Chapter 9.1 Dawn of Industrialization

The Global Context

Population Growth and Energy Crisis

From 1400 to the early 19th century, the global population increased from about 375 million to approximately 1 billion. This surge led to heightened demands for resources.

Western Europe, China, and Japan experienced a significant energy crisis due to the depletion of traditional fuels like wood and charcoal, which became scarce and costly.

Introduction of New Energy Sources

The Industrial Revolution marked a shift to new sources of energy, notably fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas, which supplemented and largely replaced older sources like wind, water, and muscle power.

The discovery and use of guano (seabird excrement) as a potent fertilizer on the islands off the coast of Peru revolutionized agriculture by enabling intensive farming practices that supported larger human and animal populations.

Technological Innovations

Initial technological advancements began in 18th-century Britain with innovations that transformed cotton textile production.

The coal-fired steam engine was the pivotal breakthrough that drove machinery, providing a powerful and limitless source of energy that could operate machines, locomotives, and ships far more efficiently than previous power sources.

The technological advancements soon expanded beyond textiles to industries such as iron and steel production, railroads, steamships, food processing, and construction.

A second wave of the Industrial Revolution later focused on the development of chemicals, electricity, precision machinery, and communications technologies like the telegraph and telephone.

Agricultural Transformations

Mechanical reapers, chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and refrigeration significantly modernized agriculture, shifting it from traditional methods to more scientifically driven practices.

Cultural Impact and Innovation

A pervasive "culture of innovation" emerged, characterized by a widespread belief in continual improvement and technological progress. This cultural shift supported sustained technological innovation and industrial expansion.

Economic and Social Outcomes

In Britain, where the Industrial Revolution originated, industrial output increased fiftyfold between 1750 and 1900, demonstrating an unprecedented capacity for wealth production.

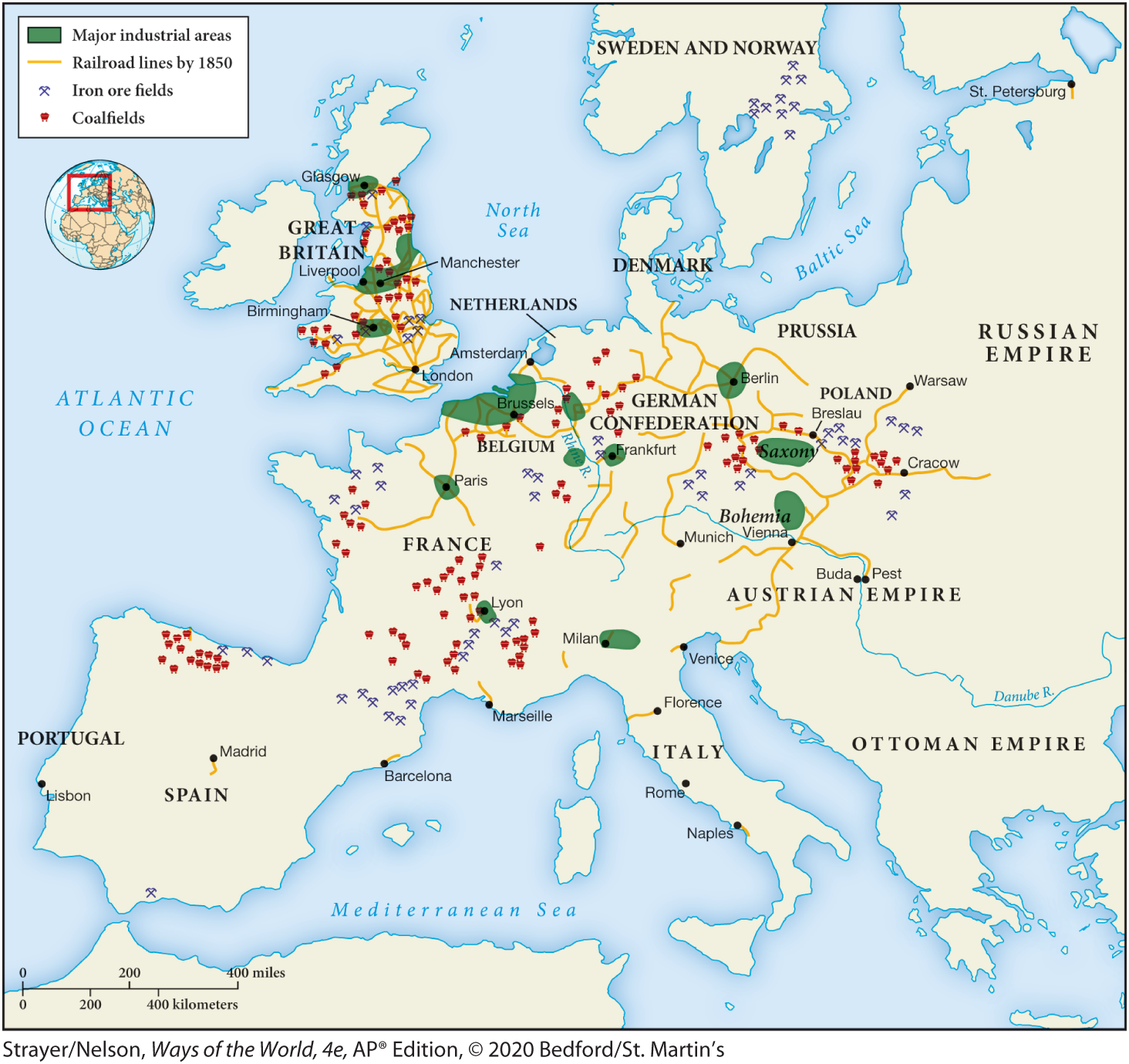

The Industrial Revolution gradually spread from Britain to Western Europe and, in the latter half of the 19th century, to the United States, Russia, and Japan, eventually becoming a global phenomenon in the 20th century.

Environmental Impact

The extensive extraction of nonrenewable resources had a negative impact on the environment, including landscape alterations, river pollution, and significant air pollution in urban areas, exemplified by the "Great Stink" of the Thames in 1858.

The Industrial Revolution was the start of the Anthropocene era, where human activities started to have a significant, observable impact on Earth's geology and ecosystems.

AP Questions:

In what ways did the Industrial Revolution mark a sharp break with the past? In what ways did it continue earlier patterns?

Sharp Break with the Past: Innovations in energy and socioeconomic changes on an international scale.

Energy Transition: The Industrial Revolution introduced a fundamental shift in energy sources from organic to inorganic, moving from reliance on animal muscle, water, and wood to coal and later to oil and natural gas. This shift enabled much higher energy yields, facilitating greater production capacity and efficiency.

Unprecedented Technological Innovation: Innovations such as the steam engine, which provided a new and powerful source of energy, and the mechanization of textile production fundamentally changed manufacturing processes.

Urbanization and Labor Changes: The Industrial Revolution prompted mass urbanization, a stark contrast to the predominantly rural and economically agrarian societies of the early modern period. Cities became centers of industrial production and labor, drawing populations from rural areas in unprecedented numbers.

Rise of Factory System: The factory system replaced the guilds and cottage industries of the early modern era, centralizing production in large facilities that employed vast numbers of workers under disciplined and timed conditions, fundamentally changing the nature of work and labor relations.

Transition from Mercantilism to Capitalism: The Industrial Revolution facilitated a shift from mercantilism, where national economies were dominated by state controls and regulations designed to increase national wealth through strict control over trade, to capitalism, which emphasizes private ownership, individual entrepreneurship, and market mechanisms. This change enabled more direct investment in industries, encouraged competitive practices, and fostered innovation, all of which were crucial for the scale and speed of industrial development and export.

Continuation of Earlier Patterns: Picked up on existing agricultural techniques and the wealth accumulated from economic globalization

Economic Globalization: While the early modern era saw the beginnings of global trade networks, the Industrial Revolution expanded and intensified these connections, with industrial goods flowing out of Europe and raw materials flowing in from colonies and other regions.

Capital Accumulation and Investment: The growth in capital accumulation that began during the early modern era with the expansion of trade and colonization continued and accelerated. The Industrial Revolution was financed by the wealth accumulated through these earlier economic activities, including profits from the slave trade and colonization.

Continued Improvement in Agricultural Production: Techniques such as crop rotation and selective breeding that began during the Agricultural Revolution of the early modern period continued to be refined and expanded during the Industrial Revolution, supporting larger urban populations.

Describe the difference between the first and second Industrial Revolution.

First Industrial Revolution (Late 18th to Early 19th Century):

Focus on Textiles and Steam: Centered on the mechanization of textile production and the introduction of the steam engine, which revolutionized transportation and manufacturing.

Primary Energy Source: Coal was the primary energy source, powering steam engines and furnaces.

Second Industrial Revolution (Late 19th to Early 20th Century):

Diversification of Industry: Expanded beyond textiles to include steel production, chemicals, and electricity, marking a diversification in the types of industries and products.

Technological Advancements: Featured major innovations such as the internal combustion engine, electricity, and telecommunications (telegraph and telephone).

Global Impact: Had a more global impact, with industrialization spreading to new regions, including Japan and parts of Western Europe outside of Britain.

Why might have Europe been an unlikely place for the Industrial Revolution to begin? Why might it have been likely?

Unlikely Reasons:

Political Fragmentation: Before the Industrial Revolution, Europe was politically fragmented into many small principalities and kingdoms, which could have hindered unified economic policies that supported industrial growth.

Agricultural Focus: Large portions of Europe were primarily agricultural before industrialization, with limited technological advancements in other sectors.

Likely Reasons:

Scientific Advancements: Europe had just undergone various theological developments that led to more popular ways of individualism: The Protestant Reformation, Scientific Revolution, and Enlightenment.

Access to Resources: European countries had access to abundant resources, either domestically or through their colonies, which were crucial for industrial development.

Capital Accumulation: The wealth accumulated from trade, especially from colonialism, provided the capital necessary to invest in new industrial technologies and infrastructure.

Competitive States: The competitive nature of European states fostered technological advancements and military innovations that could be adapted for industrial use.

Britain, the First Industrial Society

An overview: Economic Transformation during the Industrial Revolution

An overview: Economic Transformation during the Industrial Revolution

Massive Increase in Industrial Output:

The Industrial Revolution marked a significant increase in production and efficiency, exemplified by the British textile industry, which saw cotton usage soar from 52 million pounds in 1800 to 588 million pounds by 1850.

Coal production in Britain also dramatically increased, from 5.23 million tons in 1750 to 68.4 million tons a century later, supporting the energy demands of various industries.

Expansion of Railroads:

The development of railroads was a hallmark of the Industrial Revolution, with extensive networks being built across Britain and Europe, facilitating faster movement of goods and contributing to economic integration.

Shift from Agriculture to Industry:

Traditionally dominant sectors like agriculture declined in relative importance as mining, manufacturing, and services expanded.

In Britain, by 1891, agriculture accounted for only 8 percent of the national income and employed less than 8 percent of the workforce by 1914, underscoring the shift towards an industrial-based economy.

Preview of Social Transformation during the Industrial Revolution

Transformation of Daily Life:

The Industrial Revolution brought about profound changes in daily life, described by historians as more significant than any changes in the previous 7,000 years.

These changes were most evident in Great Britain, which emerged as the world's first industrial society.

Destruction and Creation of Social Structures:

The early stages of the Industrial Revolution destroyed traditional ways of life, leaving people to adapt and find new ways of living.

This period was marked by significant social conflict and insecurity, as old social structures were dismantled and new ones slowly emerged.

Varied Impact on Different Social Groups:

The effects of the Industrial Revolution were not uniform across all segments of society. While some groups experienced improved standards of living and new opportunities, others faced hardship and upheaval.

The disparities in impact led to ongoing debates about the human gains and losses brought about by industrialization.

The British Aristocracy

Economic Stability and Political Influence:

Despite the sweeping changes of the Industrial Revolution, the material wealth of the British aristocracy remained largely unaffected initially.

In the mid-nineteenth century, a small number of aristocratic families owned more than half of Britain's cultivated land, which was primarily managed by tenant farmers who employed agricultural wage laborers.

The ongoing demand for food, driven by a rapidly growing population and urbanization, sustained the economic viability of aristocratic landholdings.

Aristocrats continued to exert considerable influence in the British Parliament throughout much of the nineteenth century.

Decline of Aristocratic Dominance:

Despite maintaining material wealth, the aristocracy's societal dominance began to wane as the century progressed, primarily due to the rise of industrial wealth.

Urban wealth, generated by new industrialists, manufacturers, and bankers, became increasingly significant, diminishing the relative influence of land-based wealth.

By the century's end, landownership was no longer the primary basis for wealth, as industrial and commercial leaders began to dominate major political parties.

Although their political power declined, aristocrats maintained high social prestige and personal wealth, with many finding roles in the British Empire as colonial administrators or settlers, providing a new sphere for maintaining their status.

The Middle Classes

Upper Middle Class Integration into Aristocracy:

The most visible beneficiaries of industrialization were the wealthy industrialists, mine owners, bankers, and merchants who formed the upper echelons of the middle class.

These individuals often assimilated into aristocratic lifestyles, purchasing estates, securing parliamentary seats, sending their children to prestigious universities, and accepting noble titles, effectively blurring the lines between the traditional aristocracy and the nouveau riche.

Expansion and Cultural Influence of the Broader Middle Class:

More numerous than the upper middle class were the smaller businessmen, professionals like doctors, lawyers, engineers, and academics who were indispensable in an industrial society.

This broader middle class shaped a distinct societal culture characterized by liberal values such as constitutional government, private property, free trade, and limited social reform.

The Reform Bill of 1832, driven by middle-class activism, expanded voting rights to many middle-class men, though women of the same class were excluded.

Cultural values of this class emphasized thrift, hard work, morality, and cleanliness, as popularized by Samuel Smiles in his book Self-Help, which contrasted the middle class's enterprise with the poverty of the lower classes, attributing the latter's struggles to personal failings.

The Ideology of Domesticity:

Middle-class women were increasingly envisioned as homemakers, tasked with creating a supportive and morally uplifting home environment to shield their families from the harsh realities of the industrial capitalist world.

The ideology of domesticity defined the ideal role of women as centered around homemaking, child-rearing, charitable activities, and engaging in culturally "refined" activities such as embroidery, music, and drawing. This ideology placed women firmly within the private sphere of the home, contrasting sharply with men's roles in the public and professional spheres.

Economic and Social Expectations:

The emergence of the middle-class "lady" was facilitated by the new wealth generated during the Industrial Revolution, allowing families to emulate the aristocratic norm where women were detached from productive labor.

Margaretta Greg's statement in 1853 that women should not engage in paid employment underscores the prevailing view that middle-class women's roles should not intersect with monetary pursuits. Employing a servant became a status symbol, reflecting a family's ascent into the comfortable middle class.

Temporary Withdrawal from the Workforce:

Initially, middle-class women withdrew from the labor force, focusing instead on domestic responsibilities. However, by the late nineteenth century, societal changes and economic needs prompted many of these women to enter professions such as teaching, clerical work, and nursing.

This shift was partly driven by the necessity of contributing to family income or personal fulfillment, challenging earlier notions of women's exclusive confinement to the home.

Rise of the Lower Middle Class:

The Industrial Revolution also fostered the growth of a substantial lower middle class, comprising individuals working in the expanding service sector, including clerical and sales positions.

By the end of the nineteenth century, this group made up about 20% of Britain's population, providing new professional opportunities for women, although they were often expected to leave their jobs upon marriage.

Increase in Female Employment:

The period from 1881 to 1901 saw a dramatic increase in the number of female secretaries, rising from 7,000 to 90,000. The majority of these women were single, reflecting societal expectations that women should cease working after marriage.

Consumerism and Class Identity:

The ability and eagerness of the middle classes to purchase a wide range of material goods significantly contributed to the sustainment and expansion of the industrial economy.

This consumption not only underscored the economic viability of industrialization but also reinforced middle-class values and distinctiveness from the working class, which was still largely associated with manual labor.

AP Questions:

How did industrial production transform the social position of England’s aristocratic class?

Economic Displacement: The emergence of industrial wealth diminished the relative economic power of the landowning aristocracy, as the new industrialists, manufacturers, and bankers accumulated wealth that often surpassed that derived from land ownership.

Political Influence: While the aristocracy initially continued to dominate the British Parliament, their influence waned over the nineteenth century as urban wealth and the industrial business class began to assert more control, changing the traditional power dynamics.

Social Prestige and Adaptation: Despite a decline in direct economic and political power, the aristocracy retained considerable social prestige. Many aristocrats adapted by taking roles in the expanding British Empire, serving as colonial administrators or settlers, which provided new avenues for maintaining status and influence.

What was the effect of industrial production on England’s middle class?

Expansion and Prosperity: Industrial production led to the significant expansion and differentiation of the middle class. The upper middle class, including factory owners and bankers, gained substantial wealth, often rivaling or surpassing the aristocracy.

Cultural and Social Influence: The broader middle class, including professionals and smaller businessmen, became the primary proponents of liberal values such as constitutional government, private property, and free trade. Their influence shaped political reforms, including the Reform Bill of 1832, which expanded their political rights.

Rise of the Lower Middle Class: The service sector expansion created a sizable lower middle class engaged in clerical, administrative, and retail jobs, further diversifying the middle-class spectrum and contributing to its overall growth and significance in society.

What changes in middle-class gender roles and family dynamics occurred during the Industrial Revolution?

Emergence of the Cult of Domesticity: Middle-class women were increasingly idealized as homemakers and moral guardians, responsible for creating a nurturing and morally uplifting home environment, shielding the family from the perceived moral threats of the industrial capitalist society.

Consumerism and Domestic Sphere: Women's roles expanded within the domestic sphere to include management of household consumption and engagement in "shopping," a newly significant activity that underscored their influence in the consumer economy.

Professional Opportunities and Limitations: While middle-class women began to enter professions such as teaching, nursing, and clerical work, these opportunities were often restricted to single women, with societal expectations that they would leave the workforce upon marriage.

Long-term Shifts: The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw more profound shifts as middle-class women increasingly advocated for and achieved greater participation in public and professional life, laying the groundwork for future feminist movements.

Laboring Classes in 19th c. Britain

Demographic Shifts and Urbanization:

During the nineteenth century, the majority of Britain's population transitioned from rural to urban settings due to industrialization.

Cities like Liverpool experienced explosive population growth, with its population increasing from 77,000 to 400,000 in the first half of the century.

By 1851, over half of Britain's population resided in towns and cities, marking a significant shift from the predominantly rural populations of earlier centuries.

Living Conditions in Urban Areas:

Rapid urbanization led to overcrowded and unsanitary living conditions, with cities like London growing to over 6 million inhabitants by the century's end.

Urban workers faced challenging environments characterized by poor sanitation, inadequate housing, insufficient public services, and frequent epidemics.

These conditions contributed to a low average life expectancy of only 39.5 years by 1850, a decline from earlier centuries.

Economic and Social Disparities:

The industrial revolution exacerbated the divide between the wealthy and the poor, with minimal personal contact between these groups.

Benjamin Disraeli's novel Sybil highlighted the stark separation, describing them as "two nations" with no understanding of each other's lives.

Working Conditions in Factories:

Factory work became the norm for many, characterized by long hours, low wages, monotonous tasks, and strict discipline enforced through supervision and fines.

The work environment was often harsh and insecure, influenced by the fluctuations of a capitalist economy.

Initially, factories preferred to employ young women and girls for certain tasks, as they were considered more docile and willing to accept lower wages.

Gender Dynamics in Industrial Work:

A gendered hierarchy in factories placed men in supervisory and skilled roles, while women were relegated to less skilled and lower-paying jobs.

Women were generally excluded from early labor unions, which began to provide men some influence over their working conditions.

Role of Women in the Laboring Classes:

Many women in the laboring classes worked in factories or as domestic servants for upper- and middle-class families, often to supplement family income.

After marriage, societal expectations generally dictated that women leave paid employment; however, many continued to contribute economically through home-based activities like laundry or sewing.

Working-class women juggled extensive domestic responsibilities with these economic activities, highlighting the dual burden of employment and domestic duties.

AP Question: How were the lives of the laboring masses negatively impacted by the Industrial Revolution?

Poor Living Conditions:

The rapid urbanization that accompanied industrialization led to overcrowded living environments. Cities lacked adequate sanitation, leading to frequent epidemics and poor public health.

Housing for the laboring masses was often in endless rows of cramped row houses with inadequate and polluted water supplies, contributing to a significantly lower quality of life.

Low Life Expectancy:

The harsh living conditions and inadequate healthcare in urban areas contributed to a decreased life expectancy. By 1850, the average life expectancy in England had dropped to 39.5 years, which was lower than it had been three centuries earlier.

Economic Insecurity and Exploitation:

Industrial work was characterized by long hours, low wages, and the routine and monotony of tasks dictated by factory schedules and machine requirements.

Child labor continued to be prevalent, and the entire family often needed to work under strenuous conditions just to survive.

The cyclical nature of the capitalist economy meant that industrial jobs were insecure, with frequent layoffs and no unemployment benefits, exacerbating the vulnerability of the working class.

Harsh Working Conditions:

Factory environments were strict and controlled, with constant supervision to enforce work discipline through rules and fines.

The repetitive and monotonous tasks in factories were a significant departure from the more varied and autonomous nature of artisanal or agricultural work that many laborers had previously known.

Gendered Labor Exploitation:

Women and young girls were often preferred as factory workers for certain tasks because they could be paid less and were perceived as more docile.

Despite their significant contributions to industrial production, women were often placed in lower-paying roles and were excluded from labor unions, which began to offer some protection and bargaining power to male workers.

Social Stratification:

The Industrial Revolution deepened the divide between the wealthy industrial capitalists and the laboring masses, with minimal interaction between the rich and the poor, leading to a lack of understanding and empathy for the working class's struggles.

Responses to Industrialization: Social Protest

Formation of Friendly Societies:

By 1815, approximately 1 million workers, mostly artisans, had established "friendly societies."

These self-help groups were funded by member dues and provided benefits like sickness insurance, funeral costs, and social engagement opportunities in the otherwise harsh industrial environment.

Resistance and Protests:

Skilled artisans displaced by industrial machines sometimes resorted to violent actions, such as destroying machinery and setting mills on fire, to protest their unemployment and the changes that threatened their livelihoods. This was notably seen in the actions of the Luddites.

Class consciousness among the working class was high, with widespread support for these actions both in urban and rural areas.

Political Involvement and Trade Unions:

The working class also sought political change, joining movements that advocated for extending voting rights to working-class men, which was gradually achieved later in the century.

Following the legalization of trade unions in 1824, a growing number of factory workers joined these groups, striving for better wages and working conditions. Despite initial fears and resistance from the upper classes, these organizations eventually gained a more respectable standing.

Spread of Socialist Ideas:

Socialist ideologies began to gain traction among the working class, challenging the capitalist system. Notably, Robert Owen, a wealthy manufacturer, proposed and implemented a model industrial community that offered better treatment for workers.

Karl Marx, a German thinker residing in England, provided a critical analysis of industrial capitalism, predicting its eventual collapse and the rise of a classless socialist society. His ideas influenced the formation of socialist movements across Europe.

Impact of Marxist Socialism:

Marx's concept of "scientific socialism" suggested that a socialist revolution was an inevitable outcome of historical developments, inspired by both the social conditions of industrialization and the precedents set by the French Revolution.

Socialist parties emerged in most European states, forming international organizations, participating in elections, and pushing for reforms while some factions considered more radical actions.

Evolution of Worker Movements and Social Democracy:

By the late nineteenth century, many worker movements in Britain and other industrializing nations adopted a non-revolutionary approach, focusing on reforms within the existing political systems. The British Labour Party, founded in the 1890s, advocated for a peaceful and democratic transition to socialism, distancing itself from the revolutionary tenets of Marxism.

Social democracy, which became prominent in Germany and later spread across Europe, emphasized reform and gradual improvement within capitalist societies rather than an outright overthrow of the system.

Improvements in Working-Class Conditions:

Despite Marx's expectations of increasing impoverishment, the working-class experience in capitalist societies improved somewhat by the end of the nineteenth century.

Increases in wages, better food accessibility, and improvements in public health and sanitation contributed to enhanced living conditions.

Political reforms, motivated by the extended voting rights to working-class men, led to legislative changes that benefitted workers, including the regulation of labor conditions and the introduction of unemployment relief.

Nationalism and Working-Class Radicalism

Impact of Nationalism:

As the twentieth century approached, a growing sense of nationalism began to influence the working classes, aligning their interests more closely with those of the middle-class and national elites rather than against them.

This sense of national identity helped to dampen some of the class antagonism that had been predicted by Marx, as workers felt a bond with their fellow countrymen, including those from different social classes.

World War I and Class Loyalty:

The outbreak of World War I demonstrated the powerful effect of nationalism on the working class. Contrary to Marx's hopes that workers would unite across national lines against bourgeois oppression, they instead rallied to their national flags.

The war saw workers fighting against each other, aligning with their national interests rather than forming a united front against the capitalist system, showing that national loyalty had overridden class solidarity.

Social and Economic Tensions in Early 20th Century Britain

Persistent Social Inequalities:

Despite the advancements and changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution, Britain as the twentieth century dawned was marked by significant social unrest and dissatisfaction.

About 40% of the working class still lived in what was recognized as poverty, highlighting the continued vast economic disparities within the society.

Labour Movements and Strikes:

The period from 1910 to 1913 witnessed a significant rise in labor unrest, with numerous strikes indicating strong and ongoing class conflict.

The Labour Party was gaining traction as a significant political force, reflecting the growing political influence of the working class and their demands for better conditions and rights.

Radicalization of Social Movements:

The early 1900s also saw an increase in the radicalization of various social groups, including some factions within the socialist and feminist movements.

Eric Hobsbawm's observation of "wisps of violence" in the air underscores the tensions and dissatisfaction that permeated English society, despite outward appearances of wealth and success.

Economic Decline Relative to Other Industrial Nations

Technological and Economic Stagnation:

Britain, which had been the pioneer of the Industrial Revolution, began to experience relative economic decline compared to newer industrial powers like Germany and the United States.

British businessmen had invested heavily in early industrial machinery, which by the turn of the century had become outdated. This commitment to older technology hindered Britain's ability to compete with nations that had adopted more modern and efficient equipment.

Global Industrial Realignment:

The shift in industrial dominance was evident as countries that had industrialized later than Britain took advantage of newer technologies and methods, surpassing Britain in various aspects of industrial and economic performance.

AP Questions:

How did the condition of the laboring classes lead to political reforms and the development of economic ideologies?

Drive for Political Reforms:

The harsh conditions faced by the laboring classes, including low wages, long hours, unsafe work environments, and poor living conditions, spurred movements demanding political change.

Labor unrest, such as strikes and protests, demonstrated the need for government intervention, leading to reforms like the establishment of labor laws, safety regulations in workplaces, and systems of relief for the unemployed.

Development of Economic Ideologies:

The plight of the working class under industrial capitalism provided fertile ground for the development and spread of alternative economic ideologies, notably socialism and Marxism.

Socialist ideas gained traction as they promised a more equitable distribution of resources and a society free from the exploitation inherent in the capitalist system. This was particularly appealing to workers experiencing the negative impacts of industrialization firsthand.

In what situations would the ideas of Karl Marx have the most appeal among the lower classes?

Economic Exploitation and Inequality:

Marx's ideas find strong resonance among the lower classes during periods of intense economic exploitation and stark inequalities where the wealth generated by workers disproportionately benefits the upper classes.

Situations where workers endure poor working conditions, low pay, and lack of job security, making the call for a classless society and the end of private property appealing.

Limited Social Mobility:

In societies where social mobility is restricted, and the class divides are rigid, making it difficult for individuals from lower economic backgrounds to improve their situations, Marxist critiques of capitalism can become particularly attractive.

Political Repression:

Marx's advocacy for revolutionary change tends to appeal to the lower classes in contexts of political repression, where peaceful and democratic means of reform appear ineffective or blocked by the ruling elites.

Explain how governments in Western Europe responded to Marx’s ideas.

Suppression and Surveillance:

Initially, many Western European governments responded to Marxist ideas with suppression, censoring socialist literature and monitoring or imprisoning its proponents to prevent the spread of revolutionary sentiment.

Integration of Social Policies:

Over time, as the labor movement grew stronger and more capable of organizing widespread protests, governments began to integrate some socialist principles into public policy. This included enacting labor laws, improving working conditions, and establishing social welfare programs to mitigate the inequalities highlighted by Marxists.

Adoption of Social Democratic Models:

In some countries, particularly in Scandinavia, the government response involved adopting social democratic models that combined market capitalism with extensive social welfare measures, aiming to address social inequalities while maintaining a capitalist economic framework.

How could nationalism lessen the potential for socialist revolutions in some countries?

Diversion of Class Conflict:

Nationalism can divert attention from class issues to national issues, uniting different classes against perceived external threats or in pursuit of national glory, thus diluting the class solidarity necessary for a socialist revolution.

Creation of Cross-Class Alliances:

By fostering a sense of national identity that transcends class boundaries, nationalism can lead to alliances between the working classes and the middle or upper classes, focusing on national interests rather than the class struggle.

Legitimization of State Power:

Nationalist sentiment often legitimizes the state's power and its military or economic ambitions, which can detract from revolutionary goals and reinforce the status quo.

Promotion of Reform Over Revolution:

In some contexts, nationalism encourages reformist approaches to social and economic issues as opposed to outright revolutionary changes, as the focus remains on national improvement within the existing state framework.