Chapter 2.3 Developments in Europe

Note: This section is quite long, so I’d recommend clicking on headers to minimize them to be more efficient.

Caption: The Byzantine Empire reached its greatest extent under Emperor Justinian in the mid-sixth century C.E. It later lost considerable territory to various Christian European powers as well as to Muslim Arab and Turkic invaders.

Worlds of Christendom

Byzantine Empire

Definition: The surviving eastern Roman Empire and one of the centers of Christendom during the medieval centuries. The Byzantine Empire was founded at the end of the third century, when the Roman Empire was divided into eastern and western halves, and survived until its conquest by the Ottoman Empire in 1453 with the Sacking of Constantinople. Also known as Byzantium

Expanding and Contracting Christendom

Between 1200 and 1450, Christianity experienced both expansion and contraction, much like the Worlds of Islam (see Chapter 2.2)

In Europe, Christianity witnessed significant expansion, marked by the growth of powerful states and the spread of Christian influence into new territories.

In Asia and Africa, the Christian presence declined substantially due to the spread of Islam, with many regions that were once predominantly Christian becoming Muslim-majority areas, leading to conversions and the marginalization of Christian communities.

The Eastern Orthodox World: A Declining Byzantium and Emerging Rus

Decline of Byzantium and Influence on the Rus:

Byzantium, once a formidable Christian empire, entered a phase of decline during the 12th century, yet its cultural and religious legacies profoundly shaped the emerging Rus civilization in Eastern Europe.

The Rus assimilated Byzantine institutions, artistic styles, architectural techniques, and religious practices, contributing to the formation of their distinct cultural identity and societal structure.

Characteristics of Byzantium:

Byzantium, viewed as the continuation of the Roman Empire, preserved many late Roman institutions and cultural traditions, emphasizing education, philosophy, and the arts.

The establishment of Constantinople as the imperial capital in 330 C.E. solidified Byzantium's status as a center of political, cultural, and economic activity.

Constantinople’s highly defensible and economically important positioning at the Western end of the Silk Road helped ensure the city’s cultural and strategic importance for many centuries.

Caesaropapism and the Eastern Orthodox Church:

Def. of Caeseropapism: A political-religious system in which the secular ruler is also head of the religious establishment, as in the Byzantine Empire.

Byzantine governance was characterized by caesaropapism, where the emperor wielded considerable influence over both state and religious affairs, unlike the relative separation of church and state in Western Europe.

The Byzantian Emperor would be both a “caesar” (head of state) and the pope (head of the church)

This close relationship between political and religious authority facilitated centralized control over religious matters, with the emperor appointing patriarchs, intervening in theological disputes, and convening church councils.

The integration of church and state reinforced the unity of Byzantine society and shaped its religious landscape.

Eastern Orthodox Christianity and Imperial Authority:

Eastern Orthodox Christianity played a crucial role in legitimizing the authority of the Byzantine emperor as the God-anointed ruler, representing the earthly manifestation of divine glory.

Textbook Definition: Branch of Christianity that developed in the eastern part of the Roman Empire and gradually separated, mostly on matters of practice, from the branch of Christianity dominant in Western Europe; noted for the subordination of the Church to political authorities, a married clergy, the use of leavened bread in the Eucharist, and a sharp rejection of the authority of Roman popes.

The authority of Eastern Orthodox Christianity provided a cultural identity for Byzantine subjects, and it justified adherence to orthodox Christian beliefs and practices as a defining characteristic of the empire's population.

Tensions with the Roman Catholic Church and the Crusades:

Conflict between the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church escalated over time, culminating in a mutual agreement of representatives from both churches in 1054 that the real enemies were the Muslims.

The Crusades, initiated by the Catholic pope against Islam, further strained relations between the East and West, particularly highlighted by the seizure of the Eastern-owned Constantinople by Western forces during the Fourth Crusade in 1204, leading to irreparable ruptures within Christendom.

The “holy wars” waged by Western Christendom, especially against the forces of Islam in the eastern Mediterranean from 1095 to 1291 and on the Iberian Peninsula into the fifteenth century. Further Crusades were also conducted in non-Christian regions of Eastern Europe from about 1150 on. Crusades could be declared only by the pope; participants swore a vow and received in return an indulgence removing the penalty for confessed sins.

Expansion of Orthodox Christianity among the Rus:

Kievan Rus: A culturally diverse civilization that emerged around the city of Kiev in the ninth century C.E. and adopted Christianity in the tenth, thus linking this emerging Russian state to the world of Eastern Orthodoxy.

Around 1200, Eastern Orthodox Christianity experienced significant expansion among the Rus, Slavic peoples inhabiting present-day Ukraine and western Russia.

The adoption of Eastern Orthodoxy by Prince Vladimir of Kiev in 988 began a pattern of religious unity among the diverse peoples of the region and integrating Rus into broader networks of communication and exchange.

Cultural Influence and Borrowings from Byzantium:

Rus borrowed extensively from the Byzantine Empire, incorporating architectural styles, adopting the Cyrillic alphabet, embracing religious iconography, and implementing a monastic tradition emphasizing prayer and service.

These cultural borrowings from Byzantium contributed to the transformation of Rus into a distinct civilization with a unified religious identity and provided legitimacy to its rulers through religious affiliation.

Decline and Fall of Byzantium:

Despite periods of resilience, Byzantium entered a period of decline after 1085, marked by territorial losses to Western European powers, Catholic Crusaders, and Turkic Muslim invaders.

The final blow came in 1453 when the Ottoman Empire captured Constantinople, leading to the demise of the Byzantine Empire after over a millennium of existence.

AP Questions:

Why did the Byzantine Empire collapse?

External Invasions: The Byzantine Empire faced relentless assaults from aggressive Western European powers, Catholic Crusaders, and Turkic Muslim invaders, leading to significant territorial losses and weakening of imperial control.

Ended in 1453 with the Sacking of Constantinople

Internal Strife: Civil wars and internal conflicts plagued Byzantium, contributing to political instability and a gradual erosion of centralized authority.

Economic Decline: Economic pressures, including declining trade routes and financial strain from prolonged conflicts, weakened the empire's economic foundation, further exacerbating its decline.

In what ways did Eastern Orthodox Christianity differ from Roman Catholicism?

Authority Structure: Eastern Orthodox Christianity emphasized the authority of the patriarch and maintained a more centralized structure, with the Byzantine emperor exerting significant control over religious affairs. In contrast, Roman Catholicism recognized the authority of the pope in Rome as the supreme head of the Church.

Religious Practices: Eastern Orthodox liturgy featured distinct rituals and traditions, such as the extensive use of religious icons and a focus on mysticism. Roman Catholicism, on the other hand, emphasized doctrinal uniformity and the sacraments.

Theological Differences: Eastern Orthodox theology placed greater emphasis on the mystical aspects of faith and theosis (the process of becoming more like God), while Roman Catholic theology emphasized papal infallibility and the doctrine of purgatory.

How did links to Byzantium lead to the development of the new civilization in Kievan Rus?

Religious Influence: The adoption of Eastern Orthodox Christianity by Prince Vladimir of Kiev in 988 facilitated religious unity among the diverse peoples of Kievan Rus, providing a shared cultural identity and legitimizing the authority of rulers.

Cultural Borrowings: Kievan Rus borrowed extensively from Byzantine culture, incorporating architectural styles, adopting the Cyrillic alphabet, and embracing religious iconography. These cultural exchanges contributed to the development of a distinct civilization in Kievan Rus.

Integration into Trade Networks: Byzantine connections facilitated Kievan Rus's integration into broader networks of communication and trade, allowing for the exchange of goods, ideas, and technologies, which further stimulated the development of the civilization.

A Fragmented Political Landscape in Western Europe

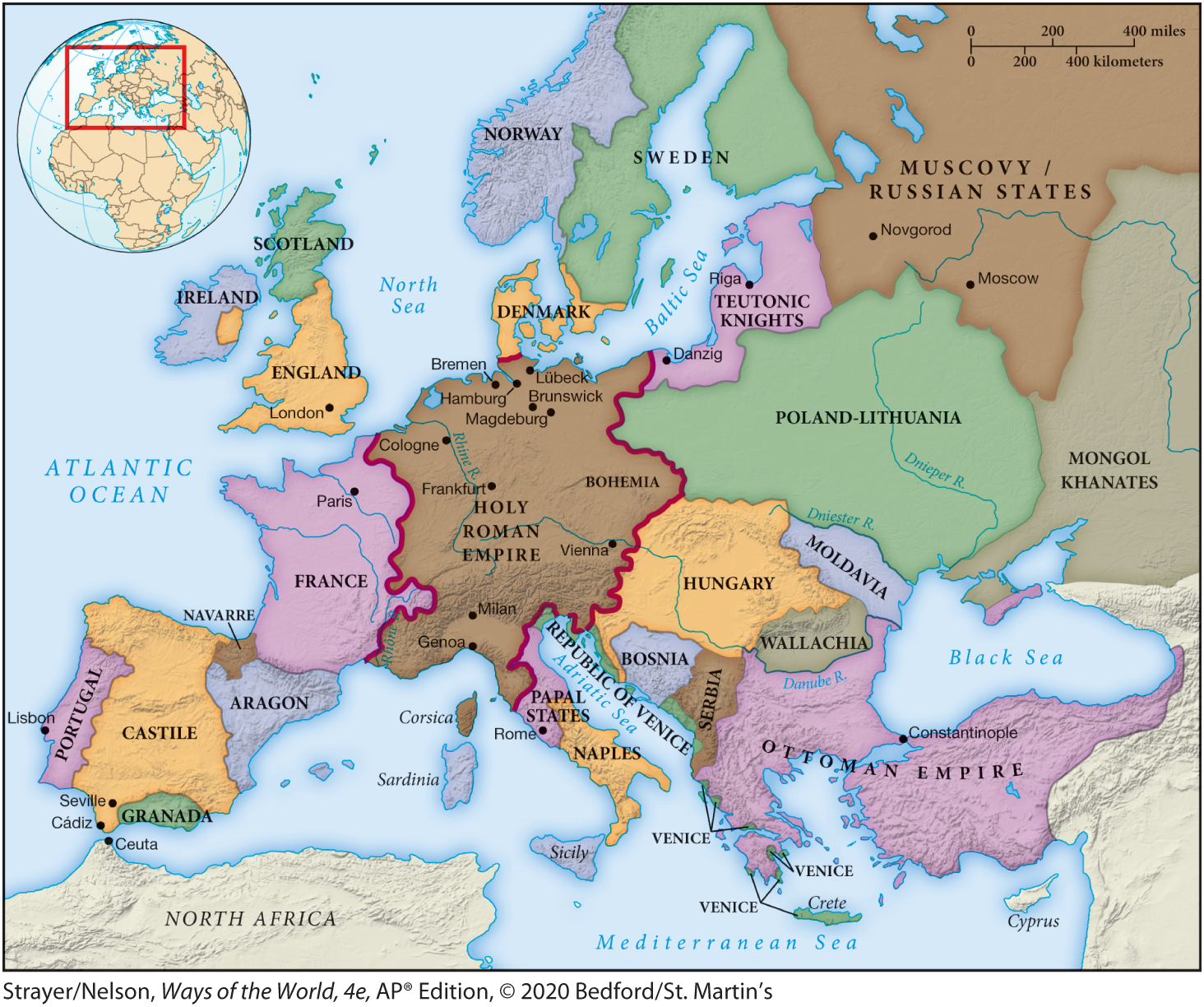

Europe in 1453: By the mid-fifteenth century Christian Europe had emerged as a system of competing states threatened by an expanding Muslim Ottoman Empire.

Europe in 1453: By the mid-fifteenth century Christian Europe had emerged as a system of competing states threatened by an expanding Muslim Ottoman Empire.

Vocabulary:

Western Christendom: The Western European branch of Christianity, also known as Roman Catholicism, that gradually defined itself as separate from Eastern Orthodoxy, with a major break occurring in 1054 C.E.; characterized by its relative independence from the state and its recognition of the authority of the pope.

Roman Catholic Church: Western European branch of Christianity that gradually defined itself as separate from Eastern Orthodoxy, with a major break occurring in 1054 C.E. that still has not been overcome. By the eleventh century, Western Christendom was centered on the pope as the ultimate authority in matters of doctrine. The Church struggled to remain independent of established political authorities.

Religion in Western Europe:

By 1200, Western Europe predominantly adhered to Roman Catholic Christianity, replacing some functions of the former Roman Empire with church institutions.

The Roman Catholic Church assumed roles in governance, education, and welfare, offering legitimacy to aspiring rulers and warlords and preserving remnants of Roman grandeur.

Despite widespread Christian conversion, remnants of pagan beliefs persisted, provoking continuous admonishment by clergy against the worship of natural entities like rivers, trees, and mountains.

Geopolitical Marginality:

Positioned at the far western end of the Eurasian landmass, Western Europe remained geographically distant from major trade routes like the Silk, Sea, and Sand Roads and centers of power.

Internally, geographical barriers such as mountain ranges and dense forests divided population centers, hindering political unity.

The threat of the Ottoman Empire in Anatolia and beyond discouraged Western Europeans from venturing out for trade.

Nevertheless, extensive coastlines and navigable river systems facilitated trade and agriculture, contributing to the region's economic productivity.

Decentralized Political Structure:

Unlike centralized states in other regions, Western Europe's political structure was highly decentralized and fragmented, characterized by feudalism and manorialism.

Manorialism: an economic system in feudal Europe where peasants worked on a lord's estate in exchange for protection and use of the land.

Power was predominantly wielded by landowning lords in thousands of independent estates or manors, each functioning as a self-sufficient unit.

Feudalism: Feudal lords controlled their independent domains, and lesser lords and knights pledged allegiance to greater lords or kings, often in exchange for land and military service.

Emergence of Competing States:

Post-1000 CE witnessed the gradual emergence of competitive states across Western Europe, marking a departure from the decentralized feudal order.

Monarchs embarked on processes of consolidation, gradually centralizing authority and delineating territorial boundaries.

Distinct states like France, England, Spain, and Scandinavia began to take shape, each developing its own governance structures and administrative institutions.

Militarization of Elite Society:

Frequent wars within Europe contributed to the militarization of European elite society, elevating the role and status of military men.

In contrast to China, where scholars and bureaucrats held greater prominence, European values and societal norms were heavily influenced by militaristic ideals.

Intense interstate rivalry spurred technological advancements in Europe, particularly in warfare, leading to significant progress in military technology, such as the utilization of gunpowder in cannons.

Technological Advancements and Adoptions:

European states made notable strides in technological innovation, facilitated by their highly competitive and militarized environment.

While inventions like gunpowder originated in China, Europeans were pioneers in its application for military purposes, notably in cannons by the early fourteenth century.

Progress in shipbuilding and navigation, including the adoption of the magnetic compass and sternpost rudder from China, enabled European maritime activity, paving the way for exploration and expansion in the 15th century.

Europeans also adopted the Mediterranean Lateen Sail, allowing vessels to sail against the wind.

Political Structure and Power Dynamics:

European rulers faced challenges from competing sources of power, such as the nobility and the Roman Catholic Church, leading to relatively weaker centralized authority.

The Roman Catholic Church wielded significant influence across all of Western Europe, boasting a hierarchical organization that extended its reach into nearly every community.

Rulers, nobles, and church authorities often engaged in competition but also reinforced each other, with the church offering religious legitimacy to rulers in exchange for protection and support.

Rise of Urban Independence:

The inability of kings, aristocrats, and church leaders to assert dominance created space for urban-based merchants to achieve unprecedented independence from political authority.

Many European cities, like Venice and Florence, became independent city-states where wealthy merchants exercised considerable local power.

The development of powerful, independent cities was a distinctive feature of European society, unlike the situation in China, where cities were integrated into the imperial structure with limited autonomy.

Later on: Influence on Capitalism and Representative Institutions:

Europe's weaker rulers allowed urban merchants greater freedom, laying the groundwork for the development of capitalism in later centuries.

The emergence of representative institutions, such as parliaments, reflected the need to accommodate the interests of competing social groups.

These immature parliaments, representing the clergy, nobility, and urban merchants, aimed to strengthen royal authority by consulting with major societal factions, rather than representing the broader populace.

AP Questions:

Why was Europe unable to achieve the same level of political unity that China experienced in this era?

Geographic diversity: Europe's varied geography, including mountain ranges and dense forests, posed significant obstacles to political consolidation, unlike the more homogeneous terrain of China.

Decentralized political structures: Europe lacked a centralized authority similar to China's bureaucratic system, leading to a multitude of fragmented states with competing centers of power. The feudal system in Europe, characterized by vassalage and decentralized lordship, contributed to political fragmentation as power was dispersed among numerous lords and nobles.

Based on this map (Europe in 1453), what factors account for the relative political and social fragmentation of Europe?

Geographic barriers: Europe's diverse geography, including mountain ranges and rivers, created natural boundaries that divided regions into separate political entities.

Feudalism: The feudal structure, with power decentralized among feudal lords, led to the emergence of small, independent states that were highly competitive and militaristic.

Dynastic rivalries: Competing claims to thrones and territories among European noble families resulted in political division and fragmentation across the continent.

An Evolving European Society and Economy:

Population Growth and Settlement Expansion:

With the High Middle Ages (1000-1300) European population experienced significant growth, rising from approximately 35 million in 1000 to around 80 million by 1340.

This population increase was facilitated by favorable climate conditions and greater stability, allowing for settlement expansion.

Lords, bishops, and religious orders played key roles in organizing new villages and settlements, often in areas previously considered unsuitable for habitation, such as forests, marshes, or wastelands.

Technological Innovations in Agriculture:

Advanced agricultural technologies emerged, including the development of a heavy wheeled plow designed for Northern European soils.

Europeans also implemented a new three-field system of crop rotation, enhancing land productivity and allowing for more efficient land use.

Adoption of iron horseshoes and more efficient collars, along with a shift towards horse-based plowing, contributed to increased agricultural output and supported population growth.

Rise of Mechanical Energy and Long-Distance Trade:

Europeans began utilizing mechanical sources of energy, such as windmills and water mills, which revolutionized various industrial processes.

These advancements marked a significant departure from previous reliance on human and animal muscle power for production.

Mechanical energy facilitated processes like grain milling, tanning, brewing, and iron manufacturing, driving economic growth and stimulating long-distance trade networks.

The increased production associated with this agricultural expansion stimulated growth for long distance trade, both within Europe and with the Islamic and Byzantian civilizations.

Environmental Impact of Agricultural Expansion:

The expansion of agriculture had significant environmental consequences, including deforestation and damage to freshwater ecosystems due to increased land tilling and the proliferation of water mills.

Overfishing and pollution from human waste also contributed to environmental degradation in many regions.

These environmental changes reflected the intensification of human activity and the growing impact of agricultural expansion on the natural world.

Population Growth in Towns and Cities:

London, Paris, and Venice experienced significant population growth in the 1300s, with London having about 40,000 people, Paris around 80,000, and Venice boasting perhaps 150,000 residents by the end of the fourteenth century.

Comparison with other major cities like Constantinople, Córdoba, and Hangzhou highlights the relative sizes of European urban centers in the medieval period, with Constantinople housing 400,000 people in 1000, Córdoba around 500,000, and Hangzhou exceeding 1 million in the thirteenth century.

Urbanization attracted diverse groups, including merchants, bankers, artisans, and professionals such as lawyers, doctors, and scholars, contributing to the growth and diversification of urban populations.

Impact on Division of Labor and Guilds:

Urbanization and economic growth led to the emergence of a more complex division of labor in European society, as various occupational groups organized themselves into guilds to regulate their professions.

Guilds, associations of people pursuing the same line of work, played a crucial role in organizing and regulating urban professions, ensuring standards of quality and protecting the interests of their members.

The formation of guilds facilitated specialization and professionalization within urban occupations, contributing to the growth of urban economies and the development of a skilled labor force.

Gender Dynamics and Changing Roles of Women:

Economic growth and urbanization initially provided significant opportunities for European women, who engaged in various urban professions such as weaving, brewing, milling grain, midwifery, and small-scale retailing.

Women's participation in the urban workforce was substantial, with records from twelfth-century Paris identifying 86 out of 100 occupations as involving women workers, including 6 exclusively female occupations.

However, the decline of artisan opportunities for European women by the fifteenth century, alongside the disappearance of most women's guilds and restrictions on women's participation in certain professions, reflected shifting gender dynamics and patriarchal norms tightening.

Role of the Church and Convent Life for Women:

The church offered women from aristocratic families an alternative to traditional roles through the secluded monastic life within convents, where they embraced poverty, chastity, and obedience, finding relative freedom from male control.

Convents provided women with opportunities for education and leadership, allowing them to exercise authority as abbesses and obtain a measure of independence.

However, by 1300, the independence enjoyed by women within convents was curtailed as male control tightened, reflecting broader societal shifts towards reinforcing gender hierarchies and patriarchal norms.

AP Continuity and Change: To what extent did European civilization change after 1000?

Political:

Expansion of settlements under the organization of lords, bishops, and religious orders reflected a trend towards greater centralization of power in emerging states.

Emergence of greater stability and state power allowed for the consolidation of authority, leading to a gradual loosening of serfdom's grip on peasants as monarchs exerted control over local lords.

Development of representative institutions or parliaments, such as the English Parliament, signaled a shift towards more inclusive governance structures accommodating contending social forces and fostering political participation.

Innovation:

Technological advancements in agriculture, including the heavy wheeled plow, horse-based plowing, and the three-field system of crop rotation, revolutionized farming practices, significantly increasing agricultural productivity and supporting population growth.

Utilization of mechanical energy sources such as windmills and watermills for various industries facilitated the mechanization of production processes, leading to increased efficiency and output.

Implementation of devices like cranks, flywheels, camshafts, and complex gearing mechanisms in manufacturing and industry enabled the development of more sophisticated machinery and production methods.

Economic:

Population growth and urbanization fostered economic opportunities, leading to the rise of towns and cities as centers of commerce, industry, and culture.

Expansion of long-distance trade networks within Europe and with Byzantium and Islam facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and technologies, contributing to economic growth and cultural exchange.

Introduction of new sources of energy and agricultural techniques, combined with increased trade and specialization, boosted productivity, stimulated economic growth, and laid the foundation for the commercial revolution.

Cultural:

Expansion of urban centers attracted diverse groups of people, including merchants, bankers, artisans, and professionals, fostering cultural exchange and innovation.

Formation of guilds to regulate professions and organize communities provided avenues for social mobility and collective action, shaping urban societies and economies.

Changing roles and opportunities for women, initially offering substantial opportunities in urban professions, reflected evolving social norms and economic structures but later faced restrictions and declining opportunities in artisan trades as patriarchal norms tightened.

Environment:

Impact of agricultural expansion and industrialization on the environment, including deforestation, overfishing, and damage to freshwater ecosystems, highlighted the ecological consequences of rapid economic growth and urbanization.

Adoption of new agricultural practices and technologies altered landscapes and resource utilization patterns, transforming rural environments and ecosystems to meet the demands of a growing population and expanding economy.

Social:

Transition from rural to urban lifestyles influenced social dynamics and division of labor, leading to the emergence of distinct urban and rural communities with their own social hierarchies and cultural norms.

Economic and technological changes led to shifting gender roles, with women initially enjoying expanded opportunities in urban professions but later facing constraints and declining opportunities as patriarchal norms reasserted themselves.

Redefinition of masculinity, with men increasingly seen as providers in urban marketplaces rather than warriors, reflected changing social and economic roles and expectations in medieval European society.

Western Europe Outward Bound

European Expansion and Engagement:

Population growth in Western Europe led settlers to clear new land, particularly on the eastern fringes of Europe, contributing to territorial expansion.

Economic growth facilitated increased contact with distant peoples and Eurasian commercial networks, as merchants, travelers, diplomats, and missionaries engaged in intensive interactions.

The Crusades:

Initiated in 1095 and spanning several centuries, the Crusades were viewed as holy wars authorized by the pope and undertaken at God's command, with religious fervor serving as their core motivation.

Crusaders received spiritual benefits such as indulgences, alongside material benefits like immunity from lawsuits and a moratorium on debts, attracting support from various social classes in Europe.

The most famous Crusades aimed to reclaim Jerusalem and holy places associated with Jesus from Islamic control, resulting in the temporary establishment of Christian states in the eastern Mediterranean, although these were eventually recaptured by Muslim forces by 1291.

Diverse Targets and Consequences of Crusading:

Crusading extended beyond the Islamic Middle East, targeting areas such as the Iberian Peninsula, lands along the Baltic Sea, Byzantine Empire, and Russia, among others.

While the Crusades had little lasting political or religious impact in the Middle East, they brought regions like Spain, Sicily, and the Baltic permanently into Western Christendom.

Interaction with the Islamic world through crusading facilitated cultural exchange, technological transfer, and intellectual diffusion, but also reinforced cultural barriers and deepened divisions between Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism.

Long-term Influences and Legacy:

Crusades contributed to the development of European empire-building ideologies and perpetuated the notion of divine sanction for conquest, evident in later colonial ventures.

Christian anti-Semitism was exacerbated during the Crusades, leading to massacres of Jews en route to Jerusalem and reinforcing cultural prejudices.

Images of the Crusades have remained politically and ideologically significant, shaping perceptions and interactions between the Christian West and Islam over subsequent centuries.

AP Causation: What were the major political and cultural effects of the Crusades?

Major Political Effects:

Territorial Expansion: The Crusades led to the temporary establishment of Christian states in the eastern Mediterranean, contributing to territorial expansion of Western Christendom.

Geopolitical Shifts: Crusading activities reshaped political boundaries and power dynamics in regions targeted by Crusaders, including the Levant and the Byzantine Empire.

European Engagement: Crusades fostered increased engagement of European powers in international affairs, leading to alliances, conflicts, and diplomatic interactions with distant regions and cultures.

Major Cultural Effects:

Cultural Exchange: Crusading facilitated cultural exchange between Europe and the Islamic world, introducing Europeans to new ideas, technologies, and customs.

Religious Intolerance: The Crusades exacerbated religious intolerance, particularly towards Muslims and Jews, fostering a climate of religious animosity and conflict.

Development of Western Identity: Crusades played a role in shaping Western Christian identity, reinforcing the sense of a distinct Christian civilization and cultural superiority over other religious groups.

Reason and Renaissance in the West:

Intellectual Autonomy in European Universities:

European universities, such as those in Paris, Bologna, Oxford, Cambridge, and Salamanca, emerged as centers of intellectual autonomy.

Scholars enjoyed a degree of freedom from religious or political authorities, although this autonomy was contested and never complete.

The universities became hubs for the pursuit of knowledge in various fields, including theology, law, medicine, and natural philosophy.

Rise of Rational Inquiry and Human Reason:

European intellectuals began to emphasize the role of human reason in understanding divine mysteries and the natural order.

Rational thought, initially applied to theology, gradually extended to other disciplines like law, medicine, and the study of nature.

The growing enthusiasm for rational inquiry led scholars to seek out and translate original Greek texts, particularly those of Aristotle, from the Greek-speaking Byzantine and Islamic worlds.

Impact of Aristotle's Works:

The works of Aristotle, with their logical approach and scientific temperament, made a profound impact on European intellectual thought.

Aristotle's writings became the foundation of university education and dominated Western European thought for centuries.

The integration of Aristotle's ideas into Christian doctrine, notably by theologians like Thomas Aquinas, laid the groundwork for the later Scientific Revolution and the secularization of European intellectual life.

Emergence of the European Renaissance:

Definition: A “rebirth” of classical learning that is most often associated with the cultural blossoming of Italy in the period 1350–1500 and that included not just a rediscovery of Greek and Roman learning but also major developments in art, as well as growing secularism in society. It spread to Northern Europe after 1400.

Causes of the Renaissance:

Revival of Classical Knowledge: The Renaissance was fueled by a renewed interest in the art, literature, and philosophy of ancient Greece and Rome. The fall of Constantinople in 1453 led to the migration of Greek scholars to Italy, bringing with them Greek manuscripts and knowledge.

Wealth and Patronage: The prosperous commercial cities of Italy, such as Florence and Venice, became centers of wealth and patronage for the arts.

Humanism: Humanism, a cultural and intellectual movement that emphasized the value of human beings, their capabilities, and their achievements, played a crucial role in the Renaissance. Humanists advocated for a return to classical learning and a focus on individualism, secularism, and human potential.

Technological Advances: Technological advancements, such as the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg around 1440, facilitated the spread of knowledge and ideas. The dissemination of printed books made classical works more accessible to a wider audience, contributing to the intellectual climate of the Renaissance.

Effects of the Renaissance:

Intellectual Advancement: The Renaissance spurred intellectual advancements in various fields, including literature, philosophy, science, and mathematics. Scholars engaged in critical inquiry, questioning traditional beliefs and embracing empirical observation. The scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries owes much to the intellectual climate fostered by the Renaissance.

Cultural Transformation: The Renaissance marked a cultural transformation in European society, shifting focus from religious authority to individualism, secularism, and human achievement.

Expansion of Knowledge: The Renaissance laid the groundwork for the Age of Exploration and the Scientific Revolution by promoting curiosity, exploration, and discovery. Advances in navigation, cartography, and astronomy fueled voyages of exploration

Beginning in the commercial cities of Italy around 1350-1500, the European Renaissance represented a revival of interest in the ancient past.

Educated citizens of these cities sought inspiration from the art and literature of ancient Greece and Rome, aiming to surpass these cultural standards.

Renaissance culture, characterized by secularism, individualism, and a focus on worldly affairs, challenged the religious orientation of medieval Europe and signaled the dawn of a more capitalist economy.

In what ways did the rediscovery of Greek philosophy and science affect European Christianity?

Shift in Worldview: The adoption of Greek philosophical methods and scientific inquiry influenced European Christians' worldview, emphasizing the importance of reason, observation, and empirical evidence. This shift challenged the primacy of religious authority in explaining natural phenomena, paving the way for the development of modern science and secular thought in the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment.

The rediscovery of Greek philosophy and science during the Renaissance posed challenges to traditional Christian beliefs. Ideas from ancient Greek thinkers like Aristotle and Plato contradicted certain aspects of Christian doctrine, leading to tensions between religious authorities and proponents of classical learning. Thus movements for secularism like the Protestant Reformation and 30 years’ war occurred in the later centuries.