Chapter 7.2 Afro-Eurasian Cultural Developments

Afro-Eurasian Global Religious Transformations, in the Early Modern Era.

African Religious Influence in the Americas

Transmission of African Religions: African slaves brought their religious practices to the Americas, including divination, dream interpretation, visions, and spirit possession.

Syncretic Religions: New religious forms such as Vodou in Haiti, Santeria in Cuba, and Candomblé and Macumba in Brazil emerged, blending African religious traditions with Christianity.

European Response: Although European colonizers often tried to suppress these practices as sorcery or witchcraft, they persisted and integrated elements of Christian worship like church attendance and the veneration of Catholic saints.

Expansion of Islam in the Afro-Asian World

Continued Spread of Islam: The "long march of Islam" continued across sub-Saharan Africa, India, and Southeast Asia, often integrating rather than replacing local religious practices.

Role of Muslim Clergy and Traders: Muslim holy men (Sufis), scholars, and traders facilitated the spread of Islam through non-confrontational means such as education, intermarriage, and offering services valuable to local rulers and communities.

Cultural and Religious Assimilation: Conversion to Islam often involved adopting Islamic rituals and cosmologies into local religious systems, enhancing rather than erasing existing beliefs.

Islamization Dynamics

Non-Military Spread: Unlike many historical instances of religious spread, Islamization during this period typically did not involve conquering armies but was carried out by non-threatening figures like traders and holy men who integrated into local societies.

Benefits of Islamic Connection: Converts gained access to the literate, prestigious, and economically prosperous world of Islam, which included benefits like literacy in Arabic and connections to wider trade networks.

Modest Spread to the Americas: Islam also made inroads into the Americas, notably in Brazil, where Muslim slaves influenced by Islamic teachings participated in revolts during the early nineteenth century.

Religious Diversity in Southeast Asia

Islamic Practices in Aceh: In the sultanate of Aceh, efforts were made to enforce Islamic dietary codes and almsgiving practices, reflecting a stricter adherence to Islamic law.

Gender and Power: The region experienced shifts in gender dynamics; after a period of female rulers, women were eventually barred from political power in Aceh, whereas in other parts of Indonesia, women continued to hold significant roles in society and the economy.

Coexistence of Beliefs on Java: In Java and throughout Indonesia, a more tolerant and accommodating form of Islam allowed the coexistence of traditional animistic practices with Islamic beliefs, showing the adaptability and flexibility of religious practice in the region.

Context of Islamic Renewal Movements

Orthodox Reactions: Throughout the 18th century, orthodox Muslims viewed religious syncretism as offensive and heretical, leading to movements aimed at purifying Islam from these perceived corruptions.

Criticism of Practices: Leaders of these movements criticized practices that had deviated from the teachings established by Muhammad and the Quran, targeting both localized religious practices and the rulers who tolerated or promoted such deviations.

Specific Examples of Reform Movements

Mughal Empire: During Emperor Aurangzeb's reign, there was a significant push against the empire's relatively tolerant religious policies that accommodated Hindu customs. Aurangzeb enforced stricter Islamic practices, reflecting broader Islamic revivalism.

West Africa: A series of religious wars aimed at purging corrupt Islamic practices and the rulers, both Muslim and non-Muslim, who permitted them. These conflicts were part of a larger movement to return to more orthodox Islamic values.

Southeast and Central Asia: Tensions grew between practitioners of localized, blended versions of Islam and those advocating for a return to orthodox practices, often leading to social and religious conflicts.

Emergence of Wahhabism in Arabia

Muhammad Ibn Abd al-Wahhab: He argued that the difficulties faced by the Islamic world, such as the weakening of the Ottoman Empire, were due to deviations from the pure faith of early Islam. He was particularly critical of practices like the veneration of Sufi saints and their tombs, which he saw as idolatrous.

Alliance with Muhammad Ibn Saud: In the 1740s, al-Wahhab gained the support of the local ruler Ibn Saud, and together they formed a political and religious movement that sought to enforce orthodox Islamic practices in central Arabia.

Implementation of Wahhabi Teachings

Enforcement of Orthodoxy: The Wahhabi movement, backed by Ibn Saud, implemented strict religious orthodoxy in central Arabia, including the destruction of tombs considered idolatrous, the banning of books on logic, and the prohibition of tobacco, hashish, and musical instruments.

Major Islamic movement led by the Muslim theologian Muhammad Ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703–1792) that advocated an austere lifestyle and strict adherence to the Islamic law; became an expansive state in central Arabia.

Tax Reforms: The movement also abolished certain taxes that were not authorized by Islamic teachings, aligning fiscal policies with religious laws.

Impact on Women's Rights Under Wahhabism

Women's Rights: Al-Wahhab emphasized women's rights within an Islamic framework, including the right to consent to marriage, control dowries, divorce, and engage in commerce. These rights, embedded in Islamic law, were highlighted as being neglected in contemporary practices.

Public Behavior and Dress: Contrary to later associations of Wahhabism with severe restrictions on women, al-Wahhab did not insist on complete covering for women in public and allowed for the mixing of unrelated men and women for practical reasons like business or medical purposes.

Expansion and Legacy of Wahhabism

Control Over Mecca: By the early 19th century, Wahhabi Islam had expanded to control significant territories in Arabia, including the holy city of Mecca, captured in 1803.

Suppression and Continued Influence: Although an Egyptian army defeated the Wahhabi state in 1818, the ideological and religious influence of Wahhabism continued to spread across the Islamic world, marking a significant period of Islamic revival and reform.

AP Questions

What accounts for the continued spread of Islam in the early modern era and for the emergence of reform or renewal movements within the Islamic world?

Spread through Trade and Diplomacy:

Trade Routes: The expansion of Islam continued through established trade routes across Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, where Muslim traders and merchants played a key role in disseminating Islamic practices and beliefs.

Cultural Exchanges: Diplomatic and cultural interactions between Islamic and non-Islamic states facilitated the spread of Islam beyond traditional boundaries, enhancing its global presence.

Role of Religious Figures:

Sufis and Scholars: Sufi missionaries and Islamic scholars were instrumental in spreading Islam peacefully by integrating Islamic teachings with local customs and traditions, making the religion more accessible and acceptable to diverse populations.

Community Services: These figures often provided valuable services such as education, legal advice, and medical care, which helped to embed Islamic practices within local communities.

Emergence of Reform Movements:

Response to Syncretism: The emergence of reform and renewal movements was largely a reaction against the syncretism observed in newly converted regions, where Islamic practices were being blended with indigenous beliefs.

Desire for Purification: Reformers sought to purify Islam by returning to the practices and teachings directly attributed to Muhammad and the Quran, opposing innovations and perceived deviations.

Explain how Islam changed as it spread.

Adaptation to Local Cultures:

Cultural Integration: As Islam spread, it adapted to local customs and traditions, which led to variations in practice and interpretation. This often resulted in a more culturally integrated form of Islam that differed significantly from its origin.

Syncretic Practices: In many areas, Islamic rituals and beliefs merged with local religious practices, creating unique syncretic forms of Islam that reflected both Islamic teachings and indigenous traditions.

Development of Sects and Schools of Thought:

Sectarian Developments: The spread of Islam also led to the development of different sects and schools of thought, each interpreting the core teachings of Islam according to regional and cultural contexts. This diversity within Islam reflects its adaptability and broad appeal.

Jurisprudential Differences: Differences in Islamic jurisprudence emerged, influenced by local customs and philosophical inquiries, leading to the establishment of various legal schools that catered to the needs of different Islamic communities.

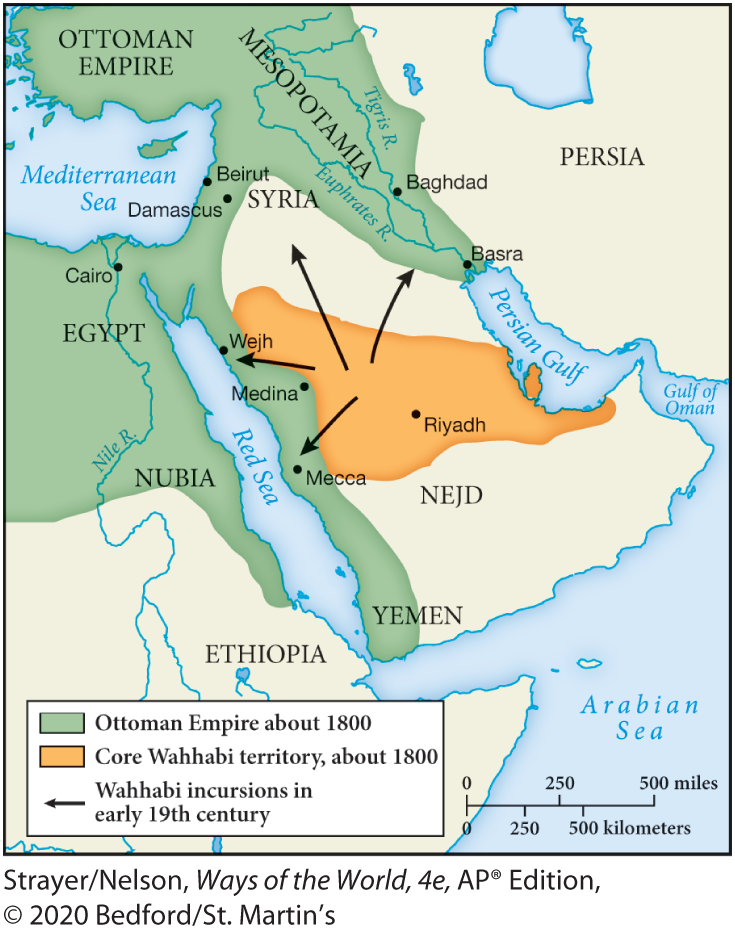

How did the spread of the Wahhabi movement displayed in the map influence the practice of Islam in Arabia?

Enforcement of Orthodoxy:

Strict Adherence to Monotheism: The Wahhabi movement, with its strict interpretation of monotheism, sought to eliminate practices it deemed polytheistic, such as the veneration of saints, the use of charms, and the celebration of local festivals that included idolatrous customs.

Destruction of Shrines: Wahhabism led to the physical destruction of shrines and other religious sites associated with practices considered un-Islamic, drastically altering the religious landscape of Arabia.

Legal and Social Reforms:

Implementation of Sharia: Wahhabism emphasized the strict application of Sharia, leading to significant changes in legal and social practices within the regions it controlled. This included reforms in areas such as criminal justice, marital law, and public behavior.

Influence on Daily Life: Daily life in Wahhabi-controlled areas saw a reduction in practices such as the consumption of tobacco and the playing of music, which were viewed as un-Islamic by Wahhabi standards.

Long-Term Influence:

Foundation for Saudi Arabia: The alliance between Muhammad Ibn Saud and Muhammad Ibn Abd al-Wahhab laid the foundations for the modern state of Saudi Arabia, influencing the religious, political, and social framework of the region.

Global Impact: The principles of Wahhabism have had a lasting impact on global Islam, influencing contemporary Islamic movements and shaping debates within the Muslim world about the nature of true Islamic practice.

Chinese Cultural Developments

Overview

Stability in Change: While China and India did not experience as dramatic cultural or religious transformations as Europe or Arabia, they did see significant intellectual and cultural shifts during the early modern period.

Continued Influence of Traditional Systems: Both regions continued to operate broadly within their traditional religious and philosophical frameworks, Confucianism in China and Hinduism in India, though these were not static and adapted over time.

Developments in China

Neo-Confucianism: Before the Ming and Qing dynasties, Confucianism absorbed elements of Buddhism and Daoism, which helped in the generation and popularization of Neo-Confucianism during the Song Dynasty.

Support for Confucianism: Ming rulers promoted Confucianism to distance themselves from the Mongol rule, while the Qing dynasty used it to gain the support of Chinese intellectuals.

Intellectual Movements and Thinkers

Wang Yangming's Teachings: Influential during the late Ming period, Wang Yangming proposed that intuitive moral knowledge was inherent in all people, suggesting that virtuous life could be achieved through introspection and moral contemplation without extensive classical education.

His ideas introduced a form of moral individualism similar to Martin Luther's religious individualism in Europe.

Kaozheng Movement: This scholarly approach emerged in late Ming and continued into the Qing era, focusing on "research based on evidence" and emphasizing verification and precision in various fields such as agriculture, medicine, and historical scholarship.

It represented a scientific approach, though primarily applied to historical and textual criticism rather than natural sciences.

Cultural Expression and Popular Culture

Rise of Popular Culture in Cities: In urban areas, a lively popular culture emerged, characterized by plays, paintings, short stories, and novels that catered to the entertainment needs of the city-dwellers, distinct from the elite intellectual pursuits.

Expansion of the Printing Industry: A robust printing industry developed in response to growing public demand for literature, particularly novels which became increasingly popular among the broader populace.

The Dream of the Red Chamber: One of the most famous novels of the period, written by Cao Xueqin in the mid-18th century, this work explored the intricate social life of an elite family and offered insights into the complexities of Chinese society, reflecting broader cultural themes and the sophistication of Chinese literary culture.

Summary

Intellectual and Cultural Dynamism: The early modern era in China was marked by significant intellectual debate, cultural flourishing, and the evolution of traditional philosophical systems. These developments reflected a society that was simultaneously deeply rooted in its historical traditions and dynamically engaging with new ideas and social changes.

Continuity and Adaptation: Despite the lack of dramatic religious reformations or revolutions, both China and India demonstrated a capacity for cultural and intellectual evolution that responded to changing social, political, and economic conditions without the overthrow of their foundational cultural systems.

AP Questions:

What kinds of cultural changes occurred in China and India during the early modern era?

Intellectual Developments:

China: The period saw the emergence of Neo-Confucianism, which incorporated elements from Buddhism and Daoism, enriching the Confucian framework with broader philosophical insights. Intellectual movements like the kaozheng, focusing on evidence-based research, brought a more scientific approach to scholarship.

India: While less dramatic than in China, India also experienced cultural and religious ferment, with various movements within Hinduism and Islam adapting to changing social and economic conditions, and the influence of European colonial presence beginning to make its impact felt.

Expansion of Literature and the Arts:

China: A vibrant popular culture developed in urban centers, with an increase in the production and consumption of novels, plays, and paintings. The famous novel "The Dream of the Red Chamber" exemplified this trend, offering deep insights into Chinese society and its values.

India: Similar cultural developments occurred, though often intertwined with religious themes. The spread of various artistic styles and the patronage of arts by rulers like those in the Mughal Empire encouraged a synthesis of indigenous and Persian influences, which was reflected in architecture, painting, and literature.

Social and Economic Changes:

China: The growth of urban centers and the expansion of commerce had a transformative impact on social structures, leading to a more dynamic interaction between different social classes and a flourishing of urban culture.

India: Economic changes, particularly those brought about by the growing impact of European trade and later colonial rule, began to alter traditional structures and practices, leading to shifts in social hierarchies and the roles of various classes within society.

How did Neo-Confucianism differ from traditional Confucianism?

Philosophical Integration:

Incorporation of Buddhism and Daoism: Neo-Confucianism, which developed during the Song dynasty and continued into the Ming and Qing dynasties, integrated metaphysical and ethical ideas from Buddhism and Daoism into the Confucian framework. This synthesis aimed to address spiritual and existential questions that were less emphasized in earlier Confucian thought.

Ethical and Moral Emphasis:

Focus on Innate Morality: Neo-Confucianism placed a greater emphasis on the inherent moral sense within individuals, a concept that was advanced by thinkers like Wang Yangming, who argued that intuitive moral knowledge exists in all people. This was a shift from the earlier Confucian focus on ritual, hierarchy, and external conduct toward a more internalized sense of virtue.

Rational Inquiry and Empiricism:

Kaozheng Movement: Associated with Neo-Confucianism, the kaozheng movement emphasized rigorous empirical research and critical analysis, particularly in historical study. This marked a departure from the more traditional Confucian reliance on classical texts and commentaries, moving towards a methodology that valued evidence and precision in scholarly pursuits.

Social Impact:

Broadening of Educational Focus: While traditional Confucianism emphasized education primarily for the elite class of scholars and bureaucrats, Neo-Confucianism, through its broader philosophical scope, began to influence a wider segment of society, reflecting the changing social dynamics of the time.

India: Muslims and Hindu Interactions in the Mughal Empire

Mughal Influence on Hindu-Muslim Cultural Exchange

Akbar's Religious Integration Efforts: Mughal Emperor Akbar attempted to integrate elements of Islam, Hinduism, and Zoroastrianism into a unique state cult, reflecting his broader policy of religious tolerance and synthesis aimed at unifying his diverse subjects.

Cultural Patronage at Mughal Court: The Mughal court under Akbar and his successors actively engaged with and patronized Renaissance Christian art, integrating Christian iconography into palace murals and other architectural elements, symbolizing a broader acceptance and appreciation of different religious aesthetics.

Sufi-Hindu Collaborative Works: A notable project involved a Sufi master creating an illustrated guide to Hindu yoga practices, known as the Ocean of Life, which presented yogic postures through a Sufi interpretive lens, aiming to harmonize elements of both traditions.

Bhakti Movement's Role in Social and Religious Transformation

Growth and Appeal of Bhakti: The bhakti movement gained significant traction in Hindu communities by promoting a personal, devotional approach to spirituality that transcended orthodox rituals and caste barriers, thereby appealing to a broad spectrum of society including women and lower castes.

Challenging Orthodox Hindu Practices: Bhakti adherents often criticized and disregarded the rigid rituals and caste distinctions enforced by Brahmin priests, advocating for a more inclusive and personal spiritual experience.

Intersections with Islamic Sufism: The mystical aspects of the bhakti movement resonated with similar themes in Sufism, particularly the emphasis on personal connection with the divine. This shared mystical dimension facilitated cultural exchanges and mutual respect between followers of Hinduism and Islam, softening religious boundaries.

Influential Figures in the Bhakti Movement

Mirabai’s Legacy: Mirabai, one of the most celebrated poets of the bhakti tradition, defied traditional gender and caste expectations by rejecting widow immolation (sati) and embracing a life devoted to the deity Krishna. Her poems express deep personal devotion and challenge societal norms, making her an icon of bhakti spirituality and female agency.

Social and Religious Impact: Mirabai's interactions with lower-caste individuals, such as her guru, an untouchable shoemaker, and her practices such as drinking the wash water of her guru’s feet, were radical acts that challenged social hierarchies and promoted spiritual egalitarianism.

Sikhism: Formation and Development of a New Religious Tradition

Origins and Teachings of Guru Nanak: Sikhism, founded by Guru Nanak, emerged from the rich religious landscape of the Punjab region, drawing on both bhakti and Sufi ideas. Nanak advocated a message of universal godliness that transcended traditional Hindu and Muslim identities, emphasizing a direct connection with God beyond religious labels.

Evolution into a Distinct Community: Over successive generations, Sikhism evolved from a spiritual movement into a well-defined religious community with its own scriptures (Guru Granth Sahib), symbols (such as uncut hair, turbans, and the kirpan), and a central place of worship (the Golden Temple in Amritsar).

Sikh Militancy and Identity: In response to external pressures and conflicts with both Mughal and Hindu authorities, Sikhism developed a militant aspect, which was crucial for its survival and eventual recognition as a significant martial group by the British colonial powers.

Broader Implications of Religious and Cultural Dynamics in India

Cultural Syncretism: The early modern period in India was marked by significant cultural syncretism, where religious and cultural traditions from Hinduism, Islam, and other influences intermingled, leading to rich and diverse expressions of spirituality and community life.

Impact on Indian Society: These movements and the figures associated with them played pivotal roles in shaping Indian society, challenging existing social structures, promoting new forms of religious expression, and paving the way for future social reforms.

AP Questions

Describe the attempts to connect Hindu and Muslim beliefs in South Asia in this era.

Akbar's Syncretic Policies:

Religious Integration: Emperor Akbar attempted to create a syncretic religious culture by promoting a state cult that blended elements from Islam, Hinduism, and Zoroastrianism. This was part of his broader policy of religious tolerance aimed at stabilizing and unifying his diverse empire.

Cultural Patronage: Akbar's court also embraced Christian and other religious artistic influences, incorporating them into the Mughal architectural and artistic repertoire.

Bhakti and Sufi Movements:

Common Mystical Themes: Both the Hindu Bhakti movement and Islamic Sufism emphasized personal devotion and a direct experience of the divine, which resonated across religious boundaries and facilitated mutual appreciation and cultural exchange.

Shared Devotional Practices: Devotional music, poetry, and dance forms from both traditions highlighted shared values of love and divine connection, fostering a sense of spiritual kinship among adherents.

How was the role of Guru Nanak similar to the role Martin Luther played in the Reformation?

Challenging Established Religious Practices:

Guru Nanak: He challenged the ritualistic and hierarchical structures of Hinduism and the perceived legalism in Islam, advocating for a more personal and direct relationship with God.

Martin Luther: Similarly, Luther challenged the Catholic Church’s practices and doctrines, advocating for "faith alone" as the means to salvation, and opposed the authoritative role of priests in mediating between God and believers.

Founding New Religious Movements:

Guru Nanak: Founded Sikhism, which broke away from the prevailing religious structures and emphasized equality and unity beyond traditional Hindu and Muslim identities.

Martin Luther: His teachings led to the establishment of Protestantism, which rejected many of the traditions of the Roman Catholic Church and promoted the Bible as the sole authority.

What caused the cultural changes that took place in India during the early modern period?

Mughal Influence:

Political Stability and Patronage: The consolidation of the Mughal Empire under rulers like Akbar created a stable environment that allowed for cultural and artistic flourishing, along with religious experimentation.

Interactions with Diverse Cultures: The Mughals facilitated cultural exchanges with other parts of the world, which brought new artistic and religious ideas into India.

Economic and Social Shifts:

Urbanization and Commercialization: Growth in commerce and the rise of urban centers during this period led to greater social mobility and the emergence of new social groups, which contributed to cultural dynamism and change.

What features of Sikhism created a distinct religious community?

Unique Theological Foundations:

Monotheism and Universal Godliness: Sikhism’s emphasis on a singular, formless God who transcends religious labels helped define its distinct theological identity.

Community and Equality:

Rejection of Caste: Sikhism explicitly rejected the caste system and promoted the equality of all humans, setting it apart from many traditional South Asian religious practices.

Role of the Guru Granth Sahib: The establishment of the Guru Granth Sahib as the eternal guru and central religious text provided a unifying and authoritative scripture for the community.

Cultural and Symbolic Practices:

Five Ks: The adoption of specific articles of faith, including uncut hair, a wooden comb, special undergarments, an iron bracelet, and a ceremonial sword, helped solidify community identity and commitment.

In what ways did religious changes in Asia and the Middle East parallel those in Europe, and in what ways were they different?

Parallels:

Reform Movements: Like Europe’s Protestant Reformation, both Asia and the Middle East saw movements aiming to return to 'pure' religious practices, such as Wahhabism and the Bhakti movement.

Challenges to Orthodoxy: Each region experienced challenges to established religious authorities and orthodoxies, leading to the emergence of new religious expressions and communities.

Differences:

Cultural Syncretism: In Asia, particularly under the Mughal Empire, there was a greater emphasis on syncretism and blending of religious traditions compared to Europe where the Reformation often resulted in more defined and rigid denominational boundaries.

Political Context: The religious changes in Europe were deeply intertwined with political power and conflict, leading to wars like the Thirty Years' War, whereas in Asia and the Middle East, religious movements often developed within existing political structures without leading to widespread conflict.