Neurological Theories

Brain Development

Introduction to Brain

- The brain is a fascinating organ composed of 80–100 billion neurons, each of which forms up to 30,000 connections throughout a lifetime.

- It consists of the cerebral cortex, the midbrain, and the cerebellum.

- Frontal, occipital, parietal, and temporal lobes make up the cerebral cortex's four major hemispheres.

- Each lobe is responsible for a specific function, and the cerebral cortex is covered with sulci and gyri.

- The frontal lobes are connected with planned behaviour, the detection of emotionally

- salient cues for the purpose of avoiding danger, and impulse control.

- The temporal lobes are important for memory, whereas the occipital and parietal lobes interpret visual and sensory information and place.

- The midbrain consists of the tectum, tegmentum, cerebral aqueduct, cerebral peduncles, and many nuclei, as well as the hippocampus, amygdala, and other structures.

Stages of Development

- Developmental neuroscience investigates the physiological changes that occur in the brain during childhood, adolescence, and old life.

- It is now understood that adolescence is a vital stage in the formation of a fully "adult" brain.

- Neurological maturation is not linear nor gradual; rather, it develops in surges.

- In terms of the amount of neuronal growth that occurs in the limbic, striatal, and prefrontal cortical regions, adolescence is second only to infancy.

- Throughout these stages of development, the brain undergoes arborisation, a process in which superfluous connections are gradually cut away.

- The links between executive processes in the frontal lobes, emotional processes in the amygdala (in the midbrain), and cognitive processing in the hippocampus are accountable for our decision-making abilities in emotionally charged situations.

- Prior to the ages of 23–25, the frontal lobes are among the last brain areas to reach full development.

- Neuronal plasticity is a crucial property of the brain that enables it to change and adapt in response to external stimuli.

- Utilizing structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and electroencephalogram (EEG) scans to track longitudinal changes in brain activity, this fast growth in the frontal lobes has been seen.

- Functionally, these changes are reflected in improved executive functioning, impulse control, and decision-making competence.

- In terms of forensic psychology, it is essential to explore the mapping of these neurodevelopmental alterations to the development of empathy and receptivity, theory of mind (the understanding that others have different experiences, ideas, and intentions from our own), and emotional behaviour.

- Children begin to develop theory of mind between the ages of three and four, and these abilities continue to mature and become more complex throughout childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood.

- Neuronal plasticity is the brain's capacity to change and adapt in response to external stimuli.

Neuronal Plasticity

Neuronal plasticity is a unique and adaptive property of the brain that permits the reorganisation of neuronal connections in response to internal or external stimuli.

Synaptic plasticity is essential for modifying brain circuits, which is crucial for our ability to rapidly acquire new behaviours and adapt to changing situations.

The brain is most malleable during youth, particularly between infancy and the ages of two to four, when fast development occurs.

Neurodevelopmental diseases, acquired brain damage, and other insults to brain morphology can have a negative impact on plasticity, substantially affecting an individual's capacity to learn, connect with their environment, and engage in meaningful social relationships.

Typically, an injury that occurs at a young age results in a recovery that is substantially less effective over time.

This has sparked a discussion as to whether young children are susceptible to injury, or whether earlier injury and subsequent brain alterations may allow for a more rapid recovery.

The most crucial information in this article is that language normally recovers well, whereas 'dorsal-stream functions' such as visuospatial function, attention, and later executive function appear to be less resilient to juvenile injury.

Injuries to the frontal lobe in children younger than 11 years old are the most severe because the neuro-plastic response of the brain is limited by the reductive effect of such lesions.

Emotional experiences in the environment alter brain development and, ultimately, how the brain processes information. In unfriendly, hazardous, or abusive environments, the brain must adapt so that the child can live.

Yet, emotion processing is also developmental, with each phase laying the groundwork for the next.

In forensic settings, the extent to which early unfavourable environmental events do result in hardwiring of intrinsic emotional states is sometimes contested and "blamed."

Normative Brain Development and Crime

Understanding the'melting pot' of vulnerability that leads to both adolescent-limited offenders and lifetime prolific offenders is essential for building rehabilitative judicial systems and lowering the number of victims of crime.

Teenagers are more likely to engage in risky behaviour, especially in emotional settings or in the presence of peers.

At a condition of emotional arousal, adolescents interpret information differently than adults, resulting in a greater propensity for aggression and conflict.

Compared to adults, teenagers' inhibitory control (the ability to control impulses and behavioural responses) is worse in stressful, emotional, and stimulating settings, and this impairment is exacerbated in the presence of peers.

When driving in the presence of peers, adolescents are more prone to make unsafe decisions than when executing the job alone.

- This is related to a phenomenon known as "temporal discounting," in which a delayed reward is valued less.

- This results in a lack of self-control and self-regulation, which increases susceptibility to substance abuse and conflict.

- This tendency to prefer tiny, quick gratifications (such as social acceptability, a drug "high," or peer status) without considering long-term implications is strongly associated with conduct problems and violent criminality.

Childhood Adversity

Impact of Childhood Adversity

- Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are a concept of 10 ACEs that can disrupt normal neurological development.

- These adverse childhood experiences include physical and sexual abuse, emotional and physical neglect, and family violence.

- Exposure to various environmental stressors during childhood influences the modulation and prioritisation of the development of some talents over others.

- Often, chaotic, aggressive, and abusive home settings cover numerous formative childhood years and several stages of development.

- As a developing brain is exposed to severe, terrifying surroundings, the fight or flight mechanism is heightened.

- This results in the conditioned selection of psychological and behavioural responses that are more severe in response to relatively non-threatening stimuli.

- Danger detection biases induced by violent childhood circumstances can also result in hypervigilance and a continual check of the surroundings for danger.

- As a result of important phases of development occurring in stressful, unpredictable, and frequently deadly circumstances, these damaging family environments lead to psychological dysregulation, resulting in chronically changed expectations and perceptions of the world.

Developmental Trauma

- Psychological dysregulation is accompanied by neural alterations and adaptive brain morphology in children growing up amid adversity.

- This can have a variety of pervasive impacts, including modest learning challenges and disabilities, difficulties retaining and processing instructions or rules in complex circumstances, and communication, speech, and language difficulties. In addition,

- Developmental Trauma frequently results in dissociation and detachment, which is a survival mechanism resulting from PTSD and other trauma-related disorders that allows the victim to not completely feel stressful, distressing, or emotional events.

- These children are at a high risk for having a clinically serious emotional disorder, although they display little insight of mood issues.

- Problems with integrative processing are characteristic of children's presentations and can lead to adult perplexity.

- These issues result in altered recruitment and activation between frontolimbic and temporoparietal processing regions, which are associated with insomnia and sleep difficulties.

- Due to a decoupling between the amygdala and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during encoding, threat detection biases might result in more severe responses to potentially hazardous events.

- Emotional and physical deprivation in childhood is also associated with a generalised reduction in cortical thickness, which has been connected to the onset of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Inadequate emotion regulation and maladaptive coping methods can lead to clinical symptoms of sadness and anxiety in adults who experienced childhood trauma.

- Ineffective integration of cognitive, emotional, and behavioural events can result in violent outbursts and involvement with the court system. In addition to these multiplicative vulnerability variables, substance abuse and neuro-disability are also potential contributors.

Maternal Factors

- Many maternal characteristics prevalent in unstable family contexts have a substantial impact on children's developmental outcomes.

- Prenatal maternal stress, particularly in the setting of emotional or physical domestic abuse, can have a major impact on a child's cognitive development, fine motor abilities, gross motor coordination, and adaptive social behaviours at the age of 30 months.

- In contrast, high levels of post-natal mother stress influence the social-emotional and temperamental development of infants at 30 months of age.

- Poor maternal mental health (such as prenatal or postnatal depression and post-traumatic stress disorder) is a risk factor for baby impairment and neurodevelopmental delay in sensorimotor and language development.

- Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) is a spectrum condition characterised by severe neurodevelopmental deficits that increase a child's susceptibility to antisocial behaviour, poor attention span, reduced executive function and memory, communication issues, and impaired behavioural control.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has revealed the extensive effects of alcohol on the developing foetal brain, as well as the fact that maternal alcohol consumption can result in overall reductions in brain volume, structural abnormalities in the cerebellum, hippocampus, and temporal lobes, and decreased volume in the frontal lobes.

- Compared to the general population, the prevalence of FASD is significantly higher among people in detention.

- There is also evidence that the criminal justice system is ill-equipped to handle the unique requirements of individuals with FASD, and that lack of appropriate staff training, awareness, and expertise, as well as inconsistent information sharing between institutions, are impediments to rehabilitation.

- Children diagnosed with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) at birth as a result of in utero exposure to medicines of dependence have a second maternal influence.

- As infants, these children are frequently brought to the special care baby unit with issues such as methadone withdrawal seizures.

- The toxicology of urine frequently reveals the presence of a combination of drugs, including morphine, benzodiazepines, methadone, and cocaine metabolites.

- During foetal development, exposure to medications of this type can result in severe brain damage (and sometimes death or miscarriage).

- These injuries can result in permanent impairment and learning incapacity. Relationships between drugs and foetal damage are complex, however, because the amount of exposure, type of drug/toxin, and trimester/s of gestation during which exposure occurred are likely to be relevant.

- Children are inevitably placed in adoption and care systems, which further complicates predictive relationships.

- Normally, NAS infants are distinguished by their appearance. As with FASD, it seems possible that difficulties can arise along a range of severity, and it is conceivable that sub-clinical newborns exposed to drugs in utero will have undetected abnormalities such as a "forgotten history."

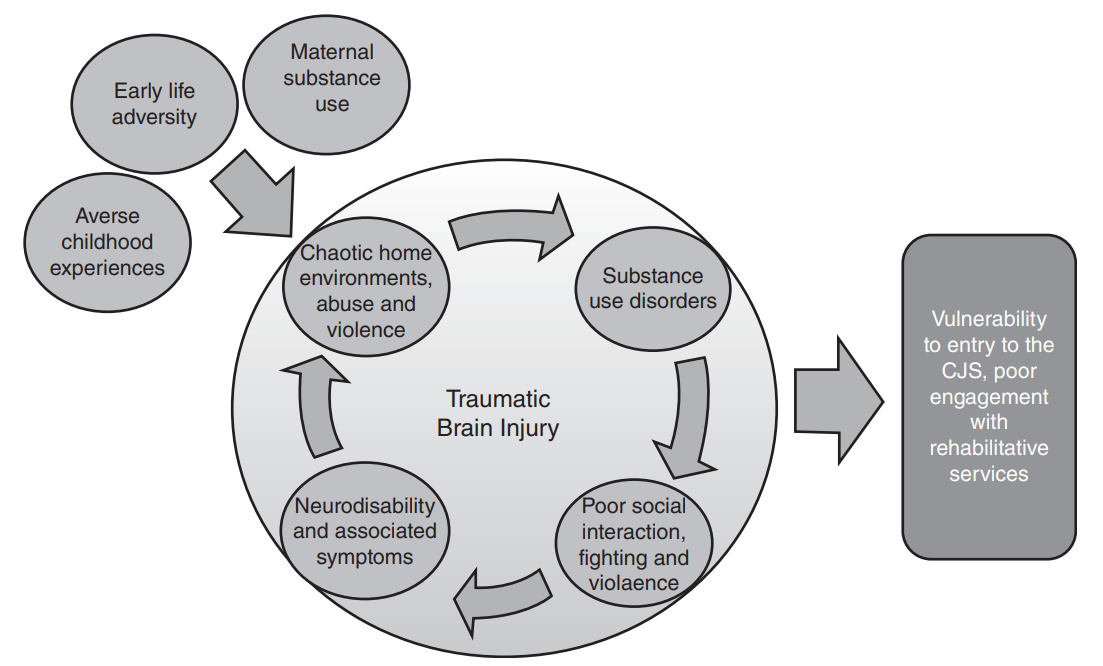

Neurodisability and Traumatic Brain Injury

Neurodisability

- Neurodisabilities are neurological defects that result in behavioural, cognitive, and social challenges.

- The 'social vulnerability theory' states that, throughout the transition to adolescence, children are unable to cope with increasing social pressures due to primary deficits in cognitive processing and emotional regulation.

- Neurodisability is more prevalent in criminal justice settings than in the general community, indicating a correlation between neurodisability and susceptibility to admission into the criminal justice system.

- Neurodisability can result in frustration, agitation, increased stress, diminished emotional regulation, and susceptibility to impulsive cognition and behaviour.

- It can have secondary effects that may not directly provoke crime or violence, such as social isolation and rejection.

- It has profound effects on neuromaturation and social development, which can be significantly aggravated by a traumatic brain injury.

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

Traumatic brain injury: A form of acquired neurodisability that can have catastrophic and lasting consequences.

It occurs when a blunt force or penetrating blow to the head causes brain tissue contusions, lesions, and bleeding.

Fights, assaults, falls, automobile accidents, and athletic accidents are common causes.

The most common cause of traumatic brain injury in children aged zero to four is falls, followed by abuse-related injuries such as shaking.

These are the most common causes of road accidents, conflicts, and sporting injuries among adolescents.

Teenage boys are more susceptible to TBI than girls, which is a major barrier to rehabilitation.

Poor socioeconomic position is associated with unstable and abusive home situations, which heighten TBI susceptibility.

TBI exacerbates neurodisability symptoms and can be the cause of communication difficulties, speech and language impairments, poor emotional regulation, and ADHD and autistic symptoms.

It is a multiplicative risk factor for poor social relations, impulsivity, irritability, and risky behaviour, especially when combined with Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Developmental Trauma.

Neuroinflammation

- Within minutes, a sterile immunological response is triggered by a traumatic brain injury.

- This neuroinflammation influences the stress response of the central nervous system, alters blood-brain barriers, and dysregulates hormones and neurotransmitters.

- Acutely, this immune response supports tissue repair and recovery, but when it persists, it can cause emotional and behavioural dysregulation and impair neuronal regeneration.

- High neuroinflammatory reactions following trauma or TBI can disrupt this process, resulting in more severe and devastating long-term repercussions.

Social Isolation and Deprivation of Liberty

Social Isolation

- Social deprivation is associated with mortality, morbidity, and a plethora of other mental and physical health problems.

- Many cortical and sub-cortical systems, including the amygdala, ventral striatum, and orbito-frontal cortex, are affected by social isolation.

- Notwithstanding the negative impacts of long-term social isolation, it is frequently employed as a form of punishment for children and adolescents, including internal exclusion at school, external exclusion, and expulsion throughout primary and secondary education.

- Recent research has emphasised the "classroom to courtroom" dilemma, in which children excluded or expelled from school are considerably more likely to become juvenile offenders in the criminal justice system.

- Isolation and exclusion at school disrupt and affect normal peer connections, resulting in fewer friendships and incorporation into antisocial peer networks.

Importance of Play

- Play is necessary for cerebral development, which is hindered by social isolation, exclusion, and lack of freedom.

- It has been discovered that play develops executive function skills, planning, resilience, social ability, relationships, and self-regulatory abilities, which are crucial for executive function and attention.

Deprivation of Liberty

- The United Nations' general remark no. 24 (2019) on children's rights recognises the significance of rehabilitative, as opposed to punishing, environments in the criminal justice system to protect the normal neurological development of children.

- It describes the increased likelihood of neurodisabled children coming into contact with the criminal justice system, as well as the risk of criminalising neurodisability and creating a "revolving door" situation in which the most vulnerable are at risk of reoffending without adequate rehabilitative support.