Chapter 10: Early Medieval Art

Key Notes

- Time Period

- Merovingian Art: 481–714 (from France)

- Hiberno-Saxon Art: 6th–8th centuries (British Isles)

- Culture, beliefs, and physical settings

- Early Medieval art is a part of the medieval artistic tradition.

- In the Early Medieval period, royal courts emphasized the study of theology, music, and writing.

- Early Medieval art avoids naturalism and emphasizes stylistic variety.

- Text is often incorporated into Early Medieval artworks.

- Cultural interactions

- There is an active exchange of artistic ideas throughout the Middle Ages.

- There is a great influence of Roman art on Early Medieval art.

- Audience, functions and patron

- Works of art were often displayed in religious or court settings.

- Surviving architecture is mostly religious.

- Theories and Interpretations

- The study of art history is shaped by changing analyses based on scholarship, theories, context, and written records.

- Contextual information comes from written records that are religious or civic.

Historical Background

- In the year 600, almost everything that was known was old.

- The great technological breakthroughs of the Romans were either lost to history or beyond the capabilities of the migratory people of the seventh century.

- This was the age of mass migrations sweeping across Europe, an age epitomized by the fifth-century king, Attila the Hun, whose hordes were famous for despoiling all before them.

- The Vikings from Scandinavia, in their speedy boats, flew across the North Sea and invaded the British Isles and colonized parts of France.

- Other groups, like the notorious Vandals, did much to destroy the remains of Roman civilization.

- So desperate was this era that historians named it the “Dark Ages,” a term that more reflects our knowledge of the times than the times themselves.

- However, stability in Europe was reached at the end of the eighth century when a group of Frankish kings, most notably Charlemagne, built an impressive empire whose capital was centered in Aachen, Germany.

Patronage and Artistic Life

- Monasteries were the principal centers of learning in an age when even the emperor, Charlemagne, could read, but not write more than his name.

- Artists who could both write and draw were particularly honored for the creation of manuscripts.

- The concept that artists should be creative and communicate something new in each work was unknown in the Middle Ages.

- Scribes copied the Bible and medical treatises, not modern literature or folk stories.

- Scribes had to retain the original phrasing, while artists had to balance conventional and new methods.

- Thus, a manuscript's text is usually an exact duplicate of a constantly recopied book, but the pictures offer the artist considerable latitude.

Early Medieval Art

- One of the great glories of medieval art is the decoration of manuscript books, called codices, which were improvements over ancient scrolls both for ease of use and durability.

- A codex was made of resilient antelope or calf hide, called vellum, or sheep or goat hide, called parchment.

- These hides were more durable than the friable papyrus used in making ancient scrolls.

- Hides were cut into sheets and soaked in lime in order to free them from oil and hair.

- The skin was then dried and perhaps chalk was added to whiten the surface.

- Artisans then prepared the skins by scraping them down to an even thickness with a sharp knife; each page had to be rubbed smooth to remove impurities.

- The hides were then folded to form small booklets of eight pages.

- The backbone of the hide was arranged so that the spine of the animal ran across the page horizontally.

- This minimized movement when the hide dried and tried to return to the shape of the animal, perhaps causing the paint to flake.

- Illuminations were painted mostly by monks or nuns who wrote in rooms called scriptoria, or writing places, that had no heat or light, to prevent fires.

- Vows of silence were maintained to limit mistakes.

- A team often worked on one book; scribes copied the text and illustrators drew capital letters as painters illustrated scenes from the Bible.

- Scriptorium: a place in a monastery where monks wrote manuscripts

- Manuscript books had a sacred quality.

- The word of God; had to be treated with appropriate deference.

- Covered with bindings of wood or leather, and gold leaf was lavished on the surfaces.

- Precious gems were inset on the cover.

- Objects are done in the cloisonné technique, with horror vacui designs featuring animal style decoration.

- Interlace patternings are common.

- Images enjoy an elaborate symmetry, with animals alternating with geometric designs.

Merovingian Art

- Merovingians: A dynasty of Frankish kings who, according to tradition, descended from Merovech, chief of the Salian Franks.

- Power was solidified under Clovis (reigned 481–511) who ruled what is today France and southwestern Germany.

- The Frankish custom of dividing property among sons when a father died led to instability because Clovis’s four male descendants fought over their patrimony.

- Royal burials supply almost all our knowledge of Merovingian art.

- A wide range of metal objects were interred with the dead, including personal jewelry items like brooches, discs, pins, earrings, and bracelets.

- Garment clasps, called fibulae, were particular specialties.

- They were often inlaid with hard stones, like garnets, and were made using chasing and cloisonné techniques.

- Chasing: to ornament metal by indenting into a surface with a hammer

- Cloissonné: enamelwork in which colored areas are separated by thin bands of metal, usually gold or bronze

➼ Merovingian looped fibulae

Details

- Early medieval Europe

- Mid-6th century

- Made of silver gilt worked in filigree with semiprecious stones, inlays of garnets and other stones

- Found in Musee d’Archeologie Nationale, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

Form

- Zoomorphic elements—fish and bird, possibly Christian or pagan symbols.

- Highly abstracted forms derived from the classical tradition.

- Zoomorphic: having elements of animal shapes

Function

- Fibula: a pin or brooch used to fasten garments; showed the prestige of the wearer.

- Small portable objects.

Context

- Found in a grave.

- Probably made for a woman.

Image

Hiberno Saxon Art

- Hiberno Saxon art: The art of the British Isles in the Early Medieval period.

- Hibernia: the ancient name for Ireland.

- Hiberno Saxon art relies on complicated interlace patterns in a frenzy of horror vacui.

- Horror vacui: (Latin, meaning “fear of empty spaces”) a type of artwork in which the entire surface is filled with objects, people, designs, and ornaments in a crowded, sometimes congested way

- The borders of these pages harbor animals in stylized combat patterns, sometimes called the animal style.

- Animal style: a medieval art form in which animals are depicted in a stylized and often complicated pattern, usually seen fighting with one another

- Each section of the illustrated text opens with huge initials that are rich fields for ornamentation.

- The Irish artists who worked on these books had exceptional handling of color and form, featuring a brilliant transference of polychrome techniques to manuscripts.

➼ Lindisfarne Gospels

- Details

- Early medieval Europe

- c. 700

- Made of illuminated manuscript, ink, pigments, and gold on vellum

- Found in British Library, London

- Gospels: the first four books of the New Testament that chronicle the life of Jesus Christ

- Function

- The first four books of the New Testament

- Used for services and private devotion.

- Materials: Manuscript made from 130 calfskins.

- Content

- Evangelist portraits come first, followed by a carpet page.

- These pages are followed by the opening of the gospel with a large series of capital letters.

- Context

- Written by Eadrith, bishop of Lindisfarne.

- Unusual in that it is the work of an individual artist and not a team of scribes.

- Written in Latin with annotations in English between the lines; some Greek letters

- Latin script is called half-uncial.

- English added around 970; it is the oldest surviving manuscript of the Bible in English.

- English script called Anglo-Saxon minuscule.

- Uses Saint Jerome’s translation of the Bible, called the Vulgate.

- Colophon at end of the book discusses the making of the manuscript.

- Colophon: a commentary on the end panel of a Chinese scroll; an inscription at the end of a manuscript containing relevant information on its publication

- Made and used at the Lindisfarne Priory on Holy Island, a major religious center that housed the remains of Saint Cuthbert.

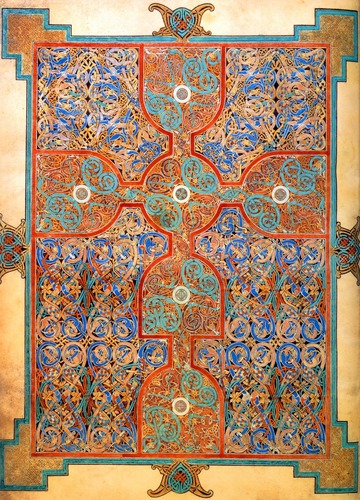

➼ Cross-carpet page

Details

- From the Book of Matthew from The Book of Lindisfarne

- c. 700

- Made of illuminated manuscript, ink, pigments, and gold on vellum

- Found in British Library, London

Form

- Cross depicted on a page with horror vacui decoration.

- Dog-headed snakes intermix with birds with long beaks.

- Cloisonné style reflected in the bodies of the birds.

- Elongated figures lost in a maze of S shapes.

- Symmetrical arrangement.

- Black background makes patterning stand out.

Context: Mixture of traditional Celtic imagery and Christian theology.

Image

➼ Saint Luke portrait page

Details

- From The Book of Lindisfarne

- c. 700

- Made of illuminated manuscript, ink, pigments, and gold on vellum

- Found in British Library, London

Context

- The traditional symbol associated with Saint Luke is the calf (a sacrificial animal).

- Identity of the calf is acknowledged in the Latin phrase “imago vituli.”

- Saint Luke is identified by Greek words using Latin characters: “Hagios Lucas.” There is also Greek text.

- Saint Luke is heavily bearded, which gives weight to his authority as an author, but he appears as a younger man.

- Saint Luke sits with legs crossed holding a scroll and a writing instrument.

- Influenced by classical author portraits.

Image

➼ Saint Luke incipit page

Details

- From The Book of Lindisfarne

- c. 700

- Made of illuminated manuscript, ink, pigments, and gold on vellum

- Found in British Library, London

Content

- This page is called “Incipit,” meaning it depicts the opening words of Saint Luke’s gospel: “Quoniam Quidem…”

- Numerous Celtic spiral ornaments are painted in the large Q; step patterns appear in the enlarged O.

- Naturalistic detail of a cat in the lower right corner; it has eaten eight birds.

- Incomplete manuscript page; some lettering not filled in.

Image