Chapter 6: Roman Art

Key Notes

- Time Period

- Legendary founding of Rome by Romulus and Remus : 753 B.C.E.

- Roman Republic : 509–27 B.C.E.

- Roman Empire : 27 B.C.E.–410 C.E.

- Culture, beliefs, and physical settings

- Roman art was produced in the Mediterranean basin from 753 B.C.E. to 337 C.E.

- Roman art can be subdivided into the following periods: Republican, Early Imperial, Late Imperial, and Late Antique.

- Roman culture is rich in written literature: i.e., epics, poetry, dramas.

- Art Making

- Roman art reflects influences from other ancient traditions.

- Roman architecture reflects ancient traditions as well as technological innovations.

- Cultural Interactions

- There is an active exchange of artistic ideas throughout the Mediterranean.

- Roman works were influenced by Greek objects. In fact, many Hellenistic works survive as Roman copies.

- Audience, functions and patron

- Ancient Roman art is influenced by civic responsibility and the polytheism of its religion.

- Roman art first shows republican and then imperial values.

- Roman architecture shows a preference for large public monuments..

- Theories and Interpretations

- The study of art history is shaped by changing analyses based on scholarship, theories, context, and written records.

- Roman art has had an important impact on European art, particularly since the eighteenth century.

- Roman writing contains some of the earliest contemporary accounts about art and artists.

Historical Background

- From hillside village to world power, Rome rose to glory by diplomacy and military might.

- The effects of Roman civilization are still felt today in the fields of law, language, literature, and the fine arts.

- According to legend, Romulus and Remus, abandoned twins, were suckled by a she-wolf, and later established the city of Rome on its fabled seven hills.

- At first the state was ruled by kings, who were later overthrown and replaced by a Senate.

- The Romans then established a democracy of a sort, with magistrates ruling the country in concert with the Senate, an elected body of privileged Roman men.

- Variously well-executed wars increased Rome’s fortunes and boundaries.

- In 211 B.C.E., the Greek colony of Syracuse in Sicily was annexed.

- This was followed, in 146 B.C.E., by the absorption of Greece.

- The Romans valued Greek cultural riches and imported boatloads of sculpture, pottery, and jewelry to adorn the capital.

- A general movement took hold to reproduce Greek art by establishing workshops that did little more than make copies of Greek sculpture.

- Civil war in the late Republic caused a power vacuum that was filled by Octavian, later called Augustus Caesar, who became emperor in 27 B.C.E.

- From that time, Rome was ruled by a series of emperors as it expanded to faraway Mesopotamia and then retracted to a shadow of itself when it was sacked in 410 C.E.

- The single most important archaeological site in the Roman world is the city of Pompeii, which was buried by volcanic ash from Mount Vesuvius in 79 C.E.

- In 1748, systematic excavation—actually more like fortune hunting—was begun.

- Because of Pompeii, we know more about daily life in Rome than we know about any other ancient civilization.

Roman Architecture

- Ashlar Masonry: A technique used where building are built without mortar.

- Carefully cut and grooved stones that support a building without the use of concrete or other kinds of masonry.

- Roman architects understood that arches could be extended in space and form a continuous tunnel-like construction called a barrel vault.

- Groin Vault: A larger more open space, formed when two barrel vaults intersect.

- The latter is particularly important because the groin vault could be supported with only four corner piers, rather than requiring a continuous wall space that a barrel vault needed.

- Pier: a vertical support that holds up an arch or a vault

- Spandrels: The spaces between the arches on the piers.

- Arches and vaults make enormous buildings possible, like the Colosseum (72–80 C.E.), and they also make feasible vast interior spaces like the Pantheon (118–125 C.E.). Concrete walls are very heavy.

- To prevent the weight of a dome from cracking the walls beneath it, coffers are carved into ceilings to lighten the load.

- Coffer: in architecture, a sunken panel in a ceiling

- The Romans used concrete in constructing many of their oversized buildings.

- Much is known about Roman domestic architecture, principally because of what has been excavated at Pompeii.

- The exteriors of Roman houses have few windows, keeping the world at bay.

- A single entrance is usually flanked by stores which face the street.

- Stepping through the doorway one enters an open-air courtyard called an atrium, which has an impluvium to capture rainwater.

- Impluvium: a rectangular basin in a Roman house that is placed in the open-air atrium in order to collect rainwater

- Private bedrooms, called cubicula, radiate around the atrium.

- Cubiculum: a Roman bedroom flanking an atrium; in Early Christian art, a mortuary chapel in a catacomb

- The atrium provides the only light and air to these windowless, but beautifully decorated, rooms.

- Atrium (plural: atria): a courtyard in a Roman house or before a Christian church

- The Romans placed their intimate rooms deeper into the house. Eventually another atrium, perhaps held up by columns called a peristyle, provided access to a garden flanked by more cubicula.

- The center of the Roman business world was the forum, a large public square framed by the principal civic buildings.

- Composite columns first seen in the Arch of Titus have a mix of Ionic (the volute) and Corinthian (the leaf) motifs in the capitals.

- Composite column: one that contains a combination of volutes from the Ionic order and acanthus leaves from the Corinthian order

- Tuscan columns as seen on the Colosseum are unfluted with severe Doric-style capitals

- Keystone: the center stone of an arch that holds the others in place

➼ House of Vettii

Details

- From Imperial Roman,

- 2nd century B.C.E.–1st century C.E.

- Rebuilt c. 67–79 C.E.

- Made of cut stone and fresco

- Found in Pompeii, Italy

Form

- Narrow entrance to the home sandwiched between several shops.

- Large reception area called the atrium, which is open to the sky and has a catch basin called an impluvium in the center; rooms called cubicula radiate around the atrium.

- Peristyle garden in rear with fountain, statuary, and more cubicula; this is the private area of the house.

- Axial symmetry of house; someone entering the house can see through to the peristyle garden in the rear.

- Exterior of house lacks windows; interior lighting comes from the atrium and the peristyle.

Function

- Private citizen’s home in Pompeii

- Originally built during the Republic with early imperial additions.

Context

- Two brothers owned the house; both were freedmen who made their money as merchants.

- Extravagant home symbolized the owners’ wealth.

- After the earthquake of 62 A.D., many wealthy Romans left Pompeii, leading to the rise of the “nouveau riche.”

Image

➼ The Colosseum (Flavian Amphitheater)

Details

- Imperial Roman

- 72–80 C.E.

- Made of stone and concrete

- Found in Rome

Function

- Stadium meant for wild and dangerous spectacles—gladiator combat, animal hunts, naval battles—but not, as tradition suggests, religious persecution.

Form

- Accommodated 50,000 spectators.

- Concrete core, brick casing, travertine facing.

- 76 entrances and exits circle the façade.

- Interplay of barrel vaults, groin vaults, arches.

- Façade has engaged columns

- first story is Tuscan,

- second story is Ionic,

- third story is Corinthian, and

- the top story is flattened Corinthian; each thought of as lighter than the order below.

- Flagstaffs: These staffs are the anchors for a retractable canvas roof, called a velarium.

- Velarium: A retractable canvas roof used to protect the crowd on hot days.

- Sand was placed on the floor to absorb the blood; occasionally the sand was dyed red.

- Hypogeum: The subterranean part of an ancient building.

Context

- Real name is the Flavian Amphitheater; the name Colosseum comes from a colossal statue of Nero that used to be adjacent.

- The building illustrates what popular entertainment was like for ancient Romans.

- Entrances and staircases were separated by marble and iron railings to keep the social classes separate; women and the lower classes sat at the top level.

- Much of the marble was pulled off in the Middle Ages and repurposed.

Images

Content Area for Petra: West and Central Asia

➼ Treasury and Great Temple of Petra, Jordan

Details

- Nabataean Ptolemaic and Roman

- c. 400 B.C.E.–100 C.E.

- Made of cut rock

- Found in Jordan

Context

- Petra was a central city of the Nabataeans, a nomadic people, until Roman occupation in 106 C.E.

- The city was built along a caravan route.

- They buried their dead in the tombs cut out of the sandstone cliffs.

- Five hundred royal tombs in the rock, but no human remains found; burial practices are unknown; tombs are small.

- The city is half built, half carved out of rock. –The city is protected by a narrow canyon entrance.

- The Roman emperor Hadrian visited the site and named it after himself: Hadriane Petra.

Content

- Approached through a monumental gateway, called a propylaeum, and a grand staircase that leads to a colonnade terrace in the lower precincts.

- A second staircase leads to the upper precincts.

- A third staircase leads to the main temple.

Form

- Nabataean concept and Roman features such as Corinthian columns.

- Monuments carved in traditional Nabataean rock-cut cliff walls.

- Lower story influenced by Greek and Roman temples but with unusual features:

- Columns not proportionally spaced.

- Pediment does not cover all columns, only the central four.

- Upper floor: broken pediment with a central tholos.

- Combination of Roman and indigenous traditions.

- Greek, Egyptian, and Assyrian gods on the façade.

- Interior: one central chamber with two flanking smaller rooms.

Function: In reality, it was a tomb, not a “treasury,” as the name implies.

Images

➼ Forum of Trajan

Details

- By Apollodorus of Damascus

- 106–112 C.E.

- Made of brick and concrete

- Found in Rome, Italy

Form

- Large central plaza flanked by stoa-like buildings on each side.

- Originally held an equestrian monument dedicated to Trajan in the center.

Function: Part of a complex that included the Basilica of Ulpia, Trajan’s markets, and the Column of Trajan.

Context: Built with booty collected from Trajan’s victory over the Dacians.

Image

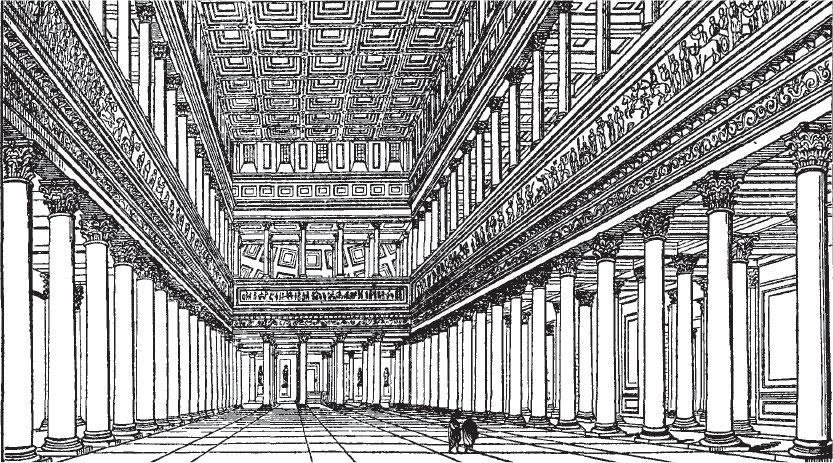

➼ Basilica of Ulpia

Details

- c. 112 C.E.

- Made of brick and concrete

- Found in Rome, Italy

- Basilica: in Roman architecture, a large axially planned building with a nave, side aisles, and apses

Form

- Grand interior space (385 feet by 182 feet) with two apses.

- Nave is spacious and wide.

- Double colonnaded side aisles.

- Second floor had galleries or perhaps clerestory windows.

- Timber roof 80 feet across.

- Basilican structure can be traced back to Greek stoas.

Functional: Law courts held here; apses were a setting for judges.

Context

- Said to have been paid for by Trajan’s spoils taken from the defeat of the Dacians.

- Ulpius was Trajan’s family name.

Image

➼ Trajan Markets

Details

- 106–112 C.E.

- Made of brick and concrete

- Found in Rome, Italy

Form

- Semicircular building held several levels of shops.

- Main space is groin vaulted; barrel vaulted area with the shops.

Function

- Multilevel mall.

- Original market had 150 shops.

Materials: Use of exposed brick indicates a more accepted view of this material, which formerly was thought of as being unsuited to grand public buildings.

Image

➼ Pantheon

Details

- Imperial Roman

- 118–125 C.E.

- Made of concrete with stone facing

- Found Rome, Italy

Form Exterior

- Corinthian-capital porch in front of this building.

- Façade has two pediments, one deeply recessed behind the other; it is difficult to see the second pediment from the street.

Form Interior

- Interior contains a slightly convex floor for water drainage.

- Square panels on floor and in coffers contrast with roundness of walls; circles and squares are a unifying theme.

- Coffers may have been filled with rosette designs to simulate stars.

- Cupola walls are enormously thick: 20 feet at base.

- Cupola: a small dome rising over the roof of a building; in architecture, a cupola is achieved by rotating an arch on its axis

- Thickness of walls is thinned at the top; coffers take some weight pressure off the walls.

- Oculus, 27 feet across, allows for air and sunlight; sun moves across the interior much like a spotlight.

- Oculus: a circular window in a church, or a round opening at the top of a dome

- Height of the building equals its width; the building is based on the circle; a hemisphere.

- Walls have seven niches for statues of the gods.

- Triumph of concrete construction.

- Was originally brilliantly decorated.

Function

- Traditional interpretation: it was built as a Roman temple dedicated to all the gods.

- Recent interpretation: it may have been dedicated to a select group of gods and the divine Julius Caesar and/or used for court rituals.

- It is now a Catholic church called Santa Maria Rotonda.

Context

- Inscription on the façade: “Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, having been consul three times, built it.”

- The name Pantheon is from the Greek meaning “all the gods” or “common to all the gods.”

- Originally had a large atrium before it; originally built on a high podium; modern Rome has risen up to that level.

- Interior symbolized the vault of the heavens.

Images

Roman Painting

- Interior wall paintings, created to liven up generally windowless Roman cubicula, were frescoed with mythological scenes, landscapes, and city plazas.

- Fresco: a painting technique that involves applying water-based paint onto a freshly plastered wall. The paint forms a bond with the plaster that is durable and long-lasting

- Mosaics were favorite floor decorations—stone kept feet cool in summer.

- Encaustics from Egypt provided lively individual portraits of the deceased.

- Encaustic: an ancient method of painting that uses colored waxes burned into a wooden surface

- Murals were painted with some knowledge of linear perspective—spatial relationships in landscape paintings appeared somewhat consistent.

- Perspective: depth and recession in a painting or a relief sculpture.

- Orthogonals recede to multiple vanishing points in the distance.

- Sometimes, to present an object in the far distance, an artist used atmospheric perspective, a technique that employs cool pastel colors to create the illusion of deep recession.

- Figures were painted in foreshortening, where they are seen at an oblique angle and seem to recede into space.

- Foreshortening: a visual effect in which an object is shortened and turned deeper into the picture plane to give the effect of receding in space

- So much Pompeian wall painting survives that an early history of Roman painting can be reconstructed.

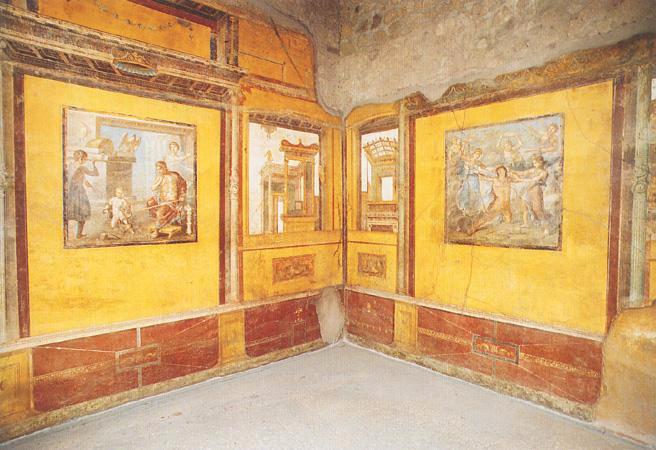

- First Pompeian Style: Characterized by painted rectangular squares meant to resemble marble facing.

- Second Pompeian Style: had large mythological scenes and/or landscapes dominating the wall surface. Painted stucco decoration of the First Style appears beneath in horizontal bands.

- Third Pompeian Style: characterized by small scenes set in a field of color and framed by delicate columns of tracery.

- Fourth Pompeian Style combines elements from the previous three:

- The painted marble of the First Style is at the base;

- the large scenes of the Second Style and

- the delicate small scenes of the Third Style are intricately interwoven.

- The frescos from the Pentheus Room are from the Fourth Style.

➼ Pentheus Room

Details

- Imperial Roman

- 62–79 C.E.

- fresco

- Foun in Pompeii, Italy

Function

- Triclinium: a dining room in a Roman house.

Context

- Main scene is the death of the Greek hero Pentheus.

- Pentheus opposed the cult of Bacchus and was torn to pieces by women, including his mother, in a Bacchic frenzy; two women are pulling at his hair in this image.

- Punishment of Pentheus is eroticized; central figure with arms outstretched; exposed nakedness of his body.

- Architecture is seen through painted windows; imaginary landscape.

- This painting opens the room with the illusion of windows and a sunny cityscape beyond.

Image

Roman Sculpture

- The instructional program included painted relief and freestanding sculptures. Later arches utilized current art with statues from two-hundred-year-old emperors.

- The Column of Trajan (112 C.E.), had an entrance at the base, from which the visitor could ascend a spiral staircase and emerge onto a porch, where Trajan’s architectural accomplishments would be revealed in all their glory.

- A statue of the emperor, which no longer exists, crowned the ensemble.

- The banded reliefs tell the story of Trajan’s conquest of the Dacians.

- The spiraling turn of the narratives made the story difficult to read; scholars have suggested a number of theories that would have made this column, and works like it, legible to the viewer.

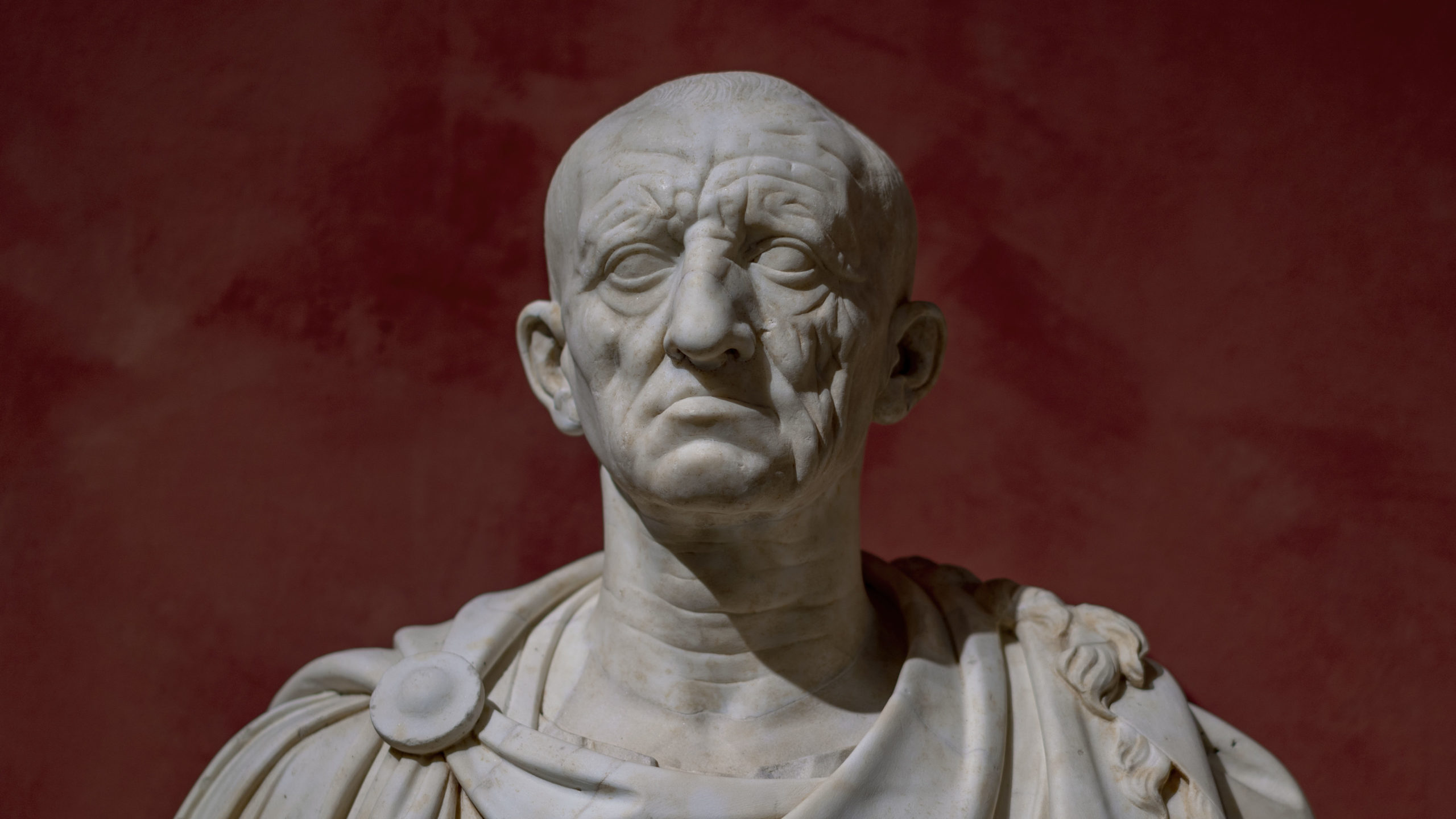

- Republican Sculpture

- Republican busts of noblemen, called veristic sculptures, are strikingly and unflatteringly realistic, with the age of the sitter seemingly enhanced.

- Veristic: sculptures from the Roman Republic characterized by extreme realism of facial features

- Bust: a sculpture depicting the head, neck, and upper chest of a figure

- Republican full-length statues concentrate on the heads, some of which are removed from one work and placed on another.

- The bodies were occasionally classically idealized, symbolizing valor and strength.

- Imperial Sculpture

- Emperors, who were divine, were shown differently than senators. The contrapposto, perfect proportions, and heroic attitudes of Greek statues inspired

- Contrapposto: a graceful arrangement of the body based on tilted shoulders and hips and bent knees

- Roman artists. Forms become less individualistic, iconography more heavenly.

- At the end of the Early Imperial period, a stylistic shift begins to take place that transitions into the Late Imperial style.

- Compositions are marked by figures that lack individuality and are crowded tightly together.

- Everything is pushed forward on the picture plane, as depth and recession were rejected along with the classicism they symbolize.

- Proportions are truncated—contrapposto ignored; bodies are almost lifeless behind masking drapery.

- Emperors are increasingly represented as military figures rather than civilian rulers.

➼ Head of a Roman Patrician

Details

- Republican Roman

- c. 75–50 B.C.E.

- Made of marble

- Found in Museo Torlonia, Rome

Function

- Funerary context; funerary altars adorned with portraits, busts, or reliefs and cinerary urns.

- Tradition of wax portrait masks in funeral processions of the upper class to commemorate their history.

- Portraits housed in family shrines honoring deceased relatives.

Context

- Realism of the portrayal shows the influence of Greek Hellenistic art and late Etruscan art.

- Bulldog-like tenacity of features; overhanging flesh; deep crevices in face.

- Full of experience and wisdom—traits Roman patricians would have desired.

- Features may have been exaggerated by the artist to enhance adherence to Roman Republican virtues such as stoicism, determination, and foresight.

- Busts are mostly of men, often depicted as elderly.

Image

➼ Augustus of Prima Porta

Details

- Imperial Roman

- Early 1st century C.E.

- Made of marble

- Found in Vatican Museums, Rome

Form

- Contrapposto.

- References Polykleitos’s Doryphoros.

- Characteristic of works depicting Augustus is the part in the hair over the left eye and two locks over the right.

- Heroic, grand, authoritative ruler; over life-size scale.

- Back not carved; figure meant to be placed against a wall.

- Oratorical pose.

Function and Original Context

- Found in the villa of Livia, Augustus’s wife; may have been sculpted to honor him in his lifetime or after his death (Augustus is barefoot like a god, not wearing military boots).

- May have been commissioned by Emperor Tiberius, Livia’s son, whose diplomacy helped secure the return of the eagles; thus it would serve as a commemoration of Augustus and the reign of Tiberius.

Content

- Idealized view of the Roman emperor, not an individualized portrait.

- Confusion between God and man is intentional; in contrast with Roman Republican portraits.

- Standing barefoot indicates he is on sacred ground.

- On his breastplate are a number of gods participating in the return of Roman standards from the Parthians; Pax Romana.

- Breastplate indicates he is a warrior; judges’ robes show him as a civic ruler.

- He may have carried a sword, pointing down, in his left hand.

- His right hand is in a Roman orator pose; perhaps it held laurel branches.

- At base: Cupid on the back of a dolphin—a reference to Augustus’s divine descent from Venus; perhaps also a symbol of Augustus’s naval victory over Mark Antony and Cleopatra.

- Maybe a copy of a bronze original, which probably did not have the image of Cupid.

Image

➼ Column of Trajan

Details

- 113 C.E.

- Made of marble

- Found in Rome

Form

- A 625-foot narrative cycle (128 feet high) wrapped around the column tells the story of Trajan’s defeat of the Dacians; this is the earliest example of this kind of structure.

- Crowded composition.

- Base of the column has an oak wreath, the symbol of victory.

- Low relief; few shadows to cloud what must have been a very difficult object to view in its entirety.

Function

- Visitors who entered the column were meant to wander up the interior spiral staircase to the viewing platform at the top where a heroic nude statue of the emperor was placed.

- Base contains the burial chamber of Trajan and his wife, Plotina, whose ashes were placed in golden urns in the pedestal.

Technique: Roman invention of a tall hollowed out column with an interior spiral staircase.

Content

- 150 episodes, 2,662 figures, 23 registers—continuous narrative.

- Continuous narrative: a work of art that contains several scenes of the same story painted or sculpted in continuous succession

- Scenes on the column depict the preparation for battle, key moments in the Dacian campaign, and many scenes of everyday life

- Trajan appears 58 times in various roles: commander, statesman, ruler, etc.

Context

- Stood in Trajan’s Forum at the far end surrounded by buildings.

- Scholarly debate over the way it was meant to be viewed.

- A viewer would be impressed with Trajan’s accomplishments, including his forum and his markets.

- Two Roman libraries containing Greek and Roman manuscripts flanked the column.

Image

➼ Ludovisi Battle Sarcophagus

Details

- Late Imperial Roman

- c. 250 C.E.

- Made of marble

- Found in National Roman Museum, Rome

Form

- Extremely crowded surface with figures piled atop one another; horror vacui.

- Abandonment of classical tradition in favor of a more animated and crowded space.

- Horror vacui: (Latin for a “fear of empty spaces”) a type of artwork in which the entire surface is filled with objects, people, designs, and ornaments in a crowded, sometimes congested way

- Figures lack individuality.

Function: Interment of the dead; rich carving suggests a wealthy patron with a military background.

Technique

- Very deep relief with layers of figures.

- Complexity of composition with deeply carved undercutting.

Content

- Roman army trounces bearded and defeated barbarians.

- Romans appear noble and heroic while the Goths are ugly.

- Romans battling “barbaric” Goths in the Late Imperial period.

- Youthful Roman general appears center top with no weapons, the only Roman with no helmet, indicating that he is invincible and needs no protection; he controls a wild horse with a simple gesture.

Context

- Confusion of battle is suggested by congested composition.

- Rome at war throughout the third century.

- So called because in the seventeenth century it was in Cardinal Ludovisi’s collection in Rome.

Image