Chapter 6 - Pain Assessment

Notes on Pain Transmission

Peripheral Nervous System (PNS)

Types of Nerve Fibers:

A-delta fibers:

Large, myelinated fibers.

Conduct pain impulses rapidly.

Pain described as sharp or stabbing.

C fibers:

Smaller, unmyelinated fibers.

Conduct pain impulses slowly and diffusely.

Pain described as achy and ongoing, even after the stimulus is removed.

Nociceptors:

Specialized peripheral A-delta and C fibers that carry pain signals to the CNS.

Substance P:

Released by C fibers from nerve endings.

Accelerates the transmission of the pain stimulus along the pathway.

Bradykinin:

Released at the site of injury from damaged tissue.

Causes continued irritation at the injury site.

Central Nervous System (CNS)

After pain stimuli transfer to the CNS, they synapse in the spinal cord.

Gate Control of Pain:

Pain transmission depends on the balance between:

Pain-facilitating impulses and substances.

Pain-blocking impulses and substances.

If facilitating impulses dominate, the pain signal continues. If blocking impulses dominate, the pain signal stops.

Pain Signal Pathway:

Signal travels from the spinal cord into the lateral spinothalamic tracts.

Moves to the thalamus and then the limbic system, where pain-related emotions are produced.

Finally reaches the cerebral cortex, where the sensation is recognized as pain.

Speed: The entire process occurs in milliseconds.

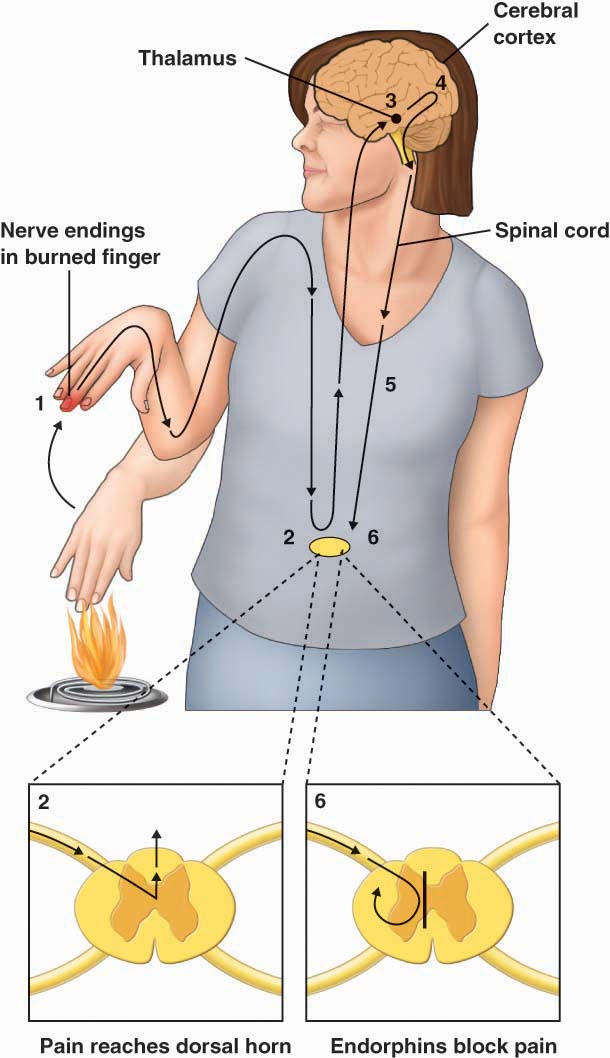

Notes on Pain Transmission (Figure 6.1)

Pain Initiation:

Pain begins when nerve endings detect an injury (e.g., a burnt finger).

Sensitization of Nerve Endings:

Substances released at the injury site:

Substance P

Bradykinin

Prostaglandins

These substances sensitize the nerve endings, helping transmit pain signals toward the brain.

Signal Transmission to the Spinal Cord:

Pain signals travel as electrochemical impulses along nerves to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.

The dorsal horn collects pain signals from across the body.

Signal Transmission to the Brain:

From the spinal cord, pain messages are sent to the thalamus and then to the cortex, where they are processed and recognized.

Pain Relief Initiation:

Signals from the brain descend via the spinal cord to manage the pain response.

Chemical Pain Relief:

Endorphins are released in the dorsal horn to diminish pain messages.

Key Substances in Pain Transmission:

Substance P:

Used by peripheral nerve endings and at synaptic junctions to transmit pain signals.

Glutamate:

Neurotransmitter responsible for communication between the peripheral and central nervous systems.

Activates pain receptors, intensifying and prolonging persistent pain.

Simple Notes on Serotonin and Pain

What Serotonin Does:

Serotonin helps block pain by stopping glutamate from being released.

This reduces how much pain is sent through the nerves.

Medicines That Use Serotonin:

Doctors may give medicines to increase serotonin levels to help with long-term pain.

These medicines include:

Tricyclic antidepressants

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

Simple Notes on Gate Control Theory and Nociception

Gate Control Theory

What It Is:

The body reacts to pain by either:

Opening a "gate" to let pain through.

Blocking the pain to stop it from reaching the brain.

How Pain Travels in the Gate Control Theory:

Pain starts when a painful stimulus causes a nerve to open the "gate."

The pain travels from the nerve to the spinal cord.

The pain reaches the brain (limbic system and cortex), where it’s recognized as pain.

The brain sends signals back to the body to react to the pain.

Substances Affecting Pain:

Pain-Facilitating Substances: Help pain travel. Examples:

Substance P

Bradykinin

Glutamate

Pain-Blocking Substances: Help stop pain. Examples:

Serotonin

Opioids

GABA

Nociception (How We Feel Pain)

What It Is:

Nociception is how the body senses pain through special receptors called nociceptors.

These receptors sense pain from things like heat, pressure, or chemicals from injuries.

Four Steps in Nociception:

Transduction: Pain-causing stimuli (like heat or pressure) create a signal that the body can feel.

Transmission: The pain signal travels from the body to the spinal cord and then to the brain.

Perception: The brain understands the signal as pain.

Modulation: The brain can help block or change the pain signal at the spinal cord level.

Chronic Pain:

Sometimes, pain can keep going even when there’s no injury. This can happen because the body changes how it sends or feels pain.

Clinical Significance

Pain Perception: How pain is felt is important, and there are many ways to manage pain without using strong medicines (like opioids).

Simple Notes on Types of Pain

Pain Definitions:

Pain is an unpleasant feeling related to tissue damage or the potential for it.

Acute pain: Short-term pain caused by injury or surgery.

Chronic pain: Long-term pain that lasts beyond the normal healing period.

Types of Pain:

Visceral pain: From internal organs (e.g., crampy or gnawing).

Somatic pain: From muscles, bones, and joints (e.g., sharp pain).

Cutaneous pain: From the skin (e.g., burning or sharp).

Referred pain: Pain felt somewhere else in the body (e.g., heart pain felt in the arm).

Phantom pain: Pain in a body part that’s no longer there (e.g., after an amputation).

Special Types of Pain:

Neuropathic pain: Pain from nerve damage (e.g., diabetic pain).

Nociplastic pain: Pain with no clear cause, often from changes in the nervous system (e.g., fibromyalgia).

Chronic Pain Facts:

One in five people experience chronic pain.

Can cause lost income, medical costs, and affect daily life.

Important Concepts:

Neuronal plasticity: When the nervous system changes how it works, often making pain worse.

Peripheral sensitization: When touch or pressure starts to feel painful because of inflammation.

Central sensitization: When pain continues even after the injury has healed.

Pain Management:

Windup: When repeated pain increases the sensitivity to pain in the body.

Treatment focus: Managing pain and preventing it from becoming chronic.

Simple Notes on Pain in Older Adults and Cultural Variations

Chronic Pain in Older Adults:

About 25% to 40% of adults over 65 have chronic pain.

More common in women, older adults (over 85), and those with lower body weight or multiple pain locations.

Pain is not a normal part of aging.

Some older adults may have trouble telling if pain is from surgery or a previous condition.

Aging doesn't lower pain sensitivity, though many think it does.

Challenges in Treating Pain in Older Adults:

Older adults may experience more side effects from pain medicine, especially opioids.

Healthcare providers may under-treat pain to avoid these side effects.

When assessing pain in older adults:

Consider if they have hearing or vision problems.

Use clear language and provide instructions in ways they can see or hear.

Allow extra time for responses.

Cognitive issues (e.g., dementia) make pain assessment harder, but people with these issues still feel pain.

Behavioral signs like grimacing or restlessness may be used to assess pain but aren’t always accurate.

Cultural and Racial Differences in Pain:

There is no proof that race affects pain sensation, but minorities often receive less pain treatment.

Biases may cause healthcare providers to rate pain lower or give less medication to minority patients.

Sex Differences in Pain:

Women’s primary sensory nerves are more sensitive, making them experience pain differently than men.

Women may have more pain, especially in conditions like fibromyalgia or irritable bowel syndrome.

Women are also more likely to show pain and be diagnosed with chronic pain.

Men are expected to be less emotional about pain, which can affect how their pain is treated.

Important Considerations:

Be aware of unconscious biases in pain assessment, such as judging someone’s pain based on their appearance.

Women’s pain is sometimes taken less seriously than men’s pain.

Work closely with patients and families to create pain management goals that consider gender and cultural differences.

Key Points for Assessing and Managing Pain

Urgent Assessment:

Chest Pain:

Must be treated immediately, as it may indicate a myocardial infarction (heart attack). Each passing minute can worsen the condition.

Severe Headache:

If a patient reports the “worst headache of my life,” this may indicate a cerebral hemorrhage, requiring emergency intervention.

Acute Pain Signs:

Symptoms like high BP, tachycardia, diaphoresis (sweating), shallow respirations, and facial grimacing indicate acute pain. Investigating the cause is crucial.

Safety Alerts:

Lack of Pain in Acute Injury:

If pain is absent in cases of severe injury (e.g., spinal cord injury), it might signal a serious issue like a complete cord severance or impaired circulation, which could result in loss of a limb.

Undertreated Acute Pain Risks:

Untreated or undertreated acute pain can lead to chronic, harder-to-treat pain conditions, such as complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS).

Patient Education:

Pain Management:

Teach patients that managing pain early helps prevent the development of chronic pain and improves overall health.

If a patient refuses medication, investigate reasons such as concerns about side effects (e.g., nausea, constipation) or difficulty accessing medication.

Pain Assessment Approach:

Subjective Reporting:

Pain is what the patient says it is. Always accept the patient's pain report, even if it seems inconsistent.

Pain Assessment Tools:

Numeric Pain Intensity (NPI) Scale (0–10) to quantify pain.

OPQRST or OLDCARTS mnemonics to guide the assessment:

O: Onset

P: Provocative/Palliative

Q: Quality

R: Region/Radiation

S: Severity

T: Timing

L: Location

D: Duration

C: Character

A: Alleviating/Aggravating

R: Radiation

T: Timing

S: Severity

Key Symptoms and Questions for Pain Assessment:

Location:

Ask the patient where the pain is and if it radiates (e.g., leg pain with low back pain).

Duration:

How long has the pain lasted? If it persists for 3–6 months, it is chronic.

Intensity:

Use the NPI scale (0–10) or terms like mild, moderate, or severe if the numeric scale isn't suitable.

Quality/Description:

Let patients describe the pain in their own words (e.g., burning, sharp, dull). Specific terms like "tingling" or "burning" may indicate neuropathic pain.

Aggravating/Alleviating Factors:

Ask about things that worsen or relieve the pain (e.g., heat, cold, activity).

Pain Management Goal:

Understand the patient's expectations (e.g., what pain level is acceptable for them).

Functional Goal:

For chronic pain patients, understand how the pain affects daily activities (e.g., walking, self-care) and set functional goals to measure the effectiveness of treatments.

Common Pain-Related Conditions:

Neuropathic Pain Indicators:

Descriptors like “burning,” “tingling,” or “pins and needles” are common in neuropathic pain, often seen in conditions like CRPS.

Neuropathy or CRPS:

For patients with a history of surgery or injury, watch for symptoms like skin changes, swelling, or temperature sensitivity, which could indicate CRPS.

Clinical Significance:

Proper and consistent pain assessment is essential to provide effective treatment and avoid complications from chronic or inadequately treated pain.

Pain Assessment Tools: One-Dimensional vs. Multidimensional

One-Dimensional Pain Scales

These scales focus exclusively on measuring pain intensity. Although simple, they are reliable and valid for assessing the effectiveness of interventions such as medication.

Numeric Pain Intensity Scale (NPI):

Patients rate their pain on a scale of 0 to 10:

0: No pain

10: Worst possible pain

Pain Levels:

Mild Pain: 1–3

Moderate Pain: 4–6

Severe Pain: 7–10

Clinically significant improvement: A 30% reduction or a 2-point decrease in pain intensity (e.g., from 9/10 to 6/10).

Key principle: Accept the patient’s reported score, as pain is subjective.

Visual Analogue Scale (VAS):

A 100-mm line with “no pain” at one end and “worst possible pain” at the other.

Patients mark the line at the point that reflects their pain level. The distance (e.g., 70 mm) is converted to a 0–10 scale.

Advantages: Simple and ideal for patients who are cognitively alert but unable to verbalize.

Limitations: Requires a paper copy, and older adults may struggle with precision in marking.

Multidimensional Pain Scales

These tools evaluate not only pain intensity but also behavioral, affective, and functional aspects of pain. They are especially useful for assessing chronic pain, oncology pain, and complex conditions.

Brief Pain Inventory (BPI):

Originally designed for cancer pain but also effective for chronic non-malignant pain.

Can be administered as an interview or self-reported.

Includes:

Pain intensity: Worst, least, average, and current pain in the past 24 hours.

Body diagram: To locate pain.

Functional assessment: Impact on activity, mood, sleep, relationships, work, and enjoyment of life.

Medication efficacy: Relief percentage and treatments used in the past 24 hours.

Limitation: Patients must relate the questions to their pain experience.

McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ):

Includes:

Verbal descriptors for sensory pain (e.g., aching, cramping, burning).

A Visual Analogue Scale.

A Present Pain Intensity rating combining words and numbers.

Helps identify pain character, which can assist in diagnosing the cause (e.g., stabbing pain may indicate lung involvement).

Limitations:

Scoring the verbal descriptors can be complex.

Translating descriptors for different languages and syndromes can be challenging.

Pain, Enjoyment, and General Activity (PEG) Tool:

A 3-question scale designed to measure:

Pain intensity.

Enjoyment of life.

Impact on general activity.

Responses are summed and averaged to give a PEG score.

Recommended by the CDC for primary care and easily integrated into electronic medical records.

Key Takeaways:

One-Dimensional Tools are quick and reliable for measuring pain intensity.

Multidimensional Tools provide a holistic view of the pain experience, including its impact on functionality and emotional well-being.

Choosing the appropriate tool depends on the patient’s condition, ability to communicate, and the clinical setting.

Knowt

Knowt