Chapter 26: Art of the Americas

Key Notes

Time Period

Chavín: 900–200 BCE (Coastal Peru)

Mayan: 300–900 CE and later (Belize Guatemala; Honduras, Yucatan)

Ancient Puebloans: 550–1400 CE (Southwestern US)

Mississippians: 800–1500 CE (Eastern US)

Aztec: 1400–1521 CE (Central Mexico)

Inka: 1438–1532 CE (Peru)

North American Indian: 18th century to present (North America)

Culture, beliefs, and physical settings

The art of the indigenous people of America is among the oldest artistic traditions in the world. It extends from about 10,000 B.C.E. through the time of the European invasions.

The art of this area can be divided into many cultural and historical groupings both in North and South America.

Ancient Mesoamerican art (from parts of Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and Belize) is characterized by architectural structures such as pyramids, a strong influence of astronomy and calendars on ritual objects, and great value placed on green objects such as jade or feathers.

Three major cultures of ancient Mesoamerica include the Olmec, the Maya, and the Mexica (also called the Aztecs).

There is a great emphasis on figural art in ancient Mesoamerica, including representations of rulers and mythical events.

Art of the central Andes (from Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador) shows a deep respect for animals and plants, as well as shamanistic religions.

The physical environment of the central Andes (the Amazon, the Andes mountains, and the coastal deserts) plays a large role in art making.

Art in central Andes was generally made by groups in workshops, rather than by individuals.

Themes in Andean art particularly address the earth-bound and the celestial.

Native North American art has diverse themes, but many of the artworks concern nature, animals, and large rituals. Respect for elders is a key unifying factor.

There is no unifying name for the native people of North America, other than terms that have been imposed by others

Cultural interactions

Mesoamerican civilizations have had a broad impact on the world as a whole.

Mesoamerican objects were valued and treasured in Europe by connoisseurs and collectors.

National museums were opened to promote an understanding of ancient American art.

Twentieth-century artists both in Latin America and elsewhere around the world have been influenced by the art of ancient America.

Current Native Americans today strongly identify with the cultural achievements of their ancestors. Art forms are maintained and revived.

There are exchanges of materials, ideas, and subject matter between Native Americans and Europeans.

Material Processes and Techniques

Mesoamericans and Native Americans use trade materials, animal-based products, and precious stones.

Works of art are generally functional.

Central Andean artists prized featherwork, textiles, and green stones, and favored works made of metal and bone.

Ceramics and wood were considered as occupying the lowest end of the artistic scale.

Pyramids began as earthworks and then grew to multilevel structures. Sites were often added to over many years.

Most architecture is made of stone, using the post-and-lintel system and faced with painted sculpture.

There are large plazas placed before the pyramids.

North American Indians produced works which included ceramics, hide paintings, basketry, weaving, adobe structures, and monumental earthworks.

Audience, functions, and patron

The modern concept of art is different than the intended purpose of objects from this period.

Objects were created to represent or contain a life force, and viewing was seen as a participatory activity.

Art was generally generated in workshops.

Rulers were the major patrons. Patrons could also include a family member, a tribal leader, or an elder.

Theories and Interpretations

There are many differences in the cultures of the Americas and therefore many approaches to studying the various art forms.

Examination of artwork from this period relies on many sources including archaeology and written accounts by colonists.

A multi disciplinary approach is used to examine the works of this period.

There are many approaches to Native North American art including archaeology, tribal history, and anthropology.

Historical Background

Humans migrated from Asia to America over a span of 30,000 years by crossing the Bering Strait.

The climate in Mexico and Central America was suitable for raising crops, leading to population growth.

Local rivalries and jealousies influenced the rise and fall of American civilizations.

American civilizations varied in terms of cultivation, technology, and lifestyle.

When European colonizers arrived, they encountered a society that was sophisticated in some ways but lacking in others, such as the absence of functional wheels and the use of refined metals mostly for jewelry.

Pre-Columbian American society is mostly understood through archaeology, including elaborate burial grounds and the ruins of ancient cities.

Successive civilizations buried or destroyed the remains of previous civilizations, so only the most durable ruins have survived.

Patronage and Artistic Life

Ancient artists were commoners but were employed by the state for their special abilities.

They were trained in an apprenticeship program and achieved fame through the creation of beautifully crafted items.

Ancient American artists used a wide variety of materials for their artwork, usually relying on what was locally available.

They were reliant on objects that were small enough to trade and carry since they did not have draught animals or wheeled carts.

Aztecs used obsidian, jade, copper, gold, turquoise, basalt, sandstone, granite, rock crystal, wood, limestone, and amethyst, among other materials.

Tropical cultures used animal skins and bird feathers to produce great works, and featherwork became a distinguished art form.

Key Terms

Ashlar masonry: carefully cut and grooved stones that support a building without the use of concrete or other kinds of masonry

Bandolier bag: a large heavily beaded pouch with a slit on top worn at the waist with a strap over the shoulders

Chacmool: a Mayan figure that is half-sitting and half-lying on his back

Corbel arch: a vault formed by layers of stone that gradually grow closer together as they rise and eventually meet

Coyolxauhqui: an Aztec moon goddess whose name means “Golden Bells”

Huitzilopochtli: an Aztec god of the sun and war; sometimes represented as an eagle or as a hummingbird

Kiva: a circular room wholly or partly underground used for religious rites

Potlatch: a ceremonial feast among northwest coast American Indians in which a host demonstrates his or her generosity by bestowing gifts

Pueblo: a communal village of flat-roofed structures of many stories that are stacked in terraces; made of stone or adobe

Relief sculpture: a sculpture that projects from a flat background

Repoussé: (French, meaning “to push back”) a type of metal relief sculpture in which the back side of a plate is hammered to form a raised relief on the front

Roof comb: a wall rising from the center ridge of a building to give the appearance of greater height

Teepee: a portable Indian home made of stretched hides placed over wooden poles

Tlaloc: ancient American god who was highly revered; associated with rain, agriculture, and war

T’oqapu: small rectangular shapes in an Inkan garment

Transformation mask: A mask worn in ceremonies by people of the Pacific Northwest, Canada, or Alaska. The chief feature of the mask is its ability to open and close, going from a bird-like exterior to a human-faced interior

Chavin Art

Chavín is a civilization in coastal Peru named after its main archaeological site.

Chavín art features figural compositions combining human and animal motifs.

Figures often unite various animal forms into one being, and are rendered with monumentality and symmetry.

Works are carved in low relief on polished surfaces in rectangular formats.

Chavín architects chose dramatic sites, sometimes on mountain tops, with buildings around a U-shaped plan facing a plaza and an expansive view.

Stepped platforms support ceremonial buildings.

The Chavín site seems to be coordinated with an adjacent river, which some say was a reference to water sources and their importance to society.

➼ Chavín de Huántar

Details

900–200 B.C.E.

Stone

Found in Northern Highlands, Peru

Function

A religious capital.

Temple, 60 meters tall, was adorned with a jaguar sculpture, a symbol of power.

Hidden entrance to the temple led to stone corridors.

Relief sculpture

Shows jaguars in shallow relief.

Located on the ruins of a stairway at Chavín.

Images

➼ Lanzón Stone

Details

900–200 B.C.E.

Granite

Found in Peru

Form

Inside the old temple of Chavín is a mazelike system of hallways.

Passageways have no natural light source; they are lit by candles and lamps.

At the center, underground, is the Lanzón (Spanish for “blade”) Stone; blade shaped; may also represent a primitive plough; hence, the role of the god in ensuring a successful crop.

Depicts a powerful figure that is part human (body) and part animal (claws, fangs); the god of the temple complex.

Head of snakes and a face of a jaguar.

Eyebrows terminate in snakes.

Flat relief; designs in a curvilinear pattern.

15 feet tall.

Function

Served as a cult figure.

Center of pilgrimage; however, few had access to the Lanzón Stone.

Modern scholars hypothesize that the stone acted as an oracle; hence a point of pilgrimage.

New studies show the importance of acoustics in the underground chamber.

Image

➼ Nose Ornament

Details

hammered gold alloy

Found in Cleveland Museum of Art

Form

Worn by males and females under the nose.

Held in place by the semicircular section at the top.

Two snake heads on either end.

Function: Transforms the wearer into a supernatural being during ceremonies.

Context

Elite men and women wore the ornaments as emblems of their ties to the religion and eventually were buried with them.

The Chavín religion is related to the appearance of the first large-scale precious metal objects; revolutionary new metallurgical process.

Technical innovations express the “wholly other” nature of the religion.

Image

Mayan Art

Mayan sculpture is distinctive due to the Mayan concept of beauty, featuring an arching brow and continuous bridge between forehead and nose.

Head braces were used by the wealthy to create this symbol of beauty.

Mayan sculpture typically features long, narrow faces with full lips and elaborate costumes made of feathers, jade, and jaguar skin.

Relief sculpture was preferred for narrative art with crisp outlines and little attention given to modeling.

Mayan sculpture is commonly found on architectural monuments such as lintels, facades, and jambs.

The chacmool, a half-sitting and half-lying figure with a plate on its stomach, is a common Mayan sculpture.

Mayan pyramids are accompanied by grand temples with narrow and tall interiors, accentuated by long roof combs.

➼ Yaxchilán

Details

725 CE

limestone

Found in Chiapas, Mexico

Function

City set on a high terrace; plaza surrounded by important buildings.

Flourished c. 300–800 C.E.

➼ Structure 40

Details

Overlooks the main plaza.

Three doors lead to a central room decorated with stucco.

Roof remains nearly intact, with a large roof comb (ornamented stone tops on roofs).

Corbel arch interior.

Patronage: Built by ruler Bird Jaguar IV for his son, who dedicated it to him.

Image

➼ Lintel 25, Structure 23

Details

Overlooks the main plaza.

Three doors lead to a central room decorated with stucco.

Roof remains nearly intact, with a large roof comb (ornamented stone tops on roofs).

Corbel arch interior.

Form and Content

The lintel was originally set above the central doorway of Structure 23 as a part of a series of three lintels.

Lady Xook (bottom right) invokes the Vision Serpent to commemorate her husband’s rise to the throne.

The Vision Serpent has two heads: one has a warrior emerging from its mouth, and the other has Tlaloc, a war god.

She holds a bowl with bloodletting ceremonial items: stinging spine and bloodstained paper; she runs a rope with thorns through her tongue.

She burns paper on a dish as a gift to the netherworld.

The depicted ritual was conducted to commemorate the accession of Shield Jaguar II to the throne.

Function

Lintels intended to relay a message of the refoundation of the site—there was a long pause in the building’s history.

Shield Jaguar’s building program throughout the city may have been an attempt to reinforce his lineage and his right to rule.

Context

The building is dedicated to Lady Xook, Shield Jaguar II’s wife.

The inscription is written as a mirror image—extremely unusual among Mayan glyphs; uncertain meaning, perhaps indicating she had a vision from the other side of existence and she was acting as an intercessor or shaman.

The inscription names the protagonist as Shield Jaguar II.

Bloodletting is central to the Mayan life. When a member of the royal family sheds his or her blood, a portal to the netherworld is opened and gods and spirits enter the world.

Theory: Some scholars suggest that the serpent on this lintel and elsewhere depicts an ancestral spirit or founder of the kingdom.

Image

➼ Structure 33

Details

Overlooks the main plaza.

Three doors lead to a central room decorated with stucco.

Roof remains nearly intact, with a large roof comb (ornamented stone tops on roofs).

Corbel arch interior.

Form

Restored temple structure.

Remains of roof comb with perforations.

Three central doorways lead to a large single room.

Corbel arch interior.

Image

Ancient Puebloans

The Anasazi culture was referred to as "ancient ones" or "ancient enemies" in Navajo language.

Anasazi is the name used for ancient puebloans known for their detailed pueblos made of local materials.

Pueblos were made with a core of rubble and mortar, faced with polished stone veneer.

The size of the overall superstructure was determined by the thickness of the base walls, with some pueblos reaching five or six stories tall.

All pueblos had a defined plaza that served as the religious and social center of the complex.

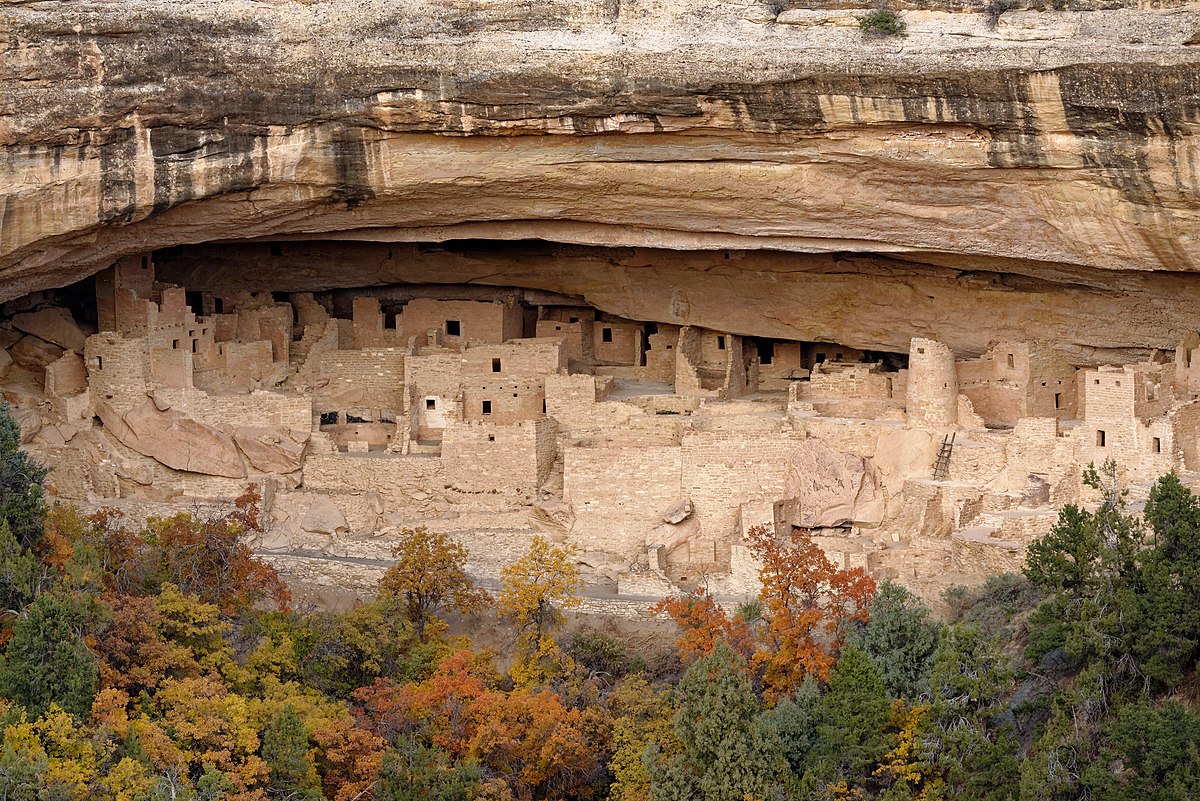

➼ Mesa Verde Cliff Dwellings

Details

Ancestral Puebloan (Anasazi)

450–1300 C.E.

Sandstone

Found in Montezuma County, Colorado

Form

The top ledge houses supplies in a storage area; cool and dry area out of the way; accessible only by ladder.

Each family received one room in the dwelling.

Plaza placed in front of the abode structure; kivas face the plaza.

Function

The pueblo was built into the sides of a cliff, housed about one hundred people.

Clans moved together for mutual support and defense.

Context

Farming done on the plateau above the pueblo; everything had to be imported into the structure; water seeped through the sandstone and collected in trenches near the rear of the structure.

Low winter sun penetrated the pueblo; high summer sun did not enter the interior and therefore it stayed relatively cool.

Inhabited for two hundred years; probably abandoned when the water source dried up.

Image

Mississippian Art

Population growth occurred due to increased agriculture and sustained communities in fertile areas.

Eastern Native Americans were known for their mound-building and created numerous earthworks, some of which still exist today.

City-states like Cahokia in Illinois were governed by huge mound complexes.

Other mounds, like the Great Serpent Mound, were built in shapes of uncertain significance.

Archaeologists are puzzled by many of these mounds, as they could only be fully appreciated from the air or a high vantage point that the mound builders did not have.

➼ Great Serpent Mound

Details

Mississippian (Eastern Woodlands)

c. 1070 C.E.

earthwork/effigy mound

Found in Adams County, southern Ohio

Context

Many mounds were enlarged and changed over the years, not built in one campaign.

Effigy mounds popular in Mississippian culture.

Associated with snakes and crop fertility.

There are no burials associated with this mound, though there are burial sites nearby.

Theories

Influenced by comets? Astrological phenomenon? Head pointed to summer solstice sunset?

Theory that it could be a representation of Halley’s Comet in 1066.

Rattlesnake as a symbol in Mississippian iconography; could this play a role in interpreting this mound?

Image

Aztec Art

Aztec art is best known for its abundance of gold jewelry, as well as intricately carved jade and turquoise pieces.

Aztec religion was characterized by violent ceremonies that involved blood-letting.

This aggressive nature of their religion is reflected in the art, with horrifying stone sculptures of deities such as Coyolxauhqui featuring human remains from sacrifices.

➼ Templo Mayor (Main Temple)

Details

1375–1520

Stone

Found in Tenochtitlán, Mexico City, Mexico

Form

Pyramids built one atop the other so that the final form encases all previous pyramids; seven building campaigns.

Pyramids have a step-like series of setbacks; not the smooth-surfaced pyramids seen in Egypt.

Characterized by four huge flights of very vertical steps leading to temples placed on top.

Function

Tenochtitlán was laid out on a grid; city seen as the center of the world.

The temple structures on top of each pyramid were dedicated to and housed the images of the two important deities.

Context

Two temples atop a pyramid, each with a separate staircase:

North: dedicated to Tlaloc, god of rain, agriculture.

South: dedicated to Huitzilopochtli, god of sun and war.

At the spring and autumn equinoxes, the sun rises between the two.

Large braziers put on top where the sacred fires burned.

Temple structures housed images of the deities.

Temples begun in 1375; rebuilt six times; destroyed by the Spanish in 1520.

The destruction of this temple and reuse of its stones by the Spanish asserted a political and spiritual dominance over the conquered civilization.

Image

➼ Coyolxauhqui “She of the Golden Bells”

Details

1469

volcanic stone

Found in Museum of the Templo Mayor, Mexico City

Form

Circular relief sculpture.

Once brilliantly painted.

So called because of the bells she wears as earrings.

Context

Coyolxauhqui and her many brothers plotted the death of her mother, Coatlicue, who became pregnant after tucking a ball of feathers down her bosom.

When Coyolxauhqui chopped off Coatlicue’s head, a child, Huitzilopochtli, popped out of the severed body fully grown and dismembered Coyolxauhqui, who fell dead at the base of the shrine.

This stone represents the dismembered moon goddess, Coyolxauhqui, who is placed at the base of the twin pyramids of Tenochtitlán.

Aztecs sacrificed people and then threw their dismembered remains down the steps of the temple as Huitzilopochtli did to Coyolxauhqui.

Aztecs similarly dismembered enemies and threw them down the stairs of the great pyramid to land on the sculpture of Coyolxauhqui.

A relationship was established between the death and decapitation of Coyolxauhqui with the sacrifice of enemies at the top of Aztec pyramids.

Image

➼ Calendar Stone

Form: Made of basalt.

Context

Aztecs felt they needed to feed the sun god human hearts and blood.

A tongue in the center of the stone coming from the god’s mouth is a representation of a sacrificial flint knife used to slash open the victims.

Circular shape reflects the cyclic nature of time.

Two calendar systems, separate but intertwined.

Calendars synced every fifty-two years in a time of danger, when the Aztecs felt a human sacrifice could ensure survival.

Image

➼ Olmec-style Mask

Form: Made of jadeite.

Context

Found on the site; actually a much older work executed by the Olmecs.

Olmec works have a characteristic frown on the face; pugnacious visage; baby face; a cleft in the center of the head carved from greenstone.

Shows that the Aztecs collected and embraced artwork from other cultures, including early Mexican cultures such as the Olmec and Teotihuacán.

Shows that the Aztecs had a wide-ranging merchant network that traded historical items.

Image

➼ Ruler’s Feather Headdress

Details:

1428–1520

feathers (quetzal and blue cotinga) and gold

Found in Museum of Ethnology, Vienna

Form

Made from 400 long green feathers, the tails of the sacred quetzal birds; male birds produce only two such feathers each.

The number 400 symbolizes eternity.

Function

Ceremonial headdress of a ruler.

Part of an elaborate costume.

Context

Only known Aztec feather headdress in the world.

Feathers indicate trading across the Aztec Empire.

Headdress possibly part of a collection of artifacts given by Motechuzoma (Montezuma) to Cortez for Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire.

Current dispute over ownership of the headdress; today it is housed in the Museum of Ethnology in Vienna, Austria.

Image

Inkan Art

Inkan architecture is remarkable for constructing cities in extremely challenging locations.

Ashlar masonry with perfectly grooved and fitted stones was commonly used in Inkan buildings.

The stones have slightly beveled edges that emphasize the joints and buildings tend to taper upward like a trapezoid.

The Inka Empire spanned Chile to Colombia and had an organized system of roads for efficient communication.

The Inka did not have a written language, so archaeology is a key source of knowledge about their civilization.

➼ Maize cobs

Details

c. 1440–1533

sheet metal/repoussé, metal alloys

Found in Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Technique and Form

Repoussé technique.

Hollow metal object.

Life-size.

Function

May have been part of a garden in which full-sized metal sculptures of maize plants and other items were put in place alongside actual plants in the Qorinkancha garden.

May have been used to ensure a successful harvest.

Context

Maize was the principal food source in the Andes.

Maize was celebrated by having sculptures fashioned out of sheet metal.

Black maize was common in Peru; oxidized silver reflects that.

Image

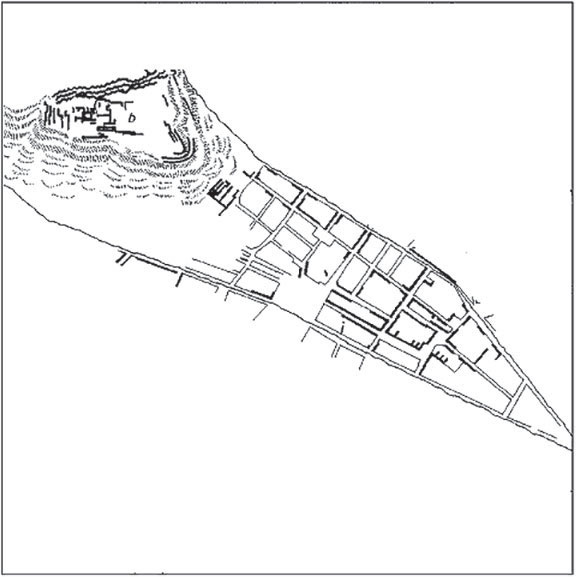

➼ City of Cusco

Details

C. 1440

Found in Peru

Form

In the shape of the puma, a royal animal.

Modern plaza is in the place where the puma’s belly would be.

Head, a fortress; heart, a central square.

Function: Historic capital of the Inka Empire.

Image

➼ Qorikancha

Details

main temple, church, and convent of Santo Domingo

c. 1440, convent added 1550–1650

Andesite

Found in Cusco, Peru

Form

Ashlar masonry; carefully grooved and beveled edges of the stone fit together in a puzzle-like formation.

Slight spacing among stones allows movement during earthquakes.

Walls taper upward; examples of Inkan trapezoidal architecture.

Temple displays Inkan use of interlocking stonework of great precision.

Original exterior walls of the temple were decorated in gold to symbolize sunshine.

Spanish chroniclers insist that the walls and floors of the temple were covered in gold.

Function

Qorikancha: golden enclosure; once was the most important temple in the Inkan world.

Once was an observatory for priests to chart the skies.

Context

The location is important; placed at the convergence of the four main highways and connected to the four districts of the empire; the temple cemented the symbolic importance of religion, uniting the divergent cultural practices that were observed in the vast territory controlled by the Inkas.

Remains of the Inkan Temple of the Sun form the base of the Santo Domingo convent built on top.

Image

➼ Walls at Saqsa Waman (Sacsayhuaman)

Details

c. 1440

Sandstone

Found in Peru

Form

Ashlar masonry.

Ramparts contain stones weighing up to seventy tons, brought from a quarry two miles away.

Context: Complex outside the city of Cusco, Peru, at the head of the puma-shaped plan of the city.

Image

➼ Machu Picchu

Details

1450–1540

Granite

Found in Central Highlands, Peru

Form

Buildings built of stone with perfectly carved rock rendered in precise shapes and grooved together; thatched roofs.

Outward faces of the stones were smoothed and grooved.

Two hundred buildings, mostly houses; some temples, palaces, and baths, and even an astronomical observatory; most in a basic trapezoidal shape.

Entryways and windows are trapezoidal.

People farmed on terraces.

Function

Originally functioned as a royal retreat.

The estate of fifteenth-century Inkan rulers.

So remote that it was probably not used for administrative purposes in the Inkan world.

Peaceful center: many bones were uncovered, but none of them indicate war-like behavior.

Image

➼ Observatory in Machu Picchu

Details

1450–1540

Granite

Found in Peru

Form

Ashlar masonry.

Highest point at Machu Picchu.

Function

Used to chart the sun’s movements; also known as the Temple of the Sun.

Left window: sun shines through on the morning of the winter solstice.

Right window: sun shines through on the morning of the summer solstice.

Devoted to the sun god.

Image

➼ Intihuatana Stone in Machu Picchu

Context

Intihuatana means “hitching post of the sun”; aligns with the sun at the spring and the autumn equinoxes, when the sun stands directly over the pillar and thus creates no shadow.

Inkan ceremonies held in concert with this event.

Image

➼ All-T’oqapu Tunic

Details

1450–1540

camelid fiber and cotton

Found in Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.

Form

Rectangular shape; a slit in the center is for the head; then the tunic is folded in half and the sides are sewn for the arms.

The composition is composed of small rectangular shapes called t’oqapu.

Individual t’oqapu may be symbolic of individuals, events, or places.

This tunic contains a large number of t’oqapu.

Function

Wearing such an elaborate garment indicates the status of the individual.

May have been worn by an Inkan ruler.

Technique

Woven on a backstrap loom.

One end of the loom is tied to a tree or a post and the other end around the back of the weaver.

The movement of the weaver can create alternating tensions in the fabric and achieve different results.

Context

Exhibits Inkan preference for abstract designs, standardization of designs, and an expression of unity and order.

Finest textiles made by women, a highly distinguished art form; this tunic has a hundred threads per square centimeter.

Image

North American Indian Art

Local materials used for North American art: wood, clay, plant fibers, wool, and hides.

Nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples created geometric designs on ceramics and highly decorated fabric with beading and weaving.

Plains Indians illustrated hides to relate myths and events.

European settlers brought new media and a curiosity about native art forms.

Native American artists adapted traditional art forms to new media.

European settlers acted as collectors and patrons for native American works.

Native American artists began serving an emerging tourist industry that appreciated their artistry.

Examples of native American artists: Cadzi Cody in hide painting and Maria Martínez in ceramics.

➼ Bandolier Bag

Details

From Lenape (Delaware tribe, Eastern Woodlands)

c. 1850

beadwork on leather

Found in Museum of the American Indian

Form

The bandolier bag has a large, heavily beaded pouch with a slit on top.

The bag was held at hip level with strap across the chest.

The bag was constructed of trade cloth: cotton, wool, velvet, or leather.

Function

It was made for men and women; objects of prestige.

They were made by women.

Functional and beautiful; acted also as a status symbol as part of an elaborate garb.

Bandolier bags are still made and worn today.

Context

Beadwork not done in the Americas before European contact.

Beads and silk ribbons were imported from Europe.

The bags contain both Native American and European motifs.

Image

➼ Transformation Mask

Details

From Kwakwaha’wakw, Northwest Coast of Canada

late 19th century

wood, paint, and string

Found in Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, France

Form: The mask has a birdlike exterior face; when opened, it reveals a second human face on the interior.

Function

The masks were worn by native people of the Pacific. Northwest, centered on Vancouver Island.

They were worn over the head as part of a complete body costume.

Context

During a ritual performance, the wearer opens and closes the transformation mask using strings.

At the moment of transformation, the performer turns his back to the audience to conceal the action and heighten the mystery.

Opening the mask reveals the face of an ancestor; there is an ancestral element to the ceremony.

Although these masks could be used at a potlatch, most often they were used in winter initiation rites ceremonies.

The ceremony is accompanied by drumming and takes place in a “big house.”

Masks are highly prized and often inherited.

Image

➼ Hide Painting of the Sun Dance

Details

Attributed to Cotsiogo (Cadzi Cody)

Painted elk hide, Eastern Shoshone, Wind River Reservation, Wyoming,

c. 1890–1900,

Found in Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York

Content

Depicts traditional aspects of the Plains people’s culture that were nostalgic rather than practical: bison hunted with bow and arrow—nomadic hunting gone; bison nearly extinct.

Hide paintings mark past events.

Bison considered to be gifts from the Creator.

Horses, in common use around 1750, liberated the Plains people.

Teepee: made of hide stretched over poles:

Exterior poles reach the spirit world or sky.

Fire represents the heart.

The doorway faces east to greet the new day.

The sun dance was conducted around a bison head, and was outlawed by the U.S. government; viewed as a threat to order.

The sun dance involved men dancing, singing, preparing for the feast, drumming, and constructing a lodge. They honored the Creator deity for the bounty of the land.

The warrior’s deeds were celebrated on the hide.

Function

Worn as a robe over the shoulders of the warrior.

Perhaps a wall hanging.

Context

Depicts biographical details; personal accomplishments; heroism; battles.

Men painted hides to narrate an event.

Eventually, painted hides were made for European and American markets; tourist trade.

Used paint and dyes obtained through trade.

Image

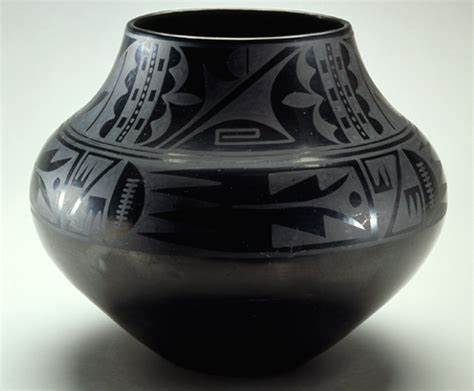

➼ Black-on-black Ceramic Vessel

Details

By Maria Martínez and Julian Martínez

From Tewa, Puebloan, San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico, mid-20th century

blackware ceramic

Found in Smithsonian Museum of American Art, Washington, D.C..

Form

Black-on-black vessel.

Highly polished surface.

Contrasting shiny black and matte black finishes.

Exceptional symmetry; walls of even thickness; surfaces free of imperfections.

Function

Comes from the thousand-year-old tradition of pottery making in the Southwest.

Maria Martínez preferred making pots using a new technique that rendered a vessel lightweight, less hard, and not watertight, as traditional pots were; this kind of vessel reflected the market shift away from utilitarian vessels to decorative objects.

Technique

Used a mixture of clay and volcanic ash.

The surface was scraped to a smooth finish with a gourd tool and then polished with a stone.

Julian Martínez painted designs with a liquid clay that yielded a matte finish in contrast with the high shine of the pot itself.

Context

At the time of production, pueblos were in decline; modern life was replacing traditional life.

Artists’ work sparked a revival of pueblo techniques.

Maria Martínez, the potter, developed and invented new shapes beyond the traditional pueblo forms.

Julian Martínez, the painter of the pots, revived the use of ancient mythic figures and designs on the pots.

Reflects an influence of Art Deco designs popular at the time.

Image

Knowt

Knowt