Chapter 17 - Wages & unemployment

3 important labor market trends

Over a long period, average real wages have risen substantially both in the United States and in other industrialized countries.

Despite the long-term upward trend in real wages, real wage growth has been stagnant in the United States since the early 1970s. Employment also grew substantially from the 1970s through the 1990s. However, over the last de cade the share of the working-age population either employed or actively looking for work has dramatically decreased from its peak in 2000.

In the United States, wage inequality has increased dramatically in recent decades. The real wages of most unskilled workers have actually declined, while the real wages of skilled and educated workers have continued to rise.

Supply and demand in the labor market

Diminishing returns to labor: if the amount of capital and other inputs in use is held constant, then the greater the quantity of labor already employed, the less each additional worker adds to production.

Demand for labor

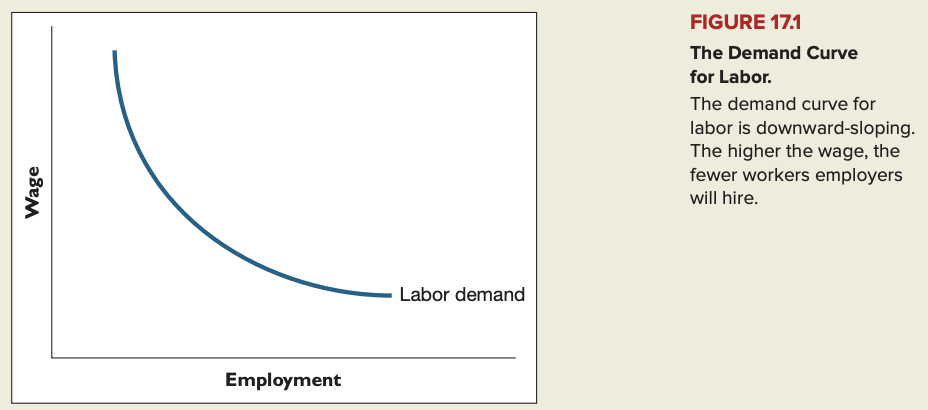

- The extra production gained by adding one more worker is the marginal product of that worker. The value of the marginal product of a worker is that worker's marginal product times the price of the firm's output. A firm will employ a worker only if the worker's value of marginal product, which is the same as the extra revenue the worker generates for the firm, exceeds the real wage that the firm must pay. The lower the real wage, the more workers the firm will find it profitable to employ. Thus, the labor demand curve, like most demand curves, is downward-sloping.

- For a given real wage, any change that increases the value of workers' marginal products will increase the demand for labor and shift the labor demand curve to the right. Examples of factors that increase labor demand are an increase in the price of workers' output and an increase in productivity.

Supply of labor

- An individual is willing to supply labor if the real wage that is offered is greater than the opportunity cost of the individual's time. Generally, the higher the real wage, the more people are willing to work. Thus, the labor supply curve, like most supply curves, is upward-sloping.

- For a given real wage, any factor that increases the number of people available and willing to work increases the supply of labor and shifts the labor supply curve to the right. Examples of factors that increase labor supply include an increase in the working-age population or an increase in the share of the working-age population seeking employment.

Unemployment and the unemployment rate

Labor force: total number of employed and unemployed people in the economy.

Unemployment rate: number of unemployed people divided by the labor force.

Participation rate: percentage of the working age population in the labor force (that is, the percentage that is either employed or looking for work).

Unemployment spell: period during which an individual is continuously unemployed.

Types of unemployment and their costs

Frictional unemployment: short-term unemployment associated with the process of matching workers with jobs.

Structural unemployment: long-term and chronic unemployment that exists even when the economy is producing at a normal rate.

Cyclical unemployment: extra unemployment that occurs during periods of recession.