Chapter 21: Late-Nineteenth-Century Art

Key Notes

- Time Period

- Realism: 1848–1860s

- Impressionism: 1872–1880s

- Post-Impressionism: 1880s–1890s

- Symbolism: 1890s

- Art Nouveau: 1890s–1914

- Culture, beliefs, and physical settings

- Europe and the Americas experience great innovation in economics, industrialization, war, and migration. There is a strong advancement in social issues.

- The avant-garde emerges as artists express themselves in various new movements.

- Marx and Darwin had philosophies that affected the world.

- Cultural interactions

- Architecture is expressed in a series of revival styles.

- Artists are exposed to diverse, sometimes exotic, cultures as a result of colonial expansion.

- Material Processes and Techniques

- Architecture is affected by new materials and new modes of construction.

- Artists use new media including photography, lithography, and mass production.

- Audience, functions, and patron

- Commercial galleries become important. Museums open and display art. Art sells to an ever-widening market.

- Artists work for private and public institutions to a sometimes-critical public.

- The importance of academies diminishes, and many artists work without patronage.

- Women artists become increasingly important.

- Theories and Interpretations

- Audiences and patrons were often hostile to art made in this period.

- Art history as a science continues to be shaped by theories, interpretations, and analyses applied to these new art forms.

Historical Background

- Europe in 1848 saw a wave of revolutions challenging the old order and seeking democracy.

- Louis-Philippe, the "Citizen King" of France, was deposed and replaced by Napoleon III, leading to belligerency and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870.

- Social reformers were influenced by positivism, a theory that accepted only proven ideas based on science.

- Nineteenth-century thinkers like Darwin and Marx added to positivism by exploring theories on human evolution and social equality.

- New inventions such as telephones, motion pictures, bicycles, and automobiles shrank the world by opening communication to a wider audience.

- Artists rejected traditional subject matter and chose to represent peasant scenes, landscapes, and still lifes, inspired by the spirit of modernism.

- Systematic and scientific archaeology began during this period with excavations in Greece, Turkey, and Egypt.

Patronage and Artistic Life

- Many artists were dissatisfied with the conservative nature of the Salon of Paris and sought recognition elsewhere.

- Rejected artists like Courbet and Manet set up oppositional showcases, achieving fame by being antiestablishment.

- The emergence of the art gallery provided a more comfortable viewing experience than the Salon, featuring carefully selected works of art in tastefully appointed surroundings.

- Cézanne cultivated the persona of the struggling and misunderstood artist and was one of the first to exploit the stereotype of the artist as rebel.

- Other artists like Gauguin and van Gogh followed suit, escaping to exotic locations for inspiration.

- European artists were greatly influenced by an influx of Japanese art, particularly their prints, which broke European conventional methods of representation.

- The plein-air movement characterized Impressionism, as artists moved their studios outdoors to capture the effects of atmosphere and light on a given subject.

- Lithography was a new creative outlet for printmakers in the late nineteenth century, with politically inclined artists like Daumier using the medium to critique society’s ills and others like Toulouse-Lautrec using it to mass-produce posters of the latest Parisian shows.

- Japonisme: an attraction for Japanese art and artifacts that were imported into Europe in the late nineteenth century

- Lithography: a printmaking technique that uses a flat stone surface as a base. The artist draws an image with a special crayon that attracts ink. Paper, which absorbs the ink, is applied to the surface and a print emerges

- Caricature: a drawing that uses distortion or exaggeration of someone’s physical features or apparel in order to make that person look foolish

- Modernism: a movement begun in the late nineteenth century in which artists embraced the current at the expense of the traditional in both subject matter and in media. Modernist artists often seek to question the very nature of art itself

- Plein-air: painting in the outdoors to directly capture the effects of light and atmosphere on a given object

- Positivism: a theory that expresses that all knowledge must come from proven ideas based on science or scientific theory; a philosophy promoted by French philosopher Auguste Comte (1798–1857)

- Skeleton: the supporting interior framework of a building

- Zoopraxiscope: a device that projects sequences of photographs to give the illusion of movement

Realism

- Realist painters believe in depicting things that can be experienced with the five senses.

- Inspired by the positivism movement, Realist painters focus on the lower classes and their environments.

- Peasants are often painted with reverence, emphasizing their basic honesty and sincerity.

- Realist paintings show peasants in harmony with the earth and the landscape.

- Dominant hues in Realist paintings are brown and ochre.

- Courbet's statement "Show me an angel, and I'll paint one" reflects the Realist philosophy.

➼ The Stone Breakers

Details

- By Gustave Courbet

- 1849

- Oil on canvas

- Formerly in Gemäldgalerie, Dresden, destroyed in 1945

Content

- Peasants are breaking stones down to rubble to be used for paving.

- Poverty emphasized.

- The figures are born poor, will remain poor their whole lives.

- No idealization of peasant life or of the working poor.

Form

- Large massive figures dominate the composition; a style usually reserved for mythic figures in painting.

- Thick heavy paint application.

- Browns and ochres are dominant hues reflecting the drudgery of peasant life.

- Concentration on the main figures; little in the foreground or background to detract from them.

Function

- Submitted to the Salon of 1850–1851.

- Large size of painting usually reserved for grand historical paintings; this work elevates the commonplace into the realm of legend and history.

Context

- Reaction to labor unrest of 1848, which demanded better working conditions.

- Reflects a greater understanding of those who spend their entire lives in misery; cf. Dickens’s novels.

Image

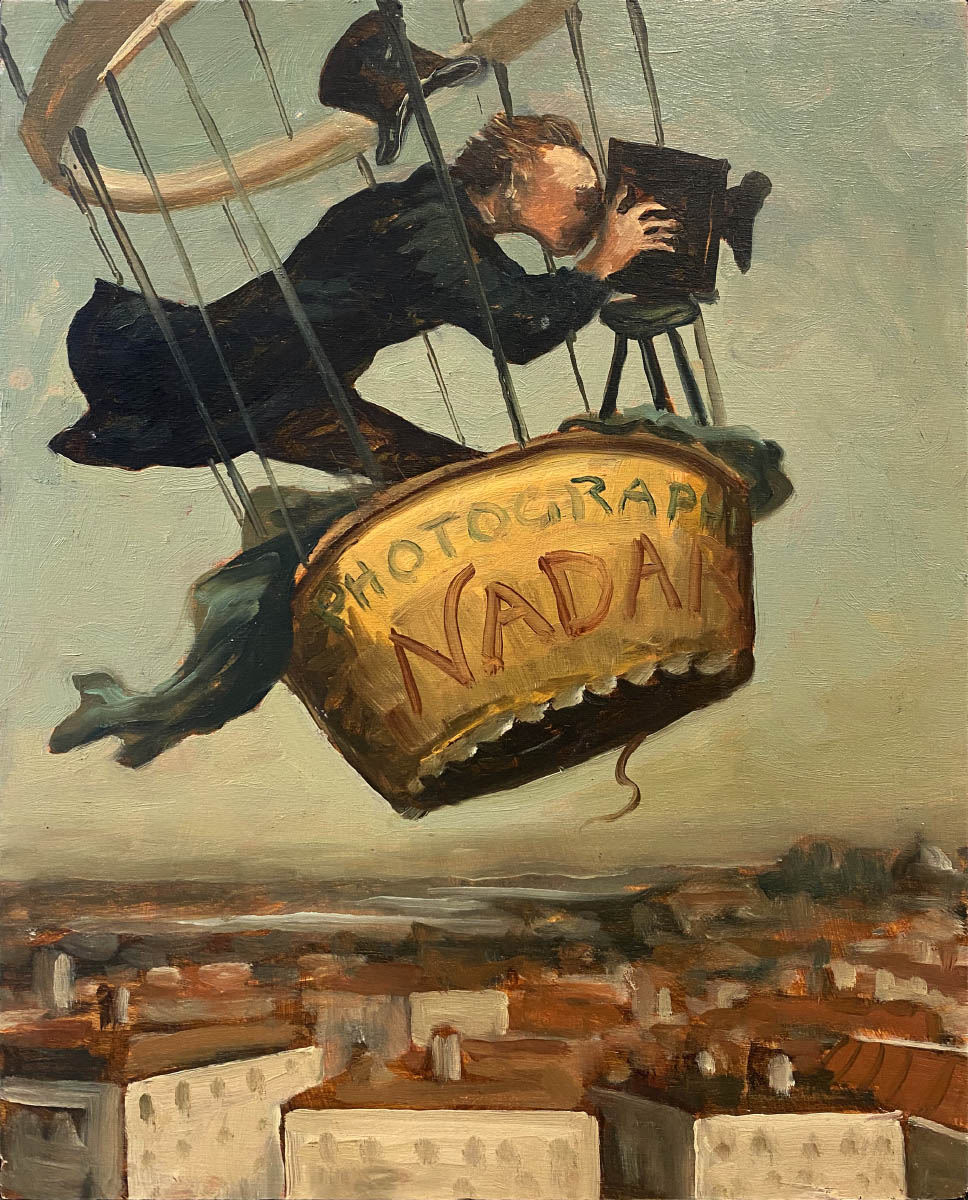

➼ Nadar Raising Photography to the Height of Art

Details

- By Honoré Daumier

- 1862

- A lithograph

- Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York

Content

- Nadar often took his balloon over Paris to photograph scenes from above.

- Daumier was a satiric artist who portrayed political and social events with a critical eye.

Function: Originally appeared in a journal, Le Boulevard, as a mass-produced lithograph.

Context

- The print satirizes the claims that photography can be a “high art;” irony implied in title.

- Nadar was famous for taking aerial photos of Paris beginning in 1858.

- The work was executed after a court decision in 1862 that determined that photographs could be considered works of art; this is Daumier’s commentary.

- Presents Nadar as a silly photographer; in his excitement to get a daring shot he almost falls out of his balloon and loses his hat.

- Photography used as a military tool: Nadar’s balloon reused in the 1870 siege of Paris.

- Every building has the word “Photographie” on it; foreshadows modern surveillance photographs, drones with cameras, Google Earth.

Image

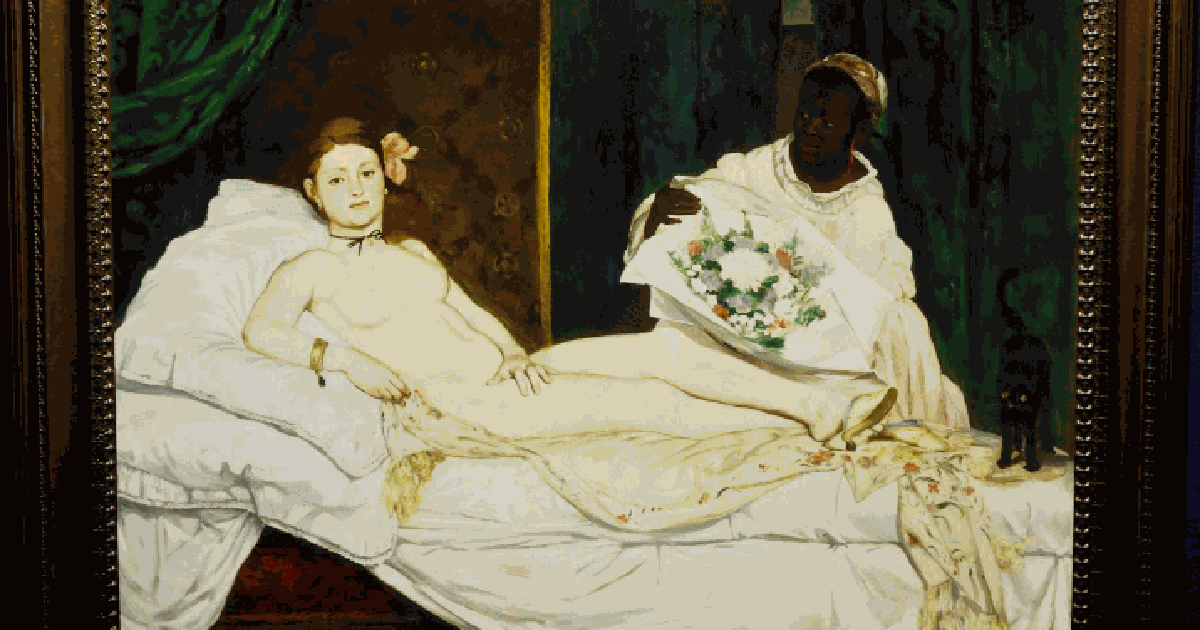

➼ Olympia

Details

- By Édouard Manet

- 1863

- Oil on canvas

- Found in Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Form and Content

- Olympia’s frank, direct, uncaring, and unnerving look startled viewers.

- The figure is cold and uninviting; no mystery, no joy.

- No idealization of the female nude.

- The maid delivers flowers from an admirer; a cat responds to our entry into the room.

- Simplified modeling; active brushwork.

- Stark contrast of colors.

Reception: Exhibited at the Salon of 1865; created a scandal.

Context

- Olympia was a common prostitute name of the time.

- A mistress was common to upper-class Parisian men, often sympathetically portrayed in contemporary literature, but never so brazenly depicted as in this painting.

- The painting is inspired by Titian’s Venus of Urbino and seen as a modern commentary on the classical feminine nude.

- This painting is a reaction to academic art that was based on Renaissance and classical ideals.

- Images of prostitutes and black women are not new with this painting, but Manet creates a dialogue between the nude prostitute and the clothed black servant, named Laure, which brings up issues of sexuality, racism, and stereotypes.

Image

➼ The Valley of Mexico from the Hillside of Santa Isabel

Details

- By Jose María Velasco

- El Valle de México desde el Cerro de Santa Isabel

- 1882

- Oil on canvas

- Found in National Art Museum, Mexico City

Form

- Dramatic perspective; small human figures.

- The painting depicts Tepeyac and offers a sweeping view of the Valley of Mexico, the basilica of the Lady of Guadalupe, as well as Mexico City and two volcanoes in the distance.

- The work glorifies the Mexican countryside as well as emerging industrialism with the depiction of the train.

- The artist as a keen observer of nature: rocks, foliage, clouds, waterfalls.

Context

- The artist was primarily an academic landscape painter.

- Velasco specialized in broad panoramas of the Valley of Mexico.

- He rejected the realist landscapes of Courbet; he preferred the romantic landscapes of Turner.

- The artist settled in Villa Guadalupe with an overview of the Valley of Mexico.

Image

➼ The Horse in Motion

Details

- By Eadweard Muybridge

- 1878

- Albumen Print

Patronage

- Hired by Leland Stanford (the founder of Stanford University) to settle a bet to see if a horse’s four hooves could be off the ground at the same time during a natural gallop.

Technique

- The photographer used a device called a zoopraxiscope to settle the bet.

- Cameras snap photos at evenly spaced points along a track, giving the effect of things happening in sequence.

- For the time, it was very fast shutter speeds, nearly 1/2000th of a second.

- Photography now advanced enough that it can capture moments the human eye cannot.

- These motion studies bridge the gap between still photography and motion pictures.

Content

- One photograph with sixteen separate images of a horse galloping.

- Images could be played in sequence to simulate motion pictures.

Image

Impressionism

- Impressionism is a modernist movement led by avant-garde artists.

- It emphasizes the transient, quick, and fleeting, seeking to capture the effects of light on a surface.

- Avant-garde: an innovative group of artists who generally reject traditional approaches in favor of a more experimental technique

- Impressionists believe that shadows contain color and that time of day and season affect appearance.

- Working in plein-air, they use a wide color range from subtle harmonies to stark contrasts of brilliant hues.

- Impressionists primarily focus on landscape and still-life painting, often with an urban viewpoint.

- Some specialize in human figures in movement, while others abandon figure painting altogether.

- Japanese art had a significant influence on Impressionism.

- Impressionism was originally anti-academic and anti-bourgeois, but it is now seen as the hallmark of bourgeois taste.

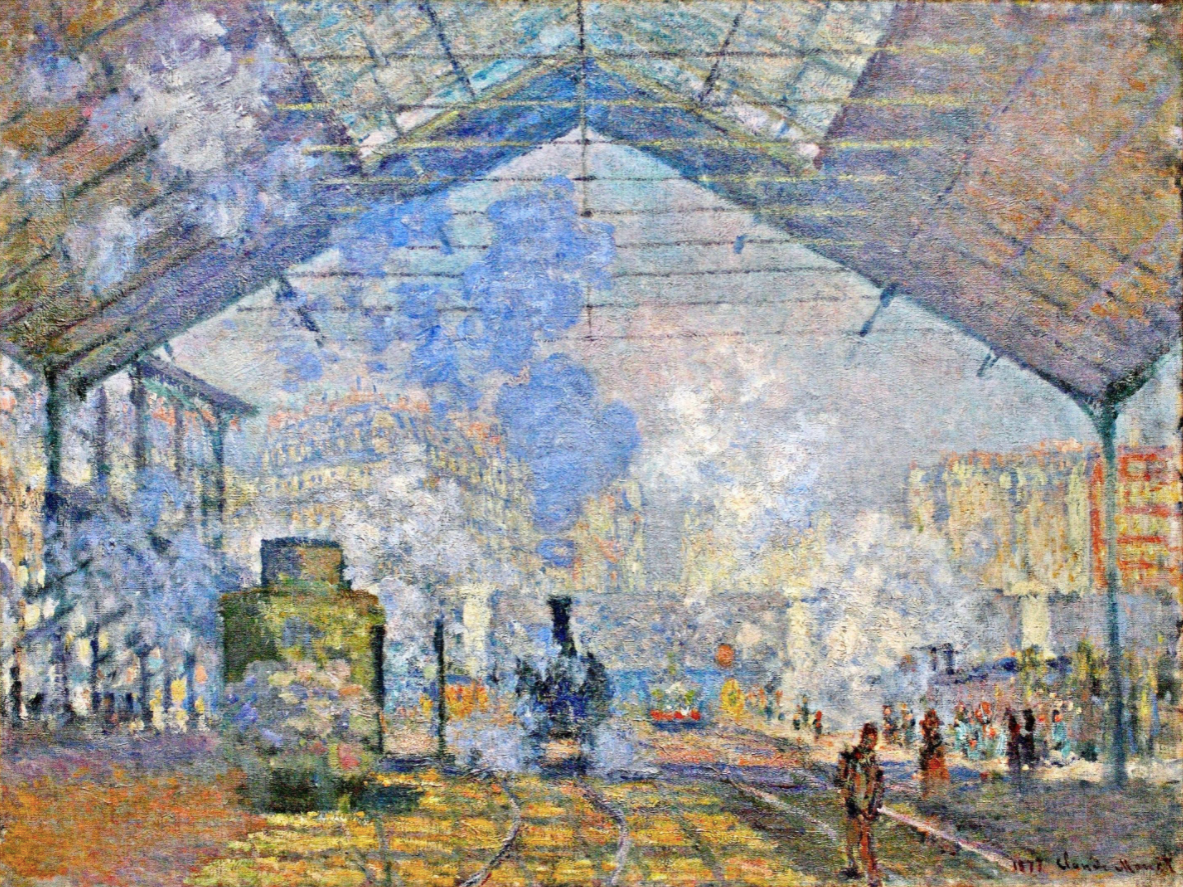

➼ The Saint-Lazare Station

- Details

- By Claude Monet

- 1877

- Oil on canvas

- Found in Musée d’Orsay, Paris

- Form

- Effects of steam, light, and color; not really about the machines or travelers.

- Subtle gradations of light on the surface.

- Forms dissolve and dematerialize; color overwhelms the forms.

- Figures are painted in a sketchy way with brief brushstrokes.

- Content

- The painting depicts the interior of a train station in Paris; a modern marvel of engineering.

- Trains were propelled by steam; accent on the energy of the steam rather than the train that produces it.

- History: Exhibited at the Impressionist exhibition of 1877.

- Context

- One of a series depicting this train station.

- Monet is famous for painting a series of paintings on the same subject at different times of day and days of the year.

- Originally meant to be hung together for effect: Haystacks were his first group to hang this way.

- Shows modern life in Paris with great industrial iron output.

- New view of a modern city that reflects Haussmann’s redesign of Paris.

- Image \n

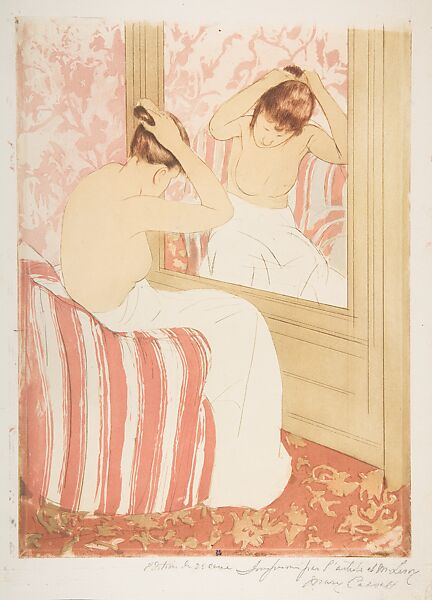

➼ The Coiffure

- Details

- By Mary Cassatt

- 1890–1891

- Drypoint and aquatint

- Found in Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Form

- Aquatint: a kind of print that achieves a watercolor effect by using acids that dissolve onto a copper plate

- Drypoint: an engraving technique in which a steel needle is used to incise lines in a metal plate. The rough burr at the sides of the incised lines yields a velvety black tone in the print

- No posing or acting; the figures possess a natural charm.

- Cassatt’s work possesses a tenderness foreign to other Impressionists.

- The figures are from everyday life.

- Pastel color scheme.

- The work contains contrasting sensuous curves of the female figure with straight lines of the furniture and wall.

- Japanese influence:

- Decorative charm.

- Japanese hair style.

- Japanese point of view: figure seen from the back.

- Graceful lines of the neck.

- Function: Part of a series of ten prints exhibited together at a Paris gallery in 1891.

- Technique

- Drypoint and aquatint.

- Drypoint yields soft dense lines.

- Aquatint is generally used with engravings like drypoint; it also yields flat colored areas on a print.

- Context: Cassatt’s world is filled with women; women as independent and not needing men to complete

- Image \n

Post-Impressionism

- Post-Impressionist painters, who followed the Impressionists, incorporated an analysis of structure along with their emphasis on light, shading, and color.

- Paul Cézanne, a prominent Post-Impressionist, aimed to make Impressionism more stable and enduring like traditional museum art.

- Post-Impressionist artists often incorporated elements of abstraction while retaining solid forms and exploring underlying structure.

- They also preserved traditional elements such as perspective, despite their experimentation with abstraction.

➼ Starry Night

- Details

- By Vincent van Gogh

- 1889

- Oil on canvas

- Found in Museum of Modern Art, New York

- Form

- Thick, short brushstrokes.

- Heavy application of paint called impasto.

- Parts of the canvas can be seen through the brushwork; artist need not fill in every part of the surface.

- Strong left-to-right wave-like impulse in the work broken only by the tree and the church steeple.

- The tree looks like green flames reaching into a sky that is exploding with stars over a placid village.

- Context

- The mountains in the distance are the ones that Van Gogh could see from his hospital room in Saint-Rémy; steepness exaggerated.

- Combination of images: Dutch church, crescent moon, Mediterranean cypress tree.

- Cypresses were often associated with cemeteries.

- Landscape painting was popular in the late nineteenth century as a reaction to the industrialization of cities.

- Image \n

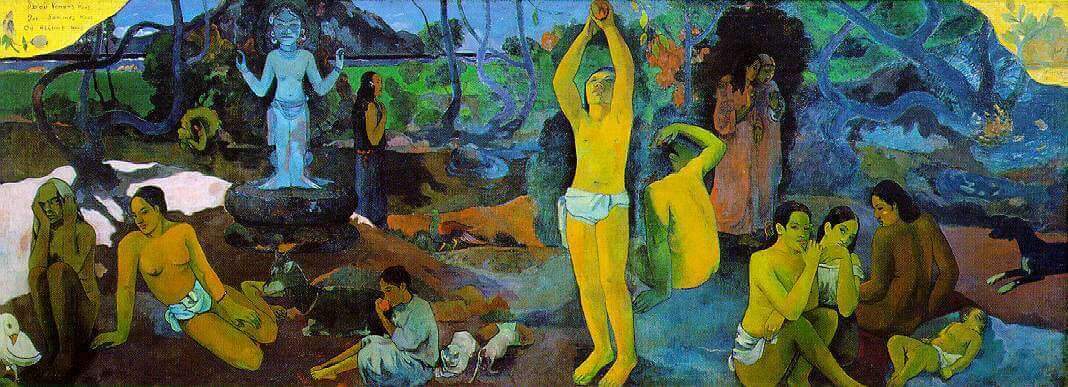

➼ Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?

- Details

- By Paul Gauguin

- 1897–1898

- Oil on canvas

- Found in Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Content

- The story of life, read right to left.

- Right: birth, infant, and three adults—the beginning of life.

- Center: mid life; picking of the fruit of the world.

- Left: death (a figure derived from a Peruvian mummy exhibited in Paris, cf. The Scream); the old woman seems resigned.

- The blue idol with arms half-raised represents “The Beyond.”

- The figures in foreground represent Tahiti and an Eden-like paradise; background figures are anguished, darkened figures.

- Context

- Title of the painting poses more questions than it answers.

- Gauguin thought the painting was a summation of his artistic and personal expression.

- Painted during his second stay in Tahiti between 1895–1901.

- Gauguin suffered from poor health and poverty, obsessed by thoughts of death.

- He learned of the death of his daughter, Aline, in April 1897 and was deeply shaken; he was determined to commit suicide and have this painting be his artistic last will and testament.

- Influences

- Many nontraditional influences:

- Egyptian figures used for inspiration.

- Japanese prints in the solid fields of color and unusual angles.

- Tahitian imagery in the Polynesian idol.

- A rejection of Greco-Roman influence.

- Image \n

➼ Mont Saint-Victoire

- Details

- By Paul Gauguin

- 1902–1904

- Oil on canvas

- Found in Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia

- Form

- Used perspective through juxtaposing forward warm colors with receding cool colors.

- Cézanne had contempt for flat painting; wanted rounded and firm objects, but ones that were geometric constructions made from splashes of undiluted color.

- Not a momentary glimpse of atmosphere, as in the Impressionists, but a solid and firmly constructed mountain and foreground.

- The landscape is seen from an elevation.

- Cézanne’s landscapes rarely contain humans.

- Three horizontal sections divide the painting, connected by a complex series of diagonals that bring your eye back.

- The viewer is invited to look at space, but not enter.

- Cézanne allows blank parts of the canvas to shine through.

- Broad brushstrokes dominate the painted surface.

- Context

- One of 11 canvases of this view painted near his studio in Aix in the south of France; the series dominates Cézanne’s mature period.

- Not the countryside of Impressionism; more interested in geometric forms rather than dappled effects of light.

- Image \n

Symbolism

- Symbolist artists reacted against the realistic art movement, believing that unseen forces and inner experiences were more important.

- Symbolists embraced a mystical philosophy that viewed dreams and inner experiences as the source of artistic inspiration.

- Symbolist painters varied greatly in their styles, ranging from the primitive, flat quality of Rousseau's work to the expressionistic swirls of Munch's art.

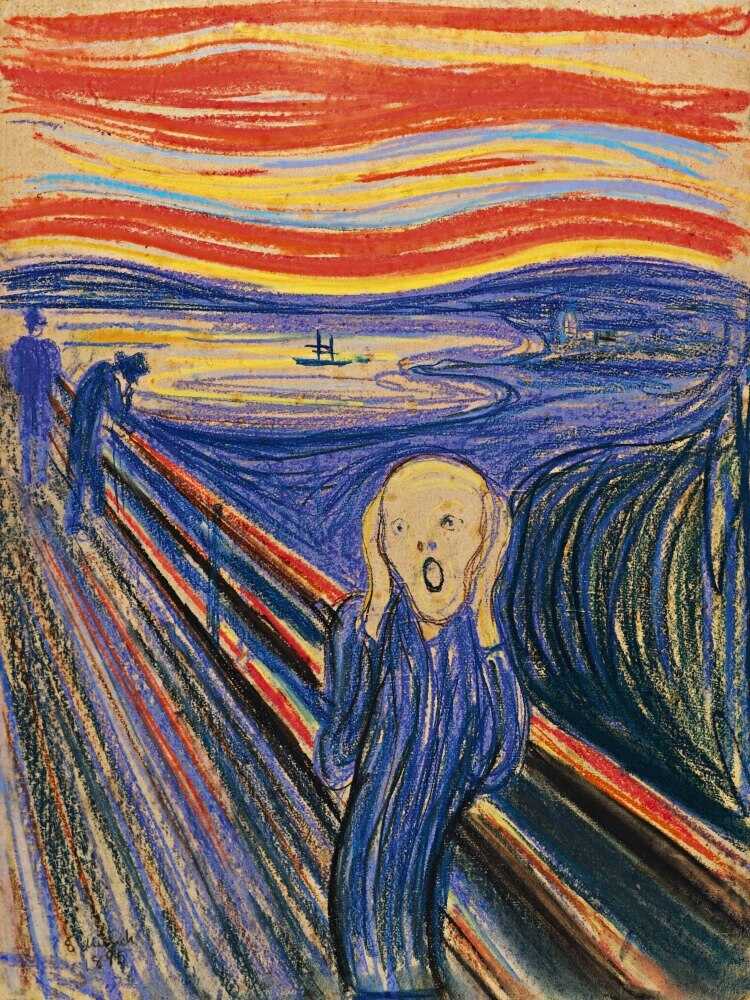

➼ The Scream

- Details

- By Edvard Munch

- 1893

- Tempera and pastels on cardboard

- Found in National Gallery, Oslo

- Form and Content

- The figure walks along a wharf; boats are at sea in the distance.

- Long, thick brushstrokes swirl around the composition.

- The figure cries out in a horrifying scream; the landscape echoes his emotions.

- Discordant colors symbolize anguish.

- Emaciated, twisting stick figure with skull-like head.

- Function: Painted as part of a series called The Frieze of Life; a semi autobiographical succession of paintings.

- Context

- Said to have been inspired by an exhibit of a Peruvian mummy in Paris.

- The work prefigures Expressionist art.

- The work is influenced by Art Nouveau swirling patterns.

- Image \n

Art Nouveau

- Art Nouveau was a European art movement that emerged in the late 19th century and lasted until the outbreak of World War I in 1914.

- The movement originated in a few artistic centers in Europe, including Brussels, Barcelona, Paris, and Vienna.

- Art Nouveau aimed to unify various artistic media into one integrated experience, with buildings being designed, furnished, and decorated by the same artist or artistic team.

- The style of Art Nouveau is characterized by vegetal and floral patterns, complexity of design, and undulating surfaces.

- The movement favored curvilinear lines over straight ones.

- Wrought ironwork was often used for decorative elements such as balconies, fences, and railings in Art Nouveau design.

➼ The Kiss

- Details

- By Gustav Klimt

- 1907–1908

- Oil and gold leaf on canvas

- Found in Austrian Gallery, Vienna

- Form

- Little of the human form is actually seen: two heads four hands, two feet.

- The bodies are suggested under a sea of richly designed patterning.

- The work is spaced in an indeterminate location against a flattened background.

- Context

- The male figure is composed of large rectangular boxes; the female figure is composed of circular forms.

- The work suggests all-consuming love; passion; eroticism.

- The use of gold leaf is reminiscent of Byzantine mosaics

- The work is influenced by gold applied to medieval illuminated manuscripts.

- Part of a movement called the Vienna Succession, which broke away from academic training in schools at that time.

- Image \n

Late Nineteenth Century Architecture

The movement toward skeletal architecture increased in the late nineteenth century.

Architects and engineers worked in the direction of a curtain wall, which is a building held up by an interior framework and an exterior wall made of glass or steel.

The emphasis was on the vertical due to increasing land values in modern cities.

Tall pilasters were used to emphasize verticality and windows were set back behind them.

The Chicago School made the greatest advances in architecture after the Great Fire of 1871.

- Buildings were covered in traditional terra cotta or ironwork and wrapped in terra cotta casings to withstand high temperatures.

- Chicago buildings demanded open and wide window spaces for light and air.

- The Chicago window was developed with a central immobile windowpane flanked by two smaller double-hung windows that opened for ventilation.

➼ Louis Sullivan, Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Building

Details

- 1899–1903

- Iron, steel, glass, and terra cotta

- Found in Chicago

Form

- Horizontal emphasis on the exterior mirrors the continuous flow of floor space on the interior.

- The exterior is covered in decorative terra cotta tiles; original interior ornamentation elaborately arranged around lobby areas, hallways, elevator; interior ornamentation now lost.

- The architect designed maximum window areas to admit light, but also to make displays visible from the street.

- Nonsupportive role of exterior walls; held up by an interior framework.

- Open ground plan allows for free movement of customers and goods.

Function: A department store on a fashionable street in Chicago.

Context

- Some historical touches exist in the round entrance arches and the heavy cornice at the top of the building.

- Cast iron decorative elements transformed the store into a beautiful place to buy beautiful things.

- Shows the influence of Art Nouveau in decorative ironwork on the entrance.

- Sullivan motto: “Form follows function.”

Image

Late Nineteenth Century Sculpture

- Late-nineteenth-century sculpture, symbolized by Rodin, was characterized by the visible imprint of the artist's hand on a given work.

- Sculptures were usually molded by hand in clay and then cast in bronze or cut in marble by a workshop.

- The sculptor would then put finishing touches on the work, which they conceived but did not necessarily execute entirely.

- The physical imprint of the hand was comparable to the visible brushstroke in Impressionist painting.

➼ The Burghers of Calais

Details

- By Auguste Rodin

- 1884–1895

- Made of bronze

- Found in Calais, France

Function and Reception

- Commissioned by the town of Calais in 1885 to commemorate six burghers who offered their lives to the English king in return for saving their besieged city during the Hundred Years’ War in 1347.

- Town council of Calais said it was inglorious; they wanted a single allegorical figure.

- In 1895, more than 10 years after Rodin presented the first maquette, it was installed at the entrance of the Jardin du Front Sud, on a pedestal designed by the city architect Decroix, with an octagonal iron gate around it.

- Rodin resented this installation and wanted the work mounted on a very low, “but impressive,” base on the Place d’Armes in the center of Calais.

- Meant to be placed on the ground so that people could see it close up. Context

- Rodin’s direct literary source is Jean Froissart (ca. 1333–1410) who described how King Edward of England demanded the six citizens to appear before him bareheaded, only dressed with a sackcloth, with a rope around their necks and the keys to the town in their hands. He wanted them to sacrifice their lives for their town.

- The English king was impressed by the self-sacrifice and allowed the citizens to live.

- Parallels between Paris besieged during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and Calais besieged by the English in 1347.

Context

- Rodin's inspiration for his sculpture "The Burghers of Calais" comes from Jean Froissart's account of King Edward of England demanding six citizens to appear before him bareheaded, dressed only in sackcloth with a rope around their necks and the keys to the town in their hands.

- The king wanted them to sacrifice their lives for their town.

- The English king was impressed by the self-sacrifice and allowed the citizens to live.

- Parallels between Paris besieged during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and Calais besieged by the English in 1347.

Form

- Figures sculpted individually and then arranged as the artist thought best.

- Rodin concentrates on the figures’ misery, doubt, and internal conflict.

- Each has a different emotion: some fearful, or resigned, or forlorn.

- Figures suffer from privation; they are weak and emaciated.

- The men are placed on an equal level, symbolizing their uniform sacrifice.

- The central figure is Eustache de Saint-Pierre, who has large, swollen hands and a noose around his neck, ready for his execution.

- Details are reduced to emphasize an overall impression.

Image