Chapter 23: TRANSITION METALS AND COORDINATION CHEMISTRY

The Transition Metals

Minerals — Metallic elements found in nature as solid inorganic compounds.

Metallurgy — The science and technology of extracting metals from their natural sources and preparing them for practical use.

It usually involves several steps:

Mining — Removing the relevant ore from the ground.

Concentrating the ore or otherwise preparing it for further treatment.

Reducing the ore to obtain the free metal.

Purifying the metal.

Mixing it with other elements to modify its properties.

Alloy — A metallic material composed of two or more elements.

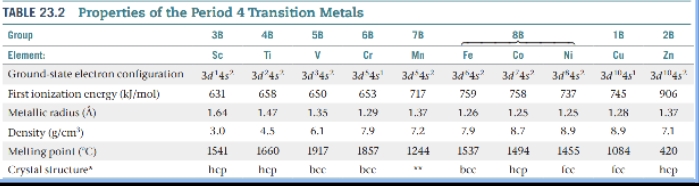

Physical Properties

Electron Configurations and Oxidation States

Transition metals owe their location in the periodic table to the filling of the d subshells. Many of the chemical and physical properties of transition metals result from the unique characteristics of the d orbitals.

Most transition-metal ions contain partially occupied d subshells, which are responsible in large part for three characteristics:

Transition metals often have more than one stable oxidation state.

Many transition-metal compounds are colored.

Transition metals and their compounds often exhibit magnetic properties.

Magnetism

Magnetic Moment — A property that causes the electron to behave like a tiny magnet.

Diamagnetic Solid — All the electrons in a solid are paired, the spin-up and spin-down electrons cancel one another.

Diamagnetic substances are generally described as being nonmagnetic, but when a diamagnetic substance is placed in a magnetic field, the motions of the electrons cause the substance to be very weakly repelled by the magnet.

Paramagnetic — A substance in which the atoms or ions have one or more unpaired electrons.

In a paramagnetic solid, the electrons on one atom or ion do not influence the unpaired electrons on neighboring atoms or ions.

Ferromagnetism — a form of magnetism much stronger than paramagnetism.

It arises when the unpaired electrons of the atoms or ions in a solid are influenced by the orientations of the electrons in neighboring atoms or ions.

Permanent Magnet: When a ferromagnet is removed from an external magnetic field, the interactions between the electrons cause the ferromagnetic substance to maintain a magnetic moment.

Antiferromagnetism — The unpaired electrons on a given atom or ion align so that their spins are oriented in the direction opposite the spin direction on neighboring atoms.

Ferrimagnetism — Has both ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic characteristics.

The unpaired electrons align so that the spins in adjacent atoms or ions point in opposite directions.

Transition-Metal Complexes

Metal Complexes — Species that are assemblies of a central transition-metal ion bonded to a group of surrounding molecules or ions.

Coordination Compounds — Compounds that contain complexes.

Ligands — The molecules or ions that bond to the metal ion in a complex.

The Development of Coordination Chemistry: Werner’s Theory

Alfred Werner — Proposed the Werner’s Theory. He proposed that any metal ion exhibits both a primary valence and a secondary valence.

Primary Valence — The oxidation state of the metal.

Secondary Valence — The number of atoms bonded to the metal ion.

In writing the chemical formula for a coordination compound, Werner suggested using square brackets to signify the makeup of the coordination sphere in any given compound.

He further proposed that the chloride ions that are part of the coordination sphere are bound so tightly that they do not dissociate when the complex is dissolved in water.

The Metal–Ligand Bond

It is the bond between a ligand and a metal ion forms as a result of a Lewis acid–base interaction.

Because the ligands have available pairs of electrons, they can function as Lewis bases (electron-pair donors).

Metal ions have empty valence orbitals, so they can act as Lewis acids .

A metal complex is a distinct chemical species that has physical and chemical properties different from those of the metal ion and ligands from which it is formed.

Hydrated metal ions are complexes in which the ligand is water.

Chares, Coordination Numbers, and Geometries

The charge of a complex is the sum of the charges on the metal and on the ligands

The coordination number of a metal ion is often influenced by the relative sizes of the metal ion and the ligands.

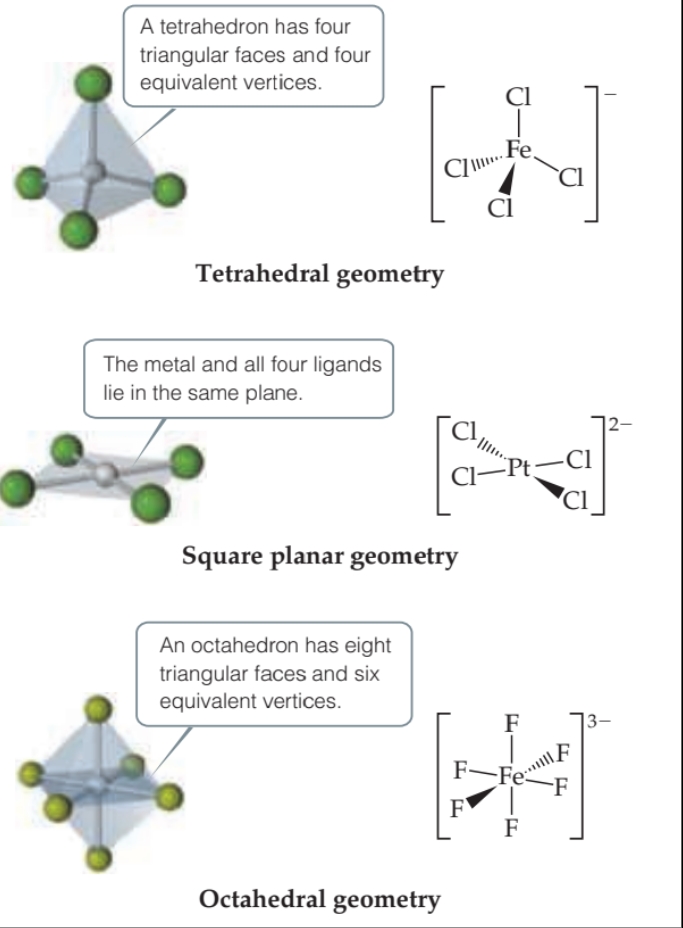

The most common coordination geometries for coordination complexes are shown in the table below.

The tetrahedral geometry is the more common of the two and is especially prevalent among nontransition metals.

The square planar geometry is characteristic of transition-metal ions with eight d electrons in the valence shell

Common Ligands in Coordination Chemistry

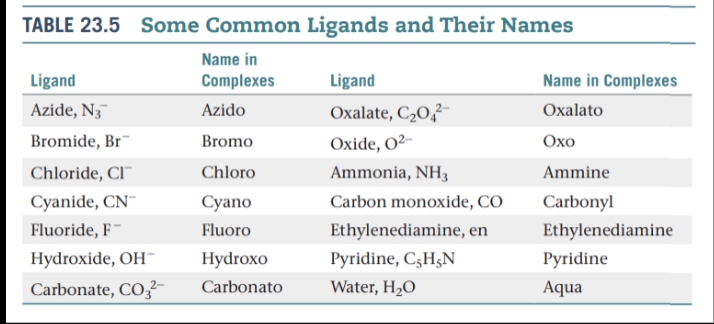

Donor Atom — The ligand atom that binds to the central metal ion in a coordination complex.

Monodentate ligands — Ligands having only one donor atom. They are able to occupy only one site in a coordination sphere.

Bidentate ligands — Ligands having two donor atoms.

Polydentate ligands — Ligands have three or more donor atoms.

Chelating Agents — Bidentate and polydentate ligands.

They are often used to prevent one or more of the customary reactions of a metal ion without removing the ion from solution.

Chelate effect — The trend of generally larger formation constants for bidentate and polydentate ligands.

Metals and Chelates in Living Systems

Among the most important chelating agents in nature are those derived from the porphine molecule.

This molecule can coordinate to a metal via its four nitrogen donor atoms.

Porphyrins — Complexes formed once porphine bonds to a metal ion, the two H atoms on the nitrogens are displaced.

Two important porphyrins are hemes, in which the metal ion is Fe(II), and chlorophylls, with a Mg(II) central ion.

Myoglobin — A globular protein, one that folds into a compact, roughly spherical shape.

Found in the cells of skeletal muscle, particularly in seals, whales, and porpoises.

It stores oxygen in cells, one molecule of O2 per myoglobin, until it is needed for metabolic activities.

Hemoglobin — The protein hat transports oxygen in human blood, is made up of four heme-containing subunits, each of which is very similar to myoglobin.

Chlorophylls — Are porphyrins that contain Mg(II); are the key components in the conversion of solar energy into forms that can be used by living organisms.

Nomenclature and Isomerism in Coordination Chemistry

How to Name Coordination Compounds

In naming complexes that are salts, the name of the cation is given before the name of the anion.

In naming complex ions or molecules, the ligands are named before the metal. Ligands are listed in alphabetical order, regardless of their charges. Prefixes that give the number of ligands are not considered part of the ligand name in determining alphabetical order.

The names of anionic ligands end in the letter o, but electrically neutral ligands ordinarily bear the name of the molecules.

Greek prefixes (di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, hexa-) are used to indicate the number of each kind of ligand when more than one is present. If the ligand contains a Greek prefix or is polydentate, the alternate prefixes bis-, tris-, tetrakis-, pentakis-, and hexakis- are used and the ligand name is placed in parentheses.

If the complex is an anion, its name ends in -ate.

The oxidation number of the metal is given in parentheses in Roman numerals following the name of the metal.

Isomerism

It is when two or more compounds have the same composition but a different arrangement of atoms.

Two main kinds of Isomerism:

Structural Isomers — which have different bonds.

**Stereoisomers —**which have the same bonds but different ways in which the ligands occupy the space around the metal center.

Structural Isomerism

Linkage isomerism — A relatively rare but interesting type that arises when a particular ligand is capable of coordinating to a metal in two ways.

Coordination-sphere isomers — are isomers that differ in which species in the complex act as ligands, and which are outside the coordination sphere.

Stereoisomerism

Geometric Isomerism — in which the arrangement of the atoms is different but the same bonds are present.

They generally have different physical properties and may also have markedly different chemical reactivities.

They are also possible in octahedral complexes when two or more different ligands are present.

Optical Isomerism — called d enantiomers, are mirror images that cannot be superimposed on each other.

They bear the same resemblance to each other that your left hand bears to your right hand.

They are usually distinguished from each other by their interaction with plane-polarized light.

Color and Magnetism in Coordination Chemistry

Color

The color of a complex depends on the identity of the metal ion, on its oxidation state, and on the ligands bound to it.

When an object absorbs some portion of the visible spectrum, the color we perceive is the sum of the unabsorbed portions, which are either reflected or transmitted by the object and strike our eyes.

If an object absorbs all wavelengths of visible light, none reaches our eyes and the object appears black.

If it absorbs no visible light, it is white if opaque or colorless if transparent.

If it absorbs all but orange light, the orange light is what reaches our eye and therefore is the color we see.

An interesting phenomenon of vision is that we also perceive an orange color when an object absorbs only the blue portion of the visible spectrum and all the other colors strike our eyes.

This is because orange and blue are complementary colors, which means that the removal of blue from white light makes the light look orange.

Absorption Spectrum — The amount of light absorbed by a sample as a function of wavelength.

Magnetism of Coordination Compounds

Many transition-metal complexes exhibit paramagnetism.

In such compounds, the metal ions possess some number of unpaired electrons.

It is possible to experimentally determine the number of unpaired electrons per metal ion from the measured degree of paramagnetism, and experiments reveal some interesting comparisons.

Crystal-Field Theory

Crystal-Field Theory — Fdeveloped to explain the properties of solid crystalline materials.

In crystal-field theory, we consider the ligands to be negative points of charge that repel the negatively charged electrons in the d orbitals of the metal ion.

It helps us account for the colors observed in transition-metal complexes.

Octahedral crystal-field — There are six ligands attached to the central transition metal.

Crystal-Field Splitting Energy — The energy gap between two sets.

Spectrochemical series — Ligands are arranged in order of their abilities to increase the crystal-field splitting energy.

Electron Configurations in Octahedral Complexes

Spin-Pairing Energy — The energy required to place that electron in an empty orbital.

It arises from the fact that the electrostatic repulsion between two electrons that share an orbital is greater than the repulsion between two electrons that are in different orbitals and have parallel spins.

The [CoF6]^3 - complex is a high-spin complex; that is, the electrons are arranged so that they remain unpaired as much as possible.

The [Co(CN)6]^3 - ion is a low-spin complex; that is, the electrons are arranged so that they remain paired as much as possible.

Tetrahedral and Square-Planar Complexes

Four equivalent ligands can interact with a central metal ion most effectively by approaching along the vertices of a tetrahedron. In this geometry the lobes of the two e orbitals point toward the edges of the tetrahedron, exactly in between the ligands.

The crystal-field splitting energy ∆ is much smaller for tetrahedral complexes than it is for comparable octahedral complexes, in part because there are fewer ligand point charges in the tetrahedral geometry, and in part because neither set of orbitals has lobes that point directly at the ligands.

In a square-planar complex, four ligands are arranged about the metal ion such that all five species are in the xy plane.

Knowt

Knowt