Chapter 3.2 The Sea Roads

The Sea Roads

The Sea Roads

Indian Ocean Trade Routes: ‘The Sea Roads’

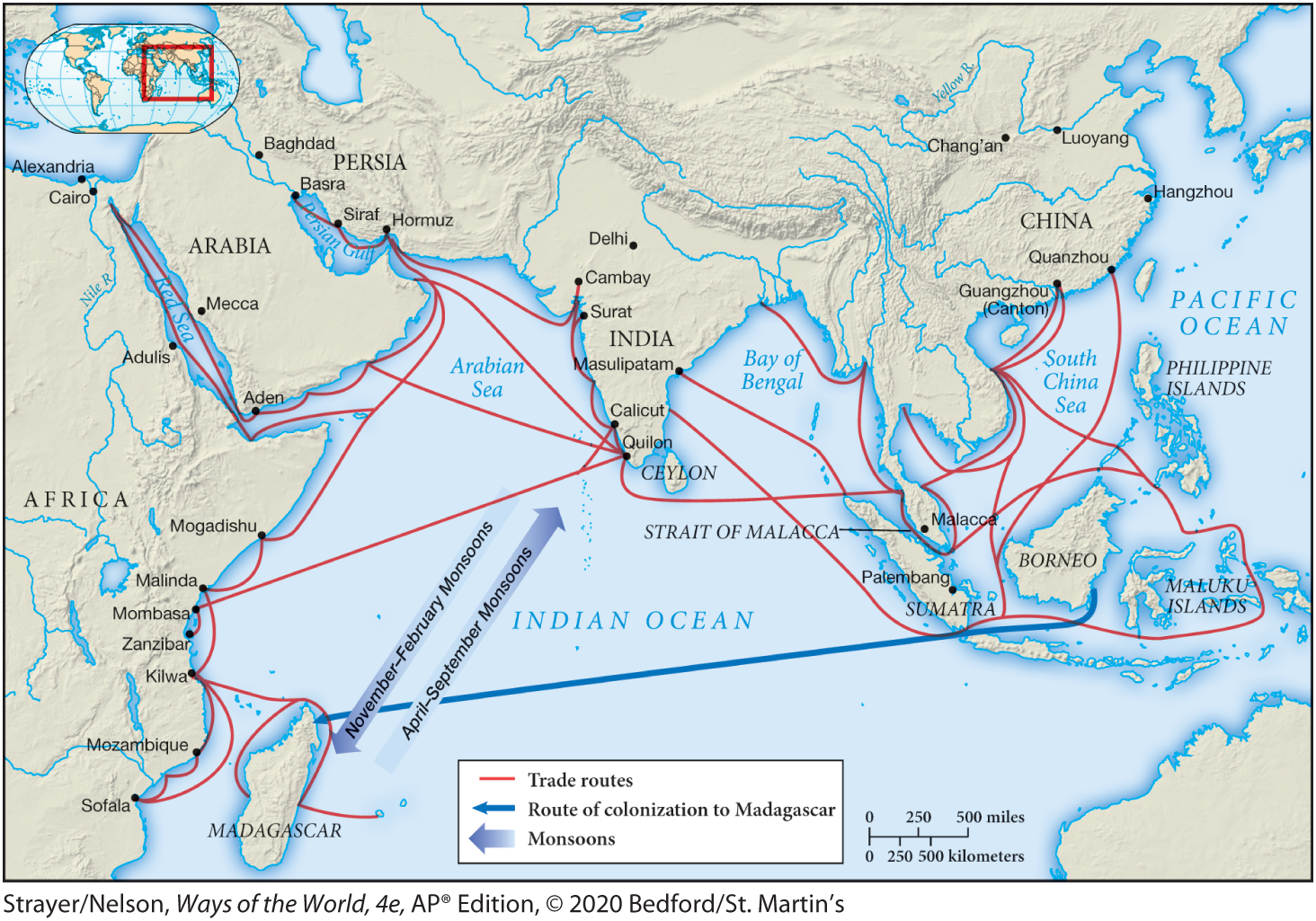

Scope and Importance: The Indian Ocean basin served as the world's largest sea-based network of communication and exchange until the emergence of global oceanic trade after 1500. It connected societies from southern China to eastern Africa, facilitating the exchange of goods and ideas across vast distances.

Factors Driving Indian Ocean Commerce:

Desire for Exotic Goods: Various goods such as porcelain from China, spices from Southeast Asia, cotton goods and pepper from India, ivory and gold from East Africa, and incense from southern Arabia drove Indian Ocean commerce as societies sought products not available locally.

Lower Transportation Costs: Sea-based trade routes offered lower transportation costs compared to overland routes like the Silk Roads, as ships could carry larger and heavier cargoes. This made the Sea Roads more conducive to the transport of bulk goods and mass-market products like textiles, pepper, timber, rice, sugar, and wheat.

Technological Developments and Facilitators of Indian Ocean Commerce:

Monsoon Winds: The alternation of monsoon winds, blowing predictably northeast during summer and southwest during winter, was crucial for Indian Ocean navigation, enabling sailors to plan their voyages effectively.

Shipbuilding and Navigation Technology: Advancements in shipbuilding techniques and navigation technology, including improvements in sails, the development of new ship types like Chinese junks and Indian or Arab dhows, and the use of tools like the astrolabe and compass, facilitated safe and efficient oceanic travel.

Chinese Economic Growth: Song China's economic expansion from the 11th century onwards played a significant role in stimulating Indian Ocean commerce. Chinese products flooded the Indian Ocean trade networks, while the thriving Chinese economy attracted goods from regions like India and Southeast Asia.

Role of Diasporic Communities:

Permanent Settlements: Foreign traders established permanent settlements along Indian Ocean trade routes, where they learned local languages, cultures, and trading practices while maintaining connections with their home societies.

Diasporic Communities: These foreign merchant communities, known as diasporic communities, played a crucial role in facilitating commercial exchange between different peoples and introducing new religious traditions to host societies. They acted as intermediaries in cross-cultural interactions and trade transactions.

Commerce, State Building, Religion in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia's Role in Indian Ocean Commerce:

Geographical Significance: Located between the major civilizations of China and India, Southeast Asia played a crucial role in Indian Ocean commerce due to its strategic position. It served as a bridge connecting the maritime trade networks of the Indian Ocean basin.

Emergence of Cities and States in Southeast Asia:

Timeline: Between 600 and 1500, a series of cities and states or kingdoms emerged on both the islands and mainland of Southeast Asia, all of which were connected to the growing commercial network of the Indian Ocean.

Connection to Indian Ocean Trade: These cities and states engaged in trade and economic activities linked to the Indian Ocean, contributing to the region's prosperity and cultural exchange.

Introduction of Religious Traditions:

Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam: Traders and sailors from the Indian Ocean introduced three major religious traditions to Southeast Asia — Buddhism, Hinduism, and later, Islam. These religions spread alongside commercial networks, influencing local cultures and societies.

Cultural and Religious Exchange: Similar to the Silk Roads, the Sea Roads facilitated not only economic but also cultural exchange, as religious ideas and practices were disseminated across Southeast Asia.

A Case Study: The Srivijaya Kingdom:

Emergence: Srivijaya, a Malay kingdom, emerged as a dominant power in Southeast Asia from 670 to 1025. It controlled the critical choke point of Indian Ocean trade through the Straits of Malacca.

Factors for Success: Srivijaya's success was attributed to factors such as its abundant gold supply, access to highly sought-after spices, and revenue from taxes imposed on passing ships.

Cultural Influence: Srivijayan monarchs adopted Indian political ideas and Buddhist religious concepts, incorporating them into their governance and society. The capital city of Palembang became a cosmopolitan hub influenced by Indian culture and language.

Religious Center: Srivijaya became a major center of Buddhist observance and teaching, attracting monks and students from across the Buddhist world.

Spread of Indian Culture in Southeast Asia:

Sailendra Kingdom: The Sailendra kingdom in central Java, closely allied with Srivijaya, undertook a massive building program between the eighth and tenth centuries, featuring Hindu temples and Buddhist monuments.

Borobudur: The most famous monument from this period, Borobudur, is an enormous mountain-shaped structure with elaborate carvings illustrating Buddhist teachings. Despite its Indian influence, Borobudur is a distinctly Javanese creation, reflecting local culture and beliefs. It represents the process of Buddhism becoming culturally grounded in Southeast Asia.

Indian Ocean Commerce and Hinduism:

By 1000 CE, Hinduism found a place in Southeast Asia, facilitated by Sea Roads commerce.

The Champa kingdom in southern Vietnam embraced Shiva worship and revered cows and phallic imagery.

The Khmer kingdom of Angkor built Angkor Wat, showcasing Hindu cosmology with Mount Meru as its center.

Commercially, the Khmer kingdom exported forest products and welcomed Chinese merchants as part of its diasporic community.

Islam's Spread through Sea Roads:

Introduction of Islam to Southeast Asia:

By 1400, Islam spread through the Indian Ocean, drawing Southeast Asian states into its fold.

Southeast Asian rulers embraced Islam to attract Muslim traders from Persia, Arabia, and India.

Islam blended with existing Hindu, Buddhist, and shamanistic practices in the region.

Rise of Malacca as a Commercial Hub:

Establishment of Malacca:

Founded in the early 14th century by a Sumatran prince, Malacca grew rapidly into a major port city.

It served as the capital of a Malay Muslim sultanate until Portuguese conquest in 1511.

Its strategic location on the Straits of Malacca made it pivotal in Indian Ocean trade.

Cosmopolitan Nature of Malacca:

By the late 15th century, Malacca had a diverse population of around 100,000, making it the largest city in Southeast Asia.

It attracted around 15,000 foreign merchants from various regions, creating a multicultural society.

Foreign merchant communities in Malacca had their own neighborhoods and played roles in trade mediation and governance.

Economic Significance and Trade Relations:

Malacca served as a key hub for trade between different nations across vast distances.

Tribute missions to China and trade with Chinese merchants boosted Malacca's economic and political standing.

Pepper trade, in particular, was lucrative, with Malacca acting as a transit point for pepper from Sumatra and southern Thailand to China.

Role in Islamic Spread and Culture:

Malacca played a significant role in the spread of Islam throughout the region.

It became a center for Islamic learning, attracting students from across Southeast Asia.

Despite its rough reputation and cultural blending, Malacca fostered an international maritime culture shaped by Islam.

Impact of Islam and Maritime Culture:

Maritime Culture and Islam:

Islam's expansion fostered an international maritime culture by the 12th century.

Conversion to Islam facilitated commercial transactions and stimulated widespread cultural blending.

Even non-Muslim rulers adopted Muslim names for commercial benefits, contributing to the maritime Silk Road's Islamic character.

AP Causation: How could technological developments, such as this dhow ship, help transform the culture of the Indian Ocean region?

Facilitating Trade and Communication: Dhow ships enabled more efficient trade and communication between different regions, fostering cultural exchange and interconnectedness. This would lead to more travel and trade between these areas and eventually cultural diffusion which would enrich and change the cultures in the Indian Ocean region.

Commerce, State Building, and Religion in East Africa

Emergence of Swahili Civilization:

The Swahili civilization began to develop in the eighth century C.E. along the East African coast, spanning from present-day Somalia to Mozambique.

It evolved into a network of commercial city-states fueled by long-distance trade across the Indian Ocean.

Stimulus for Growth:

The growth of Swahili cities was propelled by the extensive commercial activity in the western Indian Ocean, particularly following the rise of Islam.

Local communities seized opportunities for wealth and power by trading East African products like gold, ivory, quartz, and slaves for goods from distant civilizations.

Development of Urban Centers:

By 1200, Swahili civilization flourished along the coast with cities boasting populations of 15,000 to 18,000 people, including Lamu, Mombasa, Kilwa, and Sofala.

These cities were politically independent, each governed by its own king, and engaged in competitive trade relations with neighboring city-states.

Economic Structure:

Swahili cities served as commercial hubs accumulating goods from the interior regions and exchanging them for products from distant civilizations, such as Chinese porcelain, silk, Persian rugs, and Indian cottons.

Long-distance trade generated class-stratified urban societies with a clear distinction between a wealthy mercantile elite and commoners.

Maritime Trade:

While transoceanic journeys primarily occurred in Arab vessels, Swahili craft navigated coastal waterways, concentrating goods for shipment abroad.

This maritime trade network facilitated the exchange of commodities and contributed to the prosperity and growth of Swahili city-states.

Comparison to Other Trading Empires:

Unlike empires like Srivijaya and Malacca, which controlled critical trade chokepoints, Swahili city-states operated independently without a unified imperial system.

However, they played a significant role in the Indian Ocean trade network, accumulating wealth and fostering cultural exchange with distant civilizations.

Cultural Integration in Swahili Civilization:

Swahili civilization actively participated in the larger Indian Ocean world, welcoming Arab, Indian, and Persian merchants who settled permanently as diasporic communities.

Many ruling families of Swahili cities claimed Arab or Persian origins to enhance their prestige, while simultaneously adopting cultural practices from various regions, such as dining from Chinese porcelain and dressing in Indian cottons.

Language and Artistic Influence:

The Swahili language, a Bantu language, was written in Arabic script and incorporated Arabic loanwords, reflecting the cultural exchange between East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula.

Artifacts like a bronze lion found in the Swahili city of Shanga, crafted in an Indian artistic style from melted-down Chinese copper coins, illustrate the cosmopolitan character of Swahili culture.

Islamic Influence:

Islam spread rapidly in Swahili civilization, introduced by Arab traders and widely adopted by the local population.

Mosques became prominent features of Swahili cities, connecting them to the larger Islamic world of the Indian Ocean.

Impact on the African Interior:

While Islam did not penetrate far into the African interior, the influence of Indian Ocean trade extended inland, particularly in regions rich in gold between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers.

The emergence of powerful states like Great Zimbabwe was closely tied to trade in gold and the wealth derived from cattle herding.

Spread of Agricultural Products:

Indian Ocean voyaging facilitated the spread of agricultural products like the banana from Southeast Asia to Africa.

The banana's introduction enhanced agricultural productivity, facilitated population growth, and laid the economic foundation for the rise of chiefdoms and states in various parts of the African continent, such as the kingdoms of Bunyoro and Buganda during the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries.

AP Questions:

What was the role of the Swahili civilization in the world of Indian Ocean commerce?

The Swahili Civilization emerged as a network of commercial city-states along the East African coast.

It actively participated in Indian Ocean commerce by trading goods such as gold, ivory, quartz, and slaves acquired from the interior for products from distant civilizations like Chinese porcelain, Persian rugs, and Indian cottons.

Swahili cities welcomed Arab, Indian, and Persian merchants, fostering cultural exchange and facilitating the spread of Islam in the region.

To what extent did the Silk Roads and the Sea Roads operate in a similar fashion? How did they differ?

Similarities:

Both facilitated long-distance trade and cultural exchange across vast regions.

They contributed to the integration of diverse societies and the spread of religions and technologies.

Differences:

The Silk Roads primarily connected Eurasian landmasses, while the Sea Roads linked coastal regions around the Indian Ocean basin.

Transportation on the Silk Roads relied on overland routes, mainly utilizing caravans of camels, whereas the Sea Roads utilized maritime routes, relying on ships.

Goods traded on the Silk Roads were often luxury items for elites, while the Sea Roads transported bulk goods and products for mass markets such as textiles, spices, and agricultural products.

Chinese Maritime Voyages in the Indian Ocean

Ming China’s Maritime Expeditions of the 1400s:

Initiated by Emperor Yongle of the Ming dynasty, a series of massive maritime expeditions were launched from China between 1405 and 1433.

Led by the Muslim eunuch Zheng He, these expeditions aimed to extend Chinese influence and establish diplomatic relationships with distant peoples and states across the Indian Ocean basin.

Great Chinese admiral who commanded a huge fleet of ships in a series of voyages in the Indian Ocean that began in 1405. Intended to enroll distant peoples and states in the Chinese tribute system, those voyages ended abruptly in 1433 and led to no lasting Chinese imperial presence in the region.

Visiting ports in Southeast Asia, Indonesia, India, Arabia, and East Africa, the fleets sought to enroll distant peoples and states in the Chinese tribute system, enhancing Chinese power and prestige in the region.

The Chinese did not conquer any territories, but they forced rulers of various East Asian civilizations into tribute: rituals of submission with gifts, titles, and trading opportunities.

End of the Expeditions:

Despite initial success, the expeditions abruptly ended after 1433, with the Chinese authorities halting further voyages and allowing the fleet to deteriorate.

Reasons for the termination included the death of Emperor Yongle, opposition from high-ranking officials who saw the expeditions as wasteful, and the perception of China as a self-sufficient "middle kingdom" with little need for external resources.

Consequences:

The withdrawal from the Indian Ocean by the Chinese government facilitated European entry into the region, clearing the way for Portuguese exploration and eventual colonization.

While the voyages were initially forgotten in China's historical memory, their revival in the 21st century coincided with China's reentry onto the global stage, highlighting their significance in shaping world history and maritime exploration.