Note

0.0(0)

AP Art History Study Guides

AP Art History Ultimate Guide

Unit 1: Global Prehistory, 30,000–500 BCE

Unit 2: Ancient Mediterranean, 3500 BCE–300 CE

Unit 3: Early Europe and Colonial Americas, 200–1750 CE

Unit 4: Later Europe and Americas, 1750–1980 CE

Unit 5: Indigenous Americas, 1000 BCE–1980 CE

Unit 6: Africa, 1100–1980 CE

Unit 7: West and Central Asia, 500 BCE–1980 CE

Unit 8: South, East, and Southeast Asia, 300 BCE–1980 CE

Unit 9: The Pacific, 700-1980 CE

Unit 10: Global Contemporary, 1980 CE to Present

Studying for another AP Exam?

Check out our other AP study guides

Chapter 25: Japanese Art

Key Notes

- Time Period: 1789–1848

- Culture, beliefs, and physical settings

- Ancient Japanese civilizations were very advanced for their time.

- Shared cultural ideas throughout Asia stimulated artistic production.

- Figural subjects are common in Japanese painting.

- Zen rock gardens and ink paintings were popular in Japan.

- Cultural interactions

- Asian art is influenced by global trends, and in turn influences global trends.

- Trade routes connected Asia with the world.

- Buddhism was imported from Korea and China and was widely popular in part because of courtly patronage.

- Material Processes and Techniques

- The art of Japan is some of the oldest in the world with the longest continuous tradition.

- Distinctive to Japan is the development of rock gardens, teahouses, and wood-block printing.

- Japanese architecture uses natural materials such as wood and stone.

- Calligraphy is highly prized in Japan.

- Elaborate floral and animal-inspired artwork is a Japanese specialty.

- Audience, functions, and patron

- Japanese art featured a counterculture approach that highlighted the achievements of nonprofessional artists with new types of subject matter.

- Architecture is generally religious.

- Theories and Interpretations

- Art history as a science is subject to differing interpretations and theories that change over time.

Historical Background

- Japan has never been successfully invaded by an outside army.

- The Mongols attempted to invade in 1281 but their fleet was destroyed by a typhoon called kamikaze.

- Allies in World War II never invaded Japan's four principal islands.

- Japan has a greater proportion of its traditional artistic patrimony than almost any other country due to relatively sheltered nature and infrequency of foreign interference.

- Commodore Perry opened Japan to outside influence in 1854.

- One by-product of Perry's intervention was the shipment of ukiyo-e prints to European markets.

- Ukiyo-e prints achieved enduring fame in nineteenth-century Europe and America.

- The upper classes in Japan looked down upon ukiyo-e prints and were willing to export them.

Patronage and Artistic Life

- Japanese artists received commissions for their work from both the royal court and religious institutions.

- Workshops were run by masters who had a range of assistants.

- The tradition in Japan was for family-run businesses, with the eldest son inheriting the trade.

- Assistants learned the trade from the ground up, including making paper and ink.

- The master created the composition, while assistants worked on the colors and details.

- Painting was highly regarded in Japan, and both male and female aristocrats learned and excelled in the art form.

Key Terms

- Continuous narrative: a work of art that contains several scenes of the same story painted or sculpted in continuous succession

- Genre painting: painting in which scenes of everyday life are depicted

- Haboku (splashed ink): a monochrome Japanese ink painting done in a free style in which ink seems to be splashed on a surface Kondo: a hall used for Buddhist teachings

- Mandorla: (Italian, meaning “almond”) a term that describes a large almond-shaped orb around holy figures like Christ and Buddha

- Tarashikomi: a Japanese painting technique in which paint is applied to a surface that has not already dried from a previous application

- Ukiyo-e: translated as “pictures of the floating world,” a Japanese genre painting popular from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century

- Yamato-e: a style of Japanese painting that is characterized by native subject matter, stylized features, and thick bright pigments

- Zen: a metaphysical branch of Buddhism that teaches fulfillment through self-discipline and intuition

Zen Buddhism

- Zen is a type of Buddhism that came to East Asia from China in the late twelfth century.

- Zen had a strong influence on Japanese art due to its warm embrace in Japan.

- Zen philosophy rejects materialism and physical adornment, and emphasizes austerity, self-control, courage, and loyalty.

- Meditation is essential for enlightenment, and samurai warriors use it to perform acts of bravery and physical endurance.

- Zen teachings rely on intuition and introspection, rather than books and scripture.

- Both warriors and artists adopted Zen philosophy quickly.

The Japanese Tea Ceremony

- The tea ceremony is a highly sophisticated ritual that may seem simple to the Westerner.

- The ceremony involves simple details, crude vessels, refined tea, and uncomplicated gestures.

- Teahouses have bamboo and wooden walls, floor mats of woven straw, and everything is arranged with straightforwardness and delicacy.

- Visitors enter through a low doorway symbolizing humbleness, into a private setting.

- The space has an unadorned alcove with a Zen painting to enhance an intimate atmosphere of warm and dark spaces.

- Participants sit on the floor in a small space designed for about five people and drink tea.

- The ceremony requires four principles: Purity, harmony, respect, and tranquility.

- All elements of the ceremony are prescribed, including the purification ritual of hand washing and the types of conversation allowed.

Japanese Architecture and Sculpture

- Zen philosophy emphasizes austerity and simplicity in architecture.

- Traditional Japanese structures are usually made of undressed wood and designed to harmonize with the natural environment.

- Pillars are placed at wide intervals to support the roof, creating open interiors that connect with the outdoors.

- Floors are raised to reduce humidity and allow air circulation.

- Eaves are long to provide shade in summer and steeply pitched to allow for quick runoff of rain and snow.

- Interiors have mobile spaces created by sliding screens that act as room dividers.

- Japanese design includes the Zen garden, featuring meticulous arrangements of raked sand, stones, and plants for spiritual refreshment and contemplation.

- Japanese culture has a deep respect for the natural world, reflected in the use of wood for building and stone for Zen gardens.

➼ Todai-ji

Details

- 743; rebuilt on c. 1700

- wood with ceramic tile roofing

- Found in Nara, Japan

Form

- A two-story building with long, graceful eaves hanging over the edges: the eaves protect the interior from the sun and rain.

- Seven external bays on the façade.

Function

- This is the original center of the Buddhist faith in Japan, from which ancillary temples around the country were served.

- The building expresses an imperial and political authority combined with religious overtones.

- It served as a center for the training of scholar monks, who studied Buddhist doctrines.

Context

- The name Great Eastern Temple refers to its location on the eastern edge of the city of Nara, Japan (called Daibutuden).

- The temple is noted for its colossal sculpture of seated Vairocana Buddha.

- The temple and Buddha have been razed several times during military unrest.

- The Buddha is influenced by monumental Chinese sculptures

Image

➼ Great Buddha

Function and Context

- Largest metal statue of Buddha in the world.

- Monumental feat of casting.

- Emperor Shōmu embraced Buddhism and erected sculpture as a way of stabilizing Japanese population during a time of economic crisis.

- Mudra: right hand means “do not fear”; left hand means “welcome.”

Image

➼ Nio Guardian Figures (c. 1203)

Function and Context

- They are placed on either side of the Todai-ji south gate.

- The sculptures are a series of complexly joined woodblock pieces.

- Masculine, frightening figures that protect the Buddha derived from Chinese guardian figures such as those at Luoyang.

- Fierce, forbidding looks and gestures.

- Intricate swirling drapery.

Image

➼ Great South Gate (1181–1203)

Function and Context

- This is the main gate of Todai-ji.

- Nandaimon: great south gate, with five bays—three central bays for passing and two outer bays that are closed.

- The two stories are the same size: unusual in Japanese architecture (usually the upper story is smaller).

- Deep eaves are supported by the six-stepped bracket complex, which rise in tiers with no bracketed arms.

- The roof is supported by huge pillars.

- Unusual in that it has no ceiling; the roof is exposed from below.

- Overall effect is of proportion and stateliness.

Image

➼ Ryoan-Ji

Details

- From Muromachi period

- c. 1480; current design 18th century

- rock garden

- Found in Kyoto, Japan

Garden

- Garden as a microcosm of nature.

- Zen dry garden:

- Gravel represents water; gravel is raked in wavy patterns daily by monks.

- Rocks represent mountain ranges.

- Asymmetrical arrangement.

- The garden is bounded on two sides by a low, yellow wall.

- Fifteen rocks arranged in three groups interpreted as:

- Islands in a floating sea.

- Mountain peaks above clouds.

- Constellations in the sky.

- A tiger taking her cubs across a stream.

- Meant to be viewed from a veranda in a nearby building, the abbot’s residence.

- From no viewpoint is the entire garden viewable at once.

- Garden served as a focus for meditation; in a sense, a garden entered by the mind.

- ■Wet garden:

- Contains a teahouse.

- Seemingly arbitrary in placement, the plants are actually placed in a highly organized and structured environment symbolizing the natural world.

- Water symbolizes purification; used in rituals.

Image

Japanese Painting and Printmaking

- Japanese artists mastered Chinese painting techniques and formats, such as handscrolls, hanging scrolls, and decorative screens.

- Characteristics of Japanese painting style include elevated viewpoints, diagonal lines, and depersonalized faces.

- Haboku, or ink-splashed painting, is a Japanese specialty that creates the illusion of being splashed on the surface in a free and open style.

- Yamato-e, developed in the twelfth century, features tales from Japanese history and literature depicted in long narrative scrolls, with strong diagonals and depersonalized figures.

- Ukiyo-e, or "pictures of the floating world," dominated genre painting in the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries and depicted scenes of everyday life or pleasure.

- Ukiyo-e was immensely popular and produced through a collaborative process between artist, publisher, woodblock carver, and printer.

- Polychrome prints, introduced in 1765, were popular despite being time-consuming and expensive to create, and were known for their subtle and delicate colors separated by black lines.

- Suzuki Harunobu was the first successful ukiyo-e artist in the polychrome tradition, and Hokusai explored the relationship between ukiyo-e and landscape painting.

- Western artists were taken with ukiyo-e prints for their flat areas of color, lack of shadows, odd compositional angles, and unexpected cropping of forms.

➼ Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace

Details

- Kamakura period

- c. 1250–1300

- Handscroll (ink and color on paper)

- Found in Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Form

- A narrative work that is read from right to left as the scroll is unrolled.

- Point of view: one looks down from above onto the scene, which takes place in Kyoto.

- Strong diagonals emphasize movement and action.

- Swift, active brushstrokes.

- Depersonalized figures; many with only one stroke for the eyes, ears, and mouth.

- Tangled mass of forms accentuated by Japanese armor.

- Final scene: lone archer leads the escape from the burning palace with the Japanese commander behind him.

Function: Hand scroll, meant to be read and studied, not meant to be placed on permanent display.

Context

- Military rule in Japan from 1185 on had an interest in the code of the warrior; reflected in the large quantity of war-related literature and paintings.

- Scroll depicts a coup staged in 1159 as Emperor Go-Shirakawa is taken prisoner.

- Burning of the imperial palace at Sanjô in Kyoto as rebel forces try to seize power by capturing a retired emperor.

- Imperial palace in flames; rebels force the emperor to board a cart waiting to take him into captivity.

- Rebels kill those opposed and place their heads on sticks and parade them as trophies.

- Painted a hundred years after the civil war depicted in the scene.

- Unrolls like a film sequence; as one unrolls, time advances.

Image

➼ White and Red Plum Blossoms

Details

- By Ogata Korin

- 1710–1716

- ink, watercolor, and gold leaf on paper

- Found in Museum of Art, Atami, Japan

Form

- A stream cuts rhythmically through the scene; swirls in the paint surface indicate water currents.

- White plum blossoms on left; red on right.

- The artist worked in vivid colors or ink monochrome on gold ground.

- This work has more abstracted and simplified forms than the compositions of Ogata’s predecessors.

- Old tree on left is balanced by new tree on right.

Function: Japanese screen, usually used to separate spaces in a room.

Context

- Japanese rinpa style named for Ogata (Rin, for Ko-rin, and pa, meaning “school”).

- The work is influenced by the yamato-e style of painting.

- Tarashikomi technique, in which paint is applied to a surface that has not already dried from a previous application; creates a dripping effect, useful in depicting streams or flowers.

- The artist was a member of a Kyoto family of textile merchants that serviced samurai, a few nobility, and city dwellers.

Image

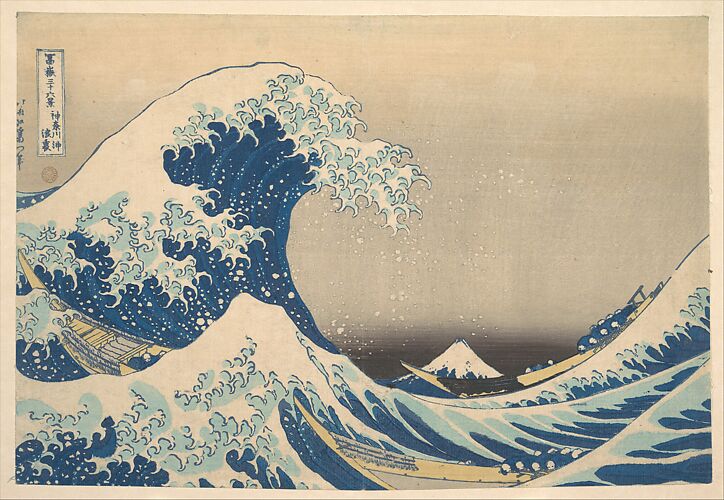

➼ Under the Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa oki nami ura)

Details

- Also known as the Great Wave

- from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji

- 1830–1833

- polychrome wood-block print; ink and color on paper

- Found in Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Form

- Personification of nature; the wave seems intent on drowning the figures in boats.

- Mount Fuji, sacred mountain to the Japanese, seems to be one of the waves.

- The striking design contrasts water and sky with large areas of negative space.

- Imported color: Prussian blue, which made the print seem unusual and special to contemporaries.

Function: Part of series of prints called Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.

Materials and Techniques

- Each wood-block print required the collaboration of a designer, an engraver, a printer, and a publisher.

- Conceived of as a commercial opportunity by the publisher, who may have doubled as a book dealer.

- The publisher determined the theme.

- The print was designed by an artist on paper, and then an engraver copied the design onto a woodblock.

- The printer rubs ink onto the block and places paper over the block to make a print.

- Many colored prints were made by using a separate block for each color.

- Prussian blue was highly prized in Japan; acquired through trade with Europe.

Context

- Mount Fuji, the highest mountain in Japan, is known for its symmetrical cone.

- Mount Fuji is considered a sacred site.

- In Shintoism, the forces of nature unite as one, as they do in the Hokusai print.

- This was the first time a landscape was a major theme in Japanese prints.

Image

Note

0.0(0)

AP Art History Study Guides

AP Art History Ultimate Guide

Unit 1: Global Prehistory, 30,000–500 BCE

Unit 2: Ancient Mediterranean, 3500 BCE–300 CE

Unit 3: Early Europe and Colonial Americas, 200–1750 CE

Unit 4: Later Europe and Americas, 1750–1980 CE

Unit 5: Indigenous Americas, 1000 BCE–1980 CE

Unit 6: Africa, 1100–1980 CE

Unit 7: West and Central Asia, 500 BCE–1980 CE

Unit 8: South, East, and Southeast Asia, 300 BCE–1980 CE

Unit 9: The Pacific, 700-1980 CE

Unit 10: Global Contemporary, 1980 CE to Present

Studying for another AP Exam?

Check out our other AP study guides