Child and Adolescent Offending

Introduction

- Developmental approaches to child and adolescent delinquency emphasise the role of independent and psychological factors in the onset of delinquency, as well as the importance of early risk and protective factors in the comprehension of future delinquency.

- The age–crime curve is a crucial phenomenon in the study of young offenders, with the overall rate of offending increasing in late adolescence and gradually decreasing in the twenties.

- Factors such as age of commencement, frequency, flexibility, seriousness, longevity, and desistance characterise criminal careers.

- The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child defines a child as "every human being under the age of 18 years, unless the law applicable to the child provides for earlier attainment of majority."

- The legal age limitations adopted by juvenile courts differ from country to country.

- In England and Wales, those under the age of 18 are generally referred to as juveniles, however a distinction is frequently drawn between minors (those under 14) and young persons (age 14-16).

- The age of criminal liability varies globally between 6 and 18, and is 10 in England and Wales.

- International comparisons of adolescent justice policy and practise have examined parallels and differences, but a localised perspective is required to comprehend the cultural, legal, and historical evolution of youth justice.

Characteristics and Risk Factors

Age

- Age–crime curve: It is a graphical representation of the crime rate by age, whereas the age distribution of offence frequency is a histogram of all offenses perpetrated by each age group among offenders.

- Age–crime curves reflect the amount of crimes a person commits from one year to the next, whereas the age distribution of crime concentrates on measures of central tendency, dispersion, and skew.

- A young age of onset is indicative of multiple subsequent offences and a lengthy criminal career. Co-offending decreases steadily with age and is more prevalent in burglary and robbery.

Individual Factors

- Due to their independence and individuality, adolescents are more inclined to participate in dangerous behaviour than adults.

- In 2016, the rate of juvenile delinquency per 100,000 population aged 15 to 17 years was four and a half times that of adults aged 21 or older.

- However, the majority of adolescents "outgrow" risky behaviours, and only a minority with additional risk factors persist in antisocial or criminal behaviour.

- Latest data from the Edinburgh Study of Youth Transitions and Crime indicate that 56% of children had fully ceased committing crimes by the age of 18, rising to 90% by the age of 24.

Family Factors

- Childhood and adolescent family environments are connected with antisocial behaviour and delinquency.

- Researchers have utilised cohort follow-up to examine the onset and development of delinquent and criminal behaviours.

- The largest cohort study on the growth of delinquency and crime in the United Kingdom revealed that convicted adolescents were more likely to experience poor parenting, harsh or irregular discipline, neglectful parental attitudes, parental conflicts, and lax supervision during their childhood.

- On a personal level, it was determined that they had low IQ, poor focus, were hyperactive, and had a low level of schooling.

- In a previous study conducted in Newcastle, United Kingdom, it was discovered that children with a forensic history were exposed to poor physical and home care, as well as poor parenting, when compared to children without a forensic history.

- A more recent study undertaken for the Home Office indicated that 48% of youngsters participating in "serious violence-linked behaviours" came from "low-class" homes, whereas just 15% were from a "high-class" background.

School Factors

- Positive interpersonal interactions outside the family, strong academic accomplishment, positive attitudes towards authority, and effective use of leisure time are protective variables that help delinquents and juvenile offenders avoid reoffending, according to research.

- In terms of crime and delinquency, 10% of English schoolchildren aged 13 to 15 reported being in problems with the police, while 24% claimed having friends who were at least "occasionally" in trouble.

- Both groups were also more likely to be victims of crime at school or on the way to or from school.

Media

- Browne and Hamilton-Giachritsis (2005) discovered that young offenders favour violent media entertainment, which can affect their attitudes and behaviour and increase their likelihood of committing a violent crime.

- This tendency was noticed more often among adolescents from abusive families.

- Violence in media entertainment has been cited as one of the reasons for the rise in knife crime in the United Kingdom, and it has been suggested that the rise in the number of adolescents who view pornographic content on the internet may be linked to an increase in sexual offences committed against their peers.

Inappropriate Sexual Behaviour

- At least one-third of adult sex offenders committed their first sexual assault as adolescents, according to research.

- Gerhold et al. (2007) examined 12 studies of sexual recidivism among identified adolescent sex offenders with a mean follow-up period of 15 years.

- Skuse and colleagues (1998) discovered that one in eight sexually abused adolescent boys are becoming sexual offenders as a result of experiencing and/or witnessing consensual incest violence and discontinuing care.

Childhood Victimisation

- Childhood victimisation is strongly linked to poor parenting and a chaotic family environment, making it a common factor in the backgrounds of children who commit crimes.

- Four out of five young offenders in secure housing were found to have experienced some form of abuse or neglect as children.

- 30–60% of children of female intimate partners who experience domestic violence and abuse are also maltreated, and up to 80% have witnessed domestic assaults.

- Multiple victimisation was associated significantly with the most severe internalising and externalising problems, particularly in the presence of sexual abuse.

- A cohort study of children in the general population of the United States revealed that the trauma impact of multiple victimisation (poly-victims of six or more incidents) was significantly higher.

- 14% of English schoolchildren aged 13 to 15 were found to be multiple victims, and these adolescents were more likely to be delinquent and known to the police.

Protective Factors and Resilience

- Due to its emphasis on risk and definitional issues, protective factor study has been criticised as insufficient.

- Viljoen et al. (2020) highlight the significance of examining protective factors, which are defined as positive strengths or qualities that decrease the probability of offending, because this enhances risk assessments, provides a more balanced viewpoint, and increases a young offender's motivation to change.

- Farrington (1995) discovered that boys without parents or siblings with a history of criminal activity and boys who prevented interaction with other boys in the neighbourhood were less likely to engage in delinquent and criminal behaviour.

- McKnight and Loper (2002) discovered that experiencing sexual abuse and being raised by single parents were major risk factors for delinquency and offending.

- Resilience factors such as perceiving teachers as fair and feeling trusted, loved, and wanted by parents could discern adolescent females who noted high level of delinquency from those who revealed low level of delinquency with 80% accuracy.

Theoretical Explanations

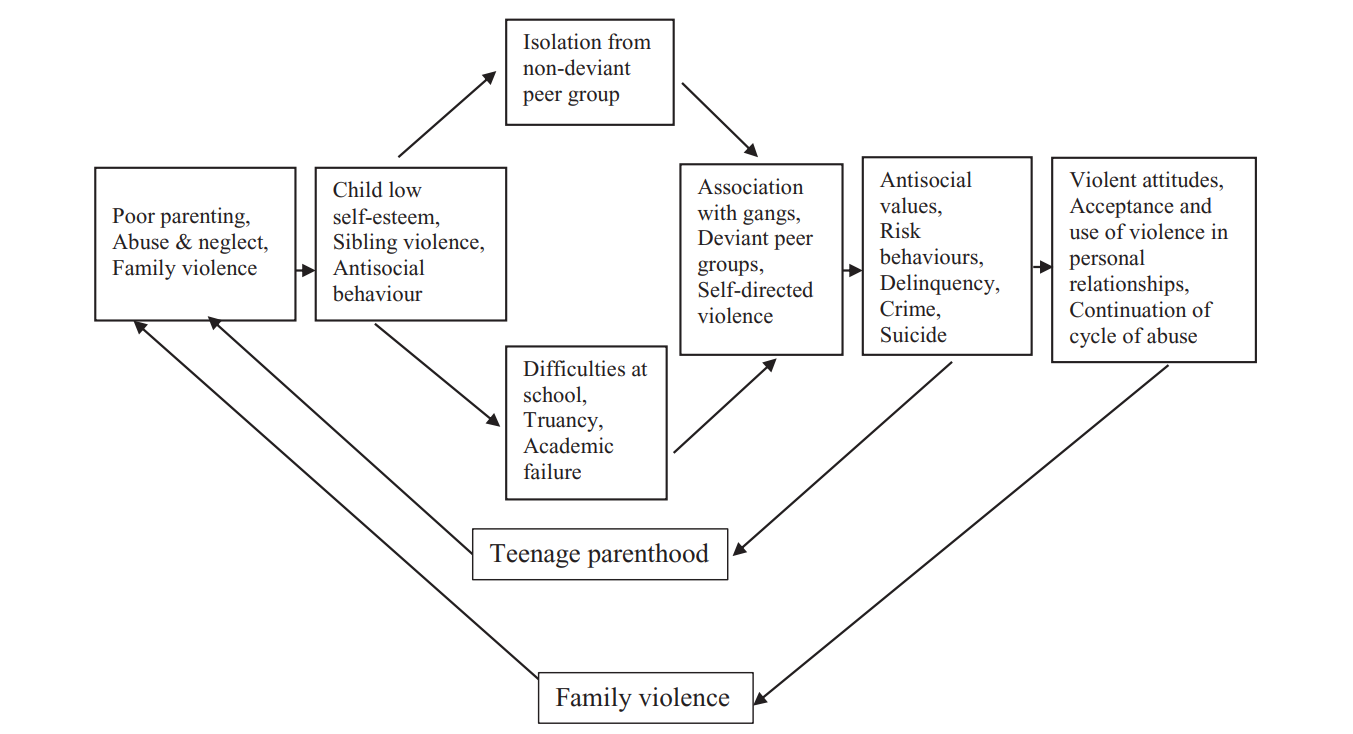

From a social-interactional standpoint, Patterson et al. (1989) proposed an explanation for the growth of antisocial behaviour.

- This concept argues that parents and carers do not properly address coercive or disrupting behaviour in young children.

- Moreover, children can learn deviant and disruptive behaviour through direct personal experience or by seeing other family members.

Children with aggressive behaviours and low social skills are prone to experience peer rejection upon starting school.

- Growing up in a chaotic and/or unorganised family can affect concentration and adherence with educational tasks, which can hinder learning and increase the likelihood of academic failure.

Attachment theory is a regularly utilised framework for describing the developmental pathways or trajectories of many outcomes.

Around two-thirds of children are said to receive sensitive and consistent parenting, build secure emotional attachments, and learn to evaluate their social surroundings positively.

- However, due to insensitive and inconsistent parenting, one-fifth of children develop an insecure/avoidant sentimental relationship.

Children from the remaining 14% of households who are abusive, negligent, or disorganised are highly prone to develop insecure/anxious emotional bonds.

- This can result in a negative self-perception and a negative view of others, which inhibits the development of trust and empathy for others and normalises violence.

According to Moffitt's developmental theory, there are two types of offenders: limited adolescents and persistent adults.

Sampson and Laub's theory of the life course emphasises on the evolution of informal social control, such as social ties to family, friends, school, and the workplace.

- Farrington (2010) desdcribed this as a series of crimes perpetrated at different ages that has a beginning (start), duration, and end (desistence).

- Peek onset occurs between the ages of 13 and 16 and is connected with the previously identified risk factors.

Shepherd et al. (2016) discovered that those who did not reoffend were more likely to be involved in prosocial activities, to have positive attitudes towards intervention and authority, and to demonstrate a strong commitment to education at the time of assessment.

Britt (2019) argues that a criminal career is somewhat a-theoretical and is instead a data-driven approach that focuses on various statistical associations that helped to identify risk and protective factors.

Intervention

- In 2018, the British government adopted a "child first, offender second" model, which focuses on the individual's personal circumstances and needs to assist them in enhancing their life situation.

- This is a shift from the alternative viewpoint that considers juvenile offenders to be "depraved" children capable of committing evil and wicked acts.

- The justice method relies on culpability and responsibility and focuses on a young person's behaviour in order to prevent future offences.

- Three stages or levels can be used to describe interventions: primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention.

- Included in primary prevention projects are informational pamphlets or summer activities, universal school initiatives, and curricula that take a cognitive-behavioral strategy to improve communication skills, conflict resolution, social skills, and resistance to negative peer pressure.

- All age groups have been found to benefit from school interventions that reduce antisocial behaviour and conduct problems.

- Secondary prevention services target "at-risk" children in order to provide interventions that mitigate risk factors that could lead to violence or potential harm.

- Numerous intervention programmes are family-centered and provide parenting intervention to families with at-risk children.

- Webster-Stratton and her colleagues developed video-based behavioural parenting interventions for parents in the United States whose children displayed conduct problems.

- In the Netherlands, the Utrecth Coping Power Program provides cognitive-behavioral intervention for children exhibiting disruptive behaviours and behaviours in children for their parents.

- In the United Kingdom, there has been an increase in the adoption of a trauma-informed "child first" approach in interagency collaboration.