Chapter 15: Early Renaissance in Italy: Fifteenth Century

Key Notes

Time Period: 1400–1500

Takes place in the courts of Italian city-states: Ferrara, Florence, Mantua, Naples, Rome, Venice, and so on.

Culture, beliefs, and physical settings

Renaissance art is generally the art of Western Europe.

Renaissance art is influenced by the art of the classical world, Christianity, a greater respect for naturalism, and formal artistic training.

Cultural interactions

There are the beginnings of global commercial and artistic networks.

Materials and Processes

The period is dominated by an experimentation of visual elements, i.e., atmospheric perspective, a bold use of color, creative compositions, and an illusion of naturalism

Audience, functions, and patron

There is a more pronounced identity of the artist in society; the artist has more structured training opportunities.

Theories and Interpretations

Renaissance art is studied in chronological order.

There is a large body of primary source material housed in libraries and public institutions.

Historical Background

Italian city-states were controlled by ruling families who dominated politics

These princes were lavish spenders on the arts, and great connoisseurs of cutting-edge movements in painting and sculpture.

They embellished their palaces with the latest innovative paintings by artists such as Lippi and Botticelli.

They commissioned architectural works from the most pioneering architects of the day.

Princely courts eventually shifted from religious to secular concerns in a humanistic spirit.

Humanism: an intellectual movement in the Renaissance that emphasized the secular alongside the religious.

Humanists were greatly attracted to the achievements of the classical past, and stressed the study of classical literature, history, philosophy, and art

Patronage and Artistic Life

The patrons of this time dictated the quantity of gold used on altarpieces and which family members were to be shown in paintings.

Great families often had their own chapel in the local church.

These churches' mysticism was enhanced by muralists.

Quattrocento: the 1400s, or fifteenth century, in Italian art

Early Renaissance Architecture

Renaissance architecture requires order, clarity, and light.

Gothic churches' gloom, mystery, and sacredness were barbarous.

Wide windows, minimal stained glass, and vibrant wall murals replaced it.

Renaissance architecture emphasizes geometric designs, yet all buildings require mathematics to support their technical principles.

Vitruvius' ideal proportions created harmony.

Humanistic values were reflected in Florentine Renaissance church interior ratios and proportions.

Unvaulted naves with coffered ceilings reminded Early Christianity.

Thus, the crossing is twice the nave bays, the nave twice the side aisles, and the side aisles twice the side chapels.

The nave is two-thirds arches and columns.

As in Brunelleschi's Pazzi Chapel, the nave's white and gray marble floor patterns emphasize this logic.

Alberti's Palazzo Rucellai and other Florentine buildings feature austere, three-story façades.

The first level is usually for public use and business.

A sturdy string course marks the ceiling and floor of the second storey, which rises light.

Roman temple-style cornices top the third story.

Mullion: a central post or column that is a support element in a window or a door

Orthogonal: lines that appear to recede toward a vanishing point in a painting with linear perspective

➼ Pazzi Chapel

Details

Designed by Filippo Brunelleschi

Basilica di Santa Croce

Designed 1423; Built 1429–1461,

A masonry,

Found in Florence, Italy

Form

Two barrel vaults on the interior; small dome over crossing; pendentives support dome; oculus in the center.

Interior has a quiet sense of color with muted tones that is punctuated by glazed terra cotta tiles.

Use of pietra serena (a grayish stone) in contrast to whitewashed walls accentuates basic design structure.

Pietra serena: a dark-gray stone used for columns, arches, and trim details in Renaissance buildings

Inspired by Roman triumphal arches.

Ideal geometry in the plan of the building.

Function

Chapter house: a meeting place for Franciscan monks; bench that wraps around the interior provides seating for meetings.

Rectangular chapel with an apse and an altar attached to the church of Santa Croce, Florence.

Attribution

Attribution of portico by Brunelleschi has been recently questioned;

The building may have been designed by Bernardo Rossellino or his workshop.

Patronage

Patrons were the wealthy Pazzi family, who were rivals of the Medici.

The family coat-of-arms, two outward facing dolphins, is placed at the base of each pendentive on the interior.

Image

➼ Palazzo Rucellai

Details

Designed by Leon Battista Alberti

c. 1450, stone,

A masonry

Found in Florence, Italy

Form

Three horizontal floors separated by a strongly articulated stringcourse; each floor is shorter than the one below.

Pilasters rise vertically and divide the spaces into squarish shapes.

An emphasized cornice caps the building.

Square windows on the first floor; windows with mullions on the second and third floors.

Rejects rustication of earlier Renaissance palaces; used beveled masonry joints instead.

Benches on lower level connect the palazzo with the city.

Function

City residence of the Rucellai family.

The building format expresses classical humanist ideals for a residence:

the bottom floor was used for business;

the family received guests on the second floor;

the family’s private quarters were on the third floor;

the hidden fourth floor was for servants.

Context

The articulation of the three stories links the building to the Colosseum levels, which have arches framed by columns:

the first floor pilasters are Tuscan (derived from Doric);

the second are Alberti’s own invention (derived from Ionic);

the third are Corinthian.

Original building:

Five bays on the left, with a central door.

Second doorway bay and right bay added later.

Eighth bay fragmentary: owners of house next door refused to sell, and the Palazzo Rucellai never expanded.

Patronage

Patron was Giovanni Rucellai, a wealthy merchant.

Rucellai coat-of-arms, a rampant lion, is placed over two second-floor windows.

Friezes contain Rucellai family symbols: billowing sails.

Image

Fifteenth Century Italian Painting and Sculpture

Linear perspective, which some experts believe the Romans used, is the most distinctive feature of Italian Renaissance art.

In the early fifteenth century, Filippo Brunelleschi created perspective while sketching the Florence Cathedral Baptistery.

Some painters were obsessed with perspective, presenting things and people in proportion, unlike medieval painting, which emphasized humans.

Linear perspective was quickly adopted by pre-Traditional artists.

The artists used trompe l'oeil to purposely deceive the viewer.

Trompe l’oeil: (French, meaning “fools the eye”) a form of painting that attempts to represent an object as existing in three dimensions, and therefore resembles the real thing.

By the end of the fifteenth century, portraits and mythical subjects had replaced religious paintings, expressing humanist ideas.

Humanism and Greco-Roman classics revive interest in genuine Greek and Roman sculptures.

Medieval painters saw old naked glory as heathen.

Donatello's David begins the century-long renaissance of nudity in life-size sculpture in Florence.

Increased anatomy study leads to nudity.

Nude sketches of heroes are cast in stone and metal.

Some painters display tremendous physical interplay of shapes in their twisting motions and straining muscles.

Bottega: the studio of an Italian artist

Perspective: depth and recession in a painting or a relief sculpture.

Objects shown in linear perspective achieve a three-dimensionality in the two-dimensional world of the picture plane.

Lines, called orthogonals, draw the viewer back in space to a common point, called the vanishing point.

Paintings, however, may have more than one vanishing point, with the orthogonals leading the eye to several parts of the work.

Landscapes that give the illusion of distance are in an atmospheric or aerial perspective.

➼ Madonna and Child with Two Angels

Details

Painted by Fra Filippo Lippi

c. 1465

Tempera on wood

Found in Uffizi, Florence

Madonna: the Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus Christ

Content and Symbolism

Symbolic landscape

Rock formations symbolize the Christian Church.

City near Madonna's head is the Heavenly Jerusalem.

Pearl motif: seen in headdress and pillow as products of the sea.

Pearls used as symbols in scenes of the Incarnation of Christ.

Context

Mary is seen as a young mother.

Model may have been the artist’s lover.

Landscape inspired by Flemish painting.

Scene depicted as if in a window in a Florentine home.

Humanization of a sacred theme; there is a sense of domestic intimacy.

Lippi was a monk, as indicated by the word “Fra” that precedes his name; he was working in a Carmelite monastery under the patronage of the Medici.

Image

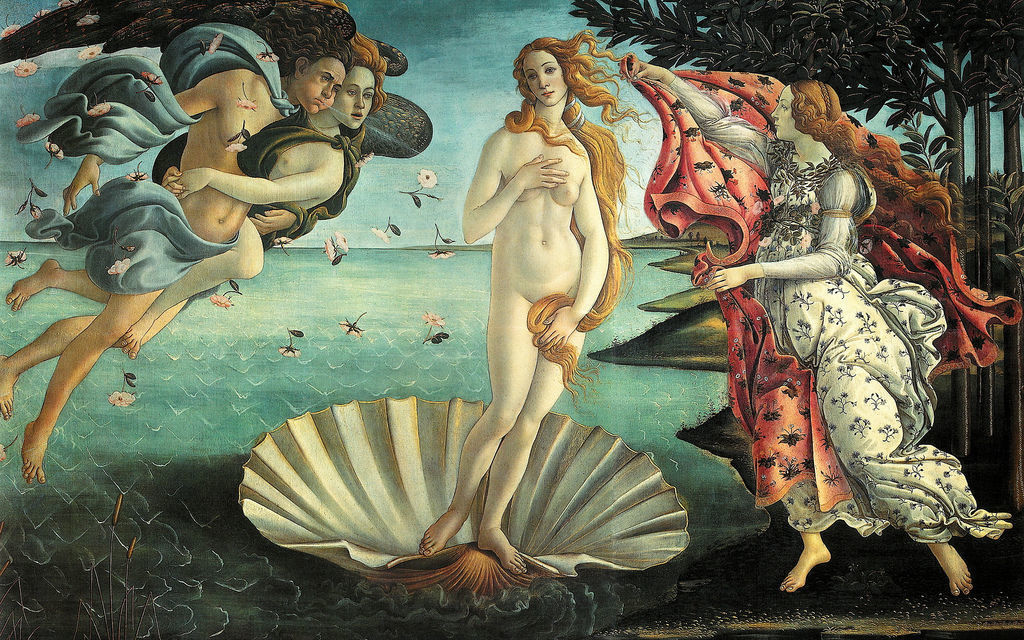

➼ Birth of Venus

Details

Painted by Sandro Botticelli

c. 1484–1486

Tempera on canvas

Found in Uffizi, Florence

Form

Crisply drawn figures.

Landscape flat and unrealistic; simple V-shaped waves.

Figures float, not anchored to the ground.

Content

Venus emerges fully grown from the foam of the sea with a faraway look in her eyes.

Roses scattered before her; roses created at the same time as Venus, symbolizing that love can be painful.

On the left: Zephyr (west wind) and Chloris (nymph).

On the right: handmaiden rushes to clothe Venus.

Context

Medici commission; may have been commissioned for a wedding celebration.

Painting based on a popular court poem by the writer Poliziano, which itself is based on Homeric hymns and Hesiod’s Theogony.

A revival of interest in Greek and Roman themes can be seen in this work.

Earliest full-scale nude of Venus in the Renaissance.

Reflects emerging Neoplatonic thought.

Neoplatonism: a school of ancient Greek philosophy that was revived by Italian humanists of the Renaissance

Image

➼ David

Details

Sculpted by Donatello

c. 1440–1460

Made of bronze

Found in National Museum, Bargello, Florence

Form

First large bronze nude since antiquity.

Exaggerated contrapposto of the body.

Sleekness of the black bronze adds to the femininity of the work.

Androgynous figure; homoerotic overtones.

Function

Life-size work, probably meant to be housed in the Medici palace courtyard; not for public viewing.

Content

The work depicts the moment after David slays the Philistine Goliath with a rock from a slingshot; David then decapitates Goliath with his own sword.

David contemplates his victory over Goliath, whose head is at his feet; David’s head is lowered to suggest humility.

Laurel on David’s hat indicates he was a poet; the hat is a foppish Renaissance design.

Context

David symbolizes Florence taking on larger forces with ease; perhaps Goliath would have been equated with the Duke of Milan.

Nothing is known of its commission or patron, but it was placed in the courtyard of the Medici palace in Florence.

Modern theory alleges that this is a figure of Mercury, and that the decapitated head is of Argo;

Mercury is the patron of the arts and merchants, and therefore an appropriate symbol for the Medici.

Image

Knowt

Knowt