Week 5

Current Approaches to the Diagnosis of Depression

The criteria for a major depressive disorder (also referred to as ‘major depression’) include:

Depressed mood for more than two weeks.

Feeling depressed, sad, empty or hopeless.

Loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities (anhedonia).

Plus at least four of: weight loss/gain or decreased/increased appetite; loss of energy or excessive fatigue; moto restlessness or slowed movements; diminished concentration, ability to think, or indecisiveness; feelings of worthlessness or guilt; recurrent thoughts of death, suicidal ideation, or a suicide attempt.

DSM-V Specifiers in Clinical Diagnosis of Depression

There are extensions to the diagnosis to clarify variability such as:

Severity of depression (mild, moderate, or severe).

Number of episodes of depression (single or recurrent).

Degree of recovery between episodes (full or partial).

Depression with or without psychotic features.

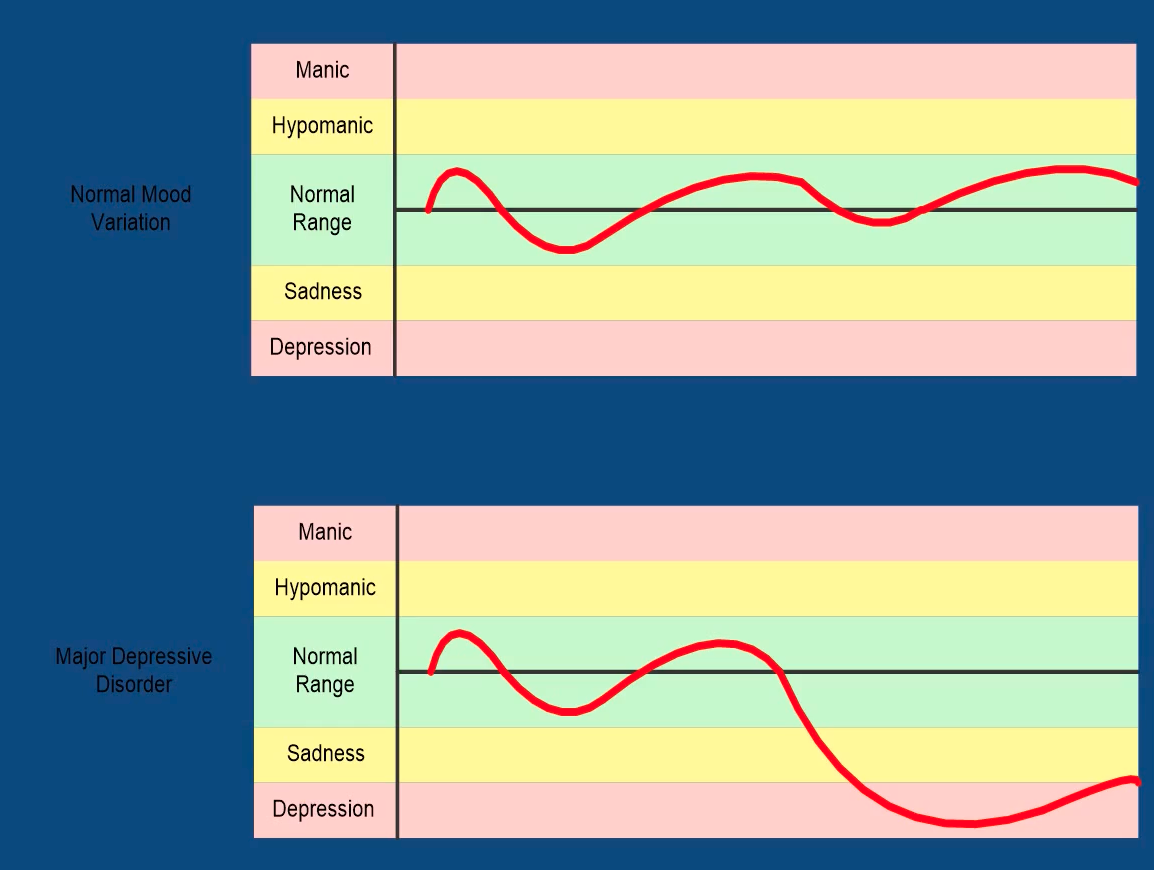

Normal Mood Variation vs Major Depressive Disorder

Types of Depressive Disorders

Major Depressive Disorder:

Depressive disorder involving one or more major depressive episodes.

Characterised by a continuous period of at least two weeks during which the individual feels depressed, sad, empty, or hopeless, or has lost interest in nearly all of their activities.

Persistent Depressive Disorder (Dysthymia):

Depressive disorder that is less severe than major depression but more chronic.

The mood disturbance and at least two other symptoms (e.g., insomnia, poor self-esteem and low energy) last for at least two years without a notable remission of symptoms.

Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder:

A depressive disorder characterised by severe and persistent irritability as evident in temper outbursts that are extremely out of proportion to the situation.

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder:

Severe form of premenstrual syndrome (PMS).

Follows a predictable and cyclical pattern.

Characterised by dysphoria, a profound sense of unease and dissatisfaction.

Symptoms occur in the late luteal phase (last two weeks) of menstrual cycle and ends shortly after menstruation begins.

To diagnose this disorder, symptoms are tracked across menstrual cycles.

The Epidemiology of Depression

In Australia 3.1% in men and 5.1% in women are diagnosed with depression over a one year period.

Women are twice as likely to experience depression as men.

Median age at onset is approximately 30 years.

High levels of anxiety and substance abuse are associated with an increased risk of developing depression in young people.

Other risk factors: a history of depression, ongoing family conflict, a history of sexual or physical abuse, residing in a rural area, being of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent, and having a parent with a psychological disorder.

The Epidemiology of Depression - Recovery and Relapse

Approximately 50% of those with a depressive disorder will recover within six months following treatment.

Many who recover from a first episode will have another episode within 5 years.

Earlier age of onset, continued experience of some symptoms, multiple prior depressive episodes, ongoing life stressors, and history of depression in family members increases the risk of relapse.

Problems Associated with Depression

Increased risk of suicide attempts and death by suicide.

Rate of suicide in the community from depressive disorders is 3.5%.

Higher rate for male suicides (6.9%), than female suicides (1.1%).

Impaired social and occupational functioning.

Co-morbidity with anxiety disorders.

Increased physical health problems.

The Aetiology of Depression

Biological Factors:

Genetic component - a family history increases the risk of depression by two to three times.

Neurotransmitter imbalances are implicated in depression.

The main neurotransmitters implicated in depression are serotonin, noradrenaline (norepinephrine) and dopamine, which are also involved in the regulation of sleep cycles, motivation and appetite.

Potential structural or functional abnormalities in the pre-frontal cortex, hippocampus, anterior cingulate cortex, and the amygdala.

Environmental Factors:

Stressful life events (acute: financial disaster; chronic: living with an abusive partner) can act as causal triggers.

Growing up in a hostile, disruptive, and violent family environment increases the risk of depression.

Environmental risks usually interact with biological and learnt psychological vulnerabilities to trigger depression.

It is possible to reduce the impact of stressful life experiences by increasing social support.

Psychological Factors:

Including cognitive theories, behavioural theories, and psychoanalytic theories.

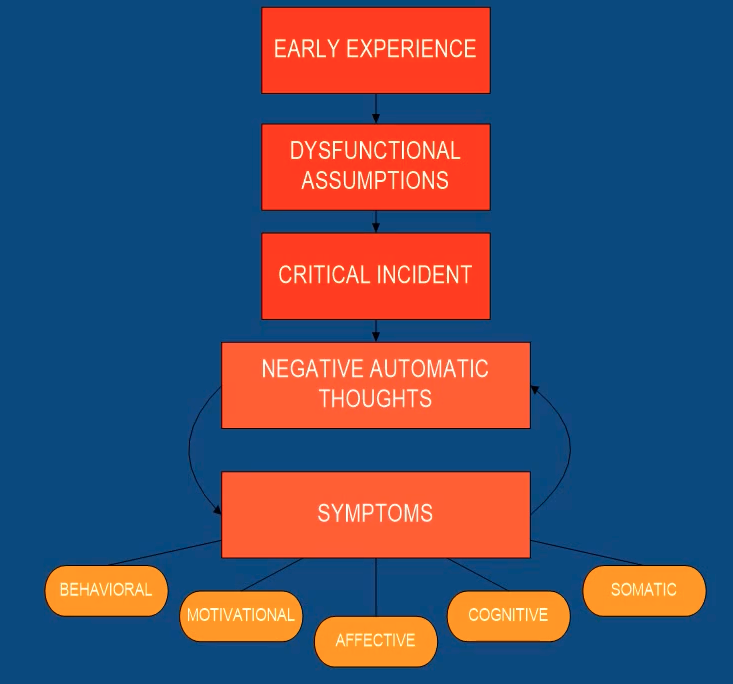

Cognitive Theories: depressive attributional styles, seeing negative events due to internal, global, and stable factors. Beck’s negative cognitive triad, depressed people hold a negative view of the self, the world, and the future, and this view is maintained by cognitive distortions.

Behavioural Theories: focus on contingencies associated with depressed and non-depressed behaviours. Highlights the role of poor coping skills.

Psychoanalytic Theories: depression is a form of pathological grief.

Social Factors:

Interpersonal difficulties such as high expressed emotion (relationships involving hostility, high levels of criticism, and over involvement) have been linked to depression.

Lack of intimate relationships, particularly a risk factor for women.

Protective Factors:

Good interpersonal skills, high levels of family cohesion, being connected with one’s community, achievement in a valued pursuit, optimism and low anxiety, openness to experience and effective coping skills.

Beck’s Cognitive Model of Depression

Depression comprises automatic negative thoughts.

Treatment is slowly changing such thoughts and assumptions.

The Treatment of Depression

Pharmacological and Physical Approaches:

Medication.

Bright light therapy (treatment for seasonal affective disorder).

Electroconvulsive therapy (treatment for severe depression).

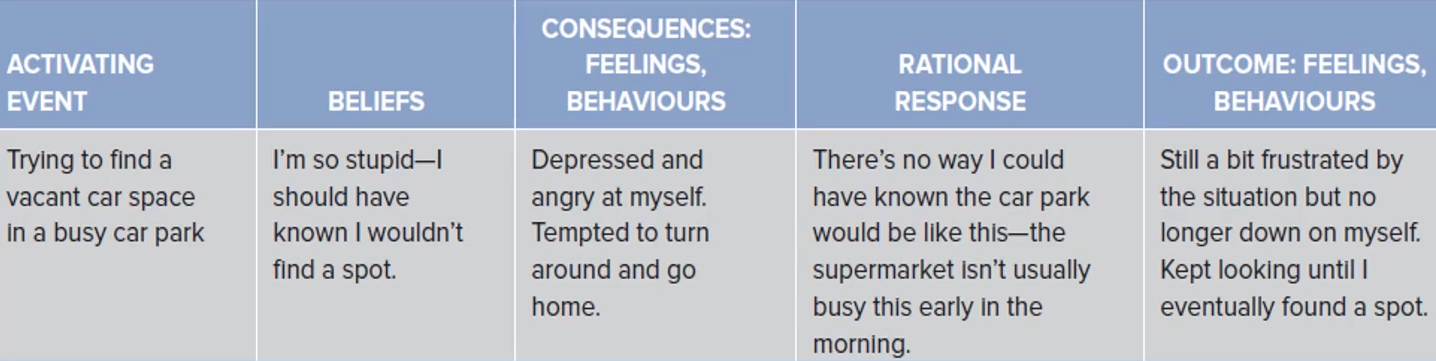

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Approach:

A common exercise in CBT is to ask clients to record the thought that trigger negative mood and behaviours and then to replaces these thoughts with more realistic ones that are supported by evidence.

Interpersonal Psychotherapy:

Focuses on interpersonal problems that may be related to the onset and/or maintenance of the depressive episode.

Psychodynamic Therapy:

Enhance insight about the repetitive conflicts maintaining the depressive episode.

Relapse Prevention

Most common method is antidepressant medication.

Continue active phase of psychological treatment (e.g., CBT and IPT).

Plan how to cope with future triggers to depressed mood.

Develop a plan for how to respond if symptoms re-emerge.

Treatments specifically for relapse include:

Wellbeing Cognitive Therapy

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy

Preventative Cognitive Therapy

The Prevention of Depression

Most preventative interventions have a CBT or interpersonal focus.

They teach cognitive, interpersonal, and coping skills; are most effective when the target group has some risk of developing depression due to family history, pre-existing symptoms, or an adverse environmental fact.

Some programs are aimed at all members of a population, regardless of pre-existing skills level.

Displays inconsistent effects and requires substantial resources to reach large numbers.

Internet delivery of treatment and prevention may be promising.

The History of Bipolar Disorder

For most of history, mania and depression were viewed as seperate illnesses.

During the late nineteenth century, mania and depression began to be considered as a single entity.

Karl Leonhard (1957) argued that the term ‘manic depressive insanity’ was too inclusive, and coined the term ‘bipolar disorder’.

An Australian psychiatrist, John Cade, discovered lithium as an effective treatment for mania - which revolutionised the treatment of bipolar disorder.

The Diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder

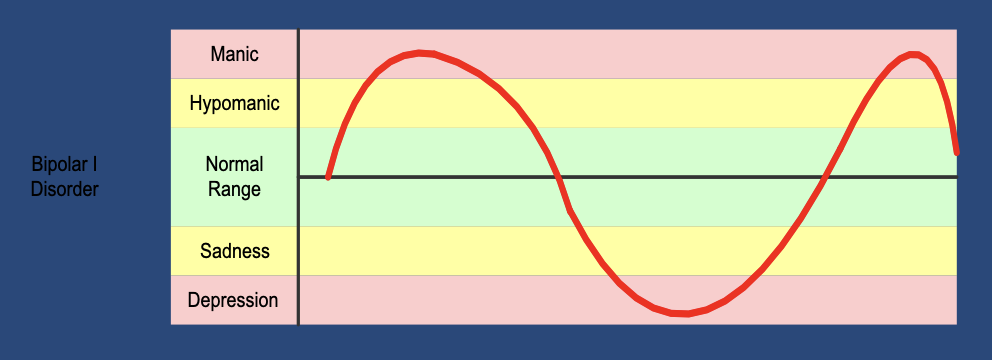

Bipolar disorders embrace a spectrum of disorders including bipolar I, bipolar II, and cyclothymic disorder.

These three disorders all share symptoms of pathologically elevated mood.

These elevated mood states are referred to as ‘manic’ and hypomanic episodes’.

Manic and Hypomanic Episodes

A manic episode is defined by the DSM-V as elevated, expansive or irritable mood with increased goal-directed activity or energy for at least 1 week, plus at least 3 of the following:

Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity.

Sleep disturbance - decreased need for sleep.

Pressure of speech.

Flight of ideas.

Distractibility.

Heightened activity.

Risk taking.

A hypomanic episode only requires symptoms to be present for at least 4 days, and symptoms tend to be less severe.

Types of Bipolar Disorders

Bipolar I Disorder:

Presence of one or more manic episodes.

Major depression may be present but is not required for diagnosis.

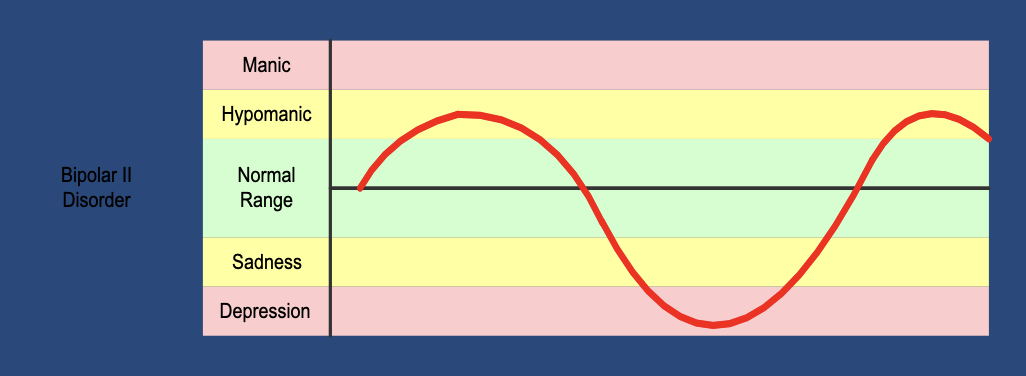

Bipolar II Disorder:

At least one episode of major depression.

At least one period of hypomania.

Must not have had a manic episode.

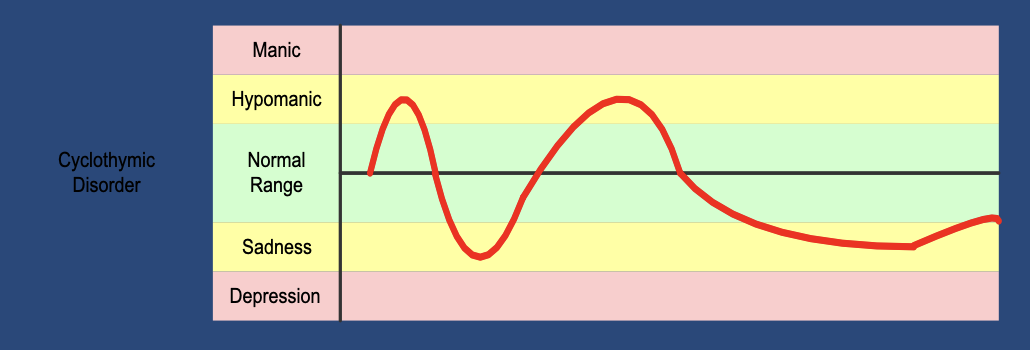

Cyclothymic Disorder:

Symptoms are less severe but more chronic than bipolar I and II.

Numerous periods of elevated and depressed mood, but not severe enough to meet the criteria for hypomanic, manic, or major depressive episodes.

Under and Over Diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder

Under Diagnosis:

Patients with bipolar disorder may be misdiagnosed as having schizophrenia (men) or major depressive disorder (women).

Misdiagnosis as schizophrenia may be because of similarities between psychotic features of acute mania and schizophrenia (e.g., delusions and hallucinations).

Misdiagnosis as major depressive disorder may be because past episodes of hypomania and mania are not adequately explored by the clinician.

Over Diagnosis:

Brief periods of elevated mood may be wrongly diagnosed as hypomania.

Common for those with borderline personality disorder.

Could mean inappropriate use of mood-stabilising medications.

Misdiagnosis of Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder is frequently misdiagnosed, presenting a significant challenge in mental health care.

This in part, may be due to the increased awareness of certain disorders.

Individuals often seek out information that confirms their existing beliefs or concerns, leading them to perceive symptoms that align with their expectations.

Approximately 69% of patients with bipolar disorder are misdiagnosed initially.

Approximately 40% are initially diagnosed with unipolar depression.

Many others with borderline personality disorder, histrionic personality disorder, or adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Causes of Misdiagnosis

Lack of insight (e.g., It was not mania, it was great!).

Lack of available information (e.g., I do not remember anyone telling me that I was manic).

Lack of appropriate assessment tools used (e.g., The 13-item mood disorder questionnaire effectively assesses bipolar disorder; however, depression inventories do not).

The overlap in apparent signs with other disorders (e.g., Many health workers are confused at the differences between borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder).

The high percentage of comorbidity with other disorders (e.g., You could have bipolar disorder with comorbid personality disorder and unipolar depression).

Prevalence, Age of Onset, and Course of the Disorder

Lifetime prevalence of 1.3%, and a annual prevalence of 0.9%.

Men and women are equally likely to meet the criteria for bipolar I disorder, women are more likely to meet the criteria for bipolar II disorder.

Median age of onset is approximately 25 years.

The majority of time is typically spent in depressive episodes rather than in manic or hypomanic phases.

High rates of relapse are made worse by poor medication compliance.

Comorbidities of Bipolar Disorder

Anxiety Disorders:

Nearly one in two individuals with bipolar disorder have a diagnosis of at least one anxiety disorder.

Substance Misuse:

Reported in 39% of people with bipolar disorder.

Social and Economic Costs:

Those with bipolar disorder are almost 5 times more likely to have disrupted relationships.

Suicide:

Suicide rate is nearly 15 times that of the general population.

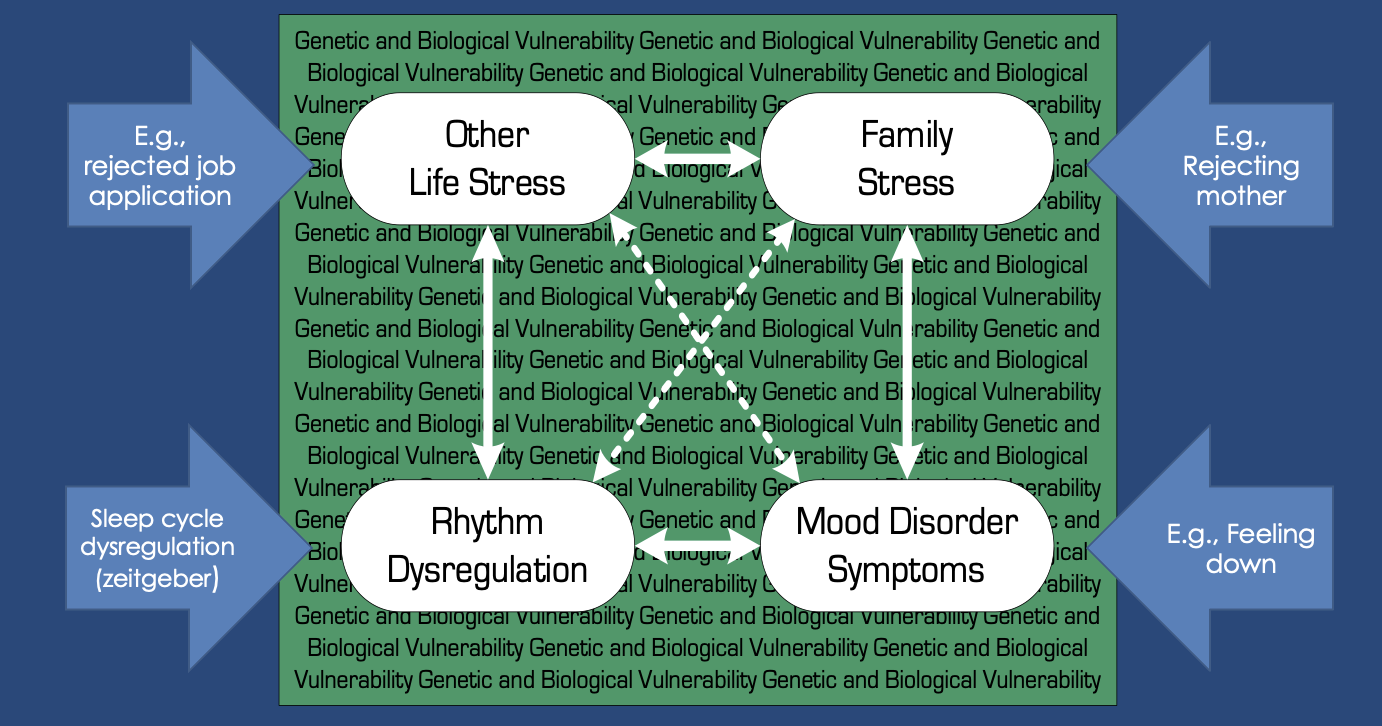

The Aetiology of Bipolar Disorder

Biological Factors:

Twin studies suggest a heritability rate of approximately 85%.

Psychological Factors:

Greater negative beliefs about oneself and the world, temperamental tendencies.

Stressful Life Events:

Diathesis Stress Model: disorders result from interaction between underlying vulnerability and stressful life events.

Goal Dysregulation Model: mania is the result of excessive goal engagement.

Measures of States and Traits related to Bipolar Disorder:

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale; Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale 24; BIS/BAS Scales; Response Style Questionnaire; Internal State Scale.

Model of Bipolar Disorder

The Treatment of Bipolar Disorder

Pharmacological Approaches:

Mood stabilising medication.

Psychological Approaches:

Psychoeducation: identify signs of relapse, medication adherence, and minimise risk.

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy: foster self-efficacy.

Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy (IPSRT): reduce disruption in daily routines and sleep/wake cycles.

Family Interventions: improve family knowledge, communication, and problem-solving skills.

Hospitalisation: when patients are suicidal or psychotic.

New Developments: mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, internet based treatments, focus of quality of life, self-management for bipolar disorde focusing on wellness and personal recovery.