Chapter 6.1 World Commerce

Emergence of Global Trade

Emergence of Global Trade

Prelude to European Exploration

The exploration of Asia by Europeans, especially the Portuguese, was the result of detailed planning.

Portugal explored the sea route to Asia by moving down the West African coast, rounding the Cape of Good Hope at South Africa, and crossing the Indian Ocean to India.

Vasco da Gama's voyage from 1497 to 1499 was the first time Europeans sailed directly to India, showcasing this effort wasn't by chance but a strategic move.

Motivations for Exploration

Europeans were motivated to find a sea route to Asia mainly because of the desire for spices like cinnamon, nutmeg, mace, cloves, and pepper. These were used in food, as medicine, and for preservation.

There was also a high demand for luxury goods from Asia, including Chinese silk, Indian cotton, and precious stones such as emeralds, rubies, and sapphires.

Europe's Recovery and Growth

After the Black Death, Europe started to recover in the fifteenth century, with an increase in population and stronger national monarchies capable of taxing their people and building large armies.

Cities in England, the Netherlands, and Northern Italy grew as centers of international trade, leading to the development of economies based on market exchange, private ownership, and investment.

Challenges with Existing Trade Routes

Eastern goods reaching Europe had to pass through Muslim-controlled routes, with Venice controlling the trade into Europe. This setup was not favorable to emerging European powers.

Europeans were also inspired by the legend of Prester John, hoping to ally with his kingdom against Muslim traders.

Paying for Asian goods was a problem since Europe had to use gold or silver for trade, leading to a trade deficit.

European Entry into Asian Commerce

After Portugal, other European nations like Spain, France, the Netherlands, and Britain entered the Asian trade network, each employing different strategies but together impacting global trade.

This move was driven by the search for wealth, particularly from the spice trade, and the need to establish direct trading links with Asia to avoid relying on Venetian and Muslim intermediaries.

Impact of European Involvement in Asian Trade

By entering the Asian trade network, Europeans became part of a rich and extensive system of commerce that stretched from East Africa to China.

The European presence in Asian markets not only changed trade routes but also introduced new dynamics into the ancient trade system, altering global commerce significantly.

AP Analysis Questions:

What drove European involvement in the world of Asian commerce?

Desire for Spices and Luxury Goods: Europeans sought direct access to Asian spices like pepper, cinnamon, and cloves, which were in high demand for their use in food, medicine, and as preservatives, as well as luxury items like silk and precious stones.

Economic and Political Motivations: The drive to bypass Muslim and Venetian intermediaries controlling the spice trade motivated Europeans to find a direct sea route to Asia, aiming to break monopolies and control the trade themselves.

Technological Advances and Exploration: Improved navigation techniques and maritime technology, coupled with a spirit of exploration and the desire for wealth, fueled European ventures into Asian commerce.

Why was Europe just beginning to participate in global commerce during the sixteenth century?

Recovery from the Black Death: Europe's population and economies were recovering from the Black Death, leading to increased demand for goods and new markets.

National Monarchies and Military Capabilities: The rise of stronger national monarchies, capable of organizing large-scale voyages and exploiting new territories, played a crucial role in Europe's outward expansion.

Technological Innovations: Advances in navigation, shipbuilding, and weaponry during the Renaissance enabled Europeans to undertake long ocean voyages and engage in global commerce.

Why did Europeans control less territory in the Indian Ocean basin than they did in the Americas?

Existing Sophisticated Trade Networks: The Indian Ocean was home to an ancient and complex trade network involving powerful local states, making it difficult for Europeans to establish control.

Lack of Military Advantage: Unlike in the Americas, where Europeans had a clear military advantage over indigenous peoples, in the Indian Ocean basin, they faced well-armed and organized states, limiting their territorial conquests.

European Strategy and Presence: Europeans focused more on establishing trading posts and securing sea routes for commerce in the Indian Ocean rather than large-scale conquest that was their approach in the Americas.

The Portuguese Empire: Commerce

The Indian Ocean Commercial Network

The network was vast and diverse, involving East Africans, Arabs, Persians, Indians, Malays, Chinese, and others, with most traders being Muslims alongside Hindus, Buddhists, Christians, Jews, and Chinese.

The network was open for trading with piracy being an occasional issue, and no single power dominated after the Chinese fleet's withdrawal in the early fifteenth century.

Portuguese Entry and Strategy

The Portuguese found their goods crude and unattractive to Asian markets, realizing they couldn't compete economically.

They capitalized on their military advantage with ships equipped with cannons, unlike the generally unarmed merchant vessels in the Indian Ocean.

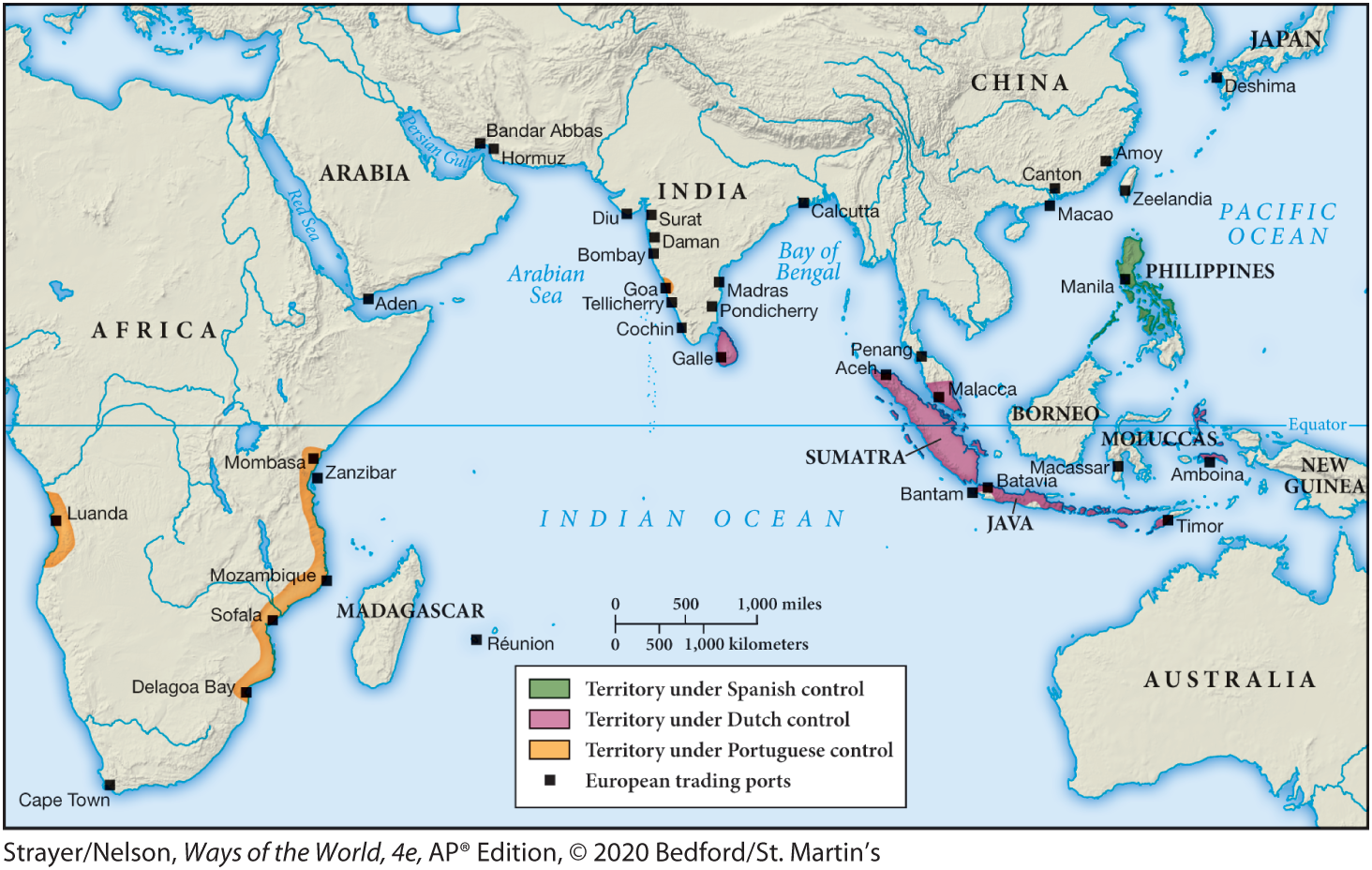

Portugal established fortified bases in strategic locations including Mombasa, Hormuz, Goa, Malacca, and Macao, often through force against weaker states, except for Macao which was obtained through negotiations.

Creation of a Trading Post Empire

Aimed to control commerce, not territories or populations, through force rather than economic competition.

The Portuguese king titled himself “Lord of the Conquest, Navigation, and Commerce of Ethiopia, Arabia, Persia, and India.”

They introduced a pass system (cartaz) for merchant vessels and imposed duties on cargoes, attempting to monopolize the spice trade and block traditional trade routes, though they never fully controlled the spice trade to Europe.

Assimilation and Decline

The Portuguese gradually integrated into the existing trade patterns, offering shipping services and marrying Asian women, as they were unable to sell their goods.

By 1600, the Portuguese empire was in decline due to overextension and resistance from rising Asian states and other European powers unwilling to accept Portuguese dominance in the spice trade.

Challenges and Resistance

Portugal faced resistance from local states and other European nations, leading to a gradual loss of control over the spice trade.

Asian states like Japan, Burma, Mughal India, Persia, and the sultanate of Oman actively resisted Portuguese efforts, marking a shift in power dynamics in the Indian Ocean.

AP Questions:

To what extent did the Portuguese realize their goals in the Indian Ocean?

Limited Monopoly and Commercial Control: The Portuguese aimed to establish a monopoly over the spice trade and control commerce through their trading post empire. They achieved this to a certain extent by forcing merchant vessels to buy a cartaz and pay duties, but they never fully controlled the spice trade, managing to dominate only about half of it to Europe.

Strategic Military Bases: They succeeded in setting up fortified bases in choke points like Mombasa, Hormuz, Goa, Malacca, and Macao. These bases, mostly obtained through military force, allowed Portugal to exert influence over key maritime routes and regional trade, though Macao was acquired through negotiations.

Military Advantages and Limitations: The Portuguese utilized their superior naval technology and onboard cannons to outmaneuver local naval forces and attack coastal cities. This military strategy enabled them to insert themselves into the Indian Ocean trade network, yet their crude and unattractive trade goods in Asian markets limited their economic competitiveness.

What are the factors that led to the decline of Portugal in the Indian Ocean trade network?

Economic and Military Overextension: Portugal's resources were stretched too thin across its global empire, making it difficult to sustain long-term control over its Indian Ocean bases and compete with rising local and European powers.

Increasing Resistance from Local and European Rivals: The emergence of powerful Asian states and active resistance against Portuguese control, combined with competition from other European powers keen on accessing the lucrative spice trade, significantly undermined Portuguese dominance.

Inability to Sustain Monopoly and Economic Competitiveness: Despite initial successes, Portugal could not maintain its monopolistic control over the spice trade, as traditional and alternative trade routes through the Ottoman Empire revived, diminishing Portugal's influence.

Compare the Europeans' interactions in the Indian Ocean trade network with their interactions in the trade network of the Americas.

Forced Economic Prescence vs. Broad Conquest: In the Indian Ocean, Portugal leveraged its military technology for strategic control and forced trade advantages without seeking broad territorial conquest, focusing on a network of fortified trading posts. In contrast, in the Americas, European powers pursued extensive territorial conquests, subjugating and often decimating indigenous populations to exploit the continents' resources directly.

Integration into Existing Trade Networks vs. Establishment of New Economies: The Portuguese integrated into the Indian Ocean trade network, adapting to its ancient patterns and marrying into local populations. In the Americas, Europeans established new colonial economies, often replacing indigenous economic systems with European agricultural and mining enterprises.

Economic Participation vs. Economic Domination: In the Indian Ocean, the Portuguese became one of many participants in a diverse trading culture, eventually engaging in the "carrying trade" due to their inability to compete with Asian goods. In the Americas, Europeans dominated economic systems, controlling trade and extracting wealth through direct rule and the imposition of European economic models.

Spain and the Philippines

Initial Encounter and Conquest

The Spanish targeted the Philippine Islands for expansion, finding an archipelago with diverse cultures and small, competing chiefdoms. China and Japan, the major regional powers, showed little interest in these islands.

The Spanish conquest, starting in 1565, was executed with military operations, alliances with local chiefs, and Catholic rituals, leading to a relatively peaceful Spanish control over the islands.

Religious Conversion and Conflict

Spanish rule introduced an extensive missionary effort that converted the majority of the Filipino society to Christianity, marking the Philippines as a significant Christian community in Asia.

Islam, strengthening in the southern island of Mindanao, provided a basis for resistance against Spanish rule, a conflict persisting into the twenty-first century.

Colonial Practices and Social Changes

Spanish colonial methods included relocating people into concentrated Christian communities, and implementing tribute, taxes, and forced labor. Large estates were established, owned by Spanish settlers, Catholic orders, or local elites.

Women, previously influential as ritual specialists and healers, were displaced by male Spanish priests, leading to the loss of their traditional roles.

Manila: Capital and Cultural Hub

Manila evolved into a prosperous city by 1600, with a population over 40,000, including Spanish officials, Filipino migrants, and significant Japanese and Chinese communities.

The Chinese, crucial for their roles in trade and craftsmanship, faced discrimination and hostility from the Spanish, resulting in periodic revolts and severe repressions, including a massacre in 1603 that killed about 20,000 Chinese residents.

AP Questions:

How did the goals and actions of the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, and British in Asia differ?

Portuguese: Aimed to establish a trading post empire to control key maritime routes and monopolize the spice trade, utilizing military force to establish fortified bases in strategic locations without seeking to control large territories or populations.

Spanish: Sought to establish outright colonial rule, as seen in the Philippines, focusing on converting the population to Christianity and integrating the islands into their colonial empire, rather than just controlling trade.

Dutch and British: Focused on establishing their own trading companies (the Dutch East India Company and the British East India Company, respectively) to control trade through both economic dominance and military force. They were more interested in direct control over specific territories and resources critical to their trade interests, eventually leading to extensive colonial rule in certain areas.

What were Spain’s reasons for colonizing the Philippines?

Strategic Location: The Philippines' proximity to China and the Spice Islands made it a valuable base for trade within Asia and with the Americas.

Military and Political Advantage: The small, militarily weak societies and the absence of competing claims from other major powers allowed Spain to easily establish control.

Religious Motivation: A significant part of Spain's interest was the conversion of the Filipino population to Christianity, aiming to create a major outpost of Christianity in Asia and counter Islamic expansion in the region.

The East India Companies: Dutch and British Competition

Introduction of Dutch and English in Indian Ocean Commerce

By the early seventeenth century, the Dutch and English emerged as significant competitors in the Indian Ocean, quickly surpassing Portuguese dominance through military force and mutual competition.

By the sixteenth century, the Dutch had developed a highly commercialized and urbanized society, excelling in maritime operations and business skills, admired across Europe.

Formation of Trading Companies

Unlike the Portuguese, both the British and Dutch structured their Indian Ocean activities around private companies: the British East India Company and the Dutch East India Company, established around 1600.

These companies received charters from their governments granting them trading monopolies and the authority to wage war and govern territories, leading to the creation of separate trading post empires: the Dutch in Indonesia and the English in India.

A French company also entered the Indian Ocean trade in 1664, adding to the European competition.

Dutch East India Company

Establishment and Objectives

The Dutch East India Company was established in the early seventeenth century, structured around a government-granted charter that provided it with trading monopolies and the authority to wage war and govern territories.

Aimed to dominate the spice trade by controlling both the shipping and production of key spices such as cloves, cinnamon, nutmeg, and mace.

Strategies for Spice Trade Dominance

Engaged in aggressive tactics to monopolize spice production, involving the seizure of small spice-producing islands and the use of force to compel local producers to sell only to the Dutch.

Employed violence to maintain control, notably in the Banda Islands, where the Dutch decimated the local population, replacing them with Dutch planters and using slaves from other parts of Asia for labor.

Economic Impact and Monopoly

Achieved a temporary monopoly in the seventeenth century on spices like nutmeg, mace, and cloves, selling these at significantly higher prices in Europe and India compared to what they paid in Indonesia.

The monopoly led to substantial profits for the Dutch but had a devastating impact on the local economy of the Spice Islands, leading to impoverishment and social disruption.

Transition Towards Colonial Rule

The Dutch East India Company's trading post empire gradually evolved into a more conventional form of colonial domination over Indonesia by the late eighteenth century.

This transition marked a significant shift from purely commercial operations to direct governance and control over territories and populations.

British East India Company

Establishment and Approach

The British East India Company was formed around 1600, similarly organized through a charter that granted it trading monopolies, the power to wage war, and authority over conquered territories, but operated with less financial strength and commercial sophistication than its Dutch counterpart.

Focused primarily on India after being largely excluded from the lucrative Spice Islands due to the Dutch monopoly.

Trading Settlements and Strategy in India

Established key trading bases in Bombay (now Mumbai), Calcutta, and Madras through agreements, involving substantial payments and negotiations with Mughal authorities or local rulers, rather than the Dutch method of direct control through violence.

Unable to employ "trade by warfare" due to the powerful presence of the Mughal Empire, the British sought permissions for trade rather than conquering territories.

Shift in Trade Focus

Although initially interested in spices, British trade increasingly centered on Indian cotton textiles, which were in high demand in England and its American colonies.

Integrated hundreds of villages in southern India into their production network for this market, marking a significant shift from spice to textiles in their commercial priorities.

Naval Dominance and Merchant Operations

British naval forces gained control over the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf, replacing Portuguese dominance in these waters, which facilitated their trade routes to and from India.

Despite focusing on peaceful trade and negotiations, the British East India Company faced challenges, such as when independent English traders' actions against a Mughal ship led to detentions and a large fine, highlighting the precarious nature of their presence in India.

Evolution Towards Colonial Domination

By the second half of the eighteenth century, the British East India Company's role in India transitioned from commercial operations to direct colonial rule, marking the beginning of British governance over India.

This shift involved not only economic dominance but also administrative control and the introduction of British legal and educational systems.

AP Questions:

To what extent did the British and Dutch trading companies change the societies they encountered in Asia?

Economic Disruption and Dependency: The British and Dutch companies drastically altered local economies, especially in the Spice Islands and India. The Dutch monopolized spice production, impoverishing local societies, while the British integrated Indian textile production into global markets, shifting local economies towards dependency on European demand.

Societal and Demographic Changes: In areas like the Banda Islands, the Dutch eradicated or enslaved the local population, replacing them with Dutch planters and Asian slaves. This led to significant demographic changes and the displacement of indigenous societies.

Cultural and Administrative Influence: Both the Dutch in Indonesia and the British in India introduced European administrative practices, legal systems, and educational methods, significantly affecting local cultures and societies. They also imposed new social hierarchies that prioritized Europeans and aligned local elites with their rule.

What were the political and economic roles of Europe's East India companies?

Economic Expansion and Monopoly Control: The British and Dutch East India Companies were instrumental in expanding European economic interests in Asia, securing monopolies over crucial commodities like spices and textiles. They directed the flow of goods between Asia and Europe, significantly impacting global trade patterns.

Semi-autonomous Governance: Both companies functioned as semi-autonomous entities with the power to wage war, negotiate treaties, and govern territories. They acted as extensions of their respective governments in Asia, wielding significant political and military power.

Strategic and Military Engagement: The companies played strategic roles in establishing and defending European interests in Asia. They built fortified trading posts, maintained private armies, and engaged in military conflicts with both European rivals and local powers to protect and expand their trade networks.

How did Europeans view themselves in their trade relationship with Asian societies?

Perception of Superiority: The British and Dutch viewed themselves as superior, partly due to their advanced maritime technology and military capabilities. This perceived superiority justified their dominance over trade routes and imposition of trade terms.

Agents of Economic and Cultural Advancement: They saw themselves as bringing economic opportunity and cultural advancement to Asia, introducing efficient governance, modern technologies, and Christianity, overlooking the often destructive impact of their actions on local societies.

Competitive Dominance: In their trade relationships with Asian societies, the British and Dutch considered themselves as rightful competitors striving for dominance in global commerce. They believed their involvement was essential for securing national interests and establishing a global trading network centered on European powers.

Asians and Asian Commerce

Limited European Control in Asia

Europeans had significantly less political control in Asia compared to the Americas or Africa, with their control mostly limited to the Philippines, parts of Java, and a few Spice Islands.

The Southeast Asian state of Siam expelled French forces in 1688 due to aggressive conversion efforts and political interference, highlighting European challenges in establishing dominance.

Major Asian Powers and European Presence

In major Asian powers like Mughal India, China, and Japan, Europeans posed no real military threat and played minor roles economically, contrasting with their significant impact in other regions.

Japan's Management of European Influence

Portugal, Spain, Dutch, and English traders and missionaries initially found Japan welcoming due to internal conflicts among feudal lords (daimyo) and interest in European military technology and ideas.

A Christian movement gained traction in Japan in the late sixteenth century, leading to the conversion of approximately 300,000 Japanese and the formation of a Japanese-led church organization.

The Tokugawa Shogunate’s Unification of Japan and Suppression of Christianity

By the early seventeenth century, Japan was politically unified under the shogunate leadership of the Tokugawa clan (Or just the Tokugawa Shogunate), leading to a shift in perspective on Europeans from opportunities to threats.

Christian missionaries were expelled, and Christianity was violently suppressed, including the execution of missionaries and Japanese converts, marking a significant religious and political stance against European influence.

Tokugawa Shogunate's Isolationist Policies

The Tokugawa shogunate implemented policies to close Japan off from European commerce, except for the Dutch, who were allowed limited trade. This was a strategic withdrawal from European influences while maintaining regional trade ties.

Japanese and Other Asian Merchants' Role in Southeast Asia

Japanese traders operated independently in Southeast Asia, often using force in commercial pursuits without official support from the Tokugawa shogunate, indicating a distinct approach compared to European state-backed merchants.

Despite European naval dominance, Asian merchants, including Arab, Indian, Chinese, and Southeast Asian, continued to thrive in the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asian trade, demonstrating resilience and adaptation to changing trade dynamics.

Asian Commercial Networks and European Interaction

Asian merchants dominated overland trade and maintained sophisticated commercial networks, engaging in extensive trade within Asia and with Europe, without being overshadowed by European activities.

In India, large family firms managed to monopolize trade in specific commodities, dictating terms to European companies and highlighting the continued strength and influence of local economic powers in the face of European presence.

AP Questions:

In what ways did Asian political authority and economic activity persist in the face of European intrusion?

Maintenance of Sovereignty: Major Asian powers like Qing China and Tokugawa Japan maintained their political sovereignty by either limiting European trade to specific ports under strict regulations or by adopting policies that minimized European influence on their internal affairs.

Economic Independence: Despite European naval dominance, Asian economies, particularly China and Japan, continued to thrive, engaging in trade within Asia and maintaining extensive trade networks with or without European participation. In China, the government regulated trade through the Canton System, while Japan, under the Tokugawa shogunate, allowed limited Dutch trade in Nagasaki.

Cultural and Social Continuity: Both China and Japan preserved their cultural and social structures. In China, the Confucian social hierarchy persisted, while in Japan, the social structure centered around the samurai and daimyo remained intact, ensuring stability and continuity despite European presence.

What were the roles of the samurai and the daimyo during the Tokugawa Shogunate?

Military and Administrative Functions: The samurai served as both warriors and bureaucrats during the Tokugawa period. They were responsible for maintaining order, collecting taxes, and administering justice within their domains or as officials in the shogunate government.

Governance of Territories: The daimyo were powerful feudal lords who ruled vast territories across Japan. They governed their lands semi-autonomously, provided military support to the shogunate, and were key figures in the political structure of Tokugawa Japan, balancing their power with the central authority of the shogun.

Cultural Patronage: Both samurai and daimyo were also important patrons of the arts and education, contributing to the cultural development of Japan during the Edo period. They supported activities such as tea ceremonies, Noh theatre, and the study of Confucian and Buddhist texts.

Describe the interactions between Japan and European traders in this era.

Initial Welcome and Utilization: European traders and missionaries, arriving in Japan in the mid-sixteenth century, were initially welcomed for their military technology, shipbuilding skills, and new religious ideas. Their goods and knowledge proved useful amidst Japan's internal conflicts among feudal lords.

Christianity's Growth and Subsequent Suppression: The introduction of Christianity led to a significant number of Japanese converts and the establishment of a Japanese-led Christian church. However, as Japan unified under Tokugawa rule, Christianity was viewed as a threat, leading to the expulsion of missionaries and suppression of Christian practices.

Restricted European Trade: By the early seventeenth century, Japan limited European interaction, allowing only Dutch traders to operate in Nagasaki under strict conditions, effectively isolating Japan from European influence while maintaining controlled trade relations.