Chapter 16: High Renaissance and Mannerism

Key Notes

- Time Period

- High Renaissance: 1495–1520; Rome

- Florence, Venice Mannerism: 1520–1600; Italy

- Culture, beliefs, and physical settings

- Renaissance art is generally the art of Western Europe.

- Renaissance art is influenced by the art of the classical world, Christianity, a greater respect for naturalism, and formal artistic training.

- Cultural interactions

- There are the beginnings of global commercial and artistic networks.

- Materials and Processes

- The period is dominated by an experimentation of visual elements, i.e., atmospheric perspective, a bold use of color, creative compositions, and an illusion of naturalism.

- Audience, functions, and patron

- There is a more pronounced identity and social status of the artist in society; the artist has more structured training opportunities.

- Theories and Interpretations

- Renaissance art is studied in chronological order.

- There is a large body of primary source material housed in libraries and public institutions.

Historical Background

- The High Renaissance blossomed in the sophisticated courts of kings, doges, and popes, each desiring to make his city-state larger than his neighbor's.

- The sack of Rome in 1527, a six-month rape of the city, put an end to much of this. Mannerism, a new art movement, evolved from Rome's ruins.

- Martin Luther started a theological and political revolution in Europe in 1517 when he nailed his theses to a church door in Wittenberg, Germany.

- The Protestant Reformation, considered a heretic in Italy, had a major effect on Italian art.

- No longer did the High Renaissance ideal of perfection reflect reality.

- In this difficult time, mannerist distortions were better.

- Mannerism's fundamental principles pit the ideal, natural, and symmetrical against the actual, artificial, and imbalanced.

- At the Council of Trent (1545–1563), Catholics responded to the Reformation's split with the Counter-Reformation.

- At the Council, the Jesuits were founded as a missionary and educational order.

- Art became a powerful educational tool and theological statement for the Jesuits, who became art collectors.

- In 1527, Rome was sacked, symbolizing the theological and political turmoil of the sixteenth century.

- The Holy Roman Empire's unpaid soldiers looted and pillaged the holy city after defeating the French in Italy.

- Rome's desecration shocked Christendom because it showed that its holiest site could be desecrated by the unruly and selfish.

Patronage and Artistic Life

- Renaissance painters like Titian and Michelangelo hailed from modest households.

- Artists joined trade guilds, which often made them appear like house painters or carpenters.

- However, artists may become so famous that rulers vied for their services.

- Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire praised Titian, Francis I of France held Leonardo da Vinci's dying body, and Michelangelo's biographers dubbed him "divino."

- Pope Julius II, a great European religious and political figure, was the era's patron.

- Julius's desire made Rome an artistic hub and Renaissance capital.

- Raphael and Michelangelo's best work was motivated by Julius's love of art.

- In 1563, Cosimo I of Florence founded the first permanent painting college to teach painters and elevate their reputation.

- However, the finest artists didn't require benefactors or academies.

- Although some chose to work for a duke and remain in his graces, a duke generally did not have enough assignments to keep a painter engaged.

- Most successful painters kept their main customers happy.

- Because Pope Julius II was Michelangelo's favourite client, their connection was prosperous.

- Mannerist artists found nothing wrong with this condition.

High Renaissance Painting

- Canvas proved durable and portable for Northern European painters.

- To reduce the cloth's influence on the paint, canvas was carefully prepared.

- Canvas had to be primed to simulate wood's enamel-like surface.

- Modern art keeps the gritty texture for its earthy vibe.

- Canvas: a heavy woven material used as the surface of a painting; first widely used in Venice

- Sfumato, a painting technique utilized by Leonardo da Vinci, created a hazy look by rendering figures softly.

- Sfumato places the topic in a foggy realm that distances us from it.

- Sfumato: a smoke-light or hazy effect that distances the viewer from the subject of a painting

- Chiaroscuro, which softens light and dark, was used by artists.

- By defining shapes with light, chiaroscuro enhances modeling effects.

- Chiaroscuro: a gradual transition from light to dark in a painting. Forms are not determined by sharp outlines, but by the meeting of lighter and darker areas

- Venetian painters, especially Titian, used glazes to enrich oil paintings.

- Since ancient times, glazes were employed to polish pottery.

- Glazes in pottery and painting are translucent to display the painted surface.

- Like varnish, glazes enhance colors.

- Glazes: thin transparent layers put over a painting to alter the color and build up a rich sonorous effect

- In portrait painting, three-quarter perspectives replaced quattrocento profiles.

- Profiles accentuate facial flaws.

- Portraits became psychological with Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa. A

- rtists were required to convey the sitter's personality.

- Raphael's idealization becomes the High Renaissance norm.

- Raphael's paintings were balanced, warm, and proportional.

- He preferred a triangle composition: the hefty bottom anchors forms tightly and then softens to a lighter touch as the viewer's eye ascends.

- Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper is a High Renaissance composition with the central figure, Jesus, alone and accentuated by the window behind.

- Jesus, the orthogonals' center, is symmetrically balanced by the twelve apostles in threes.

- Because of the Biblical drama on the characters' faces, the work's formal framework doesn't prevail.

➼ The Last Supper

Details

- Painted by Leonardo da Vinci

- 1494–1498

- Made of tempera and oil,

- Found in Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan

- Last Supper: a meal shared by Jesus Christ with his apostles the night before his death by crucifixion

Form

- Linear perspective; orthogonals of ceiling and floor point to Jesus.

- Apostles are grouped in sets of three

- Jesus is alone before a group of three windows, a symbol of the Trinity.

- A rounded pediment over Jesus’s head acts as a symbolic halo; Leonardo subtlety suggests Jesus’s divinity.

Function

- Painted for the refectory, or dining hall, of an abbey of friars.

- A relationship is drawn between the friars eating and a biblical meal.

Patronage: Commissioned by the Sforza family of Milan for the refectory of a Dominican abbey.

Materials

- Leonardo experimented with a combination of paints to yield a greater chiaroscuro.

- The paints began to peel off the wall in Leonardo’s lifetime.

- As a result, the painting has been restored many times and is a shadow of itself.

Content

- Great drama of the moment: Jesus says, “One of you will betray me” (Matthew 26:21); Jesus also blesses the bread and wine, creating a sacred Eucharist (Matthew 26:26–27).

- Various reactions on the faces of the apostles: surprise, fear, anger, denial, suspicion; anguish on the face of Jesus.

- Judas, the betrayer, falls back clutching his bag of coins; his face is symbolically in darkness.

Image

➼ Sistine Chapel Ceiling

Details

- By Michelangelo

- 1508–1512

- Made of fresco

- Found in Vatican City, Italy

Form

- Masculine modeling of forms.

- Bold, direct, powerful narrative expression.

Function

- Function of the chapel: the place where new popes are elected and where papal services take place.

- Name derives from Pope Sixtus IV, who was the patron of the building’s redesign between 1473 and 1481.

Content

- Michelangelo chose a complicated arrangement of figures for the ceiling, which broadly illustrates the first few chapters of Genesis in nine scenes, with accompanying Old Testament figures and antique sibyls

- The grand and massive figures are meant to be seen from a distance, but also echo the grandeur of the Biblical narrative.

- 300 figures on the ceiling, with no two in the same pose; a tribute to Michelangelo’s lifelong preoccupation with the male nude in motion.

- Enormous variety of expression.

- Painted cornices frame groupings of figures in a highly organized way.

- Many figures are done for artistic expression rather than to enhance the narrative; the ignudi, for example.

- Ignudi: nude corner figures on the Sistine Chapel ceiling

Context

- Sistine Chapel was erected in 1472 and painted by quattrocento masters, including Botticelli, Perugino, and Michelangelo’s teacher, Ghirlandaio.

- Quattrocento paintings are of the life of Christ and the life of Moses; Michelangelo needed a different topic for the ceiling; he chose the cosmic theme of creation.

- Michelangelo’s paintings are painted over the window level of the chapel as well as the ceiling.

- The chapel is dedicated to the Virgin Mary, as such the central panel on the ceiling depicts Eve, the archetype of Mary, who, according to tradition, began the redemption necessitated by the sin of Eve and Adam.

- Acorns, a motif on the ceiling, were inspired by the crest of the chapel’s patron, Pope Julius II.

Images

➼ Delphic Sybil

Details

- By Michelangelo

- 1508–1512

- Made of fresco

- Found in Vatican City, Italy

- Sibyl: a Greco-Roman prophetess whom Christians saw as prefiguring the coming of Jesus Christ

Form and Content

- The sibyl wears a Greek-style turban.

- Her head is turned as if listening.

- She has a sorrowful expression.

- There is a dramatic contrapposto positioning of the body.

- She holds the scroll containing her prophecy.

- She is a powerfully built female figure.

Context

- One of five sibyls (prophetesses) on the ceiling.

- Greco-Roman figures whom Christians believed foretold the coming of Jesus Christ.

- This shows a combination of Christian religious and pagan mythological imagery.

Image

➼ The Flood

Details

- By Micheangelo

- 1508–1512

- Made of fresco

- Found in Vatican City, Italy

- Flood story: as told in Genesis 7 of the Bible, Noah and his family escape rising waters by building an ark and placing two of every animal aboard

Form

- Sculptural intensity of the figure style.

- More than 60 figures are crowded into the composition.

Function: One of the scenes on the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

Content

- Story details Noah and his family’s escape from rising floodwaters, as told in Genesis 7.

- The few remaining survivors cling to mountain tops; their fate will be sealed.

- A man carrying his drowned son to safety will meet his son’s fate as well.

- The ark in the background is the only safe haven.

- The salvation of the good (as opposed to God’s destruction of the wicked) is stressed.

Image

➼ Last Judgment

Details

- By Michelangelo

- 1536–1541

- Made of fresco

- Found in Vatican City, Italy

Form

- In contrast to the ceiling, there are no cornice divisions; it is one large space with figures greatly integrated.

- The Mannerist style is shown in the distortions of the body: elongations and crowded groups.

Function

- Last Judgment scenes are traditional on altar walls of chapels

- This was not the original choice of subject matter for the wall.

Patronage: Pope Paul III was the patron.

Context

- The subject was chosen because of the turbulence in Rome after the sack of the city in 1521.

- Counter-Reformation message: the true path to salvation is through the Catholic Church.

- Spiraling composition is a reaction against the High Renaissance harmony of the Sistine Ceiling and reflects the disunity in Christendom caused by the Reformation.

- In the spirit of the Counter-Reformation, the genitalia were painted over after Michelangelo’s death.

Content

- Four broad horizontal bands act as the unifying element:

- Bottom: dead rising on the left and the mouth of hell on the right.

- Second level: ascending elect, descending sinners, trumpeting angels.

- Third level: those risen to heaven are gathered around Jesus.

- Top lunettes: angels carrying the cross and the column, instruments used at Christ’s death.

- Christ, in center, gestures defiantly with right hand; complex pose.

- Justice is delivered: the good rise, the evil fall.

- Lower right-hand corner has figures from Dante’s Inferno: Minos and Charon.

- Saint Bartholomew’s face is modeled on a contemporary critic.

- Saint Bartholomew holds his skin, a symbol of his martyrdom, but the skin’s face is Michelangelo’s, an oblique reference to critics who skinned him alive with their criticism.

- It may also represent Michelangelo’s concern over the fate of his soul as expressed in his poetry.

Image

➼ School of Athens

Details

- By Raphael

- 1509–1511

- Made of fresco

- Found in Apostolic Palace, Vatican City, Italy

Form

- Open, clear light uniformly spread throughout the composition.

- Nobility and monumentality of forms parallel the greatness of the figures represented; figures gesture to indicate their philosophical thought.

- Raphael’s overall composition was influenced by Leonardo’s Last Supper

Patronage and Function

- Commissioned by Pope Julius II to decorate his library.

- This is one painting in a complex program of works that illustrate the vastness and variety of the papal library.

- Painting originally called Philosophy because the pope’s philosophy books were meant to be housed on shelving below.

Content and Context

- Opposite this work is a Raphael painting called La Disputà,

- based on religion;

- religious books were placed below;

- parallels drawn between the two themes expressed in the paintings.

- To the left of Philosophy is Apollo and the Muses on Parnassus, referencing literature.

- The building depicted in the background might reflect Bramante’s plan for Saint Peter’s; Bramante appears as the bald Euclid in the lower right.

- In the center are the two greatest figures in ancient Greek thought:

- Plato (with the features of Leonardo da Vinci) on the left pointing up, and

- Aristotle (perhaps with the features of the architect Giuliano da Sangallo) pointing out.

- Their gestures reflect their philosophies.

- On the left are those interested in the ideal (followers of Plato); on the right, those interested in the practical (followers of Aristotle).

- Raphael is on the extreme right with a black hat.

- Michelangelo, resting on the stone block writing a poem, represents the philosopher Heraclitus; the figure was added later and was not part of the original composition.

Image

Venetian High Renaissance Painting

- Unlike the Florentines and Romans, who prized line and contour, the Venetians bathed their figures in a gentle ambient ambience accented by softly modulated light.

- Bodies are sensual.

- While Florentines and Venetians both paint religious subjects, Florentines consider them as heroic feats, while Venetians humanize their saints and put them in pastoral settings that reflect a true love in the beauty of nature. It's called Arcadian.

- Arcadian: a simple rural and rustic setting used especially in Venetian paintings of the High Renaissance; named after Arcadia

- Arcadia: a district in Greece to which poets and painters have attributed a rural simplicity and an idyllically untroubled world

- The wet Venetian environment caused wooden paintings to warp and fracture and frescoes to peel and flake.

- Canvas, a stronger, lighter surface, was chosen by artists.

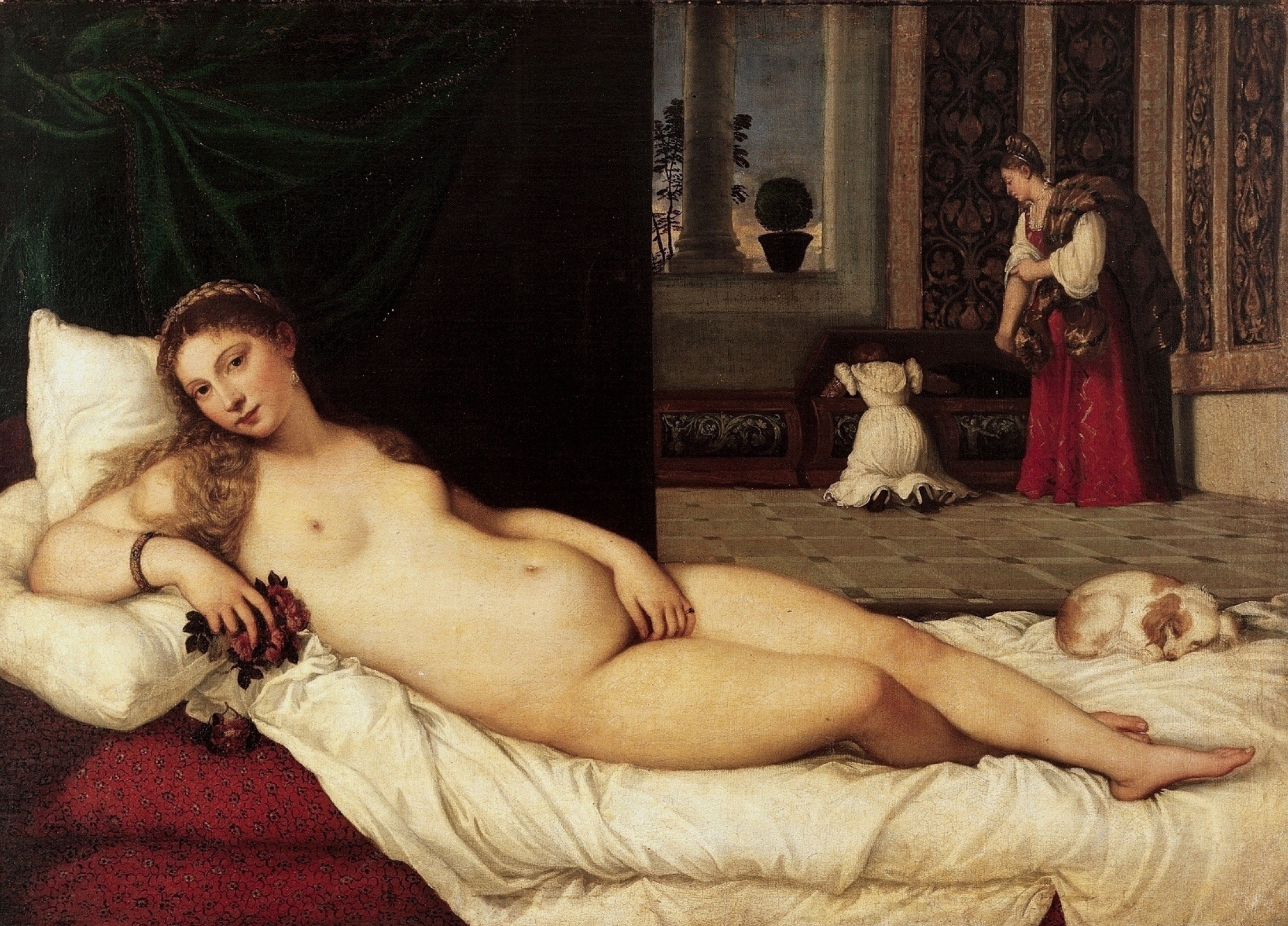

➼ Venus of Urbino

Details

- By Titian

- 1538

- Made of oil in cavas

- Found in Uffizi, Florence

Form

- Sensuous delight in the skin tones; layers of glazes produce rich, sonorous effect.

- Oil painted in layers; glazes achieve rich color.

- Complex spatial environment: figure placed forward on the picture plane, servants in middle space; open window with plants in background.

Content

- Venus looks at the viewer directly.

- Venus is reclining in an open space in a luxurious Venetian bedroom.

- Roses contribute to the floral motif carried throughout the work; roses with their thorns symbolize the beauty and problems of love.

- The dog may symbolize faithfulness.

Context

- May not be Venus; may be a courtesan in the tradition of a female reclining nude.

- Cassoni: trunks intended for storage of clothing for a wife’s trousseau seen in the background of the painting.

- May have been commissioned by the Duke of Urbino as a wedding painting.

Image

Mannerist Painting

- Mannerists used perspective to create an appealing illusion or let the eye roam across a picture plane, as in Pontormo's Entombment.

- Entombment: a painting or sculpture depicting Jesus Christ’s burial after his crucifixion

- Although largely indebted to High Renaissance forms, the Mannerist utilizes them as starting points to freely change the goals of the preceding age.

- The Mannerists' ability to resist traditional order and logic makes the style appealing.

- Still life emerges in Mannerist painting.

- Still life: a painting of a grouping of inanimate objects, such as flowers or fruit

- It becomes acceptable in seventeenth-century Holland while being considered the lowest type of painting.

- Genre painting: painting in which scenes of everyday life are depicted

- Scholars saw Mannerist paintings' complex compositions as primitive remnants of High Renaissance art.

- Mannerist art's artifice—its peculiar intricacies and confusing spaces—has grown on historians.

- This cerebral art genre seeks refinement in strange compositions and artificial circumstances.

- Exaggerated shapes, opaque imagery, and symbolic enigmas create illogical spatial effects that are intriguing, exciting, and demanding.

- Mannerist painting's worth lies in its deliberate ambiguity.

➼ Entombment of Christ

Details

- By Jacopo da Pontormo

- 1525–1528

- Made of oil on wood

- Found in Santa Felicità, Florence

Form

- Anticlassical composition.

- Linear bodies twisting around one another.

- In the center of the circular composition is a grouping of hands.

- Hands seem disembodied.

- No ground line for many figures; what is Mary sitting on?

- Elongation of bodies.

- Some androgynous figures.

- No weeping, just yearning.

- High-keyed colors, perhaps taking into account the darkness of the chapel the work is placed in.

Context

- The painting is called Entombment of Christ, although there is no tomb, just the carrying of Jesus’s lifeless body.

- It is placed over the altar of a family chapel near the right front entrance of Santa Felicità in Florence.

- The composition and Mannerist style may reflect the instability in European politics brought on by the Protestant Reformation.

- There is a self-portrait on the extreme right of the painting.

Image

Mannerist Architecture

- Mannerist architects creatively utilize ancient features without regard to their intended use.

- These are often seen in works that boldly interweave classical features to make us consider the Renaissance's importance of ancient building.

➼ II Gesù

Details

- By Giacomo della Porta

- 1568–1584

- Made of brick and marble

- Nave by Giacomo da Vignola, 16th century

Form Façade:

- Column groupings, tympana, and pediment emphasize the central doorway.

- A slight crescendo of forms directs the viewer to the center.

- The two stories separated by a cornice; united by scrolls and a framing niche.

- The letters of Jesus’s name (IHS) are over the central doorway in a cartouche.

- Patron: Cardinal Farnese has his name placed directly over the cartouche with Jesus’s name.

Form Interior:

- Interior has no aisles; meant for grand ceremonies.

- Ceiling painting

Function: Principal church of the Jesuit order.

Context: Jesuits are seen as the defenders of Counter-Reformation ideals.

Images