CH. 10: Analgesic

Analgesic Drugs

OBJECTIVES

When you reach the end of this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

Define acute pain and chronic pain.

Contrast the signs, symptoms, and management of acute and chronic pain.

Discuss the pathophysiology and characteristics associated with cancer pain and other special pain situations.

Describe pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches for the management of acute and chronic pain.

Discuss the use of nonopioids, NSAIDs, opioids (opioid agonists, mixed action opioids, agonists-antagonists, and antagonists), and miscellaneous drugs in pain management, including acute and chronic pain, cancer pain, and special pain situations.

Identify examples of drugs classified as nonopioids, NSAIDs, opioids, and miscellaneous drugs.

Briefly describe the mechanism of action, indications, dosages, routes of administration, adverse effects, toxicity, cautions, contraindications, and drug interactions of various analgesics.

Contrast the pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic management of acute and chronic pain with the management of cancer pain and pain in terminal conditions.

Briefly describe the specific standards of pain management as defined by the WHO and The Joint Commission.

Develop a nursing care plan based on the nursing process related to the use of nonopioid and opioid drug therapy for patients in pain.

Identify various resources, agencies, and professional groups involved in establishing standards for pain management and promotion of a holistic approach to patient care.

KEY TERMS

Acute pain: Sudden onset pain, subsides when treated, lasting less than 6 weeks.

Addiction: Chronic disease influenced by genetic, psychosocial, and environmental factors.

Adjuvant analgesic drugs: Added for combined therapy, may have independent analgesic properties.

Agonist: Binds to a receptor and causes a response.

Agonists-antagonists: Bind to a receptor and cause a partial response.

Analgesic ceiling effect: Maximum effectiveness reached; higher doses do not increase pain relief.

Analgesics: Medications that relieve pain without causing loss of consciousness.

Antagonist: Binds to a receptor and blocks a response.

Breakthrough pain: Pain occurring between doses of medication.

Cancer pain: Pain related to cancer or its metastasis.

Chronic pain: Lasting longer than 3 to 6 months or persists after injury healing.

Neuropathic pain: Caused by dysfunction of a nerve.

Nociception: Processing of pain signals in the brain.

DRUG PROFILES

Acetaminophen, Codeine sulfate, Fentanyl, Hydromorphone, Lidocaine, Methadone, Morphine, Naloxone, Oxycodone, Tramadol.

NONPHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR PAIN

Acupressure, Acupuncture, Art therapy, Behavioral therapy, Biofeedback, Comfort measures, Distraction, Hot/Cold packs, Hypnosis, Imagery, Massage, Meditation, Music therapy, Physical therapy, Relaxation, Yoga, and more.

HIGH-ALERT DRUGS

Codeine sulfate, Fentanyl, Hydromorphone, Meperidine, Methadone, Morphine, Oxycodone, Tramadol.

Overview

The management of pain is a very important aspect of nursing care. Pain is one of the most common reasons that patients seek health care. Surgical and diagnostic procedures often require pain management, as do several diseases, including arthritis, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, cancer, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Pain leads to much suffering and is a tremendous economic burden in terms of lost workplace productivity, workers’ compensation payments, and other related health care costs.

To provide high-quality patient care, the nurse must be well informed about both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic methods of pain management. This chapter focuses on pharmacologic methods of pain management. Nonpharmacologic methods are listed in Box 10.1.

Medications that relieve pain without causing loss of consciousness are classified as analgesics. There are various classes of analgesics, determined by their chemical structures and mechanisms of action. This chapter focuses primarily on the opioid analgesics, which are used to manage moderate to severe pain. Often drugs from other chemical categories are added to the opioid regimen as adjuvant analgesic drugs (or adjuvants).

Pain is most commonly defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with either actual or potential tissue damage. It is a very personal and individual experience. Pain can be defined as whatever the patient says it is, and it exists whenever the patient says it does. Although the mechanisms of pain are becoming better understood, a patient’s perception of pain is a complex process involving physical, psychological, and even cultural factors.

Patient-Centered Care: Cultural Implications

The Patient Experiencing Pain: Each culture has its own beliefs, thoughts, and ways of approaching, defining, and managing pain. Attitudes, meanings, and perceptions of pain vary with culture, race, and ethnicity.

African Americans believe in the power of healers who rely strongly on religious faith and often use prayer and laying on of hands for pain relief.

Hispanic Americans believe in prayer, the wearing of amulets, and the use of herbs and spices, often including religious practices, massage, and cleansings.

Chinese traditional methods include acupuncture, herbal remedies, and cold treatments.

Asian and Pacific Islander patients may be reluctant to express pain, believing it is God’s will or punishment for past sins.

Native Americans often use massage, heat application, sweat baths, herbal remedies, and seek harmony with nature for pain relief.

Arab culture expects patients to express pain openly and anticipate immediate relief through injections or intravenous drugs.

It is crucial to remain aware of all cultural influences on health-related behaviors, patients’ attitudes toward medication therapy, and thus, ultimately, its effectiveness. A thorough assessment that includes questions about the patient’s cultural background and practices is important for effective and individualized nursing care.

There is no single approach to effective pain management. Instead, it is tailored to each patient’s needs, taking into account the cause of the pain, any concurrent medical conditions, characteristics of the pain, and the psychological and cultural characteristics of the patient. Adequate pain management requires ongoing reassessment of the pain and the effectiveness of treatment. The patient’s emotional response to pain depends on their psychological experiences of pain. Pain results from the stimulation of sensory nerve fibers known as nociceptors, which transmit pain signals to the spinal cord and brain, leading to the sensation of pain, or nociception.

Pain Impulses and Sensitivity

The physical impulses that signal pain activate various nerve pathways from the periphery to the spinal cord and to the brain. The level of stimulus needed to produce a painful sensation is referred to as the pain threshold. This threshold is similar for most individuals as it measures the physiologic response of the nervous system; however, variations in pain sensitivity may result from genetic factors.

There are three main receptors thought to be involved in pain:

Mu receptors: Located in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, they play the most crucial role in pain perception.

Kappa receptors: Less important but still involved in pain sensations.

Delta receptors: Also play a role in the perception of pain.

Pain receptors are found in both the central nervous system (CNS) and various body tissues. Pain perception is closely linked to the number of mu receptors, which is controlled by the mu opioid receptor gene. When the number of mu receptors is high, pain sensitivity is diminished. Conversely, when the receptors are reduced or absent, relatively minor noxious stimuli may be perceived as painful.

The patient’s emotional response to pain is influenced by several factors, including age, sex, culture, previous pain experience, and anxiety level. While pain threshold is the physiologic aspect of pain, the psychological component is known as pain tolerance. Pain tolerance refers to the amount of pain a patient can endure without it interfering with normal functioning.

Unlike pain threshold, pain tolerance is a subjective response that can vary among individuals and is modulated by personality, attitude, environment, culture, and ethnic background. Pain tolerance can even vary within the same individual based on specific circumstances.

Table 10.1: Conditions that Can Alter Pain Tolerance

(Include specific conditions that may be detailed in the original text or elsewhere.)

TABLE 10.1

Conditions That Alter Pain TolerancePain ThresholdLowered: Anger, anxiety, depression, discomfort, fear, isolation, chronic pain, sleeplessness, tirednessRaised: Diversion, empathy, rest, sympathy, medications (analgesics, antianxiety drugs, antidepressants)

TABLE 10.2

Acute Versus Chronic Pain

Type of Pain | Onset | Duration | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

Acute | Sudden (minutes to hours); usually sharp, localized; physiologic response (SNS: tachycardia, sweating, pallor, increased blood pressure) | Limited (has an end) | Myocardial infarction, appendicitis, dental procedures, kidney stones, surgical procedures |

Chronic | Slow (days to months); long duration; dull, persistent aching | Persistent or recurring (endless) | Arthritis, cancer, lower back pain, peripheral neuropathy |

Types of Pain According to Source

Somatic pain: originates from skeletal muscles, ligaments, and joints.

Visceral pain: originates from organs and smooth muscles.

Superficial pain: originates from the skin and mucous membranes.

Deep pain: occurs in tissues below skin level.

Pain Subclassification

Neuropathic pain: Results from damage to peripheral or CNS nerve fibers.

Phantom pain: Sensations in an area that has been surgically or traumatically removed.

Cancer pain: Can be acute or chronic, often due to pressure on nerves, organs, or tissues.

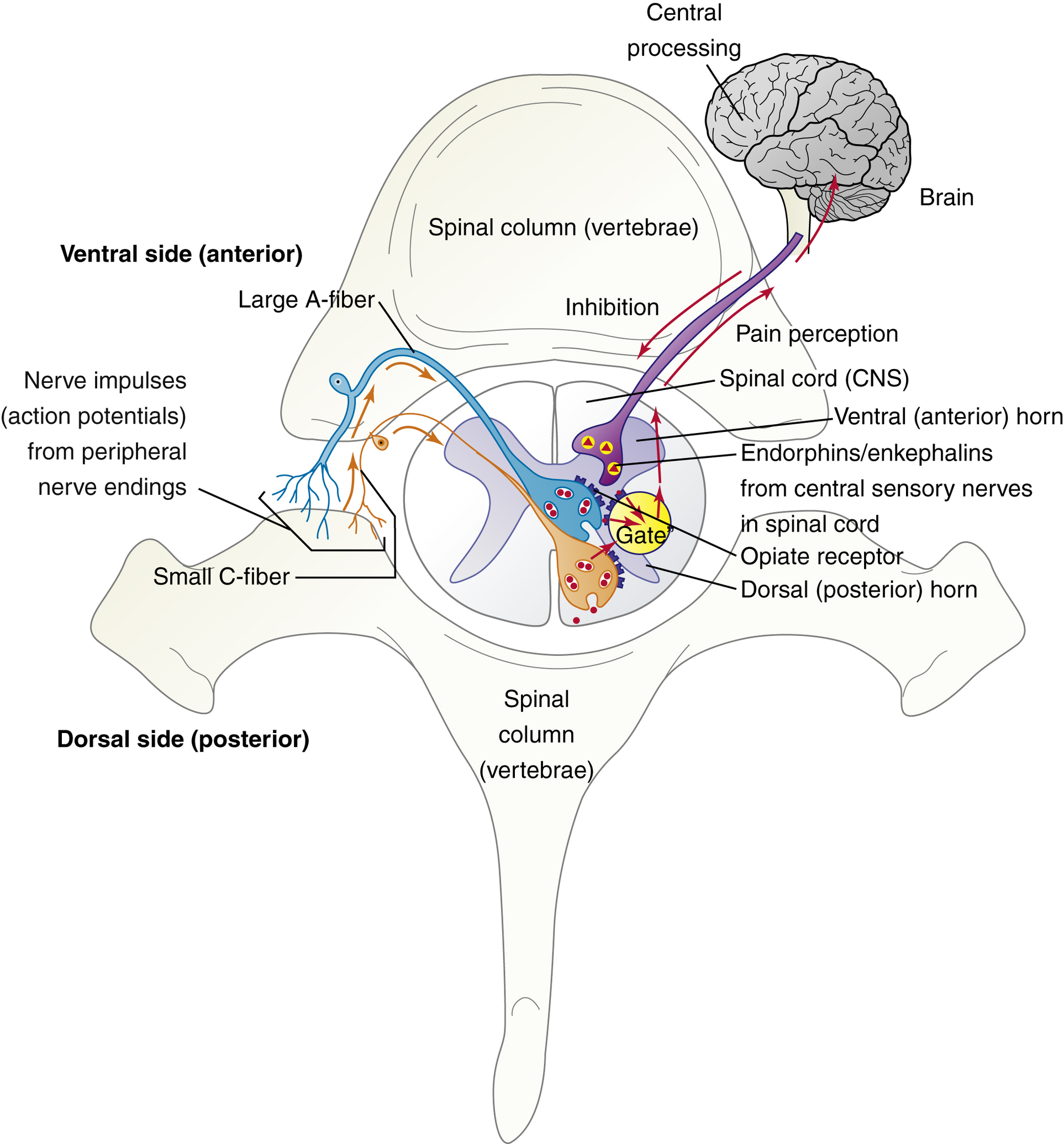

Gate Control Theory

Proposed by Melzack and Wall in 1965; suggests that tissue injury releases chemicals that affect pain perceptions through nerve pathways.

Nociceptors: Pain receptors that transmit signals to the CNS.

A fibers: Inhibit pain transmission; C fibers: Facilitate pain transmission.

Endogenous Pain Relievers

Enkephalins and Endorphins: Natural painkillers produced in the body that inhibit pain through opioid receptor interaction and gate modulation.

TABLE 10.3

A and C Nerve Fibers

Type of Fiber | Myelin Sheath | Fiber Size | Conduction Speed | Type of Pain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

A | Yes | Large | Fast | Sharp and well localized |

C | No | Small | Slow | Dull and nonlocalized |

Treatment of Pain in Special Situations

It is estimated that one of every three Americans experiences ongoing pain, which is poorly understood and often undertreated. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) allows patients to self-medicate by pressing a button on a PCA infusion pump. Commonly used medications include morphine and hydromorphone. However, hazards of PCA include familial misuse known as PCA by proxy, leading to potential overdoses.

Complex pain syndromes benefit from a multimodal approach involving both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments. In cancer patients, comfort is prioritized over concerns of drug addiction. Opioid tolerance may develop, necessitating higher doses over time, but psychologic dependence is rare. Dosing routes favored include oral, intravenous, subcutaneous, transdermal, and rectal rather than intramuscular injections.

Moreover, treating acute pain in opioid-dependent patients should involve maintaining their chronic medication along with an additional 20% to 40% for acute discomfort. Extended-release opioids are preferred over immediate-release formulations to minimize the risk of reinforcing addictive behaviors. Genetic variations may affect drug efficacy, requiring personalized approaches to pain management.

Evidence-Based Practice

Research indicates substantial knowledge deficits among nursing students and faculty regarding pain management, prompting the need for improved educational frameworks in nursing curricula. A study highlighted that pain assessment was better understood than the guidelines for pain medication management. Therefore, ongoing education in pain assessment, pharmacotherapeutics, and nonpharmacologic interventions is essential for nursing professionals to improve care outcomes.

Breakthrough Pain Management

Breakthrough pain often arises in patients on long-acting opioids as analgesic effects wane. Immediate-release formulations should be used for 'prn' needs between scheduled doses, but caution against manipulating extended-release options is crucial due to risks of overdose. Ongoing FDA initiatives promote abuse-deterrent formulations of opioids. Adjuvant drugs like NSAIDs, antidepressants, and corticosteroids may complement treatment, allowing for effective pain relief while minimizing opioid dosages and side effects.

Safety and Quality Improvement

Identifying Potential Opioid Adverse Effects

ConstipationOpioids decrease gastrointestinal (GI) tract peristalsis due to central nervous system (CNS) depression, leading to constipation as a common adverse effect. Stool becomes excessively dehydrated due to prolonged retention in the GI tract.Preventive measures:

Increase fluid intake

Use stool softeners (e.g., docusate sodium)

Stimulants (e.g., bisacodyl or senna)

Lactulose, sorbitol, and polyethylene glycol (MiraLAX) have proven effectiveness.

Bulk-forming laxatives, like psyllium, may also be used with adequate fluid intake to prevent fecal impactions or bowel obstructions.

Nausea and VomitingSome opioids can decrease GI tract peristalsis and stimulate the CNS vomiting center, causing nausea and vomiting.Preventive measures:

Manage with antiemetics such as phenothiazines.

Sedation and Mental CloudingAny change in mental status should be evaluated to rule out causes other than CNS depression related to drugs. Excessive sedation is closely associated with respiratory depression.Preventive measures:

Implement safety precautions.

Decrease opioid dosage or change the drug if persistent sedation occurs.

Consider CNS stimulants as ordered.

Respiratory DepressionLong-term opioid use may lead to tolerance to respiratory depression.Preventive measures:

Naloxone may be required for severe respiratory depression.

Subacute OverdoseSubacute overdose can develop slowly over hours to days, characterized by somnolence and respiratory depression.Preventive measures:

Hold one or two doses of the opioid analgesic to assess improvement in mental and respiratory depression. If improvement is noted, reduce the opioid dosage by 25%.

Other Opioid Adverse EffectsLess common adverse effects include dry mouth, urinary retention, pruritus, dysphoria, euphoria, sleep disturbances, and sexual dysfunction.Preventive measures:

Ongoing assessment for adverse effects allows implementation of appropriate measures (e.g., sugar-free hard candy or artificial saliva for dry mouth; diphenhydramine for pruritus).

TABLE 10.4

Chemical Classification of Opioids

Chemical Category | Opioid Drugs |

|---|---|

Meperidine-like drugs | meperidine, fentanyl, remifentanil, sufentanil, alfentanil |

Methadone-like drugs | methadone |

Morphine-like drugs | morphine, heroin, hydromorphone, codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone |

Other | tramadol, tapentadol |

Adjuvant drugs are commonly used in the treatment of neuropathic pain, where opioids may not be completely effective. Neuropathic pain typically results from nerve damage due to diseases such as diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia (after shingles), AIDS, or injuries, including those from surgical procedures (e.g., post-thoracotomy pain syndrome after cardiothoracic surgery). Common symptoms include hypersensitivity or hyperalgesia to mild stimuli (known as allodynia), such as light touch, pinprick sensations, or bed sheets on the feet. Patients may also experience hyperalgesia to painful stimuli, as with pressure from an inflated blood pressure cuff. Sensations may vary from heat, cold, numbness, tingling, burning, to electrical feelings. Common adjuvants for treatment include the antidepressant amitriptyline and anticonvulsants like gabapentin and pregabalin.

The WHO's three-step analgesic ladder serves as a pain management standard:

Step 1: Nonopioids (with or without adjuvant medications) are used following pain assessment.

Step 2: If pain persists or worsens, opioids are introduced with or without nonopioids and/or adjuvants.

Step 3: For moderate to severe pain, stronger opioids are administered, alongside nonopioids and/or adjuvants as necessary. Not all patients may respond effectively to this method, and some may require a specialist in pain management.

Pharmacology Overview

The terms opioids and narcotics are often used interchangeably. However, the appropriate term when discussing pharmacology is opioid, while law enforcement professionals commonly use the term narcotics.

Opioids are classified as:

Mild agonists: (e.g., codeine, hydrocodone)

Strong agonists: (e.g., morphine, hydromorphone, oxycodone, meperidine, fentanyl, and methadone)

Meperidine is not recommended for long-term use due to the accumulation of its neurotoxic metabolite, normeperidine, which can cause seizures. In 2010, the mild agonist propoxyphene (Darvocet) was withdrawn from the market because of adverse effects.

Opiate agonists-antagonists (e.g., pentazocine, nalbuphine) exhibit an analgesic ceiling effect, indicating a maximum analgesic effect where increased dosages do not improve pain relief. These drugs are primarily useful for patients who have not been previously exposed to opioids.

There is a noticeable trend away from intramuscular injections due to associated bruising, bleeding risks, and discomfort, with a preference for intravenous, oral, and transdermal routes of administration.

Opioid Drugs

The pain-relieving drugs known as opioid analgesics originate from the opium poppy plant. The term opium is derived from the Greek word meaning "juice." More than 20 different alkaloids can be obtained from the unripe seeds of the poppy.

Chemical Structure

Opioid analgesics are very strong pain relievers, classified based on chemical structure or action at receptors. Of the 20 alkaloids from the opium poppy, only 3 are clinically useful: morphine, codeine, and papaverine, the latter being a smooth muscle relaxant. Morphine and codeine are the pain relievers, while relatively simple synthetic modifications yield three chemical classes of opioids: morphine-like, meperidine-like, and methadone-like drugs. Understanding these structures can help in cases of allergic reactions; for instance, fentanyl can be used if a patient has an anaphylaxis reaction to morphine.

Mechanism of Action and Drug Effects

Opioid analgesics are characterized by their mechanism of action: agonists, agonists-antagonists, and antagonists (nonanalgesic). An agonist binds to opioid pain receptors in the brain, triggering analgesic effects. Agonists-antagonists bind but produce a weaker pain response, useful in obstetric patients to prevent oversedation. Antagonists bind to receptors without reducing pain signals and reverse the effects of agonists.

Opioid Receptors and Their Characteristics

Receptor Type: muPrototypical Agonist: morphineEffects of Opioid Stimulation: supraspinal analgesia, respiratory depression, euphoria, sedation

Receptor Type: kappaPrototypical Agonist: ketocyclazocineEffects of Opioid Stimulation: spinal analgesia, sedation, miosis

Receptor Type: deltaPrototypical Agonist: EnkephalinsEffects of Opioid Stimulation: analgesia

The mu receptor is the most important and responsive to opioids, affecting sedation, potency, and hallucination likelihood. Understanding relative potency aids in clinical settings through the concept of equianalgesia, which calculates equivalent analgesic doses across different opioids. For instance, hydromorphone (Dilaudid) is seven times more potent than morphine, significantly impacting patient safety and dosage administration.

IndicationsThe main use of opioids is to alleviate moderate to severe pain. The effectiveness of pain control or occurrence of unwanted adverse effects largely depends on the specific drug, its receptor interactions, and its chemical structure.

Strong opioid analgesics such as fentanyl, sufentanil, and alfentanil are commonly used with anesthetics during surgery. Fentanyl injection is particularly popular for managing postoperative and procedural pain due to its rapid onset and short duration.

Transdermal fentanyl patches are designed for long-term pain management and should not be used for postoperative or short-term pain control.

Morphine, hydromorphone, and oxycodone are frequently used for controlling postoperative pain. Morphine and hydromorphone are available in injectable forms, making them first-line analgesics in the immediate postoperative setting.

The use of meperidine is declining due to its higher risk of toxicity.

All oxycodone formulations are administered orally, with OxyContin being a sustained-release form designed for up to 12 hours of pain relief.

MS Contin is a long-acting form of morphine sulfate. These extended-release formulations have prolonged duration and should not be crushed.

In 2013, the FDA approved a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) for long-acting opioids, requiring prescriber and patient education to reduce misuse and deaths related to prescription opioids.

Recent black box warnings on all opioids indicate risks for misuse, abuse, and potential addiction, which can lead to death.

EQUIANALGESIC DOSES

Oral Dose (mg) | Parenteral Dose (mg) | Oral-to-Parenteral Dose Ratio | Dosing Interval (hr) |

|---|---|---|---|

Morphine | 30 | 10 | 3:1 |

Hydromorphone | 7.5 | 1.5 | 5:1 |

Oxycodone | 15 | N/A | 4 (immediate release) |

Hydrocodone | 30 | N/A | 6 |

Example: A patient with colon cancer requiring conversion from oral oxycodone to intravenous morphine due to a bowel obstruction may need dosage calculations based on provided conversion ratios.

Contraindications

Contraindications to the use of opioid analgesics include known drug allergy and severe asthma. It is common for patients to state they are allergic to codeine; however, in many cases, the adverse reaction is nausea rather than a true allergy. Similarly, patients may claim to be allergic to morphine due to itching, which results from histamine release and not an allergic reaction. It is crucial to ascertain the exact nature of a patient’s stated allergy.Although not absolute contraindications, extreme caution is advised in the following conditions:

Respiratory insufficiency, especially when resuscitative equipment is unavailable.

Elevated intracranial pressure (e.g., severe head injury).

Morbid obesity and/or sleep apnea.

Myasthenia gravis.

Paralytic ileus (bowel paralysis).

Pregnancy, particularly with long-term use or high dosages.

Adverse Effects

Many unwanted effects of opioid analgesics are associated with their pharmacologic effects beyond the CNS. These effects include:

Histamine Release: Opioids can cause histamine release, leading to effects like itching, rash, and hemodynamic changes (e.g., flushing and orthostatic hypotension). The extent of histamine release varies by the drug's chemical class, with naturally occurring opiates (e.g., morphine) causing more release than synthetic opioids (e.g., meperidine).

Opioids also exhibit a strong potential for abuse, especially those with high affinity for mu receptors, which can produce significant euphoria and psychological dependence. The FDA mandates black box warnings for all immediate-release and long-acting opioids concerning the risks of misuse, abuse, and addiction.

Safety and Quality Improvement: Preventing Medication Errors with Transdermal Fentanyl Patches

Transdermal fentanyl patches should only be used by patients who are opioid-tolerant.

To be opioid tolerant, a patient must have taken certain opioids for a week or longer: morphine 60 mg daily, oral oxycodone 30 mg daily, or 8 mg of oral hydromorphone daily.

Prescribers knowledgeable in potent opioids should prescribe transdermal fentanyl.

Previous extended-release opioids must be tapered or discontinued before starting transdermal fentanyl.

The dosing regimen must be tailored to the patient's previous analgesic treatments and risk factors.

Patients must be monitored closely for respiratory depression, especially within the first 24 to 72 hours of initiation.

Heat must never be applied over a fentanyl patch due to increased absorption risks.

Proper disposal techniques should be taught to prevent accidental exposure, especially to children.

All medications, including patches, must be kept away from children and pets.

Following proper disposal guidelines, such as flushing used patches, helps prevent accidental exposure.

Patient education is critical for safety and understanding of opioid use and potential risks.

Note: It is important to educate patients on the risks of opioid analgesics and ensure proper use and disposal to mitigate potential adverse effects and complications.

TABLE 10.6

Opioid-Induced Adverse Effects by Body System

Body System | Adverse Effects |

|---|---|

Cardiovascular | Hypotension, flushing, bradycardia |

Central nervous | Sedation, disorientation, euphoria, lightheadedness, dysphoria |

Gastrointestinal | Nausea, vomiting, constipation, biliary tract spasm |

Genitourinary | Urinary retention |

Integumentary | Itching, rash, wheal formation |

Respiratory | Respiratory depression and possible aggravation of asthma |

The most serious adverse effect of opioid use is CNS depression, which may lead to respiratory depression. When death occurs from opioid overdose, it is almost always because of respiratory depression. Care must be taken to titrate the dose so that the patient’s pain is controlled without affecting respiratory function. Individual responses to opioids vary, and patients may occasionally experience respiratory compromise despite careful dose titration. Respiratory depression can be prevented by using drugs with very short duration of action and no active metabolites. It is more common in patients with a preexisting condition causing respiratory compromise, such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or sleep apnea. Respiratory depression is strongly related to the degree of sedation.

GI tract adverse effects are common because of stimulation of GI opioid receptors. Nausea, vomiting, and constipation are the most common adverse effects. Opioids can irritate the GI tract, stimulating the chemoreceptor trigger zone in the CNS, causing nausea and vomiting. They slow peristalsis and increase absorption of water from intestinal contents, leading to constipation. This is more pronounced in hospitalized patients who are nonambulatory. Patients may require laxatives to help maintain normal bowel movements. Specific drugs for opioid-induced constipation include naloxegol (Movantik), methylnaltrexone (Relistor), naldemedine (Symproic), lubiprostone (Amitiza), and alvimopan (Entereg), usually for chronic opioid users. Urinary retention is also an unwanted effect due to increased bladder tone. Severe hypersensitivity or anaphylactic reactions to opioids are rare. Many patients may experience GI discomforts or histamine-mediated reactions and incorrectly label these as “allergic reactions.” True anaphylaxis is rare, even with intravenous opioids. Patients may complain of flushing, itching, or wheal formation at the injection site, but this is typically local and histamine mediated, not a true allergy.

Toxicity and Management of Overdose

Naloxone and Naltrexone:

Naloxone and naltrexone are opioid antagonists that competitively bind to all opioid receptor sites (mu, kappa, delta).

Naloxone is primarily used for the management of opioid overdose, effectively reversing respiratory depression caused by opioids.

Naltrexone is utilized for treating alcohol and opioid addiction.

Physical Dependence and Withdrawal:

Opioid-tolerant patients typically experience some degree of physical dependence. Withdrawal symptoms may occur when an opioid is abruptly discontinued or when an opioid antagonist is administered, leading to abstinence syndrome.

Gradual dosage reduction after chronic opioid use is advisable to minimize withdrawal severity.

Respiratory Depression:

The most serious adverse effect of opioids is respiratory depression. Mild hypoventilation may sometimes be reversed by stimulating the patient.

If not effective, ventilatory support (e.g., bag and mask, endotracheal intubation) and opioid antagonists (i.e., naloxone) may be necessary.

Since naloxone's effects are short-lived (approximately 1 hour), repeated dosing may be required, especially with long-acting opioids.

Withdrawal Onset:

The onset of withdrawal symptoms correlates with the half-life of the opioid used:

Short-acting opioids result in withdrawal symptoms within 6 to 12 hours, peaking at 24 to 72 hours.

Long-acting opioids may take 24 hours or longer for symptoms to appear and usually result in milder withdrawal.

Interactions:

Significant drug interactions exist with opioids, particularly when combined with alcohol, antihistamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, phenothiazines, and other CNS depressants, leading to additive respiratory depression.

Co-administration of opioids and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (e.g., selegiline) can lead to severe adverse effects, including respiratory depression and hypotension.

The FDA has issued black box warnings for the combined use of opioids and benzodiazepines due to the risks of respiratory depression, coma, and death.

Laboratory Test Interactions:

Opioid use may cause abnormal increases in serum levels of various enzymes (e.g., amylase, alanine aminotransferase) and substances, and also produce alterations in urinary test results (i.e., decreased 17-ketosteroids).

Safety: Laboratory Values Related to Drug Therapy

Laboratory Test | Normal Ranges | Rationale for Assessment |

|---|---|---|

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) | 30–120 units/L | ALP is primarily found in the liver, biliary tract, and bone. It's important for identifying liver and bone disorders, with increased levels indicating obstructive biliary disease and cirrhosis. |

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) | 4–36 units/L | ALT is mainly found in the liver. Elevated levels may reflect liver injury or disease, affecting drug metabolism and potentially leading to toxic drug levels. |

Gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) | Male/female 45 years and older: 8–38 units/L | Elevated GGT can indicate liver cell damage and is influenced by race, with higher normal values in individuals of African ancestry. |

Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) | 0–35 units/L | Elevated AST levels indicate hepatocellular disease due to injury that leads to cell lysis, detectable in the bloodstream. |

Lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) | 100–190 units/L | LDH is present in multiple tissues, and elevated levels signal cell damage from various diseases, complicating drug metabolism and clearance. |

Dosages

Drug (Pregnancy Category) | Pharmacologic Class | Usual Adult Dosage Range | Indications/Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

Opioids | |||

codeine sulfate (D) | Opiate analgesic; opium alkaloid | 15–60mg tid-qid; 10–20 mg every 4–6 hr; do not exceed 120 mg/day | Opioid analgesia, relief of cough |

fentanyl (Duragesic, Oralet, Actiq) (D) | Opioid analgesic | All doses titrated to response; IV/IM: 50–100mcg/dose titrated | Relief of moderate to severe acute pain, chronic pain (including cancer pain) |

hydromorphone (Dilaudid) | Opioid analgesic | IV/IM: 0.25–1mg every 4–6hr; Oral: 2–4 mg PO every 6 hr | 1 mg hydromorphone = 7 mg morphine; opioid analgesia |

meperidine HCl (Demerol) (D) | Opioid analgesic | 50–150mg every 3–4hr prn | Not recommended due to unpredictable effects and risk of seizures |

methadone HCl (Dolophine) (D) | Opioid analgesic | 2.5–10mg every 8–12hr | Opioid analgesia, relief of chronic pain, opioid detoxification, addiction maintenance |

morphine sulfate (MSIR, Roxanol, others) (D) | Opiate analgesic; opium alkaloid | PO: 10–30mg every 4hr prn; IV/IM/SUBQ: 2.5–10 mg every 2–6 hr prn | Opioid analgesia |

morphine sulfate, continuous-release (MS Contin, Oramorph, Kadian) (D) | Opiate analgesic; opium alkaloid | PO: 15–200mg q 8–12hr; cannot be crushed | Relief of moderate to severe pain |

oxycodone, immediate-release (OxyIR) (D) | Opioid, synthetic | 5–20mg every 4–6hr prn | Relief of moderate to severe pain |

oxycodone, continuous-release (OxyContin) (D) | Opioid, synthetic | 10–160mg every 8–12hr; cannot be crushed | Relief of moderate to severe pain |

Opioid Antagonists | |||

naloxone HCl (Narcan) | Opioid antagonist | IV: 0.4–2mg; repeat in 2–8min if needed | Treatment of opioid overdose, postoperative anesthesia reversal |

Nonopioids | |||

acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) (B) | Nonopioid analgesic, antipyretic | 325–650mg every 4–6hr; not to exceed 3–4g/day | Relief of mild to moderate pain |

tramadol (Ultram) | Nonopioid analgesic | 50–100mg every 4–6hr; not to exceed 400mg/day | Relief of moderate to moderately severe pain |

Opioid Agonists

Codeine Sulfate

Classification: Natural opiate alkaloid (Schedule II)

Properties: Similar to morphine in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics; about 10% metabolized to morphine in the body.

Effectiveness: Less effective as an analgesic than morphine; possesses a ceiling effect (increasing the dose will not increase pain relief).

Common Uses: More commonly used as an antitussive in cough preparations.

Combination: Codeine combined with acetaminophen (Schedule III controlled substance) is used for mild to moderate pain and cough relief.

Allergy Misconceptions: GI upset is common; many patients think they are allergic when it may just be gastric discomfort.

Contraindications: Pediatric patients and laboring or breastfeeding mothers.

Dosage Information: For specific dosage guidelines, refer to the previous table.

Clinical Pearl: Codeine is metabolized to morphine in the body.

Pharmacokinetics: Codeine

Route | Onset of Action | Peak Plasma Concentration | Elimination Half-Life | Duration of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

PO | 15–30 min | 34–45 min | 2.5–4 hr | 4–6 hr |

Fentanyl

Classification: Synthetic opioid (Schedule II).

Uses: Treats moderate to severe pain; high abuse potential.

Forms: Available in parenteral injections, transdermal patches (Duragesic), buccal lozenges (Fentora), and buccal lozenges on a stick (Actiq).

Potency: 0.1 mg IV is roughly equivalent to 10 mg of morphine IV.

Chronic Pain: Highly effective in chronic pain syndromes, especially for patients unable to take oral medications.

Administration Notes: Not to be used in opioid-naïve patients or for acute pain relief. Transdermal patches take 6 to 12 hours to provide pain control and are best for non-escalating pain.

Patch Usage: Apply a new patch every 72 hours, and ensure the old patch is removed. Avoid exposing patches to heat; disposal should involve flushing unused patches down the toilet.

FDA Warnings: Fentanyl patches pose risks and are only for opioid-tolerant patients. Care should be taken to keep patches away from children.

Dosage Information: For specific dosage guidelines, refer to the previous table.

Clinical Pearls:

Fentanyl patches take 6 to 12 hours to reach therapeutic levels and last about 17 hours post-removal.

Always remove the old fentanyl patch before applying a new one.

Pharmacokinetics: Fentanyl

Route | Onset of Action | Peak Plasma Concentration | Elimination Half-Life | Duration of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

IV | Rapid | Minutes | 1.5–6 hr | 30–60 min |

Transdermal | 12–24 hr | 48–72 hr | Delayed | 13–40 hr |

PO | 5–15 min | 20–30 min | 5–15 hr | Unknown |

Drug Profiles

Hydromorphone (Dilaudid)

Classification: Schedule II opioid analgesic.

Potency: Approximately seven times more potent than morphine; 1 mg IV or IM is equivalent to 7 mg of morphine.

Medication Errors: Low doses may mislead nurses regarding potency leading to medication errors.

Extended Release: Exalgo is the osmotic extended-release form designed to reduce abuse potential.

Pharmacokinetics: Hydromorphone

Route | Onset of Action | Peak Plasma Concentration | Elimination Half-Life | Duration of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

IV | Rapid | 10–20 min | 2–3 hr | 3–4 hr |

Meperidine Hydrochloride (Demerol)

Classification: Synthetic opioid analgesic (Schedule II).

Cautions: Not recommended for long-term use due to toxic metabolite (normeperidine) that can cause seizures; used in acute settings such as migraine or postoperative shivering.

Forms: Available in oral and injectable forms.

Pharmacokinetics: Meperidine

Route | Onset of Action | Peak Plasma Concentration | Elimination Half-Life | Duration of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

IM | Rapid | 30–60 min | 3–5 hr | 2–4 hr |

Methadone Hydrochloride (Dolophine)

Classification: Synthetic opioid analgesic (Schedule II).

Primary Use: Preferred for the detoxification of opioid addicts in maintenance programs.

Absorption: Readily absorbed with a long half-life; accumulates in tissues allowing for 24-hour dosing.

Cautions: Risk of unintentional overdoses and potential cardiac dysrhythmias.

Pharmacokinetics: Methadone

Route | Onset of Action | Peak Plasma Concentration | Elimination Half-Life | Duration of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

PO | 60–120 min | 1–7.5 hr | 25 hr | 22–48 hr |

Morphine Sulfate

Classification: Naturally occurring alkaloid (Schedule II).

Use: Indicated for severe pain, high potential for abuse.

Forms: Available in oral, injectable, and rectal forms; extended-release available as MS Contin and Kadian.

Caution: Metabolite (morphine-6-glucuronide) can accumulate in renal impairment.

Pharmacokinetics: Morphine Sulfate

Route | Onset of Action | Peak Plasma Concentration | Elimination Half-Life | Duration of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

IV | 5–10 min | 30 min | 2–4 hr | 4 hr |

Oxycodone Hydrochloride

Classification: Schedule II; structurally related to morphine.

Combination Medications: Commonly combined with acetaminophen (Percocet) or aspirin (Percodan); available in immediate-release (Oxy IR) and extended-release (OxyContin).

Hydrocodone Comparison: Weaker but often used in combination with acetaminophen.

Pharmacokinetics (Immediate Release): Oxycodone Hydrochloride

Route | Onset of Action | Peak Plasma Concentration | Elimination Half-Life | Duration of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

PO | 10–15 min | 1 hr | 2–3 hr | 3–6 hr |

Opioid Agonists-Antagonists

Classification: Schedule IV; possess mixed actions with mu receptor binding.

Uses: Suitable for short-term pain control; lower risk of misuse.

Cautions: Can induce withdrawal in opioid-dependent patients; contraindicated in those with hypersensitivity.

Examples: Buprenorphine, butorphanol, nalbuphine, pentazocine, available in multiple forms including transdermal.

Opioid Antagonists

Naloxone Hydrochloride (Narcan): Pure opioid antagonist, indicated for reversing opioid-induced respiratory depression and overdose.

Mechanism: No analgesic properties; primarily causes opioid withdrawal symptoms in opioid-tolerant patients.

Pharmacokinetics: Naloxone Hydrochloride

Route | Onset of Action | Peak Plasma Concentration | Elimination Half-Life | Duration of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

IV | Less than 2 min | Rapid | 64 min | 0.5–2 hr |

Nonopioid and Miscellaneous Analgesics

Acetaminophen (Tylenol)

Common Abbreviation: APAP (not recognized in Canada).

Usage Concern: Movement to stop using APAP to avoid confusion in patients receiving prescriptions with acetaminophen leads them to take additional over-the-counter acetaminophen unknowingly.

NSAIDs

Class Members: Includes aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen, celecoxib (Celebrex), among others.

Indications: Management of pain, especially inflammatory pain like arthritis due to significant anti-inflammatory effects.

Miscellaneous Analgesics

Includes: Tramadol, transdermal lidocaine, and capsaicin (topical product).

Capsaicin: Effective for muscle, joint, and nerve pain by interfering with substance P signals in the brain.

Milnacipran (Savella): A dual-uptake inhibitor indicated for fibromyalgia.

Mechanism of Action and Drug Effects

Acetaminophen: Blocks peripheral pain impulses via inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis, lowers febrile body temperatures by acting on the hypothalamus.

Anti-inflammatory Effects: Acetaminophen lacks anti-inflammatory properties, unlike NSAIDs, and is better tolerated with fewer cardiovascular and GI side effects.

Indications

Mild to Moderate Pain and Fever: An appropriate substitute for aspirin due to its analgesic and antipyretic properties. Particularly useful in children/adolescents to avoid Reye’s syndrome.

Contraindications

Known drug allergy, severe liver disease, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency.

Adverse Effects

Generally well tolerated but can cause skin disorders, nausea, vomiting, and, in severe cases, blood disorders, renal toxicities, and hepatotoxicity (most serious).

Maximum Daily Limits: 4000 mg/day (healthy), 3000 mg/day (older adults), 2000 mg/day (liver disease/chronic alcohol consumers).

Toxicity and Management of Overdose

Risks of Overdose: Ingestion of acute overdoses (150 mg/kg or 7-10 g) can lead to hepatic necrosis. Treatment involves acetylcysteine — most effective within 10 hours of overdose.

Symptoms: Common nausea and unpleasant taste. Better tolerated in IV form.

Interactions

Alcohol: Increases liver toxicity risk; doses should be limited to 2000 mg for chronic alcohol users.

Other Interactions: Drugs like phenytoin, barbiturates, warfarin, isoniazid, and others should be avoided due to potential hepatotoxic effects or altered pharmacodynamics.

Acetaminophen (Tylenol)

Classification: Nonopioid analgesic.

Indications: Effective for mild to moderate pain relief. Best avoided in patients who are alcoholic or have hepatic disease.

Forms: Available in oral, rectal, and intravenous (IV) forms. A component in prescription combination products like hydrocodone/acetaminophen (Vicodin) and oxycodone/acetaminophen (Percocet).

Pharmacokinetics: Acetaminophen

Route | Onset of Action | Peak Plasma Concentration | Elimination Half-Life | Duration of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

PO | 10–30 min | 0.5–2 hr | 1–4 hr | 3–4 hr |

Tramadol Hydrochloride (Ultram)

Classification: Miscellaneous analgesic.

Mechanism: Centrally acting analgesic with a dual mechanism of action; weak bond to mu opioid receptors and inhibits reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin.

Indications: Treatment of moderate to moderately severe pain.

Pharmacokinetics: Rapidly absorbed; absorption unaffected by food; metabolized in the liver; renal excretion.

Adverse Effects: Similar to opioids, including drowsiness, dizziness, headache, nausea, constipation, respiratory depression, and risk of seizures. Increased risk of serotonin syndrome when taken with SSRIs.

Drug Schedule: Rescheduled to class CIV narcotic; some states consider it CII or CIII.

Contraindications: Known drug allergy, including potential cross-reactivity with opioids.

Forms: Available in oral dosage forms, including combinations with acetaminophen (Ultracet), extended-release formulations (ConZip, Ryzolt, Ultram ER), and orally disintegrating tablets (Rybix).

Pharmacokinetics: Tramadol

Route | Onset of Action | Peak Plasma Concentration | Elimination Half-Life | Duration of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

PO | 30 min | 2 hr | 5–8 hr | 6 hr |

Lidocaine (Transdermal)

Classification: Topical anesthetic (patch).

Indications: Treatment for postherpetic neuralgia (pain after shingles).

Application: Patch (Lidoderm) placed on painful areas; up to three patches can be applied to a large area.

Usage Guidelines: Not to be worn longer than 12 hours a day to avoid systemic toxicity. Minimal systemic adverse effects.

Adverse Effects: Mild reactions at the site (redness, edema, unusual sensations) that resolve quickly.

Disposal: Used patches must be secured away from children or pets.

Pharmacokinetics: Lidocaine**

Specific pharmacokinetic data not listed due to continuous nature of dosing. The patch may provide varying degrees of pain relief for 4 to 12 hours.

Nursing Process

Pain may be acute or chronic and occurs in patients in all settings and across the lifespan, leading to suffering and distress. Pain management poses challenges to nurses, prescribers, and other healthcare team members due to its complex nature, requiring astute assessment skills and appropriate individual interventions.

Assessment

Adequate analgesia requires a holistic, comprehensive, and individualized patient assessment with specific attention to the type, intensity, and characteristics of pain and the levels of comfort. Perform a thorough health history, nursing assessment, and medication history upon the first encounter with the patient, including questions about:

Allergies to analgesics (nonopioids, opioids, agonists, antagonists).

Potential drug-drug and drug-food interactions.

Presence of diseases or CNS depression.

History of substance use (alcohol, street drugs) and substance abuse.

Results of laboratory tests indicative of liver and renal function.

Character and intensity of pain, including onset, location, and quality.

Duration of pain (acute vs. chronic).

Types of measures previously implemented and their effectiveness.

Include factors impacting the pain experience, such as physical (age, gender, pain threshold) and emotional, spiritual, and cultural variables. Utilize age-appropriate pain assessment tools, especially in pediatric and older adult patients, and consider nonverbal cues and family input to assess pain levels.

Perform a focused nursing assessment, collecting both subjective and objective data regarding:

Neurologic Status: Level of orientation, sedation, and reflexes.

Respiratory Status: Rate, rhythm, depth, and breath sounds.

GI Status: Bowel sounds, patterns, and discomfort complaints.

Genitourinary Status: Urinary output and symptoms during urination.

Cardiac Status: Pulse rate, blood pressure, dizziness.

Assess and document vital signs, including pain levels, as part of a comprehensive assessment. The acute pain response may elevate sympathetic nervous system values.

Pain Assessment Tools

Numeric Pain Intensity Scale: 0-10 pain rating scale.

Verbal Rating Scale: Descriptive words for pain intensity.

FACES Pain Rating Scale: Series of faces representing pain severity.

FLACC Scale: Used for nonverbal patients to evaluate pain through observable behavior.

Brief Pain Inventory: Multidimensional scale to identify pain impact on functioning.

Patient-Centered Care: Lifespan Considerations for Pediatric Patients

Assessing pain in pediatric patients can be challenging; consider all behaviors indicating pain.

Use tools like the “ouch scale” with face diagrams to determine pain levels (0-5 scale).

Document baseline age, weight, and height for accurate drug calculations.

Administer analgesics before pain escalates; be cautious with dosage forms.

Monitor closely for unusual changes while administering opioids, reporting any significant CNS symptoms immediately.

Follow strict protocols for opioid administration, withholding medications if respirations drop below 12 breaths/min.

Generally, smaller doses with close monitoring are indicated for pediatric patients, with oral medications taken with meals to reduce GI upset.

Nonopioids

For patients receiving nonopioid analgesics, focus the assessment on specific drug details:

Acetaminophen (Tylenol)

Begin by assessing for allergies, pregnancy status, and breastfeeding. Acetaminophen is contraindicated in severe liver disease and G6PD deficiency.

Monitor for potential adverse effects: blood disorders (anemias), liver or kidney toxicity, and symptoms of chronic acetaminophen poisoning (e.g., rapid weak pulse, dyspnea, cold/extremities).

Higher than recommended dosages can lead to liver dysfunction—monitor liver function tests and watch for signs such as loss of appetite, jaundice, nausea, and vomiting.

NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen, aspirin, COX-2 inhibitors)

Assess kidney and liver function and check for GI disorders (e.g., ulcers). Aspirin should not be given to children/adolescents due to Reye’s syndrome risk.

Monitor for bleeding and ulcers, checking for contraindications before therapy.

Tramadol Hydrochloride (Ultram)

Important to assess age; avoid in individuals 75 years or older due to an increased risk of adverse effects.

Lidocaine Transdermal

Indicated for postherpetic neuralgia; assess herpetic lesions and surrounding skin.

Keep patches away from children; use cautiously in very young or debilitated patients due to toxicity risk.

Monitor liver function.

Opioids

When opioid analgesics or CNS depressants are prescribed, the following assessments should be prioritized:

Vital Signs: Focus on respiratory rate, rhythm, depth, and breath sounds due to the risk of respiratory depression.

Neurological Status: Check level of consciousness and sedation.

GI Functioning: Assess bowel sounds and patterns for constipation.

Urinary Functioning: Monitor input and output.

Monitor renal and liver function studies to assess toxicity risk with diminished organ functions.

Consider any personal or family history of neurological disorders (e.g., dementia, stroke) as opioids may mask symptoms.

Opioid Agonists-Antagonists

For patients on opioid agonists-antagonists (e.g., buprenorphine):

Assess vital signs, especially respiratory rate and breath sounds, as they still have CNS depressant effects.

These drugs possess a ceiling effect, and mixing them with other opioids can precipitate withdrawal and reduce analgesic effects.

Age assessment is crucial; contraindicated in patients 18 years old and younger.

Overall, ensure thorough assessments tailored to the specific drug class to ensure safe and effective pain management.

Opioid Antagonists

Use: Opioid antagonists are primarily used to reverse respiratory depression due to opioid overdosage. Naloxone can be administered to patients of all ages, including neonates and children.

Assessment: It is critical to assess and document vital signs before, during, and after the administration of the antagonist to monitor therapeutic effects, determine the need for further doses, and ensure patient safety.

Dosing: Repeated doses may be necessary to completely reverse the effects of opioids since one dose may not be sufficient. Further details on contraindications, cautions, and drug interactions can be found in the pharmacology section.

Human Need Statements

Altered oxygenation, decreased, related to opioid-induced CNS effects and respiratory depression.

Freedom from pain, acute, related to specific disease processes or conditions and other pathologic conditions leading to various levels and types of pain.

Freedom from pain, chronic, related to various disease processes, conditions, or syndromes causing pain.

Altered GI elimination, constipation, related to the CNS depressant effects on the GI system.

Decreased self-determination related to deficient knowledge and lack of familiarity with opioids, their use, and their adverse effects.

Planning: Outcome Identification

Patient regains/maintains a respiratory rate between 10 and 20 breaths/min without respiratory depression while increasing fluid intake and practicing coughing/deep breathing while on opioids or other analgesics for pain.

Patient reports increased comfort levels from acute pain, seen through decreased use of analgesics, increased activity in activities of daily living, and a reduction in complaints of acute pain, with a lower pain rating on a scale of 1 to 10 or alternative scales.

Patient states increased comfort and decreased chronic pain levels, evidenced by reduced analgesic use, increased nonpharmacologic pain relief measures, and greater participation in activities of daily living with lower pain ratings.

Patient identifies strategies to maintain normal bowel elimination patterns and prevent/or minimize opioid-induced constipation by increasing fluid intake and dietary fiber while enhancing mobility.

Patient demonstrates knowledge of appropriate analgesic use with minimal complications/adverse effects and can articulate the rationale, action, and therapeutic effects of the medications they are taking.

Implementation

Once the cause of pain has been diagnosed, begin pain management immediately and aggressively, conforming to the needs of each individual patient and situation. Pain management strategies must incorporate both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches, considering the type, duration, quality, and precipitating factors of pain.

General Principles of Pain Management

Individualize a plan: Based on the patient as a holistic being.

Manage mild pain using nonopioid drugs such as acetaminophen, tramadol, and NSAIDs.

Manage moderate to severe pain with a stepped approach using opioids alongside other analgesics as needed.

Administer analgesics as ordered before pain escalates.

Nonpharmacologic comfort measures: Consider methods such as ice, heat, rest, exercise, and music therapy.

Safety: Herbal Therapies and Dietary Supplements

Feverfew (Chrysanthemum parthenium)

Uses: Migraine headaches, menstrual cramps, inflammation, and fever.

Adverse Effects: Nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, altered taste, muscle stiffness, joint pain.

Drug Interactions: Possible increased bleeding when used with NSAIDs and anticoagulants.

Contraindications: Allergic reactions in those sensitive to ragweed or similar plants.

Nonopioids

Administer as ordered for pain or fever. Acetaminophen should be taken within the recommended dosage range to avoid liver damage. Instruct patients to read medication labels to avoid accidental overdose.

Monitor for overdose signs: Signs include bleeding, loss of energy, fever, sore throat, and easy bruising, which should be reported immediately.

Administration of acetaminophen: Suppositories should not be split or divided for dosage. Cold water may be used to moisten them for easier insertion. Tablets can often be crushed, though not all forms can.

Maximum dosage recommendations: 4000 mg/day for healthy adults, 3000 mg for older adults, and 2000 mg for those with liver disease or chronic alcohol consumption.

Tramadol

Educate about potential side effects: Drowsiness, dizziness, nausea, and constipation. Encourage patients to assist with ambulation if they experience dizziness.

Monitor hydration and fiber intake: Aim to prevent constipation with increased fluid and fiber. Encourage gentle food options for nausea.

Patient Safety and Education

Educate on risks associated with combination medications that contain acetaminophen, particularly with hydrocodone or oxycodone, to prevent overdose.

Use preventive measures: Advise to dangle feet before standing and change positions slowly to avoid dizziness.

Implementation of Opioid Therapy

Once the cause of pain has been diagnosed or assessments have been completed, initiate pain management immediately and aggressively based on each patient’s individual needs and situation. Pain management should include both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches, considering the pain type, rating, quality, duration, and precipitating factors.

General Principles of Pain Management

Individualize a Plan: Tailor care to the patient as a holistic being.

Manage Mild Pain: Use nonopioid drugs such as acetaminophen, tramadol, and NSAIDs.

Manage Moderate to Severe Pain: Utilize a stepped approach with opioids, potentially combining other analgesics.

Timely Administration: Administer analgesics as ordered, prioritizing intervention before pain escalates.

Nonpharmacologic Comfort Measures: Employ methods like ice, heat, elevation, and relaxation techniques.

Safety: Herbal Therapies and Dietary Supplements

Feverfew (Chrysanthemum parthenium)

Uses: Migraine headaches, menstrual cramps, inflammation, fever.

Adverse Effects: Nausea, vomiting, muscle stiffness, altered taste.

Drug Interactions: Increased bleeding risk with NSAIDs and anticoagulants.

Contraindications: Allergy to ragweed, chrysanthemums, or marigolds.

Nonopioids

Administer as indicated for fever or pain.

Acetaminophen: Monitor dosage carefully to avoid liver damage; educate patients on overdose signs (e.g., jaundice, bleeding).

Tramadol may cause drowsiness and dizziness; assist patient with ambulation as needed.

Opioids

Administer after checking the “Nine Rights” of medication administration.

Check previous doses and closely monitor vital signs, particularly respiratory rate, for signs of depression.

Have naloxone readily available, especially for injectable forms.

Monitor urinary output and bowel sounds; maintain vigilance for constipation and urinary retention.

Patient-Centered Care: Lifespan Considerations for Older Adults

Assessment: Record weight and height before therapy; closely monitor vital signs and consciousness level.

Pain Reporting: Older adults may have altered ways to express pain and can retain reliability in reporting even with cognitive impairments.

Opioid Dosage: Use smaller doses with careful monitoring due to increased sensitivity in older adults.

Observe for urinary issues associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Polypharmacy: Assess all medications for potential interactions, emphasizing safety in dosing.

Monitoring and Safety Measures

Conduct frequent assessments of cognition, alertness, and safety measures (e.g., side rails, call bells).

Monitor answers for gradual changes in consciousness or heart rate; ensure the environment is safe to prevent falls.

Be aware of potential adverse effects of opioids, such as hypotension and CNS depression.

Administration of Opioid Forms

Be familiar with the different delivery systems:

Transdermal: Apply to clean, nonhairy areas; rotate sites and dispose of patches securely.

Intravenous: Follow guidelines for administration, monitoring infusion rates, and the impact of dosage.

PCA: Keep track of dosages and patient responses as these systems require focused observation.

Naloxone Administration

Administer during opioid overdose or respiratory depression, giving slowly, monitoring for response, and preparing for potential resuscitation needs.

Ensure that emergency equipment is on hand during administration.

Opioid Agonists-Antagonists

Administration Considerations:

When given alone, opioid agonists-antagonists are effective analgesics, binding to opiate receptors and producing an agonist effect.

If administered alongside other opioids, they can reverse analgesia and precipitate acute withdrawal by blocking opiate receptors.

Monitoring:

Check dosages and routes carefully.

Closely assess vital signs, particularly respiratory rate.

Report any dizziness, constipation, urinary retention, and sedation.

Patient Education:

Inform patients about the potential to reverse analgesia and induce withdrawal when mixed with other opioid agonists.

Provide a list of other opioid agonists for the patient’s awareness.

Opioid Antagonists

Opioid antagonists must be administered as ordered and should be readily available, especially for patients on PCA with opioids, opioid naive patients, or those receiving continuous opioid doses.

Multiple doses of the antagonist may be necessary to achieve adequate reversal of opioid agonists.

Encourage patients to report symptoms like nausea or tachycardia.

Opioid Administration Guidelines

Opioid | Nursing Administration |

|---|---|

Buprenorphine and Butorphanol | IV infusion usually over 3–5 min. Assess respirations before, during, and after use. |

Codeine | Give PO doses with food to minimize GI upset; ceiling effects occur with oral codeine. |

Fentanyl | Administer parenteral doses over 1–2 min, following manufacturer guidelines. Ensure old patches are removed before applying a new one and dispose of properly. |

Hydromorphone | May be given via SUBQ, rectally, IV, or PO. |

Meperidine | Administer via IV, IM, or PO; monitor older adults for increased sensitivity. |

Morphine | Available in various forms; monitor respiratory rate closely. |

Nalbuphine | IV doses of 10 mg given undiluted over 5 min. |

Naloxone | Antagonist for opioid overdose; 0.4 mg typically administered IV over 15 sec or less. |

Oxycodone | Often mixed with acetaminophen or aspirin; available in both immediate and sustained-release forms. |

General Considerations

Knowledge Base: Maintain a current and updated knowledge on all forms of analgesics and pain management protocols, focusing on the specific drugs along with treatment methods for mild to moderate, severe, and special situation pain (e.g., cancer pain). The WHO’s three-step analgesic ladder provides a standard for pain management in cancer patients.

Dosing Importance: Timely treatment before pain becomes severe is crucial, hence pain is regarded as the fifth vital sign. When pain persists over 12 hours a day, analgesic doses should be individualized and administered around the clock to maintain steady-state levels and prevent pain escalation.

Titration of Pain Relief: No single analgesic dosage provides uniform relief across patients. Titration (increasing or decreasing doses) is often necessary based on individual responses. Aggressive titration may be required for difficult pain control cases, especially in cancer pain scenarios.

Combination Therapy: If monotherapy does not suffice, consider adding adjuvants or other drugs to enhance analgesic effects. Examples include:

NSAIDs (for analgesic and antiinflammatory effects)

Acetaminophen (for analgesic effects)

Corticosteroids (for mood elevation and appetite stimulation)

Anticonvulsants (for neuropathic pain)

Tricyclic antidepressants (for neuropathic pain and opioid potentiation)

Local anesthetics (for neuropathic pain)

Dosage Forms: Prefer oral administration, but rectal and transdermal options may be warranted if oral dosing is not appropriate. Transdermal systems provide consistent drug levels and may be used for chronic pain management.

Table 10.8: Drugs Not Recommended for Treatment of Cancer Pain

Class | Drug | Reason for Not Recommending |

|---|---|---|

Opioids with short durations of action | Meperidine | Short duration of analgesia (2-3 hr); may lead to CNS toxicity. |

Miscellaneous | Cannabinoids | Potential adverse effects include dysphoria and hypotension; limited use for nausea. |

Opioid agonists-antagonists | Pentazocine, Butorphanol, Nalbuphine | Possible withdrawal in opioid-dependent patients; ceiling effect; psychologic adverse effects. |

Opioid antagonists | Naloxone | Reversal of analgesia alongside CNS depressant effects. |

Combination preparations | Brompton cocktails | No analgesic benefit over single opioid analgesics. |

Anxiolytics (as monotherapy) or sedatives-hypnotics (as monotherapy) | Benzodiazepines, Barbiturates | Sedation risks without demonstrated analgesic properties, compounding complications. |

Knowt

Knowt