Chapter 10: Serology Concepts

10.1: Serological Reagents

Immunogens and Antigens

Immunogen: A foreign substance that is capable of eliciting antibody formation when introduced into a host.

Natural immunogens are usually macromolecules such as proteins and polysaccharides.

Epitope: Also known as determinant site; the molecular structure of an immunogen, usually a small portion recognized by an antibody.

Multivalent: Multiple epitope in an immunogen.

Antigen: A foreign substance that is capable of reacting with an antibody.

Hapten: An example of a substance that is antigenic but not immunogenic. They are chemical compounds that are too small to elicit antibody production when they are introduced to a host animal.

Antibodies

Antibodies: Also known as immunoglobulins, are capable of binding specifically to antigens and are designated with an Ig prefix.

Isotypes: The immunoglobulins that differ based on the molecular variations in the constant domains of the heavy and light chains.

The five major classes of immunoglobulins are designated: IgG, IgA, IgM, IgD, and IgE.

IgD, IgE, and IgG are usually monomers.

IgM can be a membrane-bound monomer or a cross-linked pentamer.

IgA can be a monomer, dimer, or trimer.

Further exposure to the immunogen can elicit a secondary response, producing IgG, IgA, IgE, and IgD immunoglobulins.

IgG is the most abundant immunoglobulin in serum.

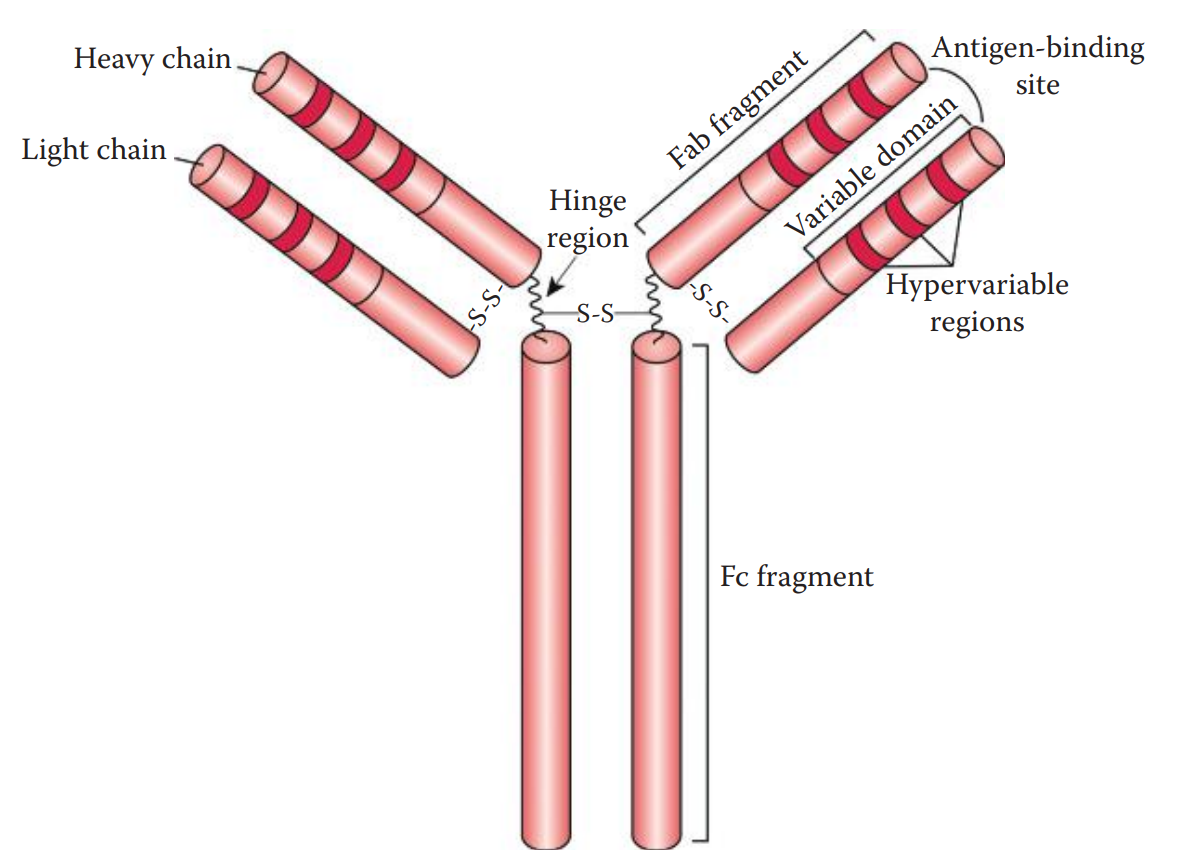

Immunoglobulins are composed of four polypeptide chains: two heavy (H) chains and two light (L) chains.

The H chain can be divided into fragment antigen-binding (Fab) and fragment crystallizable (Fc) fragments.

The L chain consists of a Fab fragment only.

A typical antibody has two identical antigen-binding sites and is thus considered bivalent.

At the amino acid sequence level, both H and L chains have variable and constant domains.

The variable domains are located at the N-terminal ends of the immunoglobulins.

Additionally, three small hypervariable regions are located within the variable domain of each chain.

Polyclonal Antibodies

To produce an antibody, an immunogen is usually introduced into a host animal.

A multivalent immunogen is capable of eliciting a mixture of antibodies with diverse specificities for the immunogen.

As a result, a polyclonal antibody is produced by different B lymphocyte clones in response to the different epitopes of the immunogen.

Humoral Antibodies: Circulating immunoglobulins.

The blood from an immune host is drawn and allowed to clot, resulting in the formation of a solid consisting largely of blood cells and a liquid portion known as serum containing antibodies.

Polyclonal Antiserum: Preparation of humoral antibodies.

Monoclonal Antibodies

To produce a monoclonal antibody, spleen cells are harvested from a host animal, such as a mouse, inoculated with an immunogen.

Next, the plasma cells of the spleen, which produce antibodies, are fused with myeloma cells.

The fused cells, called hybridoma cells, are immortal in cell cultures.

Pools of hybridoma cells are diluted into single clones and are allowed to proliferate. The clones are then screened for the specific antibody of interest.

Monoclonal antibodies have been utilized in many serological assays. However, it react with only a single epitope of a multivalent antigen and, therefore, cannot form cross-linked networks in precipitation assays.

Antiglobulins

If a purified foreign immunoglobulin or a fragment of a foreign immunoglobulin is introduced into a host, the antibodies produced are known as antiglobulins.

Antiglobulins that are specific to a particular isotype can be produced in laboratories.

It is possible to produce nonspecific antiglobulins, which recognize an epitope that is common to all isotypes of an immunoglobulin class.

They are important reagents in many serological tests.

10.2: Strength of Antigen-Antibody Binding

The binding of an antigen to its specific antibody is mediated by the interaction between the epitope of an antigen and the binding site of its antibody.

Noncovalent bonds can be formed during antigen–antibody binding.

Affinity: The energy of the interaction of a single epitope on an antigen and a single binding site on a corresponding antibody.

Cross-reaction: Antibodies bind with a lower strength to antigens that are structurally similar to the immunogen.

Avidity: The overall strength of the binding of an antibody and an antigen.

It reflects the combined synergistic strength of the binding of all the binding sites of antigens and antibodies rather than the sum of individual affinities.

It also reflects the overall stability of an antigen–antibody complex that is essential for many serological assays.

10.3: Antigen-Antibody Binding Reactions

Primary Reactions

It is the binding of a single epitope of an antigen (Ag) and a single binding site of an antibody (Ab) to form an antigen–antibody complex.

Secondary Reactions

Precipitation

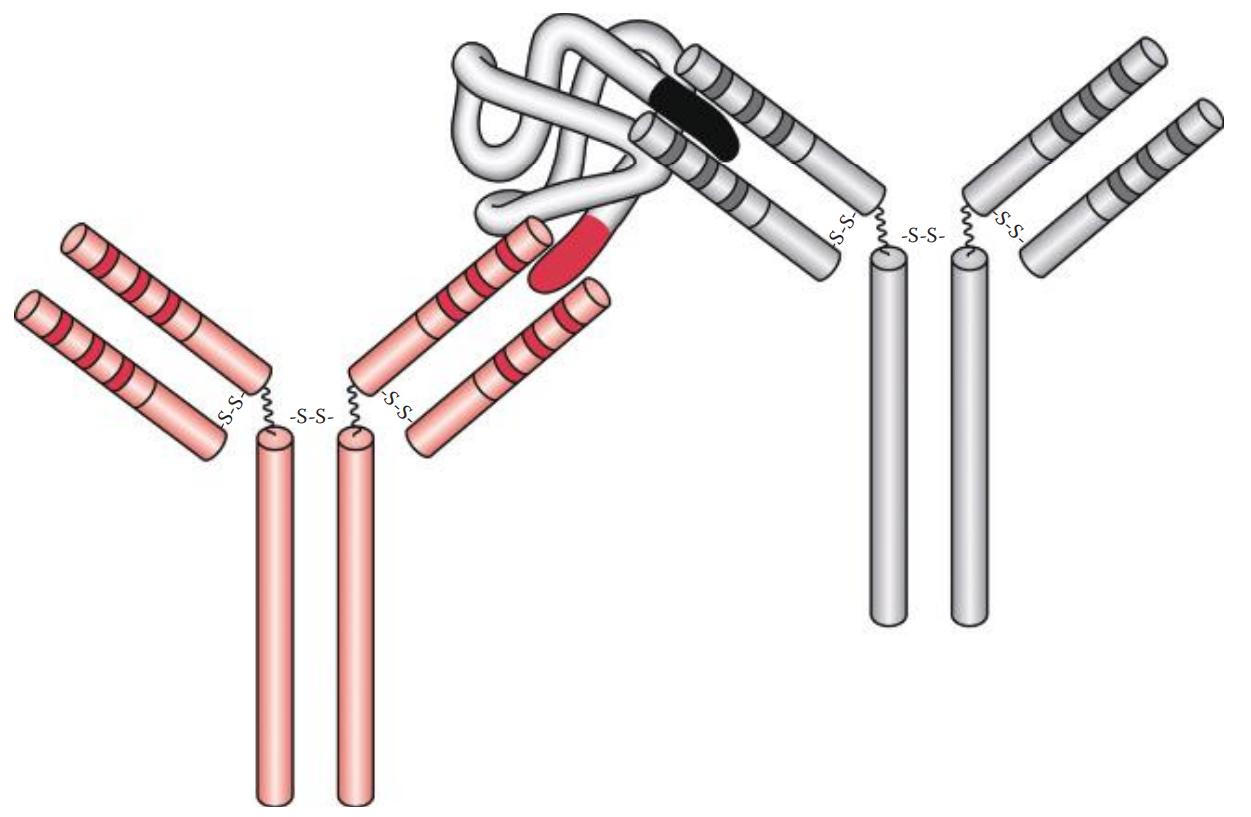

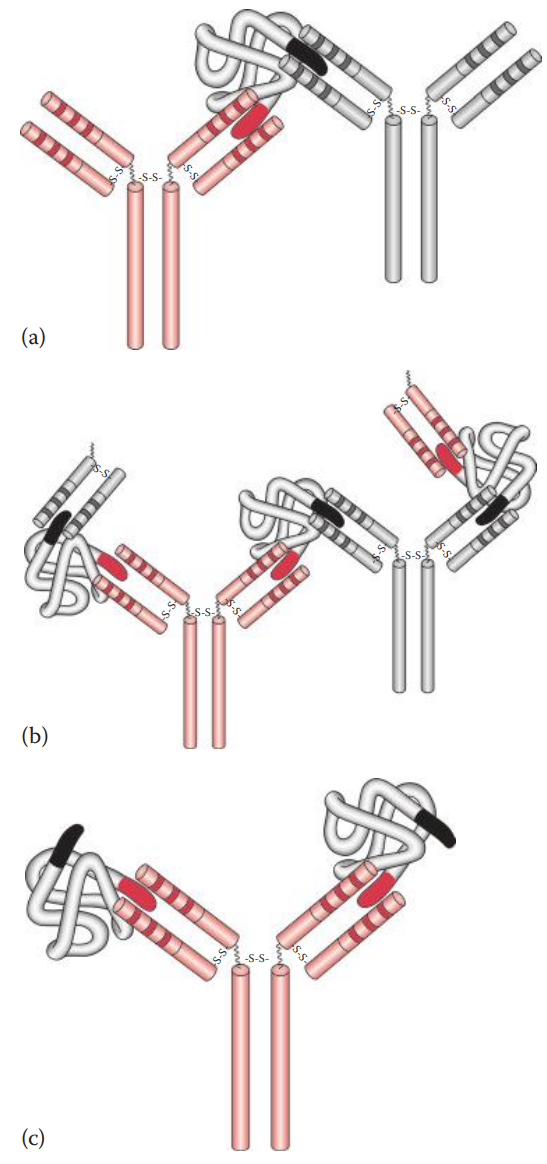

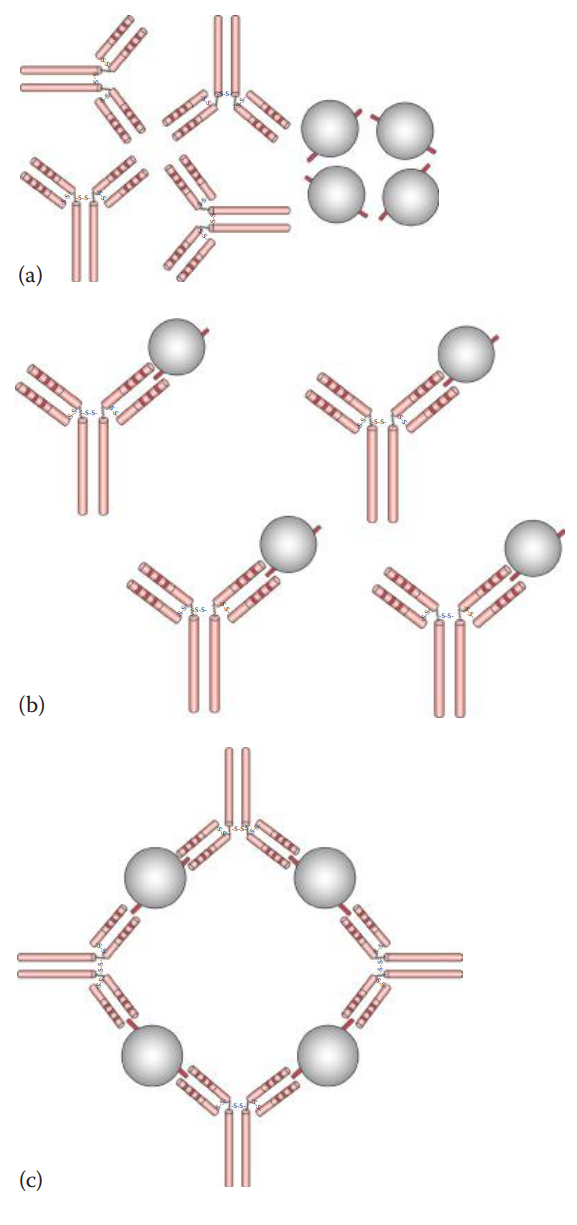

If a soluble antigen is mixed and incubated with its antibody, the antigen–antibody complexes can form cross-linked complexes at the optimal ratio of antigen-to-antibody concentration.

Precipitins: Antibodies that produce such precipitation.

If an increasing amount of soluble antigen is mixed with a constant amount of antibody, the amount of precipitate formed can be plotted.

Precipitin Curve: Illustrates the results observed when antigens and antibodies are mixed in various concentration ratios. It has three zones:

Prozone: Here the ratio of antigen–antibody concentration is low.

The Zone of Equivalence: As the concentrations of antigen increase, the amount of precipitate increases until it reaches a maximum.

Post zone: Here the ratio of antigen–antibody concentrations is high or in excess.

Agglutination

If the antigens are located on the surfaces of cells or carriers antibodies can bind to the surface antigens and can form cross-links among cells or carriers, causing them to aggregate.

If the antigen is located on an erythrocyte, the agglutination reaction is designated hemagglutination.

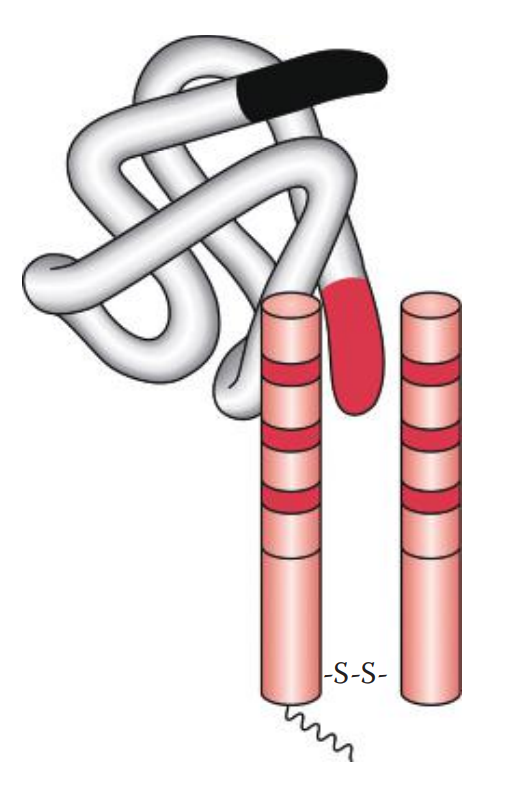

Initial Binding: The first step of the reaction involves antigen–antibody binding at a single epitope on the cell surface.

Lattice Formation: The second step involves the formation of a cross-linked network resulting in visible aggregates that constitute a lattice.

Agglutinins: Antibodies that produce agglutination.

Complete Antibody: Capable of carrying out both primary and secondary interactions that result in agglutination.

Incomplete Antibody: An antibody that can carry out initial binding but fails to form agglutination.

Knowt

Knowt