sac 1

the distinction between summary offences and indictable offences

· Summary offences are minor criminal offences heard in the Magistrates’ Court and are contained in the Summary Offences Act 1996 (Vic). A hearing takes place in the magistrates’ court rather than a trial and these crimes include disorderly conduct and minor assault.

· Most offences in Victoria are Summary offences. The majority of crimes are heard in the Magistrates’ Court

· Indictable offences are serious criminal offences found in the Crimes Act and heard by a judge and a jury if the accused pleads not guilty in the County or Supreme Court of Victoria. Final hearings are known as trials and crimes include homicide and drug trafficking.

· As a general rule, offences in the Crimes Act 1958 (Vic) are indictable offences unless the offence is stated in the Act to be a summary offence

key principles of the criminal justice system, including the burden of proof, the standard of proof, and the presumption of innocence

◦ The burden of proof refers to the party that has the responsibility to prove the facts of the case. The burden of proof lies with the person or party who is bringing the case forward. In a criminal case, this is the prosecution.

◦ One of the justifications of this is that if the prosecution is accusing a person of having committed a crime, then the responsibility should be on the prosecution to establish facts to prove this

◦ In a few cases, this can be reversed (for example if the defendant is using the defence of self defence)

◦ The standard of proof refers to the degree or extent to which a case must be proven. It is the strength of evidence needed and in a criminal case, it is beyond reasonable doubt. That is, the doubt must be sensible and realistic.

◦ In other words, it is not good enough that the accused is “probably guilty”.

◦ The presumption of innocence is a major element of the rule of law. it stipulates that an accused person must be presumed innocent until proven guilty in a court of law, beyond reasonable doubt

◦ It originated as common law (judge made law through the courts) but is not also guaranteed in statute law – The Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act

◦ Guaranteed by the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic)

◦ By imposing high standard on prosecution to prove a case (beyond reasonable doubt) and imposing burden of proof on prosecution

◦ Through the system of bail – the release of an accused into society until the time of their hearing/trial. Conditions generally apply.

◦

The presumption of innocence

The presumption of innocence is a guarantee that an accused will be assumed to be not guilty until the charge has been proved beyond reasonable doubt.

The presumption of innocence is upheld by:

• imposing the burden of proof on the prosecution

• imposing a high standard on the prosecution to prove its case beyond reasonable doubt

• accused’s right to silence

• police must reasonably believe a person has committed a crime before they can arrest them

• for indictable offences, the prosecution must prove there is enough evidence to support a conviction before they can take a case to trial

• generally, a person’s prior convictions cannot be revealed until sentencing

• an offender has the right to appeal a wrongful conviction.

the rights of an accused, including the right to be tried without unreasonable delay, the right to silence, and the right to trial by jury

• Right to be tried without unreasonable delay: Definition: a person charged with a criminal offence is entitled without discrimination to a guarantee that they will be charged without unreasonable delay – that is, in a timely manner. Delays should only occur if they are considered reasonable.

• Source: Section 21 and 25 of the Human Rights Charter

• Going further: The Criminal Procedure Act 2009 states time limits for the commencement of trials, including murder within 12 months and sexual offences within 3 months

• “Without discrimination” means that no matter your prior history or personal attributes such as age, disability or gender, you should have this right.

A person charged with a criminal offence is entitled to be tried without unreasonable delay.

• This means that an accused is entitled to have his or her charges heard in a timely manner, and that delays should only occur if they are considered reasonable.

• • The reasonableness of any delay will depend on factors such as the complexity of the case and the legal issues involved.

• This right is ‘without discrimination’, regardless of prior history or personal characteristics.

• An accused child (person under 18) must be brought to trial as quickly as possible.

Right to Silence

The term ‘right to silence’ describes different types of protections given to an accused person to not have to say or do anything. These include:

• An accused has a right to refuse to answer any questions during the investigation of a crime.

• An accused does not have to give evidence in a criminal trial.

• No negative conclusions or inferences can be drawn because an accused exercised this right.

• Source: Common law and statute law

Right to trial by jury

• Definition: all those charged with an indictable commonwealth offence have the right to have their guilt determined by a jury of their peers. Thus it is a limited right as most crimes fall under state residual law.

• Source: section 80 Commonwealth Constitution

There is no right to a jury trial for summary offences.

• A criminal jury is made up of 12 jurors.

• The jury will hear the case and will need to reach a verdict on whether the accused is guilty beyond reasonable doubt.

Rights of Victims

the rights of victims, including the right to give evidence using alternative arrangements, the right to be informed about the proceedings, and the right to be informed of the likely release date of the offender

· the rights of victims, including the right to give evidence using alternative arrangements, the right to be informed about the proceedings, and the right to be informed of the likely release date of the offender

The rights of victims are recognised by a number of statutes in Victoria, including the Victims’ Charter Act 2006 (Vic), known as the Victims’ Charter.

The right to give evidence using alternative arrangements

• If a victim is a witness to a crime, they may have to give evidence in support of the prosecution’s case against the accused.

• The Criminal Procedure Act (2009) Vic allows for alternative arrangements (measures that can be put in place for witnesses to give evidence in a different way) in some cases.

• The purpose of alternative arrangements is to try to reduce the trauma, distress and intimidation that a witness may feel when giving evidence.

Cases in which alternative arrangements can be made

• The court can direct alternative arrangements to be made for any witness who gives evidence in criminal proceedings that relate to a charge for:

• a sexual offence

• a family violence offence

• an offence for obscene, indecent, threatening language or behaviour in public

• an offence for sexual exposure in a public place.

• If the witness is a complainant in a criminal proceeding that relates to a charge for a sexual offence or a family violence offence, the court must direct the use of closed-circuit television or other facilities unless certain circumstances apply.

Types of alternative arrangements

A range of alternative arrangements may be used while the victim is giving evidence, including:

• giving evidence from a place other than the courtroom by means of closed circuit television

• screens that remove the accused from the witness’s line of vision

• a support person may sit beside the witness

• only certain persons may be allowed in court

• legal practitioners may be required not to be formally dressed in robes, or required to be seated.

The right to be informed about the proceedings

• Victims are entitled to be informed at reasonable intervals about the progress of a criminal case (unless they do not want that information, or that information may jeopardise the investigation).

• This includes:

• being informed, at regular intervals, about the progress of an investigation into a criminal offence

• being provided clear, timely and consistent information about support services, possible compensation entitlements and the legal assistance available to persons adversely affected by crime

• once the prosecution has started, the prosecution must inform the victim of any charges laid, how they can find out details of the trial and the outcome of any proceeding (including sentencing), and the details of any appeals.

The right to be informed of the likely release date of the offender

• Victims of a criminal act of violence violent crimes can be included on the Victims’ Register.

• Once registered, victims receive information about an offender who has been imprisoned, including:

• notification of the release of the prisoner on parole at least 14 days before the release

• notification if the offender escapes from prison.

• The victim may also be able to make a submission if the imprisoned offender may be released on parole.

The principles of justice during a criminal case

Fairness means all people can participate in the justice system and its processes should be impartial and open.

• Fairness does not mean that all people who have been accused of a similar criminal offence will have the same type of hearing or, if found guilty, receive the same sentence.

Impartial processes

• Courts and personnel, including judges, magistrates and jury members, must be independent and impartial. They should not show bias towards or against either party, and the case must be decided based on facts and law, not on prejudices.

• There should be no apprehended bias (a situation in which a fair-minded lay observer might reasonably believe that the person hearing or deciding a case might not be impartial).

Open processes

• Open processes ensure the institutions and people (such as the police, courts and government departments and bodies) who administer justice can be scrutinised by the public and held accountable

• This is achieved by requiring hearings to be public, having court judgments available to the public, and allowing the community, media and victims to attend court hearings.

Participation

•People must be able to participate in the criminal justice system, including:

• An accused should have the opportunity to know the facts of the case and the case that is put against them.

•An accused should have the opportunity to prepare a defence and examine witnesses.

• An accused should be able to defend themselves personally or through legal assistance chosen by them.

• An accused person should have access to the free assistance of an interpreter if they cannot understand or speak English.

•An accused should be tried without unreasonable delay.

•Victims should be able to give evidence using alternative arrangements.

•Victims are able to give victim impact statements during sentencing.

• Other features of fairness:

•the right to silence

•the presumption of innocence.

Equality means all people engaging with the justice system and its processes should be treated in the same way. If the same treatment creates disparity or disadvantage, adequate measures should be implemented to allow everyone to engage with the justice system without disparity or disadvantage.

• Same treatment

• All people are treated the same and given the same levels of support, regardless of their personal differences or characteristics (such as race, religion, gender identity or age).

• This is referred to as ‘formal equality’.

• Different treatment

• if treating people in the same way could in fact cause disparity (a gap or difference between the way the two parties are treated) or disadvantage, then measures should be put in place to allow people to participate in the justice system without disparity or disadvantage.

• This is referred to as ‘substantive equality’.

• Measures that may need to be put in place to avoid disparity or disadvantage will depend on the circumstances of the case and of the parties, but may include:

• interpreters

• providing information in different ways (such as different languages or without legal jargon)

• changes to court processes

• using a different form of oath or affirmation

• breaks and adjournments.

Access means that all people should be able to engage with the justice system and its processes on an informed basis

• Engagement

• People need the means and ability to be able to use and participate in the justice system. This includes:

• physical access

• technological access

• financial access

• no delays.

• Informed basis

• People should be able to engage on an informed basis. This includes understanding their legal rights and processes involved in their case, and being able to obtain enough information to make reasoned decisions. This can be achieved by:

• education

• information

• legal and support services

• legal representation.

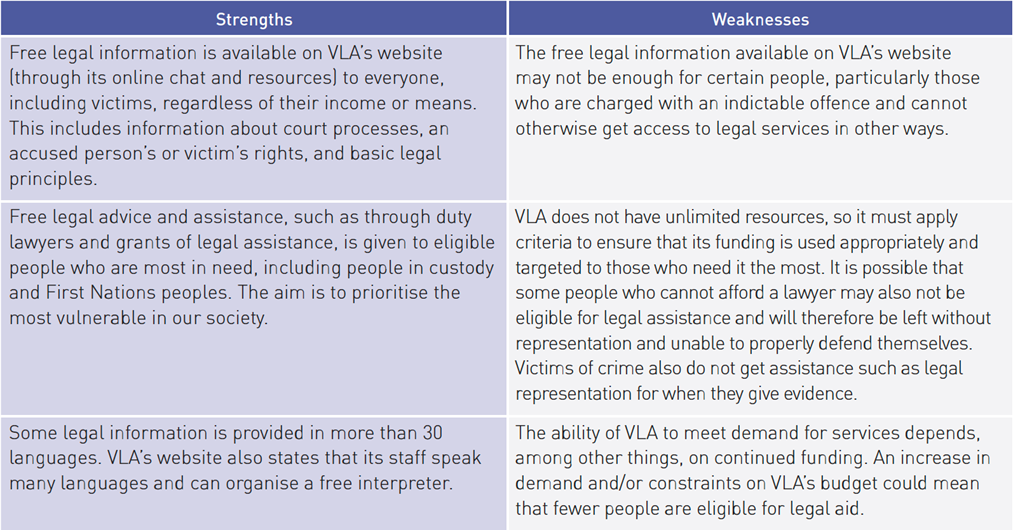

· the role of Victoria Legal Aid and Victorian community legal centres in assisting an accused and victims of crime

· Role of VLA

• Victoria Legal Aid (VLA) is a government agency that provides free legal information to the community, and legal advice and legal representation for people who cannot afford to pay for a lawyer.

• VLA prioritises people who need help the most and cannot get legal assistance any other way.

• VLA’s objectives are to:

•provide legal aid in the most effective, economic and efficient manner

• manage its resources to make legal aid available at a reasonable cost to the community and on an equitable basis throughout Victoria

•provide the community with improved access to justice and legal remedies

•pursue innovative means of providing legal aid to minimise the need for individual legal services in the community

• ensure the coordination of the provision of legal aid and legal assistance information so that it responds to the legal and related needs of the community.

Types of assistance for an accused

• free legal information (resources available to everyone online or by phone)

• free legal advice (in person, by video conference or over the phone)

• duty lawyer services (for those eligible, duty lawyers can assist people at court on a particular day by providing fact sheets about what happens in court, offering legal advice, or representing an accused in court on that day)

• grants of legal assistance (for those eligible, VLA may offer money to assist with paying for a lawyer).

Types of assistance for victims of crime

Victims are not parties in a criminal case, however VLA still assists with:

• navigating the criminal justice system

• getting advice or assistance with obtaining protection orders

• obtaining financial assistance or compensation for loss suffered as a result of crime

• identifying other supports that may be available to them (e.g. mental health support).

STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES OF THE VLA

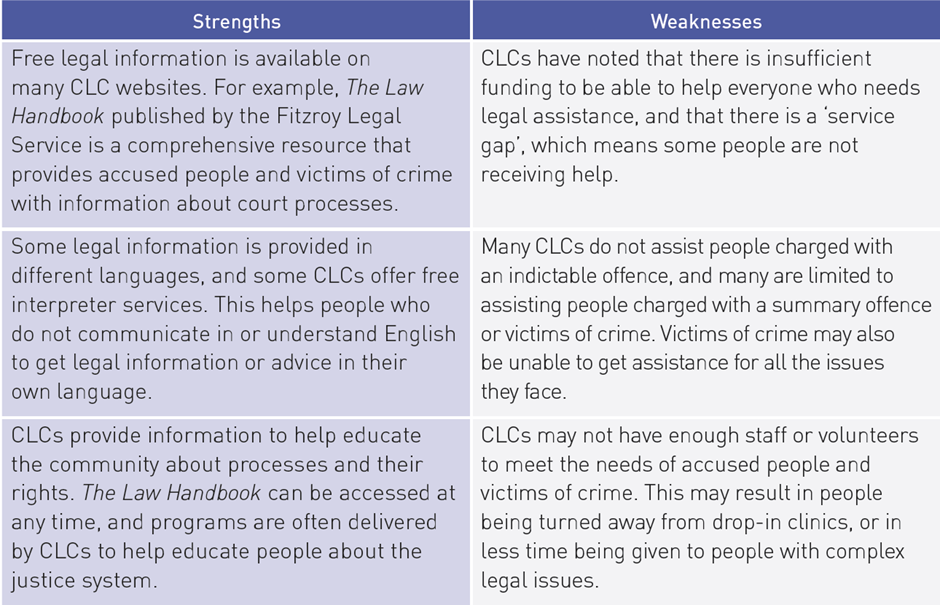

Role of CLCs

• CLCs are independent organisations that provide free legal services, including advice, information and representation, to people who may not be able to access legal services in any other way.

• CLCs also provide legal education to the community and advocate for changes to the justice system

• There are two types:

• Generalist CLCs provide broad legal services to people in a particular geographical area.

• Specialist CLCs focus on a particular group of people or area of law.

Types of assistance for accused people

• basic legal information (e.g. online resources and handbooks)

• legal advice and preliminary assistance in cases (e.g. helping write letters or complete forms)

• ongoing casework (e.g. legal representation)

• Types of assistance for victims of crime

• basic legal information (e.g. online resources and factsheets)

• legal advice and preliminary assistance in cases (e.g. help with completing forms)

• ongoing casework (e.g. applications for financial assistance or intervention orders).

Eligibility for CLCs

• Each CLC has its own eligibility criteria but may consider the following factors:

• the type of legal matter that the person needs help with

• whether other assistance is available, such as VLA

• whether the person has a good chance of success

• whether the CLC is available to assist.

STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES

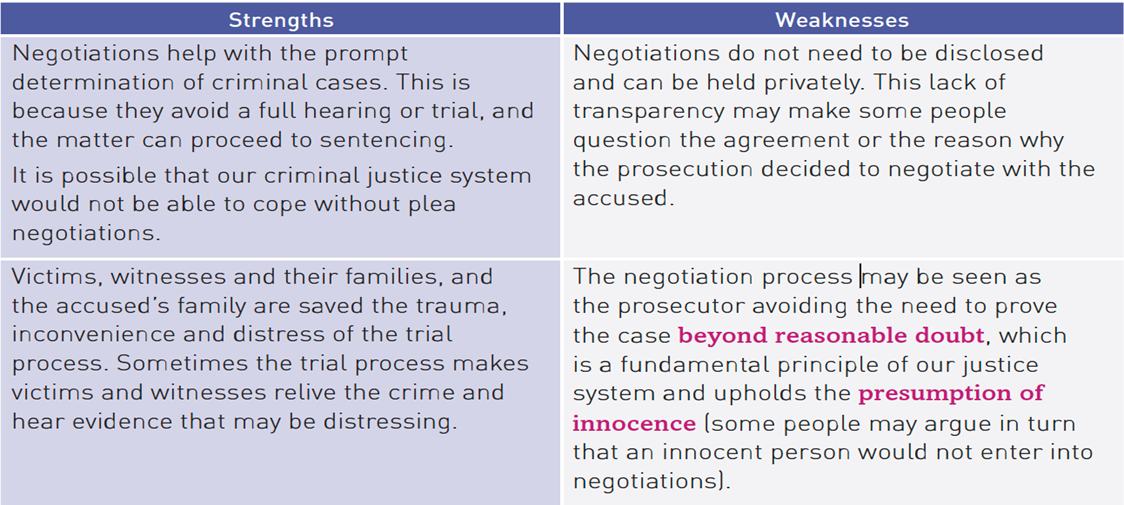

the purposes and appropriateness of plea negotiations

What are plea negotiations?

• pre-trial discussions between the prosecution and the accused, aimed at resolving the case by agreeing on an outcome to the criminal charges laid.

• can occur for both summary and indictable offences

• the agreement reached may be that:

o the accused pleads guilty to fewer charges

o the accused pleads guilty to a charge, but an agreement is reached about the facts on which the plea is based

o the accused pleads guilty to a lesser charge.

• Plea negotiations do not determine the sentence.

• Purposes of plea negotiations

• to ensure certainty of the outcome of a criminal case

• to save the court and prosecution’s costs, time, and resources by avoiding the need for a trial or hearing

• to achieve a prompt resolution to a criminal case without victims enduring the stress, trauma and inconvenience of a criminal trial

Appropriateness of plea negotiations

• A number of factors can be considered to determine whether plea negotiations are appropriate for a particular case:

• whether the accused is ready to cooperate in the investigation

• the strength of the evidence, including the strength of the prosecution’s case and of any defences

• whether the accused is ready and willing to plead guilty

• whether the accused is represented

• whether the witnesses are reluctant or unable to give evidence

• the possible adverse consequences of a full trial

• the time and expense involved in a trial

• the views of the victim.

STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES OF PLEA NEGOTIATIONS

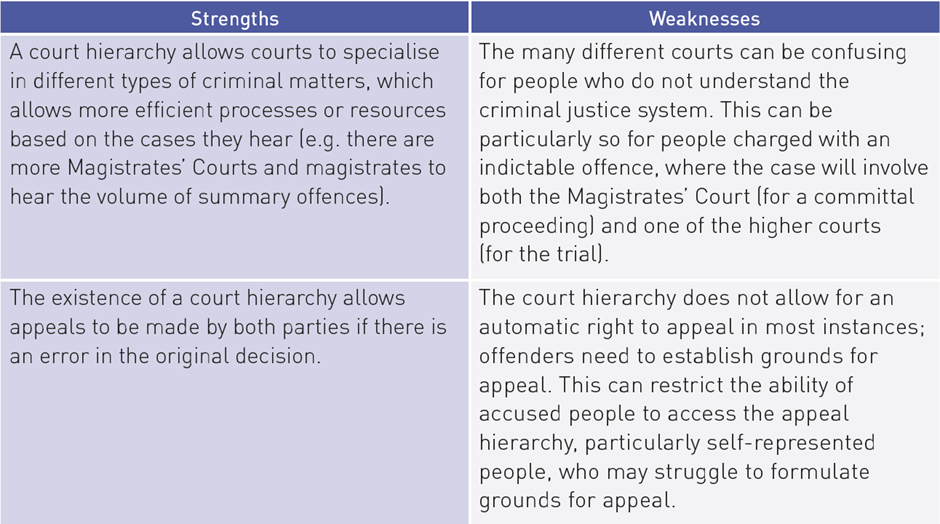

Reasons for a court hierarchy including specialisation and appeals:

Term | Definition |

Original jurisdiction: | Is the ability of a court to hear a case for the first time, or first instance |

Appellate jurisdiction: | Is the power of a court to hear a case on appeal for review |

Victorian Court Hierarchy: Criminal Jurisdictions

Reasons for a court hierarchy in determining criminal cases:

Specialisation

Within the hierarchy, courts develop their own areas of expertise.

• The Supreme Court (Court of Appeal) specialises in determining criminal appeals in indictable offences and has expertise in sentencing principles.

• The Supreme Court (Trial Division) hears the most serious indictable offences and has developed its own specialisation in the elements of those types of crime.

• The County Court has expertise in hearing particular types of indictable offences (such as drug offences, sexual offences and theft).

• The Magistrates’ Court is familiar with cases involving summary offences that need to be dealt with quickly and efficiently.

• Other courts such as the Children’s Court and Coroners Court deal with specialised cases.

Appeals

• If there are grounds for appeal, a party who is dissatisfied with a decision in a criminal case can take the matter to a higher court to challenge the decision.

• The system of appeals provides fairness and allows for any mistakes made in the original decision to be corrected.

• Grounds for appeal in a criminal case include:

• appealing on a question of law

• appealing a conviction (only by the offender)

• appealing because of the severity or leniency of a sanction imposed.

STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES OF COURT HIERARCHY