Chapter 3.3 The Sand Roads, Islam, & Americas

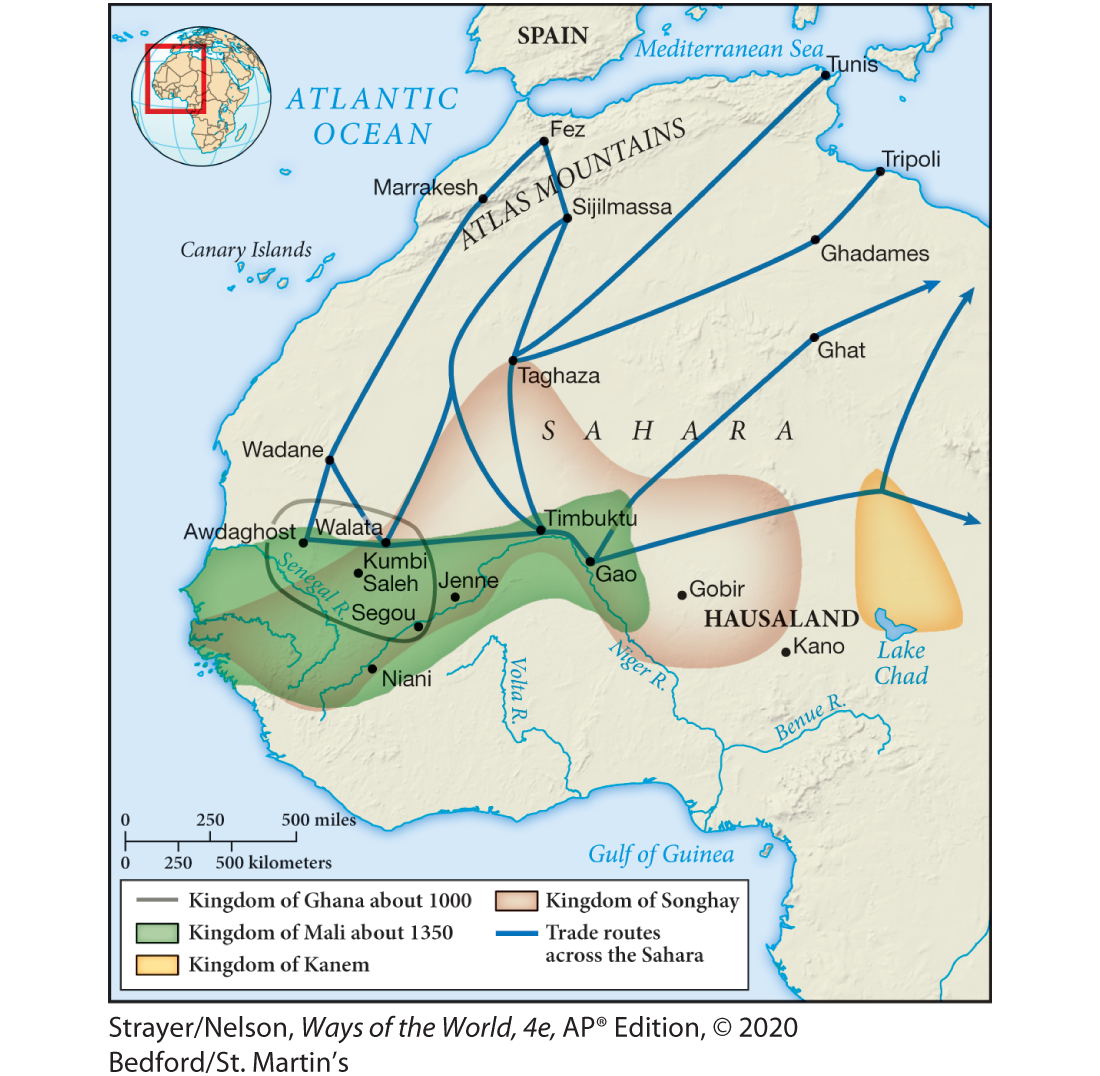

The Sand Roads: the trans-Saharan route that linked interior West Africa to the Mediterranean and North Africa. Islam strengthened the trade connections and state building for the kingdoms shown in this map by giving them a common religion that could connect them to the Islam Empire and other Islamic territories (enriched their trade and resources).

The Sand Roads, as a Trade Network:

Role and Scope: Linked North Africa and the Mediterranean world with the interior regions of West Africa as a dominant trade network.

Impact: Played a transformative role in shaping and enriching West African civilization prior to the emergence of the European slave trade, contributing to economic prosperity and cultural exchange.

Environmental Variation and Trade Incentives:

North African Coast: Produced a range of manufactured goods such as cloth, glassware, weapons, and books, reflecting the region's historical ties to Roman and Arab empires.

Saharan Region: Abundant in natural resources like copper and salt, while oases yielded sweet and nutritious dates, providing essential commodities for trade.

Sub-Saharan Africa: Characterized by varied ecological zones, including savanna grasslands and forested areas, fostering the cultivation of crops like millet, sorghum, yams, and kola nuts. This diversity created economic incentives for interregional trade.

Introduction of the Arabian Camel:

In the early centuries of the Common Era, the introduction of the Arabian camel facilitated long-distance trade across the Sahara Desert, revolutionizing trans-Saharan commerce.

Could go for ten days without water, making long-distance trade across the Sahara possible. The camel's ability to endure long journeys across the desert facilitated the establishment of regular trade routes, enabling the transportation of goods over vast distances.

Role in Trade Expansion: Camel-owning inhabitants of desert oases pioneered regular trans-Saharan trade routes, allowing for the transportation of goods and commodities across vast distances.

Islamic Influence: With the spread of Islam, North African Arabs organized and facilitated caravans for Arabian-camel-bound-travelers across the Sahara. These caravans not only facilitated trade but also the dissemination of Islamic teachings and cultural practices.

Trade Goods and Demands:

Arab Merchants' Demands: Arab traders primarily sought coveted commodities from West Africa, including gold, ivory, kola nuts, and slaves.

West African Exchange: In return for these sought-after goods, West African civilizations received a variety of items from North Africa, such as horses, cloth, dates, manufactured goods, and salt, which was particularly valuable due to its scarcity in the southern regions.

Commerce and State Building in West Africa

Geopolitical Landscape and Emergence of West African Civilization:

West African Civilization developed in response to the economic opportunities of trans-Saharan trade (especially control of gold production), it included the states of Ghana, Mali, Songhay, and Kanem, as well as numerous towns and cities.

Geographical Advantage: The West African savannah grasslands, positioned between the Sahara Desert and the forested regions, served as a strategic location for trade and cultural exchange.

Chronological Span: The civilization flourished from around 600 to 1600, encompassing territories from the Atlantic coast to Lake Chad.

Political Entities: Major empires such as Ghana, Mali, Songhay, and Kanem dominated the region, along with numerous city-states like Kano, Katsina, and Gobir.

Hausa City-States and Urban Culture:

Comparison: The Hausa city-states in northern Nigeria mirrored the Swahili city-states of East Africa, boasting vibrant urban centers and commercial hubs.

Economic Specialization: Cities like Kano excelled in textile production, particularly dyed cotton textiles, which became prized commodities in regional and trans-Saharan trade.

Economic Foundations and Taxation:

Trade Networks: Trans-Saharan trade routes facilitated the exchange of goods such as gold, ivory, kola nuts, and slaves, driving economic growth and prosperity.

Royal Patronage: West African rulers wielded economic power by monopolizing strategic resources, levying taxes on trade, and accumulating wealth. This economic control bolstered their political authority and international prestige.

Monarchical Structure and Administrative Complexity:

Monarchies: West African states operated under monarchical systems characterized by elaborate court structures and centralized authority.

Administrative Machinery: These states exhibited varying degrees of administrative sophistication, with systems for taxation, justice, and governance in place to manage their territories and resources.

Military Forces: The rulers maintained military forces to defend their territories, enforce taxation, and expand their influence through conquest or diplomacy.

Economic Prosperity and Trans-Saharan Trade:

Definition: A fairly small-scale commerce in enslaved people that flourished especially from 1100 to 1400, exporting West African slaves across the Sahara for sale in Islamic North Africa.

Wealth Accumulation: Trans-Saharan trade routes facilitated the accumulation of wealth, with rulers leveraging their control over trade to amass riches.

Taxation: Merchants engaged in trans-Saharan trade were subject to taxation, providing a significant source of revenue for the state.

Reputation for Riches: West African states gained renown for their affluence, attracting merchants, travelers, and envoys from distant lands.

Monarchical Governance and Administrative Systems:

Centralized Authority: West African states were ruled by monarchies characterized by strong centralized authority.

Mali's king (Mansa Musa) exercised absolute power over political, economic, and military affairs.

Administrative Structure: These kingdoms developed sophisticated administrative systems to govern their territories effectively.

Bureaucratic Apparatus: A bureaucracy comprising officials and administrators managed various aspects of state affairs, including taxation, justice, and diplomacy.

Royal Council: The king surrounded himself with a council of advisers and officials who assisted in decision-making and governance.

Economic Foundations and Wealth Accumulation:

Trans-Saharan Trade: West African prosperity was closely linked to control over trans-Saharan trade routes.

Gold Trade Dominance: Mali's control over lucrative gold mines facilitated wealth accumulation and attracted merchants from distant regions.

Salt Trade: West African kingdoms also profited from the salt trade, exploiting salt deposits in the Sahara to trade with neighboring regions.

Taxation and Revenue: Revenue generated from trade taxes and tribute payments bolstered the economic strength of the state.

Commercial Centers: Major cities such as Timbuktu and Gao emerged as thriving commercial centers, attracting traders from distant lands.

Taxes imposed on goods passing through trade routes provided a steady stream of income for the kingdom.

Social Stratification and Hierarchical Structures:

Distinct Social Classes: West African society was stratified into distinct social classes based on wealth, occupation, and status.

Nobility and Elites: Nobles and elites occupied the highest rungs of society, enjoying privileges and wielding influence at the royal court.

Merchants and Artisans: Wealthy merchants and skilled artisans formed a prosperous middle class, contributing to economic growth and cultural development.

Peasants and Laborers: The majority of the population consisted of peasants and laborers engaged in agriculture, mining, and other manual labor.

Slavery: Slavery was a staple of West African societies, with enslaved individuals serving in various capacities, including domestic work, agriculture, and trade.

Gender Dynamics and Cultural Norms:

Male Dominance in Governance: Men predominantly held positions of power and authority in governance, commerce, and religious institutions.

Kingship: Kingship was reserved for males, with succession typically passing through patrilineal descent.

Female Contributions and Roles: Despite patriarchal structures, women made significant contributions to society in various spheres.

Economic Activities: Women played essential roles in agriculture, trade, and craft production, contributing to household economies and community development.

Cultural Practices: Gender roles were reinforced through cultural practices, rituals, and oral traditions that emphasized male leadership and female nurturing roles.

Queen Mothers: In some societies, queen mothers wielded considerable influence in matters of succession and governance, acting as advisers to the ruling elite.

Islam in West Africa

Introduction of Islam through Trade:

Spread: Islam was introduced to West Africa primarily by Muslim traders traversing the Sahara Desert, rather than through conquest.

Its adoption in West Africa was voluntary and gradual, driven by trade interactions with North African merchants.

Urban Centers: Initially accepted in urban centers, Islam provided a cultural and religious link for African merchant communities with their Muslim trading partners.

Role of Islam in West African Society:

Religious Legitimacy: Islam provided religious legitimacy for West African monarchs and their courts, enhancing their prestige and authority.

Administrative Support: The presence of literate Muslims facilitated state administration, with many serving as officials in the royal court.

Cultural Exchange: Islam became a unifying cultural force, connecting West Africa to the wider Islamic world and fostering intellectual exchange.

Prominent Figures and Religious Practices:

Mansa Musa: The pilgrimage of Mansa Musa, the ruler of Mali, to Mecca in 1324, highlighted the significance of Islam in West African society and its integration into the global Islamic community.

Timbuktu, a Center of Learning: Timbuktu emerged as a renowned center of Islamic scholarship, boasting numerous Quranic schools and libraries holding valuable manuscripts.

Religious Architecture: Monarchs subsidized the construction of mosques, contributing to the architectural landscape of West African cities.

Cultural Adaptation and Africanization of Islam:

Urban Elites: Islam remained primarily the religion of urban elites, while rural areas retained indigenous African religious practices.

Social Customs: Islamic practices coexisted with traditional customs, with rulers balancing adherence to Islamic law with respect for local traditions.

Africanized Islam: Islam in West Africa became Africanized, incorporating local customs and sensibilities, rather than strictly adhering to Arab or Islamic norms.

Gender Relations: Despite the adoption of Islam, traditional gender norms persisted, with practices such as veiling not widely observed.

Cultural Syncretism: Islam coexisted with indigenous African religions, leading to syncretic religious practices and beliefs.

Governance: Rulers governed in accordance with a blend of Islamic law and traditional governance systems, ensuring social harmony by respecting the beliefs of their subjects.

Connections across the Islamic World

Transcontinental Islamic Trade Networks:

Geographic Scope: The Islamic world encompassed vast territories stretching from Spain and West Africa to the Middle East, India, and Southeast Asia, forming a comprehensive trading network.

Factors Facilitating Trade:

The strategic central location of the Islamic world allowed for the efficient exchange of goods.

Islamic teachings encouraged commerce, with laws regulating trade prominently featured in Sharia, providing a structured framework for cross-cultural exchange.

Urban Centers: Flourishing cities such as Baghdad, established as the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate in 756, became bustling commercial hubs. By 1200, Baghdad boasted a population of over half a million people, driven by the demand for luxury goods among the urban elite.

Prominence of Muslim Merchants:

Dominant Players: Arab and Persian merchants emerged as key figures in major trade routes spanning the Mediterranean, Silk Roads, Sahara, and Indian Ocean basin. Their influence extended even to distant regions like Canton, China, where Arab and Persian traders established commercial colonies, facilitating economic links between the Islamic heartland and Asia's burgeoning economies.

Expansion into Asia: The establishment of commercial outposts in Canton exemplified the far-reaching influence of Islamic trade networks.

Economic Infrastructure:

Financial Instruments: Islamic trade networks operated with sophisticated financial mechanisms, including banking systems, partnerships, and contractual arrangements, which facilitated long-distance economic transactions. These financial innovations contributed to the development of a prosperous and highly commercialized economy within the Islamic world.

Technological Exchange: The diffusion of technology played a crucial role in enhancing agricultural productivity and promoting industrial development across the Islamic world. Advanced irrigation techniques, originating from Persian reservoirs, were adopted widely, transforming arid landscapes into fertile agricultural regions. Additionally, the introduction of papermaking techniques, influenced by Chinese practices, revolutionized the dissemination of knowledge and facilitated administrative processes.

Cultural and Ecological Impact:

Agricultural Revolution: The circulation of agricultural products such as sugarcane, rice, and various fruits within and beyond the Islamic world contributed to an agricultural revolution. Advanced water management practices, including Persian-style irrigation systems, were adopted across regions, leading to increased food production, population growth, and urbanization.

Ecological Change: The widespread adoption of irrigation technologies facilitated the expansion of agricultural frontiers, supporting population growth and urban development. Moreover, the dissemination of advanced water management practices mitigated the impact of arid environments, enabling sustainable agricultural practices in previously inhospitable regions.

Technological Innovations: Islamic civilization fostered technological innovations in various fields, including rocketry, papermaking, and medicine. Arab scholars made significant contributions to algebra, astronomy, and medicine, drawing upon Greek, Hellenistic, and Indian sources to advance scientific knowledge. These advancements had profound implications for intellectual exchange and cultural development within the Islamic world and beyond.

Scholarship and Intellectual Exchange:

Translation Movement: Translation of texts from Greek, Indian, and other traditions fueled intellectual exchange and scientific progress within the Islamic world.

Institutions of Learning: Centers like the House of Wisdom in Baghdad facilitated collaboration among scholars from diverse backgrounds.

Scientific Contributions: Arab scholars made significant advances in algebra, astronomy, medicine, and pharmacology, with their medical scholarship entering Europe via Spain and influencing European medical practice for centuries.

Connections across the Americas

Limited Interactions in the Americas:

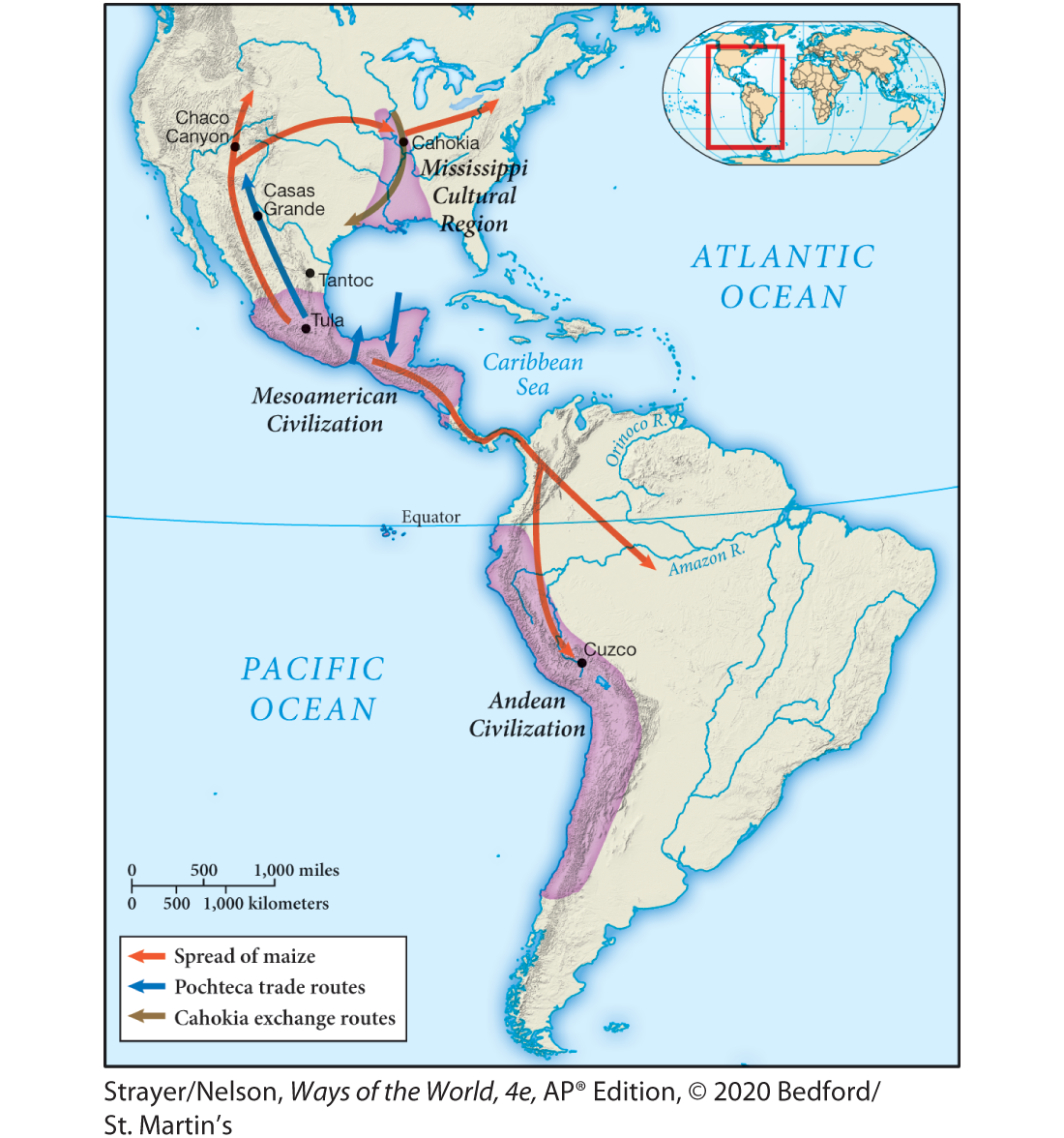

Sparse Connectivity: Direct connections among civilizations and cultures in the Americas were relatively sparse compared to Afro-Eurasia, leading to less integrated networks.

Absence of Long-Distance Trade Routes: Unlike the Silk, Sea, and Sand roads of Afro-Eurasia, there was no equivalent system of long-distance trade routes in the Americas. Instead, local and regional commerce prevailed.

Cultural Disparities: Geographic barriers and environmental differences, coupled with the absence of widespread dissemination of religious or cultural ideologies, hindered the integration of distant peoples and cultural traditions.

Obstacles to Interaction:

Transportation Challenges: The Americas lacked key transportation means such as horses, donkeys, camels, and wheeled vehicles, which limited long-distance trade and travel.

Geographic Barriers: Natural barriers like the dense rain forests of Panama and the north-south orientation of the continents impeded direct contact between South and North America, slowing the spread of agricultural products and cultural exchange.

Loosely Interactive Web:

“American Web” A term used to describe the network of trade that linked parts of the pre-Columbian Americas; although less densely woven than the Afro-Eurasian trade networks, this web nonetheless provided a means of exchange for luxury goods and ideas over large areas.

Gradual Diffusion: Crops like maize gradually spread from their Mesoamerican origins to other regions, including the southwestern United States and eastern North America, as well as to various parts of South America, indicating slow but discernible diffusion patterns.

Traces of Contact: Archeological evidence suggests some level of interaction, evidenced by the spread of cultural elements like the rubber ball game, pottery styles, and architectural conventions across different regions of the Americas.

Emergence of Commercial Nodes:

Cahokia: Located in present-day Illinois, Cahokia was a major center of trade and interaction in North America, with evidence of long-distance exchange networks.

Chaco Canyon: Situated in present-day New Mexico, Chaco Canyon served as a significant hub of commercial activity and cultural exchange, evidenced by its elaborate infrastructure and trading artifacts.

Mesoamerica: Home to civilizations like the Maya and the Aztec, Mesoamerica boasted vibrant trade networks and cultural exchange, facilitated by its strategic geographic location and complex societies.

Inca Empire: Based in the Andes, the Inca Empire emerged as a dominant force in South America, fostering extensive trade networks and interactions across its vast territory, including the exchange of goods, ideas, and technologies.

Cahokia:

Trading Network: Cahokia, located near present-day St. Louis, served as a central hub in a widespread trading network spanning North America.

Diverse Trade Goods: The network brought shells from the Atlantic coast, copper from Lake Superior, buffalo hides from the Great Plains, obsidian from the Rocky Mountains, and mica from the southern Appalachian Mountains to Cahokia.

Terraced Pyramid: Cahokia's most notable feature was a massive terraced pyramid, measuring 1,000 feet long by 700 feet wide and rising over 100 feet above the ground. It was the largest structure north of Mexico and the focal point of a community of 10,000 or more people.

Stratified Society: Evidence suggests Cahokia was a stratified society with a clear elite ruling class capable of mobilizing labor for monumental construction projects.

Chaco Canyon:

Chaco Phenomenon: Between 860 and 1130 C.E., Chaco Canyon in northwestern New Mexico experienced a period of cultural and commercial significance known as the Chaco Phenomenon.

Settlements: Five major settlements or "great houses" emerged, with Pueblo Bonito being the largest, containing over 600 rooms and numerous ceremonial pits called kivas.

Turquoise Production: Chaco became a dominant center for the production of turquoise ornaments, which were traded extensively across the region, reaching as far south as Mesoamerica.

Commercial Connections: Chacoans traded with Mesoamerican civilizations, exchanging goods such as copper bells, macaw feathers, and cacao beans.

Mesoamerica:

Maya and Teotihuacán: During the Mesoamerican civilization's peak (200–900 C.E.), the Maya cities in the Yucatán and Teotihuacán in central Mexico maintained commercial relationships with each other and the wider region.

Seaborne Commerce: The Maya engaged in seaborne commerce using large dugout canoes along both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts.

Aztec Merchants: In the Aztec Empire of the fifteenth century, professional merchants known as pochteca conducted large-scale trading expeditions within and beyond the empire's borders, often as private businessmen.

Inca Empire:

State-Run Economy: In the fifteenth century Inca Empire, economic exchange was primarily state-controlled, with no merchant class similar to the Aztec pochteca emerging.

Centralized Distribution: State storehouses stored immense quantities of goods, which were meticulously recorded on quipus by trained accountants. Caravans of human porters and llamas transported goods across the extensive road network.

Road System: The Inca road system, totaling around 20,000 miles, traversed diverse environments, facilitating transportation of goods across the empire and fostering local exchange at highland fairs and borders.