Chapter 8: Byzantine Art

Key Notes

- Time Period

- Early Byzantine : 500–726

- Iconoclastic Controversy : 726–843

- Middle and Late Byzantine : 843–1453, and beyond

- Culture, beliefs, and physical settings

- Byzantine art is a medieval tradition.

- Byzantine art is inspired by the requirements of Christian worship.

- Byzantine art avoids naturalism and incorporates text into its images.

- Art Making

- Works of art were often displayed in religious and royal settings.

- Surviving architecture is mostly religious.

- Often there were reactions against figural imagery.

- Theories and Interpretations

- The study of art history is shaped by changing analyses based on scholarship, theories, context, and written records.

- Contextual information comes from written records that are religious or civic.

Historical Background

- The Byzantine Empire was born from a split in the Roman world that occurred in the fifth century, when the size of the Roman Empire became too unwieldy for one ruler to manage effectively.

- The fortunes of the two halves of the Roman Empire could not have been more different.

- The western half dissolved into barbarian chaos, succumbing to hordes of migrating peoples.

- The eastern half, founded by Roman Emperor Constantine the Great at Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), flourished for one-thousand years beyond the collapse of its western counterparts.

- Byzantines spoke Greek instead of Latin and promoted orthodox Christianity instead of western Christianity, which was centered in Rome.

- The porous borders of the Empire expanded and contracted during the Middle Ages, reacting to external pressures from invading armies, seemingly coming from all directions.

- The Empire had only itself to blame: The capital, with its unparalleled wealth and opulence, was the envy of every other culture.

- Its buildings and public spaces awed ambassadors from around the known world.

- Constantinople was the trading center of early medieval Europe, directing traffic in the Mediterranean and controlling the shipment of goods nearly everywhere.

- Icon production was a Byzantine specialty.

- Devout Christians attest that icons are images that act as reminders to the faithful; they are not intended to actually be the sacred persons themselves.

- However, by the eighth century, Byzantines became embroiled in a heated debate over icons; some even worshipped them as idols.

- In order to stop this practice, which many considered sacrilegious, the emperor banned all image production.

- Iconoclasts also destroyed images.

- Iconoclasts may have been inspired by Judaism and Islam, which forbade images of sacred figures for similar reasons.

- The unfortunate result of this activity is that art from the Early Byzantine period (500–726) is almost completely lost.

- The artists themselves fled to parts of Europe where iconoclasm was unknown and Byzantine artists welcome.

- This so-called Iconoclastic Controversy serves as a division between the Early and Middle Byzantine art periods.

- Iconoclastic controversy: the destruction of religious images in the Byzantine Empire during the eighth and ninth centuries.

- Despite the iconoclasts' early successes, it became harder to suppress images in a Mediterranean culture like Byzantium that had a long history of painting and sculpting gods before the Greeks.

- In 843, iconoclasm was repealed and images were reinstated.

- This meant that every church and monastery had to be redecorated, causing a burst of creative energy throughout Byzantium.

- Medieval Crusaders, some more interested in the spoils of war than the restoration of the Holy Land, conquered Constantinople in 1204, setting up a Latin kingdom in the east.

- Eventually the Latin invaders were expelled, but not before they brought untold damage to the capital, carrying off to Europe precious artwork that was simultaneously booty and artistic inspiration.

- The invaders also succeeded in permanently weakening the Empire, making it ripe for the Ottoman conquest in 1453.

- Even so, Late Byzantine artists continued to flourish both inside what was left of the Empire and in areas beyond its borders that accepted orthodoxy.

- A particularly strong tradition was established in Russia, where it remained until the 1917 Russian Revolution ended most religious activity.

- Even rival states, like Sicily and Venice, were known for their vibrant schools of Byzantine art, importing artists from the capital itself.

Patronage and Artistic Life

- In the Byzantine Empire, church and state were one, therefore many of the finest works of art were commissioned by both.

- Monasteries commissioned several private works. Religious works competed for space in Byzantine structures.

- Luxury-loving royals built a powerful court atelier.

- Luxury ivory, manuscript, and precious metal crafts were this atelier's specialty.

- Artists believed they were creating works for God. Pride was a sin, thus they seldom signed their names.

- Many painters were monks, priests, or nuns whose work reflected their faith.

Byzantine Architecture

- Byzantine architecture shows great innovation, beginning with the construction of the Hagia Sophia in 532 in Istanbul.

- The architects, Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus examined the issue of how a round dome, such as the one built for the Pantheon in Rome could be placed on flat walls.

- Their solution was the invention of the pendentive, a triangle-shaped piece of masonry with the dome resting on one long side, and the other two sides channeling the weight down to a pier below.

- A pendentive supports the dome on four corner piers.

- Since the walls between the piers do not support the dome, they can be opened for more window space.

- The Hagia Sophia has windows on each side, unlike the Pantheon, which has only an oculus in the dome.

- Middle and Late Byzantine architects introduced a variation on the pendentive called the squinch.

- Squinch: the polygonal base of a dome that makes a transition from the round dome to a flat wall

- The Hagia Sophia’s dome is composed of a set of ribs meeting at the top.

- The spaces between those ribs do not support the dome and are opened for window space.

- The Hagia Sophia's forty windows form a halo over the congregation.

- Churches in the Early Christian era concentrate on one of two forms: the circular building containing a centrally planned apse and the longer basilica with an axially planned nave facing an altar.

- The Hagia Sophia's dome emphasizes a central core and the long nave draws attention to the apse.

- Buildings in the Early period (500–726) have plain exteriors made of brick or concrete.

- In the Middle and Late periods (843–1453), the exteriors are richly articulated with a provocative use of various colors of brick, stone, and marble, often with contrasting vertical and horizontal elements.

- The domes are smaller, but there are more of them, sometimes forming a cross shape.

- Interiors feature mosaics or frescoes on upper floors and marbles of various colors on lower floors.

- Windows surround dome bases, making them low.

- Half-lights and shimmering mosaics create mysterious spaces inside arches.

- These buildings usually set the domes on more elevated drums.

- Greek Orthodox tradition dictates that important parts of the Mass take place behind a curtain or screen.

- In some buildings this screen is composed of a wall of icons called an iconostasis.

- Iconostasis: a screen decorated with icons, which separates the apse from the transept of a church

- Cathedral: the principal church of a diocese, where a bishop sits

- Icon: a devotional panel depicting a sacred image

➼ Hagia Sophia

Details

- By Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus,

- 532–537

- Made of brick and ceramic elements, with stone and mosaic veneer,

- Found in Constantinople (Istanbul)

Form Exterior: plain and massive with little decoration.

Form Interior:

- Combination of centrally and axially planned church.

- Arcade decoration: walls and capitals are flat and thin and richly ornamented.

- Capitals diminish classical allusions; surfaces contain deeply cut acanthus leaves.

- Cornice unifies space.

- Cornice: a projecting ledge over a wall

- Large fields for mosaic decoration; at one time there were four acres of gold mosaics on the walls. –Many windows punctuate wall spaces.

- Dome: the first building to have a dome supported by pendentives.

- Altar at end of nave, but the emphasis placed over the area covered by the dome.

- Large central dome, with 40 windows at base symbolically acting as a halo over the congregation when filled with light.

Function

- Originally a Christian church; Hagia Sophia means “holy wisdom.”

- Built on the site of another church that was destroyed during the Nike Revolt in 532.

- Converted to a mosque in the fifteenth century; minarets added in the Islamic period.

- Converted into a museum in 1935; reconverted into a mosque in 2020.

Context

- Marble columns appropriated from Rome, Ephesus, and other Greek sites.

- Patrons were Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora, who commissioned the work after the burning of the original building in the Nike Revolt.

Image

➼ San Vitale

Details

- Early Byzantine Europe

- 526–547

- Made of brick, marble, and stone veneer

- Found in Ravenna, Italy

Form

- Eight-sided church.

- Plain exterior; porch added later, in the Renaissance.

- Large windows for illuminating interior designs.

- Interior has thin columns and open arched spaces.

- Dematerialization of the mass of the structure.

- Combination of axial and central plans.

- Spolia: bricks taken from ruined Roman buildings reused here.

- Martyrium design: circular plan in an octagonal format.

- Martyrium: a shrine built over a place of martyrdom or a grave of a martyred Christian saint

Function: Christian church.

Context

- Mysterious space symbolically connects with the mystic elements of religion.

- Banker Julianus Argentarius financed the building of San Vitale.

Image

Byzantine Painting

- The most characteristic work of Byzantine art is the icon, a religious devotional image usually of portable size and hanging in a place of honor either at home or in a religious institution.

- An icon has a wooden foundation covered by preparatory undercoats of paint, sometimes composed of such things as fish glue or putty.

- Cloth is placed over this base, and successive layers of stucco are gently applied.

- A perforated paper sketch is placed on the surface, so that the image can be traced and then gilded and painted.

- The artist then applies varnish to make the icon shine, as well as to protect it, because icons are often touched, handled, and embraced.

- Icons have been blackened by candle soot and incense, and their frames burned by votive candles.

- Thus, many icons have been repainted and lost their texture.

- Icons were displayed on city walls during invasions and paraded on feast days.

- Byzantine worshippers revered them as spiritual beings.

- Byzantine painting combines classical Greece and Rome with a hieratic medieval style.

- Many artists work on the same piece, some inspired by classical tradition and others by medieval formalism.

- The Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George shows both traditions.

- Theotokos: the Virgin Mary in her role as the Mother of God

- Classically trained artists depicted figures from unusual angles with painterly brushstrokes.

- These artists used soft color transitions and relaxed figure stances.

- Those trained in the medieval tradition favored frontal poses, symmetry, and almost weightless bodies.

- The drapery is emphasized, so there is little effort to reveal the body beneath.

- Perspective is unimportant because figures occupy a timeless space, marked by golden backgrounds and heavily highlighted halos.

- Whatever the tradition, Byzantine art, like all medieval art, avoids nudity whenever possible, deeming it debasing.

- Nudity also had a pagan association, connected with the mythological religions of ancient Greece and Rome.

- One of the glories of Byzantine art is its jewel-like treatment of manuscript painting.

- The manuscript painter had to possess a fine eye for detail, and so was trained to work with great precision, rendering minute details carefully.

- Byzantine manuscripts are meticulously executed; most employ the same use of gold seen in icons and mosaics.

- Because so few people could read, the possession of manuscripts was a status symbol, and libraries were true temples of learning.

- The Vienna Genesis is an excellent example of the sophisticated court style of manuscript painting.

- Byzantine art continues the ancient traditions of fresco and mosaic painting, bringing the latter to new heights.

- Interior church walls are covered in shimmering tesserae made of gold, colored stones, and glass.

- Each piece of tesserae is placed at an odd angle to catch the flickering of candles or oblique sunlight, creating a glittering world of floating golden shapes that may have resembled heaven to the Byzantines.

- Court customs play an important role in Byzantine art.

- Purple, the color usually reserved for Byzantine royalty, can be seen in the mosaics of Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora.

- However, in an act of transference, purple is sometimes used on the garments of Jesus himself.

- Custom at court prescribed that courtiers approach the emperor with their hands covered as a sign of respect.

- As a result, nearly every figure has at least one hand covered before someone of higher station, sometimes even when he or she is holding something.

- Justinian himself, in his famous mosaic in San Vitale, holds a paten with his covered hand.

- Paten: a plate, dish, or bowl used to hold the Eucharist at a Christian ceremony

- Facial types are fairly standardized.

- There is no attempt at psychological penetration or individual insight: Portraits in the modern sense of the word are unknown.

- Continuing a tradition from Roman art, eyes are characteristically large and wide open.

- Noses tend to be long and thin, mouths short and closed.

- The Christ Child, who is a fixture in Byzantine art, is more like a little man than a child, perhaps showing his wisdom and majesty.

- Medieval art generally labels the names of figures the viewer is observing, and Byzantine art is no exception.

- Most paintings have flat backgrounds with one gold layer to symbolize eternity.

- In the Middle and Late Byzantine periods, figures stand before a monochromatic of golden opulence, suggesting a heavenly world.

- Codex (plural: codices): a manuscript book

➼ Justinian Panel

Details

- c. 547

- A mosaic

- From San Vitale, Ravenna

Content

- Emperor Justinian, as the central image, dominates all; emperor’s rank indicated by his centrality, halo, fibula, and crown.

- To his left the clergy, to his right the military.

- Dressed in royal purple and gold.

- Divine authority symbolized by the halo; Justinian is establishing religious and political control over Ravenna.

Form

- Symmetry, frontality.

- Slight impression of procession forward.

- Figures have no volume; they seem to float and yet step on each other’s feet.

- Minimal background: green base at feet; golden background indicates timelessness.

Function

- Justinian holds a paten, or plate, for the Eucharist; participating in the service of the Mass almost as if he were a celebrant—his position over the altar enhances this reference.

- Eucharist: the bread sanctified by the priest at the Christian ceremony commemorating the Last Supper

- Justinian appears as head of church and state; regent of Christ on earth.

Context

- Archbishop Maximianus is identified; he is the patron of San Vitale.

- XP or Chi Rho, the monogram of Christ, on soldier’s shield shows them as defenders of the faith, or Christ’s soldiers on earth.

- XP: the Christian monogram made up of the Greek letters khi and rho, the first two letters of Khristos, the Greek form of Christ’s name

Image

➼ Theodora Panel

Details

- c. 547

- A mosaic

- From San Vitale, Ravenna

Content

- Empress Theodora stands in an architectural framework holding a chalice for the Mass and is about to go behind the curtain.

- Chalice: a cup containing wine, used during a Christian service

Form

- Slight displacement of absolute symmetry with Empress Theodora; she plays a secondary role to her husband.

- She is simultaneously frontal and moving to our left.

- Figures are flattened and weightless; barely a hint of a body can be detected beneath the drapery.

Function

- She holds a chalice for the wine; participating in the service of the Mass almost as if she were a celebrant.

- She is juxtaposed with Emperor Justinian on the flanking wall; both figures hold the sacred items for the Mass.

Context

- Richly robed empress and ladies at court.

- The three Magi, who bring gifts to the baby Jesus, are depicted on the hem of her dress.

- This reference draws parallels between Theodora and the Magi.

Image

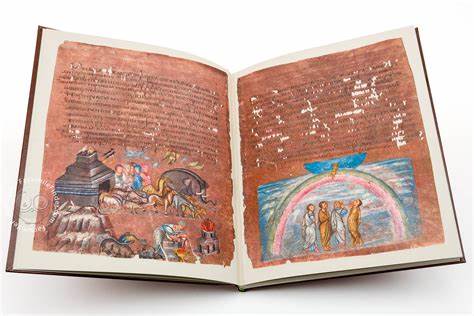

➼ Vienna Genesis

Details

- Early Byzantine Europe

- Early 6th century

- An illuminated manuscript, tempera, gold, and silver on purple vellum, Austrian National Library, Vienna

- Genesis: first book of the Bible that details Creation, the Flood, Rebecca at the Well, and Jacob Wrestling the Angel, among other episodes

- Illuminated manuscript: a manuscript that is hand decorated with painted initials, marginal illustrations, and larger images that add a pictorial element to the written text

Form

- Lively, softly modeled figures.

- Classical training of the artists: contrapposto, foreshortening, shadowing, perspective, classical allusions.

- Shallow settings.

- Fluid movement of decorative figures.

- Richly colored and shaded.

- Two rows linked by a bridge or a pathway.

- Text placed above illustrations, which are on the lower half of the page.

- Continuous narrative.

Context

- First surviving illustrations of the stories from Genesis.

- Genesis stories are done in continuous narrative with genre details.

- Written in Greek.

- Partial manuscript: 48 of 192 (?) illustrations survive.

Materials and Origin

- Manuscript painted on vellum.

- Written in silver script, now oxidized and turned black.

- Origin uncertain: a scriptorium in Constantinople? Antioch?

- Perhaps done in a royal workshop; purple parchment is a hallmark of a royal institution.

Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well

- Genesis 24: 15–61.

- Rebecca, shown twice, emerges from the city of Nahor with a jar on her shoulder to go down to the spring.

- She quenches the thirst of a camel driver, Eliezer, and his camels.

- Colonnaded road leads to the spring.

- Roman water goddess personifies the spring.

Jacob Wrestling the Angel

- Genesis 32: 22–31.

- Jacob takes his two wives, two maids, and eleven children and crosses a river; the number of children is abbreviated.

- At night Jacob wrestles an angel.

- The angel strikes Jacob on the hip socket.

- Classical influence in the Roman-designed bridge, but medieval influence in the bridge’s perspective: i.e., the shorter columns are placed in the nearer side of the bridge and the taller columns behind the figures.

Images

➼ Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George

Details

- Early Byzantine Europe

- 6th or early 7th centuries

- Encaustic on wood

- Found in Monastery of Saint Catherine, Mount Sinai, Egypt

- Encaustic: a type of painting in which colors are added to hot wax to affix to a surface.

Function

- Icon placed in a medieval monastery for devotional purposes.

Content and Form

- Virgin and Child centrally placed; firmly modeled.

- Mary as Theotokos, mother of God.

- Mary looks beyond the viewer as if seeing into the future.

- Christ child looks away, perhaps anticipating his crucifixion.

- Saints Theodore and George flank Virgin and Child.

- Warrior saints.

- Stiff and hieratic.

- Directly stare at the viewer; engage the viewer directly.

- Angels in background look toward heaven.

- Painted in a classical style with brisk brushwork in encaustic, a Roman tradition.

- Turned toward the descending hand of God, which comes down to bless the scene.

- Because the three groups are in very different styles, it has been assumed that they were painted by three different artists.

Context

- Pre–Iconoclastic Controversy icon, located in the Sinai and encaustic places it near Roman-Egyptian encaustic painted portraits.

Image