Unit 1

What Is Cognitive Psychology?

Example Scenario:

You’re walking along a dark, unfamiliar city street. It’s raining and foggy, and you are cold and a bit apprehensive. As you walk past a small alley, you catch some movement out of the corner of your eye. You turn to look down the alley and start to make out a shape coming toward you. As the shape draws nearer, you are able to make out more features, and you realize that it’s...

^Cognitive psychology aims to understand this kind of complex mental processing

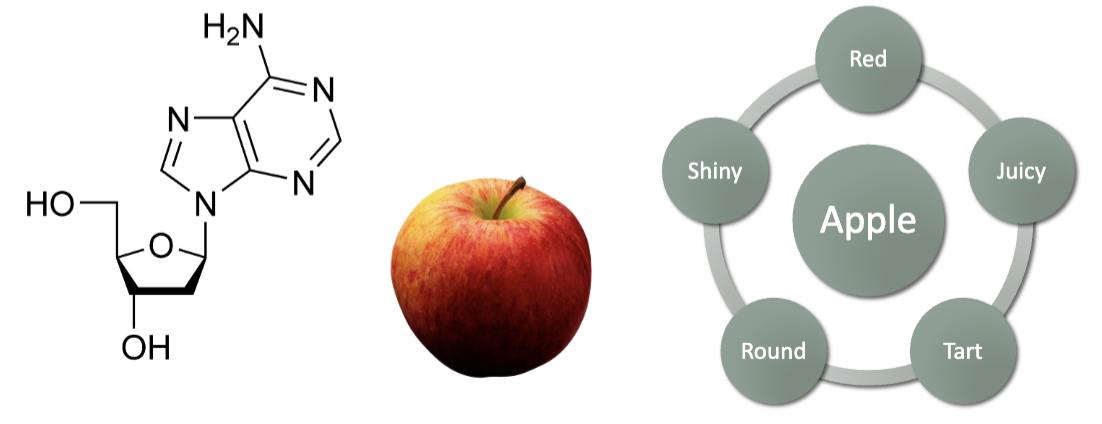

the branch of psychology that is concerned with how people acquire, store, transform, use, and communicate information

study of mental processes by which humans learn about and interact with the world

Specific Topics

perception

attention

memory

language

problem-solving

planning

influences on cognitive psychology:

philosophical antecedents

philosophical influences on the study of cognition

empiricism vs. nativism

nurture vs. nature

ENVIRONMENT/EXPERIENCES

Aristotle

Locke

“blank slate”

HEREDITY & BIOLOGY

Descartes

Plato

psychological antecedents

Wilhelm Wundt (1832-1920)

structuralism

introspection

William James (1842-1910)

Principles of Psychology (1890)

functionalism

Hermann von Ebbinghaus (1850-1909)

experimental observation

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939)

subconscious

Karl Popper (1902-1994)

philosopher of science

falsifiability

can make progress by disproving theories as well as proving theories

Gestalt Psychology

the whole is greater than the sum of the parts

behaviorism

Ivan Pavlov (1849-1936)

classical conditioning

Thorndike (1874-1949)

instrumental/operant conditioning

reinforcement, punishment

behaviorism takes over American psychology

mental processes unobservable

should simply describe the relationship between stimuli and responses

introspection rejected

concepts such as ID, Ego, and Superego rejected as untestable fantasies

John Broadus Watson (1878-1958)

radical behaviorism

Burhus Frederic Skinner (1904-1990)

continues to push for “radical behaviorism”

all behavior (even language) is the result of classical and instrumental/operant conditioning

“verbal behavior” (1957)

the decline of behaviorism

other science requires unobservable theoretical entities (atoms, genes, gravity)

still passes Popper’s test

Edward C. Tolman (1886-1959)

internal representations

cognitive maps

Noam Chomsky (1928-)

refutes Skinner’s attempts to explain language in “verbal behavior”

critique (1959) had big impact on behaviorism

the post-war context

developments during and after war

engineering

idea of humans as information processors

thinking as computation

development of computers made concept of thinking-as-computation more plausible

artificial intelligence

computers’ ability to do “smart” things (chess)

thinking-as-computation even more plausible

early cognitive psychology

late 1950s, early 1960s

“computer metaphor” is psychology

one type of information processing approach

consequences

architecture of mind

seperate systems

how large

sequences of steps during cognitive processing

format of information

parts of a task

how quickly performed

“information processing” approach

subtypes

1967: first textbook

Cognitive Psychology by Ulric Neisser

cognitive science

intersection of several disciplines including:

psychology

linguistics

philosophy

computer science

computer simulation

neuroscience

aim:

integrate cognitive science, neuroimaging, neuropsychology

computer metaphor gradually losing favor

“network metaphor”

cognitive psychology today

increasing emphasis on:

formal models

neuroscience

fine-grained measures

statistical analyses

still information processing approach

“network” metaphor > computer metaphor

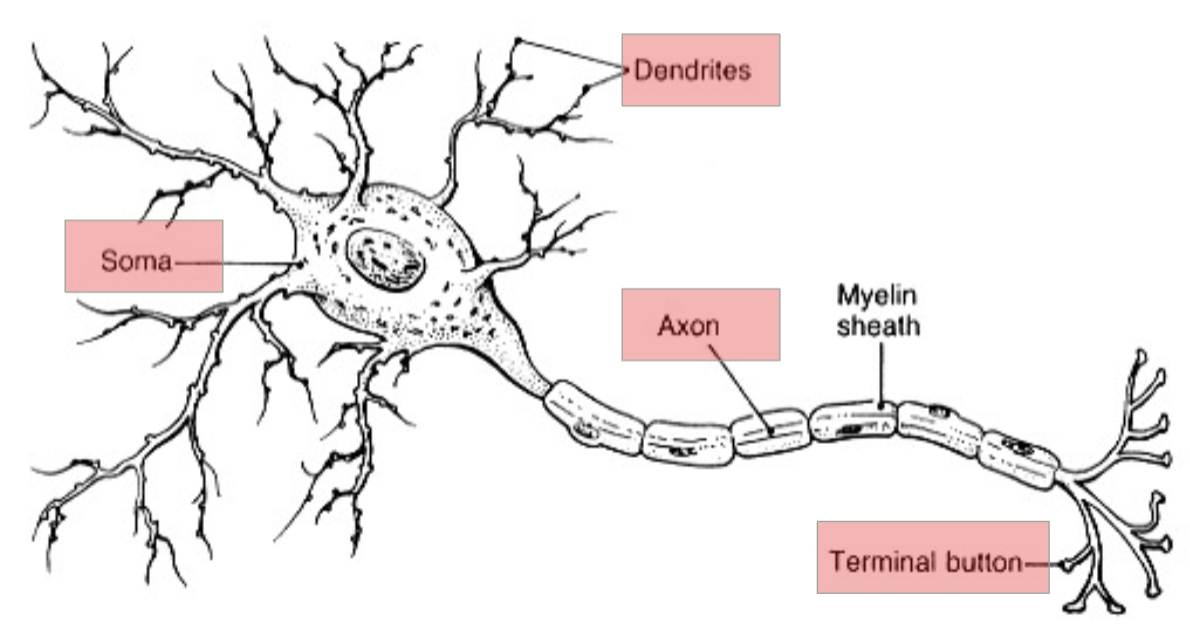

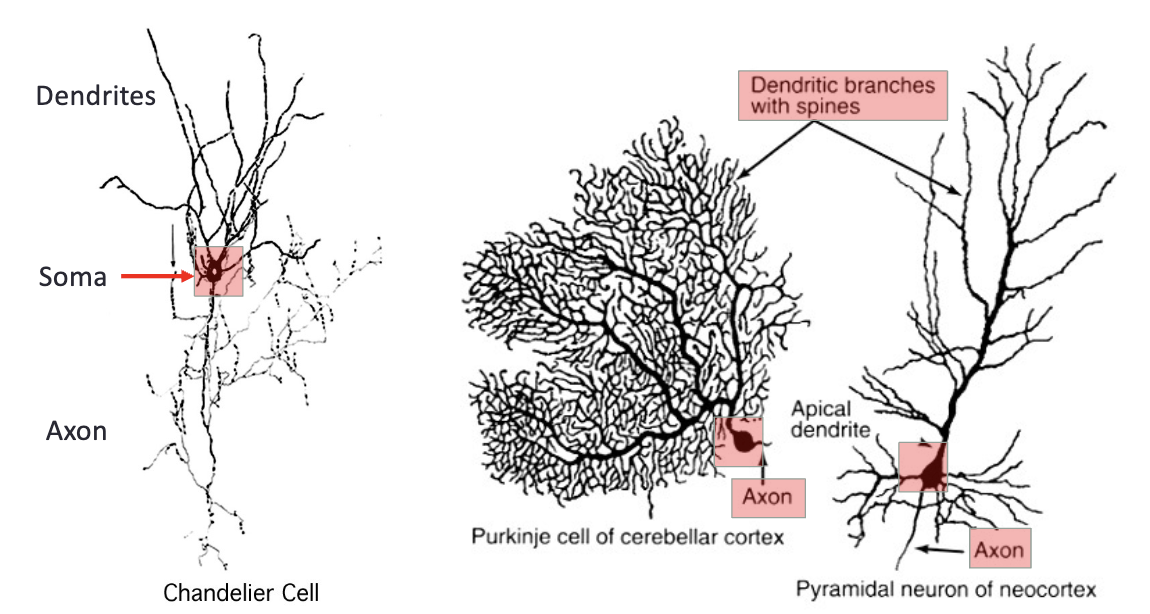

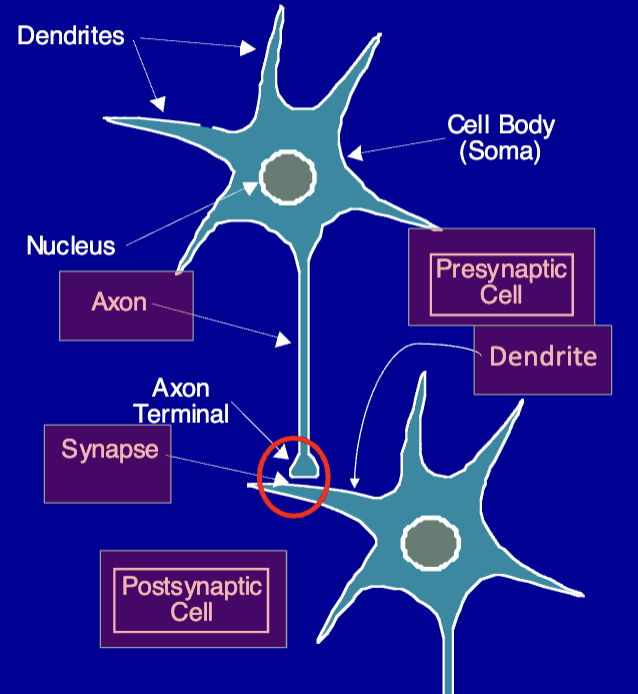

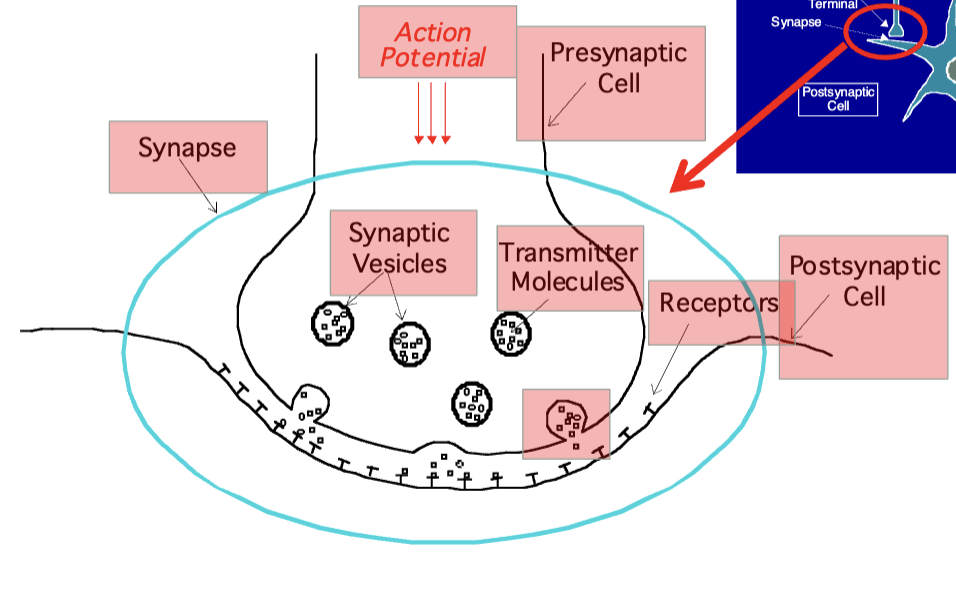

neural information processing and learning

information transmission in the brain

neural basis of learning

information transmission

presynaptic action potential

neurotransmitter release

neurotransmitter binding

ion flow

postsynaptic potential

excitatory postsynaptic potential may - action potential (spike)

inhibitory postsynaptic potential may - prevent spike

information flow

basis of all cognitive (and non-cognitive) processing

determined by synaptic strengths between neurons

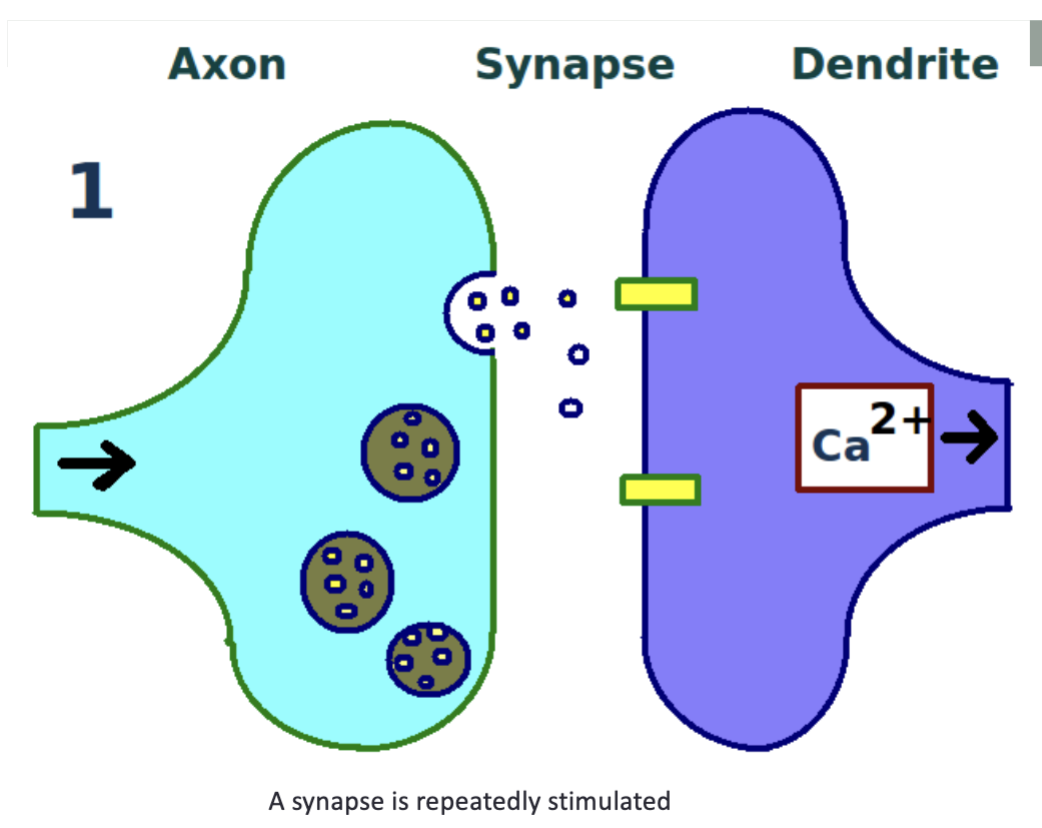

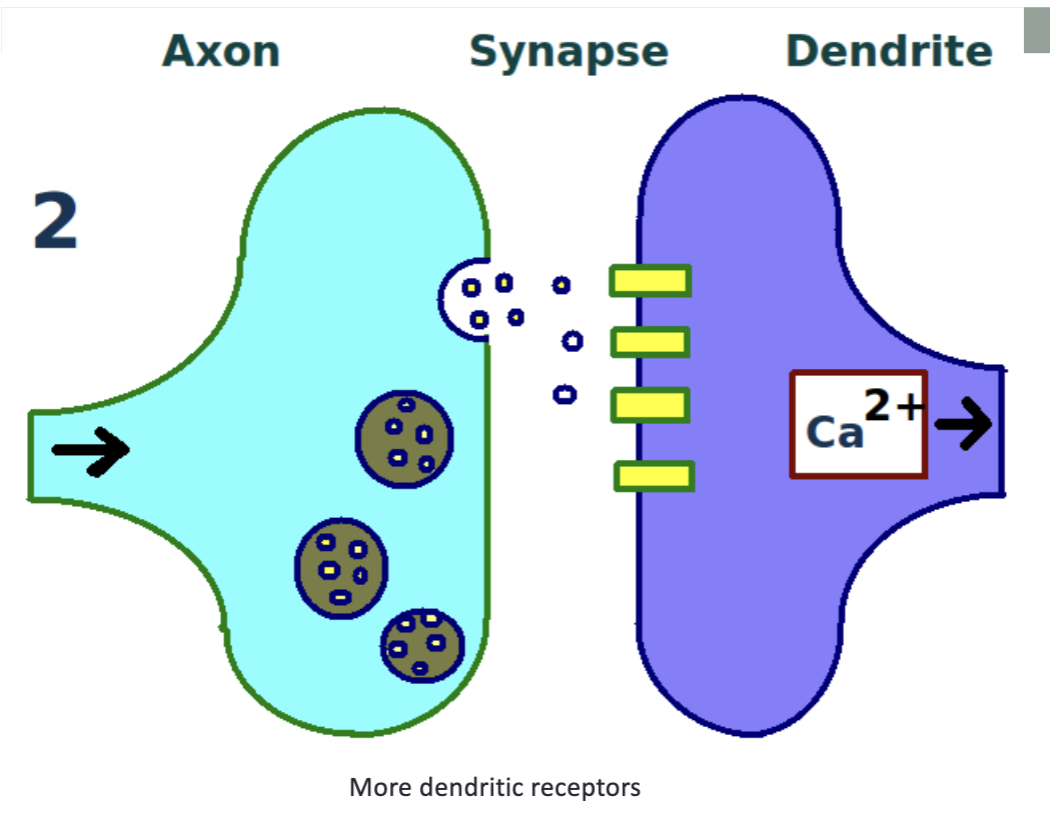

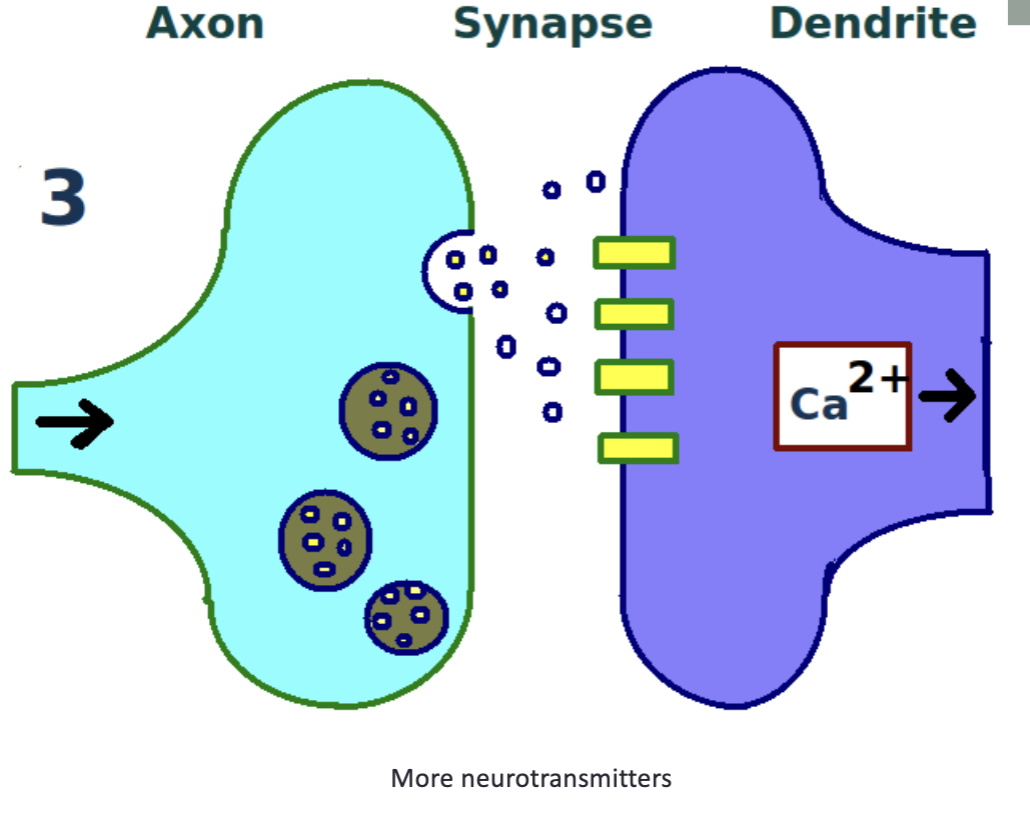

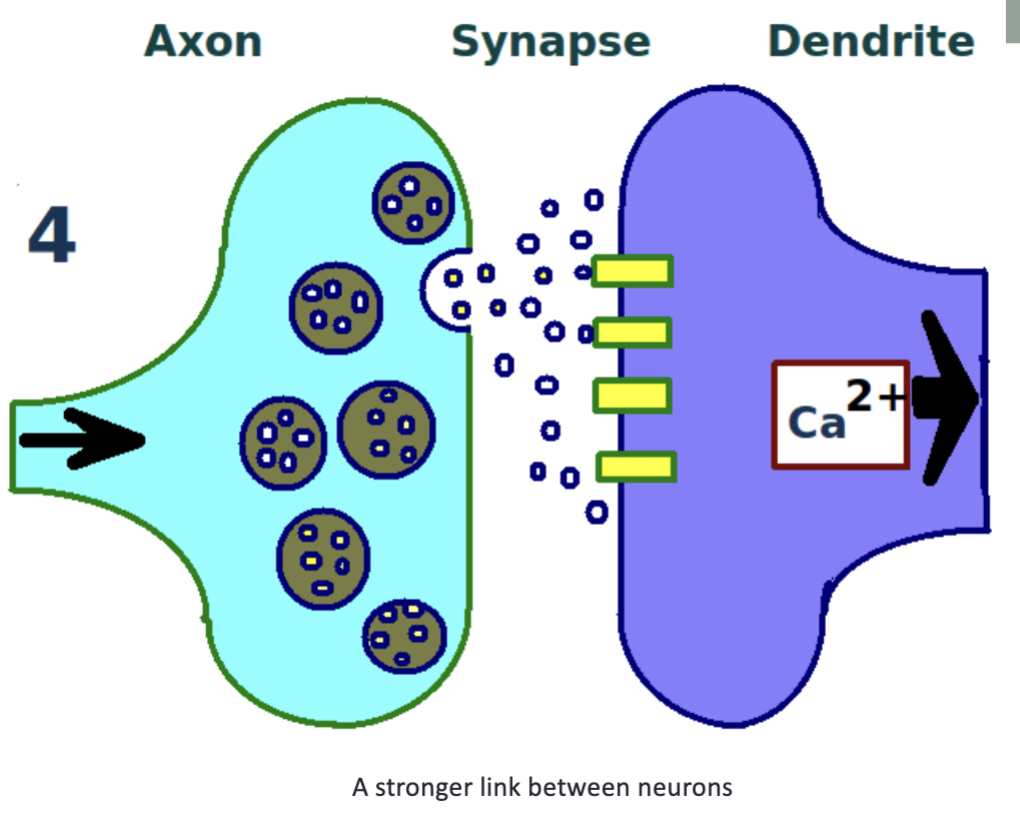

changing information flow

change synaptic strengths

synaptic modification

if based on experience

learning

the consequence

next time- postsynaptic action potential more likely

long-term change in response

learning

“long-term potentiation”

brain structures and cognitive processing

major divisions of the brain

brainstem

hindbrain

rhombencephalon

medulla

pons

cerebellum

midbrain

mesencephalon

tectum

tegmentum

reticular formation

forebrain

prosencephalon

basal ganglia

limbic system

thalamus

hypothalamus

cerebral cortex/neocortex

Methods for Linking Brain & Cognition

A. Brain Imaging

B. Neuropsychology

A. BRAIN IMAGING

Brain Imaging Techniques

Electrical Activity in the Brain

Functional Brain Imaging

ELECTRICAL ACTIVITY

Single-Unit Recording

Focuses on action potentials from individual neurons

Includes components:

Display

Electrode

Stimulus

Electrical Signal from Brain

Overview of Brain Imaging Methods

Examines electrical activity in the context of single-unit recording.

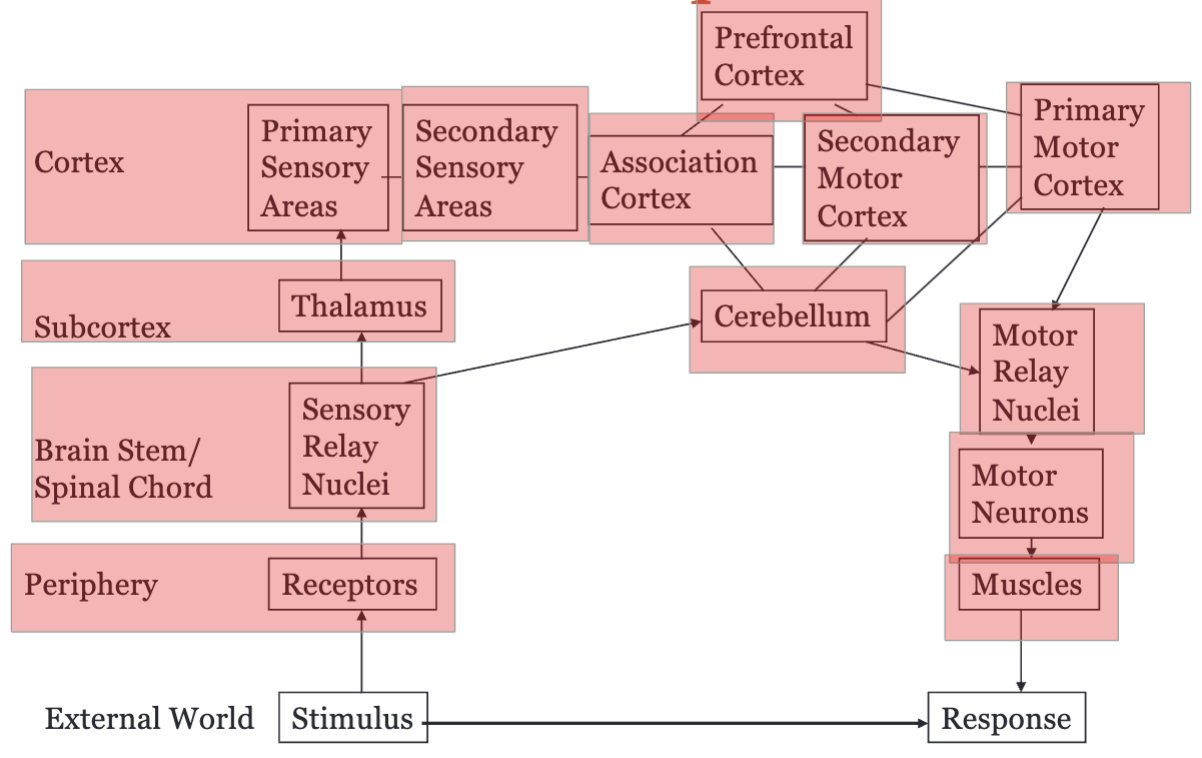

From Stimulus to Response

Process Flow: External World → Stimulus → Response

Involves:

Sensory Relay Nuclei

Thalamus

Receptors

Primary Sensory Areas

Secondary Sensory Areas

Primary Motor Cortex

Association Cortex

Motor Neurons

Single-Unit Recording Details

Examines particular processing within tiny brain regions,

Contrasts with multiunit techniques that look at properties of multiple cells.

Learning Check

Single-cell recording enables understanding the response properties of:

C. One or a relatively small number of neurons at a time

The Electroencephalogram (EEG)

Utilizes scalp electrodes to record voltage fluctuations.

Characteristics of EEG

Not specific to individual neurons;

Records waves generated by neurons;

Weaker signals diminish with distance;

Multiple electrodes help triangulate locations;

Characteristic wave patterns identified.

Learning Check

Which statement is INCORRECT?

B. The invasiveness of EEG recording techniques is the same as that of single and multi-unit recording techniques.

Event-Related Potentials (ERPs)

Overview

Patterns of EEG triggered by a stimulus

Embedded within the overall EEG

Example of ERP

P1, N1, P2, N2, P3

Fluctuations illustrated in an averaged ERP waveform.

Single Unit Recording vs. ERP

Single-Unit Recording: Insight into inner workings, individual neurons' responses.

ERP: Aggregated data, equivalent to crowd noise within a stadium.

ERP Study

Example: Processing Emotion Words

Kissler et al. (2007) study on emotional word responses

High emotional words trigger greater responses 200-300 ms in left occipito-temporal areas.

FUNCTIONAL BRAIN IMAGING

Functional Brain Imaging Key Ideas - 1

Increased brain activity correlates with:

Higher oxygen utilization in blood,

Greater changes in blood oxygen content.

Functional Brain Imaging Key Ideas - 2

Methods:

fMRI: Detects magnetic properties of blood

fNIRS: Tracks optical properties of blood

Functional Brain Imaging Key Ideas - Summary

Measures variations in brain activity through blood flow.

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI)

Description

Relies on the magnetic properties of oxygenated/deoxygenated hemoglobin in blood.

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS)

Based on optical properties of blood's hemoglobin.

Comparing ERPs with fMRI/fNIRS

ERP: Excellent temporal resolution; poor spatial resolution.

fMRI: Good spatial resolution; poor temporal resolution.

fNIRS: Similar to ERP in pros and cons.

Learning Check

fMRI and fNIRS enable imaging of:

B. Blood oxygen changes in the brain.

Learning Check

Which statement is CORRECT?

E. fMRI and fNIRS both utilize differences in the properties of oxygenated vs deoxygenated blood flow.

B. NEUROPSYCHOLOGY

Neuropsychology Overview

Study of cognitive processing in patients with brain injuries or deteriorations.

Causes of Brain Injury/Deterioration

Conditions Leading to Brain Damage:

Blood flow reduction

Cerebrovascular disorders/strokes

Head injuries

Tumors

Infections

Degenerative disorders

First Neuropsychological Finding

1861 Discovery by Paul Broca:

Left frontal damage linked to speech impairment: Broca’s aphasia (expressive aphasia), characterized by halting and effortful speech.

Broca's Area

Identified location linked to speech production responsibilities.

Wernicke’s Aphasia

1874 Discovery by Carl Wernicke:

Damage in the temporal lobe affecting comprehension, resulting in fluent yet nonsensical speech (receptive aphasia).

Importance of Broca and Wernicke

Pioneered studies on language-brain-behavior relations and revealed cognitive consequences of brain lesions.

Other Neuropsychological Examples

Spatial Cognition: Right parietal lobe injury disrupts visual-spatial tasks.

Memory: Hippocampal injury alters specific memory types.

Methods for Linking Brain & Cognition

A. Brain Imaging

B. Neuropsychology

Sensation vs. Perception

Sensation: The process of receiving external stimuli through sensory receptors.

Perception: The cognitive process of interpreting what is sensed, allowing us to understand our environment. This process builds upon the sensory input and elaborates it into a comprehensive interpretation.

Constructivist vs. Ecological Views

Constructivist View: Proposes that perception is constructed through cognitive processes, emphasizing the role of mental interpretation and context.

Ecological View: Suggests that perception is inherently linked to a rich environmental structure that can be processed directly, with both traditional (direct perception with no mental processing) and modern (involving cognitive complexity) perspectives.

Neural Bases of Visual Perception

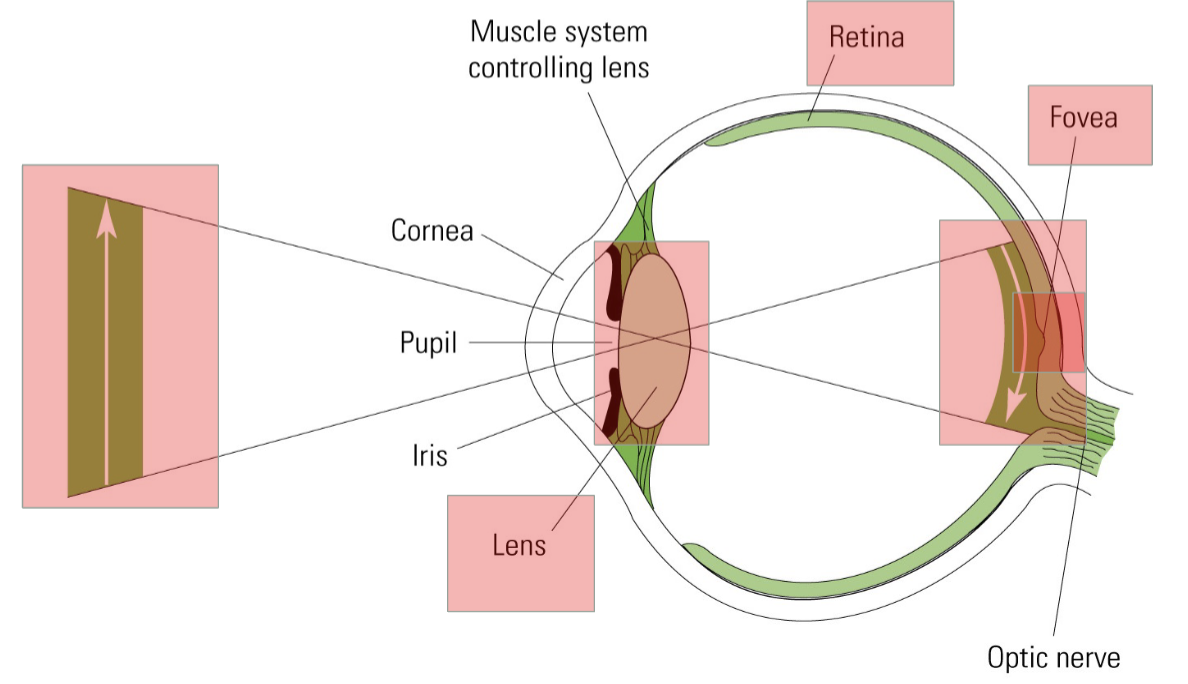

Structure of the Eye

Light enters through the cornea, passes through the pupil (controlled by the iris), and is focused by the lens onto the retina.

The retina contains photoreceptors that convert light into neural signals: cones (for color and detail, primarily located in the fovea) and rods (sensitive to light and motion but color-blind, located in the periphery)

Visual Pathway from Retina to Cortex

Optic Nerve: Transmits visual information from the retina.

Thalamus: Acts as a relay station for sensory information before reaching the cortex.

Primary Visual Cortex (V1): Located in the occipital lobe, responsible for initial visual processing.

Secondary Cortical Areas: Further processing occurs in areas associated with visual perception, with parallel processing pathways identified as the:

Occipital-Parietal Pathway (where): Involved in spatial processing.

Occipital-Temporal Pathway (what): Involved in object recognition.

Organizing the Visual Scene into Objects

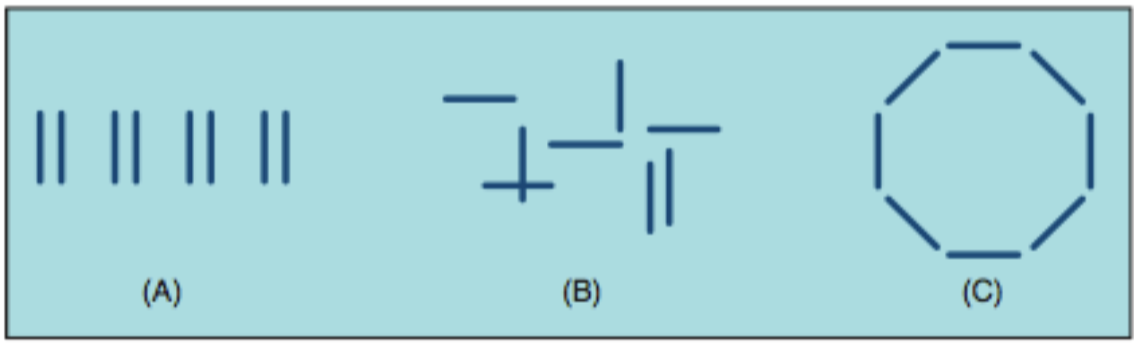

1. Perceptual Grouping

The challenge of organizing visual stimuli into distinct objects involves understanding which elements group together and which do not.

Gestalt Principles: Provide rules on how objects are perceived together, emphasizing higher-level organizational principles:

Pragnanz (Simplicity): Visual inputs are interpreted in the simplest way.

Similarity: Objects that are similar tend to be grouped together.

Parallelism & Symmetry: Shapes that are parallel or symmetrical are likely seen as part of the same object.

Proximity: Closer objects are seen as forming a group.

Common Fate: Objects moving in the same direction are grouped.

2. Figure-Ground Organization

This involves segregating a visual scene into a foreground (figure) and background (ground).

Factors that influence figure-ground assignment include geometric cues such as size, symmetry, and familiarity.

Conclusion

Understanding perception involves unpacking both the physiological foundations and the cognitive processes that allow us to make sense of sensory information. The interplay between sensation and perception, combined with our environment's richness, creates our perception of the world around us.

MODULE 3: PERCEPTION

PART 2

D. VISUAL OBJECT RECOGNITION

Visual object recognition is a fundamental process whereby sensory input is linked to representations stored in memory. The recognition process is complex and there isn’t a definitive single theory that accounts for how we recognize objects; instead, several theories have been proposed to explain this phenomenon.

Theories of Visual Object Recognition

Template Matching

Proposes that the brain compares incoming sensory information to templates stored in memory, looking for a precise match.

Structural-Description Theories

Objects are represented abstractly in terms of their parts and the spatial relations among those parts. Recognition involves creating a structural description of the input and comparing it with existing memory representations.

Feature Analysis/Detection Theories

Focus on the identification of distinct features within a visual input and the comparison of these features with stored descriptions in memory.

Recognition-by-Components

Developed by Irving Biederman, this theory suggests that objects are recognized by the geons (geometric icons) that make them up.

View-Based Theories

These theories assert that object recognition is dependent on specific views or perspectives of an object, with multiple angles stored in memory for comparison.

Template Example in Object Recognition

Examples illustrate how different templates may correlate with various objects. For instance:

A strong correlation (100%) means an exact match with stored templates, while a weak correlation (30%) indicates a lesser similarity.

Structural-Description Theories in Detail

Recognition involves forming a structural description and comparing it with memory to identify the possible parts of the object and how they can be recognized.

Different theories propose different sets of parts that can complicate recognition.

Featural Analysis in Object Recognition

This approach analyzes incoming visual images by breaking them down into features, which are then compared with stored descriptions. For example, components like vertical and horizontal lines can help define objects.

Recognition-By-Components Theory

This is a renowned structural description theory that suggests we identify objects based on their components known as geons. Geons are simple geometric shapes that serve as the building blocks of objects.

Types of Geons

Some commonly identified geons include:

Wedges

Bricks

Cubes

Cylinders

ConesThese shapes possess significant properties that aid in object recognition.

Properties of Geons

Viewpoint Invariance

Geons remain recognizable from various angles and are sturdy against visual noise.

Robustness to Occlusion

Geons can still be recognized even when partially obscured. For instance, concave regions are critical cues for identifying an object.

Discriminability

This is associated with nonaccidental properties that remain consistent despite changes in the viewpoint. Examples include specific edges, vertices, and parallel lines that help in object identification.

Human and Animal Recognition Studies

Research comparing nonaccidental properties in humans and pigeons reveals that structural cueing plays a critical role across different species, showing the biological basis of visual recognition capabilities.

Stages in Recognition-by-Components Theory

Detection of Nonaccidental Properties

Edge Extraction

Determination of Components

Parsing at Regions of Concavity

Matching of Components to Object Representations

Object IdentificationThese stages highlight the cognitive processes involved in perceiving and identifying objects.

Challenges of Structural Description Accounts

Structural description theories may face challenges, such as instances where the same object's representation differs dramatically depending on the viewpoint (e.g., a book vs. a cigar box).

View-Based Theories

While geons are significant, recognition can also be highly viewpoint-dependent. It’s suggested that the brain may store only a few specific views of an object and utilizes mental rotation to comprehend them from different angles.

Example of View-Based Theories

The example provided by Yanagi illustrates performance in categorizing objects based on specific views and size comparisons.

Summary

Visual recognition is enshrined in the debate between structural-description theories, like recognition-by-components, and view-based theories. Each approach sheds light on different aspects of perception, and ongoing discourse continues to explore newer models that integrate ecological and constructivist perspectives. This discourse emphasizes the rich details within stimuli and the capacity for learning from diverse exposures, aided by complex neural network models.