lecture 8: historiography and archives

1/13

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

14 Terms

historiography

In the analysis of cases, we typically have a “background narrative”

We have a version of the “facts”

Background Narrative may be...

✓Core of our analysis

✓The premises under which we analyze the case

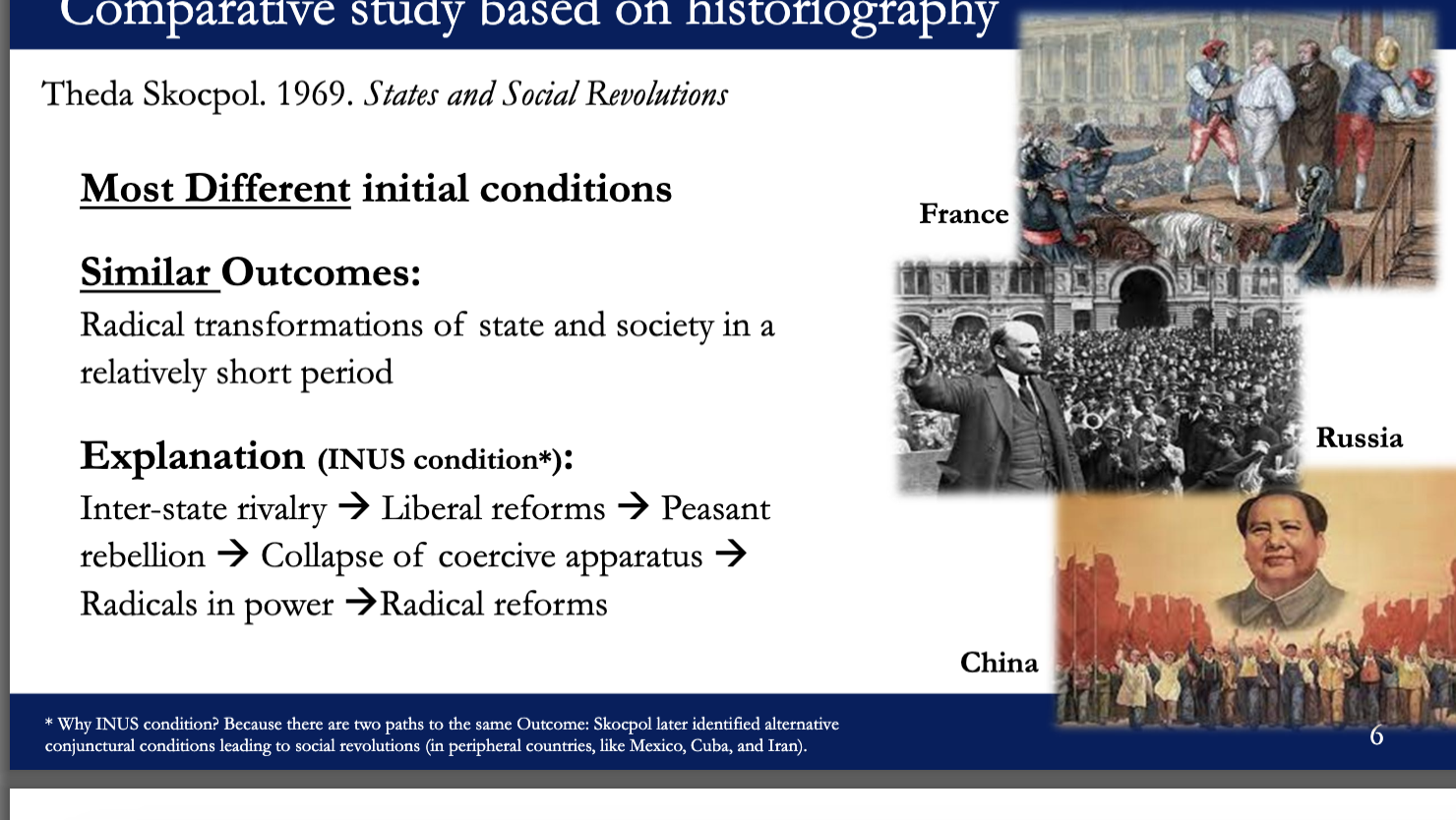

Core of our analysis: Skocpol’s study of revolutions classified France (late 18thcentury), Russia (early 20thcentury), and China (early 20thcentury) as revolutionary based on historiography 5

Premises of our analysis: Winward’s study of Indonesia presupposes a basic interpretation of what happened during the Suharto coup d’etat against the post-colonial elected government and the ensuing purges of communists (1965-66 —> starts with historiography

How do I collect data from historiography? step 1

Two steps...

1. Survey the “lay of the land” (state of the art)

I need to understand what historians have said about the period of interest and the different schools of historiography

I need a list of relevant publications

Does not need to be exhaustive nor I need to read more than the main argument

Point: Identify a good enough sample

articles:

journal(s) most likely to publish articles about my topic

review articles related to the subject, reviews of books

collection of survey articles

annualreviews.com (social sciences)

search engines

Leiden library, google scholar

How do I collect data from historiography? step 2

2. Text analysis: Active & Critical reading

Active = Read looking for specific elements

Critical = Assess these elements

Overall argument: What does the author say? How is this positioned vis-à-vis the literature on the subject

Look for it where it’s typically located: Intro and Conclusions

Argument’s structure: Understand the specific claims of which the overall argument is formed and the evidence that supports these claims

Read trying to answer these questions:

✓How sound is the argument? Are there contradictions? What does the author assume?

✓Is the evidence actually supporting the argument? How so?

How do I use primary sources?

To understand what archives and which documents I want to look at, reflect:

✓Fundamental questions: What happened? What were the key actors involved?

✓The scholarly problem: What are the debate’s terms and what evidence have historians used for their arguments? What does the evidence actually show? Do I see contradictory info?

Start from the easiest to access: In library and online

✓Published collections of documents: They have been edited with the most important docs

✓Published sources: Diaries, collections of personal papers, etc.

✓Online institutional archives. Ex: Artic Council’s archive (https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/home), International Court of Justice’s documents (https://www.icj-cij.org/advanced-search)

✓Newspaper archives. Ex: ProQuest historical newspapers through LU Library

When reading documents...

✓Start by piecing things together. For instance, create a timeline and weigh on events’ importance

Here, newspapers (and newspaper indexes) may be enough

✓What was the key actors’ worldview? How did they think? How did they intervene

Documents on meetings, speeches, articles...

Let sources...

➢Create new questions and identify new actors

➢Lead you to new primary sources

But “you’re not just gathering data as a kind of end in itself. You’re actively looking for answers. You’re trying to get a sense for what the story was”. Progressively, “you develop a sense for the texture, for the complexity, of a particular episode”.

question: how do you combine archival and historiographical sources?

problems with historiography and primary sources: sample bias

No such thing as “what truly happened

Historical accounts (historiography) always have theoretical , personal and political commitments

(Lustick’s position is that) It’s impossible to produce “neutral” accounts that simply report facts

Why? The author must:

✓Choose which events matter

✓Assign meaning to events (What is this?)

✓Assign meaning about the relationship between events (What caused this?)

In other words, interpret the events by constructing a narrative

Why don’t I just use only primary sources?

selection bias: Risk: Making inferences based on partial accounts, incomplete information, and misinterpretations

because we need to interpret the events by constructing a narrative

it will make the work of comparative/social sciences impossible - in both qual and quan

The challenge for social scientists using historiography as data is not finding accounts that give “the facts”—These do not exist.

The challenge is: What do I do, given that there are different interpretations?

Example: Moore’s biased selection of historiography

comparative case study of “paths (long periods) to the modern world” (disintegration of the feudal world)

based on historiography

1) capitalist democracy: uk, france, us

2)communist dictatorship: russia, china

3) fascism: germany, japan

neo marxist approach: explanations based power balance between social classes

landlords, peasants, and bourgeoisie

selection bias: he used classic historiography, but younger historians has already debunked that the glorious revolution was mostly motivated by economic interests, it was religious conflicts

consequence: Moore’s causal story about the similarities between UK, France, and US is wrong that revolts were motivated by economic/class interests —> he selected convenient historiography

4 “best practices” to mitigate selection bias and illustrates them with his study British-Irish relations in the 19th century

what is he not doing

✓Providing rules and procedures for distinguishing “accurate” vs “inaccurate” history books and articles—He remains agnostic (at best) about whether that’s possible

✓BUT he does not argue that all historical accounts should be treated as equally untrue or incomplete

Within the impossibility of producing neutral or factual records, some accounts are better

Do not look for the definite account of “what really happened” because there are different points of view... Look for transparency and self-reflection: —> not just what happened

Transparency about primary source collection and a systematic analysis

Reflection on what can and cannot be said with the primary sources at hand

Self-position within the scholarly research on a given period

4 best practices

Lustick’s 1993 book, Unsettled States

How do territories colonized with settlers become autonomous or independent? For example, Ireland from Britain or Algeria from France

It’s not obvious because these were long processes and many factors could potentially intervene

Based on these case studies, Lustick proposes an explanation that combines

a)Diffusion of new ideas

“Ideas” are usually regarded by social scientists as irrelevant or subordinated to explanations based on realpolitik

b)Partisan politics in the metropole

The impact of domestic politics on foreign policy, as opposed to a realist view of international relations

why do countries become independent

Explanation:

1.New ideas are published and influence a new generation through publications and networks. They are part of a market of new ideas —> alot of new ideas

2.An actor (“political entrepreneur”), who has been influenced by these ideas at a previous stage, advances these ideas by materializing them in policy packages, forming support coalitions, and tapping opportunities... —> ideas and partisan power come together

✓Thus, there is nothing inevitable about these ideas making it into policy, as the political entrepreneur can fail

✓Also, because there is a market of new ideas. So, there are more than one entrepreneurs trying to advance their ideas

3.The political entrepreneur also negotiate these ideas since she does not only want to advance these ideas but gain power

This is what Lustickrefers to as Antonio Gramci’s“war of position”—The politics of narratives and ideas24

The Case Study: Great Britain’s “Irish question”

•Irish independence from Great Britain was a long and complex process, involving violence, negotiation, and international change, from the late 18thcentury to the mid-20thcentury

Integral to that process was the change of ideas about Britishness (not just Irish nationalism): the English came to see the Irish as essentially different people, so that the cause of autonomy within GB caught traction (including sympathy within the English population)

Key moment: PM Gladstone (Liberal Party) supports Irish autonomy within the Union (Home Rule) for the first time, in the 1880s. It came as a surprise because the Liberal Party had rejected every past autonomy bill

Why as it key? It broke the dominant consensus that the “Irish cause” was unthinkable. It was also the culmination of the (gradual) disintegration of the “hegemonic” notion of Ireland and England as part of the same nation

Gladstone was the political entrepreneur

He was influence by the “historicist” turn in the market of ideas: a nation is formed by shared histories—contrary to the contractual ideas of the Enlightenment

Other versions of these notions of difference were about natural hierarchies (social Darwinism, racism)

Differently than others (especially in the Conservative Party), Gladstone was not un sympathetic to the Irish case, but only supported it actively until an opportunity for political advantage appeared

Evidence

Lustick found many monographs focused on 1880s parliamentary politics and the Liberal Party rule during that time

They had different takes on Gladstone’s motives, but they could be classified in two camps

✓Hagiographical narratives (praising Gladstone’s vision and self-interest)

diff nations within a nation state UK—> necessary condition

✓Reactions to Gladstone’s hagiography emphasizing self-interested behavior (political gain), each emphasizing different motives

Best practices” to mitigate selection bias (and be more persuasitve) step 1

can be combined

Note: Do not need to do them all, but can be combined

1. Be true to your school

First, acknowledge the “historiographical terrain” or “lay of the land”

Then, to construct the Background Narrative, choose a set of publications from one historiographical school, instead of cherry-picking from different publications across schools

Locate the school within the debate (why is it distinctive?) and be transparent about its theoretical, personal, and political commitments

Problem: Sometimes, a school of historiography has a narrow focus to provide facts and events to produce a complete Background Narrative useful for me.For instance, if focuses solely on the national level but overlooks what happens in the provinces.

Case Study: Lustickfocused on the historiography that emphasized the partisan politics embroiled in the Irish question

Best practices” to mitigate selection bias (and be more persuasitve) step 2

2. Explaining variance in the historiography

Treat different publications in your historiographic schools as data points: Construct the Background Narrative with bits from this school, emphasizing facts and events on which historians converge

Discuss why there is divergence in some respects: Do they use different sources? Do they dismiss pieces of evidence? Why?

Note whenever there are (partially) conflicting stories

Problem: It only works if the historiographical schools is vast enough (many author)

Case Study: It is clear that Gladstone produced political gains for his party: (a) United the Liberal Party around a policy that many came to view sympathetically, and (b) Broadened the party’s coalition with an alliance with the Irish nationalists.

However, historians within this school have conflicting accounts about the role of Gladstone’s ideology on his alliance with the Irish nationalists towards more autonomy. The main reason is that these authors simply focused only on Gladstone’s parliamentary career. —> goes beyond the school of thought—> be transparent

Best practices” to mitigate selection bias (and be more persuasitve) step 3

Quasi-triangulation

cross referencing with other methods

Another strategy is to produce my Background Narrative with facts and events corroborated by more than one school of historiography

Even more persuasive...

Problem: I may spread myself too thinly... It’s very difficultCase Study: Lustick did not do exactly this, but did a second best...

Defined key empirical implications (Lustick calls them “new facts”) that might be observed outside the chosen historiography

For example, Gladstone had been sympathetic to Irish autonomy for many years before proposing Home Rule →Gladstone’s memoir, which was picked up by his biographers

Verify the consistency of these empirical implications with the historiography

Do my chosen historians have evidence explicitly against them?

Best practices” to mitigate selection bias (and be more persuasitve) step 4

4. Explicit Triage (more transparency)

When writing my Background Narrative, indicate as much as possible the source of each part of the Narrative —> use references for everything

Indicate in footnotes whenever there are alternative versions of facts, and briefly explain why I rejected these versions

Problem: Excessive use of footnotes and going over publication limits (e.g., my thesis max. words number). Thus, be pragmatic!