Wk5,6 - ECOS2002_Sem2_2024_Topic4

4. The AD-AS Model

The Aggregate Demand-Aggregate Supply (AD-AS) model outlines the dynamics of price levels and equilibrium output. It explains the aggregate demand function and how production costs relate to the price level. Key concepts include:

Equilibrium Output: The intersection of the AD and AS curves represents the economy's output at a given price level.

Aggregate Supply: It is influenced by diminishing returns and expectations, impacting short-run outputs and prices.

Natural Level of Output: Defined by the long-run aggregate supply function (LAS), it reflects conditions where markets clear, and resources are fully employed.

Adjustment to Long-run Equilibrium: Explains how the economy recovers from shocks over time.

Macro Policy Implications: Policymakers can use the AD-AS framework to analyze the effects of fiscal and monetary policy interventions.

Derivation of the AD Function

The downward sloping Aggregate Demand (AD) function results from three primary mechanisms signaling that a rise in global price levels lowers planned expenditures:

Monetary Policy Reaction Effect: Central banks adjust interest rates based on inflation targets, which influences consumer spending and investment.

Wealth Effect: Increased prices diminish the purchasing power of wealth, reducing consumption.

International Competitiveness Effect: Rising domestic price levels can hamper exports by affecting the real exchange rate adversely. Concerns about the robustness of the wealth and international competitiveness effects challenge the theoretical underpinnings of the AD function.

‘Monetary Policy Reaction’ Effect

Monetary policy focuses primarily on controlling inflation, establishing a price target (PT) for the long run. The preferred interest rate adjusts as the price level fluctuates around this target.

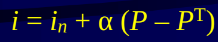

describe how the nominal interest rate ii is set in response to deviations in inflation or other economic variables

The general formula is:

i = in + a(P - PT)

i: This represents the nominal interest rate set by the central bank.

i_n: This is the natural or neutral interest rate, which is the rate that would prevail if the economy were at full employment and inflation were at its target level.

α\alpha: This is a coefficient that measures the responsiveness of the interest rate to deviations from the target.

P: This represents the actual level of inflation.

P^T: This is the target level of inflation set by the central bank.

This framework insists that, over time, equilibrium will reach the target price level, influencing both production and consumption patterns.

Wealth and International Competitiveness Effects

Wealth Effect: As general price levels rise, the real value of nominal wealth decreases, diminishing consumption. The wealth effect’s impact is tempered by counteracting changes in the real value of debt held by consumers, therefore blurring the expected outcomes on overall spending.

International Competitiveness Effect: In an open economy, an increase in domestic price levels (PT) can render exports less competitive. The effect is particularly significant in more open economies, where exchange rates and foreign price levels dictate net export dynamics.

Slope and Shifts of the AD Function

The AD function's slope is contingent on multiple factors affecting how aggregate expenditures react to price fluctuations:

The degree of openness of the economy.

Sensitivity of expenditure related to wealth.

The central bank's commitment to interest rate adjustments based on inflation targets.

Sensitivity of planned expenditures to interest rates.

Shifts in the AD function occur due to alterations in total expenditures unrelated to price changes, such as fiscal policy changes or external shocks, significantly affecting the dynamics of aggregate demand.

Long run equilibrium has price level at 1.

Short-Run Aggregate Supply (SAS) Function

The upward sloping SAS function results from several rationales, primarily due to diminishing returns to variable inputs (labor and materials) in production. As output rises, using variable factors more intensely leads to increasing production costs, thus driving prices higher. Fundamental assumptions underlying the SAS include:

Fixed productive capacities and input prices in the short run.

Changes in input prices will adjust corresponding production costs, thereby necessitating higher prices to maintain profitability.

Long-Run Aggregate Supply (LAS) Function

In traditional macroeconomic theory, LAS is predicated on the economy’s capacity converging at a natural output level (YN) wherein stable price and wage levels are observed due to equilibrium across labor, capital, and product markets. This natural output is characterized by a 'natural' unemployment rate, aligning with conditions where no excess demand or supply exists.

Wage-Price Flexibility and Rigidity

Debate exists on whether wages and prices adjust flexibly to reach market equilibrium. Proponents of laissez-faire argue that markets efficiently self-correct, while Keynesian perspectives highlight rigidity issues that prevent swift adjustments, suggesting that government intervention might be necessary to stimulate the economy under certain circumstances.

Monetary Policy and Fiscal Expansion

Monetary policy effectively influences short-term economic fluctuations but is neutrally positioned concerning real variables in the long run. Fiscal expansion poses a risk of crowding out private investment if aggregate demand exceeds the natural output level, prompting inflationary pressures that necessitate counteracting measures from central banks.

Summary of AS-AD Equilibrium Conditions

Long-Run Equilibrium: Achieved when output is at its natural level, corresponding with no involuntary unemployment and price stability.

Short-Run Equilibrium: Defined by potential excess demands or supplies, with real wage adjustments necessary to navigate back to long-term stability. The intricate relationship between AD and AS provides a framework for understanding overall economic performance and policy implications.