Unit 9: The Pacific, 700-1980 CE

Contextualization of Pacific Art

Some areas of the Pacific are among the oldest inhabited places on earth, while others are among the newest.

Aborigines reached Australia around 50,000 years ago.

Remote Pacific islands like Hawaii, Easter Island, and New Zealand were occupied only in the last thousand years.

Seafarers reached Fiji in the central South Pacific around 1300 B.C.E.

Technological development of sailing craft enabled greater territories to be mapped and charted for possible occupation.

Tonga was reached in 420 B.C.E. and Samoa in 200 B.C.E. using the particularly effective twin-hulled sailing canoe.

The discovery of New Zealand by the ancestors of the Maori happened perhaps as early as the tenth century, but certainly by the thirteenth century.

European involvement in the Pacific began with the circumnavigation of the globe by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan and his crew.

Explorers of the eighteenth century were followed by occupiers from the nineteenth century, who implanted European customs, values, religions, and technologies onto the indigenous population.

Many areas of the Pacific achieved independence in the twentieth century.

Materials, Processes, and Techniques in Pacific Art

Materials

They use natural materials such as wood, bark, shells, feathers, and fibers.

These materials are often sourced from the local environment and have cultural significance to the communities that use them.

Wood is a particularly important material in Pacific art, used for carving sculptures, masks, and canoes.

Bark cloth, made from the inner bark of trees, is used for clothing, bedding, and ceremonial purposes.

Shells and feathers are used for adornment and decoration.

Processes

Carving is a common technique used to create sculptures, masks, and canoes. It involves using chisels and other tools to shape wood into the desired form.

Weaving is another important process in Pacific art, used to create baskets, mats, and clothing. It involves interlacing fibers or other materials to create a pattern or structure.

Painting is also used in Pacific art, often to decorate carvings or bark cloth.

Techniques

Pacific art is characterized by a range of techniques that are specific to different cultures and regions.

For example, in Maori culture, the technique of "whakairo" involves carving intricate patterns and designs into wood.

In Papua New Guinea, the "bilum" technique is used to create woven bags and baskets using a looping technique.

In Fiji, the "masi" technique is used to create bark cloth by pounding and stretching the inner bark of trees.

These techniques are often passed down through generations and have cultural significance to the communities that use them.

Theories and Interpretations of Pacific Art

Pacific art is often tied to cultural and spiritual beliefs, and can be used for communication and storytelling.

Theories of Pacific art include functionalism, formalism, and symbolism.

Interpretations of Pacific art can vary depending on the perspective of the viewer, and can be influenced by factors such as colonialism and globalization.

Some key examples of Pacific art include tapa cloth, wood carvings, and tattooing.

Pacific Artworks

➼ Nan Madol

Details

Saudeleur Dynasty

c. 700–1600

basalt boulders and prismatic columns

Found in Pohnpei, Micronesia

Form

92 small artificial islands connected by canals, about 170 acres in total.

Built out into the water on a lagoon—similar to Venice, Italy.

Seawalls 15 feet high and 35 feet thick acted as breakwaters.

Canals were flushed clean with the tides.

Islands were arranged southwest to northeast to take advantage of the trade winds.

Walls were made of prismatic basalt; roofs were thatched.

Function: Ancient city that acted as the capital of the Saudeleur Dynasty of Micronesia.

Context

City built to separate the upper classes from the lower classes.

King arranged for the upper classes to live close to him, to keep an eye on them.

Curved outer walls point upward at edges, giving the complex a symbolic boat-like appearance.

➼ Female Deity

Details

c. 18th to 19th century

Wood

Found in Nukuoro, Micronesia

Form

Simple geometric form.

Erect pose, long arms, broad chest.

Chin drawing to a point; no facial features.

Horizontal lines were used to indicate kneecaps, navel, and waistline.

Function: Female deity.

Context

Many were kept in religious buildings belonging to the community.

They represent individual deities.

Sometimes they were dressed in garments; may have been decorated with flowers.

Taken by missionaries who did not record anything about the sculptures.

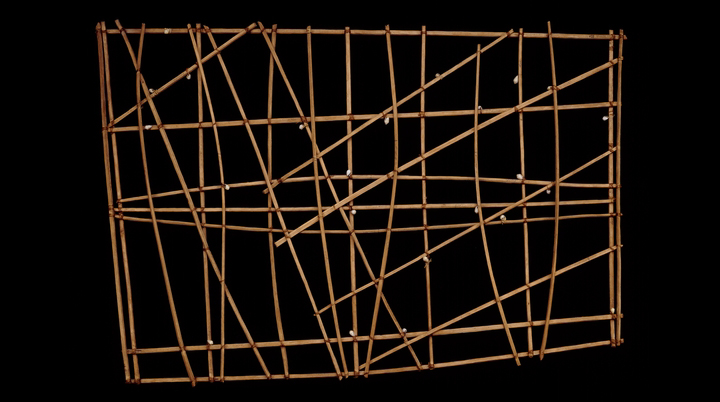

➼ Navigation Chart

Details

From Marshall Islands, Micronesia

19th to early 20th century

wood and fiber

British Museum, London

Form

Chart is made of wood, therefore waterproof and buoyant.

Small shells indicate the position of the islands on the chart.

Horizontal and vertical sticks support the chart.

Diagonal lines indicate wind and water currents.

Charts indicate patterns of ocean swells and currents.

Function

Charts meant to be memorized prior to a voyage; not necessarily used during a voyage.

Charts enabled navigators to guide boats through the many islands to get to a destination. Charts were individualized to their makers; others cannot read the chart.

Context

Marshall Islands are low lying and hard to see from a distance or from sea level.

Charts are called wapepe in the Marshall Islands.

➼ ‘Ahu ‘ula (Feather Cape)

Details

late 18th century

feathers and fiber,

Found in British Museum, London

Materials

The cape is made of thousands of bird feathers.

Feathers numbered 500,000; some birds had only seven usable feathers.

The feathers were tied to a coconut fiber base.

Function: Only high-ranking chiefs or warriors of great ability were entitled to wear these garments; worn by men.

Context

Red was considered a royal color in Polynesia; yellow was prized because of its rarity.

The cape was created by artists who chanted the wearer’s ancestors to imbue their power onto it.

It protected the wearer from harm.

The concept of “mana:” a supernatural force believed to dwell in a person or sacred object.

Many capes have survived, but no two capes are alike.

➼ Staff God

Details

From Rarotonga, Cook Islands, central Polynesia

late 18th to early 19th century

wood, tapa, fiber, and feathers

Found in British Museum, London

Form and Content

Large, column-like, wooden core mounted upright in village common spaces; the wooden core is wrapped with tapa cloth.

The wooden sculpture placed on top features a large carved head with several smaller figures carved below it).

The shaft is in the form of an elongated body.

The lower end had a carved phallus. Some missionaries removed and destroyed the phalluses, considering them obscene.

The soul of the god is represented by polished pearl shells and red feathers, which are placed inside the bark cloth next to the interior shaft.

Context

Most staff gods were destroyed; only the top ends were retained as trophies.

This is the only surviving wrapped example of a staff god.

In the contextual image from a book by an English missionary (not shown), the staff gods have been thrown down in the village square in front of a European-style church; it represents the fall of one faith and the adoption of another.

The contextual image is the only visual evidence that indicates how these staff gods were used.

Reverend John Williams observed that the barkcloth contained red feathers and pieces of pearl shell, known as the manava or the spirit of the god. He also recorded seeing the islanders carrying the image upright on a litter.

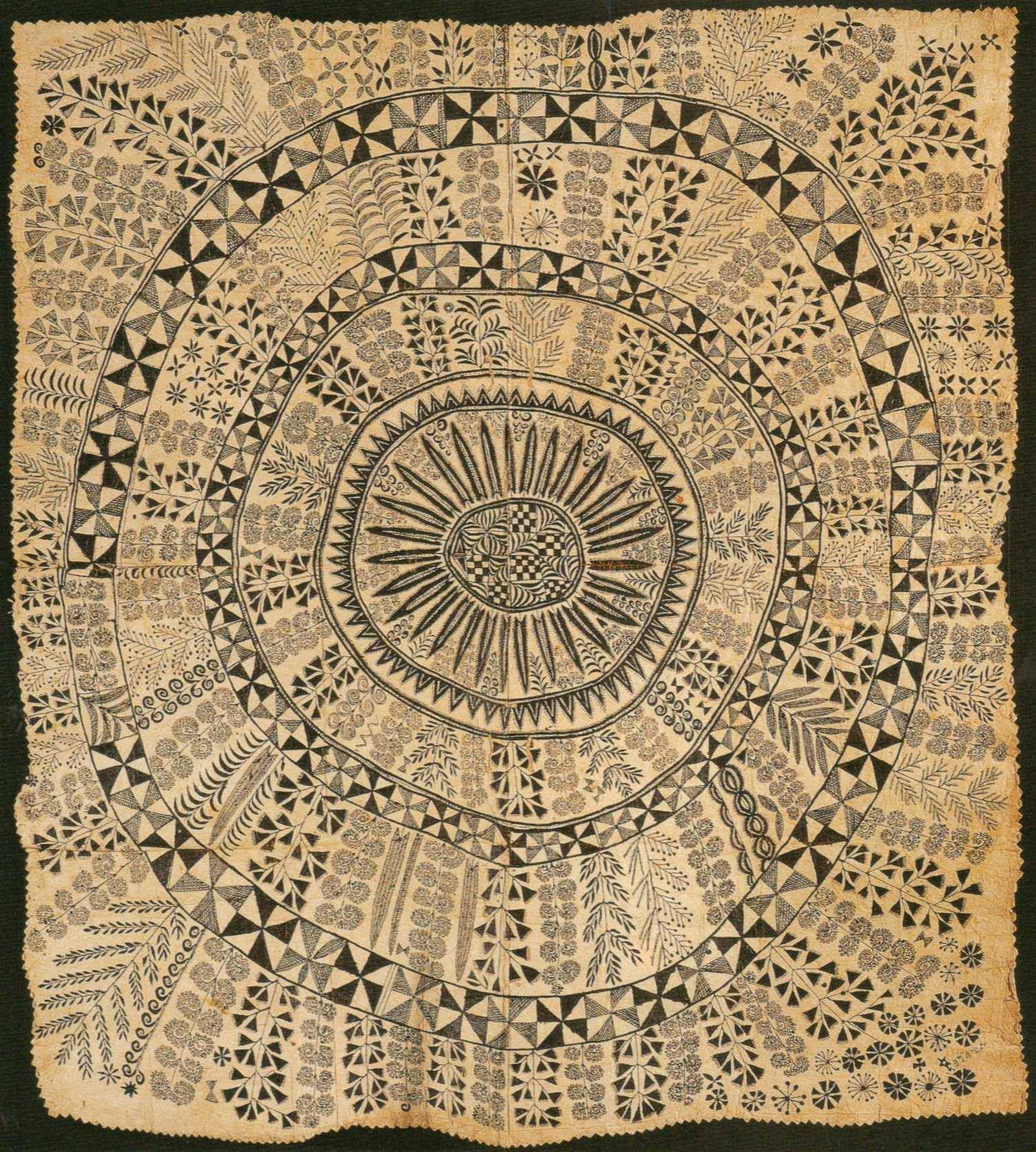

➼ Hiapo (Tapa)

Details

from Niue

c. 1850–1900

tapa or bark cloth, freehand painting

Found in Auckland War Memorial Museum, New Zealand

Technique

Tapa is cloth made from tree bark; the pieces are beaten and pasted together.

Using stencils, the artists dye the exposed parts of the tapa with paint.

After the tapa is dry, designs are sometimes repainted to enhance the effect.

Function: Traditionally worn as clothing before the importation of cotton.

Context

Hiapo is the word used in Niue for tapa (bark cloth).

Tapa takes on a special meaning: commemorating an event, honoring a chief, noting a series of ancestors.

Tapa is generally made by women.

Each set of designs is meant to be interpreted symbolically; many of the images have a rich history.

➼ Tamati Waka Nene

Details

By Gottfried Lindauer

1890

oil on canvas

Found in Auckland Art Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand

Subject

Subject is Tamati Waka Nene (c. 1780–1871), Maori chief and convert to the Wesleyan faith.

Painting is posthumous, based on a photograph by John Crombie.

Content

Emphasis is placed on symbols of rank: elaborate tattooing with Maori designs, staff with an eye in the center, feathers dangling from the staff.

Ceremonial weapon has a finely wrought blade with dangling feathers and abalone shell as a focal point or eye.

Status is revealed in oversize greenstone earring, which contains his power, or “mana,” and kiwi feather cloak.

Context

The painter was born in Bohemia and was famous for portraits of Maori chieftains upon his arrival in New Zealand in 1873–1874 until his death in 1926.

He was a journeyman painter and tradesman who worked on commission.

This is a European-style painting in its use of oil paint, canvas backing, coloring, modeling, shading, and atmospheric perspective.

Conflicting interpretations of works such as these:

Maori may see the portraits as an embodiment of the spirit of a person, and as a link between past and present.

Westerners may see the paintings as a commercial adventure with a monetary value.

Some may see the portrait as a record of a vanishing culture.

Others may interpret the work as anthropology highlighting aspects of Maori costuming and physiognomy, and what they could mean.

Still others may see the portraits as expressions of colonial dominance.

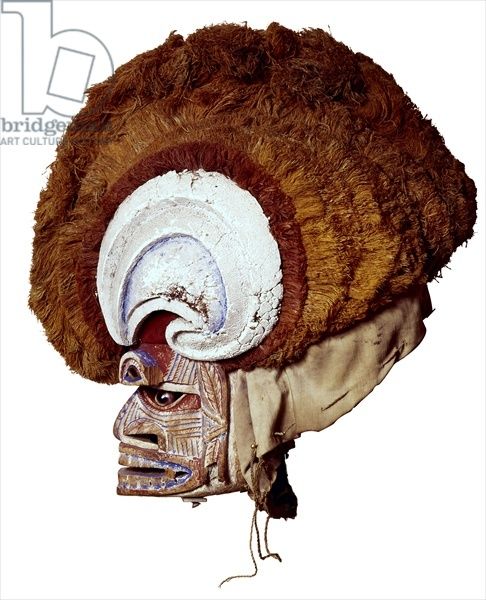

➼ Malagan Mask

Details

From New Ireland Province, Papua New Guinea

c. 20th century

wood, pigment, fiber, and shell

Found in Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas

Form

Masks are extremely intricate in their carving.

They are painted black, yellow, and red: important colors denoting violence, war, and magic.

Artists are specialists in using negative space.

Function

Sculptures of the deceased are commissioned; they represent the individual’s soul, or life force, not a physical presence.

The mask indicates the relationship of a particular deceased person to a clan and to living members of the family.

The large haircomb reflects a hairstyle of the time; masks are not physical portraits, only portraits of the soul.

Context

Malagan ceremonies send the souls of the deceased on their way to the otherworld.

Sometimes ceremonies begin months after death and last an extended period of time.

During the time after death the sponsors must organize the ceremonies and the feasts. They must also hire the sculptors who will carve the structures for the event.

An expensive undertaking: families often combine their wealth and honor several individuals.

The commissioned malagan sculptures are exhibited in temporary display houses. Each sculpture honors a specific individual and illustrates his or her relationships with ancestors, clan totems, and/or living family members.

During the course of the ceremony it is believed that the souls of the deceased enter the sculptures.

The ceremonies free the living from the obligation of serving the dead.

Structures are erected to suit a purpose; after the ceremony, the structures are considered useless and usually destroyed or allowed to rot—they have fulfilled their function.

➼ Buk (Mask)

Details

From Torres Strait

mid- to late 19th century

turtle shell, wood, fiber, feathers, and shell

Found in Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Form

Some masks combine human and animal forms; this mask shows a bird placed on top.

Turtle shell masks are unique to this region.

Function

The mask, like a helmet, is worn over the head.

Part of a larger grass costume used in ceremonies about death, fertility, or male initiation, perhaps even to ensure a good harvest.

Ceremonies involved fire, drum beats, and chanting; recreating mythical ancestral beings and their impact on these people in everyday activities.

Context

Torres Strait is the water passageway between Australia and New Guinea.

Human face may represent a cultural hero or ancestor.

➼ Presentation of Fijian mats and tapa cloths to Queen Elizabeth II during the 1953–1954 royal tour

Details

1953

multimedia performance, photographic documentation,

Found in Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

Materials

Costume, cosmetics including scent.

Chant; movement; pandanus fiber/hibiscus fiber mats.

Technique

Men oversee the growth of the mulberry trees that produce the tapa; women turn the bark into cloth.

Bark is removed from the tree, soaked in water, and treated to make it pliable.

Clubs are used to beat the strips into a long rectangular block to form pieces of cloth.

The edges of these smaller pieces are then glued or felted together to produce large sheets.

The tapa is decorated according to a local tradition; sometimes stenciled, sometimes printed or dyed.

Function: Enormous tapa clothes were made and presented to Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 in commemoration of her visit to Fiji on the occasion of her coronation as queen of England.

Context: The presentation to the queen is an example of performance art.

➼ Moai on Platform (Ahu)

Details

c. 1100–1600

volcanic tuff figures on basalt base

Found in Easter Island (Rapa Nui)

Form

Prominent foreheads; large broad noses; thin pouting lips; ears that reach to the top of their heads.

Short, thin arms fall straight down; hands on hips; hands across lower abdomen below navel.

Breasts and navels are delineated.

Backs are tattooed.

Topknots were added to some statues.

White coral was placed in the eyes to “open” them.

Function: Images represent personalities deified after death or commemorated as the first settler-kings.

Context

There are about 900 statues in all, 50 tons apiece, mostly male; almost all facing inland.

They were erected on large platforms, called ahu, of stone mixed with ashes from cremations; the platforms are as sacred as the statues that are on them.

After being carved, figures were said to have been “walked” into place from where they were quarried.

Beneath an ahu is a cemetery where village elders were buried.

The depletion of resources may have caused an ecological crisis which led to a decline in society and the destruction of the monuments.

Monuments were toppled face down because it was believed that the eyes had spiritual power.

Knowt

Knowt