process in which a drug administered by mouth has to pass through three organs: the stomach, intestine and liver. It must avoid inactivation and degradation by stomach acid and digestive enzymes in the GI tract and liver in order to reach the systemic circulation and have a therapeutic effect.

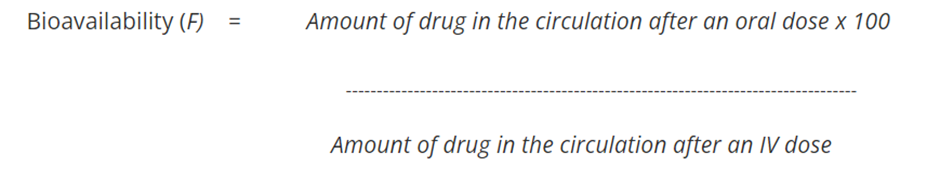

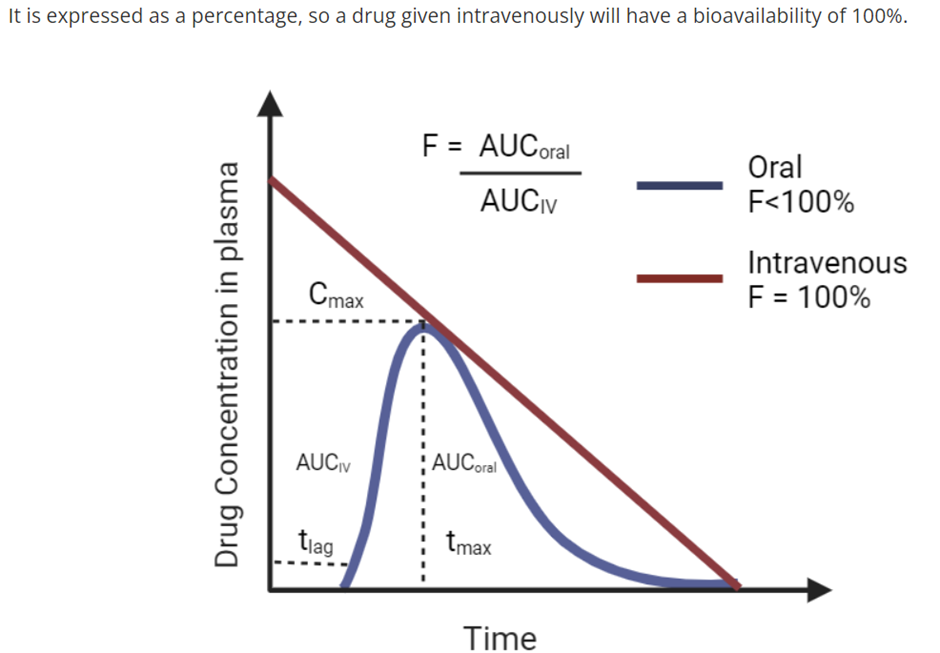

what does the bioavailability of a drug means?

Some drugs will be significantly eliminated before they reach the systemic circulation, either through efflux transporters or metabolism by enteric bacteria in the large intestine, or after delivery by the portal circulation to the liver. Consequently, the dose administered orally is not equal to the amount found in the systemic circulation.

In contrast, intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous and sublingual administration of a drug by-passes these obstacles, therefore the amount administered is normally equivalent to amount found in the blood plasma. This is because the blood supply from these areas does not pass through the liver via the portal circulation, but drains directly in to the systemic circulation. The term used to quantify the amount of drug that reaches the systemic circulation is bioavailability.

how’s the bioavailability of a drug measured?

eg. Question: A patient is administered 20 mg of omeprazole orally and the fraction that reaches the bloodstream intact is 6 mg. If administered intravenously, 100% of the drug would reach the systemic bloodstream. Calculate the bioavailability of orally administered omeprazole?

30%

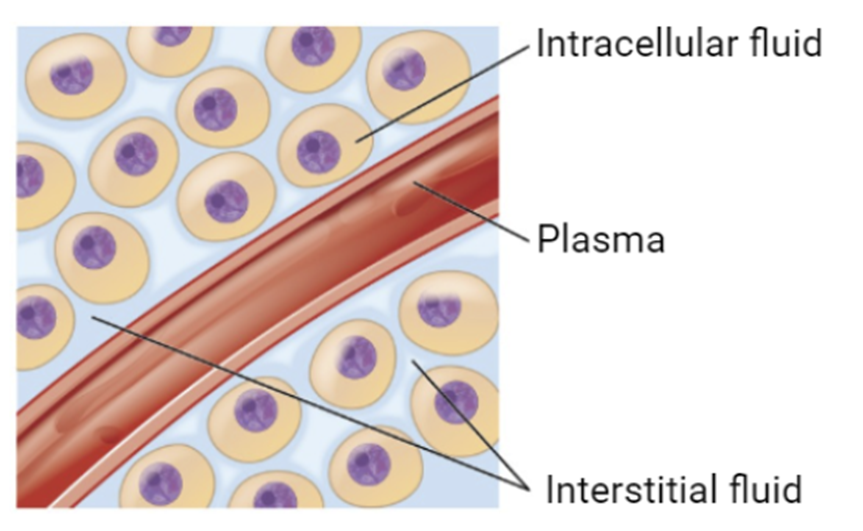

describe drug distribution

In order for a drug to have any therapeutic benefit it must be able to reach the blood circulation so that it can be distributed around the body and reach the intended target site.

Most drugs entering the body DO NOT spread rapidly throughout the whole body of water to achieve a uniform concentration.

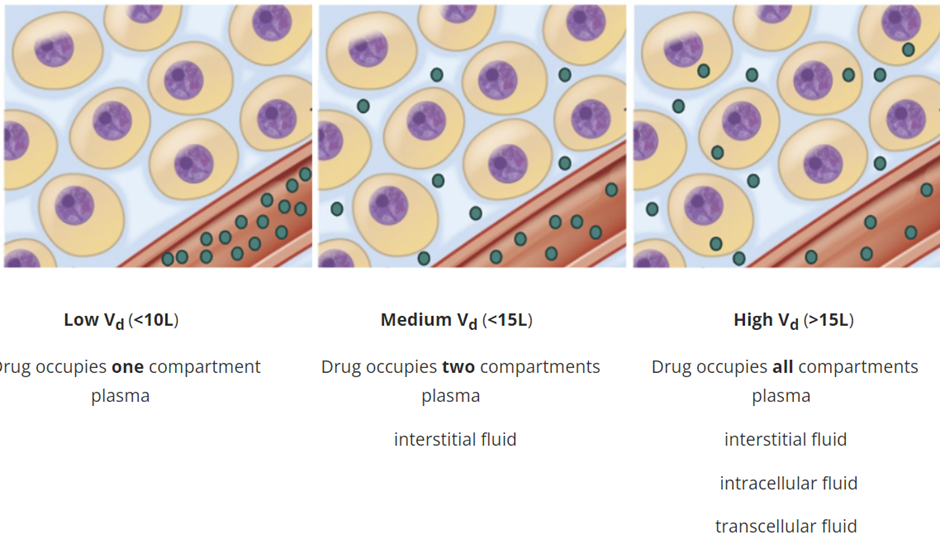

Four major compartments are:

Plasma water (3L)

Interstitial water (11L)

Intracellular water (28L)

Transcellular water (portion of total body water contained within specialized, epithelial-lined spaces, such as the CNS, serous cavities)

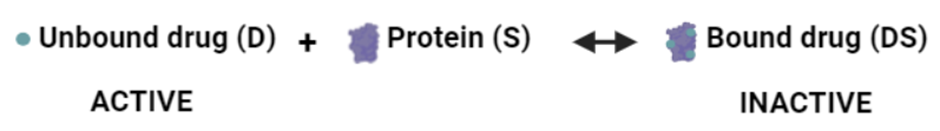

Cell membranes form a barrier between each compartment where a drug exists in equilibrium between a protein-bound or unbound form, however only the unbound drug can move across the cell membrane between compartments and elicit an effect.

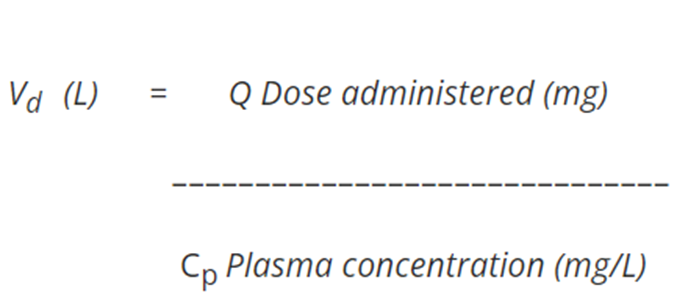

define Volume of Distribution (Vd), how is calculated and why

Volume of Distribution (Vd): is an estimation of drug distribution and can be defined as the volume of plasma that would be necessary to account for the total amount of drug in the patient's body. Vd is a theoretical value and is calculated from the dose administered (Q) relative to the concentration of that drug in the blood plasma (Cp).

Vd is usually further divided by the patient's body weight and expressed in terms of litres/kg (L/Kg).

Estimation of Vd is used clinically to determine the loading dose necessary to achieve a desired blood concentration of drug more quickly than if the maintenance dose was used where clearance might delay the level of drug concentration needed to reach a therapeutic level.

Vd that exceeds body water (42L)=> Drug is also distributed within the tissue and binds extensively to tissue proteins.

Consequently, a drug with a high Vd has a propensity to leave the plasma and enter the extravascular compartments of the body meaning that a higher dose of a drug is required to achieve a given plasma concentration. Conversely, a drug with a low Vd has a propensity to remain in the plasma meaning a lower dose of a drug is required to achieve a given plasma concentration.

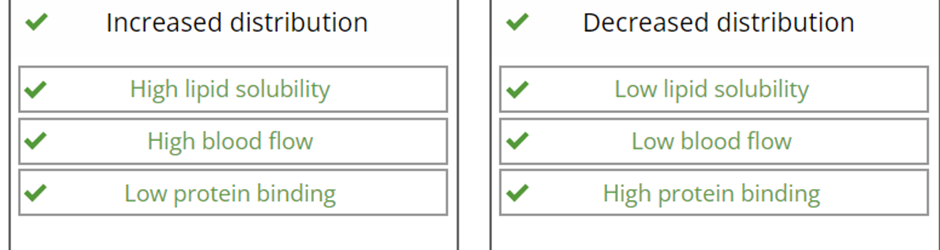

Drug Factors affecting the rate of drug distribution are: Drug-protein binding and Lipid solubility of the drug.

when they are high or low what is their effect on drug distribution?

what are patient factors that affect the rate of drug distribution ?

Kidney & liver function chronic renal/hepatic disease can lead to a reduction in serum albumin, this (Hypoalbuminemia) reduces protein binding of acidic drugs, increasing the free (active) drug fraction, which enhances distribution and potentially toxicity.

Age (higher doses (per kg of body weight) of water-soluble drugs are required in younger children because a higher percentage of their body weight is water. Conversely, lower doses are required to avoid toxicity as children grow older because of the decline in water as a percentage of body weight.)

Obesity (The amount of fat tissue in a person’s body increases the distribution space and thereby lowers the serum concentrations of fat soluble (highly lipophilic) medications)

Dehydration (can reduce the volume of distribution leading to increases in the plasma concentration of water soluble drugs, which can lead to toxicity)

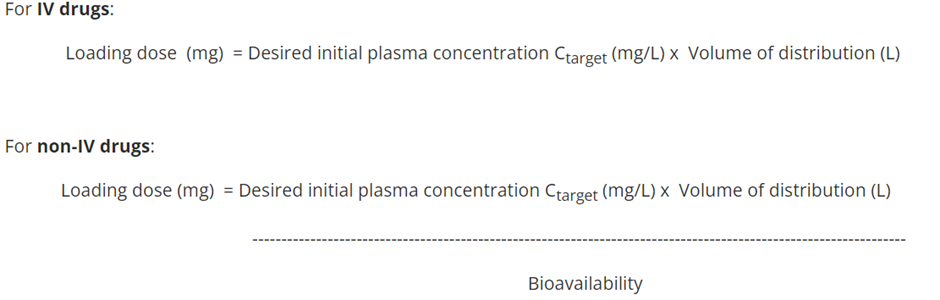

explain Loading dose of a drug, including the calculations for it (IV and non-IV)

Sometimes rapid obtainment of desired plasma levels are needed for serious/life threatening situations. Therefore a loading dose is administered to achieve the desired plasma level rapidly, followed by a maintenance dose to maintain steady state.

Long half-life= it's the time it takes for the plasma concentration of the drug to decrease by 50%. It typically takes 4–5 half-lives to reach steady-state.

A loading dose is most useful for drugs that have a relatively long half-life. Without an initial loading dose these drugs would take a long time to reach a therapeutic range. However disadvantages of loading doses are that there is an increased risk of drug toxicity and a longer time for the plasma concentration to fall if excess levels occur.

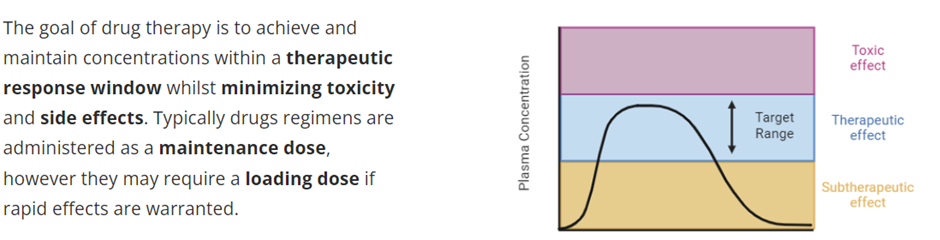

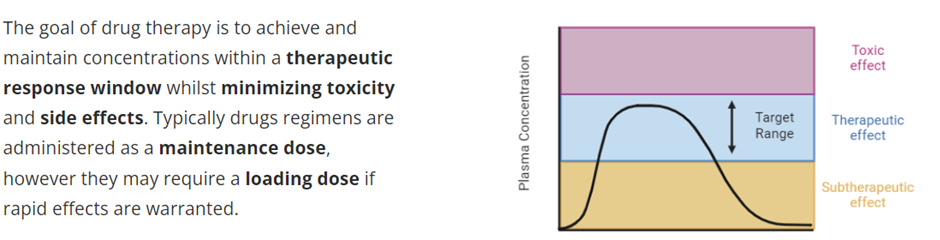

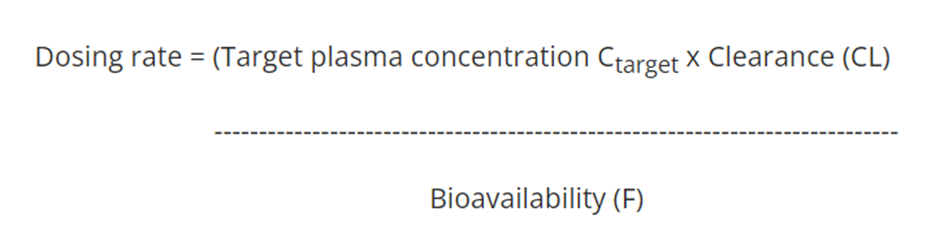

describe the Maintenance Dose of a drug, including the calculation

Maintenance dose

Drugs are generally administered to maintain a steady state concentration within a therapeutic range, which takes 4-5 half lives to achieve. This is dependent on the rate of administration and the rate of elimination of the drug. The dosing rate can be determined by knowing the target concentration in the plasma (Ctarget), clearance of the drug from the systemic circulation (CL) and the bioavailability (F).

explain Dose adjustments and its calculation

Dose adjustments

The amount of drug administered for a given condition is estimated based on an average patient. This approach overlooks variability in pharmacokinetic parameters that can arise due to a number of factors (e.g. genetics, disease). Therefore by understanding pharmacokinetic principles you can adjust the dosage to optimise therapy for a given patient.

To determine dosage adjustments, the plasma concentration (C1) of the drug and the volume of distribution (Vd) can be used to calculate the amount of drug needed to achieve a desired plasma concentration (C2) .

Dose adjustment = Vd (L) x (C2 mg/L - C1 mg/L)

C1 = concentration of drug in the plasma (mg/L)

C2 = desired concentration of drug in the plasma (mg/L)

Vd = volume of distribution (L)

Explain the importance of therapeutic drug monitoring

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

The ability to measure changes in drug concentration over time is of vital importance for clinicians where patient variability in ADME requires dose adjustments to be made for a drug to remain effective and safety concerns manageable. This is known as therapeutic drug monitoring and usually focuses on drug concentrations in the plasma, as these can be readily measured compared to tissue concentrations. The aim is promote optimum drug treatment by maintaining the plasma drug concentration within a therapeutic range for as long as possible while avoiding toxicity.

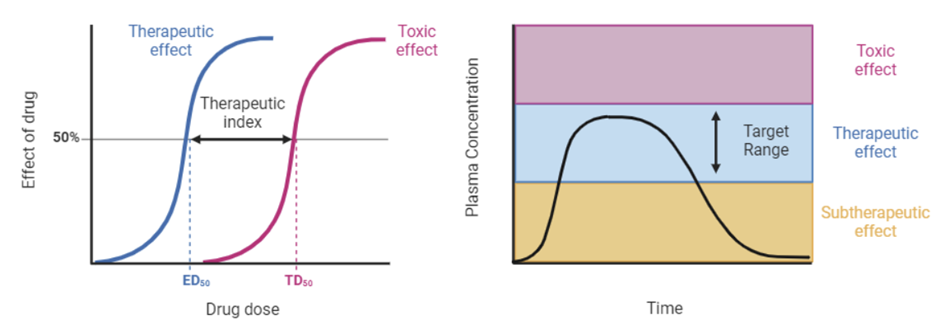

Define therapeutic index and its application to prescribing

Therapeutic Index

Interpreting pharmacokinetic data consists of fitting concentration versus time data and determining parameters that can be used to adjust the dose regimen to achieve a desired target plasma concentration.

Therapeutic index (TI): is a quantitative measurement of the margin of safety that exists between the dose of a drug that produces the desired effect and the dose that produces an unwanted and possible dangerous side effects.

TD50 is the dose required to produce a toxic effect in 50% of the population.

ED50 is the dose required to produce a therapeutic effect in 50% of the population

Therapeutic Index (TI) = TD50

---------------------

ED50

ED50 and TD50 are both calculated from dose-response curves. Higher therapeutic indexes, where the therapeutic dose is much lower than the toxic dose, are preferable because they allow maximal benefit with a minimal risk of side effects. In contrast, a drug with a low therapeutic index, has a very narrow window to have an effect before toxic effects are experienced.

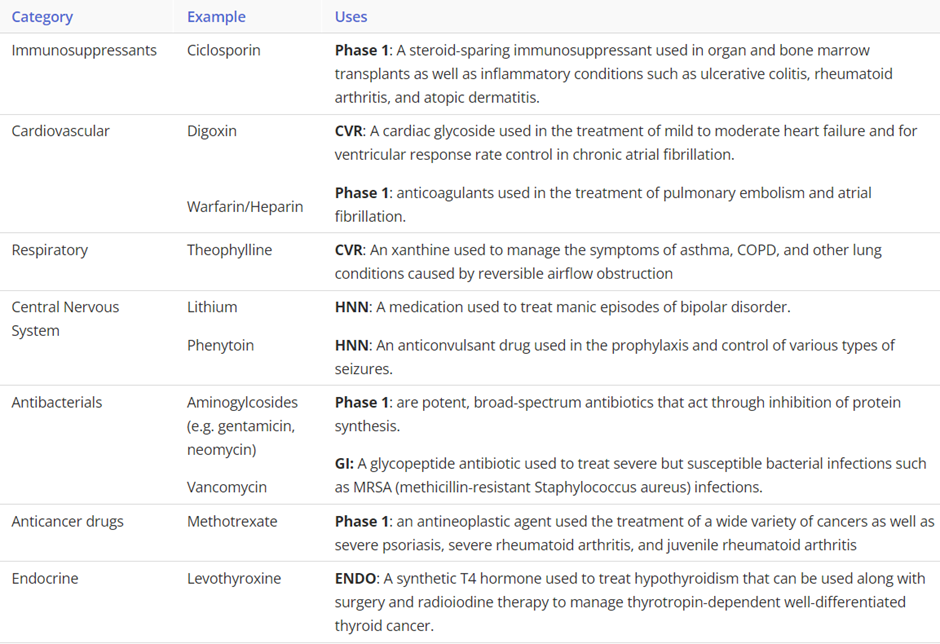

Clinicians prefer to use drugs where a large margin of safety permits the use of a standard dose without the discomfort, inconvenience and expense of monitoring, which entails sequential blood sampling and dose adjustment. However, there are still a number of drugs in use that have a narrow therapeutic index and are listed in the table below.

Identify common examples of where monitoring drug concentrations are important

Clinicians prefer to use drugs where a large margin of safety permits the use of a standard dose without the discomfort, inconvenience and expense of monitoring, which entails sequential blood sampling and dose adjustment. However, there are still a number of drugs in use that have a narrow therapeutic index:

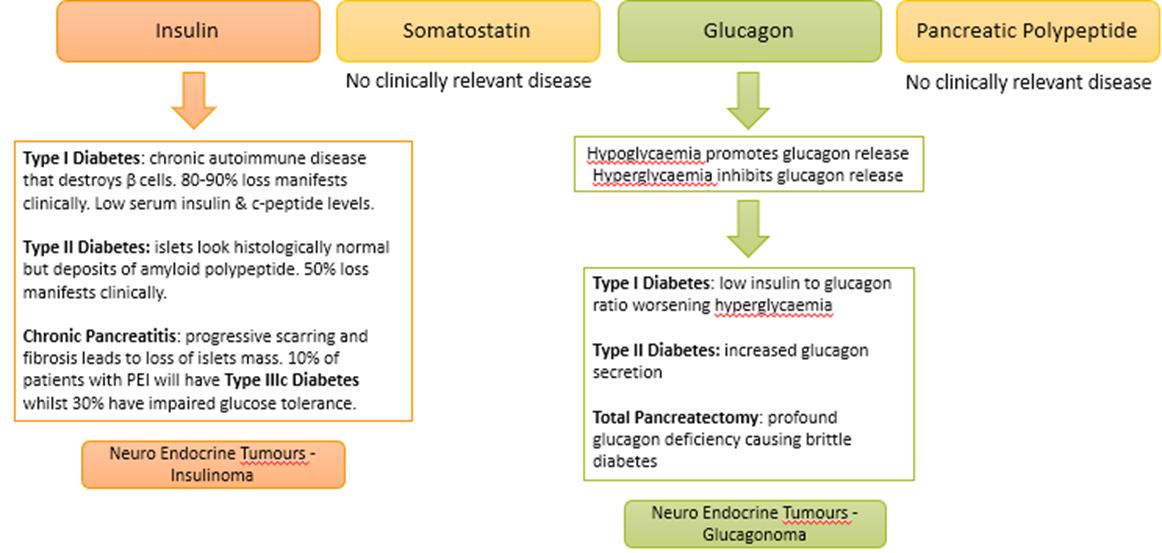

explain the function of the parasympathetic and sympathetic innervation on the pancreas

Autonomic Nervous System

•Parasympathetic innervation

•Vagus Nerve (CN X)

•Stimulates exocrine secretion from acinar cells

•Release of pancreatic fluid, insulin & glucagon

•Sympathetic innervation

•Splanchnic nerves (T5-T12)

•Causes vasoconstriction & inhibition of exocrine secretion

•Stimulates release of glucagon

•Inhibits release of insulin

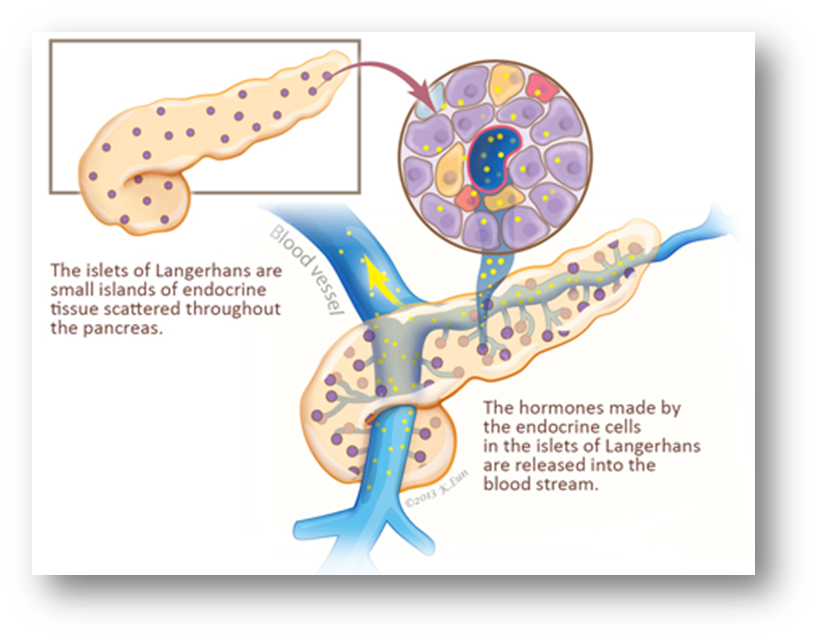

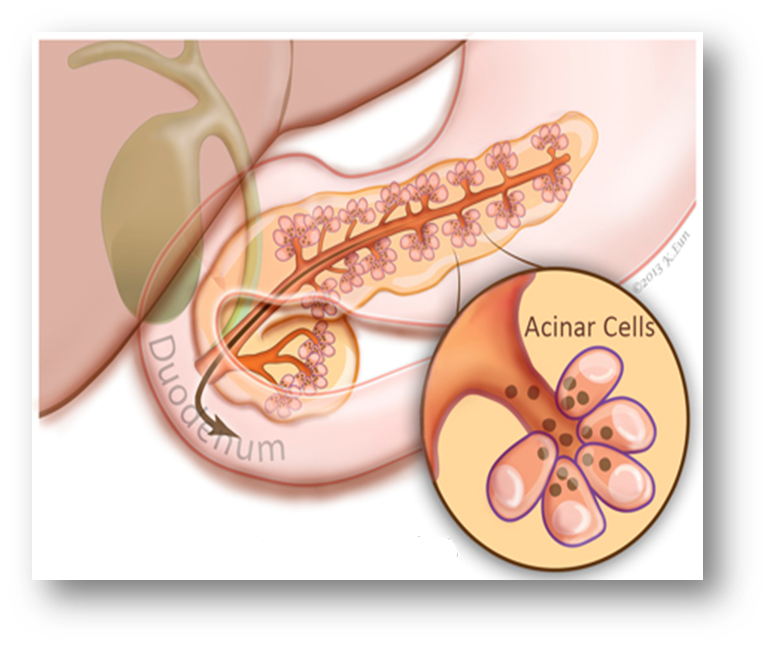

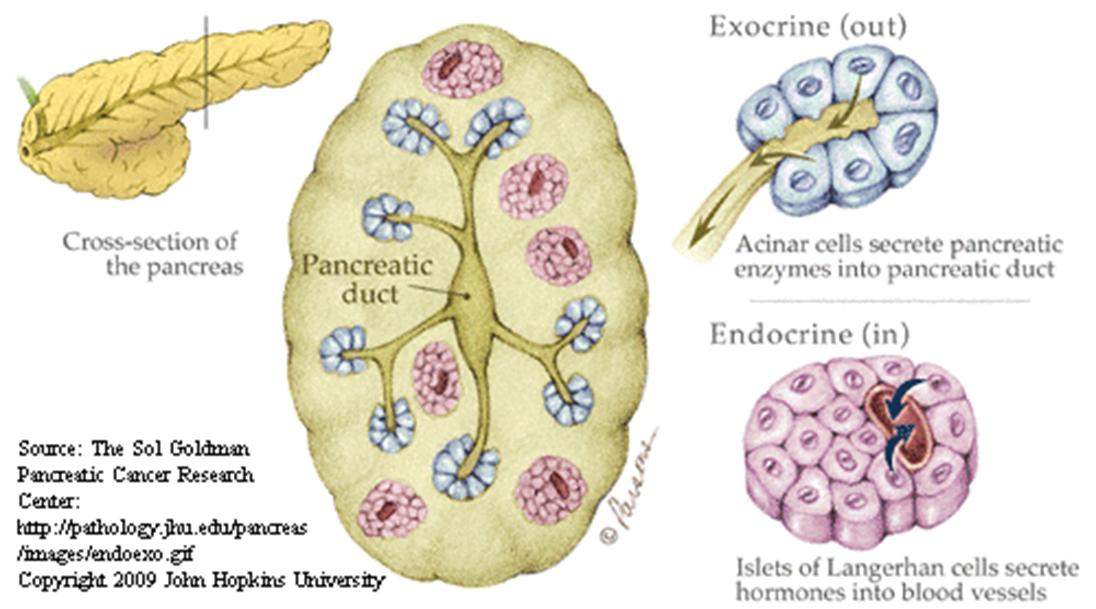

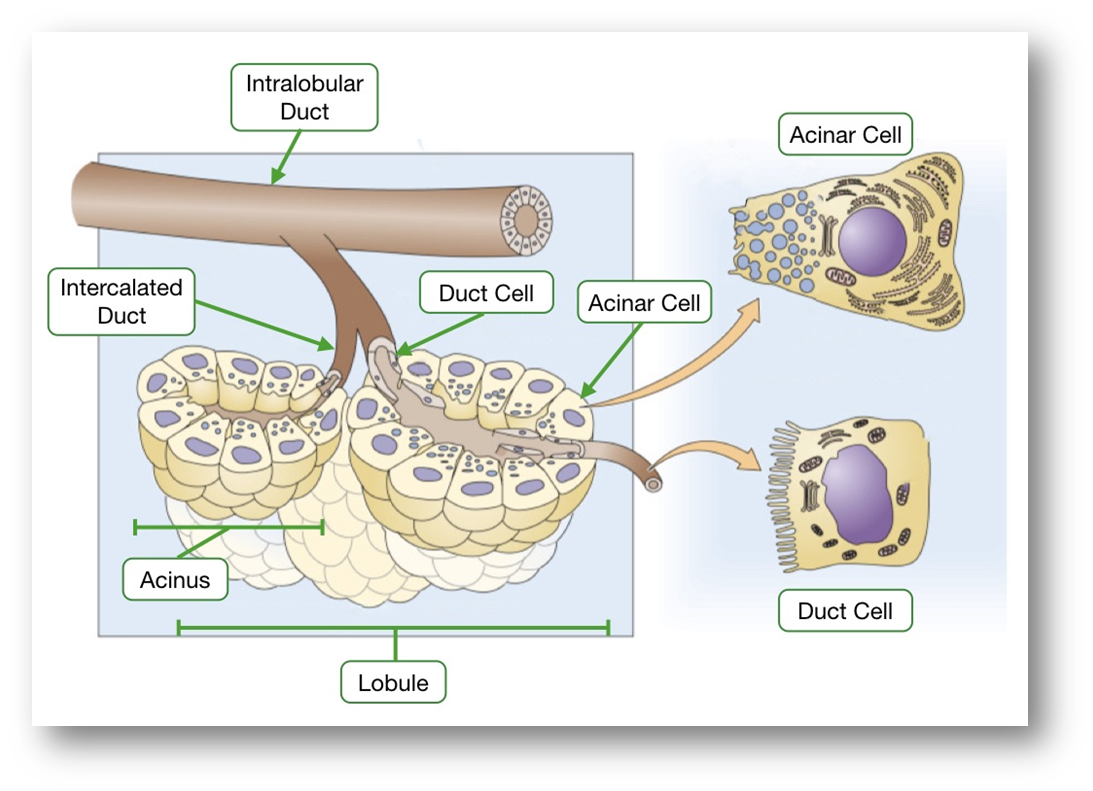

outline the histological structure of the pancreas

ENDOCRINE FUNCTION- Islets of Langerhans secrete hormones

EXOCRINE FUNCTION- Acinar cells secrete pancreatic enzymes

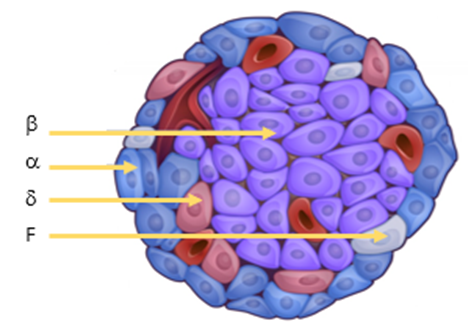

describe Langerhans islet cell types linking it to their function

Human’s have 1-2 million islets distributed evenly throughout the pancreas

Each islet contains approximately 1000 endocrine cells

The islets make up 2% of the normal human pancreas

There are 4 cell types:

Alpha Cells-

•15-19% of cells in the islet

•Secrete glucagon

Breakdown of glycogen in liver/muscle

Increase blood glucose

Beta Cells-

•70-80% of cells in the islet

•Secrete insulin

Increase the membrane permeability for glucose

Excessive glucose oxidation in tissues

Lowers blood glucose levels

Synthesis of glycogen in liver/muscles

Lowers the break down of protein

Delta Cells-

•5 % of cells in the islet

•Secrete somatostatin

Inhibits the release of GI secretion

Splanchnic vasoconstriction & reduces gut motility

F Cells (PP Cells)-

•1 % of cells in the islet

•Sparsely present in dorsal pancreas

•Secrete pancreatic polypeptide

Self regulates pancreatic secretions

Affects hepatic glycogen levels

Secretion of hormones into the blood –rich capillary supply

what is the clinical relevance of islet secretions?

describe the exocrine pancreas

•Comprises of the acinar cells (75-90% mass) and ductal cells (5%)

•Produces more protein per day than any other organ in the body (except lactating breast)

•1500-2500 ml of bicarbonate-rich fluid

•6-20g digestive enzymes

•Secretions are regulated by vagus nerve and gastrin levels (hormone that stimulates stomach acid production)

ACINAR CELLS-

Enzyme secretions from the acinar cells:

•Protease (Trypsin & Chymotrypsin): polypeptides to peptides

•Pancreatic Lipase: trigylcerides into fatty acids and monoglycerides

•Pancreatic Amylase: Carbohydrates into disaccharides/monosaccharides

•Other Enzymes: ribonucelase, deoxyribonuclease, gelatinase & elastase

•Some enzymes are released activated (e.g. amylase) and others (e.g. trypsin) are activated in the duodenum

DUCTAL CELLS-

Secretions from the epithelial cells that line the ducts

•Bicarbonate : base that is essential to neutralize gastric juices

•water

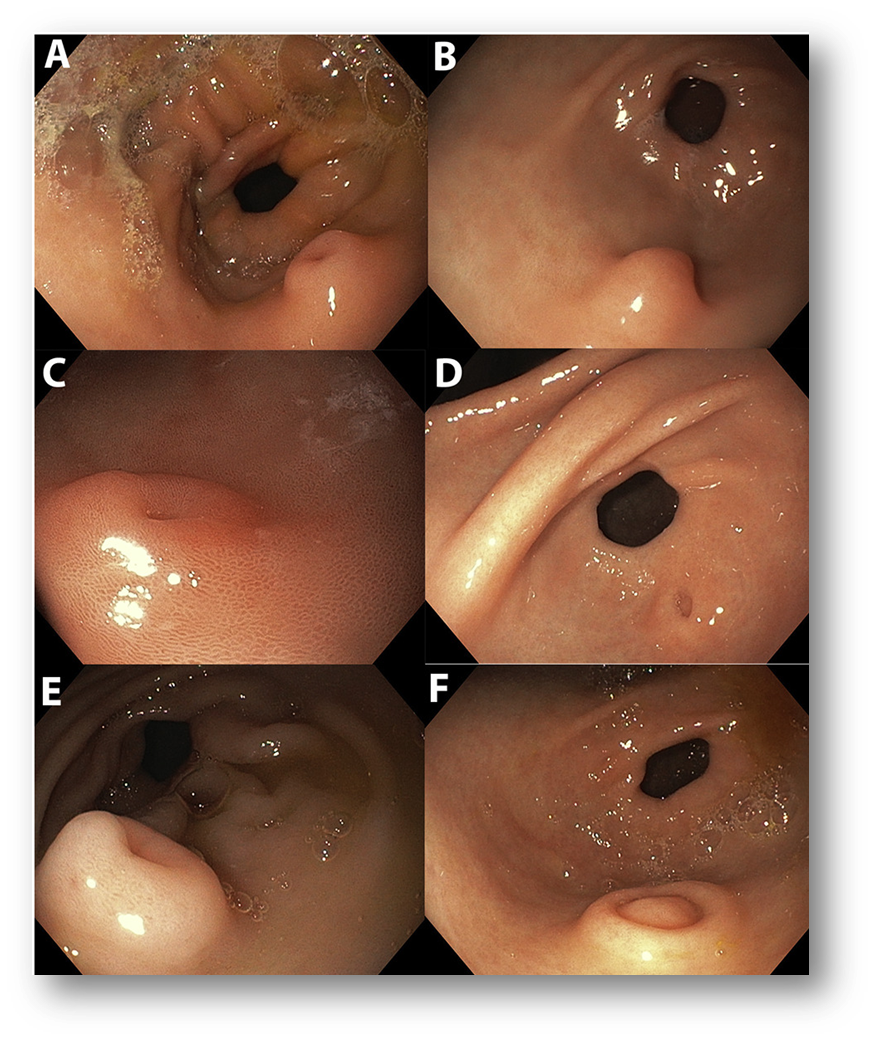

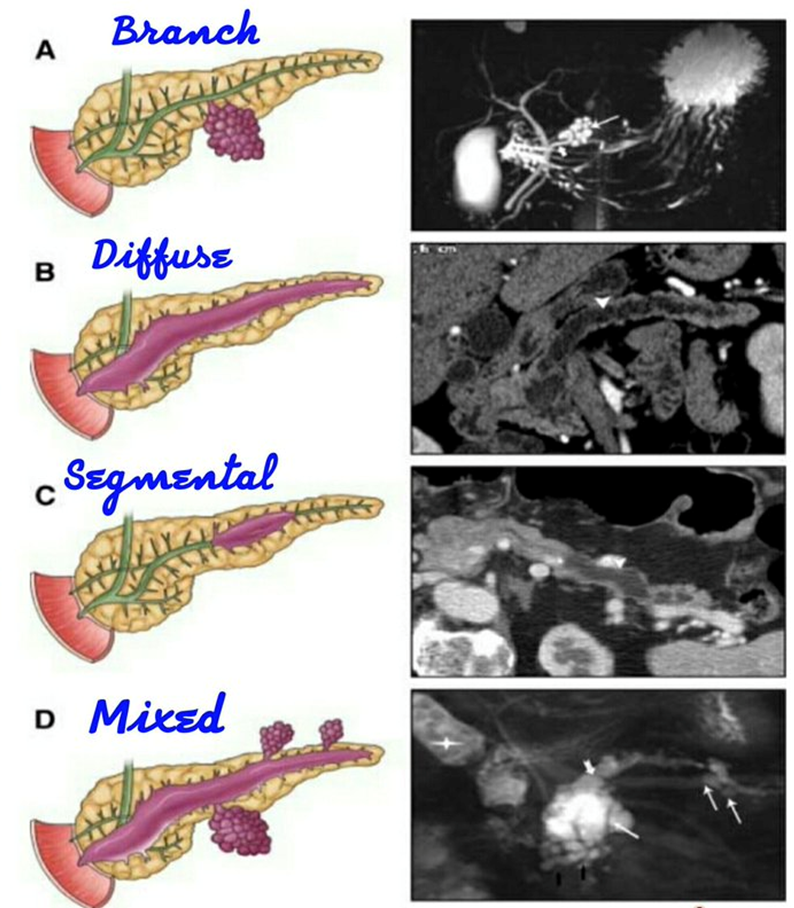

explain Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN)

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm

•Non-invasive mucin producing neoplasms of the Pancreatic Ductal epithelial cells

•Manifests as dilated ducts or cysts

Presentation

•Incidental, smokers

•70’s Pain (59%) and jaundice (16%) Weight loss (29%)

•Hx of pancreatitis (15%)

Main duct or side branch or mixed type

•MD IPMN – 60-90 % risk of malignancy (resection)

•SB-IPMN – high risk/worriesome features (selective resection)

Explain pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI)

•Malfunction of the exocrine pancreas

•Reduced digestive enzyme activity (mainly lipase)

Clinical manifestations

•Steatorrhea - excessive amounts of fat in your poop

•Flatulance

•Weight loss

•Abdominal pain

•Impaired quality of life

•Increased risk of complications due to:

Malnutrition

Changes in bone density

Increased gut motility

causes

how is pancreatic exocrine function assessed?

Often needed to help diagnose chronic pancreatitis where radiology is non-diagnostic

•Indirect tests – monitor the intestinal effects of secreted pancreatic enzymes

Faecal fat staining

72 hr faecal fat excretion (>7g/day is abnormal)

•Direct test – monitor the actual secretion of pancreatic exocrine products (e.g. enzymes or bicarb)

Faecal elastase

Serum Trypsinogen

Invasive test monitor secretions into the duodenum or pancreatic duct with a collecting device

what medications are given for pancreatic issues?

Insulin

•Lowers plasma glucose concentration

Somatostatin analogues- drugs that mimic the natural hormone somatostatin

•eg. Octreotide, Lanreotide

Pancreatic Enzyme Replacement Therapy (PERT)

•Creon (must be given with PPI, to improve its efficacy, as the enzymes in Creon can be inactivated by stomach acid. PPI reduces the amount of acid produced by the stomach)