Chapter 2: Basic Rhetorical Modes

Rhetorical Modes

Rhetorical modes are ways of using language that are intended to have an effect on the audience.

Classification

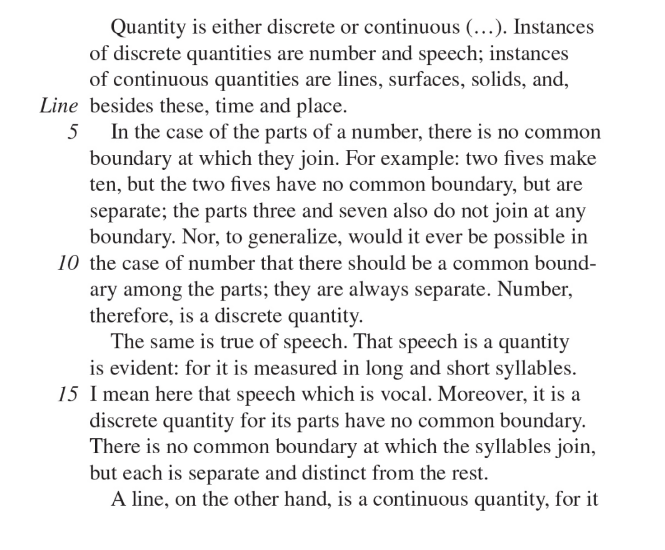

Aristotle liked to classify, and he did so quite often. Some of his classifications have stood the test of time, including the one below, which is the beginning of Part 6 of an essay entitled “Categories.”

Here, Aristotle’s division of quantity into two categories (discrete and continuous) makes sense.

The examples that he uses to illustrate the nature of his categories reveal a great deal about his interests: time, space, language, and mathematics.

This is a well-organized passage; the categories are well-defined and Aristotle clearly explains how the members of each category have been classified.

When and How to Use Classification

When you’re asked to analyze and explain something, classification will be very useful.

Make sure you have a central idea (thesis).

Sort your information into meaningful groups.

Make sure you have a manageable number of categories—three or four.

Make sure the categories (or the elements in the categories) do not overlap.

Before writing, make sure the categories and central idea (thesis) are a good fit.

As you write, do not justify your classification unless this is somehow necessary to address a very bizarre free-response question.

Illustration

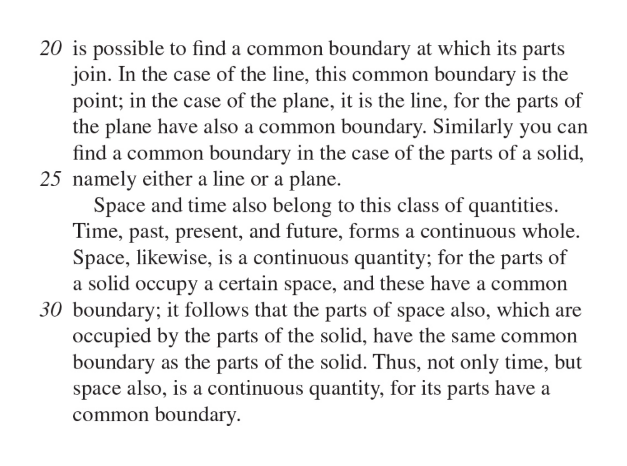

Read the following introduction paragraph from a student essay based on Candide, and as you do so, evaluate the effectiveness of the examples that it uses.

Surely you agree that the examples are not convincing, but you should also understand that they are not even relevant.

Implicit in the examples chosen is the reduction of the best of all possible worlds to the writer’s own tiny corner.

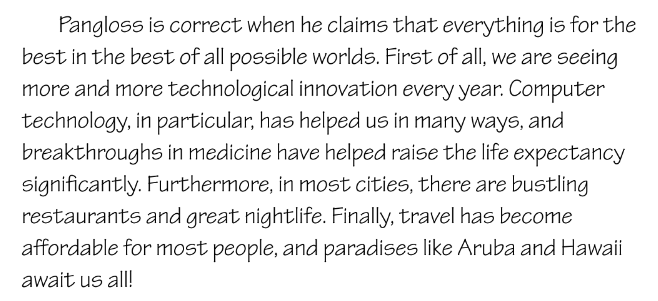

A better approach would be something as follows:

While the second essay may be naive, at least it does its best to substantiate an untenable position.

Without any doubt, the examples in the second passage are much more appropriate for the argument than those that were used in the first passage.

When and How to Use Example (Illustration)

Use examples that your reader (the person who reads your essays) will identify with and understand.

Draw your examples from “real life,” “real” culture (literature, art, classical music, and so on), and well-known folklore.

Make sure the example really does illustrate your point.

Introduce your examples using transitions, such as for example, for instance, case in point, and consider the case of.

A single example that is perfectly representative can serve to illustrate your point.

A series of short, less-perfect (but still relevant) examples can, by their accumulation, serve to illustrate your point.

Remember that you are in control of what you write.

Quality is more important than quantity; poorly chosen examples detract significantly from your presentation.

Analogy

Analogies are sometimes used to explain things that are difficult to understand by comparing them with things that are easier to understand.

You can also use an analogy to explain something that’s abstract by comparing it with something that’s concrete.

The most famous philosophical analogy serves as the basis for Plato’s “allegory of the cave.”

This is only part of the analogy, but you probably get the idea. Socrates uses this analogy to explain that we think that we see things just as they really are in our world, but that we are seeing only reflections of a greater truth, an abstraction that we fail to grasp. The cave is our world; the shadows are the objects and people that we “see.” We are like the prisoners, for we are not free to see what creates the shadows; the truth, made up of ideal forms, is out in the light.

When and How to Use Analogy

Use analogy for expository writing (explanation).

Do not use analogy for argumentative writing (argumentation).

Use analogy to explain something that is abstract or difficult to understand.

Make sure your audience will readily understand your “simple” or concrete subject.

Next Chapter: Chapter 3: Complex Rhetorical Modes

Knowt

Knowt