Unit 1: Introduction to Biochemistry

Biochemistry

Biochemistry is the branch of science that studies the chemical nature and behaviour of living matter. It focuses on understanding life at a molecular level and explains biological processes in terms of chemistry by applying chemical principles to explain processes like enzyme catalysis, and energy production. It focuses on:

Metabolic Reactions

Processes that sustain life, including:

Digestion

Excretion

Respiration

Biomolecular Analysis

The study and analysis of biomolecules such as proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, and nucleic acids.

Cellular Component Characterization:

Investigating the structural and functional components of cells.

Chemistry of Biological Phenomena:

Applying chemical principles to explain processes like enzyme catalysis, energy production, and signal transduction in living organisms.

Historical Context

The term "Biochemistry" was introduced by Carl Neuberg, a German chemist, in 1903.

Early studies in biochemistry can be traced back to the 1500s when alchemists and early scientists began exploring the chemical nature of life.

Branches of Biochemistry

Biochemistry can be broadly divided into two main branches:

Descriptive Biochemistry

Focuses on the qualitative and quantitative characterization of cellular components, including biomolecules like:

DNA

Proteins

Lipids

Carbohydrates

Dynamic Biochemistry

Investigates the mechanisms of action involving cellular components, such as:

Enzymatic reactions

Metabolic pathways

Signal transduction [process of transferring a signal throughout an organism]

Newer Disciplines

Enzymology

Endocrinology

Clinical Biochemistry

Molecular Biology

Biotechnology

Pharmacological Biochemistry

Nutrition

Fermentation Technology

Importance of Biochemistry

1. Understanding the Cause of Diseases

Biochemistry provides insight into how diseases develop by identifying molecular and cellular abnormalities.

Examples: Genetic disorders, enzyme deficiencies, and metabolic imbalances.

2. Composition of Living Cells and Biomolecules

It helps determine the chemical composition of cells and the molecules they contain, such as:

Proteins

Lipids

Carbohydrates

Nucleic acids

3. Localization and Structure of Biomolecules

Identifies where biomolecules are located in the cell (e.g., nucleus, cytoplasm, or cell membrane).

Examines the structure of cells and biomolecules, which is critical for understanding their functions.

4. Function of Biomolecules and Structure-Function Relationships

Explores how the structure of a biomolecule determines its function.

Example: The folding of proteins affects their enzymatic activity or ability to bind to other molecules

5. Sources of Biochemicals in Cells

Investigates the origin of biochemicals, which can come from:

Nutrients obtained through diet.

Cellular biosynthesis, where cells produce necessary molecules internally.

6. Biosynthesis, Biodegradation, and Function

Examines how biomolecules are synthesized, used, and degraded within the cell.

Links the synthesis of new molecules to the degradation of old ones in maintaining cell function.

7. Maintaining Homeostasis

Studies how the concentration of cellular molecules is regulated during metabolic pathways and reactions.

Ensures a balance between the production and consumption of energy and resources within the cell.

Chemical Composition of Humans

The human body is primarily composed of the following elements and molecules:

Major Elements:

Oxygen (O)

Carbon (C)

Hydrogen (H)

Nitrogen (N)

Calcium (Ca)

Phosphorus (P)

Molecular Composition:

Water (H₂O): The most abundant compound in the body.

Proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids make up the majority of the dry mass.

Biological Importance of Water

Molecular Composition: H₂O (one oxygen atom covalently bonded to two hydrogen atoms).

Essential for Life: No known organism can survive without water.

Abundance: Water is the most abundant substance on Earth.

Proportion of Water in Organisms

Water constitutes ≥70% of the body weight in most organisms. In obese individuals, water content is reduced to 45–60% due to higher fat content.

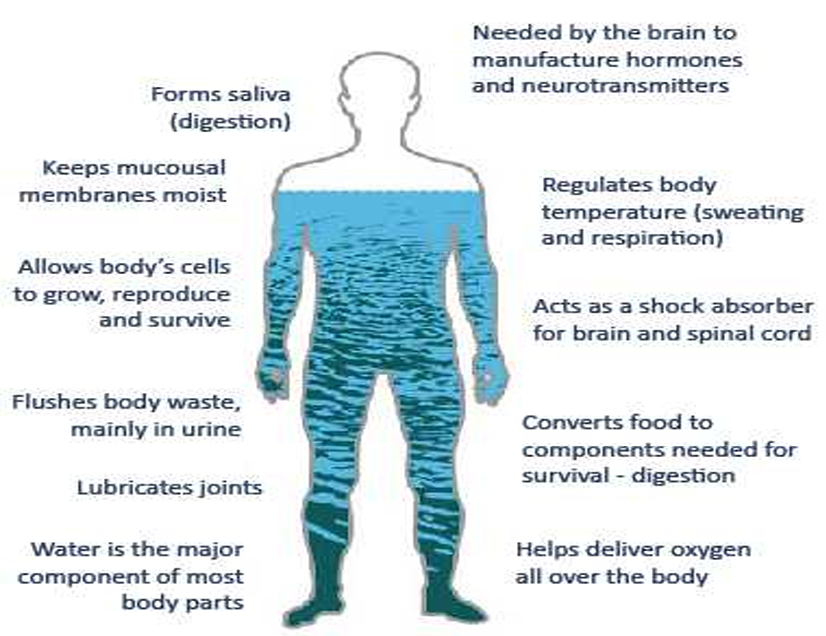

Role of Water in the Human Body:

Temperature Regulation: Maintains body temperature through the expulsion of water from the skin (sweat) and lungs (breathing).

Water Loss

10% loss: This can lead to serious consequences.

20% loss: Often fatal.

Water Balance

Refers to the equilibrium between water intake (from drinking, food, and metabolic water) and output (through sweat, urine, and respiration).

Metabolic Water Production

Water generated during the oxidation of macromolecules:

100g of Fat: 107g of water.

100g of Carbohydrates: 55g of water.

100g of Proteins: 41g of water.

Imbalances in Water Levels:

Dehydration:

Occurs when output > intake.

This is particularly severe in infants as they have a small water pool that depletes rapidly.

Edema:

Accumulation of water in tissues.

Commonly observed in conditions like Kwashiorkor (sugar babies) in malnourished children.

Overview of Chemical Composition of the Body

Versatility of Carbon Compounds

Carbon compounds are highly versatile and can polymerize into large, complex structures known as macromolecules.

Macromolecules and Polymers

Macromolecules: Large molecules formed by the joining of smaller units.

Polymers: Long chains formed by connecting smaller organic molecules (monomers) through condensation reactions.

Different Properties from Monomers:

Polymers often exhibit properties that are distinct from their individual monomers.

Example: Glucose (a carbohydrate monomer) is more soluble and sweeter than starch (a carbohydrate polymer).

Example: Individual nucleotides [adenine, thymine, cytosine, guanine] are simple molecules that do not store genetic information. When polymerized into DNA, they form the genetic code that carries hereditary information.

NB

Monomer: A small molecule that acts as a building block for larger molecules (e.g., glucose, amino acids).

Polymer: A large molecule made up of repeating monomers linked together (e.g., starch, proteins).

Macromolecule: A very large molecule, often made of polymers, essential for biological processes (e.g., DNA, cellulose).

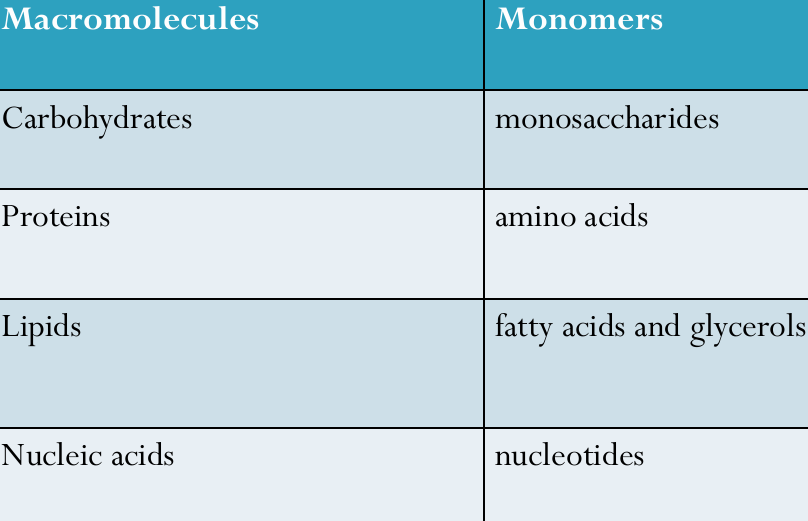

Biological Macromolecules

The four major organic macromolecules are:

Carbohydrates

Proteins

Lipids

Nucleic Acids

Organic Compounds Overview

Carbohydrates

Building Block: Monosaccharides (simple sugars).

Types:

Monosaccharides: Glucose, fructose, galactose.

Disaccharides: Lactose, maltose, sucrose.

Polysaccharides: Starch, cellulose, chitin, inulin, pectin.

Functions:

Energy storage (e.g., glucose for quick energy, starch for long-term energy).

Physical structure (e.g., cellulose in plant cell walls, chitin in fungal cell walls and exoskeletons).

Proteins

Building Block: Amino acids.

pes: Antibodies; viral surfaces, flagella; pili

Functions:

Enzymatic activity (e.g., enzymes catalyze biochemical reactions).

Structural roles (e.g., keratin, collagen).

Defence mechanisms (e.g., antibodies).

Movement (e.g., flagella and pili on bacterial cells).

Lipids

Building Blocks: Fatty acids and glycerol.

Types:

Triglycerides: Fat and oil for energy storage, thermal insulation, and shock absorption.

Phospholipids: Foundation for cell membranes (e.g., plasma membrane).

Steroids: Cholesterol and hormones for membrane stability and signalling.

Functions:

Energy storage.

Thermal insulation.

Shock absorption.

Structural components of cell membranes.

Nucleic Acids

Building Blocks: Ribonucleotides (RNA) and deoxyribonucleotides (DNA).

Functions:

Inheritance (e.g., DNA stores genetic information).

Protein synthesis (e.g., RNA translates genetic information into proteins).

Examples: DNA, RNA

Carbohydrates

Also called sugars or saccharides.

Composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) in a typical ratio of (CH₂O)n.

Plants contain ~30% carbohydrates, whereas animals contain only ~1%.

Functions of Carbohydrates

Primary Source of Energy

The brain relies exclusively on glucose for energy.

Carbohydrates are metabolized to ATP for cellular processes.

Structural Component

Forms the sugar backbone of DNA (deoxyribose) and RNA (ribose), enabling flexibility and storage of genetic material.

Major component of bacterial and plant cell walls (e.g., cellulose in plants, peptidoglycan in bacteria).

Metabolic Role

Provides carbon skeletons for various biochemical reactions.

Cell Communication and Recognition

Glycoproteins and glycolipids on cell surfaces aid in cell-cell recognition.

Example: Sperm-egg recognition during fertilization.

Digestive Health

Dietary fibers (e.g., cellulose) promote bowel movement and digestive health.

Protein

The most abundant intracellular macromolecule

The majority of protein mass is found in skeletal muscle

Composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), nitrogen (N), and small amounts of sulfur (S) → CHONs (of the 20 amino acids only two contain sulphur. Those are: cysteine and methionine

Sulfur content: Typically 0.5 - 2.0%, except insulin, which contains 3.4% sulfur.

Functions of Proteins

Catalysis

Act as biological catalysts (enzymes) to speed up biochemical reactions.

Example: Amylase (breaks down starch into maltose).

Transport & Carrier Molecules

Transport small molecules and ions within the body.

Example: Hemoglobin transports oxygen in red blood cells.

Structural Support

Provide high tensile strength for skin and bones.

Example: Collagen (a fibrous protein in connective tissues).

Immune Function

Proteins play a role in immunoregulation (antibodies).

Example: Immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, IgM) help fight infections.

Nerve Signal Transmission

Receptor proteins facilitate the transmission of nerve impulses.

Example: Acetylcholine receptors in neurons.

Muscle Contraction & Movement

Major components of muscles (actin and myosin).

Example: Myosin and actin filaments drive muscle contractions.

Lipids

Structure of Lipids

A heterogeneous group of molecules including fats, oils, and waxes.

Composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) (CHOs).

Insoluble in water (hydrophobic) but soluble in organic solvents like ether and benzene.

Types of Lipids

Simple Lipids

Fats & Oils (Triglycerides) → Composed of glycerol + 3 fatty acids.

Example: Butter (saturated fat), Olive oil (unsaturated fat).

Compound Lipids

Phospholipids → Composed of glycerol, two fatty acids, a phosphate group, and an R group.

Example: Lecithin (found in cell membranes).

Steroids

Four fused carbon rings with various functional groups.

Examples: Cholesterol (membrane stability), Testosterone & Estrogen (hormones).

Waxes

Long-chain fatty acids + alcohols.

Example: Beeswax, earwax (cerumen), cuticle of plants.

Functions of Lipids

Energy Storage

Store more energy per gram than carbohydrates or proteins.

Example: Adipose tissue stores fat for long-term energy use.

Thermal Insulation & Protection

Stored under the skin to maintain body temperature.

Example: Blubber in whales & seals.

Structural Components of Cells

Phospholipids form the lipid bilayer of cell membranes.

Example: Plasma membrane of all cells.

Hormone Production & Metabolic Regulation

Steroids function as hormones (e.g., estrogen, testosterone).

Regulate metabolism, immune response, and reproduction.

Waterproofing & Lubrication

Waxes help prevent water loss in plants & animals.

Example: Cuticle on leaves, wax in ears.

Nucleic Acids

Structure of Nucleic Acids

Composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P).

Monomers: Nucleotides, consisting of:

A pentose sugar (deoxyribose in DNA, ribose in RNA).

A phosphate group.

A nitrogenous base (Adenine, Thymine/Uracil, Cytosine, Guanine).

Types of Nucleic Acids

DNA (Deoxyribonucleic Acid)

Double-stranded molecule.

Stores genetic information and passes it from one generation to another.

Found mainly in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells.

RNA (Ribonucleic Acid)

Single-stranded molecule.

Helps in protein synthesis by carrying genetic instructions from DNA.

Found in both the nucleus and cytoplasm.

Viruses and Nucleic Acids

Viruses contain either DNA or RNA, but never both.

Example: HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) contains RNA as its genetic material.

Corona Virus is also a RNA virus.

DNA Viruses: small pox ad herpes

Functions of Nucleic Acids

Storage of Genetic Information

DNA contains genes that code for proteins.

Protein Synthesis

RNA (mRNA, tRNA, rRNA) helps in the production of proteins.

Energy Transfer

ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate), a nucleotide, stores and transfers energy in cells.

Metabolic Regulation

Some nucleotides form co-enzymes needed for biochemical reactions (e.g., NAD+, FAD).

Functional Group

(picturessss)

Covalent vs. Non-Covalent Interactions

Covalent and non-covalent interactions play crucial roles in determining the structure, stability, and function of biological molecules.

Covalent Interactions (Strong Bonds)

Definition: Covalent bonds form when two atoms share electrons.

Strength: Strong, requiring significant energy to break.

Examples:

Peptide bonds in proteins.

Phosphodiester bonds in nucleic acids (DNA, RNA).

Glycosidic bonds in carbohydrates.

Non-Covalent Interactions (Weak Bonds)

Non-covalent interactions are weaker than covalent bonds but are essential for biological processes like protein folding, enzyme-substrate binding, and DNA structure formation.

(a) Hydrogen Bonds

Definition: A weak bond between a hydrogen atom (bound to N, O, or F) and another electronegative atom.

Examples:

Stabilization of DNA double helix (A-T, G-C base pairing).

Secondary structures of proteins (alpha-helix and beta-sheet).

(b) Ionic Interactions (Electrostatic Forces)

Definition: Attraction between oppositely charged ions or groups.

Examples:

Salt bridges in protein folding.

Binding of charged substrates to enzymes.

(c) Van der Waals Interactions

Definition: Weak attractions due to temporary dipoles in molecules.

Examples:

Molecular packing in lipid membranes.

Weak interactions between non-polar amino acids in proteins.

(d) Hydrophobic Interactions

Definition: Non-polar molecules tend to aggregate in an aqueous environment to minimize contact with water.

Examples:

Membrane formation (hydrophobic tails of phospholipids cluster together).

Protein folding (hydrophobic core formation).

Hydrogen Bonding

Hydrogen bonding is a strong intermolecular force that occurs when a hydrogen atom, covalently bonded to a highly electronegative atom (N, O, or F), interacts with another electronegative atom.

Key Features of Hydrogen Bonding:

Stronger than other intermolecular forces (like Van der Waals forces) but weaker than covalent bonds.

Increases the melting and boiling points of substances.

Found in many biological and chemical systems.

Examples of Hydrogen Bonding in Biology & Chemistry

Water (H₂O):

Each water molecule forms hydrogen bonds with up to four other molecules.

This explains high surface tension, high boiling point, and ice floating on water.

DNA Double Helix:

Hydrogen bonds between base pairs (A-T, G-C) stabilize the structure.

A-T has 2 hydrogen bonds, while G-C has 3 hydrogen bonds, making G-C pairs more stable.

Proteins (Secondary Structure):

Hydrogen bonding between peptide bonds stabilizes α-helices and β-sheets.

Example: Keratin (hair, nails) and collagen (connective tissue).

Ethanol (C₂H₅OH) & Other Alcohols:

The O-H group forms hydrogen bonds, making alcohols more soluble in water.

Ammonia (NH₃):

Hydrogen bonds make ammonia highly soluble in water.

Ionic Interactions

Ionic interactions (also called ionic bonds, salt linkages, salt bridges, or ion pairs) occur due to the electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions.

Key Features of Ionic Interactions:

Strength: Strongest in a vacuum or nonpolar environment, but weaker in polar solvents like water due to ion solvation.

Role in Stability: Contributes to the stability of biomolecules and biochemical reactions.

Reversible: Unlike covalent bonds, ionic interactions are more easily broken in aqueous environments.

Examples of Ionic Interactions

1. In Salts (NaCl - Table Salt):

Sodium chloride (NaCl) forms when Na⁺ donates an electron to Cl⁻, creating an electrostatic attraction.

In water, NaCl dissolves into Na⁺ and Cl⁻ ions due to water’s polarity.

2. In Proteins (Salt Bridges):

Amino acids with charged side chains (like glutamate (Glu⁻) and lysine (Lys⁺)) form ionic bonds, stabilizing tertiary and quaternary protein structures.

Example: The hemoglobin protein contains salt bridges that help maintain its shape.

3. In DNA (Phosphate Backbone):

The phosphate groups (PO₄³⁻) in DNA interact with positively charged metal ions (e.g., Mg²⁺) or proteins (e.g., histones) to maintain structural integrity.

4. In Cell Membranes (Ion Channels & Transport):

Ion channels regulate movement of charged ions (Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, Cl⁻) across membranes.

Example: Neuronal signaling relies on ionic interactions in sodium-potassium pumps (Na⁺/K⁺ ATPase).

Hydrophobic Interactions

Hydrophobic interactions occur when nonpolar molecules or nonpolar regions of a molecule aggregate together in an aqueous environment rather than dissolving in water.

Key Features of Hydrophobic Interactions:

Water Exclusion: Nonpolar molecules cannot form hydrogen bonds with water, leading to their aggregation.

Entropy Increase: When nonpolar molecules cluster, fewer water molecules are restricted in motion, increasing entropy (disorder), making the system more stable.

Energetic Favorability: Water molecules are normally in motion, and forming rigid structures around nonpolar molecules is energetically unfavorable.

Examples of Hydrophobic Interactions

Cell Membrane Formation (Phospholipid Bilayer)

The hydrophobic tails of phospholipids cluster together, while the hydrophilic heads interact with water.

This drives the formation of the lipid bilayer, a key structure in biological membranes.

Protein Folding & Stability

Hydrophobic amino acids (e.g., leucine, valine) bury themselves inside proteins, away from water, helping proteins achieve their functional 3D structure.

Oil and Water Separation

Oils and fats do not mix with water due to hydrophobic interactions, causing phase separation.

Transport of Lipids in Blood (Lipoproteins)

Hydrophobic lipids (like cholesterol and triglycerides) require lipoproteins (HDL, LDL) to be transported into the bloodstream.

Van der Waals Interactions

Van der Waals interactions are weak non-covalent forces that arise from fluctuations in electron distribution between atoms or molecules, leading to temporary or permanent dipoles. These forces play a crucial role in biological macromolecules, stabilizing proteins, DNA, and membranes.

Types of Van der Waals Forces:

London Dispersion Forces (Weaker)

Dipole-Dipole Forces (Stronger)

London Dispersion Forces (LDFs)

Also known as Induced dipole-induced dipole forces

Characteristics:

Present in all atoms and molecules, both polar molecules (HF) and nonpolar ones CO2). However, dominant intermolecular forces in non-polar molecules eg. F2, Cl2, Br2 and I2 (gases)

Arise due to temporary fluctuations in electron distribution, creating a temporary dipole ( a polarised molecule having a sightly positive pole and a slightly negative pole, the electronic cloud of a neutral atom is distorted for a time being)

Neighbouring atoms induce dipoles in each other, leading to weak attractions. (the temporary induces dipole by disturbing/distorting the electrons in the neighbouring atom.

Strength increases with the size and mass of molecules (larger molecules have more electrons and stronger dispersion forces).

Contributes to the boiling/melting points of noble gases and nonpolar molecules.

Examples:

Noble gases (He, Ne, Ar, Kr, Xe) – Exist as gases due to weak dispersion forces but liquefy at very low temperatures.

Nonpolar molecules (O₂, N₂, CH₄, CO₂, I₂) – Held together in solid or liquid form by dispersion forces.

Lipids in cell membranes – Weak dispersion forces help stabilize membrane structure.

Dipole-Dipole Forces

Also known as permanent dipole interactions

Characteristics:

Occurs only in polar molecules with permanent dipoles.

The positive end of one molecule attracts the negative end of another.

Stronger than London dispersion forces but weaker than ionic or hydrogen bonds.

Contributes to solubility – Polar molecules dissolve in polar solvents (like water).

Examples:

HCl (Hydrogen Chloride) – The partially positive hydrogen of one HCl molecule interacts with the partially negative chlorine of another.

Acetone (CH₃COCH₃) dissolving in water – Acetone is polar and mixes with water due to dipole-dipole attractions.

DNA base stacking – Although hydrogen bonds hold bases together, van der Waals interactions stabilize DNA structure.

Covalent Interaction

Disulfide Bonds

Disulfide bonds (also known as disulfide linkages) are a type of covalent bond formed between two thiol (–SH) groups. These bonds play a critical role in stabilizing the three-dimensional structure of proteins by forming cross-links between different parts of a polypeptide chain or between multiple chains.

How are Disulfide Bonds Formed?

Oxidation Process:

Disulfide bonds are formed when two thiol groups (–SH) from cysteine residues in proteins undergo oxidation.

During this process, two hydrogen atoms are removed, leading to the formation of a covalent bond between the sulfur atoms of the thiol groups, resulting in a –S–S– linkage.

Knowt

Knowt