Alliances

Alliances as a cause of World War I

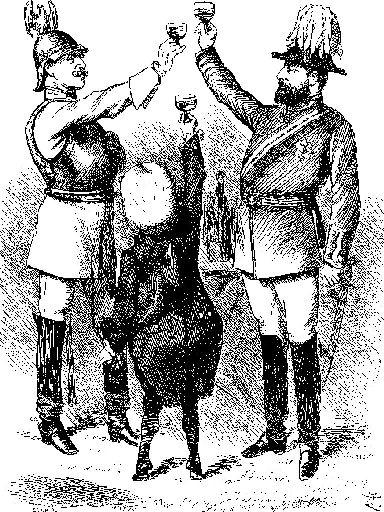

A representation of the Triple Alliance, with Italy as the junior partner

Alliances are perhaps the best known cause of World War I. During the 19th century, European nations signed a series of agreements that shuffled them, broadly speaking, into two large and opposing blocs. It followed that conflict between any nations from these blocs might throw the entire continent into war. But to what extent did the alliance system make war in Europe inevitable?

What is an alliance?

An alliance is a formal political, military or economic agreement between two or more nations. Alliances are a common feature of human civilisation. They are not a new phenomenon and predate the rise of modern nation-states – there are examples of alliances between tribes, city-states and kingdoms dating back many centuries.

In modern history, alliances have often contained commitments that in the event of war or aggression, one member nation will support the others. The terms and the extent of this support is outlined in the alliance document, and can range from financial or logistic backing, like the supply of materials or weapons, to military mobilisation and a declaration of war. Alliances may also contain economic elements, such as trade agreements, investment or loans.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries European nations formed, annulled and restructured alliances on a regular basis. By 1914, the Great Powers of Europe had aligned and shuffled themselves into two allied blocs. The existence of these two blocs, effectively in opposition to each other, meant that war between two nations could lead to war between them all.

Europe’s alliance system

As mentioned, alliances were for from new in European history. For centuries, Europe had been a melting pot of ethnic and territorial rivalries, political intrigues and paranoia. France and England were ancient antagonists whose rivalry erupted into open warfare several times between the 14th and early 19th centuries. Relations between the French and Germans were also troubled, while France and Russia also had their differences.

Alliances came to provide European states with a measure of protection. They served as a deterrent to larger states who might make war on smaller ones.

During the 1700s, alliances were used both as a defensive measure and a political device. Kings and princes regularly formed or re-formed alliances, usually to advance their own interests or isolate rivals. Many of these alliances and alliance blocs were short lived. Some collapsed when new leaders emerged; others were nullified or replaced by new alliances.

The Napoleonic Wars

The rise of French dictator Napoleon Bonaparte in the early 1800s ushered in a brief period of ‘super alliances’. European nations allied themselves either in support of Bonaparte or to defeat him. Between 1797 and 1815, European leaders formed seven anti-Napoleonic coalitions. At various times, these coalitions included Britain, Russia, Holland, Austria, Prussia, Sweden, Spain and Portugal.

After Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815, European leaders worked to restore normality and stability to the continent. The Congress of Vienna (1815) established an informal system of diplomacy, defined national boundaries and sought to prevent wars and revolutions. It was hoped this would secure decades of relative peace and prosperity.

This congress system worked for a time but started to weaken in the mid 1800s. Imperial interests, changes in government, a series of revolutions (1848) and rising nationalist movements in Germany, Italy and elsewhere saw European rivalries and tensions increase again. Nations again turned to alliances to defend and advance their interests. Some of the individual agreements signed in the mid to late 1800s are summarised below.

19th and early 20th century alliances

The Treaty of London (1839). Though not strictly an alliance, this multi-lateral treaty acknowledged the existence of Belgium as an independent and neutral state. Several of Europe’s great powers, including Great Britain and Prussia, were signatories to this treaty. Belgium had earned statehood in the 1830s after separating from southern Holland. The Treaty of London was still in effect in 1914, so when German troops invaded Belgium in August 1914, the British considered it a violation of the treaty.

The Three Emperors’ League (1873). This league was a three way alliance between the ruling monarchs of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Russia. The Three Emperors’ League was engineered and dominated by the Prussian statesman Otto von Bismarck, who saw it as a means of securing the balance of power in Europe. Disorder in the Balkans undermined Russia’s commitment to the league, which collapsed in 1878. The Three Emperors’ League, without Russia, formed the basis of the Triple Alliance.

The Dual Alliance (1879). This was a binding military alliance between Germany and Austria-Hungary, that required each signatory to support the other if one was attacked by Russia. It was signed after the collapse of the Three Emperors’ League and during a period of Austro-Russian tension in the Balkans. The alliance was welcomed by nationalists in Germany, who believed that German-speaking Austria should be absorbed into greater Germany.

The Triple Alliance (1882). This complex three way alliance between Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy was driven by anti-French and anti-Russian sentiment. Each of the three signatories was committed to provide military support to the others, if one was attacked by two other powers – or if Germany and Italy were attacked by France. Italy, being newly formed and militarily weak, was viewed as a minor partner in this alliance.

The Franco-Russian Alliance (1894). This military alliance between France and Russia restored cordial relations between the two imperial powers. The Franco-Russian Alliance was in effect a response to the Triple Alliance, which had isolated France. The signing of the Franco-Russian Alliance was an unexpected development that thwarted German plans for mainland Europe and angered Berlin. It also provided economic benefits to both signatory nations, allowing Russia access to French loans and providing French capitalists with access to Russian mining, industry and raw materials.

The Entente Cordiale (1904). Meaning ‘friendly agreement’, the Entente Cordiale was a series of agreements between Britain and France. The Entente ended a century of hostility between the two cross-channel neighbours. It also resolved some colonial disagreements and other minor but lingering disputes. The Entente was not a military alliance; neither signatory was obliged to provide military support for the other. Nevertheless it was seen as the first step towards an Anglo-French military alliance.

The Anglo-Russian Entente (1907). This agreement between Britain and Russia eased tensions and restored good relations between the two nations. Britain and Russia had spent much of the 19th century as antagonists, going to war in the Crimea (1853-56) and later reaching the verge of war twice. The Anglo-Russian Entente resolved several points of disagreement, including the status of colonial possessions in the Middle East and Asia. It did not involve any military commitment or support.

The Triple Entente (1907). This treaty consolidated the Entente Cordiale and the Anglo-Russian Entente into a three way agreement between Britain, France and Russia. Again, it was not a military alliance – however the three Ententes of 1904-7 were important because they marked the end of British neutrality and isolationism.

Secrecy and suspicion

A Venn diagram depicting the network of alliances in 19th and 20th century Europe

Most alliances and ententes were formulated behind closed doors and revealed to the public after signing. Some nations even conducted negotiations without informing their other alliance partners. The German chancellor Bismarck, for example, initiated alliance negotiations with Russia in 1887, without informing Germany’s major ally Austria-Hungary.

A few alliances also contained ‘secret clauses’ that were not publicly announced or even revealed to other alliance partners. The 1882 Triple Alliance between Germany and Austria-Hungary, for example, contained a separate but secret agreement with Russia. Several of these concealed clauses only became known to the public after the end of World War I. The secretive nature of alliances only served to heighten suspicion and continental tensions.

An additional factor in the outbreak of World War I were small but significant changes to European alliances in the years prior to 1914. A clause inserted into the Dual Alliance in 1910, for example, required Germany to directly intervene if Austro-Hungary was ever attacked by Russia. These modifications strengthened and militarised alliances and probably increased the likelihood of war.

How significant were alliances?

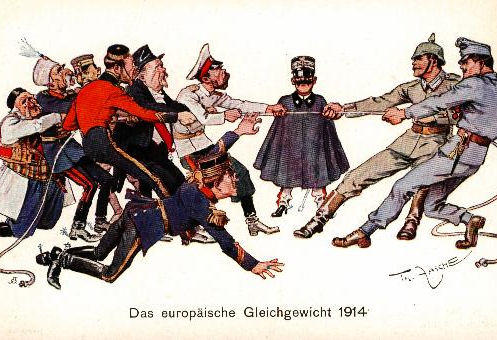

A depiction of the two alliance blocs, each pulling against the other

Despite these factors, the impact of the alliance system as a cause of war is often overstated. While alliances certainly contributed to rivalry, tension and perceptions that war was possible, they did not, as is often suggested, make war inevitable.

The reason for this is that alliances did not disempower governments or lead to automatic declarations of war. The authority and final decision to mobilise or declare war still rested with national leaders. It was their moral commitment to these alliances that was the telling factor. As historian Hew Strachan put it, the real problem was that by 1914, “nobody was prepared to fight wholeheartedly for peace as an end in itself.”

“Models of the war’s causality have often expressed contemporary international relations. During the Cold War and the division of the world into two, there was a tendency to view inter-national relations before 1914 as bipolar, and divided between two rigidly separated and rival blocs in which power, prestige and security were key determinants; and in which emphasis was placed on the alliance system in the war’s causes… Analysis turned on how far war was accidental (or ‘system generated’) and how far it was willed by governments.”

John Horne, historian

1. The alliance system was a network of treaties, agreements and ententes that were negotiated and signed prior to 1914.

2. National tensions and rivalries have made alliances a common feature of European politics, however the alliance system became particularly extensive in the late 1800s.

3. Many of these alliances were negotiated in secret or contained secret clauses, adding to the suspicion and tension that existed in pre-war Europe.

4. The Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy) formed the basis of the Central Powers, the dominant alliance bloc in central Europe.

5. Britain, France and Russia overcame their historical conflicts and tensions to form a three-way entente in the early 1900s.