Untitled Flashcards Set

Week 1: cap 1,2,3

Cap 1:

· why is it important to understand social research methods?

1. To prevent and avoid some errors and difficulties that may arise when conducting social research.

2. Being aware of the full range of methods and approaches available to you.

3. Help understand the research methods used in the published work of others.

· What is social research?

· Academic research conducted by social scientists from a broad range of disciplines such as sociology, anthropology, education, human geography, social policy, politics and criminology.

· What is motivated by?

· Developments in changes and society

· It is essential for generating new knowledge and expanding our understanding of contemporary social life.

· Research methods= tools and techniques that social scientists use to explore different topics. A research method is a tool, such as a survey, an interview, or a focus group, that a researcher uses to explore an area of interest by gathering information (data) that they then analyze.

· Methodology= refers the broader and the overall approach being taken in the research project and the reasoning behind the research method.

1. Why do social research?

2. Noticing a gap in academic literature

3. Noticing inconsistency in preexisting literature

4. Understanding what is going on in society that is unresolved

· Social research and its methods are influenced by various contextual factors and do not occur in isolation:

a) theory, and researchers’ viewpoints on its role in research;

b) the existing research literature;

c) epistemological and ontological questions;

d) values, ethics, and politics.

a) Theory and researcher’s viewpoint’s role in research: ‘ideas and intellectual traditions’ often refers about theories.

Theory= a group of ideas that aims to explain something, in this case the social world.

Theories have significant influence on the research topic being investigated, both in terms of what is studied and how findings are interpreted. As well as influencing social research, theories can themselves be influenced by it, because the findings of a study add to the knowledge base to which the theory relates.

Researcher’s views about the nature of the theory can have implications for research. For instance, choosing quantitative research and qualitative research has implication for the research: quantitative is based in hypothesis and theoretical ideas which drive the collection and analysis of data while qualitative suggest a more open-ended strategy in which theoretical ideas emerge out of the data.

b) Existing knowledge: the existing knowledge in the area in which a researcher is interested also forms an important part of the background against which social research takes place. It is then necessary being familiar with the literature on the topic investigated to build and avoid repeating work already done.

c) Epistemological and ontological questions: views about how knowledge should be produced are known as epistemological positions which raise questions about how the social world should be studied and whether the scientific approach advocated by some researchers is the right one for social research.

The views about the nature of the social world and social phenomena are known as ontological positions. Debating whether social phenomena are relatively inert and beyond our influence or are a product of social interaction.

The stance taken on both issues has implications for the way social research is conducted.

d) Values, ethics and politics:

1. Ethical Considerations:

Ethical issues are central to social research and have become more critical with new data sources like social media.

Researchers must typically undergo a process of ethical clearance, especially when involving vulnerable populations (e.g., children).

Participant Involvement:

In fields like social policy, there's a strong belief that research participants, especially service users, should be involved in the research process.

This involvement can include formulating research questions and designing instruments such as questionnaires.

The collaborative approach is often referred to as “co-production.”

Political Context:

Social research is influenced by political factors, including government funding priorities, which can shape which research topics receive support.

The political landscape also affects access to research settings and the dynamics of research teams.

Wider Context Influence:

The choices of research methods and the focus of social research are closely related to broader contextual factors, including ethical standards, participant empowerment, and political considerations.

These aspects underscore the interconnectedness of values, ethics, and the political landscape in shaping social research practices and outcomes.

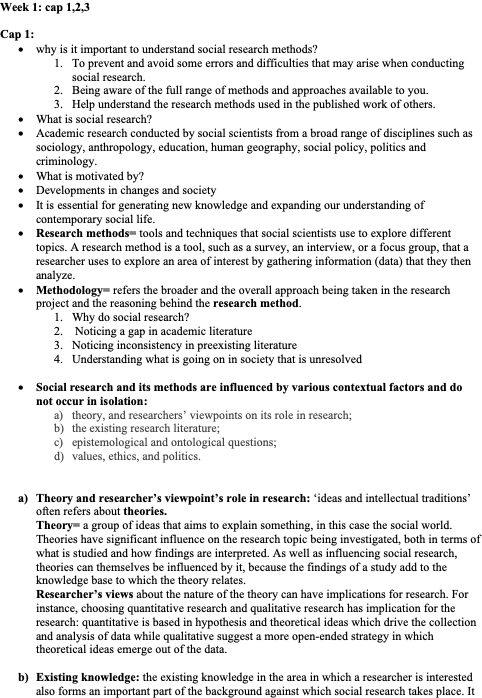

The main elements of social research:

The main stages of most research projects

Literature review

| A critical examination of existing research that relates to the phenomena of interest, and of relevant theoretical ideas.

|

Concepts and theories

| The ideas that drive the research process and that help researchers interpret their findings. In the course of the study, the findings also contribute to the ideas that the researchers are examining.

|

Research question(s)

| A question or questions providing an explicit statement of what the researcher wants to know about.

|

Sampling cases

| The selection of cases (often people, but not always) that are relevant to the research questions.

|

Data collection

| Gathering data from the sample with the aim of providing answers to the research questions.

|

Data analysis

| The management, analysis, and interpretation of the data.

|

Writing up

| Dissemination of the research and its findings

|

1. Literature review= need to explore what has already been written about it in order to determine:

• what is already known about the topic;

• what concepts and theories have been applied to the topic;

• what research methods have been applied to the topic;

• what controversies exist about the topic and how it is studied;

• what contradictions of evidence (if any) exist;

• who the key contributors are to research on the topic;

• what the implications of the literature are for our own research.

It is difficult to read all existing literature, but the main books and articles need to be read. After in the research paper this knowledge is shared with future readers by writing the literature review and it must be critical than merely descriptive.

2. Concepts and theories= Concepts are labels we use to understand and categorize aspects of the social world that share common features. They help us make sense of complex social phenomena. Examples of key concepts in social sciences include bureaucracy, power, social control, status, hegemony, and alienation. These concepts are fundamental to the development of theories in social research.

Role of Concepts:

Concepts play a crucial role in organizing research interests and communicating them to intended audiences.

They encourage researchers to reflect on their investigative focus and provide a framework for organizing research findings.

Theoretical Frameworks:

Concepts are integral to theories, serving as foundational elements that shape research questions and methodologies.

The relationship between theory and research can be viewed through two lenses:

Deductive Approach: Theories drive the research process, guiding data collection and analysis based on predefined concepts.

Inductive Approach: Concepts emerge from the research process, helping to organize and reflect on data as it is collected.

Dynamic Nature of Concepts:

The boundary between deductive and inductive approaches is not rigid; researchers often begin with key concepts to guide their studies but may revise or develop new concepts based on their findings and interpretations.

This iterative process emphasizes the fluidity of concepts as they adapt to the realities uncovered during research.

Importance of Literature:

Familiarity with existing literature is essential as it reveals established concepts and their effectiveness in addressing key research questions.

3. Research questions= explicit statements of what is intended to find about. There are several advantages of having a research question:

• guide your literature search;

• guide your decisions about the kind of research design to use;

• guide your decisions about what data to collect and from whom;

• guide the analysis of your data;

• guide the writing up of your data;

• stop you from going off in unnecessary directions; and

• provide your readers with a clear sense of what your research is about.

Reading additional literature will prompt revisitation of research questions or creation of new ones.

à Influence of Research Questions:

o The nature of the research question is crucial in determining the approach to the investigation and the choice of research design.

à Types of Research Designs:

o Experimental Design: Suitable for assessing the impact of an intervention.

o Longitudinal Design: Appropriate for studying social change over time, allowing for observations across different time points.

o Case Study Design: Useful when focusing on specific communities, organizations, or groups, providing in-depth insights.

o Cross-Sectional Design: Ideal for capturing current attitudes or behaviors at a single point in time, offering a snapshot view.

o Comparative Element: If the research question involves comparison, the design will need to reflect this aspect.

à Familiarity with Research Designs:

o Researchers must understand the implications and suitability of different research designs in relation to their specific questions, as each design supports different types of inquiries and outcomes.

à Sampling= it is impossible to include all individuals who would fits the research hence researchers aim to secure a sample that represents a wider population by effectively replicating it in miniature. Sampling does not only apply to survey research but also content analysis and other research strategy.

à Data collection= Data collection is considered a crucial aspect of research, often discussed in detail due to its significance in the research process. It can be approached in two main ways: structured and flexible. Structured methods, such as self-completion questionnaires and structured interviews, involve a predetermined approach where researchers define what they want to learn and design data collection tools accordingly. These methods align with a deductive approach to research, focusing on testing specific hypotheses. In contrast, flexible methods emphasize a more open-ended approach, allowing researchers to adapt their focus as new data emerges. Techniques such as participant observation and semi-structured interviews facilitate inductive theorizing, where concepts and theories evolve from the data rather than being predefined. While flexible methods still aim to address research questions, these may not always be explicitly stated, reflecting the exploratory nature of the research. Overall, this section underscores the variety of approaches researchers can take in data collection based on their objectives, highlighting its central role in the research process.

à Data analysis= it involves applying statistical techniques to data that have been collected. There are multiple aspects to data analysis which are managing the raw data, making sense of the data, interpreting the data.

a) Managing data: This stage includes checking for errors to ensure accuracy. In qualitative research, audio recordings of interviews are transcribed, requiring attention to detail to avoid misinterpretation. In quantitative studies, survey data is either inputted from paper forms or downloaded into analysis software like SPSS or Excel.

b) Data reduction: Data reduction condenses large volumes of information to facilitate interpretation. Qualitative analysis involves coding data into themes, while quantitative analysis may address anomalies like missing responses.

c) Primary and secondary analysis: After managing and analyzing the data, researchers link their findings back to research questions and relevant literature to draw meaningful conclusions. Primary Analysis involves researchers analyzing data they collected themselves, while Secondary Analysis refers to analyzing existing data. Secondary analysis is efficient and cost-effective, allowing researchers to explore new questions without the extensive process of data collection.

à Writing up: research is of no use if it is not written up and it is not shared with others.

Format

Introduction. This outlines the research area and its significance. It may also introduce the research questions.

• Literature review. This sets out what is already known about the research area and examines it critically.

• Research methods. The researcher presents the research methods that they used (sampling strategy, methods of data collection, methods of data analysis) and justifies the choice of methods.

• Results. The researcher presents their findings.

• Discussion. This examines the implications of the findings in relation to the literature and the research questions.

• Conclusion. This emphasizes the significance of the research.

The messiness of research:

Realities of Social Research:

The book aims to present a clear, accessible view of social research while acknowledging that the process is often less straightforward than it appears in academic literature. Research frequently involves false starts, mistakes, and necessary changes to plans.

Research Challenges:

Many potential issues cannot be anticipated because they are unique, one-off events. While some reports suggest smooth research processes, they often omit the challenges faced, focusing instead on what was achieved.

Reflexivity and Reporting:

Researchers typically acknowledge limitations in their studies, but academic reports usually highlight successful findings rather than detailing difficulties. This tendency is common across disciplines, including natural sciences.

Acknowledging Messiness:

Recognizing the complexities and imperfections in social research does not devalue it; rather, it is essential for transparency and rigor. Acknowledging weaknesses helps improve methods and reassures novice researchers that messiness is a normal aspect of real-world research.

Reflective Writing:

Researchers are encouraged to reflect on challenges and limitations in their projects. By documenting what was planned versus what actually occurred, they demonstrate an understanding of the implications of any changes made during the research.

Methodological Diversity:

Social research includes various methodological traditions that may conflict, which fosters justification for decisions and critical thinking about research objectives. The distinctions between quantitative and qualitative approaches are often less clear than they appear.

Complexity of the Social World:

The intricate and messy nature of the social world is what makes it fascinating to study. The following chapters will explore different perspectives and principles of research methodology, providing foundational theoretical knowledge and guidance for conducting research.

Cap 2: social research strategies, quantitative research and qualitative research

What is empiricism? Empiricism is a term that has multiple meanings, but it is primarily defined in two ways:

General approach to reality: Empiricism suggests that knowledge is valid only if it is gained through experience and the senses. This perspective holds that ideas must undergo rigorous testing to be considered knowledge.

Belief in facts: The second meaning of empiricism emphasizes that acquiring facts is a legitimate goal in its own right. This is sometimes referred to as "naive empiricism," which highlights the importance of collecting descriptive data, such as in a national census, to understand demographic changes and inform social research and government policies

Research in the social sciences is driven by various motivations, but theory plays a crucial role in enhancing our understanding of knowledge. It is essential to reflect on the connection between theory and research, particularly regarding the philosophical assumptions about the roles of theory and data. This reflection influences research design, the formulation of research questions, and the choice between qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods for data collection.

Link between theory and research:

Understanding the relationship between theory and research is complex, influenced by the type of theory being used and the approach to data collection (deductive vs. inductive).

Definition of theory:

The term "theory" generally refers to explanations for observed patterns or events, often framed in broader theoretical contexts such as structural functionalism or symbolic interactionism.

2 types of Theories:

1. Middle-Range theories: Developed by Merton, these theories focus on specific aspects of social phenomena and are more useful for empirical research. Examples include labelling theory and differential association theory.

2. Grand theories: These are more abstract and provide limited practical guidance for research, making it challenging to apply them to real-world situations.

Role of background literature:

Background literature can function as a substitute for theory, helping to inform research questions and guiding the research process. Researchers may use existing literature to identify gaps or inconsistencies that warrant further investigation.

Skepticism towards naive empiricism:

Research lacking clear theoretical connections may be dismissed as naive empiricism. However, studies using relevant background literature as a theoretical foundation are valid and important.

Dynamic relationship between theory and data:

While theory typically guides data collection and analysis, it can also emerge after the research process. This distinction leads to the concepts of deductive (theory-driven) and inductive (data-driven) approaches to research.

Definitions:

Middle-Range theories: Focus on specific social phenomena; useful for empirical inquiry.

Grand theories: Abstract theories with limited applicability to specific research.

Naive empiricism: Dismissal of research that appears to lack theoretical grounding.

Deductive approach: Data collection guided by existing theories.

Inductive approach: Theories developed based on data analysis.

Deductive vs Inductive approach:

Deductive approach:

The deductive approach is a research methodology where the researcher utilizes existing knowledge and relevant theoretical ideas to formulate a hypothesis (or hypotheses) that can be tested empirically. Key aspects of the deductive approach include:

Hypothesis development:

The researcher starts with established theories and draws specific hypotheses from them. These hypotheses are speculative statements that the researcher aims to test.

Researchable entities:

The concepts within the hypothesis need to be translated into researchable entities, often referred to as variables. This involves determining how these concepts can be operationalized for empirical investigation.

Data collection:

Developing a hypothesis includes planning how data will be collected on each variable, ensuring that the research can effectively test the hypothesis.

Quantitative research preference:

The deductive approach is more commonly associated with quantitative research, where the language of hypotheses, variables, and empirical testing is prevalent. This approach is less applicable to qualitative research.

Role of middle-range theories:

Merton’s concept of middle-range theories is pertinent here, as these theories are primarily used to guide empirical inquiry within sociology, forming a foundation for the deductive process.

Sequence of events:

In a deductive research project, the process begins with theory and hypothesis formulation, which then drives data gathering. This process is sequential and logical.

Revision of theory:

After data collection and analysis, researchers reflect on their findings, which may lead to the revision of the original theory. This reflective process involves an inductive aspect, where new insights are integrated back into the existing body of knowledge.

Important points

Hypothesis: A testable speculation derived from theoretical frameworks.

Variables: Operationalized concepts that allow for empirical testing.

Quantitative focus: The deductive approach is primarily used in quantitative research.

Middle-Range theories: Theories that guide empirical research in specific areas of sociology.

Inductive reflection: The process of revising theories based on new findings, integrating both deductive and inductive reasoning.

Not all deductive research projects strictly follow the expected sequence of deriving hypotheses from theory. The term "theory" can also refer to the existing literature on a topic, rather than just specific theoretical frameworks. Additionally, researchers’ perspectives on theory or literature may evolve during the data analysis phase, and new theoretical ideas can emerge after data collection is completed. The typical logic of research involves developing theories and subsequently testing them; however, the practical application of this logic varies across different studies. Therefore, while the deductive process exists, it should be viewed as a general framework rather than a rigid model applicable to all research.

Inductive approach:

The inductive approach is a research methodology that focuses on deriving theory from empirical observations rather than starting with existing theories. Key aspects of the inductive approach include:

Theory development:

In the inductive approach, theory emerges as the outcome of research, formed by drawing generalizable inferences from observations. Researchers do not begin with a hypothesis but rather develop one based on their findings.

Linking theory and research:

Induction provides an alternative strategy for connecting theory and research, contrasting with the deductive approach where theory guides the research process.

Iterative strategy:

The inductive process often involves an iterative strategy, where researchers move back and forth between data collection and theory refinement. This allows for adjustments based on ongoing analysis.

Combination of approaches:

While primarily inductive, this approach may still involve some deductive elements, particularly when researchers reflect on collected data and determine conditions under which a theory may hold.

Grounded theory:

An example of the inductive approach is the grounded theory method, as used in O'Reilly et al. (2012). This method focuses on generating theory directly from qualitative data, emphasizing the significance of the findings derived from the analysis.

Qualitative focus:

The inductive approach is often associated with qualitative research, which allows for a deeper exploration of the data and the emergence of new theoretical insights.

Important points

Emergent Theory: Theory is developed from data rather than imposed beforehand.

Observations: The approach relies heavily on empirical observations to inform theoretical frameworks.

Iterative Nature: Emphasizes a back-and-forth process between data collection and theoretical development.

Grounded Theory: A specific method within the inductive approach that generates theory from qualitative data.

However:

· These distinctions are not as straightforward as they are sometimes presented, it is best to think of them as tendencies rather than fixed distinctions. In fact there is also a 3 approach called abductive reasoning.

Abductive Reasoning: Abductive reasoning is a logical approach that begins with an observation or a puzzling phenomenon and seeks to explain it by identifying the most likely explanation. This process involves a back-and-forth movement between the observed data (the puzzle) and the broader social context or existing literature, often referred to as dialectical shuttling. Abduction acknowledges that the conclusions drawn from observations are plausible but not entirely certain, as there may be multiple explanations for the same observation. For example, if you notice smoke in your kitchen, abductive reasoning would lead you to infer that the most probable cause is that you burned dinner, while also considering other possible explanations, like smoke from outside.

Adduction: Adduction is often used interchangeably with abductive reasoning, emphasizing the inference to the best explanation based on available evidence. It focuses on the process of reasoning that connects observations to theories or explanations, aiming to provide the most plausible interpretation of the data at hand. Adduction involves synthesizing information from observations and existing knowledge to generate a reasonable hypothesis or explanation that can be further explored.

Key aspects

Abductive Reasoning: Begins with observations to explain them using the most likely explanations, acknowledging the plausibility but not certainty of conclusions.

Adduction: Similar to abduction, it focuses on synthesizing observations and existing theories to infer the best explanation for a phenomenon.

Epistemogical considerations:

Epistemogical issues concern the question of what it should be studied according to the same principles, procedures, and ethos as the natural sciences.

The argument that social sciences should imitate the natural science is associated with epistemogical position of Positivism.

Positivism is an epistemological stance advocating for the use of natural science methodologies in the study of social reality and other domains. It emphasizes the reliance on empirical evidence and seeks to create objective, law-like knowledge similar to the natural sciences. Here is an explanation of the characteristics of positivism:

Phenomenalism: Positivism holds that only phenomena observable and verifiable through the senses qualify as genuine knowledge. This implies that abstract concepts or theoretical ideas must be anchored in empirical evidence to be meaningful.

Deductivism: Positivist theory aims to formulate hypotheses that can be empirically tested. These hypotheses are used to assess patterns, regularities, and laws governing social reality. Thus, positivism emphasizes a scientific approach where theories are tested through systematic observation and experimentation.

Inductivism: Knowledge, according to positivism, is accumulated through gathering empirical facts, which then form the foundation for identifying and establishing general laws. This means that broad theories or principles are derived from the careful analysis of factual data.

Objectivity and Value-Free Science: Positivism insists on objectivity in scientific research. Scientific inquiry must be conducted without bias or the influence of the researcher’s values, beliefs, or personal preferences. The results of such studies should be independent of the researcher’s subjective interpretations.

Separation of Scientific and Normative Statements: Positivism differentiates between a)descriptive scientific statements (which are objective and can be proven through empirical evidence) and b)normative statements (which reflect value judgments and cannot be empirically verified). A positivist approach prioritizes scientific statements over normative ones, emphasizing that science should remain neutral and not engage in ethical or moral evaluations.

For some researcher this doctrine is a descriptive category for other it has a negative connotation since it describes crudely and superficial practices of data collection.

Positivism includes both aspects of deductive and inductive approach. It is also very sharp on the distinction between theory and research and with the role of the researcher being to test theories and to provide material for the developments of laws. In fact, it implies that it is possible to collect observations that is not influenced by pre-existing theories.

Another similar stance is realism:

Realism is an epistemological and philosophical position that asserts the existence of an external reality that exists independently of our perception or description of it. Realism emphasizes that the natural and social worlds are governed by structures and mechanisms that can be studied using appropriate scientific methods.

Similarities with positivism:

Use of scientific methods: Both realism and positivism believe that the natural and social sciences can and should use similar scientific methods for collecting data and developing explanations. This reflects a shared commitment to systematic, empirical investigation.

Belief in an external reality: Both approaches maintain that there is an external reality independent of human perception or description. They argue that science should focus on uncovering and explaining this objective reality.

Types of realism:

Empirical realism (or Naive realism):

Definition: This form of realism posits that reality can be comprehended through the application of suitable empirical methods. It assumes that there is a direct or nearly perfect correspondence between the terms we use to describe the world and the actual world itself.

Criticism: Critics argue that empirical realism overlooks the underlying structures and generative mechanisms that produce observable phenomena. It is considered "superficial" because it focuses only on what can be directly observed and fails to acknowledge deeper causal forces at play.

Critical realism:

Definition: Critical realism, developed by philosopher Roy Bhaskar, recognizes both the reality of the natural world and the events and discourses of the social world. It contends that to truly understand and potentially change the social world, one must identify and analyze the underlying structures and mechanisms that generate observable events.

Key Concepts:

Critical realism emphasizes that these structures are not immediately apparent in observable patterns. Instead, they require detailed theoretical and practical investigation to be identified.

Critical realists accept that our scientific descriptions of reality do not perfectly mirror reality itself. Rather, they view scientific theories as tools for understanding and explaining underlying causal mechanisms.

Unlike positivism, critical realism is open to using theoretical constructs that may not be directly observable but are essential for explaining how observable phenomena occur.

And in summary:

Realism focuses on the belief in an objective reality and supports the application of scientific methods to understand it.

Empirical Realism is criticized for being overly simplistic, assuming a direct correspondence between observations and reality.

Critical Realism takes a deeper approach, arguing that reality involves structures and mechanisms not immediately visible but essential for understanding and transforming the world. Critical realism emphasizes the importance of theoretical work in uncovering these deeper forces.

An epistemology that contrasts with positivism is Interpretivism:

Interpretivism is an epistemological perspective that serves as an alternative to positivism in the social sciences. It holds that the study of human behavior requires different research methods from those used in the natural sciences because people, unlike natural objects, have subjective experiences and interpretations that influence their actions.

Fundamental differences between people and natural objects: Interpretivism emphasizes that human beings are fundamentally different from the objects studied in the natural sciences. Humans have thoughts, feelings, and intentions that shape their actions, making the study of human behavior more complex and requiring a more nuanced approach.

Need for distinct research methods: Because of these differences, interpretivism argues that social scientists must use research methods that can capture and understand the subjective experiences and meanings of human actions. These methods focus on understanding the ways individuals interpret and make sense of their world.

Understanding subjective experience: Interpretivist research seeks to grasp the subjective meanings and experiences of social actions. This involves understanding what social experiences mean in practice, how they are perceived by individuals and groups, and the reasons behind these interpretations.

Intellectual influences:

a) Weber’s Idea of Verstehen: This concept emphasizes understanding social action by placing oneself in the position of the people being studied to interpret their actions and motivations.

b) Hermeneutic–Phenomenological Tradition: This tradition focuses on the interpretation and meaning of human experiences, often emphasizing the importance of context and the lived experience.

c) Symbolic Interactionism: This theory explores how individuals create and interpret meanings through social interaction, emphasizing the importance of symbols and language in shaping human behavior.

A. Weber’s Idea of Verstehen: This concept emphasizes understanding social action by placing oneself in the position of the people being studied to interpret their actions and motivations.

Hermeneutics and Verstehen are both central concepts within interpretivism, influencing how social scientists approach the understanding of human actions and experiences.

Hermeneutics:

Definition: Hermeneutics originated in theology, where it was used to interpret religious texts. In the social sciences, hermeneutics has evolved into a broader theory and method concerned with the interpretation and understanding of human action.

Focus: Hermeneutics emphasizes how understanding is shaped by historical, cultural, and linguistic contexts. It is not just about observing actions but about interpreting the meaning behind them in a way that accounts for the environment in which those actions occur.

Core Ideas:

Situated understanding: Hermeneutics posits that human understanding is always "situated," meaning it cannot be fully detached from the context in which people live and interact. Humans are not passive entities shaped only by external social forces; they actively interpret and create meaning based on their experiences.

Contrast with Positivism: Hermeneutics challenges the positivist approach of explaining human behavior through general laws and instead focuses on understanding the subjective meanings behind social actions. It acknowledges that human actions are driven by complex motivations and interpretations that cannot always be simplified into abstract, law-like generalizations.

Verstehen:

Definition: Verstehen is a German term meaning "understanding," introduced and popularized by sociologist Max Weber. It refers to the interpretive understanding of social action.

Weber's Perspective: Weber argued that the purpose of the social sciences is to comprehend how individuals perceive and act in their social world. He emphasized that sociology should not just seek causal explanations but should aim to understand the meanings and motives behind people’s actions from their own perspective.

Interpretive approach:

Weber's method involves placing oneself in the position of others to interpret their actions and the social conditions that give rise to those actions. This involves looking at the intentions, beliefs, and contexts that shape behavior, rather than attributing human actions to overarching social forces.

Example: In contrast to Émile Durkheim’s positivist approach, which explained suicide rates through social integration levels, Jack D. Douglas (working in the Weberian tradition) emphasized the subjective and situational interpretations of suicide. He argued that understanding suicide involves examining how coroners interpret deaths and recognizing that meanings of suicide differ across contexts.

Summary:

Hermeneutics focuses on interpreting human action by considering the influence of history, culture, and language, emphasizing that understanding is context dependent.

Verstehen, as developed by Weber, stresses the need for interpretive understanding in the social sciences to grasp the subjective meanings and motivations behind social actions.

Both concepts challenge positivist approaches that seek to explain behavior through universal laws, emphasizing the complexity and situational nature of human understanding and action.

B. Hermeneutic–Phenomenological Tradition:

phenomenology is a philosophical approach that significantly contributes to the interpretivist position, opposing positivist methodologies in the social sciences. It focuses on understanding how individuals perceive and make sense of the world around them, emphasizing that researchers must become aware of and attempt to overcome their preconceptions to understand the subjective experiences and consciousness of others.

Core concepts of phenomenology:

Human Consciousness and Experience: Phenomenology emphasizes how human beings experience the world and attribute meaning to those experiences. It suggests that reality is constructed through the perceptions and interpretations of individuals. Therefore, to truly understand social phenomena, one must consider the perspectives and meanings held by the people who experience them.

Origins and Key Figures:

The philosophical roots of phenomenology trace back to Edmund Husserl, who emphasized the study of consciousness and the meanings that individuals attach to their experiences.

Alfred Schutz applied Husserl’s phenomenological ideas to the social sciences, integrating Max Weber’s concept of Verstehen (understanding). Schutz's work emphasized interpreting social reality by understanding the meanings that people give to their everyday experiences.

The two key points from Schutz’s quote are (p 126):

The distinction between the natural and social sciences, highlighting that social reality is meaningful and must be studied differently from natural phenomena.

The importance of understanding and interpreting people’s “common-sense thinking” to comprehend their actions, emphasizing the need for an empathetic, perspective-taking approach to social research.

C. Symbolic interactionism:

Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic Interactionism, developed by George Herbert Mead and expanded by Herbert Blumer, is a sociological framework focusing on how individuals interpret and act based on symbolic meanings. These meanings are constructed and continuously reshaped through social interactions.

Core concepts:

Meaning and symbols: People give meaning to objects, actions, and symbols through interaction. These meanings are not inherent but created through communication.

Interpretation of actions: Behavior is guided by the meanings people assign to their environment and the actions of others, which they actively interpret.

Social construction of Self: The concept of the "looking-glass self" explains how our sense of self develops from how we think others perceive us.

Influence on Interpretivism

Symbolic interactionism reinforces interpretivism’s focus on understanding human actions from the actor’s perspective:

Subjective Meaning: Both emphasize interpreting the meanings individuals give to their experiences.

Social Interaction: Symbolic interactionism highlights how meanings are created through interaction, aligning with interpretivism’s view of behavior as socially and contextually shaped.

Blumer’s contribution: Herbert Blumer emphasized the importance of understanding how people interpret their actions, reinforcing the interpretive approach.

Distinction from Hermeneutic–Phenomenological tradition

Symbolic Interactionism: A theory centered on how people use symbols in interaction, guiding researchers to study communication and meaning making.

Hermeneutic–Phenomenological Tradition: A broader approach focusing on understanding human experiences within cultural and historical contexts.

The Process of interpretation and ‘Double Hermeneutic’:

In interpretivist research, interpretation involves understanding how members of a social group make sense of their world and then framing these interpretations within a social-scientific context. This results in what is called a double hermeneutic: a two-layered interpretation process where the researcher interprets the interpretations of the people they are studying.

First Level: The social scientist gathers data and interprets how the participants understand their world, capturing the meanings and perspectives within the social context of the participants.

Second Level: The researcher then places these interpretations into a broader scientific framework, analyzing and contextualizing them using theoretical concepts and existing literature.

The double hermeneutic highlights the complexity of social research and the need for reflexivity—where researchers critically examine their assumptions and biases throughout the research process. Researchers must be explicit about their choices in research design and analysis to increase awareness of how their perspectives influence the study.

Ontological considerations:

Ontology: the study of being, social ontology is about the nature of social entities, such as organizations and culture. the researcher’s ontological stance determine how reality is defined.

Key for social scientist is whether social entities can and should be considered as:

a) Objective entities that exist separately so social actors or people

b) Social constructions that have been and continue to be built up from the perceptions and actions of social actors.

2 main positions referred as objectivism and constructionism:

1) Objectivism: is an ontological position that claims that social phenomena, their meanings, and the categories that we use in everyday discourse have an existence that is independent of, or separate from, social actors.

In objectivism, both organizations and cultures are conceptualized as external realities that exert influence on individuals. They are treated as almost tangible, objective entities that exist independently of social actors, with rules, values, and structures that people must learn, internalize, and follow. This perspective emphasizes the constraining and regulating effect these social phenomena have on individual behavior.

2) Constructionism:

Constructionism (or constructivism) is an ontological stance that argues social phenomena and their meanings are continually created and shaped through social interaction. It holds that social realities are not fixed or independent but are constantly constructed and revised by people.

Key points of constructionism:

Social phenomena as constructed: Social phenomena do not exist independently of human interaction. Instead, they are actively created and redefined through social processes. This means that what we understand as reality is fluid, evolving as individuals and groups continuously engage and reinterpret their social worlds.

Constant state of revision: Because social phenomena are produced through interaction, they are never static but are always being revised and reshaped. Meanings and understandings are continuously negotiated and reconstructed as people interact.

Researcher’s role: In recent interpretations, constructionism also suggests that researchers' accounts of the social world are themselves constructions. Researchers cannot provide a definitive, objective account of reality; rather, they present one version of social reality shaped by their perspectives, experiences, and interpretations. This idea challenges the notion that knowledge is fixed or absolute.

Opposition to Objectivism and Realism: Constructionism is fundamentally opposed to objectivism, which views social phenomena as existing independently of human perception. It is also contrary to realism, which posits that there is an objective reality that can be known.

Constructionism is an ontological perspective that challenges the idea that social phenomena, such as organizations and cultures, exist as fixed, external realities independent of social actors. Instead, constructionism emphasizes that these phenomena are continuously created and revised through social interaction.

Organizations as Negotiated Orders: Constructionism views organizations not as rigid structures but as social realities shaped through ongoing negotiations and agreements among individuals. Formal rules and hierarchies exist but are often flexible, functioning more as general guidelines shaped by everyday interactions.

Culture as Continuously Constructed: Rather than being a static, external force that constrains behavior, culture is seen as an emergent reality, continuously formed and adapted by people to address new situations. Although culture has pre-existing elements, it remains in a state of constant reconstruction.

Social Categories as Social Constructs: Categories like "masculinity" are not seen as fixed entities but as meanings built through social interaction. These meanings can change over time and across contexts, often analyzed through discourse.

Intersectionality: Linked to constructionism, intersectionality theory highlights how social categories (e.g., race, gender) interact and shape social realities. It emphasizes the importance of considering multiple, intersecting identities to understand how the social world is constructed.

Intersectionality definition: Intersectionality is a theoretical framework that emphasizes the interconnectedness of different social categories, such as gender, race, class, and sexuality. It argues that these categories cannot be understood separately because they intersect to shape an individual’s experiences and opportunities in unique ways. The concept is rooted in the work of Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989), although it draws from earlier insights, especially those of Black feminists, who highlighted how various social identities create both shared and diverse experiences among women.

Intersectional Analysis: Intersectionality is used across the social sciences to analyze how overlapping social identities affect individuals’ experiences of privilege or disadvantage. The main goal is to transform power structures and address multiple forms of oppression.

Categorical complexities defined by Leslie McCall:

Intra-Categorical complexity: Focuses on the specific intersections of social categories, examining how they interact to shape unique experiences. It questions the creation and boundaries of categories but acknowledges that some social identities are stable over time. For instance, Wingfield’s study (2009) on minority men in nursing shows that race and gender intersect to limit upward mobility for Black men, unlike their White male counterparts.

Inter-Categorical complexity: A relational approach that examines how different social categories interact and shape experiences. It compares categories like race and gender to reveal patterns of privilege and disadvantage, often using quantitative methods. This approach highlights that categories like "gender" and "race" are intertwined, with each influencing the other.

Anti-Categorical complexity: A postmodern critique that deconstructs social categories, treating them as fluid and unstable constructs. This approach views categories as artificial and emphasizes the dynamic, contextual, and historically grounded nature of social identities. It argues that categories cannot be separated and must be analyzed in their full complexity.

Critiques: While intersectionality has been influential, it has been criticized for lacking a clear methodological framework and guidance on how to use it for social change. However, these critiques are often attributed to misunderstandings or poor application rather than flaws in the theory itself.

Ontology and Social Research: Ontological beliefs about the nature of social reality shape research approaches. If organizations and cultures are seen as objective entities, research focuses on structures and values. If viewed as socially constructed, the emphasis is on how people actively shape these realities. These assumptions influence research design and data.

Quantitative vs qualitative:

Quantitative research: Emphasizes numerical data and uses measurement for data collection and analysis. It typically follows a deductive approach, testing theories and adhering to the scientific model of positivism. Quantitative research views social reality as external and objective.

qualitative research: Focuses on words and meanings rather than numbers. It often follows an inductive approach, aiming to generate theories and understanding social phenomena through the lens of interpretivism. It views social reality as a dynamic creation of individuals.

The distinction between quantitative and qualitative research is commonly used, though debated. Quantitative research focuses on measurement, theory testing, and views reality as objective, while qualitative research emphasizes understanding social meanings and views reality as constructed. However, the divide isn’t strict; research often incorporates elements from both, and mixed methods research is increasingly common.

Further influences on how we conduct social research: impact of values and practical considerations:

1. values: values reflect the personal beliefs or the feelings of a researcher and there are different views about the extent to which they should influence research: a)value free approach, b)reflexive approach, c)conscious partiality approach.

a) Value free approach of Émile Durkheim: The value-free approach in social research is the principle that researchers should suppress their own values, biases, and preconceptions to maintain objectivity and scientific rigor. Social facts should be studied as "things" and that researchers must eliminate any biases or values that could influence their findings. In phenomenology, this idea is supported through the use of epoche or "bracketing," where researchers consciously set aside their own experiences and values to remain neutral. While the value-free approach aims to ensure the validity and scientific credibility of research, there is increasing acknowledgment that complete value neutrality is difficult, if not impossible, to achieve. Even within traditions that advocate for value-free research, there is a growing understanding that researchers' values inevitably influence their work.

b) The reflexive approach: The reflexive approach in social research acknowledges that research cannot be completely value-free. Reflexivity involves researchers actively examining and recognizing how their social location—factors such as gender, age, ethnicity, education, and background—affects the data they collect, analyze, and interpret. It is an ongoing process of self-awareness, where researchers consider how their values and biases influence various aspects of their work, including:

à formulation of research questions;

à choice of method;

à formulation of research design and data-collection techniques;

à implementation of data collection;

à analysis of data;

à interpretation of data;

à conclusions.

The reflexive approach also involves acknowledging how researchers' emotions or sympathies, especially when studying marginalized or "underdog" groups, can impact their objectivity. For example, Turnbull’s study of the Ik tribe highlighted how his Western values influenced his negative perception of the tribe's family practices. He emphasized the importance of transparency, admitting that his values shaped his observations.

c) The conscious partiality approach: The conscious partiality approach acknowledges and embraces the influence of values in research. Instead of striving for neutrality, this approach involves deliberate and intentional alignment with particular values or perspectives. Mies, a proponent of this approach, argues that in research—especially feminist research—value-free neutrality should be replaced with partial identification with research subjects.Researchers practicing conscious partiality use theoretical frameworks, such as feminist, Marxist, or postcolonial perspectives, to guide their research:

Feminist Approach: Highlights the disadvantages women and marginalized groups face due to patriarchal systems.

Marxist Approach: Emphasizes the impact of class divisions and capitalism on socioeconomic inequalities.

Postcolonial Approach: Critiques the ethnocentric and Western-centric biases in knowledge production.

This approach views the influence of values not as a limitation but as a purposeful and meaningful component of the rest

it also recognize the impact the researcher has on the studies they produce, the influence of the researcher’s values and social position, alongside other social categories, are unavoidable.

Practical considerations in social research: Practical issues are crucial in deciding how to carry out social research. Three key factors include:

Nature of research questions: The choice between quantitative and qualitative methods depends on the type of questions asked. For example, exploring causes of a social phenomenon may require a quantitative approach, while understanding the views of a social group may call for a qualitative approach.

Existing research: If there is little prior research on a topic, a qualitative, exploratory approach might be more suitable, as it can generate theories. In contrast, established topics with measurable concepts might be better suited for a quantitative strategy.

Topic and participants: For sensitive or marginalized groups, such as those involved in illegal or stigmatized activities, qualitative methods are often preferable to build trust and gather meaningful data. Survey methods may not be practical in these cases, and sometimes covert research is used, though it raises ethical concerns.

Cap 3: research designs

What is a research design?

Definition: A research design provides a structured framework for the systematic collection and analysis of data in a research study. It outlines how data will be gathered and analyzed to answer research questions or test hypotheses. The research design serves as a strategic blueprint guiding all aspects of a research project.

Characteristics of research design:

Causal connections: Defines how to analyze cause-and-effect relationships between variables.

Generalizability: Determines if findings can apply to larger populations beyond the study sample.

Contextual understanding: Helps interpret behavior within its social and cultural context.

Temporal perspective: Examines social phenomena over time to understand patterns and connections.

What is a research method?

A research method is simply a technique for collecting data. It can involve a specific instrument, such as a self-completion questionnaire or a structured interview schedule (a list of prepared questions); or participant observation, whereby the researcher listens to and watches others; or the analysis of documents or existing data.

What is a variable?

Variable: A variable is an attribute or characteristic on which cases differ. Examples include sex, age, ethnicity, or educational attainment. Cases can be individuals or larger entities like households, cities, or organizations. If an attribute does not vary among cases, it is considered a constant.

Independent variable: An independent variable is one that influences or causes changes in another variable. It is the factor presumed to affect or predict the dependent variable. For example, sex could be an independent variable affecting hourly wage.

Dependent variable: A dependent variable is the attribute that is influenced or changed by the independent variable. It is the outcome or effect in the study. Using the previous example, hourly wage is the dependent variable affected by sex.

Quality and criteria in social research:

Reliability, replication, validity.

1. Reliability: Reliability refers to the consistency of a study's results when repeated under the same conditions. It addresses whether the measures used for concepts, such as poverty or relationship quality, produce stable and consistent outcomes. In quantitative research, reliability is crucial, as it ensures that measures do not fluctuate unpredictably. For instance, if an IQ test yields widely varying scores for the same person across different administrations, the test would be deemed unreliable.

2. Replication: Replicability refers to the ability of a study to be reproduced or repeated using the same methods and procedures. For a study to be replicable, the original research must clearly document its design, participants, data collection, and analysis. Replication is often done to test if findings are consistent over time or across different groups. Although replication is valued in quantitative research, it is less common in academic research due to the emphasis on originality. Despite this, replicability ensures that research findings are reliable and can be confirmed through repeated studies.

3. Validity:Validity refers to the accuracy and integrity of the conclusions generated from research. It assesses whether the research truly measures or reflects what it claims to and whether the results can be trusted and applied beyond the study.

Different types of validity:

Measurement validity: This applies mainly to quantitative research and concerns whether the tool used truly measures the concept it claims to measure. For example, an IQ test should accurately measure intelligence. If a measure is inconsistent (unreliable), it cannot be valid.

Internal validity: This relates to the causal relationship between variables. It asks whether the conclusion that one variable (independent) causes changes in another variable (dependent) is convincing and credible. Internal validity ensures that we can confidently say that the observed effects are due to the independent variable.

External validity: This refers to the generalizability of the research findings beyond the specific context or participants of the study. High external validity means the results can be applied to broader populations, not just the study sample. It depends on how representative the sample is of the larger population.

Ecological validity: This focuses on whether research findings are applicable to real-life, everyday social settings. If research is conducted in unnatural environments, like laboratories, the findings may have limited ecological validity because they may not reflect real-world behavior.

Inferential validity: This concerns whether the conclusions and inferences drawn from the research are justified and supported by the data. It examines if the research design and interpretation are appropriate for making the claims. For instance, inferring causality from a study with a cross-sectional design is often considered invalid.

Differences in the relevance of criteria for quantitative and qualitative strategy:

Quality criteria such as reliability, measurement validity, internal validity, external validity, and ecological validityare generally more aligned with quantitative research methods, which emphasize structured measurements, causality, and the generalizability of findings. Here’s how these criteria relate to research strategies:

Reliability and Measurement Validity: These are most relevant to quantitative research, where the goal is to use reliable and valid measures for data collection. Quantitative strategies require consistency in tools and methods to ensure the accuracy and replicability of findings.

Internal Validity: This is crucial for establishing causal relationships between variables, which is typically a primary focus of quantitative research strategies. Quantitative research designs, like experiments, are built to maximize internal validity by controlling for confounding variables.

External Validity: Although relevant to both research strategies, external validity is especially important in quantitative research, where the emphasis is on ensuring findings can be generalized to broader populations. Quantitative studies often use large, representative samples to achieve this.

Ecological Validity: This criterion applies to both quantitative and qualitative research, as it addresses how naturally research settings reflect real-life environments. Qualitative research particularly values ecological validity, as it seeks to understand behavior in natural contexts, while quantitative research may also aim to maintain realistic conditions in certain studies.

Relationship:

The relationship between quality criteria and research strategy highlights that quantitative research focuses on structured, generalizable, and causally sound findings, which align well with concerns about reliability, measurement, and both internal and external validity.

Qualitative research, on the other hand, often prioritizes understanding context and experiences, making ecological validity more critical. Ultimately, each research strategy emphasizes different quality criteria based on its objectives and methodological approach.

Further qualitative research criteria: Qualitative research often uses different criteria to assess the quality of studies compared to quantitative research, though there are similarities. The main quality criteria for qualitative research include:

Credibility: This parallels internal validity in quantitative research. It addresses the believability and trustworthiness of the findings, asking whether the research accurately reflects the reality or experiences of the participants.

Transferability: This corresponds to external validity and considers whether the findings can be applied to other contexts or settings. While qualitative research does not usually aim for broad generalizability, it emphasizes detailed descriptions that allow others to determine if findings are applicable elsewhere.

Dependability: Similar to reliability, this criterion examines whether the research findings are consistent and repeatable over time. It involves ensuring that the research process is documented transparently so others can follow the study’s methods.

Confirmability: This is akin to objectivity in quantitative research. It evaluates whether the researcher has maintained a degree of neutrality and whether findings are shaped by the participants' responses rather than researcher bias. Researchers must show that their findings are based on data and not influenced by their personal values.

Similarities between quantitative and qualitative research:

Parallels in concepts: Both approaches strive for credibility in their findings—whether it be internal validity in quantitative research or credibility in qualitative research. Similarly, transferability and external validity both concern the generalizability or applicability of results to different settings.

Importance of rigor: Both research strategies require rigorous documentation and transparency. For qualitative research, dependability is akin to reliability, emphasizing the need for a systematic approach to ensure findings can be trusted.

Ecological validity: Both methods recognize ecological validity, though it is more naturally aligned with qualitative research. Qualitative research often seeks to collect data in real-world, natural settings, which enhances the ecological validity of its findings.

Week 2:

Different research designs:

1. Experimental designs: classical, laboratory and quasi experiment

2. Cross-sectional/survey

3. Longitudinal design

4. Case study design

5. Comparative design.

1) Experimental design: Experimental design refers to a structured research approach used to establish causal relationships between variables. It typically involves manipulating one or more independent variables to observe the effect on dependent variables. Experimental designs are categorized into classical experiments and quasi-experiments and can occur in field or laboratory setting.

Variants of experimental design:

Classical experiments:

These designs have a clear structure, often involving random assignment of participants to different conditions (e.g., experimental and control groups) to ensure internal validity. They aim to establish a strong causal link between variables.

Key features include randomization, control over variables, and pre-testing and post-testing.

Quasi-experiments:

These have some characteristics of classical experiments but lack full control, such as random assignment. Quasi-experiments are often used when randomization is not feasible or ethical.

They are still designed to infer causal relationships but with less certainty compared to classical experiments.

Settings of experimental eesign:

Field experiments:

Conducted in real-life environments, such as schools, workplaces, or as part of policy implementations. Field experiments are common in social research because they provide high ecological validity, reflecting real-world conditions.

Laboratory experiments:

Conducted in a controlled, artificial setting (e.g., a laboratory) to minimize external influences. These experiments allow for high control over variables but may lack ecological validity because the setting does not reflect natural environments.

1. Classical experiments: The classical experimental design, also known as a randomized controlled trial (RCT), is a rigorous research method used to establish causal relationships. It is highly regarded in research fields like social psychology, organizational studies, and political science, but is less common in sociology. This design is known for its strong internal validity, which allows researchers to confidently attribute observed effects to the manipulation of the independent variable. Classical experimental designs are characterized by manipulation, random assignment, control groups, and pre/post-testing, making them ideal for establishing causal relationships.

Features of classical experimental design:

Manipulation of the independent variable:

The independent variable is deliberately manipulated by the researcher to observe its effect on the dependent variable. This controlled intervention is what distinguishes classical experiments from non-experimental research.

Random assignment:

Participants are randomly allocated to either an experimental group (treatment group) or a control group. Random assignment ensures that the groups are comparable and that any observed differences in outcomes can be attributed to the experimental manipulation rather than preexisting differences.

Control group and experimental Group:

The experimental group receives the treatment or intervention, while the control group does not. This comparison allows researchers to isolate the effect of the independent variable.

For example, in the Rosenthal and Jacobson study, teachers had higher expectations (treatment) for the "spurters" (experimental group), while other students (control group) did not receive this special expectation.

Pre-Test and Post-Test measurement:

The dependent variable is measured before (T1) and after (T2) the experimental intervention. This "before-and-after" design helps establish whether the manipulation caused a significant change in the dependent variable.

High internal ialidity:

Because of the random assignment and controlled conditions, classical experiments have high internal validity. Researchers can be confident that any observed effects are due to the manipulation of the independent variable and not other factors.

Challenges of classical experimental design:

Difficulty in manipulation:

Many social variables, like gender or social class, cannot be manipulated. This makes it hard to use true experimental designs for certain research questions.

Controlled settings:

True experiments often require controlled environments, which can be difficult to achieve in real-world settings, limiting the feasibility of classical experiments in social research.

Internal validity in classical experiments:

Internal validity refers to the extent to which a study can establish a causal relationship between the independent and dependent variables, free from alternative explanations. In the context of classical experimental design, internal validity is crucial to ensure that the manipulated variable is indeed causing the observed effect. Classical experimental design uses control groups and random assignment to minimize threats to internal validity, ensuring that any observed effects are due to the experimental manipulation. However, even with strong internal validity, researchers must critically assess whether their measures are valid and whether the experimental manipulation effectively worked as intended.The use of control groups and random assignment helps minimize threats to internal validity. Key threats to internal validity include:

1. History

Definition: Events or changes in the environment occurring between the pre-test and post-test, other than the manipulation, could affect the results.

Example: In the Rosenthal and Jacobson study, an external event like a new school policy aimed at improving academic performance could influence student scores.

Solution: The presence of a control group helps control for these events, as both groups are exposed to the same external influences.

2. Testing

Definition: The act of taking a pre-test might influence participants' behavior or responses in the post-test, either by making them more experienced with the test or by sensitizing them to the study’s purpose.

Solution: The control group also takes the pre-test, ensuring that any testing effects are consistent across groups.

3. Instrumentation

Definition: Changes in the way a measurement or test is administered (e.g., slight alterations in the test format) could lead to differences in results.

Solution: Using a control group ensures that any changes in testing procedures affect both groups equally, isolating the effect of the experimental manipulation.

4. Mortality/Attrition

Definition: The loss of participants over time, which can threaten the validity of the study, especially if dropout rates are high or systematic.

Example: In a long-term study, some students may leave the area or transfer to other schools.

Solution: Since attrition affects both the experimental and control groups, it does not necessarily threaten the validity of the findings if it occurs evenly.

5. Maturation

Definition: Natural changes in participants over time (e.g., growing older or developing new skills) that may affect the dependent variable.

Example: Students might improve academically simply because they are getting older and more experienced, not because of the experimental manipulation.

Solution: Since maturation affects both groups equally, any observed difference can be attributed to the experimental treatment.

6. Selection

Definition: Differences between the experimental and control groups due to how participants were selected or assigned.

Solution: Random assignment of participants to groups minimizes this threat by ensuring that any pre-existing differences are distributed randomly.

7. Ambiguity About the Direction of Causal Influence

Definition: Uncertainty about whether the independent variable truly affects the dependent variable or whether the causal relationship could be reversed.

Solution: In classical experimental designs, the independent variable is manipulated before measuring the dependent variable, ensuring a clear temporal sequence and causal direction.

Ensuring internal validity

Control Group and Random Assignment: These are essential features of classical experimental design. They help eliminate confounding factors and rival explanations, providing a stronger basis for inferring causality.

Measurement validity concerns: Even if a study has high internal validity, researchers must also evaluate whether the measurements accurately reflect the concepts being studied. For example, in the Rosenthal and Jacobson study, questions about the validity of IQ test scores or measures of intellectual curiosity could impact the study’s overall conclusions.

External validity in classical experiments:

External validity is critical for determining whether the findings of an experiment can be extended to other people, places, and times. Threats such as interaction of selection, setting, history, pre-testing, and experimental arrangements highlight the complexities of applying results beyond the specific conditions of the study. Understanding these threats helps researchers design experiments that are more robust and applicable to real-world situation.

external validity refers to the extent to which the findings of an experiment can be generalized beyond the specific conditions and participants involved in the study. It considers whether the results are applicable to other populations, settings, or times. Campbell and Cook identified several threats to external validity that could limit this generalizability:

1. Interaction of selection and treatment

Definition: This threat questions whether the findings can be generalized to different social and psychological groups. It asks whether the results are applicable to a wide range of people differentiated by factors such as ethnicity, social class, gender, and personality type.

Example: In the Rosenthal and Jacobson study, the students were primarily from lower-social-class backgrounds and ethnic minority groups. This specific sample may limit the generalizability of the results to other groups with different characteristics.

2. Interaction of setting and treatment

Definition: This threat addresses whether the results are applicable in different settings. It questions if findings from one environment, such as a specific school, can be applied to other schools or broader contexts.

Example: The study's findings were influenced by the unique cooperation and conditions of a particular school, raising doubts about whether the same effects of teacher expectancies would occur in other educational or non-educational settings.

3. Interaction of History and Treatment

Definition: This threat considers whether findings from a study conducted at a specific time can be generalized to other time periods, both in the past and future.

Example: The Rosenthal and Jacobson research was conducted over 50 years ago. There is uncertainty about whether the self-fulfilling prophecy effect would be observed in today’s educational settings or whether the timing within the academic year influenced the results.

4. Interaction effects of Pre-Testing

Definition: This threat arises when the pre-testing of participants affects how they respond to the experimental treatment, making the results less generalizable to situations where pre-testing does not occur.

Example: In the Rosenthal and Jacobson study, students were pre-tested, which may have sensitized them to the experimental conditions. This raises concerns about whether the findings would apply to groups that have not been pre-tested, as pre-testing is not common in real-world scenarios.

5. Reactive effects of experimental arrangements (reactivity)

Definition: This threat refers to the awareness of participants that they are part of an experiment, which could influence their behavior and make the findings less generalizable to natural settings.

Example: In this case, Rosenthal and Jacobson’s subjects were likely unaware that they were participating in an experiment, which reduced the reactive effects. However, in many experiments, participants’ awareness could alter their behavior, affecting the generalizability of the results.

Ecological validity in classical experiments:

In classical experimental design, experiments conducted in field settings (e.g., schools, workplaces, or public spaces) are generally considered to have higher ecological validity than those conducted in laboratory settings. This is because field experiments take place in environments where participants behave more naturally. However, several factors can challenge ecological validity:

Data collection methods: The use of specific measurement tools, such as surveys or standardized tests, may introduce an artificial element to the study. Even if the setting is natural, the methods themselves could influence participants’ behavior in ways that do not reflect real-world interactions.

Awareness of being studied: If participants are aware that they are part of an experiment, this awareness can alter their behavior, reducing ecological validity. However, if the experiment is designed so that participants remain unaware, it helps maintain natural behavior but may raise ethical concerns, particularly when deception is involved.

Replicability in classical experiments:

For a classical experiment to be considered replicable, researchers must thoroughly document their methods, including the selection of participants, the manipulation of variables, and data collection processes. This allows other researchers to replicate the study under similar conditions. However, there are challenges: