a&p 151 exam 2 essay questions

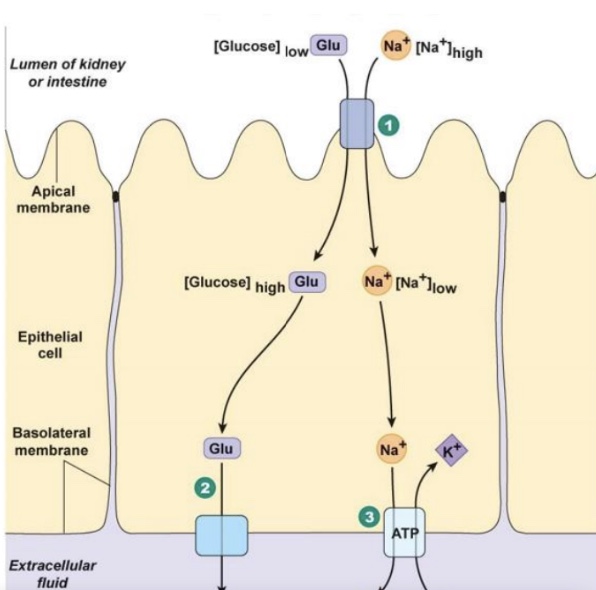

secondary active transport

facilitated diffusion

primary active transport

Can you describe the steps in the signaling that takes in a G-protein coupled receptor that acts through cyclic AMP and what is the function of acting through a second messenger system?

The signaling through a G-Protein Coupled Receptor (GPCR) that acts through cyclic AMP (cAMP) involves the following steps:

Ligand Binding: A signaling molecule (ligand) binds to the GPCR on the extracellular side, causing a conformational change in the receptor.

G-Protein Activation: The activated GPCR interacts with an associated G-protein, promoting the exchange of GDP for GTP on the alpha subunit of the G-protein.

Dissociation of G-Protein Subunits: The G-protein dissociates into the GTP-bound alpha subunit and the beta-gamma dimer, which can then influence various target proteins in the cell.

Activation of Adenylate Cyclase: The activated alpha subunit of the G-protein interacts with and activates adenylate cyclase, an enzyme located in the plasma membrane.

Production of cAMP: Adenylate cyclase converts ATP to cyclic AMP (cAMP), a secondary messenger that amplifies the signal within the cell.

Activation of Protein Kinase A (PKA): cAMP binds to and activates protein kinase A (PKA), leading to its phosphorylation of target proteins.

Cellular Response: The phosphorylation of proteins by PKA results in various cellular responses, which can include changes in gene expression, alterations in metabolism, or changes in cell behavior.

Signal Termination: The signal can be terminated by the degradation of cAMP through phosphodiesterase, which converts cAMP back to AMP, thus shutting down the pathway.

Function of Acting through a Second Messenger System:

Acting through a second messenger system, like cAMP, allows for rapid amplification of the signaling response and coordination of complex cellular processes. It enables a single ligand binding event to evoke a significant cellular response by activating multiple downstream effector proteins. This system provides versatility and allows for fine-tuning of cellular responses to various stimuli, enhancing the regulatory mechanisms within the cell and enabling precise control over physiological processes.

Need to know all the gory details of production of an action potential? What is threshold? What causes the different phases of the action potential? What are these phases called? Can you explain how an action potential propagate down the axon? Why can it only move unidirectional?

Production of an Action Potential

Threshold:

The threshold is the critical level to which the membrane potential must be depolarized in order for an action potential to be initiated. Typically, this is around -55 mV in neurons.

Phases of Action Potential: The action potential consists of several distinct phases:

Resting Phase:

The neuron is at rest, with a membrane potential of approximately -70 mV, maintained by the sodium-potassium pump (Na+/K+ ATPase) and the selective permeability of the membrane to potassium (K+).

Depolarization:

When the membrane potential reaches the threshold due to excitatory inputs, voltage-gated sodium (Na+) channels open. This results in a rapid influx of Na+ ions, causing the membrane to depolarize and the potential to rise towards +30 mV.

Repolarization:

After reaching peak depolarization, the Na+ channels close, and voltage-gated potassium (K+) channels open. K+ ions flow out of the neuron, causing the membrane to repolarize back towards the resting membrane potential.

Hyperpolarization:

The K+ channels are slow to close, resulting in an efflux of K+ that temporarily makes the membrane potential more negative than the resting potential (around -80 mV). This is also called the after-hyperpolarization phase.

Return to Resting State:

Eventually, the K+ channels close, and the sodium-potassium pump restores the resting potential.

Propagation Down the Axon:

The action potential propagates along the axon via a process called saltatory conduction in myelinated axons and continuous conduction in unmyelinated axons.

In myelinated axons, the action potential jumps between the Nodes of Ranvier, where voltage-gated Na+ channels are concentrated, significantly increasing the speed of conduction.

In unmyelinated axons, the action potential travels in a wave along the entire length of the axon, but at a slower rate compared to myelinated fibers.

Unidirectional Movement:

The action potential only propagates in one direction (from the axon hillock towards the axon terminals) because of the refractory periods that follow each depolarization phase.

During the absolute refractory period, which occurs immediately after an action potential, the Na+ channels are inactivated and cannot reopen, preventing backward propagation.

The relative refractory period follows, during which a stronger-than-normal stimulus is required to initiate another action potential, further ensuring unidirectional flow.

What is the cue for release of neurotransmitters? What proteins dock the vesicles? Can you describe the events that lead to release neurotransmitters?

The release of neurotransmitters is triggered by the arrival of an action potential at the axon terminals, which leads to a series of events:

Action Potential Arrival: When the action potential reaches the axon terminal, it causes depolarization of the membrane.

Opening of Voltage-Gated Calcium Channels: The depolarization triggers the opening of voltage-gated calcium (Ca2+) channels in the presynaptic membrane.

Calcium Influx: Calcium ions flow into the presynaptic neuron due to the higher concentration of Ca2+ outside the cell, causing an increase in intracellular calcium levels.

Vesicle Docking: Calcium ions bind to specific proteins that facilitate the docking of synaptic vesicles filled with neurotransmitters to the presynaptic membrane.

Proteins Involved: Synaptotagmin is a calcium sensor protein that, upon binding calcium, triggers the interaction between SNARE proteins (like SNAP-25 and synaptobrevin) that facilitate fusion of the vesicle with the membrane.

Vesicle Fusion and Release: The interaction of SNARE proteins leads to the fusion of the synaptic vesicle membrane with the presynaptic membrane, resulting in the release of neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft through a process called exocytosis.

Neurotransmitter Action: Once released, neurotransmitters diffuse across the synaptic cleft and bind to receptors on the postsynaptic membrane, leading to various effects depending on the type of neurotransmitter and receptor involved.

What are the different receptors that acetylcholine activate? What mechanism do they signal through? How is this neurotransmitter removed from the synaptic cleft?

Acetylcholine (ACh) activates two main types of receptors, each signaling through different mechanisms:

Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors (nAChRs):

Type: Ionotropic receptors

Mechanism: When acetylcholine binds to nicotinic receptors, these receptors open cation channels, allowing the influx of sodium (Na+) ions and a smaller efflux of potassium (K+). This leads to depolarization of the postsynaptic membrane and generates excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs).

Location: Found in the neuromuscular junction, autonomic ganglia, and parts of the central nervous system (CNS).

Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors (mAChRs):

Type: Metabotropic receptors

Mechanism: Muscarinic receptors are G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs). ACh binding activates intracellular signaling cascades through G-proteins, which can open ion channels (e.g., potassium channels) or influence second messenger systems (such as cAMP). This may lead to either excitatory or inhibitory effects on the postsynaptic neuron depending on the specific subtype of muscarinic receptor activated.

Location: Found in various tissues including the heart, smooth muscle, glandular tissue, and central nervous system, involved in diverse functions such as heart rate regulation and salivary gland secretion.

Removal of Acetylcholine from the Synaptic Cleft:Acetylcholine is removed from the synaptic cleft primarily by the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE). This enzyme hydrolyzes acetylcholine into acetate and choline, effectively terminating the signal and preventing continuous stimulation of the postsynaptic receptors. The choline can be taken back up by the presynaptic neuron for reuse in acetylcholine synthesis, while the acetate is typically metabolized elsewhere.

What is the major excitatory neurotransmitter of the CNS? Can you describe the process of long-term potentiation?

The major excitatory neurotransmitter of the Central Nervous System (CNS) is glutamate. Glutamate plays a critical role in synaptic transmission, plasticity, and overall brain function.

Long-Term Potentiation (LTP)

Long-term potentiation is a persistent strengthening of synapses based on recent patterns of activity, which is thought to be a cellular mechanism underlying learning and memory. Here is a description of the process leading to LTP:

Stimulus Induction:

LTP often begins with high-frequency stimulation of presynaptic neurons, resulting in a rapid release of glutamate into the synaptic cleft.

Glutamate Binding:

Glutamate binds to two main types of receptors on the postsynaptic neuron: N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors.

Activation of NMDA Receptors:

NMDA receptors are voltage-dependent and require both glutamate binding and membrane depolarization to open. Upon binding, they allow calcium ions (Ca2+) to flow into the postsynaptic neuron, but only if the membrane is depolarized sufficiently to remove the magnesium blockade from the receptor.

Calcium Entry:

The influx of Ca2+ through NMDA receptors is crucial, as it serves as a second messenger that initiates various intracellular signaling pathways.

Activation of Kinases:

Increased intracellular Ca2+ activates several signaling cascades, including protein kinases such as CaMKII (calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II) and PKC (protein kinase C). These kinases play significant roles in phosphorylating proteins involved in synaptic strengthening.

AMPA Receptor Trafficking:

The signaling pathways can lead to the insertion of additional AMPA receptors into the postsynaptic membrane, increasing the neuron's sensitivity to glutamate.

Structural Changes:

Over time, repeated activation of LTP can lead to structural changes, such as increased synaptic efficacy and the growth of new dendritic spines where additional AMPA receptors are located. This contributes to the long-lasting aspect of synaptic strengthening.

Maintenance of LTP:

The synaptic changes that result from LTP can be maintained for hours to days or even longer, contributing to the storage of information in the brain.

Knowt

Knowt