Chapter 10.2 Western Imperialism, in Action

Second Phase of European Colonial Conquests (1750-1900)

A Second Wave of European Conquests (1750-1900)

Overview of Colonial Expansion

The period between 1750 and 1900 represented a distinct, second phase of European colonial conquests, differing from the initial phase of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries which primarily focused on the Americas.

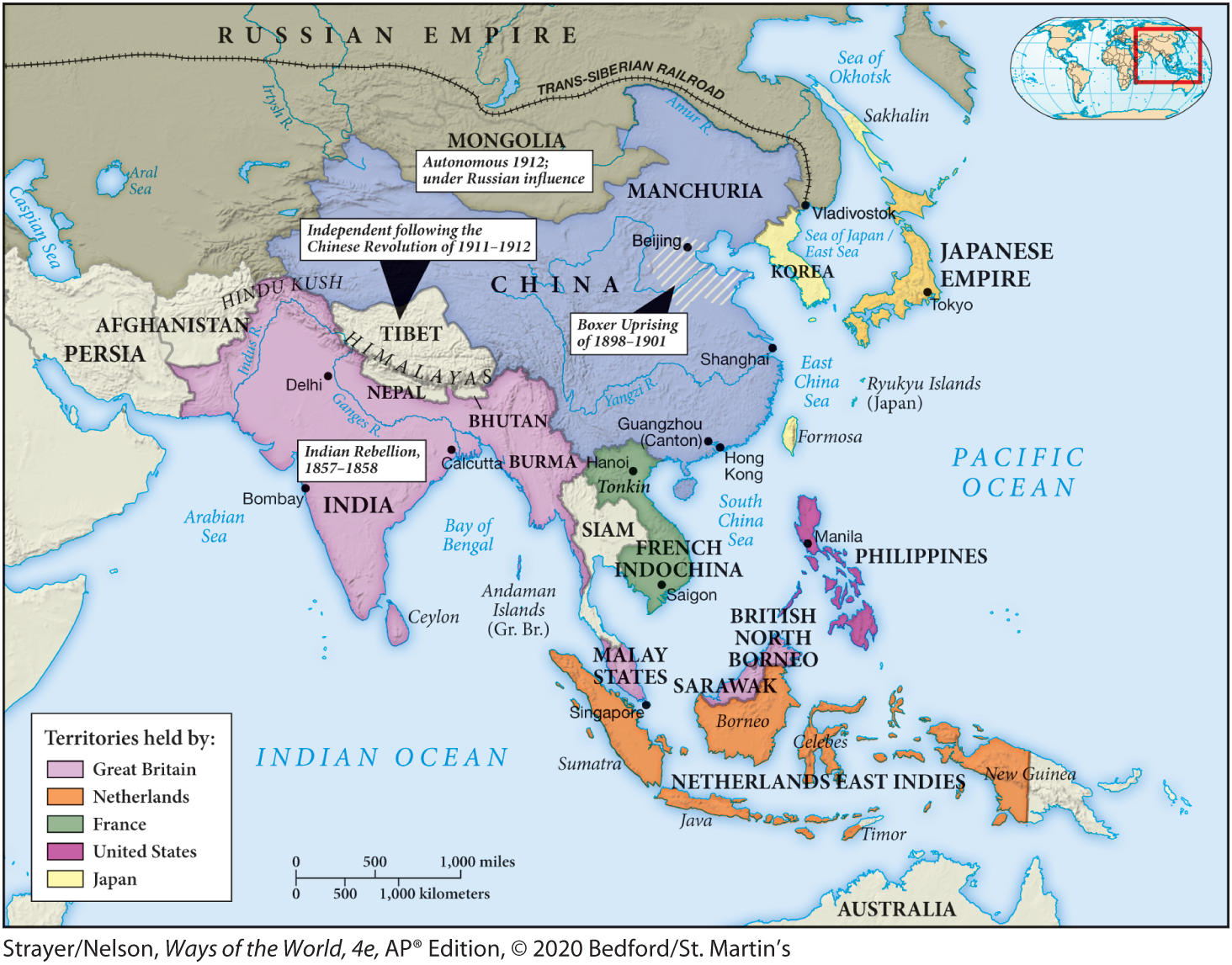

This newer phase of colonialism shifted attention towards Asia, Africa, and Oceania.

New colonial players emerged during this era, including Germany, Italy, Belgium, the United States, and Japan, marking their entry into the colonial scene, whereas the Spanish and Portuguese roles were significantly reduced compared to their dominant positions in earlier centuries.

Preference for Informal Control

European powers during this period typically preferred an informal approach to colonial control. This method involved economic penetration through trade and investment and occasional military interventions.

Informal control was favored as it was more cost-effective and less likely to provoke direct confrontations or wars with other European powers or local entities.

Circumstances Leading to Direct Conquest

In cases where rival European powers posed competition, or local governments were either unable or unwilling to cooperate with European interests, the European states found it necessary to undertake direct conquest and establish outright colonial rule.

Such actions, though more expensive and risky, were deemed necessary to secure and maintain European dominance and access to local resources.

Capitalizing on Local Instabilities

Europeans often exploited periods of weakness in local societies to strengthen and extend their control.

A noted example includes the impact of global droughts and climatic instability, particularly in the second half of the nineteenth century, which resulted in failures of monsoon rains across Asia and parts of Africa. These environmental crises provided opportunities for European powers to initiate or escalate imperial expansions.

In Africa, specific instances like the drought in southern Africa in 1877 coincided with the British efforts to suppress Zulu independence. Similarly, famine conditions in Ethiopia during the late 1880s coincided with Italian military campaigns to conquer regions in the Horn of Africa.

Military Advantages and Conquest

The European conquests were significantly aided by technological advancements in military hardware. Europeans possessed overwhelming advantages in firepower with the introduction of repeating rifles and machine guns.

Despite these advantages, establishing new empires was often a challenging process that involved prolonged and intense military campaigns. Europeans faced stiff resistance from local forces, who were generally less well-armed and often lacked any firearms.

Ultimately, European powers prevailed almost universally, establishing control over vast regions and diverse populations.

Societal Impact and Loss of Sovereignty

The establishment of European empires led to widespread loss of political sovereignty and autonomy for various indigenous and local groups across the targeted regions.

Affected groups included hunter-gatherer bands in Australia, agricultural village societies in Pacific islands and parts of Africa, pastoralists in the Sahara and Central Asia, and residents of both small states and large, complex civilizations in India and Southeast Asia.

For some groups, such as Hindus in India who were previously governed by the Muslim Mughal Empire, the shift represented a change from one set of foreign rulers to another. However, now all these diverse groups were uniformly subjected to European colonial governance.

Pathways to Colonialism

The transition to colonial status occurred through various mechanisms depending on the region:

India: The British East India Company, not the British government directly, led the colonial takeover. This process capitalized on the fragmentation of the Mughal Empire and the lack of a unified cultural or political resistance, evolving through complex interactions involving military operations and political alliances over a century (1750–1850).

Indonesia: Dutch control emerged from a landscape of numerous small and rival states. The Dutch extended their control gradually, with some areas resisting until the early twentieth century.

Late 19th Century Colonial Conquests in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific

Context and Timing of Conquests

Colonial conquests in Africa, mainland Southeast Asia, and the Pacific islands occurred later than in India or Indonesia, primarily in the second half of the nineteenth century.

This period was marked by more abrupt and deliberate conquests, with the European powers implementing well-planned and forceful strategies to secure territories.

The Scramble for Africa

The "scramble for Africa" involved intense competition among European nations, resulting in the rapid partition of the African continent among about half a dozen powers from 1875 to 1900.

European leaders were notably surprised by both the intensity of their own rivalries and the swift acquisition of vast African territories, regions about which they had minimal prior knowledge.

Negotiation and Military Campaigns

The process of partitioning Africa included extensive negotiations among European Great Powers, focusing on peaceful discussions about territorial divisions.

Alongside diplomatic efforts, there were significant military campaigns to establish and enforce control on the ground. These military efforts often lasted for decades and involved considerable violence.

Challenges in Conquest

The conquest of the West African empire led by Samori Toure by the French spanned sixteen years (1882–1898), highlighting the prolonged nature of colonial military engagements.

Europeans faced particular challenges in subduing decentralized societies without formal state structures, where there was no central authority to negotiate with or defeat decisively. In these areas, Europeans had to engage in village-by-village conquest, facing persistent and extended resistance.

Late 19th Century Colonial Conquests in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific

Context and Timing of Conquests

Colonial conquests in Africa, mainland Southeast Asia, and the Pacific islands occurred later than in India or Indonesia, primarily in the second half of the nineteenth century.

This period was marked by more abrupt and deliberate conquests, with the European powers implementing well-planned and forceful strategies to secure territories.

The Scramble for Africa

The "scramble for Africa" involved intense competition among European nations, resulting in the rapid partition of the African continent among about half a dozen powers from 1875 to 1900.

European leaders were notably surprised by both the intensity of their own rivalries and the swift acquisition of vast African territories, regions about which they had minimal prior knowledge.

Negotiation and Military Campaigns

The process of partitioning Africa included extensive negotiations among European Great Powers, focusing on peaceful discussions about territorial divisions.

Alongside diplomatic efforts, there were significant military campaigns to establish and enforce control on the ground. These military efforts often lasted for decades and involved considerable violence.

Challenges in Conquest

The conquest of the West African empire led by Samori Toure by the French spanned sixteen years (1882–1898), highlighting the prolonged nature of colonial military engagements.

Europeans faced particular challenges in subduing decentralized societies without formal state structures, where there was no central authority to negotiate with or defeat decisively. In these areas, Europeans had to engage in village-by-village conquest, facing persistent and extended resistance.

Specific Incidents of Resistance

In central Nigeria, British officials noted the destruction required to subdue local villages, with one official in 1925 expressing regret over the destructive process but acknowledging the lack of alternatives.

The British experienced significant military defeats in South Africa, notably at the Battle of Isandlwana in 1879 where they were defeated by a Zulu army.

The Boer War (1899–1902) further exemplified intense resistance, with Boers (white descendants of Dutch settlers) fighting strenuously against British conquest for three years.

European and American Involvement in Pacific Oceania

Initial Contact and Interests (18th Century)

Europeans and Americans were drawn to Pacific Oceania during the 18th century, motivated by exploration, scientific curiosity, missionary work, and economic interests in natural resources such as sperm whale oil, coconut oil, guano, mineral nitrates, phosphates, and sandalwood.

Competitive Annexations (Late 19th Century)

By the second half of the 19th century, initial exploratory and economic engagements evolved into competitive annexations by European powers and the United States.

Nations involved in claiming territories included Britain, France, the Netherlands, Germany, the United States, and newly participating Australia.

Chile also joined the imperial endeavors, targeting guano and nitrate resources and acquiring several coastal islands, including Rapa Nui (Easter Island), the easternmost island of Polynesia.

Settler Colonies in Australia and New Zealand

Nature of Colonization

The British takeover of Australia and New Zealand during the 19th century mirrored earlier North American colonization patterns rather than contemporary Asian or African conquests.

These regions experienced large-scale European settlement and faced devastating impacts from introduced diseases, which significantly reduced indigenous populations.

Demographic Impact

By 1900, diseases had reduced native populations in Australia and New Zealand by 75 percent or more.

In the early 21st century, Aboriginal Australians made up about 2.4% of Australia's population, while the Maori constituted approximately 15% of New Zealand's population.

Comparison with Other Isolated Regions

Similar to Australia and New Zealand, other isolated regions like Polynesia, Amazonia, and Siberia suffered heavily from diseases due to lack of immunity to European pathogens.

For example, the population of Hawaii plummeted from approximately 142,000 in 1823 to just 39,000 by 1896.

Other Imperial Conquests

United States Westward Expansion

The westward expansion of the United States had severe consequences for Native American populations, resembling other forms of imperial conquest.

The U.S. pursued policies aimed at removing or sometimes nearly exterminating Native American communities to make way for white settlement.

Native Americans were confined to reservations and their children were often sent to boarding schools aimed at eradicating tribal cultures under the assimilationist slogan "Kill the Indian and Save the Man."

Expansions of Imperialism in Asia and Africa

Asian Imperialism by Japan and Russia

Japan: Engaged in imperial actions similar to European nations by taking over Taiwan and Korea, marking its entry into the imperialist activities of the period.

Russia: Continued its expansion into Central Asia, bringing additional territories under European influence and control as part of its broader imperial ambitions.

U.S. Expansion and Liberian Irony

Philippines: Acquired new colonial rulers from the United States following the Spanish-American War in 1898, illustrating the U.S.'s growing imperial reach beyond its continental borders.

Liberia: Established by around 13,000 freed U.S. slaves who migrated to West Africa seeking freedom unavailable in the United States. Ironically, they set up a colonizing elite in a new land, mirroring the colonial dynamics they escaped.

Resistance and Avoidance of Colonization

Ethiopia and Siam (Thailand): Successfully avoided colonization by leveraging military and diplomatic skills, making strategic concessions, and exploiting rivalries among European imperialists.

Ethiopia: Notably expanded its own empire and secured a significant victory against Italy at the Battle of Adowa in 1896, affirming its sovereignty and resistance capability.

Siam (Thailand): Managed to maintain its independence through adept diplomacy and selective modernization, which helped maintain a balance among competing colonial powers.

Diverse Responses to Colonial Pressure

Many societies targeted by Western imperial powers exhibited a range of responses based on their local circumstances and the nature of European demands.

Internal Power Struggles: Some societies attempted to use European involvement to their advantage in internal conflicts or rivalries with neighbors.

Playing Off Imperial Powers: As pressures intensified, some leaders tried to manipulate rivalries among European powers to their own benefit.

Military Resistance: Others chose military action, facing significant challenges against superior European military technology and forces.

Negotiation for Autonomy: Some, like the rulers of the East African kingdom of Buganda, saw opportunities in European presence and negotiated terms that expanded their power and influence while aligning with British interests

AP Questions:

In what ways was colonial rule established differently in various parts of Africa and Asia?

Direct vs. Indirect Rule: In the British territories in Africa, indirect rule was often employed, using existing local hierarchies to administer colonial governance, such as in Nigeria.

In contrast, regions like French West Africa experienced more direct rule with French administrators and a centralized system.

Settler vs. Exploitation Colonies: In Asia, regions like India saw the establishment of exploitation colonies where the main goal was economic extraction with limited European settlement.

In parts of Africa like Kenya and South Africa, settler colonies for Europeans were established, significantly impacting the social structure and leading to intensive exploitation and displacement of local populations (read up on the anti-apartheid movement from Chapter 13)

Negotiated Control: In some Asian regions like Siam (Thailand) and Ethiopia in Africa, colonial control was mitigated through negotiations that led to partial sovereignty and concessions rather than full colonization.

These areas managed to retain more of their traditional governance structures compared to fully colonized regions.

What are examples of Africans' and Asians' acceptance and rejection of European imperialism?

Acceptance:

Cooperation for Benefits: Some leaders, like those in the kingdom of Buganda in East Africa, saw opportunities in European presence and negotiated arrangements that expanded their power and personal benefits, thus accepting European influence to some extent.

Adoption of European Practices: In regions like India, some elites adopted European education and legal practices, integrating them into local traditions to modernize and solidify their standing within the colonial framework.

Rejection:

Armed Resistance: Fierce resistance was seen in the Zulu wars against British forces in South Africa and the Battle of Adowa where Ethiopians successfully repelled Italian forces.

Cultural Resistance: In India, movements like the Swadeshi movement advocated for the boycott of British goods and the revival of local crafts and industries, rejecting economic and cultural imperialism.

What caused the scramble for Africa?

Economic Interests: The industrial revolution in Europe created a massive demand for raw materials and markets, which Africa could supply. Commodities such as rubber, ivory, and precious metals were highly sought after.

Strategic Rivalries: Intense rivalries among European powers, especially between Britain, France, and Germany, drove the scramble as each sought to maximize their global influence and power by acquiring more territories.

Technological Advancements: Improvements in navigation, weaponry, and medicine (such as the quinine treatment for malaria) made African exploration and conquest feasible and less hazardous than before.

Nationalism: The possession of overseas colonies became a symbol of national prestige and power, compelling nations to acquire more colonies to assert their status on the international stage.

Ideologies: European social theories of the time, like Social Darwinism, promoted the idea of the "civilizing mission" to justify imperial domination, suggesting it was Europe’s duty to civilize "lesser" races and cultures.

How was the colonization of Australia in the nineteenth century similar to the colonization of North America in the seventeenth century?

Settlement Patterns: Both Australia and North America saw significant European settlement that involved the displacement and decimation of indigenous populations. Settlers in both regions were often convicts, religious dissenters, or people seeking economic opportunities.

Impact on Indigenous Populations: In both contexts, the arrival of Europeans brought diseases to which the indigenous populations had no immunity, leading to catastrophic declines in their numbers. For instance, diseases like smallpox drastically reduced the Aboriginal population in Australia, similar to the impact on Native American communities.

Land Use and Economic Activities: The economic activities in both Australia and North America largely focused on exploiting natural resources. In North America, this included fur trading and tobacco farming, while in Australia, it centered on mining (gold and other minerals) and sheep farming.

Cultural and Legal Impositions: European settlers imposed their own cultural values, legal systems, and languages, marginalizing and often eradicating indigenous cultures and social structures in both regions.

Compare motivations and outcomes of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century imperialism.

Motivations

Economic Gain: The industrial revolution heightened the demand for raw materials and new markets, driving imperialism in both the 19th and early 20th centuries. Colonies provided the necessary resources and markets to fuel industrial economies back home.

Strategic and Political: Nations sought to expand their geopolitical influence through imperialism. Possessing colonies enhanced a nation's status and power on the global stage, often contributing to a balance of power dynamics among European states.

Cultural/Social Ideologies: Motivations were also underpinned by cultural and social ideologies such as the "White Man's Burden" and Social Darwinism, which argued that Europeans had a duty to civilize "lesser" races and spread Western values and Christianity.

Outcomes

Economic Exploitation and Infrastructure Development: Colonies were often exploited for their resources. However, colonial rule also led to the development of infrastructure like railways and roads to facilitate the extraction and transport of these resources.

Social and Cultural Disruption: Indigenous societies were profoundly disrupted. Traditional structures were dismantled, local cultures suppressed, and populations converted to Christianity, leading to long-term social changes.

Political Reconfiguration: The political landscapes of colonized regions were permanently altered. New borders were drawn without regard to ethnic or cultural divisions, setting the stage for future conflicts. Additionally, colonial administrations laid the groundwork for modern state bureaucracies.

Anti-Colonial Movements and Independence: The 20th century saw the rise of nationalist movements in colonized regions, leading to struggles for independence. These movements were often influenced by the ideas of self-determination promoted during and after World War I.