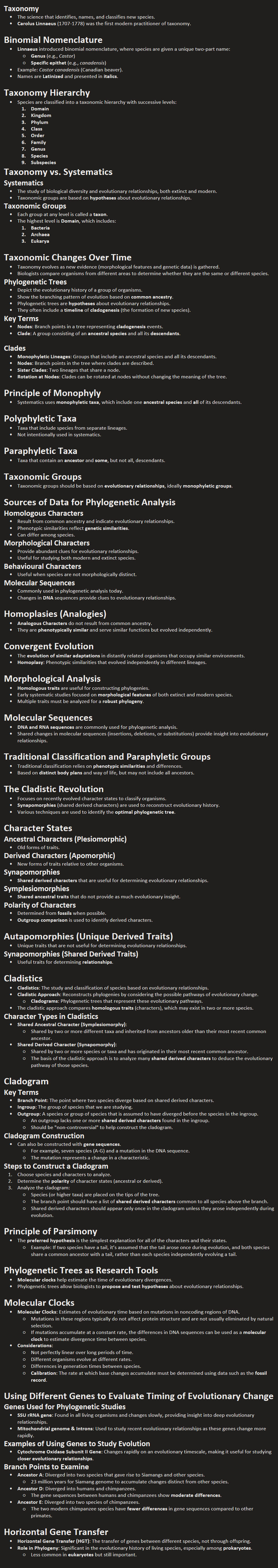

Taxonomy and Systematics

Taxonomy

The science that identifies, names, and classifies new species.

Carolus Linnaeus (1707-1778) was the first modern practitioner of taxonomy.

Binomial Nomenclature

Linnaeus introduced binomial nomenclature, where species are given a unique two-part name:

Genus (e.g., Castor)

Specific epithet (e.g., canadensis)

Example: Castor canadensis (Canadian beaver).

Names are Latinized and presented in italics.

Taxonomy Hierarchy

Species are classified into a taxonomic hierarchy with successive levels:

Domain

Kingdom

Phylum

Class

Order

Family

Genus

Species

Subspecies

Taxonomy vs. Systematics

Systematics

The study of biological diversity and evolutionary relationships, both extinct and modern.

Taxonomic groups are based on hypotheses about evolutionary relationships.

Taxonomic Groups

Each group at any level is called a taxon.

The highest level is Domain, which includes:

Bacteria

Archaea

Eukarya

Taxonomic Changes Over Time

Taxonomy evolves as new evidence (morphological features and genetic data) is gathered.

Biologists compare organisms from different areas to determine whether they are the same or different species.

Phylogenetic Trees

Depict the evolutionary history of a group of organisms.

Show the branching pattern of evolution based on common ancestry.

Phylogenetic trees are hypotheses about evolutionary relationships.

They often include a timeline of cladogenesis (the formation of new species).

Key Terms

Nodes: Branch points in a tree representing cladogenesis events.

Clade: A group consisting of an ancestral species and all its descendants.

Clades

Monophyletic Lineages: Groups that include an ancestral species and all its descendants.

Nodes: Branch points in the tree where clades are described.

Sister Clades: Two lineages that share a node.

Rotation at Nodes: Clades can be rotated at nodes without changing the meaning of the tree.

Principle of Monophyly

Systematics uses monophyletic taxa, which include one ancestral species and all of its descendants.

Polyphyletic Taxa

Taxa that include species from separate lineages.

Not intentionally used in systematics.

Paraphyletic Taxa

Taxa that contain an ancestor and some, but not all, descendants.

Taxonomic Groups

Taxonomic groups should be based on evolutionary relationships, ideally monophyletic groups.

Sources of Data for Phylogenetic Analysis

Homologous Characters

Result from common ancestry and indicate evolutionary relationships.

Phenotypic similarities reflect genetic similarities.

Can differ among species.

Morphological Characters

Provide abundant clues for evolutionary relationships.

Useful for studying both modern and extinct species.

Behavioural Characters

Useful when species are not morphologically distinct.

Molecular Sequences

Commonly used in phylogenetic analysis today.

Changes in DNA sequences provide clues to evolutionary relationships.

Homoplasies (Analogies)

Analogous Characters do not result from common ancestry.

They are phenotypically similar and serve similar functions but evolved independently.

Convergent Evolution

The evolution of similar adaptations in distantly related organisms that occupy similar environments.

Homoplasy: Phenotypic similarities that evolved independently in different lineages.

Morphological Analysis

Homologous traits are useful for constructing phylogenies.

Early systematic studies focused on morphological features of both extinct and modern species.

Multiple traits must be analyzed for a robust phylogeny.

Molecular Sequences

DNA and RNA sequences are commonly used for phylogenetic analysis.

Shared changes in molecular sequences (insertions, deletions, or substitutions) provide insight into evolutionary relationships.

Traditional Classification and Paraphyletic Groups

Traditional classification relies on phenotypic similarities and differences.

Based on distinct body plans and way of life, but may not include all ancestors.

The Cladistic Revolution

Focuses on recently evolved character states to classify organisms.

Synapomorphies (shared derived characters) are used to reconstruct evolutionary history.

Various techniques are used to identify the optimal phylogenetic tree.

Character States

Ancestral Characters (Plesiomorphic)

Old forms of traits.

Derived Characters (Apomorphic)

New forms of traits relative to other organisms.

Synapomorphies

Shared derived characters that are useful for determining evolutionary relationships.

Symplesiomorphies

Shared ancestral traits that do not provide as much evolutionary insight.

Polarity of Characters

Determined from fossils when possible.

Outgroup comparison is used to identify derived characters.

Autapomorphies (Unique Derived Traits)

Unique traits that are not useful for determining evolutionary relationships.

Synapomorphies (Shared Derived Traits)

Useful traits for determining relationships.

Cladistics

Cladistics: The study and classification of species based on evolutionary relationships.

Cladistic Approach: Reconstructs phylogenies by considering the possible pathways of evolutionary change.

Cladograms: Phylogenetic trees that represent these evolutionary pathways.

The cladistic approach compares homologous traits (characters), which may exist in two or more species.

Character Types in Cladistics

Shared Ancestral Character (Symplesiomorphy):

Shared by two or more different taxa and inherited from ancestors older than their most recent common ancestor.

Shared Derived Character (Synapomorphy):

Shared by two or more species or taxa and has originated in their most recent common ancestor.

The basis of the cladistic approach is to analyze many shared derived characters to deduce the evolutionary pathway of those species.

Cladogram

Key Terms

Branch Point: The point where two species diverge based on shared derived characters.

Ingroup: The group of species that we are studying.

Outgroup: A species or group of species that is assumed to have diverged before the species in the ingroup.

An outgroup lacks one or more shared derived characters found in the ingroup.

Should be "non-controversial" to help construct the cladogram.

Cladogram Construction

Can also be constructed with gene sequences.

For example, seven species (A-G) and a mutation in the DNA sequence.

The mutation represents a change in a characteristic.

Steps to Construct a Cladogram

Choose species and characters to analyze.

Determine the polarity of character states (ancestral or derived).

Analyze the cladogram:

Species (or higher taxa) are placed on the tips of the tree.

The branch point should have a list of shared derived characters common to all species above the branch.

Shared derived characters should appear only once in the cladogram unless they arose independently during evolution.

Principle of Parsimony

The preferred hypothesis is the simplest explanation for all of the characters and their states.

Example: If two species have a tail, it’s assumed that the tail arose once during evolution, and both species share a common ancestor with a tail, rather than each species independently evolving a tail.

Phylogenetic Trees as Research Tools

Molecular clocks help estimate the time of evolutionary divergences.

Phylogenetic trees allow biologists to propose and test hypotheses about evolutionary relationships.

Molecular Clocks

Molecular Clocks: Estimates of evolutionary time based on mutations in noncoding regions of DNA.

Mutations in these regions typically do not affect protein structure and are not usually eliminated by natural selection.

If mutations accumulate at a constant rate, the differences in DNA sequences can be used as a molecular clock to estimate divergence time between species.

Considerations:

Not perfectly linear over long periods of time.

Different organisms evolve at different rates.

Differences in generation times between species.

Calibration: The rate at which base changes accumulate must be determined using data such as the fossil record.

Using Different Genes to Evaluate Timing of Evolutionary Change

Genes Used for Phylogenetic Studies

SSU rRNA gene: Found in all living organisms and changes slowly, providing insight into deep evolutionary relationships.

Mitochondrial genome & Introns: Used to study recent evolutionary relationships as these genes change more rapidly.

Examples of Using Genes to Study Evolution

Cytochrome Oxidase Subunit II Gene: Changes rapidly on an evolutionary timescale, making it useful for studying closer evolutionary relationships.

Branch Points to Examine

Ancestor A: Diverged into two species that gave rise to Siamangs and other species.

23 million years for Siamang genome to accumulate changes distinct from other species.

Ancestor D: Diverged into humans and chimpanzees.

The gene sequences between humans and chimpanzees show moderate differences.

Ancestor E: Diverged into two species of chimpanzees.

The two modern chimpanzee species have fewer differences in gene sequences compared to other primates.

Horizontal Gene Transfer

Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT): The transfer of genes between different species, not through offspring.

Role in Phylogeny: Significant in the evolutionary history of living species, especially among prokaryotes.

Less common in eukaryotes but still important.