MICB 211 Unit 2 Case Studies

Chapter 8 Case Study 1

Objective: Study the role of cAMP in repressing lactose metabolism in the presence of glucose in E. coli

Background:

β-galactosidase is an enzyme encoded in lac operon (lacZ)

presence of β-galactosidase levels indicate activation/expression of lac operon

glycerol is a poor, alternative carbon source for E. coli

assume all levels of the sugars are considered high levels and that they grew bacteria for 100 minutes

Hypothesis: cAMP is involved in promoting lactose metabolism when there is little to no glucose because it helps activate the CAP protein

Control: glycerol used as negative control — no glucose, no lactose control. Glycerol treatment used to demonstrate that glucose/lactose has an effect (negative control).

Data

Fig. 1: β-galactosidase levels as an indication of activation/expression of the lac operon and total cAMP levels under 4 conditions. Glycerol is a poor carbon source for E. coli. cAMP levels don’t match low glucose levels → low glucose should have high cAMP levels but it is not displayed in this figure. Figure shows that cAMP grows in the absence of both glucose and lactose.

Fig. 2: Growth measured in OD600 and β-galactosidase activity under a condition where cAMP is added to the media at high levels and a strain that in unable to produce cAMP. Both cAMP grown in 0.4% glucose and 0.2% lactose (assume high levels).

Expected results doesn’t match curve of β-galactosidase when cAMP added — amount of β-galactosidase resulted matches expected results but the curve doesn’t match: There is a lag when cAMP added → not expected → there should be no lag (β-galactosidase should be highly expressed from the start)

Expected results doesn’t match curve of β-galactosidase and OD curve: no cAMP produced (CAP can’t bind to CAP site without cAMP) → low levels of β-galactosidase expressed not high levels of β-galactosidase shown in the curve

Conclusion: Refute hypothesis; cAMP is always present and the CAP is always bound to the CAP site, regardless of glucose levels, but cAMP always binds to CAP.

Chapter 8 Case Study 2

Characteristics of bacteriophage isolates and expression of Shiga toxin genes transferred to non Shiga toxin producing E.coli by transduction

Background: Shiga toxin is a type of bacterial toxin produced by pathogenic E. coli and S.dysenteriae

Objectives: Not all strains of E.coli can produce this toxin, but there is a concern that environmental bacteriophages are helping to transfer this toxin gene to non-toxin producing E.coli → bacteriophage transferring toxin

Hypothesis: Strains of phage carrying Shiga toxin that were most effective at infecting E.coli would also result in the highest rate of gene transfer

Data:

Table 1: Infection detection of 9 different Stx-encoding phage (each row) against 5 different non-toxic strains of E. coli (each column). + infection detected, - infection not detected. E.coli ATCC 9637 and E. coli ATCC 10536 strains infected by the highest number of phages (6) → strains that are most susceptible to phage infection.

Table 2: Detection of two types of Shiga toxin genes chromosomally in originally non-toxic E. coli strains (decreasing susceptibility). Stx1 gene has a higher rate of transfer → detected in a greater proportion of bacteria infected with different phages.

There is no correlation between E.coli strain susceptibility and presence of toxin gene → E.coli ATCC 9637 most susceptible but doesn’t have stx2 expression &&& E.coli ATCC 25922 least susceptible (only infected by 1 phage), but expressed both stx1 and stx2 → presence of toxin gene and susceptibility to infection aren’t correlated. E.coli ATCC 9637 should have both stx1 & stx2 IF there was a correlation since they are most susceptible but since they only have stx1 → no correlation between strain and susceptibility.

Table 3: Shiga toxin levels (stx1 and stx2) and bacterial cell viability with increasing salt concentration. Cell viability decreases with higher salt concentration (negative correlation). Maximum stx1 concentration at 6% NaCl concentration. Increasing NaCl induces stx1 production.

Conclusion: Bacteriophages can mediate the transfer of Shiga toxin through transduction (Shiga toxin (stx1) transferred more than stx2). More bacterial cell death observed under high osmotic pressure (higher salt concentration). Shiga toxin more highly expressed under high osmotic pressure (increased expression in high salt could correlate to gut conditions).

Chapter 9 Case Study 3

Aim: Study how S.enterica senses different metal ions using two two-component regulatory systems, PhoPQ & PmrAB

Background:

PhoPQ

-senses/responds to low Mg2+

-induces expression of pmrD

PmrAB

-senses/responds to high Fe2+

-induces expression of pbgP

-pmrA, pmrB, phoP or phoQ knock-out mutants

all 4 genes of the 2 two-component systems

-low Mg, high Fe: signals detected by sensors

what low and high levels are doesn’t matter

-lacZ activity = pbG expression/PmrA activity

easily measured

-PhoQ and PmrB are the sensors of 2 two-component systems

-PhoP and PmrA are the response regulators of the 2 two-component systems

Steps:

determine what signals can activate PmrA → cause pbgP expression

signals that can activate PmrA: low Mg (via PhoPQ response PmrD), high Fe (via PmrB)

crosstalk between PhoPQ and PmrAB

PmrA

create a reporter plasmid using promoters from genes that they suspect are regulated by PmrA

test reporter gene expression for each reporter in PhoQ mutant

need to eliminate chances of genes getting activated because of PhoPq (low Mg) instead of PmrAB (high Fe)

isolate impact of PmrA gene regulation

promoter: pbgP promoter

reporter gene: beta-galactosidase (lacZ)

create mutants for phoPq and pmrAB

Determine if two-component systems are involved in antibiotic resistance and test these strains to see if they are resistant to antibiotic polymyxin B

create strains where response regulators have been deleted

ΔPmrA or ΔPhoP

Data:

Fig. 1: A reporter plasmid created using promoter of pbgP in front of lacZ (b-galactosidase). B-galactosidase activity as an indicator of pbgP expression was measured in low Mg or low Mg and high Fe in knock-out mutants of pmrA, pmrB, phoP and phoQ. The no plasmid control are WT S.enterica cells not transformed with the reporter plasmid. Either low Mg or high Fe are minimally sufficient to activate PmrA.

Bacterial cells that are wild-type

low Mg alone is inducing expression (B-galactosidase)

Bacterial cells that are ΔpmrA

no expression with any levels of Mg or Fe

Bacterial cells that are ΔpmrB

no expression with any levels of Mg or Fe

Bacterial cells that are ΔpmrP

high Fe, low Mg results in expression

Bacterial cells that are ΔpmrQ

high Fe, low Mg results in expression

Fig. 2: ugd, pbgP, pmrC genes are regulated by PmrA

Fig. 3: both PhoPq and PmrAB play a role in resistance against polymyxin B. PmrAB confers more resistance against polymyxin B. Deleting pmrAB has more of an impact than phoPQ.

Conclusion:

PmrAB can be activated by either low MG (via PhoPQ) or high Fe (independent). PmrA regulates pbgP, ugd, pmrC found to be involved in antibiotic resistance.

Chapter 10 Case Study 4

Background: Outer membrane vesicles (OMV) are small lipid-enclosed packages that bud off from bacterial membranes. They contain DNA, RNA, proteins, antimicrobial compounds and they are able to bind and fuse with surface of other cells to deliver contents into another cell. These vesicles are a communication strategy and defense strategy to compete with other bacteria.

Objective: To determine if outer membrane vesicles made by B.thailandenis can interfere and inhibit planktonic growth and biofilm formation of Streptococcus mutans.

Hypothesis: B.thailandenis OMVs will possess antibiofilm activity against S.mutans

Step 1: Tested the B.thailandenis OMV’s effect on S. mutans planktonic growth (ie. non-biofilm cells) - Figure 1A & 1B

Step 2: Antimicrobial effects of OMVs and gentamicin in both planktonic and biofilm conditions were compared. This was measured by counting colony forming units (CFUs) - Figure 2B & 2C

Data

Fig. 1 (A): S.mutans grown on plate with PBS and 10 ug/mL of OMVs produced by B.thailandenis OMVs. Less growth where OMVs are compared to PBS condition. Planktonic lifestyle being studied in the agar plate (cells grown on culture media — free living and moving in nutrient rich conditions).

Fig. 1 (B): 4 different conditions; different concentrations of OMVs added with PBS as control being viewed through OD. OMVs do affect growth.

Fig. 2 (B &C): Bacteria growing in biofilms and planktonic culture were reduced to ~0 CFU/mL after treatment with OMVs.Planktonic and biofilm lifestyles are Burkholderia OMVs effective antimicrobials. Figure 2 more useful in treating a patient with S.mutans infection.

Fig. 3 (A, B, C): S. mutans biofilms grown for 3 days before treatment with (A) PBS, (B) 50 ug/mL or (C) 100 ug/mL OMVs for 24 hours. Following staining with live/dead BacLight fluorescent dye.

Fig. 3 (D): Most cells alive. S. mutans biofilms grown for 3 days before treatment with PBS, 50 ug/mL or 100 ug/mL OMVs for 24 hours. 50 ug/mL and 100 ug/mL significantly decrease biofilm thickness and biomass. These concentration of OMVs would be used to treat S.mutans.

Fig. 3 (E): Average thickness

Conclusions: Accept hypothesis; B.tailandenis OMVs are effective antimicrobials against both planktonic and biofilm S.mutans. The OMVs reduce biofilm cell density, potentially by increasing cell death and reducing biofilm thickness.

Chapter 10 Case Study 5

Background: Aggregation occurs when bacterial cells at high density cluster together and often part of initial phase of biofilm formation. Bacteria that are deficient in autoaggregation are also unable to form good biofilms. OD600 = 6.0 → bacteria grown in culture for a very long time.

cheY = binds flagella, causes tumble (CW)

flu = adhesion surface protein, allows bacteria to attach

tar = chemoreceptor

tsr = chemoreceptor

fliC = flagella component

motA = flagellar motor synthesis

lsrB = can’t sense or import AI2

lsrC = can’t import but can sense AI2

luxS = can’t make AI2

Aim: Explore whether both chemotaxis and quorum sensing are involved in regulating autoaggregation in E.coli.

is chemotaxis involved in autoaggregation

is quorum sensing involved in autoaggregation

Hypothesis: E.coli responds to AI2 (quorum sensing) by moving (chemotaxis) which promotes aggregation

instead of an environmental signal (ie. nutrient) to control chemotaxis, E.coli use quorum sensing signals to find each other, suggesting aggregation

Steps:

delete knockout genes involved in swimming & genes involved in chemotaxis

swimming - fliC, motA

chemotaxis - cheY, tar, tsr

delete because swimming is controlled by chemotaxis

Data

Fig. 1 (A-E): Autoaggregation is when bacteria are clumped together. The gene appearing to be important in regulating autoaggregation is flu, fliC, motA, cheY (all influence cluster formation).

Fig. 1 (F): Most area taken up is wild type. Least area taken up is removal of fliC and motA. CheY, tar, tsr, fliC, motA all are important in regulating autoaggregation.

Fig. 2 (A): Data collected from experiment using reporter plasmid with GFP under control of promoter from lsr operon. Activity of lsr promoter and AI-2 levels in the cell during growth of wild-type E.coli cultures. Fluorescence is measuring expression of Lsr operon. Exponential phase of growth is when quorum sensing is activated. High AI2 triggers quorum sensing. AI2 concentration increases with increasing population, leading to more expression of lsr operon.

Fig. 2 (B): Aggregation of wild type at different stages of growth. Measuring how much space is being taken up by clumps of bacteria. Higher bacterial load (more bacteria in culture) = more aggregation = more area. Low OD = low area.

Fig. 2 (C): Aggregation of strains defective in production (luxS), sensing and import (lsrB) or only import (lsrC) of AI-2. LuxS gene is most important in regulating autoaggregation. Without LuxS → no autoaggregation (LuxS makes AI2 → AI2 must be important).

Fig. 2 (D): Effects of indicated concentrations of supplemented AI-2 on aggregation of wild-type. Added AI-2 to medium and measured aggregation over time. Disconnected relationship between abundance and location of bacteria from AI2. The data matches what is expected considering the data in other Fig. 1 panels. Researchers’ hypothesis was that instead of an environmental signal, to control chemotaxis, E.coli uses quorum sense signals to find each other to promote aggregation. By adding AI2, they disconnect the relationship between bacteria & AI2 and interrupt AI2 gradient. AI2 levels are just high everywhere now, not just around bacteria so they can’t find each other to aggregate.

Fig. 3 (B): Biofilm formation in the wild-type and several knock-out mutants include flu (known to be important for autoaggregation). Δflu strain used as negative control condition for autoaggregation (since it’s known to impact biofilm formation). LsrB and CheY are equally important/significant other than flu for regulating biofilm formation.

CheY - bad at clustering

lsrB - very thin biofilm

Fig. 3 (C): Fluorescence micrographs of biofilms grown on a slide of the wild-type and 3 knock-outs.

Conclusion: Autoaggregation occurs when there is higher cell density which is also when quorum sensing activates. Quorum sensing seems important in mediating autoaggregation. Chemotaxis also play a role in regulating autoaggregation. Both chemotaxis and quorum sensing appear to be important for biofilm formation contributing to different characteristics of a good biofilm.

Chapter 11 Case Study 6

Background: Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an inflammatory bowel disease that causes inflammation and ulcers (sores) in the intestine.

Aim: Investigate changes in gut microbiome of children with UC (especially when steroids aren’t working)

Hypothesis: Patients with less diverse microbiome = worse disease.

1. Healthy microbiome will differ compared to patients with UC, especially patients for whom steroids aren’t working.

2. UC patients will exhibit a decrease in microbiome diversity that will correlate with increasing disease severity.

Data:

Fig. 1: Shannon index of biodiversity (accounts for richness & abundance/evenness). Higher diversity score = higher diversity. Healthy people have a more diverse gut microbial community than those with UC. Supports hypothesis 1; healthy microbiome is different from patients with UC.

Fig. 2: Measured relative abundance (ONLY ABUNDANCE) of bacteria from 9 phyla in healthy controls and UC patients. Compared healthy vs control microbiomes → looked for significant changes in abundance for each phylum. Significant differences between healthy control and UC for Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, Spirochaetes, Verrucomicrobia, Lentisphaerae. UC slightly increases evenness.

If combine data from Figure 1 and Figure 2, richness influences diversity more; bigger difference between healthy and UC patients in Fig. 1 than Fig. 2 so likely richness had a bigger impact.

Fig. 3: Number of species detected in fecal samples collected from healthy patients and patients with UC treated with steroid (Responders - UC patients that had improved symptoms, Non-responders - UC patients that didn’t have improved symptoms). Responders saw improvement in gut health and non-responders did not. Higher microbial richness is correlated with better gut health. Steroid treatment worked; made the microbiome of UC patients richer → predict that UC improved so they are likely feeling better.

Conclusion:

UC is associated with lower microbial diversity in the gut. Improving diversity is associated with improved gut health. Support hypothesis; Fig. 1 & 3 (hypothesis 1), Fig. 2 (hypothesis 2).

Chapter 12 Case Study 7

Background: N.gonorrhoeae is a bacterial pathogen with an adherence mechanism mediated by pili. Pili genes undergo changes during infection (mutations — look different to immune system, phase changes — expressed at different levels, in different places throughout infection). Mutations and phase changes help N.gonorrhoeae avoid immune system, increases adherence and promotes infection.

MS11 - original N.gonorrhoeae strain

G29, 4R1, SA, 7uB, 6uF, V4 - strains that were re-isolated from people infected with MS11 (undergone changes in pili due to mutation and phase changes; strains differ in ability to adhere and invade).

Hypothesis: Variants in pili genes will either increase or decrease N.gonorrhoeae adherence abilities and in turn increase or decrease severity of infection.

1. pili genes change during infection

2. these changes will alter adherence abilities

3. altered adherence will change the severity of infections

Methods:

Adherence

1. Grow human cells

2. Expose to strains of N.gonorrhoeae for 1.5 hrs, 3 hrs, 6 hrs

3. Collect samples and put on agar plates

4. Count number of N.gonorrhoeae colonies after 24 hours

Invasion

1. Grow human cells

2. Expose to strains of N.gonorrhoeae for 1.5 hrs, 3 hrs, 6 hrs

3. Add antibiotic to kill any N.gonorrhoeae outside of human cells

4. Collect samples and put on agar plates

5. Count number of N.gonorrhoeae colonies after 24 hours

Data:

Fig. 1 (A): Adherence of re-isolates and original strain (MS11) by measuring the amount of cells that have adhered or internalized in CFU. Adherence is based on sticking to cells; more bacteria stick = more bacteria grow on agar later.

Strain Y has more colonies on the agar plate → Strain Y adhered better to human cells.

7uB and 6uF showed improved adherence compared to MS11; they have higher levels of adherence compared to MS11.

4R1, Sa, V3 showed reduced adherence compared to MS11.

Fig. 2 (B): Internalization of re-isolates and original strain (MS11) by measuring the amount of cells that have adhered or internalized in CFU. Strain Y has more colonies on the agar plate → Strain Y invaded human cells to a greater extent.

4R1, V3 showed improved internalization compared to MS11; both have significantly greater levels of internalization.

Sa, 7uB, 6uF showed reduced internalization compared to MS11; both have significantly lower levels of internalization.

There is no correlation between better adherence and better internalization. Better adherence doesn’t translate to better internalization

strains with improved adherence appear to have reduced internalization (7uB & 6uF)

strains with reduced adherence (4R1 & V3) appear to have increased internalization

Sa has reduced adherence and reduced internalization

Improved | Reduced | |

Adherence | 7uB, 6uF | 4R1 (up to 3 hours), Sa, V3 |

Internalization | 4R1, V3 | Sa, 7uB, 6uF |

Conclusion: Hypothesis not supported; some strains showed improved or reduced ability to adhere and internalize but there was no clear correlation between improved adherence to internalization.

Chapter 12 Case Study 8

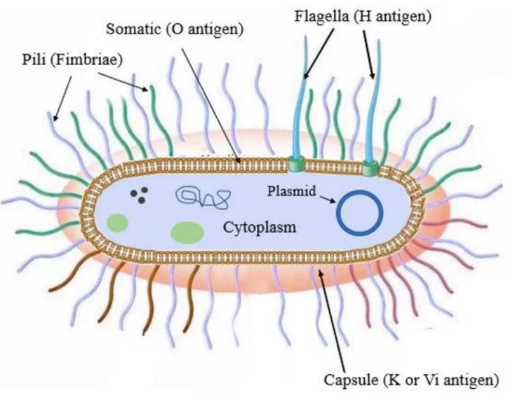

Background: S.pneumoniae is a capsule-encased bacteria that causes meningitis and pneumonia. S.pneumoniae strains have many variations or mutations in the capsule that are distinct. Different capsule versions = serotypes (over 90 different serotypes).

Serotype

O (LPS) : K (capsule) : H (flagella)

can classify or serotype bacteria based on surface components

K antigen - capsule sugars

O antigen - gram(-) LPS

H antigen - flagella

capsule, LPS and flagella each have several versions

keep track of these numbers/versions based on combination of LPS:Capsule:Flagella they express → serotypes

ex: E.coli O157:H7

O (LPS) version 157

H (Flagella) version 7

similar to how blood types are categorized in humans

ie. presence/absence of surface markers

Aim: Determine if capsule serotype directly affects S.pneumoniae disease severity.

Hypothesis: Changing capsule serotype will affect disease severity in an infant meningitis rat model.

Data:

Fig. 1: Clinical parameters assessed during acute bacterial meningitis in animals infected by inoculation with pneumococci. (A) survival (B) clinical scores of rats infected with serotype 6B or 7F strains. Lower scores = more severe infection/disease. 6B capsule serotype is more virulent because fewer rats survive infection after 16 hours (A). Rats have lower clinical score at 21 hours → more rats are unable to walk/sand or are in a coma (B).

(A): Rats were infected with either

106.66 (6B) — infectious clinical isolate [solid line]

1066.66cps208.41 (7F) [dotted line]

genetically altered isolate

has capsule genes replaced with a non-infectious capsule

only difference between 6B and 7F is which capsule is being expressed

counts number of surviving rats over time

(B): Rats were infected with either

106.66 (6B) — infectious clinical isolate [clear box]

1066.66cps208.41 (7F) [box with lines]

genetically altered isolate

has capsule genes replaced with a non-infectious capsule

only difference between 6B and 7F is which capsule is being expressed

measures rats’ clinical scores at 21 hours after infection

ability to stand

ability to walk

coma

lower score = worse performance

Fig. 2: Capsule thickness determined by serotype 6B (a, c) and serotype 7F (b, d) before inoculation of rats (a, b) and recovered from rats 21 hours after infection (c, d).

6B = infectious clinical isolate

7F = genetically altered isolate (capsule genes replaced)

Serotype 6B thicker after infection and serotype 7F thinner after infection *compared to before infection. 6B is more dense after infection; 7B less dense. The capsule thickness changed because host factors affect the capsule. Figure 2 correlates with data from figure 1 because 7F looks less virulent (= less able to cause disease) and less able to survive in the host.

Conclusions: Accept hypothesis; some capsule serotypes exhibit more virulence than others (S.pneumoniae serotype 6B more virulent than 7F). Capsule thickness during infection correlated with virulence (6B had thick capsule and was more virulent in rats and 7F capsule became thinner during infection and was less virulent in rats).

Chapter 12 Case Study 9

Background: V.cholerae is a pathogen that causes acute diarrheal disease (cholera). V.cholera serogroups O1 and O139 can produce cholera toxin (ctx) and cause disease. Different O serogroups means different versions of LPS. Non-O1 and non-O139 V.cholera strains often don’t have the cholera toxin gene (ctx) so they don’t cause outbreaks. Researchers identified 3 non-O1 and non-O139 strains that had ctx gene and cause infection.

Infection = growth and replication in a host

Disease = host damage/detrimental impacts (in this case → accumulation of fluid)

Strains that are non-O1 and non-O139 are non-toxic.

Cholera toxin causes accumulation of water in the intestine → intestinal cells can’t absorb water which leads to diarrhea. If a strain makes and secretes cholera toxin → fluid accumulation in the gut.

Hypothesis: Presence of ctx gene in non-O1, non-O139 strains make these non-toxic strains pathogenic.

Experimental Procedure/Data

Fig. 1(A/B): Rabbit intestine injected with

PBS = phosphate-buffered saline

negative control

N16961 = toxic V.cholerae (O1 or O1139, has a ctx gene)

positive control

No. 1, No. 2, No. 3 = non-O1, non-O139 → has ctx gene

A = non-O1, non-O13 → doesn’t have ctx gene

No. 1 and No. 2 strains of non-toxic V. cholera caused accumulation of fluid in intestine (based on fig. B). No.3 and A strains of non-toxic V.cholera are actually non-toxic/non-pathogenic (no disease). No.1 strain of non-toxic V.cholerae is most virulent (caused most retention of fluid → most virulent strain has most severe effects associated with pathogen).

Fig. 2: (Exotoxin measurement) Four strains of V.cholerae were grown at 25°C and 37°C

N16961 = toxic V.cholerae (O1/O139 has ctx gene)

positive control

No. 1, No. 2, No. 3 = non-O1, non-O139 → has ctx gene

Researchers measured amount of secreted cholera toxin (ctx) for each strain. No. 1 non-toxic strain can express and secrete cholera toxin (can’t say if this is biologically relevant to human infection — only tested in rabbit intestine). Fig. 1 does not correlate with Fig. 2 (No. 1 & No. 2 look pathogenic — caused retention in Fig. 1, but only No. 1 secreted toxin in Fig. 2).

Strain No. 1 not likely to cause disease in humans based on the information because it produces most cholera toxin at 25°C. Human body temperature is 37°C and levels of cholera toxin production were very low at that temperature.

Conclusion: No.1 non-toxic strain is theoretically pathogenic (encodes for virulence factor — cholera toxin). No. 1 demonstrated showed disease in both figures; No. 2 only showed disease in fig. 1 not fig. 2

Chapter 13 Case Study 10

Background: M.tuberculosis bacterium causes tuberculosis. Researchers are looking to see if the antimicrobial activity of 8-hydroxyquinoline (8HQ) could be enhanced by copper (Cu). Growing: actively replicating bacterial cells mTB cells by starving them → test efficacy of antibiotic 8HQ against dormant cells.

Recovery: dormant, non-replicating bacteria

Scientists can generate ‘recovery’ non-replicating mTB cells by s

Hypothesis: 8HQ antimicrobial activity is enhanced in the presence of Cu both in vitro and in vivo.

Experimental Procedure

Fig. 1

generate recovery mTB cells and growth mTB cells

make 8HQ concentration gradient with or without Cu added

test in liquid culture (A) and mIC plate (B)

transfer growing mTB and recovery mTB cells into nutrient-rich medium + 8HQ (± Cu)

assess ability of mTB to recover/survive

Fig. 2

Infect macrophages with mTB

incube for 4 hours

add antibiotic at varying concentrations

wait 48 hours

collect cells, lyse cells and culture remaining bacteria on agar plates

count number of mTB left after infection

Data

Fig. 1 (A): Fluorescence measure of bacterial cell count at different concentrations of 8HQ as growing (G) and recovering (R) cells in the presence or absence of copper (Cu). Recovering phenotype (independent of Cu) is more susceptible to 8HQ (smaller concentration of Cu used to kill bacteria). Cu affects 8HQ’s antimicrobial effect by making it more antimicrobial (less amount of 8HQ used to kill bacteria compared to regular Recovering and Growing) — cell death at lower concentrations of 8HQ.

Fig. 1 (B): MIC growing and recovery M.tuberculosis cells with (+) and without (-) copper. Recovery (independent of Cu) is more susceptible to 8HQ (lower MIC concentration). Cu affects 8HQ’s antimicrobial effect by making it more antimicrobial (lower concentration of 8HQ used to kill bacteria).

Based on both figures, the most effective treatment combination would be 2.5 um 8HQ + Cu (based on the chart and graph → no more growth of bacteria after 2.5 um — MIC).

Fig. 2: M.tuberculosis infected macrophages treated with 8HQ. Input = number of macrophages/mTB that was started with after 4 hours of infection before antibiotic (8HQ) treatment. 8HQ has antimicrobial activity against M.tuberculosis because the number of mTB bacteria goes down after treatment with 8HQ (significant differences between 0, 1, 10).

Cu | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) | |

G | - | > 10 (need to test with higher concentration) |

G | + | 2.5 |

R | - | 10 |

R | + | 2.5 |

Conclusions: Accept hypothesis; 8HQ antimicrobial is enhanced in the presence of Copper for in vivo and in vitro cells. Recovering cells are more susceptible to 8HQ. Copper promotes the antimicrobial effects of 8HQ. 8HQ works to help reduce M.tuberculosis infections of macrophages.

Chapter 13 Case Study 11

Background: Closely related to M.tuberculosis is M.abscessus. M.abscessus causes large lumps to grow on the skin and causes disease in lungs of immunocompromised people. Researchers want to know if a gene with no function, MAB_2385 is involved in antibiotic resistance in M.abscessus.

Etest: combination of disk diffusion and MIC

Hypothesis: Presence of gene MAB_2385 in M.abscessus will lead to streptomycin resistance.

Data

Fig. 1: Streptomycin Etest of

M.abscessus ATCC 19977T (wild-type)

MAB_2385 (gene)

ΔMAB_2385 (knock-out mutant)

pMV361-aac(3)IV-MAB_2385 (complementation vector)

ΔMAB_2385 pMC361-aac (3)IV-MAB_2385 (deletion with gene added back in on a plasmid)

MAB_2385 is involved in antibiotic resistance against streptomycin because the zone of inhibition goes back to normal after it is re-added into the bacteria (deleting gene makes M.abscessus more susceptible but when the gene is added back, M.abscessus is less susceptible again).

Strain | MIC |

Wild-type | 32/48/64 |

ΔMAB_2385 | 1.0/1.5/2 |

Complement | 96/128/192 |

Table 1: MIC of streptomycin against M.smegmatis strains with and without the MAB_2385 gene transformed into it. MAB_2385 makes M.smegmatis more resistant towards streptomycin (MIC increases when MAB_2385 added into M.smegmatis).

Fig. 1 and Table 1 data align with each other.

Conclusions: Deleting MAB_2385 makes M.abscessus less resistant to streptomycin. Adding MAB_2385 into M.smegmatis makes it resistant to streptomycin, therefore, MAB_2385 is a potential antibiotic resistance gene that can confer resistance against streptomycin.

Tutorial Case Study 1

Aim: Determine how gene expression of the arabinose operon is regulated by arabinose and glucose through AraR

Hypothesis: The ara operon is only activated when arabinose is present and glucose is absent; and AraR is a repressor.

Background: The ara operon is a series of genes that encode for proteins involved in metabolizing the sugar, arabinose. It has 4 promoter binding sites that regulate 6 genes (3 of the genes are contained as part of an operon, one gene is regulator AraR). Assume ara operon works like the lac operon (arabinose instead of lactose). AraR is repressor, CAP is activator.

Based on the arabinose operon, the promoter is controlling an “operon” is promoter B. The promoter(s) controlling single genes are promoter A, D, and C.

Conclusion:

Accept hypothesis; ara operon only gets activated when arabinose is present. Promoters for araA and araE are controlled in the same way in response to glucose and/or arabinose. Results are expected for glucose and arabinose treatment in figure 1 considering catabolite repression and assumption that this operon works like the lac operon.

No glucose, no arabinose

araR bound

CAP bound

low levels of transcription

Glucose & arabinose

araR not bound

CAP not bound

basal levels of transcription

Glucose, no arabinose

araR bound

CAP not bound

low levels of transcription

No glucose, Arabinose

araR not bound

CAP bound

high levels of transcription

Tutorial Case Study 2

Aim: Create a genetic variant of E. coli that can sequester and remove copper particles from the environment.

Hypothesis: The introduction of a plasmid that contains copper-sequestering proteins with the CusC promoter controlled by a signal transduction system that senses copper can produce a strain of E. coli that remove environmental copper.

Fig. 1: The signal transduction system used is two-component. The sensor is CusS and the response regulator is CusR. The tOmpC-CBP gene is the signal transduction system is acting on (target gene).

Fig. 2: The type of plasmid being used is expression plasmid (could possibly also be reporter plasmid). The selection marker is AmpR. Plasmids are self-replicating. In order to replicate, the DNA polymerase binds to PMB1 ori.

Fig. 3:

Control:

-pUC19 (empty plasmid control)

-pCC1056 with Zn2+ (negative control)

-uninduced cells in pCC1056 (a)

Treatment:

-cells induced with 0.5 mM & 1.0 mM CuSO4 (B, C) of pCC1056

Under 0.5 mM & 1.0 mM CuSO4 with copper ions will have expression of the copper binding protein. Under negative control conditions there would not have expression of copper binding protein. A lower concentration of CuSO4 promoted better copper adsorption. Expect expression of tOmpC-CBP from pCC1056 plasmid under 0.5 mM CuSO4 & 1.0 mM CuSO4 conditions.

Conclusion:

Authors reached their aim and conclusion was accepted because they the E.coli genetic variant that was created was able to remove copper particles from the environment. The plasmid introduced into E.coli was able to sense copper and remove it from the environment.

Tutorial Case Study 3

Background: Biofilms are a major component of the v.cholerae life cycle, both environmentally and during infection. Biofilms are complex environments and can house multiple organisms. Autoaggregation is when multiple bacterial cells come together to form a small cluster. Current theory is Quorum Sensing and Chemotaxis play a role in mediating autoaggregation.

Aim: To observe the effects of a E.coli on V. cholerae biofilm formation

Hypothesis: E. coli will increase the formation of a dual-species

Data:

Fig. 1: Comparison of biofilm formation by V.cholerae (strain C6706) and commensal E.coli (strain MP7) grown in monoculture or coculture (1:0.05 and 1:1). Control groups are E.coli strain MP7 and V.cholerae strain C6706. Treatment groups are C6706 + MP7 (1:0.05) C6706 + MP7 (1:1). Co-culture increases biofilm formation and when ratio of V.cholera to E.coli is increased, even more biofilm formation is observed. Data supports hypothesis overall; but can’t tell if E.coli is significantly contributing or not because error bars don’t overlap (insignificant).

Fig. 2: Autoaggregation and coaggregation of V.cholerae C6706, E.coli MG1655, pathogenic E.coli (EPEC), Δflic (flagella) or ΔfimA (pili) strains. In panel A, MG1655 and ΔfimA are E.coli strains that possess flagella. EPEC, Δflic don’t possess flagella. Flagella doesn’t promote better autoaggregation in E.coli. V.cholerae displays a higher aggregation rate compared to E.coli. V.cholerae contributes the most to improved co-culture biofilm formation and it aggregates better, but data is still not significant (error bars overlap).