Chapter 4.3 The Mongol Network

Toward a Eurasian Economy:

Promotion of International Commerce:

The Mongol Empire, although not actively engaged in trade, strategically promoted international commerce to extract wealth from more developed civilizations.

Under the rule of Great Khan Ogodei, merchants were incentivized through generous payments and financial support for caravans. Standardized weights and measures were introduced, and tax breaks were granted to facilitate trade.

Facilitation of Long-Distance Trade:

Under the Pax Mongolica, the Mongol Empire provided a relatively secure environment for merchants traveling along the Silk Roads, effectively bridging the gap between Europe and China.

European merchants, particularly from Italian cities, embarked on journeys to China that were facilitated by that peace within the empire. Guidebooks circulated with valuable advice for these traders, highlighting the importance of Mongol-sponsored trade routes.

Discovery of Prosperous Markets:

European merchants, including figures like Marco Polo, returned with accounts of the prosperous commercial opportunities in China. Their accounts revealed previously unknown trading networks and economic potential to the Europeans.

This exchange of information significantly expanded Europeans' understanding of the interconnectedness of Eurasian markets and the vast opportunities available.

Engagement of the Islamic World:

Traders and travelers from the Islamic world actively participated in commerce along both the Silk Roads and the Sea Roads of the Indian Ocean, interacting with Mongol-controlled territories.

Figures such as Ibn Battuta journeyed to China, following established trade routes of Arab merchants. Despite cultural discomfort, Muslim communities were established in various Chinese provinces, reflecting the cosmopolitan nature of Mongol-linked commerce.

Formation of a Commercial Network:

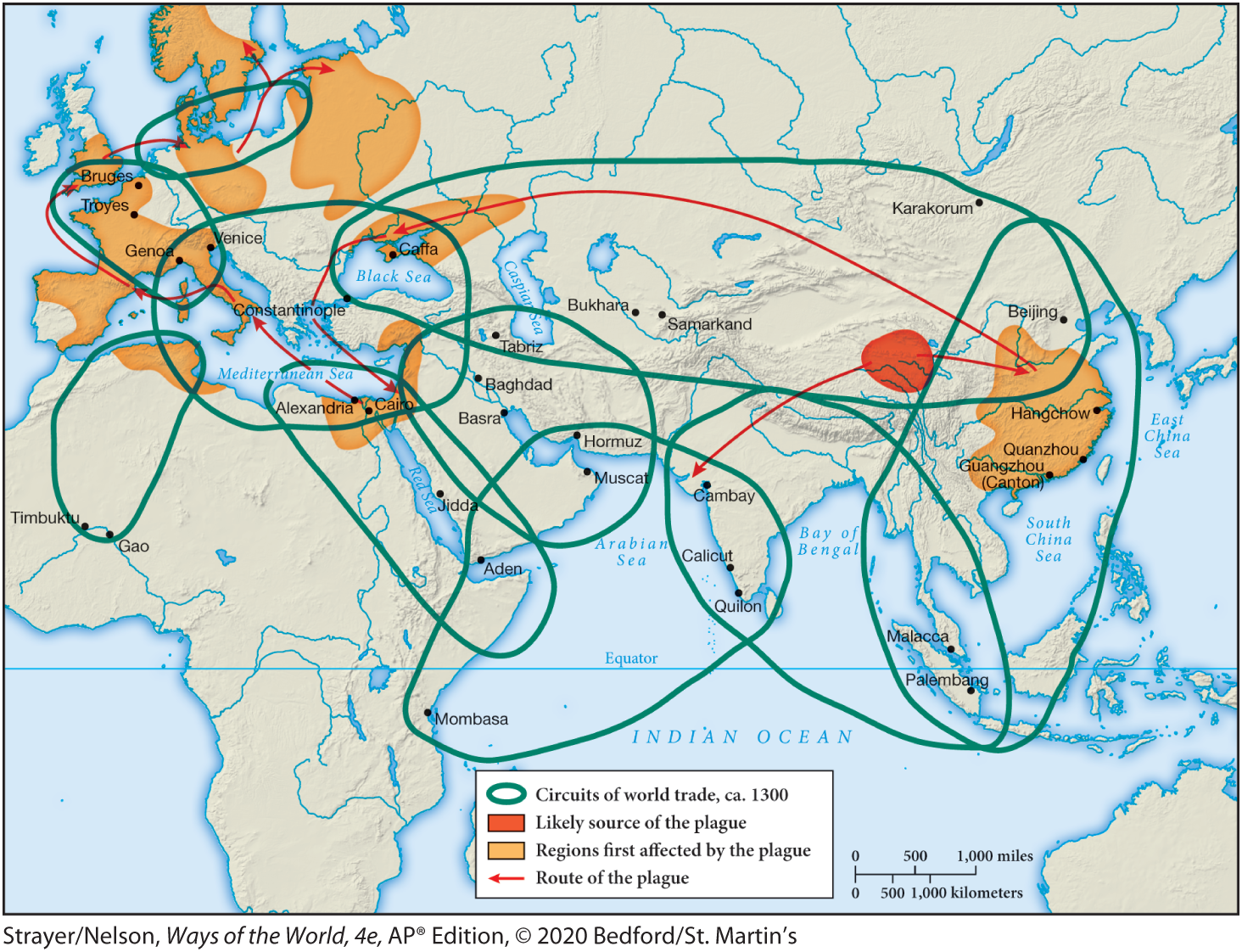

The Mongol trading circuit served as a central element in a larger commercial network that interconnected much of the Afro-Eurasian world in the thirteenth century.

Mongol-ruled China acted as a pivotal point, linking overland routes through the Mongol Empire with maritime routes through the South China Sea and Indian Ocean, fostering economic integration and exchange across diverse regions.

Diplomacy on a Eurasian Scale

Expansion into Europe:

Mongol armies, following their invasion of Russia, devastated Polish, German, and Hungarian forces in 1241–1242. They appeared poised to march further into Central and Western Europe but were forced to retreat due to the death of Great Khan Ogodei. Additionally, Western Europe lacked suitable pasture for Mongol herds, sparing it from direct conquest.

European Diplomatic Outreach:

Fearing a potential return of the Mongols, both the Pope and European rulers dispatched delegations to the Mongol capital, primarily led by Franciscan friars. Their objectives included understanding Mongol intentions, securing Mongol assistance in Christian crusades against Islam, and attempting to convert Mongols to Christianity.

Despite these efforts, alliances or widespread conversions did not materialize. Instead, one mission returned with a demand from the Great Khan Guyuk for European submission.

European Awareness and Information Exchange:

European missions to the Mongol Empire provided valuable information about the lands to the east, contributing to a growing European awareness of the wider world. These reports were instrumental in shaping European perceptions of the Mongols and provided historians with significant insights.

In 1287, the Ilkhanate of Persia sought an alliance with European powers to reclaim Jerusalem and counter Islamic forces. However, the conversion of Persian Mongols to Islam halted any potential anti-Muslim coalition.

Inter-Empire Diplomatic Relations:

Within the Mongol Empire, close diplomatic ties were fostered between the courts of Persia and China. Regular exchange of ambassadors, sharing of intelligence, facilitation of trade, and movement of skilled workers characterized these relations.

The establishment of diplomatic relationships between political authorities across Eurasia marked a significant departure from previous interactions, facilitating communication and cooperation on a scale previously unseen.

Cultural Exchange within the Mongol Realm

Forced Migration and Religious Diversity:

Mongol policies forcibly relocated skilled craftsmen and educated individuals across the empire, fostering cultural exchange.

Religious tolerance and support for merchants attracted missionaries and traders from various regions.

The Mongol capital at Karakorum epitomized cosmopolitanism, featuring places of worship for Buddhists, Daoists, Muslims, and Christians. Mongol rulers, including Chinggis Khan, entered into marriages with Christian women, reflecting a relatively open outlook that facilitated the blending of religious ideas.

Cross-Cultural Influences:

In Persia, artistic depictions drawing on Chinese techniques portrayed the Prophet Muhammad, incorporating elements from Buddhist and Christian traditions. This exchange extended to entertainment at the Mongol court, where actors, musicians, wrestlers, and jesters from diverse regions entertained.

Exchange of personnel between regions facilitated the transfer of skills and knowledge. Persian and Arab doctors and administrators were dispatched to China, while Chinese physicians and engineers found employment in the Islamic world.

Technological and Agricultural Exchange:

Mongol authorities actively encouraged the exchange of ideas and techniques, leading to the westward flow of Chinese technology and artistic conventions. Chinese inventions such as printing, gunpowder weapons, compass navigation, and medical techniques were introduced to the Middle East and Europe.

Sensibilities shaped the reception of foreign ideas; for instance, acupuncture faced resistance in the Middle East due to cultural norms, but Chinese diagnostic techniques gained popularity.

Exchange of plants and crops occurred within the Mongol realm, with Middle Eastern produce like lemons and carrots finding favor in China, and Persian rulers seeking unique seeds from India and China.

Impact on Europe:

Europeans, relatively less technologically advanced and isolated from Asian exchanges, benefited greatly from these interactions. They gained access to new technology, crops, and knowledge, contributing to their development.

Europe's avoidance of direct Mongol conquest allowed it to capitalize on these exchanges without suffering the devastating consequences experienced by other regions.

Some historians argue that Europe's advantageous position in these exchanges laid the groundwork for its subsequent rise to global prominence.

The Black Death: An Afro-Eurasian Pandemic

Origins and Spread:

Originating in China, the Black Death, caused by the bacteria Yersinia pestis, spread across the Mongol trade routes in the early fourteenth century. It reached the Middle East and Western Europe by 1347 and East Africa by 1409.

Carried by rodents and transmitted by fleas to humans, the plague caused severe symptoms such as swelling of lymph nodes, headaches, high fever, and internal bleeding, leading to high mortality rates.

Devastating Consequences:

The densely populated civilizations of China, the Islamic world, and Europe, as well as the steppe lands, experienced catastrophic loss of life. Chroniclers reported death rates ranging from 50 to 90 percent of the affected population.

In Europe, about half of the population perished during the initial outbreak of 1348–1350. Cities like Cairo were deserted, and the Middle East lost perhaps one-third of its population by the early fifteenth century.

The plague's intense first wave was followed by periodic outbreaks over the next centuries, although regions like India and sub-Saharan Africa were less affected.

Responses at the ground level:

Individuals turned to religion to find meaning, comfort, and protection in the face of the catastrophe. Penitents sought mercy or atonement through prayer and religious rituals, and religious communities sometimes came together in joint ceremonies.

Some individuals, however, did not turn to religion and instead engaged in reckless behavior, indulging in pleasures and revelry despite the crisis.

Long-Term Social Changes in Europe

Labor Shortages and Conflict:

The Black Death caused labor shortages, leading to conflicts between workers demanding higher wages or better conditions and the rich who resisted these demands.

Peasant revolts in the fourteenth century reflected tensions arising from labor shortages and undermined the institution of serfdom.

Impact on Technological Innovation and Gender Roles:

Labor scarcity may have spurred greater interest in technological innovation and created more employment opportunities for women, contributing to changes in traditional gender roles.

Consequences for the Mongol Empire and Global Trade

Disruption of the Mongol Network:

The Black Death contributed to the decline of the Mongol Empire in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, as population decline, city decay, and reduced trade volume affected the entire Mongol world.

By around 1350, the Mongol Empire was in disarray, and within a century, they lost control of Chinese, Persian, and Russian civilizations.

Shift to Maritime Exploration:

Disruption of the land routes to the East incentivized Europeans to explore sea routes to Asia, seeking to avoid Muslim intermediaries.

European naval technology provided them with military advantages at sea, akin to the Mongols' prowess in land battles.

A Comparison: European Expansion:

European expansion into Asian and Atlantic waters in the sixteenth century mirrored the Mongols' role in organizing world trade and fostering communication and exchange.

Like the Mongols, Europeans plundered wealthier civilizations encountered during their expansion, leading to devastating consequences such as disease and population decline.

European Imperialism Compared to Mongol Conquests:

European imperial presence lasted longer and operated on a larger scale compared to Mongol conquests.

However, both European expansion and Mongol conquests brought cultural, linguistic, and technological influences to the societies they encountered.

Early European expansion shared some similarities with Mongol conquests, earning Europeans the moniker "the Mongols of the seas" for their role in global trade and imperialism.